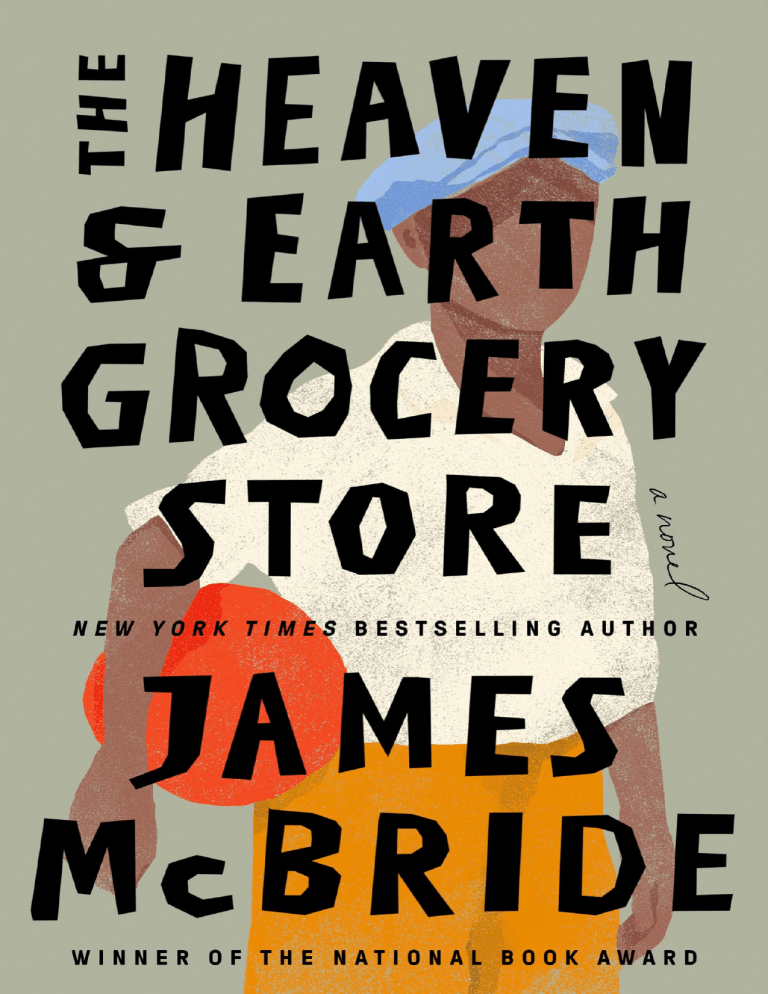

The Heaven Earth Grocery Store A Novel (James McBride) (Z-Library)

advertisement