contrasting-languages-to-predict-difficulties-and-improve-teaching-an-analysis-of-contrastive-linguistics-and-its-application-to-english-language-instruction-for-vietnamese-learners compress

advertisement

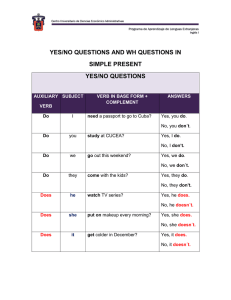

I – Generalities of Contrastive Linguistics 1. Definition of Contrastive Linguistics Contrastive Linguistics, as known as Contrastive Analysis (CA) has been a topic of interest for a multitude of researchers in the linguistic fields. In Carl James’s ‘Contrastive Analysis’ (1980, p.3), CA is provisionally defined as “a linguistic enterprise aimed at producing inverted (i.e. contrastive, not comparative) two valued typologies (a CA is always concerned with a pair of language), and founded on the assumption that languages can be compared”. A linguistic enterprise can be classified into various types and there are certain dimensions which such classification can be based on. According to James (1980), there is no clear distinction amongst the classificatory dimensions of CA as a linguistic enterprise. Regarding the particularist and the generalist approaches to linguistics, CA appears to stand somewhere between the two extremes, which means that CA not only treats individual languages but also the general phenomenon of human language. Accordingly, CA both studies the unique and distinctive features of the particular languages and the comparability of languages. However, it should be noted that classification is not the aim of CA but the differences, rather than the similarities between languages should be the focus of study for contrastive linguists. Concerning the third dimension of a linguistic enterprise, James concludes that CA does not give enough commitment to the study of static linguistic phenomena to be classified as synchrony. Instead, as part of Interlanguage Study, CA should be viewed as diachronic in orientation, in the sense that CA concerns with change within the human individual such as the study of second language or foreign language learning when a monolingual becomes a bilingual. Therefore, CA bears resemblance with the study of bilingualism, which by definition is the study on individual or societal possession of two languages, in certain aspects. 1 Another dimension of a linguistic enterprise that is worth mentioning concerns the distinction between ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ linguistics. James (1980) holds the view that CA can be in the form of both ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ linguistics. To elaborate, 'pure' linguists seek for the universals of language and confirm their findings by the deep analysis of single languages. During such process, the researchers actually engage in CA. However, James believes that CA is only ‘a peripheral enterprise’ of the ‘pure’ while it is the central component of ‘applied’ linguistics. Such viewpoint of CA as a crucial part of applied linguistics seems to be well supported by the contrastive hypothesis by Robert Lado (1957) which asserts that contrasting two languages would assist in predicting and describing the difficulties in learning a second language. This application of CA in second language acquisition has its theoretical assumption that CA is founded on the transfer theory. Lado (1957) points out that L2 learners tend to transfer the knowledge about the native language to the target one. Such claim about this psychological basis of CA can likewise be found in Al-khresheh’s research (2016), in which transfer is defined as the inevitable influence of the learner’s mother tongue on the learning of the second language. Transfer should be deemed a significant part in language learning as it is used as a learning strategy. Learners begin their second language learning by transferring sounds, meanings, then word order and structural rules from their mother tongue to the target language. Accordingly, should there be any differences between the two languages, the transfer process will bring about potential errors. By recognizing such differences between two languages, CA helps not only to explore errors but also serve as a method for expecting them. Fisiak (1990), in attempt to distinguish theoretical and applied contrastive analysis research, mentions the application of CA research in analyzing language for bilingual education, translation and any practical specific purposes. Concerning the potentials of CA in not only language teaching, but also many other linguistic fields, a procedure of five steps for CA has been proposed by Al-Khresheh 2 (2016), which includes selection - description - comparison - prediction – verification. First is the selection when two languages are taken for comparison. It should be noted that it is difficult to compare every aspect of language so the analysis should be limited to certain categories, which means that in the very first step of analysis, the specific unit of language must be selected. Second is the description of the selected unit of language within the same theory. Third, after describing the language unit, it is essential to compare the structures with each other to see the similarities and differences and the main focus should be on the differences. Fourth, prediction of the learners’ difficulty in second language learning is made through the contrast. Finally, the last step of CA is ‘verification’ in which the researcher should confirm whether the predictions given in the previous step are true or not. So far, CA has been mentioned as a linguistic enterprise which seeks to study and explain the similarities and differences between two languages. Based on the assumption of the transfer theory, CA is carried out with a view to applying knowledge about the differences of the two languages to make implications for practical specific purposes, one of which is language learning. 2. Contrastive Linguistics versus Comparative Linguistics Contrastive Linguistics and Comparative Linguistics are two fields in linguistic study and there should be a clear distinction between these lest mistakes occur when referring to such terms. According to Gómez-González and Doval-Suárez (2005) the term Comparative Linguistics is used almost exclusively to refer to the diachronic study of genetically related languages. In other words, Comparative Linguistics is to reconstruct form of the parent language and helps classify languages into family. According to Krzeszowski (1990), there are various approaches to linguistic comparisons. The Historical Comparative Linguistics in the 19th century helped identify the common features of 3 large groups of languages, thereby classifying them together into families. Another direction for Comparative Linguistics is the Typological Linguistics, which compares and groups both genetically related and unrelated languages together based on the shared features with a view to identifying language universals. In contrast to Historical Comparative Linguistics, (CA) is neither concerned with historical developments nor with the problem of describing genetic relationships. CA is synchronic in the sense that it studies languages of the same period without paying much attention to their histories or language families. The subjects of comparison in CA is not restricted to the parent language as those of Comparative Linguistics. Additionally, CA is typically concerned with a comparison of corresponding subsystems in only two languages, with the main focus on the differences rather than the likeness between the pair of languages. To recapitulate, Contrastive Linguistics does not refer to the same field of study as Comparative Linguistics. Their differences lie in not only the diachronic and synchronic nature, but also the aims of study. While the former seeks to identify the differences amongst two languages, thereby anticipating potential errors in language learning; the latter aims at classifying languages into language families based on their shared features, as well as finding the universals of languages. II – Illustration of Pedagogical Exploitation of Contrastive Analysis The significance of CA in language teaching has been pointed out by various researchers. Specifically, Lado (1957) believes that the knowledge about two languages can be applied by teachers in various pedagogical processes such as diagnosing difficulties and preparing materials for students. James (1980) likewise mentions the application of CA in predicting and diagnosing second language errors committed by leaners and in designing testing instruments. According to Lee (1968), 4 the use of CA in the context of language teaching is based on five assumptions that: (1) the prime cause of difficulty and error in foreign language learning is interference from the learners’ native language; (2) these difficulties are due chiefly to the differences between the two languages; (3) the greater these differences, the more acute the learning problem will be; (4) a comparison between the two languages will predict difficulty and error; (5) this comparison should determine what is to be taught. Based on such assumptions, the following part of this paper will attempt to provide illustrations of the application of CA in teaching English as a foreign language to Vietnamese learners. Apparently, the Vietnamese and English language will be analyzed and contrasted to determine mostly the differences between them; hence prediction of errors and explanation of error occurrence. 1. Verb form in English and Vietnamese from a contrastive perspective It can be observed that in many English classes, Vietnamese learners often have certain difficulties in providing the correct form of the verb (in agreement with the subject and tense). It is so common a phenomenon that it is worth the effort to investigate the possible cause of the occurrence of errors; thereby proposing measures to help leaners overcome these difficulties. From my own teaching experience in actual classrooms, students who are new to English learning often get confused when they are introduced different forms of the verb. Even when they have been able to do the grammar-based exercises on specific forms, i.e. exercises on Present Simple verb form, when it comes to using knowledge of grammar to produce a piece of writing, many of them fail to provide the correct verb form. Another case is a 9 th grader who I have been teaching. She made a comment about learning English that the subject-verb agreement is so troublesome, and “How come English is not the same as Vietnamese of which the verbs have only one form for every tense?” Obviously she has had a point in recognizing the difference between English and Vietnamese. That triggers my interest 5 in seeking plausible explanation for the difference to help not only this 9 graders, but also other students who encounter the same problems with English. To find the answer to the question of that 9 th grader is to examine some morphological and grammatical features of both Vietnamese and English language. Morphology focus on the study of morphemes and their different form, and the way they combine in word formation. Morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit in a language, which cannot be divided without altering or destroying its meaning. Accordingly, languages can be classified into inflectional language such as English and isolating language such as Vietnamese. According to Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, & Svartivik (1989), English is an inflected language that uses morphological morphemes to indicate tense in verb and number in noun. For example, the word discloses consists of a root (free) morpheme close and two bound (inflectional) morphemes, as known as affixes, dis- and -s. An English word can be comprised by one or multiple morphemes. In contrast, Vietnamese is an isolating language in that the grammar primarily consists of word order and the use of function words rather than bound morphemes. Therefore, the typical feature of Vietnamese is not inflectional as that of English; and word order is of great importance. Vietnamese belongs to the type of language that each word contains a single morpheme and there is absolutely no change in the word form by adding inflectional morpheme to the root as in English. Understanding of the contrasting language types between Vietnamese and English language allows probable explanation of initial obstacles faced by Vietnamese learners. In particular, when learning English words, learners may suffer less difficulties in learning new word in isolation than in a phrase or a sentence. Due to various grammatical relation amongst words, the words learners encounter in a text may change because of affixation. Speaking Vietnamese as the mother tongue does not necessitate the knowledge about inflections; therefore Vietnamese learners are not accustomed to the change in words 6 by adding either suffixes or prefixes, which causes various difficulties in English learning. Specifically, concerning the verb grammatical categories in the two languages, the distinctive feature of English is the change in verb form while Vietnamese verb is unchanging. The table below give examples of the verb in each category in both languages: Verb Category Types Examples of English Example of Vietnamese Person 1st, 2nd, 3rd I play; You play; He plays. Tôi chơi; Bạn chơi; Anh ta chơi. Number Singular Plural He plays; They play. Anh ta chơi; Họ chơi. Tense Present, Past, Future He plays; He played; He will play. Anh ta chơi; Anh ta đã chơi; Anh ta sẽ chơi. Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous Indicative, Imperative, Subjunctive He plays; He is playing; He has played; He has been playing. He always plays games. Don’t play games! I wish he didn’t play games. Anh ta chơi; Anh ta đang chơi; Anh ta đã chơi được nửa tiếng; Anh ta đã và đang chơi. Anh ta luôn chơi trò chơi. Đừng chơi trò chơi. Tôi ước anh không chơi. Active Passive They often play soccer; Soccer is often played. Họ thường chơi bóng đá. Bóng đá thường được chơi. Aspect Mood Voice The verb play in its infinitive form has its equivalent chơi in Vietnamese. What is not equivalent in the various examples containing such verbs is the multiple forms of play to indicate each grammatical relation in terms of person, number, tense, aspect, mood and voice. Meanwhile, the verb chơi in Vietnamese examples remains unchanged. Instead of changing the form and adding inflections (i.e. the morpheme – s/–es added to the infinitive to indicate 3rd person and singularity in the Present Simple; the morpheme –ed as indicator of Past Simple), Vietnamese marks these features by separated words, governed by the rule of word order to keep the meaning clear. For 7 example, to mark the past tense of the action, đã is used before the verb chơi, or the present continuous tense is marked by the use of đang before the verb. Vietnamese learners have been very familiar with this stable verb pattern; therefore providing the correct form of verb poses quite a big challenge to them, especially when it comes to verb forms requiring the knowledge of multiple categories. A clear evidence is the verb form the Present Simple tense. First, leaners have to get accustomed to the person category, then the number to decide whether the verb should stay infinitive or be added the suffix –s/–es. The Present Simple is conventionally the first English verb tense to be introduced to learners, and it is observable that leaners often get confused when being exposed to various aspects of the verb. The influence of Vietnamese verb pattern can also be observed in actual language classes of mine in which the writing skill is taught. The elementary learners frequently forget to add suffix to the verbs and ignore the subject-verb agreement. As a result, although they can communicate their message through their piece of writing, the grammatical accuracy is not guaranteed. Therefore, in teaching English verb form, it is highly recommended that the aforementioned differences be acknowledged by learners when they are newly exposed to English. Teachers should introduce the verb tense with extreme patience to elementary leaners, especially those with less linguistic intelligence, so that they have sufficient time to get accustomed to new aspects of languages. Since the grammatical relation of subject-verb in English is rather complicated with various categories affecting the choice of form, it is detrimental if knowledge of grammar is provided in abundance without detailed explanation and adequate practice. Novice teachers are likely to ignore the differences between two languages, thereby bombarding learners with new terms that they cannot absorb immediately. To tackle the differences, it is of paramount importance that learners have sufficient practice to familiarize themselves with new aspects of the language, hence building a firm foundation for further upgrade of language proficiency. 8 2. Word order in English and Vietnamese from a contrastive perspective In teaching the structure of English sentence, the teacher have to provide the form of verb in positive, negative and interrogative sentence. At sentence level, there are many more language issues that students have to take into consideration at the same time to be grammatically correct besides the subject-verb agreement. While there are certain similarities in Vietnamese and English positive sentence structure, many grammatical characteristics are not shared between the two languages, causing potential obstacles for students in acquiring their target language. Giang Tang (2007) summarizes some grammatical features of Vietnamese and English to better illustrate their similarities and differences, the three first comparisons are mentioned as follows. VIETNAMESE ENGLISH Word order SVO, OSV less common N + Adj SVO Adj + N Negation không + V Tôi không ăn. S + auxV + not + V… She could not open the door. Content questions Question word occupies answer-slot Cô ăn tối ở đâu? Tôi ăn ở nhà. Ai muốn ăn? Cô ấy muốn ăn. Question word + auxV + S + V… Where will you eat dinner? I will eat at home. Who wants to eat? She wants to eat. According to Giang Tang (2017), Vietnamese and English share the general word order of subject-verb-object. For example, the English declarative sentence I clean the room has it Vietnamese equivalent Tôi dọn phòng with exactly the same pattern of the subject (I – tôi), verb (clean - dọn), object (phòng – the room). As mentioned before, such similarity is beneficial for the transferring of knowledge of the native language to that of the target language. Therefore, elementary English learners can distinguish sentence components when given a simple English sentence and make similar ones by roughly combining the single noun and verbs they have learned. 9 However, this transferring process may cause problems when learners try to use noun phrases without acknowledging the crucial difference in the word order within such phrases between the two languages. In particular, English noun phrases can consist of one or several adjectives preceding the head noun while in Vietnamese adjectives follow the nouns they describe. Due to that contrast word order, a learner may make such mistake as I have an apple green when he tries to transfer from the Vietnamese sentence Tôi có một quả táo xanh. Not only in producing language will learners face problems, but when it comes to reading comprehension, learners may be presented with difficulties because their understanding mechanisms have to switch between two contrast word orders. To be able to speed up reading means the switching process have to occur quickly and efficiently, which requires much effort from the learners to familiarize themselves with a new pattern of word. While leaners may transfer a simple declarative sentence from Vietnamese to English with correct word order, they may make mistakes in making negative sentence. Forming a Vietnamese negative sentence from a declarative one seems to pose no difficulty because there is no change of the verb form. Negation may be indicated using không (no) before the verb as in Tôi không chơi (I – no – eat). When the linking verb là is used, the phrase không phải (no-correct) should be used as in Tôi không phải là cầu thủ. Meanwhile, negation in English may be indicated using “not” in between the auxiliary verb and the main verb as in She does not work. What causes the potential errors for Vietnamese speakers learning negative sentence in English is the presence of the new concept auxiliary verb, which is added before the main verb according to the tense and subject of the sentence. Auxiliary verbs complicate the learning by not only interrupting the familiar sentence structure, but also by their various forms. There is one observation situations in which the sixth graders are confused by the verb have. After learning the Present Perfect tense with have functioning in the sentence as an auxiliary verb i.e. I have played the piano, the students made such sentences as I 10 haven’t to wake up early. Obviously, have in the second sentence is the main verb in Present simple form and to make a correct negative sentence, an auxiliary should be added. The students mistake the function of have as auxiliary verb and main verb. Additionally, one striking difference between English and Vietnamese in terms of word order lies in the content questions. In English, there is a movement of the auxiliary verb compared to the declarative and negative sentence. For example, the declarative sentence She will go out can be restated as a question When will she go out? in which the auxiliary verb will and the subject she have changed places. This transposition does not occur in Vietnamese, in which content questions are formed using the same SVO structure of a declarative sentence with the placement of a question word in the slot that would contain the answer. For example, the declarative sentence Cô ấy sẽ ra ngoài can be restated as a question Cô ấy ra ngoài khi nào? It is apparent that there is no change in the word order of the question compared to the statement and the formation of question is only the addition of the question word in either the beginning or end of the SVO structure as in (Cô ấy ra ngoài khi nào? – Khi nào cô ấy ra ngoài). In brief comparison, The differences between Vietnamese and English question structure lie in: (1) the presence of the auxiliary verb causing changes in verb form, compared to the declarative sentence; (2) the order of the auxiliary verb; (3) order of the question word. In making English questions, learners have to take into careful consideration various factors to produce grammatically correct sentences. Such distinctive features of English causes difficulties for learners when it comes to both composing questions and answering questions. The former issue refers to the fact that it may be challenging for some learners to decide the correct auxiliary verb to be used, or which should be repositioned. In Vietnamese, the slot that contain the answer is replaced by an appropriate question word with the other parts of the sentence remaining in place. However, in English, the place of the slot containing the answer 11 decides the form of structure of the sentence. The presence of auxiliary verb is often taught and emphasized by teachers when teaching questions, i.e. Who does this bag belong to?, but there is a type of English question that requires no auxiliary verb, which is when the slot containing the answer is in the subject position of the sentence, as in Whose bag is this? Another problem is in answering questions. For example, the question Who does this bag belong to? can be likely answered This bag belong to him. with the verb given in the correct form. This error occurs also due to the difference in the verb form between Vietnamese and English, as mentioned earlier. Therefore, teaching the question form is rather a complicated matter. It is difficult for learners to remember the structure of the sentence especially when they tries to transfer it from Vietnamese structure. As the key difference between the two languages lies in the auxiliary verb, it is recommended that its presence be highlighted to familiarize learners with the new concept. Supposed that they bear in mind the necessity for an auxiliary verb and the distinction between it and the main verb, they will be less likely to tolerate the absence of the auxiliary in English negative and interrogative sentences. 3. Conclusion Given the aforementioned comparison between certain linguistic features of Vietnamese and English, some conclusion can be made about the potential interaction between Vietnamese and English. It is predicted that Vietnamese native speaker when making English sentences will likely to: first, omit words ending for tense and agreement with the subject; second, omit auxiliary verbs, third, have difficulty with word order in questions. The first problem results from the nature of the two languages as inflectional (English) and isolating (Vietnamese). The unchanged form of Vietnamese verbs regardless of tense and subject is contradict with that of English words which require many changes, both regular and irregular forms in accordance 12 with time, person, voice, and other grammatical categories. The combination of various factors in deciding the correct verb tense would beset learners with many difficulties. Additionally, the presence of auxiliary verb in English negative and interrogative sentences also pose problems for Vietnamese native speakers. The auxiliary verb, as English verb, changes its form according to the tense and subject and also change the sentence structure in the question form. If those problem is not addressed properly from the very beginning of the learning process, it would cause detrimental consequences and demotivate learners from acquiring the target knowledge. It is highly recommended that an enormous amount of time be allotted to the introduction of new language elements to students in comparison with their native language. It is believed by Lee (1968) that the pedagogical value of contrastive analysis is undeniable; however, it should not be overemphasized in language teaching. It is suggested that errors be predicted through classroom observation by experienced teachers because CA may not disclose all errors that students have. CA should be utilized as a source of reference from which the teacher designs teaching materials and classroom activities, as well as testing instruments to facilitate the language acquisition process. Henceforth, the teacher bases on students’ actual performance in class to continue modifying the teaching procedure. 13 REFERENCES Al-khresheh, M. H. (2016). A review study of contrastive analysis theory. Journal of Advances in Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(6), 330–338. Fisiak, J. (1990). On the present status of meta-theoretical and theoretical issues in contrastive linguistics. In Fisiak, J. (ed.), 3-22. Gómez-González, M. de los A. & Doval-Suárez, S.M. (2005). On contrastive linguistics: Trends, challenges and problems. In C.S. Butler, M. de los A. GómezGonzález & S.M. Doval-Suárez (Eds.), The Dynamics of Language Use. Functional and Contrastive Perspectives (pp. 19-46). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. James, C. (1980). Contrastive Analysis. Longman. Krzeszowski, T.P. (1990). Contrasting Languages. The Scope of Contrastive Linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Lado, R. (1957). Linguistics across cultures. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of MichiganPress. Lee, W. R. (1968). Thoughts on Contrastive Linguistics in the Context of Language Teaching. Monograph Series on Languages and Linguistics, 185-194. Quirk, R. Greenbaum, S, Svartvik, J. (1989). A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman Inc. Tang, G. (2007). Cross-Linguistic Analysis of Vietnamese and English with Implications for Vietnamese Language Acquisition and Maintenance in the United States. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement, 2(1). 14