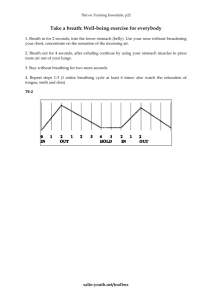

The Healing Power of the Breath Simple Techniques to Reduce Stress and Anxiety, Enhance Concentration, and Balance Your... -Shambhala

advertisement