end-of-life-a-guide-for-humanists-and-non-religious-people-in-bc5x8

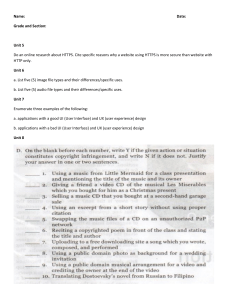

advertisement