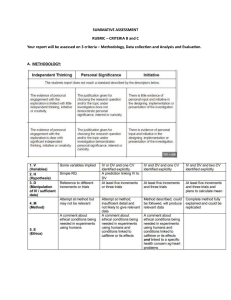

Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Module Code: RMH4008-N-JB2-2018 Module Title: Evidence Based Practice Module Leader: Barbara Neil Title: Does the delivery method of CBT impact on the effectiveness in reducing symptoms for adults with a primary diagnosis of depression when compared with treatment as usual? Name: Davy De Geeter Student No: V8386530 Date of Submission: 06/11/2020 Word Count: 4000 1 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Table of Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction and Background ................................................................................................................. 3 Evidence Based Practice ......................................................................................................................... 5 Ask a question ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Accessing the information ...................................................................................................................... 7 Appraise the article found .................................................................................................................... 10 Internal Validity................................................................................................................................. 11 External validity................................................................................................................................. 13 Discussion of results.......................................................................................................................... 14 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................ 15 Apply the information ........................................................................................................................... 16 Audit ...................................................................................................................................................... 17 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 18 References ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Appendix ............................................................................................................................................... 23 Appendix A: Search results for each database ................................................................................. 23 Appendix B: Chosen research paper ( López-López, et al., 2019)..................................................... 26 Appendix C: CASP Systematic Review Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2020) ...... 37 Appendix D: Force Field Analysis ...................................................................................................... 40 Appendix E: Change plan .................................................................................................................. 40 2 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Executive summary NICE guidelines (2009) show us that depression affects more than 300 million people globally. It is considered a leading cause for disability as well as one of the most common psychiatric conditions, as concluded by data from the World Health Organisation (2018). Studies such as those conducted by Public Health England have shown that the prevalence of diagnosed depression in the North East is 10% with lower rates in Newcastle, Hartlepool and Middlesbrough. It is suspected that these lower rates are due to a higher rate of undiagnosed depression. Currently there is wide amount of research available that shows that therapeutic intervention is effective for depression, especially cognitive behavioral therapy (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009). This therapy was founded and based upon the work of Beck (1974) who suggest that the maintenance and root of depression lies with the cognitive triad, more specifically a negative view of oneself, the world and the future. This report aims to reach a conclusion on the question: Does the delivery method of CBT impact on the effectiveness in reducing symptoms for adults with a primary diagnosis of depression when compared with treatment as usual? Following a structured search, a systemic review by López-López et al. (2019) was chosen as the most effective way of answering this question. The study concluded that strong evidence was found that CBT interventions yielded a larger decrease in symptom scores in the short term when compared with treatment as usual. There were however some issues with both the internal and external validity of the study as well as it being unclear which combination of content components and delivery formats are effective. This suggests that results need to be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, suggestions can be made how to effectively implement these suggestions into local therapeutic practice. Introduction and Background Depression is an enduring low mood that can affect your everyday life ranging from mild symptoms that have an effect on your motivation to very severe impairment linked with suicidality (Mind, 2019). When considering the DSM 5 diagnosis criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), we see further support for the psychological impact of depression as well as adding the potential for physical symptoms like fatigue, a decrease or increase in appetite and a slowing down of thoughts 3 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 and movements. Depression can take on a relapsing and remitting course and thus be episodic. This is further supported by the findings of Judd (1997) which estimate that the risk of repeated episodes is higher than 80% and most clients will on average experience 4 major depressive episodes in their lifetime. It is critical to stress that this is a factor in why mood disorders take a particularly important place in the risk factors for suicide. Findings by Harris and Barraclough (1997) show that mortality rates are on average 60% higher and their life expectancy 10 years shorter. They conclude that suicide is the main cause of this higher mortality rate and estimate the risk of suicide 20 times higher in people who suffer from severe depression. It is therefore imperative that good quality treatment is available for this group. The treatment of depression for clients diagnosed with the condition is happening for the most part within the primary care setting. 80% of this group is either receiving care from a GP or their primary care mental health team (Louch, 2009). It was however recognized by Lovell and Richards (2000) that only a minority was receiving the treatment they require. Further studies even go as far to suggest that 56% of clients with major depression receive no treatment at all ( (Fernández, et al., 2007) (Kohn, et al., 2004)). They conclude that barriers to care and ability to reach out for help are among those factors that contribute to this. It is for this reason that the stepped care model was brought into existence. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies stepped care model (The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2020) and the services which have been set up in accordance with this model provide evidence based therapy for people mainly diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorders. The model works according to the principle that the least intrusive intervention should be offered for their needs first. The appropriate choice of the level of treatment is informed by specific NICE guidelines for each disorder (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020). In the case of depression NICE (2009) recommends Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). CBT has been established as a effective treatment for a wide variety of mental health disorders including depression (Whitfield & Williams, 2003). In a study conducted by Cuijpers et al. (2013) the enduring effect of CBT after termination of the acute treatment was confirmed and found as effective as continuation of pharmacotherapy in the 18 month follow up. Such studies, however, fail to address that good quality research such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with long follow ups beyond the two years are rare as is shown in research by Steinert et al. (2014). Their findings 4 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 continue by suggesting that relapse rates after 4 years are considerably high and thus further developments need to be made to enhance relapse prevention strategies. CBT interventions are complex and our chosen systematic review and meta-analysis for this report delves further in the effectiveness of both the components and different delivery methods that are utilized in current practice ( López-López, et al., 2019). Evidence Based Practice Evidence Based Practice (EBP) aims to close the distance between actual clinical care and best practice by applying the evidence gained from robust research studies and adding in the therapist’s experience and clinical decision-making skills as well as the client’s own preferences and ideals (Fineout-Overholt, et al., 2005). A more detailed definition is given by Sackett et al. (1996) who describes EBP as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence, based on systematic review of all available evidence- including patient reported, clinician observed and research derived evidence- in making and carrying out decisions about the care of individual patients”. To emphasize the importance of integrating these different aspects Hoffman et al. (2010) stress the importance of structuring this approach rather than it remaining a vague concept. This can be achieved by following the five steps set out in Strauss et al. (2019): 1) Convert your information needs into an answerable clinical question 2) Find the best evidence to answer your clinical question 3) Critically appraise the evidence for its validity, impact and applicability 4) Integrate the evidence with clinical expertise, the client’s values and circumstances, and information from the practice context. 5) Evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency with which steps 1-4 were carried out and think about ways to improve your performance of them next time. 5 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 This process is explained in Hoffman et al. (2010) as the process of the 5 A’s: 1) Ask a question 2) Access the information 3) Appraise the articles found 4) Apply the information 5) Audit This process will be used throughout this report to inform and structure our approach. Ask a question To ensure this important first step of our process is well defined, specific and clear, we will be using the PICO framework which is suggested and supported by various authors ( (Cooke, et al., 2012) (Brettle & Grant, 2004)). Population: Adults with a primary diagnosis of depression Intervention: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Comparison: Treatment as usual Outcome: Reducing the symptoms experienced Our question will thus be structured as follows: Does the delivery method of CBT impact on the effectiveness in reducing symptoms for adults with a primary diagnosis of depression when compared with treatment as usual? 6 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Accessing the information To prevent problems arising in the future a good literature review will be conducted to underpin the entire problem solving process (Craig & Smyth, 2007). This is supported by Strauss et al. (2019) who stress that by taken an appropriate amount of time and making sure that the evidence is recent and up to date a structured and skilled search can be better achieved. To ensure this, Tomlin et al. (2002) suggest the identified research question is divided into its PICO/PIO component parts as can be seen in table 1 below. The different components have been listed below and account for spelling variations and synonyms of the used search terms as to not only include evidence that uses the UK spelling of certain words. Table 1: PIO structure Population Intervention Outcome Depressi* CBT Effective Depressive disorders Cognitive Behavio* Therapy Reduction Adults Delivery method Relapse Symptoms To ensure the search contained the combination of all these required details, we have made use of the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’. These can be defined as logical connectors used to formulate a search query and are now widely used in database searches to make these more specific to the query (Burris, 2018). Table 2 is an updated table 1 with Boolean operators included. 7 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Table 2: PIO components with Boolean operators Population Intervention Outcome CBT Depressi* ‘OR’ Depressive disorders Effective ‘ ‘ ‘OR’ A A N D ‘OR’ ‘ N Cognitive Behavio* Therapy D ‘ ‘OR’ Adults ‘OR’ Reduction ‘OR’ Relapse ‘OR’ Symptoms Delivery method A search strategy was utilized to guarantee that the results found in each of the 3 databases (Psycinfo, Cochrane Library Online and CINAHL) were of a good quality and a relevant nature (Holland, 2007). First each individual term was searched, however due to the vast amount of research this returned, an adjustment was made to start the search strategy for each database with a single component of the PIO structure linked together by the Boolean operator ‘OR’. Population was searched first, followed by Intervention and finally Outcome. Each database was then searched by combining the three different PIO components using the Boolean operator ‘AND’. This resulted initially in 5 journal articles on Psycinfo, 13 trials on the Cochrane Library and 3880 results on the CINAHL database. To reduce the amount of results in the CINAHL database filter criteria were utilized as shown in Table 3 and resulted in 11 applicable journal articles found. All search results can be found in Appendix A Table 3 Database filter criteria Publication date Main subject Location The studies needed to The main subjects of the The studies needed to be published in the last studies needed to be have been conducted in two years depression and CBT the UK and/or Ireland Age The studies were limited to ‘all adults’ 8 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 The screening of the remaining results involved reading the titles for applicability to our research question followed by ranking the quality of the remaining papers by utilizing the hierarchy of evidence (Sackett, et al., 1996)(figure 1) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) systematic review checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2020)(Appendix C). Figure 1: Hierarchy of Evidence After considering the above factors, the following systematic review was chosen to be critically appraised in this report: The process and delivery of CBT for depression in adults: a systematic review 9 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 and network meta-analysis ( López-López, et al., 2019). This systematic review had significant relevance to the posed research question. The authors conduct a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which a CBT intervention was used for treatment of adults with a primary diagnosis of depression ( López-López, et al., 2019). Appraise the article found The purpose of the López-López et al. (2019) study was to conduct a systematic review on RCTs in adults with a primary diagnosis of depression, where a CBT intervention was used. After screening and selection according to criteria, 91 studies were used to show the effectiveness of both the therapeutic delivery method, components and combination of components in CBT compared to treatment as usual (TAU). However, there was a substantial variation on how TAU was defined across the RCTs examined and thus findings would have to be interpreted with caution. Following the hierarchy of evidence (Sackett, et al., 1996), systemic reviews are considered the highest standard in terms of quality. However, this doesn’t automatically imply that each systemic review is of a high quality and thus validity, results and applicability still have to be critically appraised (Haber & LoBiondo-Wood, 2018). Critical appraisal is defined by O'Mathúna (2010) as the process of carefully and transparently evaluating the quality of published research reports and their relevance to a particular context. This definition can be achieved by utilising an appraisal tool so that the critical appraisal will be done in a structural way. However it is important to signify the experience and understanding of the appraiser of systematic reviews and how these can be best combined with the available structural tools (Evans & Pearson, 2001). The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2020) has over the years proven to be effective as an aid to appraising research literature and has been continuously updated by a team of experts with specific experience relating to each checklist. It was, however, recently reiterated via a user survey that the basic format continues to be appropriate and useful in practice. The specific systematic review checklist will be used to support the critical appraisal in this section to inform the discussion about internal and external validity of the chosen study. It has been added in Appendix C for reference. 10 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Internal Validity Internal validity can be defined as the extent to which a study establishes a reliable cause-and-effect relationship between a treatment and an outcome (Haber & LoBiondo-Wood, 2018). The application to our current study means that an appraisal would be made to which extent the application of CBT therapy methods and components would reduce the symptoms of an adult diagnosed with depression compared to TAU. The concept also means that possible alternative explanations can be excluded based on that finding (Haber & LoBiondo-Wood, 2018). López-López et al. (2019) chose to include all RCTs where the effectiveness of a CBT therapy technique was compared with TAU. This means that a wide array of techniques was accrued and thus techniques from both group and individual therapy as well as different delivery methods were pooled together. Initially this would seem that internal validity would be compromised due to not being able to effectively pinpoint which element of the techniques is effective in reducing symptoms (Coolican, 2009). The authors compensate for this decrease by using both Network meta-analysis (NMA) (Dias, et al., 2013) and component-level NMA (Welton, et al., 2009). NMA (Dias, et al., 2013) allows for multiple interventions to be pooled together from a set of RCTs and then compared on the level of two or more of those interventions. This would mean that if each combination of delivery method and components is considered a separate intervention, these interventions then could compared at the same time ( López-López, et al., 2019). The authors, however, rightly acknowledge that this wouldn’t be possible with a NMA due to the complexity of a CBT intervention. On the other hand, component-level NMA (Welton, et al., 2009) is succesful in comparing at this complex level and thus holds the possibility to address which aspect of the intervention has caused the specific decrease in symptoms. Implementation of NMA and component-level NMA should have mitigated some of the implications for our internal validity, however this would only be the case if all CBT interventions examined would be sufficiently detailed which wasn’t the case in some RCTs where only vague descriptions were available. Ultimately this means there is an adverse impact on internal validity due to this limitation. 11 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 High levels of performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) and detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment) were accounted for in most RCTs ( López-López, et al., 2019). This can be explained due to the nature of the therapeutic interventions and subsequently collaborative nature of the interaction between therapist and client. The client may change his responses to outcome measures due to being aware of his intervention and similarly, a therapist could incorporate his values or beliefs about a certain intervention. In both cases this would increase the possibility of heterogeneity of treatment results and thus this would negatively impact on the internal validity our systematic review (Haber & LoBiondo-Wood, 2018). The authors acknowledge this limitation, however, no measures were added to mitigate this effect. Internal validity was improved due to the presence of two authors independently screening abstracts and titles for eligibility for inclusion. If additional information was necessary, authors would be contacted for this purpose ( López-López, et al., 2019). In addition to this, both authors made use of the Cochrane risk of bias tool developed by Higgins et al. (2011) independently to assess risk of bias. The findings of Whiffin and Hasselder (2013) support the importance of the presence of two independently working reviewers and conclude this has a positive effect on both reducing the bias and improving the internal validity. Finally, additional uncertainty was introduced due to a combination of TAU definitions varying substantially both within and across studies, and the often not reported intensity of TAU in studies ( López-López, et al., 2019). One major drawback of this uncertainty is the impact on intervention effectiveness when compared and thus the significant negative effect on internal validity. 12 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 External validity External validity can be seen as a process to enable individual clinicians to reach conclusions as to whether it is relevant how they apply it to their own area of practice (Brettle & Grant, 2004). As a concept it deals with the applicability and generalizability of the study to other settings and thus is more tricky to quantify than internal validity (Hoffman, et al., 2010). The participants in this study are all adults above 18 who have a primary diagnosis of depression ( López-López, et al., 2019). The authors explain that to cover the broad spectrum of severity of depression symptoms for clients receiving therapy in outpatient settings, studies were both included with standardised diagnostic criteria like the different versions of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and validated depression questionnaires with a threshold to identify depression. The population presented in these studies can be seen as applicable to the population presenting at an IAPT service. An IAPT service also uses specific questionnaires like the PHQ-9 to ascertain whether a lower mood is classed as significant to receive therapy (The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2020). Even though the questionnaires used in the RCTs are different from the once used in an IAPT service, they are all validated outcome measures that have been empirically tested and therefore can be used to make similar assumptions about symptom reduction (Choi, et al., 2014). The external validity is reinforced due to the applicability of this population and is further reinforced due to most of the RCTs being conducted in the UK as well as excluding studies that focused on inpatients ( López-López, et al., 2019). On the other hand, the broad nature of the interventions offered is not applicable to a typical IAPT setting where NICE guidelines are followed for the treatment of depression (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009). The guidelines inform which CBT interventions should be implemented at certain severity level and treatment resistance of experienced depression symptoms. However, the CBT interventions in this systematic review are pooled together and include interventions both at low intensity and high intensity level, considering them equally effective on a broad range of depression symptoms at different severity levels ( López-López, et al., 2019). This would lower the applicability and implementation of the offered interventions and thus the external validity due to these not being specific enough to ascertain which to use at either low intensity or high intensity level. 13 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Discussion of results There was strong evidence present that CBT interventions provide a more significant decrease in depression scores at short term when compared to TAU ( López-López, et al., 2019). There was little evidence found of differential effectiveness of face-to-face compared to multimedia CBT interventions, additionally there was no strong evidence found of specific effects of any content components or combinations of components. Emphasis needs to be on the substantial uncertainty around effect estimates found for most intervention comparisons and outcomes including psychological placebo/attention. Once more the overall beneficial effect of CBT interventions have been shown to improve depressive symptoms and this has been replicated before in other studies (Richards and Richardson, 2012; Cuijpers and Gentili, 2017). Furthermore, multimedia CBT was found to be similarly effective as faceto-face CBT, although it is important to emphasise the considerable uncertainty in the treatment effect estimates showing no difference between face-to-face and multimedia CBT and thus caution needs to be exercised to see if the findings in regards to delivery method are clinically worthwhile to implement (Herbert, 2000). 14 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Recommendations The results provide sufficient evidence to make recommendations on how to implement changes in day to day practice in terms of the delivery method for CBT interventions for clients with a primary diagnosis of depression. It is, however, important to remain aware of the uncertainty in treatment effect sizes and small sample sizes and even though the report will continue to formulate a plan for implementation in the service, that is done under the premise that the following shortcomings have been addressed ( López-López, et al., 2019): 1) Large sample sizes will be needed in further studies when comparing face to face CBT with multimedia and hybrid CBT to account for the potential small differences expected. 2) Some of the complexity of CBT interventions have been addressed in the systematic review, however a further qualitative inquiry should be made to maximise the strength and possibilities of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. 3) An economic analysis can be done to make sure that the proposed changes would be cost effective for the service and beneficial for clients presenting with depressive symptoms. 4) Clinical tests to be done in a more ‘naturalistic’ environment like a local IAPT service. 15 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Apply the information The knowledge we have obtained needs to now be transferred into clinical practice. It is important that any change made to IAPT services should only be started when it is founded on evidence based findings and first and foremost with the interests of clients at its heart (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020). To implement change, we need to understand the process of change and how to manage this. A variety of models are available to help implement these changes. Lewin’s (1951) Model of Organisational Change explains how barriers to change results in a ‘frozen’ state. To identify driving and restraining forces the ‘Unfreezing’ state is involved and this leads subsequently to a proposed guidance for the management part. Finally, successful implementation of the management part allows the change to happen which will then become the new ‘frozen’ state. Figure 2: Process of Organisational Change Lewin (1951) Old State FROZEN Un-freeze Change Re-freeze New State FROZEN The driving and restraining forces that support the unfreezing state are researched and applied in a Force Field Analysis (Lewin, 1951) (Appendix D). This will make sure that when a change plan (Appendix E) is implemented the adoption of new practices informed by EBP will be made more smooth due to already being aware and having measures ready for reducing difficult situations (Winch, et al., 2005). 16 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Audit There are however many potential difficulties to the application of research into practice. For example, resistance to change in practice may arise from both the clinician and patient, if the patient’s needs are not holistically being met (Couvillion, 2005). Ongoing evaluation is therefore important because it allows the monitoring of the change and gives the opportunity to make changes if things are not working (Haber & LoBiondo-Wood, 2018). The change can be monitored by collecting the outcomes from the PHQ-9 (The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2020) in a systematic way and evaluating these for the effectiveness of the different delivery methods. It is important to include revisiting of the research in this cycle to ensure that new information can be used to make the implemented changes not outdated (Craig & Smyth, 2007). 17 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Conclusion By answering our research question we have been able to conclude that other delivery methods than face to face are potentially as effective. As stressed before, it is important to keep the limitations of the study in mind and to apply further research and evidence before implementing this fully into practice ( López-López, et al., 2019). When making these recommendations, it was felt that these limitations could be addressed and the potential benefits for clients and colleagues alike could be felt as a positive change and cost effective intervention within the service. 18 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 References López-López, J. A. et al., 2019. The process and delivery of CBT for depression in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, Volume 49, p. 1937–1947. American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington: Author. Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F. & Emery, G., 1987. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Brettle, A. & Grant, M., 2004. Finding the evidence for practice: a workbook for health professionals. London : Churchill Livingstone. Burris, S., 2018. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. [Online] Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/boole/ [Accessed 28 October 2020]. Choi, S. W., Schalet, B., Cook, K. F. & Cella, D., 2014. Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: Linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS Depression. Psychological Assessment , 26(2), pp. 513-527. Cooke, A., Smith, D. & Booth, A., 2012. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), pp. 1435-1443. Coolican, H., 2009. Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology. London: Hodder Education. Couvillion, J., 2005. How to promote or implement Evidence-based practice in a clinical setting. Home health care management practice, Volume 17, p. 269. Craig, J. & Smyth, R., 2007. The Evidence-Based Practice Manual for Nurses. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2020. CASP checklists. [Online] Available at: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Systematic-Review-Checklist2018_fillable-form.pdf [Accessed 28 October 2020]. Cuijpers, P. & Gentili, C., 2017. Psychological treatments are as effective as pharmacotherapies in the treatment of adult depression: a summary from Randomized Clinical Trials and neuroscience evidence. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, Volume 20, p. 147– 152. Cuijpers, P. et al., 2013. Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 3(4). 19 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Dias, S., Sutton, A., Ades, A. & Welton, N., 2013. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.. Medical Decision Making, Volume 33, pp. 607-617. Evans, D. & Pearson, A., 2001. Systematic Reviews: Gatekeepers of Nursing Knowledge. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 10(5), pp. 593-599. Fernández, A. et al., 2007. Treatment adequacy for anxiety and depressive disorders in six European countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, Volume 190, pp. 172-173. Fineout-Overholt, E., Melnyk, B. M. & Schultz, A., 2005. Transforming Health Care from the Inside Out: Advancing Evidence-Based Practice in the 21st Century. Journal of Professional Nursing, 21(6), pp. 335-344. Haber, J. & LoBiondo-Wood, G., 2018. Nursing research: methods and critical appraisal for evidencebased practice. 9th ed. St Louis: Elsevier. Harris, E. C. & Barraclough, B., 1997. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, Volume 170, pp. 205-228. Herbert, R. D., 2000. How to estimate treatment effects from reports of clinical trials. I: Continuous outcomes. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 46(3), pp. 229-235. Higgins, J. et al., 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal, Volume 343. Hoffman, T., Bennet, S. & Del Mar, C., 2010. Evidence based practice across the health professions. 3rd Edn, Elsevier, Australia.. 3rd ed. Chatswood: Elsevier Australia. Holland, M., 2007. Advanced searching: Researcher guide. Bournemouth: Bournemouth University. Judd, L. J., 1997. The Clinical Course of Unipolar Depressive Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, Volume 54, pp. 989-991. Kohn, R., Saxena , S., Levav , I. & Saraceno, B., 2004. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of World Health Organisation, Volume 82, pp. 858-866. Lewin, K., 1951. Field Theory in Social Science. New York: Harper Row. Louch, P., 2009. Understanding the Impact of Depression.. Practice Nurse, Volume May, pp. 43-51. Lovell, K. & Richard, D., 2000. Multiple Access Points and Levels of Entry (MAPLE): Ensuring Choice, Accessibility and Equity for CBT Services. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, Volume 28, pp. 379 -391. 20 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Mind, 2019. Depression. [Online] Available at: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-healthproblems/depression/about-depression/ [Accessed 27 October 2020]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009. Depression in adults: recognition and management. [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 [Accessed 27 October 2020]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020. Guidance and advice list. [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/published?type=apg,csg,cg,cov,mpg,ph,sg,sc [Accessed 27 October 2020]. O'Mathúna, D. P., 2010. TIPS AND TRICKS: Critical appraisal of systematic reviews. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(4), pp. 414-418. Public Health England, 2019. Public Health England. [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file /779473/state_of_the_north_east_2018_public_mental_health_and_wellbeing.pdf [Accessed 27 October 2020]. Richards, D. & Richardson, T., 2012. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, Volume 32, p. 329–342. Sackett, D. et al., 1996. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal, Volume 312, pp. 71-72. Steinert , C., Hofmann, M., Kruse, J. & Leichsenring, F., 2014. Relapse rates after psychotherapy for depression – stable long-term effects? A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 168, pp. 107-118. Strauss, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W. & Haynes, R. B., 2019. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 5th ed. s.l.:Elsevier Limited. The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2020. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Manual. [Online] Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/iapt-manual-v4.pdf [Accessed 27 October 2020]. Tomlin, A., Dearness, K. & Badenoch, D., 2002. Enabling evidence-based change in health care. Evidence-Based Mental Health, Volume 5, pp. 68-71. 21 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Welton, N., Caldwell, D., Adamopoulos, E. & Vedhara, K., 2009. Mixed treatment comparison metaanalysis of complex interventions: psychological interventions in coronary heart disease. American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 169, p. 1158–1165. Whiffin, C. & Hasselder, A., 2013. Making the link between critical appraisal, thinking and analysis. British Journal of Nursing, 22(14), pp. 831-835. Whitfield , G. & Williams, C., 2003. The evidence base for cognitive behavioural therapy in Depression. Delivery in busy clinical settings. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, Volume 9, pp. 2130. Winch, S., Henderson, A. & Creedy, D., 2005. Read, Think, Do!: a method for fitting research evidence into practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, Volume 50, p. 20–26. World Health Organisation, 2020. Depression. [Online] Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Accessed 27 October 2020]. 22 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Appendix Appendix A: Search results for each database Psychinfo 23 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 The Cochrane Library Online 24 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 CINAHL 25 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Appendix B: Chosen research paper ( López-López, et al., 2019) 26 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 27 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 28 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 29 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 30 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 31 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 32 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 33 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 34 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 35 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 36 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Appendix C: CASP Systematic Review Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2020) 37 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 38 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 39 Davy De Geeter V8386530 EBP Summative Assessment RMH4008 Appendix D: Force Field Analysis Driving forces Restraining forces NICE guidelines Minimal staff training needed Cost effective alternatives Research that has been critically examined Good amount of staff available All change is difficult and staff might be resistant Even though it will be more cost effective, money will have to be spent to make the changes Quality of the research had further recommendations before implementation was possible Appendix E: Change plan 1) Arrange meeting to discuss evidence and suggested changes to clinical practice with leadership team. 2) Assess and discuss potential costs for implementing this change if first approval given. 3) Get approval from leadership team for implementation of digital CBT. 4) Inquire if colleagues would be interested in joining a task force to set up the change if previous step is accepted 5) Lead of task force to propose further research to be discussed and assessed before implementation of clinical practice and to inform practical changes. 6) Design and implement new guidance for digital therapy. Make sure to seek ideas from both the task force as well as leadership team and other colleagues to prevent smooth implementation and non involvement. 7) Implement digital therapy with small team and collect PHQ-9 outcomes over a period of 3 months. 8) Evaluate outcomes and review further steps if needed. 9) Continue step 2-8 as needed for further implementation and to make impact in wider team. 40