Penrose's Insights in Strategic Management & International Business

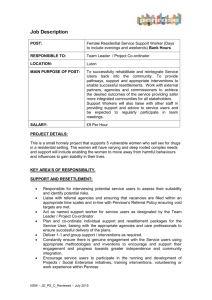

advertisement