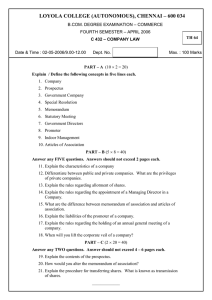

(For private circulation ONLY) THE LAW OF BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONS Section 1 of the Companies 2012 states what company means as a company formed and registered under this Act or an existing company or a re-registered company under this Act. This is a very vague definition, in the statute the word company is not a legal term hence the vagueness of the definition. The legal attributes of the word company will depend upon a particular legal system. In legal theory company denotes an association of a number of persons for some common object or objects. In ordinary usage it is associated with economic purposes or gain. A company can be defined as an association of several persons who contribute money or money’s worth into a common stock and who employ it for some common purpose. Differences between companies and other legal entities A company differs from other entities like partnerships, associations, co-operative societies, nongovernmental organisations, unregistered associations in many respects. Company and partnerships. The law treats companies in company law distinctly from partnerships in partnership law. Company . It is created upon registration in accordance with the Companies Act Partnerships Is formed by agreement of the partners of the partners. Registration is optional For a private company, it is one which limits the number of its members to 100 not including the company's former and current employees (S.5). Section 6 provides that a company that is not a private company under section under section 5 is a public company One person can form a company The membership is restricted to 2 or more persons and not more than 20 for trade and business. However, professional partnerships have a maximum of 50 members . It attains a separate legal existence upon incorporation . The partnership has no separate legal existence, it’s the same as its partners, applying law of agency The minimum number is two. . The property acquired Property belongs to the partners belongs to the company A member or director may enter into a The partner cannot enter into a contract with contract with the company the firm Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 1 The company debts are the company’s The partners are responsible for the responsibility, and not for the shareholder partnership debts The shareholder is not an agent of the The partner is an agent of the firm company The liability of members is limited either by shares or guarantee except for unlimited companies The shares in a public company are freely transferable Companies have perpetual succession The company is managed by a board of directors elected by the shareholders The company is formed using the memorandum and articles of association Liability in partnership is unlimited except for the limited liability partnerships The shares of the partnership can only be transferred with the partners’ consent Death, insanity, insolvency of a partner terminates the partnership unless otherwise agreed The partnership is managed by all partners The major document is the partnership deed or the partnership Act FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS OF COMPANY LAW There are two fundamental legal concepts The concept of legal personality; (corporate personality) by which a company is treated in law as a separate entity from the members. The concept of limited liability; Concept of legal personality (i) A legal person is not always human, it can be described as any person human or otherwise who has rights and duties at law; whereas all human persons are legal persons not all legal persons are human persons. The non-human legal persons are called corporations. The word corporation is derived from the Latin word Corpus which inter alia also means body. A corporation is therefore a legal person brought into existence by a process of law and not by natural birth. Owing to these artificial processes they are sometimes referred to as artificial persons not fictitious persons. LIMITED LIABILITY Basically liability means the extent to which a person can be made to account by law. He can be made to be accountable either for the full amount of his debts or else pay towards that debt only to a certain limit and not beyond it. In the context of company law liability may be limited either by shares or by guarantee. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 2 Under Section 4(2) (a) of the Companies Act, in a company limited by shares the members liability to contribute to the companies assets is limited to the amount if any paid on their shares. Under Section 4 (2) (b) of the Companies Act in a company limited by guarantee the members undertake to contribute a certain amount to the assets of the company in the event of the company being wound up. Note that it is the members’ liability and not the companies’ liability which is limited. As long as there are adequate assets, the company is liable to pay all its debts without any limitation of liability. If the assets are not adequate, then the company can only be wound up as a human being who fails to pay his debts. Nearly all statutory rules in the Companies Act are intended for one or two objects namely i. The protection of the company’s creditors; ii. The protection of the investors in this instance being the members. These underlie the very foundation of company law. FORMATION OF A REGISTERED COMPANY A company may either be a statutory, chartered or registered company. The latter, formed under the Companies Act is the commonest. This is by registration under the Companies Act . In order to form a registered company, the promoters have to choose between a limited and unlimited company. The disadvantage with an unlimited company is that members will ultimately be personally liable for its debts and for this reason they are likely to be wary of it if it intends to trade. A limited company on the other hand distinguishes ownership from management enabling expertise and to stop the tendency of saying “this is my company, I can do whatever I want.” If the promoters decide upon limited liability, then they have to decide on whether to be limited by shares or guarantee. This is determined by the purpose which the company is to perform. A guarantee company is more suitable for a non-profit making company. The question if whether the company should have a share capital does not arise for a company limited by shares or guarantee. If the company is unlimited it may or may not have its capital divided in to shares depending on its purpose. If it is intended to make and distribute profits, a share capital is more appropriate. S. 4 of the Companies Act provides; (1) Any one or more persons may for a lawful purpose, form a company, by subscribing their names to a memorandum of association otherwise complying with the requirements of this Act in respect of registration, form an incorporated company, with or without limited liability. Subsection 2 defines. a. Company limited by shares; a company having the liability of its members limited by the memorandum to the amount, if any, unpaid on the shares respectively held by them. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 3 b. Limited by guarantee; a company having the liability of its members limited by the memorandum to the amount that the members undertake in the memorandum to contribute to the assets of the company if it is being wound up, c. Unlimited company; a company not having any limit on the liability of its members Further, the promoters have to choose between a public company and a private company. These fulfill different economic purposes. The former to raise capital from the public to run the corporate enterprise and the latter to confer a separate legal personality on the business of a single trader or a partnership. The incorporators may have the ultimate ambition of going public but rarely will they be in a position to do so immediately. If however, they are, then the company will have to be limited by shares. The memorandum of association will have to state that it is to be a public company and special requirements as to its registration will have to be complied with. Another company will be a private company. A private company is defined by S.5 of the companies Act to mean; (1) A “private company” means a company which by its articles— (a) restricts the right to transfer its shares and other securities; (b) limits the number of its members to one hundred, not including persons who are employed by the company and persons who, have been formerly employed by the company; and (c) prohibits any invitation to the public to subscribe for any shares or debentures of the company. (2) Where two or more persons hold one or more shares in a company jointly, they shall, for the purposes of this section, be treated as a single member. S.6 defines a public company as one is not a private company under section 5. From the above, the classification of a registered company is a s follows; i. ii. iii. iv. A limited company either by shares or guarantee An unlimited company A public company A private company. In order to incorporate themselves into a company, those people wishing to trade through the medium of a limited liability company must first prepare and register certain documents. These are as follows Memorandum of Association: this is the document in which they express inter alia their desire to be formed into a company with a specific name and objects. The Memorandum of Association of a company is its primary document which sets up its constitution and objects; Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 4 Articles of Association; whereas the memorandum of association of a company sets out its objectives and constitution, the articles of association contain the rules and regulations by which its internal affairs are governed dealing with such matters as shares, share capital, company’s meetings and directors among others; The requirements regarding the memorandum of association are provided for under S. 7 of the Companies Act. 7. (1) The memorandum of every company shall be printed in the English language and shall state— (a) the name of the company, with “limited” as the last word of the name in the case of a company limited by shares or by guarantee; (b) that the registered office of the company is to be situated in Uganda; and (c) may also state the objects of the Company. (2) The memorandum of a company limited by shares or by guarantee must also state that the liability of its members is limited. (3) The memorandum of a company limited by guarantee must also state that each member undertakes to contribute to the assets of the company if it is being wound up while he or she is a member or within one year after he or she ceases to be a member, for payment of the debts and liabilities of the company contracted before he or she ceases to be a member and of the costs, charges and expenses of winding up and for adjustment of the rights of the contributories among themselves such amount as may be required, not exceeding a specified amount. (4) In the case of a company having a share capital— (a) the memorandum must also, unless the company is an unlimited company, state the amount of share capital with which the company proposes to be registered and the division of that share capital into shares of a fixed amount; (b) a subscriber of the memorandum may not take less than one share; and (c) each subscriber shall write opposite his or her name the number of shares he or she takes. (5) Notwithstanding subsection (1)(c), where the company’s memorandum states that the object of the company is to carry on business as a general commercial company the memorandum shall state that— (a) the object of the company is to carry on any trade or business whatsoever; and (b) the company has power to do all such things as are incidental or conducive to the carrying on of any trade or business by it. S. 8. Provides for the Signature of memorandum. (1) The memorandum shall be dated and shall be signed by each subscriber in the presence of at least one attesting witness who shall state his or her occupation and postal address. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 5 (2) Opposite the signature of every subscriber there shall be written in legible characters his or her full name, occupation and postal address. The Companies Act puts restrictions on the amendment of the memorandum. This provided for under S.9. which states that . A company may not alter the conditions contained in its memorandum except in the cases in the mode and to the extent for which express provision is made in this Act. The mode for alteration of the Company’s objects is provided for under S. 10 which states that; A company that has included in its memorandum its objects, may, by special resolution, alter its memorandum with respect to the objects of the company. But this must be for the benefit of the company to carry out business more economically and efficiently. The same applies to Articles of association under S. 11 and which can also be altered by a special resolution under S. 16. However, its not mandatory to register the articles of association. Registration; S. 18 provides that (1) A company shall be registered by filling in the particulars contained in the registration form in the second schedule to the Act. S.19 (1) The memorandum and the articles, if any, shall be delivered to the registrar and he or she shall retain and register them and shall assign a registration number to each company so registered. (2) A company shall indicate its registration number on all its official documents. Under S. 18 (3) On registration of the company, the registrar shall issue a certificate signed by him or her that the company is incorporated and in the case of a limited liability company, that the company is limited. This certificate issued by the registrar is under S. 22 taken be conclusive evidence that all the requirements of this Act in respect of registration and of matters precedent and incidental to registration have been complied with and that the association is a company authorized to be registered and duly registered under the Act. Therefore its upon registration that the company is born and can commence business. Membership. This is provided for under S. 47 of the Act which provides; That (1) The subscribers to the memorandum of a company shall be taken to have agreed to become members of the company, and on its registration shall be entered as members in its register of members. (2) A person who agrees to become a member of a company, and whose name is entered in its register of members shall be a member of the company. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 6 This means that a member is one who subscribes to the memorandum of association, or one who is later admitted after incorporation. If a person is not entered on the register yet he or she is a member, the remedy is provided for under S. 125 whereby court has the power to rectify the register and payment by the company of any damages sustained by any party aggrieved CORPORATE PERSONALITY The subscribers to the memorandum of association together with such other persons become members of a body corporate by the name included in the certificate of incorporation; they constitute a company. This in a way establishes the legal personality of a company where the individuals cease to enforce their rights or obligations as individuals and now act collectively as a body corporate. The natural persons behind this corporation are now referred to by the name indicted in the certificate of incorporation. The law creates an artificial person which is a juridical entity with ability to have legal rights and incur legal liabilities. A corporation therefore, is a legal entity distinct from its members, capable of enjoying rights being subject to duties which are not the same as those enjoyed or borne by the members. The full implications of corporate personality were not fully understood till 1897 in the case of; Salomon v. Salomon [1897] A C 22 Facts of the case Salomon was a prosperous leather merchant who specialized in manufacturing leather boots. For many years he ran his business as a sole trader. By 1892 his sons had become interested in taking part in the business. Salomon decided to incorporate his business as a limited liability company Salomon and Co ltd and he then sold his business to the new company. At the time the legal requirement was that at least seven persons subscribe as members of a company and these were Salomon, his wife, daughter and four sons. He had sold his business to the company at the price of £39,000 satisfied by £9000 in cash, £10,000 in debentures conferring a charge on the company’s assets and £20,000 in fully paid up £1 shares. Salomon was both a creditor because he held a debenture and also a shareholder because he held shares in the company. The company share capital was £40,000 divided into 40,000 shares of £1 each. Seven shares were then subscribed for in cash by Salomon, his wife and daughter and each of his 4 sons. Salomon therefore had 20,001 shares in the company and each member of the family had 1 share as Salomon‘s nominees. The company appointed directors with Mr. Salomon and his two sons appointed as directors and they were in charge of managing the overall control with Salomon. Immediately after the transfer of the business to the company, there was a depression in the boot industry and government failed to honour obligtions to the company in time and the profitability of the company began to decline. Mr. Salomon and wife advanced money to the company to salvage it from the financial crisis but Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 7 it failed to recover. He cancelled his debentures and the company entered into another agreement creating debentures with Mr. Broderip who became a secured creditor of the company. It still failed to recover and Mr Broderip appointed a receiver under the debentures. Thereafter, the company went into liquidation and a liquidator was appointed to realise cash and pay creditors of the company. Mr Broderip and Salomon raised their claims as secured creditors but the sale out of the company assets could not sufficiently cover all the creditors. The liquidator then rejected the claims of Broderip and Salomon arguing that they were fraudulent and invalid. At the trial court, the claims of Broderip were settled but rejected the claims of Salomon and held.; That the company was a mere sham an alias, agent or nominee of Salomon and was actually Salomon in another form; That Mr. Salomon should therefore indemnify the company against its trade loss as the company was his agent. The basis of the trial court was that; Salomon had control over the company by owning 20001 shares as a majority shareholder; that the rest of the shareholders did not ay for their shares as they w ere paid by Salomon hence were mere nominees.; that the same business conducted by Salomon as sole trader was the same; that people running the business was Salomon as the manager who determined the price that was paid to him; that Salomon issued debentures when he was an insider to make him a secured creditor. Mr. Salomon then appealed; The Court of Appeal unanimously agreed that the trader should be made liable but they concentrated their judgments on the ground that the use to which the Companies Act had been put was improper. That the formation of the company and the issue of debentures to mr. Salomon were a mere scheme to enable him carry on business in the name of the company with limited liability contrary to the true intent and meaning of the companies Act and further to enable him to obtain a preference over other creditors of the company by securing a charge on the assets of the company by means of debentures. The tenor of the Court of Appeal decision is encapsulated in the judgment of Lopes LJ, who first lamented that; It would be lamentable if a scheme like this could not be defeated; if we were to permit it to succeed, we should be authorizing a perversion of the Companies Act; we should be giving vitality to that which is a myth and a fiction. The transaction is a device to apply the machinery of the Companies At to a state of things never contemplated by the Act. it never was intended that the company be constituted of one substantial person and six mere dummies, the nominees of that person without any real interest in the company. He then stated that; The Act contemplated the incorporation of seven independent bona fide members, who had a mind and will of their own, and were not the mere puppets of an individual who, adopting Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 8 the machinery of the Act, carried on his old business in the same way as before, when he was a sole trader. To legalise such a transaction would be a scandal. The public policy behind the Court of Appeal decision was to protect innocent parties who transact business with the company against the fraudulent or unfair transactions of insiders. Lindley LJ while agreeing that there was a company, treated it as a trustee improperly brought into existence by Salomon to enable him to do what the statute prohibits. His liability rests on the purpose for which he formed the company, on the way he formed it, and on the use which he made of it. The company was a device to enable him carry out business with limited liability and issue debentures to himself in order to defeat the claims of those who have been incautious enough to trade with the company without perceiving the trap which he has laid for them…Mr, Salomon’s scheme is a device to defraud creditors. …the so called sale of the business to the company was a mere sham and could be set aside in the interests of its creditors. The Court of Appeal went on to suggest that, rather than an agent, the company was a trustee holding business on trust for Salomon the beneficiary. That the rest of the family members were mere dummies and the company was a trustee of Mr. Salomon who was a beneficiary ad as such Salomon had to indemnify the trustee, the company. On appeal to the House of Lords; The House of Lords unanimously reversed the Court of Appeal and held that; Upon incorporation a company is at law a different person altogether from the subscribers to the memorandum of association. Even if it is the same business as precisely before and the same persons are the managers and the same hands receive the profits, the company is not in law the agent of the subscribers or trustees for the them. That the subscribers as members are not liable in any shape or form except as provided by the Act. there is nothing in the Act that provides that the subscribers must be independent and not related as long as the requirements of incorporation are complied with. In the words of Lord Halsbury “Either the limited company was a legal entity or it was not. If it was, the business belonged to it and not to Salomon. If it was not, there was no person and no thing at all and it is impossible to say at the same time that there is a company and there is not” page 31 In the words of Lord Mcnaghten “the company is at a law a different person altogether from the subscribers and though it may be that after incorporation the business is precisely the same as it was before, and the same persons are managers, and the same hands receive the profits, the company is not in law the agent of the subscribers or trustee for them nor are the subscribers as members Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 9 liable in any shape or form except to the extent and manner prescribed by the Act … in order to form a company limited by shares the Act requires that seven (7) persons who are each to take one share at least should sign a Memorandum of Association. If those conditions are satisfied, what can it matter, whether the signatories are relations or strangers? There is nothing in the Act requiring that the subscribers to the Memorandum should be independent or unconnected or that they or anyone of them should take a substantial interest in the undertaking or that they should have a mind and will of their own. When the Memorandum is duly signed and registered though there be only seven (7) shares taken the subscribers are a body corporate capable forthwith of exercising all the functions of an incorporated company. … The company attains maturity on its birth. There is no period of minority and no interval of incapacity. A body corporate thus made capable by statutes cannot lose its individuality by issuing the bulk of its capital to one person whether he be a subscriber to the Memorandum or not.” (page 51) Lord Halsbury; It seems to me impossible to dispute that once the company is legally incorporated it must be treated like any other independent person with its rights and liabilities appropriate to itself, and that the motives of those who took part in the promotion of the company are absolutely irrelevant in discussing what those rights and liabilities are. (page 30) Lord Herschell further noted on page 43 that; In a popular sense, a company may in every case be said to carry on business for and on behalf of its share-holders; but this certainly does not in point of law constitute the relation of principal and agent between them or render the shareholders liable to indemnify the company against the debts which it incurs. Lord Davey on page 56 notes; I observe, in passing, that nothing turns upon there being only one person interested. The argument would have been just as good if there had been six members holding the bulk of the shares and one member with a very small interest, say, one share. I am at a loss to see how in either view taken in the Courts below the conclusion follows from the premises, or in what way the company became an agent or trustee for the appellant, except in the sense in which every company may loosely and inaccurately be said to be an agent for earning profits for its members, or a trustee of its profits for the members amongst whom they are to be divided. There was certainly no express trust for the appellant; and an implied or constructive trust can only be raised by virtue of some equity…Nor do I think it legitimate to inquire whether the interest of any member is substantial when the Act has declared that no member need hold more than one share, and has not prescribed any minimum amount of a share. Lord Macnaghten gave the purpose of limited liability; Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 10 Among the principal reasons which induce persons to form private companies, as is stated very clearly by Mr. Palmer in his treatise on the subject, are the desire to avoid the risk of bankruptcy, and the increased facility afforded for borrowing money. By means of a private company, as Mr. Palmer observes, a trade can be carried on with limited liability, and without exposing the persons interested in it in the event of failure to the harsh provisions of the bankruptcy law. A company, too, can raise money on debentures, which an ordinary trader cannot do. Any member of a company, acting in good faith, is as much entitled to take and hold the company's debentures as any outside creditor. Every creditor is entitled to get and to hold the best security the law allows him to take. The above passage by Lord Macnaghten states the public policy behind the decision that is ; to encourage business, protect people from risk of business, promotion of trade (capitalism) and the concept of constructive notice as creditors should make inquiries. Lord Watson stated the need for inquiries on page 40 that; The unpaid creditors of the company, whose unfortunate position has been attributed to the fraud of the appellant, if they had thought fit to avail themselves of the means of protecting their interests which the Act provides, could have informed themselves of the terms of purchase by the company, of the issue of debentures to the appellant, and of the amount of shares held by each member. In my opinion, the statute casts upon them the duty of making inquiry in regard to these matters. Whatever may be the moral duty of a limited company and its share-holders, when the trade of the company is not thriving, the law does not lay any obligation upon them to warn those members of the public who deal with them on credit that they run the risk of not being paid. One of the learned judges asserts, and I see no reason to question the accuracy of his statement, that creditors never think of examining the register of debentures. But the apathy of a creditor cannot justify an imputation of fraud against a limited company or its members, who have provided all the means of information which the Act of 1862 requires; and, in my opinion, a creditor who will not take the trouble to use the means which the statute provides for enabling him to protect himself must bear the consequences of his own negligence. The significance of the Salomon decision is threefold. The decision established the legality of the so called one man company; It showed that incorporation was as readily available to the small private partnership and sole traders as to the large private company. It also revealed that it is possible for a trader not merely to limit his liability to the money invested in his enterprise but even to avoid any serious risk to that capital by subscribing for debentures rather than shares. Since the decision in Salomon’s case the complete separation of the company and its members has never been doubted. This was further fortified in the case of lee v lee Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 11 Lee v Lee’s Air Farming Ltd. (1961) A.C. 12 Lee’s company was formed with capital of £3000 divided into 3000 £1 shares. Of these shares Mr. Lee held 2,999 and the remaining one share was held by a third party as his nominee. In his capacity as controlling shareholder, Lee voted himself as company director and Chief Pilot. In the course of his duty as a pilot he was involved in a crash in which he died. His widow brought an action for compensation under the Workman’s Compensation Act and in this Act workman was defined as “A person employed under a contract of service” so the issue was whether Mr. Lee was a workman under the Act and whether there was a master-servant relationship? The House of Lords Held: “ ... That it was the logical consequence of the decision in Salomon’s case that Lee and the company were two separate entities capable of entering into contractual relations and the widow was therefore entitled to compensation.” That it is well established that the mere fact that someone is a director of a company is no impediment to his entering into a contract to serve the company. The company and the deceased were separate legal entities,. The company had the right to decide what contracts for aerial top dressing it would enter into. The deceased was the agent of the company in making the necessary decisions. The deceased was a worker and his position as a sole governing director did not make it impossible for him to be the servant of the company in the capacity of a chief pilot. In his words, Lord Morris stated; A man acting in one capacity can give orders to himself in another capacity; and also a man acting in one capacity can make a contract with himself in another capacity; There have been a number of other cases decided invoking the decision in Salomon v Salomon. These cases highlight the consequences of corporate personality. Consequences or attributes of Corporate personality 1. The company is a legal entity, distinct from its members hence capable of enjoying rights and incur liabilities. See Salomon v Salomon. To import the words of Lord Halsbury; Once the company is legally incorporated it must be treated like any other independent person with its rights and liabilities appropriate to itself, and that the motives of those who took part in the promotion of the company are absolutely irrelevant in discussing what those rights and liabilities are. (page 30) 2. A company can enter into a contract with one of its own; lee v lee 3. Company property belong to the company and not its members; Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 12 Macaura V. Northern Assurance Co. Ltd (1925) A.C. 619 The Appellant owner of a timber estate assigned the whole of the timber to a company known as Irish Canadian Saw mills Company Limited for a consideration of £42,000. Payment was effected by the allotment to the Appellant of 42,000 shares fully paid up in £1 shares in the company. No other shares were ever issued. The company proceeded with the cutting of the timber. In the course of these operations, the Appellant lent the company some £19,000. Apart from this the company’s debts were minimal. The Appellant then insured the timber against fire by policies effected in his own name. Then the timber was destroyed by fire. The insurance company refused to pay any indemnity to the appellant on the ground that he had no insurable interest in the timber at the time of effecting the policy. The courts held that it was clear that the Appellant had no insurable interest in the timber and though he owned almost all the shares in the company and the company owed him a good deal of money, nevertheless, neither as creditor or shareholder could he insure the company’s assets. That when Macaura sold the property to the company he ceased to enjoy any legal or equitable interest in it. The property was wholly and completely owned by the company. Lord Buckmaster; No shareholder has any right to any item of property owned by the company for he has no legal or equitable interest therein. If his contention were right, it would follow that any person would be at liberty to insure the furniture of his debtor and no such claim has ever been recognized by the courts. However, courts have been of the view that a person can have an insurable interest in the property of the company if such person is the only shareholder and creditor of the company, and in such case, Macaura should not be followed. This was held in the case below; Kosmopoulos v Constitution Insurance co of Canada (1987) 1 SCR 2 Mr. Kosmopoulos had a leather goods company for which he was the sole shareholder and director. His lease for the company office was under his own name from when he originally ran the business as a sole proprietor. The insurance on the office, however, was in his own name. His insurance agency knew that he was under the lease and himself but carried on business as a corporation. A fire in a neighbouring lot damaged his office; however, the insurance company refused to cover his damages At trial, the judge held that Mr. Kosmopoulos could not recover damages as owner for the assets of the business as they were owned by the company and not him, but that he could recover as insured because of his insurable interest in the building. This ruling was upheld on appeal, with the court noting that as companies could, thanks to recent laws, have a sole shareholder, Macaura could be restricted to cases involving multiple shareholders. On appeal to the House of Lords Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 13 The issue before the Court was whether the assets of Mr. Kosmopoulos, as shareholder, were covered by the insurance. The Court upheld the ruling of the lower courts. First of all, the Court decided that this was not a situation where they should "lift the corporate veil". That the corporate veil should not be lifted here even though theoretically could be lifted to do justice. Those who have chosen the benefits of incorporation must bear the corresponding burdens and if the veil is to be lifted it should only be done in the interests of third parties who would otherwise suffer as a result of the choice. Macaura should not be followed if an insured can demonstrate some relation to or concern in the subject of insurance which relation or concern by the happening of perils injured against may be so affected as to produce a damage detriment or prejudice to the person insuring. (factual expectancy test). However, the court found that the owner, as insured, held an insurable interest in the assets—that is, he had enough of a link to the assets to validly insure them. Lord Mclntyre J; The Macaura rule should not be accepted to compel a holding that a sole shareholder and sole director of a company could not have an insurable interest in the assets of the company. Modern company law now permits the creation of companies with one shareholder. The identity then between the company and that sole shareholder and director is such that an insurable interest in the company’s assets may be found in the sole shareholder. The above case, means that Macaura could be restricted only to cases involving multiple shareholders and creditors. A company may acquire property in its own name and is capable of possessing property. Hindu Dispensary, Zanzibar v NA Patwa and Sons [1958] 1 EA 74 The Zanzibar Rent Restriction Board, having found that a flat owned by the respondents had remained unoccupied for more than one month without good cause, allocated the flat to the appellant under s. 7 (1) (l) (i) of the Rent Restriction Decree, 1953, The flat was allocated to the appellant for the purpose of housing a doctor to be employed by the appellant in its business. The respondents appealed to the High Court which allowed the appeal on the ground that a body corporate could not be a “suitable tenant” under the Rent Restriction Decree. On a second appeal it was contended that since the Decree applies to both business premises and dwelling houses the flat though intended to be occupied as a dwelling was qua the appellant “business premises”; and that a body corporate could be a “suitable tenant” of business premises under s. 7 (1) (l) (i) of the Decree. Held; (i) since the Rent Restriction Decree also applied to business premises a trading company could be a “suitable tenant” of premises for the purposes of its business. ( ii) the suit premises, though intended to be occupied as a dwelling house were qua the Dispensary “business premises”. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 14 Per Curiam– “A company can have possession of business premises by its servants or agents. In fact that is the only way it can have physical possession.” 4. As an artificial person, a company has no racial attributes; Katate v Nyakatukura (1956) 7 U.L.R 47A The Respondent sued the Petitioner for the recovery of certain sums of money allegedly due to the Ankole African Commercial Society Ltd in which the petitioner was a Director and also the Deputy Chairman. The Respondent conceded that in filing the action he was acting entirely on behalf of the society, which was therefore the proper Plaintiff. The action was filed in the Central Native Court. Under the Relevant Native Court Ordinance the Central Native Court had jurisdiction in civil cases in which all parties were natives. The issue was whether the Ankole African Commercial Society Ltd of whom all the shareholders were natives was also a native. The court held that a limited liability company is a corporation and as such it has existence that is distinct from that of the shareholders who own it. Being a distinct legal entity and abstract in nature, it was not capable of having racial attributes. Therefore the court had no jurisdiction to her the case. Kajubi v Kayanja [1967] 1 EA 301 The respondent, claiming to act under a power of attorney, in his own name sued the appellant in the Buganda Principal Court for “misappropriation of Shs. 8,650/- of the K.B. Coffee Growers Co. Ltd.” By the appellant. It was clear from the proceedings that the real plaintiff was the limited company itself. The appellant objected to the jurisdiction of the Principal Court, but that court, after inspecting the “power of attorney”, and having summoned the members of the limited company before it (presumably to satisfy itself that they were all Africans), gave judgment for the respondent. On appeal the appellant contended that, the jurisdiction of the Principal Court being restricted to disputes between “Africans”, it could not try a case in which a limited liability company was the real plaintiff, such a company not being an “African” within the meaning of the Buganda Courts Ordinance, s. 2. Held The Principal Court had no jurisdiction to entertain a suit by a limited company, which is not an “African” within the meaning of the Buganda Courts Ordinance However, a company is a person for purposes of consent; National and Grindlays Bank & Co v Kentiles & Co [1966] 1 EA 17 The appellant bank advanced money to the respondent company on the security of the company’s land in the highlands. Such a transaction required consent of the relevant authorities but none was obtained. When the company went into liquidation, its liquidator rejected the claim of the bank as Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 15 a secured creditor of the company on the ground that failure to obtained the required consent made the mortgage void. The bank contended that the company was not a person eligible to give consent. Whether a company is a person capable of giving consent? Held – (i) the proper construction of the word “person” in s. 7 of The Land Control Ordinance as amended included a company so that the absence of any consent under that Ordinance and the Crown Lands Ordinance invalidated the purported grant of the legal mortgage; 5. Limited Liability – since a corporation is a separate person from the members, its members are not liable for its debts; In the absence of any provisions to the contrary the members are completely free from any personal liability. In a company limited by shares the members liability is limited to the amount unpaid on the shares whereas in a company limited by guarantee the members liability is limited to the amount they guaranteed to pay. Sentamu v UCB (1983) HCB 59 The plaintiff was managing director of a company and was commissioned by the company to negotiate a loan with the defendant bank. The bank later caused the arrest of the plaintiff in order to recover repayment of the loan. Whether individuals liable for company’s debts. Held A limited liability company is a separate legal entity from its directors, shareholders and other members. Individual members of the company are not liable for the company’s debts. Even as managing director, the plaintiff could not be personally liable for the debts of his company. 6. Suing and Being Sued: As a legal person, a company can take action in it’s own name to enforce its legal rights. Conversely it may be sued for breach of its legal duties. The only restriction on a company’s right to sue is that a lawyer in all its actions must always represent it. Wani v Uganda Timber and Joiners LTD HCCS CS no. 98 of 1972 The plaintiff applied for a warrant of arrest to be issued against the managing director of the defendant company in order that he may be called upon to show cause why he should not furnish security for his company’s appearance at the hearing of the suit where the company was a defendant. This was because, the managing director was Asian and Asians had been expelled from Uganda. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 16 Held; A managing director is not the company and cannot be sued personally. If there is a case against the company, then the company is the right person to be sued not its managing director. In this case, the defendant in the suit was Uganda timbers ltd and not the managing director. 7. Perpetual succession As an artificial person, the company has no body, mind or soul. It has been said that a company is therefore invisible immortal and thus exists only intendment consideration of the law. It can only cease to exist by the same process of law that brought it into existence otherwise; it is not subject to the death of the natural body. Even though the members may come and go, the company continues to exist. 8. Transferability of shares Section 83 of the Companies Act states as follows “ The Shares or any other interests of a member in a company shall be moveable property transferable in the manner provided by the Articles of Association of the Company.” In a company therefore shares are really transferable and upon a transfer the assignee steps into the shoes of the assignor as a member of the company with full rights as a member. Note however that this transferability only relates to public companies and not private companies. The above 8 features or attributes or consequences of corporate personality of a company can be equated to the advantages of having corporate personality and is the reason most people prefer incorporation of a company rather than engage into partnerships. IGNORING THE CORPORATE ENTITY (LIFTING THE VEIL OF INCORPORATION) Although Salomon’s case finally established that a company is a separate and distinct entity from the members, there are circumstances in which these principle of corporate personality is itself disregarded. These situations must however be regarded as exceptions because the Salomon decision still obtains as the general principle Although a company is liable for its own debt which will be the logical consequence of the Salomon rule, the members themselves are held liable which is therefore a departure from principle. The rights of creditors under this section are subject to certain limitations namely (under statutory provision) According to Gower, the concept of separate personality and limited liability does not protect the unpaid workman and the little man and as such the strict application of the doctrine is unfair. The consequences of incorporation are supplemented or curtailed by the principle of lifting the veil of incorporation.the strict application of separate legal personality is ignored in exceptional circumstances and there are rules supplementing or curtailing this doctrine. 1. Son of Loyola FRAUD & IMPROPER CONDUCT Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 17 Where there is fraud or improper conduct, the courts will immediately disregard the corporate entity of the company. Examples are found in those situations in which a company is formed for a fraudulent purpose or to facilitate the evasion of legal obligations. Re Bugle Press Limited [1961] Ch. 270 This was based on Section 210 of the Companies Act where an offer was made to purchase out a company if 90% of shareholders agreed. There were 3 shareholders in the company. A, B and C. A held 45% of the shares, B also held 45% of the shares and C held the remaining 10% of the shares. A and B persuaded C to sell his shares to them but he declined. Consequently A and B formed a new company call it AB Limited, which made an offer to ABC Limited to buy their shares in the old company. A and B accepted the offer, but C refused. A and B sought to use provisions of Section 210 in order to acquire C’s shares compulsorily. The court held that this was a bare faced attempt to evade the fundamental principle of company law which forbids the majority unless the articles provide to expropriate the minority shareholders. Lord Justice Cohen said “the company was nothing but a legal hut. Built round the majority shareholders and the whole scheme was nothing but a hollow shallow.” All the minority shareholder had to do was shout and the walls of Jericho came tumbling down. Gilford Motor Co. v. Horne (1933) Ch. 935 Here the Defendant was a former employee of the plaintiff company and had covenanted not to solicit the plaintiff’s customers. He formed a company to run a competing business. The company did the solicitation. The defendant was not a member nor its director. The defendant argued that he had not breached his agreement with the plaintiffs because the solicitation was undertaken by a company which was a separate legal entity from him. The court held that the defendant’s company was a mere cloak or sham and that it was the defendant himself through this device who was soliciting the plaintiff’s customers. An injunction was granted against the both the defendant and the company not to solicit the plaintiff’s customers. That “the defendant company is a creature of the defendant, a device and a sham, a mask which he holds before his face in an attempt to avoid recognition by the eye of equity.” Jones v. Lipman (1912) 1 W.L.R. 832 This case the Defendant entered into a contract for the sale of some property to the plaintiff. Subsequently he refused to convey the property to the plaintiff and formed a company for the purpose of acquiring that property and actually transferred the property to the company. In an action for specific performance the Defendant argued that he could not convey the property to the Plaintiff as it was already vested in a third party. Justice Russell J. observed as follows “the Defendant company was merely a device and a sham a mask which he holds before his face in an attempt to avoid recognition by the eye of equity” Russell J granted an order for specific performance against both L and A Co to convey the land to J for two reasons both of which amount to lifting the veil, in the accepted sense. First, because Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 18 L, by his absolute ownership and control of A Co, could cause the contract to be completed, the equitable remedy could be granted against him. Secondly, the order could be made against the company because it was a creation of L and ‘a device and a sham, a mask which he holds before his face in an attempt to avoid recognition by the eye of equity’. These two cases show that the courts will refuse to allow a person to hide behind the veil of the company and remain anonymous or deny that they have any connection with the company. Another case where the court would not allow individuals to use a company as cover for improper activities is Re Darby ex p Brougham. (1911) 1 KB 95 Here, D & G, two fraudulent persons whose names were well known in the City, formed a company of which they were the sole directors and controllers. This company acquired a licence to exploit a quarry and then a new company was formed, to which the licence was sold at a grossly inflated sum. The second company’s debentures were then offered for sale to the public and, when the subscription money was received, the debt to the first company was paid. The prospectus issued to the public stated only that the first company was the promoter. It was held that, in reality, D & G were the promoters and, as they received the whole of the fraudulently obtained secret profit, the liquidator of the second company could pursue D & G to account for the profit. The first company was a creature of the defendants meant to avoid the eyes of equity from identifying the directors. 2. THE COMPANY AS AGENT OR NOMINEE Generally there is no reason why a company may not be an agent of its shareholders. The decision in Salomon’s case shows how difficult it is to convince the courts that a company is an agent of its members. In spite of this there have been occasions in which the courts have held that registered companies were not carrying on in their own right but rather were carrying on business as agents of their holding companies. Reference may be made to the case of Smith, Stone and Knight Ltd v Birmingham Corporation [1939] 4 All ER 116, where it was held that the parent company which owned property which was compulsorily acquired by Birmingham Corporation could claim compensation for removal and disturbance, even though it was a subsidiary company which occupied the property and carried on business there. This was because the subsidiary was operating on the property, not on its own behalf, but on behalf of the parent company. After asking a number of questions concerning the degree of control and receipts of profits from the business by the parent company, Atkinson J concluded: if ever one company can be said to be the agent or employee, or tool or simulacrum of another I think the [subsidiary company] was in this case a legal entity, because that is all it was. ... I am satisfied that the business belonged to the claimants, they were ... the real occupiers of the premises. Along similar lines is the decision in Re FG (Films) Ltd, 1953] 1 WLR 483. where Vaisey J held that an English company with no significant assets or employees of its own was merely an agent or nominee for its American parent company. Therefore, any film nominally made in its name Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 19 could not be a ‘British’ film and, therefore, was not entitled to the advantages provided by the Cinematograph Films Acts 1938 The cases on fraud show that there must be a wrongdoer in control of the company using it as a device to facilitate the wrong. Control is both direct (as in Jones v Lipman) and indirect (Gilford’s case). Where there are no controlled shareholders, the veil cannot be lifted because the company is a separate legal entity as the company cannot be identified with the wrong doer. In otherwords, the presence of a genuine third party in a separate legal entity is recognized. However, where the company is set up for purposes of evasion of a transaction in issue, the court may look at the motive behind its incorporation. The focus is on the dishonest use of the company for an evasive purpose. PROMOTERS The Companies Act does not define the term promoter but it is used to describe people involved in setting up the company that is individuals who are involved in the processes of formation up to incorporation excluding those providing professional or administrative services. One of the most well known definition is that of Bowen J, in Whaley Bridge Calico Printing Co v Green,34 where he states that: The term promoter is a term not of law, but of business, usefully summing up in a single word a number of business operations particular to the commercial world by which a company is generally brought into existence. At common law the best definition is that by Chief Justice Cockburn in the case of Twycross – v – Grant (1877) 2C.P.D. 469 Cockburn says “a promoter is one who undertakes to form a company with reference to a given project and to set it going and who takes the necessary steps to accomplish that purpose.” The term is also used to cover any individual undertaking to become a director of a company to be formed. Similarly it covers anyone who negotiates preliminary agreements on behalf of a proposed company. But those who act in a purely professional capacity e.g. advocates will not qualify as promoters because they are simply performing their normal professional duties. But they can also become promoters or find others who will. Whether a person is a promoter or not therefore, is a question of fact. The reason is that Promoter of is not a term of law but of business summing up in a single word the number of business associations familiar to the commercial world by which a company is born. It may therefore be said that the promoters of a company are those responsible for its formation. They decide the scope of its business activities, they negotiate for the purchase of an existing business if necessary, they instruct advocates to prepare the necessary documents, they secure the services of directors, they provide registration fees and they carry out all other duties involved in company formation. They also take responsibility in case of a company in respect of which a Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 20 prospectus is to be issued before incorporation and a report of those whose report must accompany the prospectus. It is important to know whether one is a promoter or not and the point in time he first became a promoter or when he ceased to be a promoter because the law regards a promoter as having certain duties towards a company. DUTIES OF A PROMOTER His duty is to act bona fide towards the company. Though he may not strictly be an agent, or trustee for a company, anyone who can be properly regarded as a promoter stands in a fiduciary relationship vis-à-vis the company. This carries the duties of disclosure and proper accounting particularly a promoter must not make any profit out of promotion without disclosing to the company the nature and extent of such a Promotion. Failure to do so may lead to the recovery of the profits by the company. The question which arises is – Since the company is a separate legal entity from members, how is this disclosure effected? Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphates Co. (1878) 3 A.C. 1218 The promoters of a company sold a lease to the company at twice the price paid for it without disclosing this fact to the company. It was held that the promoters breached their duties and that they should have disclosed this fact to the company’s board of directors. Facts; Frédéric Émile d'Erlanger was a Parisian banker. He bought the lease of the Anguilla island of Sombrero for phosphate mining for £55,000. He then set up the New Sombrero Phosphate Co. Eight days after incorporation, he sold the island to the company for £110,000 through a nominee... The board, which was effectively Erlanger, ratified the sale of the lease. Erlanger, through promotion and advertising, got many members of the public to invest in the company. After eight months, the public investors found out the fact that Erlanger (and his syndicate) had bought the island at half the price the company (now with their money) had paid for it. The New Sombrero Phosphate Co sued for rescission based on non-disclosure, if they gave back the mine and an account of profits, or for the difference. Held; The House of Lords unanimously held that promoters of a company stand in a fiduciary relationship to investors, meaning they have a duty of disclosure. Further, they held, by majority that the contract could be rescinded. As Lord Cairns said Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 21 I do not say that the owner of property may not promote and form a joint stock company, and then sell his property to it, but I do say that if he does, he is bound to take care that he sells it to the company through the medium of a board of directors who can and do exercise an independent and intelligent judgment on the transaction, and who are not left under the belief that the property belongs, not to the promoter, but to some other person. It was clearly stated by James LJ: A promoter is ... in a fiduciary relation to the company which he promotes or causes to come into existence. If that promoter has a property which he desires to sell to the company, it is quite open to him to do so; but upon him, as upon any other person in a fiduciary position, it is incumbent to make full and fair disclosure of his interest and position with respect to that property. Again, in Lagunas Nitrate Co v Lagunas Syndicate[1899] 2 Ch 392., Lindley MR said: The first principle is that in equity the promoters of a company stand in a fiduciary relation to it, and to those persons whom they induce to become shareholders in it, and cannot bind the company by any contract with themselves without fully and fairly disclosing to the company all material facts which the company ought to know Here, the necessary and sufficient disclosure will be to those persons who are invited to become the shareholders. In Salomon v A Salomon and Co Ltd, the lower courts had taken an adverse view of the sale of the business to the company at a gross overvalue by Salomon, who was obviously the promoter, but, in the House of Lords, an argument that the sale of the business to the company should be set aside on Erlanger principles was rejected, since the full circumstances of the sale were known by all the shareholders. So, it appears that there is no duty on a promoter to provide the company with an independent board but disclosure must be to all shareholders. Lagunas Nitrate Co v Lagunas Syndicate Two promoters who were also the only directors, subscribers and shareholders published a prospectus inviting the public to take shares and sold their property to the company. This sale was disclosed in the prospectus indicating that they had interest in the property. It was held that there was no breach of fiduciary duty since there was adequate disclosure hence no rescission. Since the decision in Salomon’s case it has never been doubted that a disclosure to the members themselves will be equally effective. It would appear that disclosure must be made to the company either by making it to an independent Board of Directors or to the existing and potential members. If to the former the promoter’s duty to the company is duly discharged, thereafter, it is upon the directors to disclose to the subscribers and if made to the members, it must appear in the Prospectus and the Articles so that those who become members can have full information regarding it. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 22 It was held in Gluckstein v. Barnes that promoters are bound to disclose all the profits they have accumulated during the promotion of a company and the company may sue the promoters to recover any secret profit that they may have obtained in the course of formation of the company. In this case, Gluckstein and three others bought the Olympia exhibition premises in liquidation proceedings for 140000 and then promoted a company Olympia ltd to which they sold the property for 18,000. There were no independent directors. In a prospectus inviting applications for shares and debentures 40,000 profit was disclosed but not a further 20,000 which they had made by buying securities on the property at a discount and then enforcing them at their face value. The company went into liquidation within four years and the liquidator claimed part of the secret profit. The promoters were liable to refund. It was held that the company should have been informed of what was being done and consulted whether they would have allowed this profit. That the duty to disclose is imposed by the plainest dictates of common honesty as well as by well settled principles of common law. Since a promoter owes his duty to a company, in the event of any non-disclosure, the primary remedy is for the company to bring proceedings for Either rescission of any contract with the promoter or recovery of any profits from the promoter. As regards Rescission, this must be exercised with keeping in normal principles of the contract. 1. the company should not have done anything to ratify the action 2. There must be restitutio in intergram (restore the parties to their original position) The public policy behind restrictions on a promoter is; i. To protect the company from unfair dealings of insiders. ii. To protect innocent third parties like creditors iii. To protect prospective shareholders REMUNERATION OF PROMOTERS A promoter is not entitled to any remuneration for services rendered for the company unless there is a contract so enabling him. In the absence of such a contract, a promoter has no right to even his preliminary expenses or even the refund of the registration fees for the company. He is therefore under the mercy of the Directors. But before a company is formed, it cannot enter into any contract and therefore a promoter has to spend his money with no guarantee that he will be reimbursed. But in practice the articles will usually have provision authorising directors to pay the promoters. Although such provision does not amount to a contract, it nevertheless constitutes adequate authority for directors to pay the promoter. PRE INCORPORATION CONTRACTS These are transactions which are entered into before the company exists and where the company appears to be a party to the contract. It is a contract made before a company’s existence by the promoters. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 23 Until a company is formed, it is legally non-existent and therefore cannot enter into any contract or even do any other acts in law. once incorporated, it cannot be liable on any contract nor can it be entitled under any contract purported to have made on its behalf before incorporation. Ratification is not possible when the ostensible principle is non-existent in law when the contract was entered into. So, prima facie, at common law, a pre-incorporation contract is void and cannot be ratified as ratification requires an existent principle. This principle was established by the case of Kelner v Baxter. Kelner v Baxter 1866 A group of company promoters for a new hotel business entered into a contract, purportedly on behalf of the company which was not yet registered, to purchase wine. Once the company was registered, it ratified the contract. However, the wine was consumed before the money was paid, and the company unfortunately went into liquidation. The promoters were sued. They argued that their liability had passed to the company, and were not personally accountable. Held; A pre-incorporation contract is void ab initio and can’t be ratified. Ratification presupposes an existent principle having capacity to contract at the time the contract was entered into. That whoever professes to act on behalf of a nonexistent principle may be held personally liable. Erle CJ ; where a contract is signed by one who professes to be signing “as agent,” but who has no principal existing at the time, and the contract would be altogether inoperative unless binding upon the person who signed it, he is bound thereby: and a stranger cannot by a subsequent ratification relieve him from that responsibility. When the company came afterwards into existence it was a totally new creature, having rights and obligations from that time, but no rights or obligations by reason of anything which might have been done before. Byles J; the true rule, however, is that persons who contract as agents are generally personally responsible where there is no other person responsible as principal. This case was considered and distinguished in Newborne v Sensolid (Great Britain) Ltd [1954] 1 QB 45 The plaintiff was the promoter and prospective director of a limited company, Leopold Newborne (London) Ltd, which at the material time had not been registered. A contract for the supply of goods to the defendants was signed: “Leopold Newborne (London), Ltd” and the plaintiff’s name, “Leopold Newborne”, was written underneath. In an action for breach of the contract brought by the plaintiff against the defendants, Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 24 Held – The contract was made, not with the plaintiff, whether as agent or as principal, but with a limited company which at the date of the making of the contract was non-existent, and, therefore, it was a nullity and the plaintiff could not adopt it or sue on it as his contract. Per Lord Goddard CJ; It seems to me a very long way from saying that every time a prospective company, not yet in existence, purports to contract everybody who signs for the company makes himself personally liable This contract purports to be made by the company, not by Mr Newborne. He purports to be selling, not his goods, but the company’s goods. The only person who has any contract here is the company, and Mr Newborne’s signature is merely confirming the company’s signature. The document is signed: “Yours faithfully, Leopold Newborne (London), Ltd”, and the signature underneath is that of the person authorised to sign on behalf of the company In this case in rejecting Kelner v Baxter, court looked at the way in which the contract was signed, it was the company which purported to make the contract and the promoter did not sign as agent or on behalf of the company but only to authenticate the signature of the company. Remember in Klener v Baxter, the promoters signed as “on behalf of the company” However, Newbornes case still strengthened the position in Kelner that a pre-incorporation contract cannot be enforced against the company. The above case of Newborne was applied in Black v Smallwood. In this case, Black and others contracted to sell land to the company known as Western Suburbs Holdings and the agreement was signed by the defendants Robert Small and J Cooper as the directors. The two signed as directors in the mistaken belief that the company had been incorporated. Court applied Newbornes case and held that Kelner v Baxter, is not an authority for the principle that an agent signing for a non-existent principle is bound. That if a pre-incorporated contract objectively has an intention to bind the company only then the promoter does not necessarily take the liability especially if the promoter had not known the fact that the company had not been incorporated. The two cases then modify the rule in Kelner on liability of a promoter on a preincorporation to this; whoever professes to act as an agent of a non existent company is personally liable on the contract, but this depends on the intention of the promoter at the time of signing. However, all the three cases support the proposition that a pre-incorporation contract is void and unenforceable. The question then is how can a company be bound by a pre-incorporation contract? The only way a company can be bound is to make a new contract between the company after incorporation and the parties concerned. This is what is called in law a novation. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 25 It was held in Motani v Thobani (1945) 2 EACA 37 that a sale agreement made before the company was incorporated was not binding on it and could not subsequently be ratified by the company. The company could only be liable if there were a new contract to which it was a party. The question of whether there is a new contract, is a question of fact depending on each case. Price v. Kelsall (1957) E.A. 752 One of the issues in this case was whether or not a company could ratify a contract entered into on its behalf before incorporation. The alleged contract was that the Respondent had undertaken to sell some property to a company which was proposed to be formed between him and the Appellant. In holding that a company cannot ratify such an agreement, the Eastern Africa Court of Appeal as then constituted O’Connor President said as follows; A company cannot ratify a contract purporting to be made by someone on its behalf before its incorporation but there may be circumstances from which it may be inferred that the company after its incorporation has made a new contract to the effect of the old agreement. The mere confirmation and adoption by Directors of a contract made before the formation of the company by persons purporting to act on behalf of the company creates no contractual relations whatsoever between the company and the other party to the contract.” Re Northumberland Avenue Hotel Co Ltd (1886),. A contract was made between W. and D., as the agent for an intended company, for the assignment of a lease. The company, on its formation, entered on the land the subject of the lease and erected buildings on it, but did not make any fresh agreement with respect to the lease. Held, the agreement being made before the formation of the company, was not binding on the company, and the acts of the company were not evidence of a fresh agreement between W. and the company. Even if the company takes the benefit of a contract made before its incorporation, the contract is not binding on the company. Justice Lopez; when the company came into existence, it could not ratify that contract because the company was not in existence at the time the contract was made. That the company might have entered into a new contract upon the same terms as the agreement and this should not be inferred from the conduct and the transactions of the company when it came into existence. In Howard v Patent Ivory Manufacturing Co (1888) 38 Ch 156 the court noted that it has to be a fresh agreement even if its on the same terms. . The above common law position in Baxter and the subsequent cases has been modified further by S. 54 of the Companies Act 2012 which provides that; (1) A contract which purports to be made on behalf of a company before the company is formed, has effect, as one made with the person purporting to act for the company. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 26 (2) A company may adopt a pre-incorporation contract with its formation and registration made on its behalf without a need for novation. (3) In all cases where the company adopts a pre-incorporation contract, the liability of the promoter of that company shall cease. The effect of the above section is that, a pre-incorporation contract is no longer void but voidable as it can be adopted by the company without a need for a novation. However, the section stresses that a promoter is personally liable on the pre-incorporation contract no matter how he signs it unless the company adopts the contract and thereby his liability ceases. The interpretation of this section was given by Lord Denning in Phonogram Ltd v Lane (1981)3 ALL ER 182. Where he stated that; The section means that in all cases where a person purports to contract on behalf of the company not yet formed, then, however he expresses his signature, he himself is personally liable on the contract. That there has to be clear exclusion of personal liability and this cannot be made by inferences from the way in which the contract was signed. This section does not overrule the common law position, which is still good law where the company fails to adopt the contract. ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION A Company’s constitution is composed of two documents namely the Memorandum of Association and the Articles of Association. The Articles of Association are the more important of the two documents in as much as most court cases in Company Law deal with the interpretation of the Articles. S.11 states that It shall be lawful for a company to register in addition to its memorandum and articles of association, such regulations of the company as the company may deem necessary. However, Section 12 of the Companies Act provides that a Company limited by guarantee or an unlimited company must register with a Memorandum of Association, Articles of Association describing regulations for the company. A company limited by shares may or may not register articles of Association. A Company’s Articles of Association may adopt any of the provisions which are set out in Schedule 1 Table A of the Companies Act 2012. Ref S.13 (1) Articles of association may adopt all or any of the regulations contained in Table A. (2) In the case of a company limited by shares and registered after the commencement of this Act, if articles are not registered or, if articles are registered in so far as the articles do not exclude or modify the regulations contained in Table A, those regulations shall, so far as applicable, be the regulations of the company in the same manner and to the same extent as if they were contained in the duly registered articles. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 27 Table A is the model form of Articles of Association of a Company Limited by Shares. It is divided into two parts designed for public companies in part A and for private companies in part B (II) thus a company has three options. It may either i. ii. iii. Adopt Table A in full; or Adopt Table A subject to modification or Register its own set of Articles and thereby exclude Table A altogether. In the case of a company limited by shares, if no articles are registered or if articles are registered insofar as they do not modify or exclude Table A the regulations in Table A automatically become the Company’s Articles of Association. Section 15 of the Companies Act requires that the Articles must be in the English language printed, divided into paragraphs numbered consecutively dated and signed by each subscriber to the Memorandum of Association in the presence of at least one attesting witness. As between the Memorandum and the Articles, the Memorandum of Association is the dominant instrument so that if there is any conflict between the provisions in the Memorandum and those in the Articles the Memorandum provisions prevail. However if there is any ambiguity in the Memorandum one may always refer to the Articles for clarification but this does not apply to those provisions which the Companies Act requires to be set out in the Memorandum as for instance the Objects of the Company. The relationship between the memorandum of association and Articles of association was given by Lord Bowen In Guinness v land Corporation of Ireland (1882) Ch D 349 There is an essential difference between the memorandum and articles. The memorandum contains the fundamental conditions upon which alone the company is allowed to be incorporated. They are conditions introduced for the benefit of the creditors, and the outside public as well as the shareholders. The Articles of association are the internal regulations of the company. They cannot be said to be construed together. That is the fundamental conditions of the charter of incorporation and the internal regulations of the company cannot be construed together. It is certain that for anything which the Act of parliament says shall be in the memorandum, you must look to the memorandum alone. If the legislature has said that one instrument is to be dominant, you cannot turn to another instrument and read it in order to modify the provisions of the dominant instrument. The memorandum prevails over the articles. Whereas the Memorandum confers powers for the company, the Articles determine how such powers should be exercised. Articles regulate the manner in which the Company’s affairs are to be managed. They deal with inter alia the issue of shares, the alteration of share capital, general meetings, voting rights, appointment of directors, powers of directors, payment of dividends, accounts, winding up etc. They further provide a dividing line between the powers of share holders and those of the directors. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 28 LEGAL EFFECTS OF THE ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION An issue which has caused a considerable amount of litigation and much discussion among commentators is the extent to which the terms of the company’s constitution can be enforced both by the company and its members. The starting point is S. 21,Companies Act 2012 which states as follows: Subject to this Act, the memorandum and articles shall, when registered, bind the company and the members of the company to the same extent as if they had been signed and sealed by each member and contained covenants on the part of each member to observe all the provisions of the memorandum and articles. This has the effect of establishing the memorandum and articles as a ‘statutory contract’ between the company and its members, and among members inter se the terms of which can be enforced both by the company and the members Reference may be made to the case of Hickman v. Kent (1950) 1 Ch. D 881 Here the Articles of the Company provided that any dispute between any member and the company should be referred to arbitration. A dispute arose between Hickman and the company and instead of referring the same to arbitration, he filed an action against the company in the High Court. The company applied for the action to be stayed pending reference to arbitration in accordance with the company’s articles of association. The court held that the company was entitled to have the action stayed since the articles amount to a contract between the company and the Plaintiff one of the terms of which was to refer such matters to arbitration. Justice Ashbury had the following to say: “That the law was clear and could be reduced to 3 propositions; i. That no Article can constitute a contract between the company and a third party; ii. No right merely purporting to be conferred by an article to any person whether a member or not in a capacity other than that of a member for example solicitor, promoter or director can be enforced against the company. iii. Articles regulating the rights and obligations of the members generally as such do create rights and obligations between members and the company”. Ashbury thus held that; general articles dealing with the rights of members as such should be treated as a statutory agreement between them and the company as well as between the members interse. From this case, therefore, the effect of the articles of association creates a statutory contract derived from S. 21 itself and the law cannot say that there is a contract and you say otherwise. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 29 The contract which s 14 creates, however, is and remains a special statutory contract, with its own distinctive features. The contract derives its force from the statute and not from any bargain struck between the parties and, therefore, it is subject to other provisions of the Act. Section 16 for instance, provides that the articles, the terms of the statutory contract, can be altered by a special resolution of the members voting in general meeting, in contrast to the case of a ‘normal contract’, where unanimity between the parties would be required for a variation of contractual terms. Enforcement of the articles; Under S. 21 The articles create a statutory contract binding the company and the members and the members inter se. This means that the articles can be enforced by both the company and members. In Hickman v Kent, the company successfully enforced the articles against a member who had referred the dispute to the high court yet the articles required the dispute to be before an arbitration. The articles can also be enforced by a member against a company and against another member. This is shown by the case of; Wood v. Odessa Waterworks Company [1880] 42 Ch. 636 The articles empowered the directors with the sanction of a general meeting to declare a dividend to be paid to the shareholders. The company passed an ordinary resolution proposing to pay no dividends but instead to give the shareholders debentures. Wood, a shareholder sought an injunction to restrain the company from acting on that resolution. Held; That the proposal was inconsistent with the articles of association and the injunction was granted. Sterling J. had the following to say: “the articles of association constitutes a contract not merely between shareholders and the company but also between each individual shareholders and every other.” This case shows that any member has the right to enforce the observance of the terms of the articles. This case was followed in Rayfield v. Hands (1960) Ch.d 1 Rayfield v. Hands (1960) Ch.d 1 (1958)2 ALL ER 1941 Here the company’s articles provided that every member who intends to transfer his shares shall inform the directors who will take those shares between them equally at a fair value. The Plaintiff called upon the directors to take his shares but they refused. The issue was whether the articles gave rise to a contract between the Plaintiff and the directors. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 30 The court here held that the Articles related to the relationship between the Plaintiff as a member and the Defendants not as directors but as members of the company. Therefore the Defendants were bound to buy the Plaintiff shares in accordance with the relevant article. The plaintiff was not obliged to join the company as a party. The principle in this case therefore is that one member can enforce the articles against another member without joining the company as a party. Salmon v Quin Axtens Ltd 91909) 1 Ch 311 (1909) AC 442 The claimant Salmon had been one of the two managing directors (as well as a member) of the company, the constitution of which provided that the company’s managing directors had the power to veto certain resolutions of its board of directors. Salmon duly exercised his right to veto such a resolution. However, the company purported to carry it out anyway. Accordingly Salmon sought an injunction to prevent the company from acting in breach of its constitution. Held; That Salmon as a member of the company was entitled to require the company to abide by its articles. The effect of allowing the board to continue would have been to remove the power of veto which could only be done using a special resolution. Membership or outsider rights for enforcement. It must be noted that for a member to enforce the terms of the articles, he oshe must be acting in his capacity as a member. Even if one is a member but seeks to rely on the articles in another capacity either as director, solicitor of the company, his action will fail. Lord Ashbury stated the position in Hickman v Kent that An outsider to whom rights purport to be given by the articles in his capacity as such outsider, whether he is or subsequently becomes a member, cannot sue on those articles treating them as contracts between himself and the company to enforce those rights. He thus held that; i. ii. That no Article can constitute a contract between the company and a third party; No right merely purporting to be conferred by an article to any person whether a member or not in a capacity other than that of a member for example solicitor, promoter or director can be enforced against the company. This can be explained by the following cases. Eley v. Positive Government Security Life Association Co. (1876) Ex 88 Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 31 In this case, the company’s articles provided that Eley should become the company Solicitor and should transact all legal affairs of the company for mutual fees and charges. He bought shares in the company and thereupon became a member and continued to act as the company’s solicitor for some time. Ultimately the company ceased to employ him. He filed an action against the company alleging breach of contract. The court held: that the articles constitute a contract between the company and the members in their capacity as members and as a solicitor Eley was therefore a third party to the contract and could not enforce it. The contract relates to members in their capacity as members and the company so its only a contract between the company and members of that company and not in any other capacity such as solicitor. This view was applied in ; Beattie v Beattie (1938) CH 708 (1938) 3 ALL ER 214 A dispute arose between a company and one of its directors, concerning an alleged breach of a duty by the director. There was a clause in the company’s articles obliging all disputes between the company and a member to be referred to arbitration. The appellant director, who was also a member, sought to rely on this clause to avoid the dispute being aired in court. Held; A member seeking to enforce the constitution must be acting in his capacity as a member. Constitution provisions that do not relate to membership rights will not normally form part of the statutory contract. The claim failed because this was a dispute between the company and the appellant in his capacity as director. As director and a disputant in this action, he had no right to enforce the terms of the article. The first cases succeeded because, the action was being brought by a person in his capacity as a member. Outsider rights are therefore unenforceable under the articles. ALTERATION OF ARTICLES The articles of association, being a statutory contract can only be altered subject to the Act. any provision forbidding amendment of the articles is null and void because the Act provides for amendment. Section 16 of the Companies Act gives the company power to alter the articles by special resolution. This is a statutory power and a company cannot deprive itself of its exercise. Reference may be made to the case of Andrews v. Gas Meter Co. (1897) 1 Ch. 361 The issue herein was whether a company which under its Memorandum and Articles had no power to issue preference shares could alter its articles so as to authorise the issue of preference shares by way of increased capital Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 32 The court held that as long as the Constitution of a Company depends on the articles, it is clearly alterable by special resolution under the powers conferred by the Act. Therefore it was proper for the company to alter those articles and issue preference shares. Any regulation or article which purports to deprive the company of this power is therefore invalid, on the ground that such an article or regulation will be contrary to the statute. The only limitation on a company’s power to alter articles is that the alteration must be made in good faith and for the benefit of the company as a whole. Allen v. Gold Reefs of West Africa (1900) 1 Ch. 626 In this case the company had a lien on all debts by members who had not truly paid up for their shares. Mr. Zuccani held some partly paid up shares and also owned the only fully paid up shares issued by the company. The Articles were altered to extend the Company’s lien to those shares which were fully paid up. held That since the power to alter the Articles is statutory, the extension of the lien to fully paid up shares was valid. So long as the resolution was done bonafide for the benefit of the company as a whole, restrictions on the freedom of a company to alter its articles are invalid. These were the words of Lindley L.J. “Wide however as the language of Section 13 ( ours is 16) mainly the power conferred by it must be exercised subject to the general principles of law and equity which are applicable to all powers conferred on majorities and enabling them to bind minorities. It must be exercised not only in the manner required by law but also bona fide for the benefit of the company as a whole.” Further reference may be made to the case of Shuttleworth v. Cox Brothers Ltd (1927) 2 KB29 Here the Articles of the Company provided that the Plaintiff and 4 others should be the first directors of the company. Further each one of them should hold office for life unless he should be disqualified on any one of some six specified grounds, bankruptcy, insanity etc. The Plaintiff failed to account to the company for certain money he had received on its behalf. Under a general meeting of the company a special resolution was passed that the articles be altered by adding a seventh ground for disqualification of a director which was a request in writing by his co-directors that he should resign. Such request was duly given to the Plaintiff and there was no evidence of bad faith on the part of shareholders in altering the articles. The Plaintiff sued the company for breach of an alleged contract contained in their original articles that he should be a permanent director and for a declaration that he was still a director. The court held that the contract if any between the Plaintiff and the company contained in the original articles in their original form was subject to the statutory power of alteration and if the Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 33 alteration was bona fide for the benefit of the company, it was valid and there was no breach of contract. Lord Justice Bankes observed as follows “In this case, the contract derives its force and effect from the Articles themselves which may be altered. It is not an absolute contract but only a conditional contract.” The question here is who determines what is for the benefit of the company? Is it the shareholders or the Courts? Scrutton L.J. had the following to say “to adopt such a view that a court should decide will be to make the court the manager of the affairs of innumerable companies instead of shareholders themselves. It is not the business of the court to manage the affairs of the company. That is for the shareholders and the directors.” Brown v. British Abrasive Wheel Co. (1990) 1 Ch. 290 Here a public company was in urgent need of further capital which the majority of the members who held 98% of the shares were willing to supply if they could buy out the minority. They tried persuasion of the minority to sell shares to them but the minority refused. They therefore proposed to pass a Special Resolution adding to the Articles a clause whereby any shareholder was bound to transfer his shares upon a request in writing of the holders of 98% of the issued capital. held The court held that this was an attempt to add a clause which will enable the majority to expropriate the shares of the minority who had bought them when there was no such power. Such an attempt was not for the benefit of the company as a whole but for the majority. An injunction was therefore granted to restrain the company from passing the proposed resolution. One reason for this was that there was no direct link between the provisions of extra capital and the alteration of the articles. Although the whole scheme had been to provide the capital after removing the dissenting shareholders, it would in fact have been possible to remove the shareholders and then refuse to provide the capital. Sidebottom v. Kershaw Leese & C0.[1920]1 Ch. 154 A company had a minority shareholder who was interested in some competing business. The company passed a special resolution empowering the directors to require any shareholder who competed with the company to transfer his shares at their fair value to nominees of the directors. The Plaintiff was duly served with such a notice to transfer his shares. He thereupon filed an action against the company challenging the validity of that article. He argued that a previous case of Brown v British abrasive, where a change for compulsory share purchase was held invalid as not being bonafide for the beneft of the company as a whole should be applied here too. Held; The court held that the company had a power to re-introduce into its articles anything that could have been validly included in the original articles provided the alteration was made in good faith and for the benefit of the company as a whole and since the members considered it beneficial to the company to get rid of competitors, the alteration was valid. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 34 That the alteration was for the best interests of the company as the minority shareholder by competing with the company could damage the company. Lord Stendale Mr. The whole of this case comes down to rather a narrow question of fact, which is this; when the directors of this company introduced this alteration giving powers to buy up the shares of the members who were in competing business, did they do it bonafide for the benefit of the company or not? It seems to me quite clear that it may be very much to the benefit of the company to get rid of members who are in competing business.” Dafen Tinplate Co Ltd v Llanelly Steel Co (1920) 2 Ch 124 D was a shareholder in the L company. The company realized that D was buying steel from an alternative source of supply and also attempted to buy up the company’s shares. L responded by altering its articles through a special resolution to include the power to compulsorily purchase the shares of any member requested to transfer them. D argued that the alteration was invalid. Held; That the alteration was too wide to be valid. The altered article would confer too much power on the majority. It went much further than was necessary for the protection of the company. The judge applied the bonafide for the benefit of the company test in an objective sense, Peterson J interpreted the Allen v Gold Reefs test as being “whether in fact the alteration is genuinely for the benefit of the company” and in holding that this was not, stated; It may be for the benefit of the majority of the shareholders to acquire the shares of the minority, but how can it be said to be for the benefit of the company that any shareholder against whom no charge of acting to the detriment of the company can be urged and who is in every respect a desirable member of the company and for whose expropriation there is no reason except the will of the majority should be enforced to transfer his shares to the majority or anyone else? it has been stated by writers that the case of Sidebottom applied a subjective clause while that of Dafen applied an objective clause. In Peters American delicacy Co ltd v Heath (1936) 61 CLR 457, it was held that; An alteration of articles which discriminates against holders of partly-paid up shares in favor of the majority shareholders did not constitute a fraud on the minority in the circumstances. Such alteration must be valid unless the party complaining can establish that the resolution was passed fraudulently or oppressively or was so extravagant that no reasonable person could believe that it was for the benefit of the company. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 35 Characteristics of the contract created by the articles of association. As already stated, the nature of the contract is statutory and hence is distinct from the ordinary contract. The contract which S.21 creates, however, is and remains a special statutory contract, with its own distinctive features. The contract derives its force from the statute and not from any bargain struck between the parties and, therefore, it is subject to other provisions of the Act It therefore has the following characteristics. i. ii. iii. iv. It is a statutory contract which derives its force from the statute and not from any bargain struck between the parties. The contract can be altered by a special resolution. This is in contracts to the case of a normal contract where unanimity between the parties would be required for a variation of contractual terms. Unlike an ordinary contract, a statutory contract is not defeasible on the grounds of misrepresentation, common law mistake, undue influence or duress. All these relate to consent but by subscribing to the articles, the party will have consented and the company is an artificial person conducting its business through individuals, so the question of vitiating factors does not arise. The court has no jurisdiction to rectify the articles once registered even if it could be shown that they did not as they presently stood, represent what was the true original intentions of the persons who formed the company. This is because, the articles are registered. Scott v Frank Scott (London) Ltd (1940) CH 794 The issue was whether the defendant was entitled to have the articles of association rectified in the manner claimed by them. Bennet J at first said that he was prepared to hold that the articles of association as registered were not in accordance with the intention of the three brothers who were the only signatories and shareholders. He however held that; The court has no jurisdiction to rectify the articles of association of a company although they do not accord with what is proven to have been the cocurrent intention of all the signatories there in at the moment of signature. The court of appeal unanimously confirmed this view holding that; There is no room in the case of a company incorporated under the appropriate statute or statutes for the application to either memorandum or articles of association of the principles upon which a court of equity permits rectification of documents whether interpartes or not. v. The articles cannot be supplemented by additional terms implied from extrinsic circumstances. Bratton Seymour Service Co Ltd v Oxborough (1992) 3 CLC 693 Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 36 The company was set up to manage the commercial aspects of a development consisting of a number of flats, the shares being held by the flat owners. The question for the court was whether it was possible to imply into the company’s articles a term that the shareholders should make contributions for the upkeep of the garden, swimming pool and other communal amenity areas if the development. Held; The court of appeal held that no such term could be implied. Neither can the company nor any member seek to add to or to subtract from the terms of the articles by way of implying a term derived from extrinsic surrounding circumstances. Permitting such would be prejudicial to third parties, namely potential shareholders who are entitled to look and rely on the articles of association as registered. (public policy); An implication should only be derived from the language of the articles but not purely from extrinsic circumstances. The characteristics of the statutory contract created by articles of association, its enforcement and effect, were stated by Steyn LJ; in the above case of Bratton Seymour Service Co Ltd v Oxborough (1992) 3 CLC 693 as follows; The law provides that the memorandum and articles of association when registered bind the company and its members to the same extent as if they respectively had been signed and sealed by each member. By virtue of the section, the articles of association become upon registration a contract between the company and the members. It is however, a statutory contract of a special nature with its own distinctive features. It derives its binding force not from a bargain struck between parties but from the terms of the statute. It is binding only in so far as it affects the rights and obligations between the company and the members acting in their capacity as members. If it contains provisions conferring rights and obligations on outsiders, then these provisions do not bite as part of the contract between the company and the members even if the outsider is coincidentally a member. The contract can be altered by a special resolution without the consent of all the contracting parties. It is also unlike an ordinary contract, not defeasible on the grounds of misrepresentation, common law mistake, undue influence or duress. Neither can the company nor any member seek to add to or to subtract from the terms of the articles by way of implying a term derived from extrinsic surrounding circumstances. THE DOCTRINE OF ULTRA VIRES A Company which is registered under the Company’s Act cannot effectively do anything beyond the powers which are either expressly or by implication conferred upon in its Memorandum of Association. Any purported activity in excess of those powers will be ineffective even if agreed to by the members unanimously. This is the doctrine of ultra vires in company law. The purpose of this doctrine is said to be twofold Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 37 It is said to be intended for the protection of the investors who thereby know the objects in which their money is to be applied. It is also said to be intended for the protection of the creditors by ensuring that the Company’s assets to which the creditors look for repayment of their debt are not wasted in unauthorised activities. The doctrine was first clearly articulated in 1875 in the case of Ashbury Railway Carriage v. Riche (1875) L.R. CH.L.) 653 In this case the Company’s Memorandum of Association gave it powers in its objects clause To make sell or lend on hire railway carriages and wagons, to carry on the business of mechanical engineers and general contractors, to purchase, lease work and sell mines, minerals, land and realty. The directors entered into a contract to purchase a concession for constructing a railway in Belgium. The issue was whether this contract was valid and if not whether it could be ratified by the shareholders. The House of Lords held that the contract was ultra vires the company and void so that not even the subsequent consent of the whole body of shareholders could ratify it. Lord Cairns stated as follows: This contract was entirely beyond the objects in the Memorandum of Association. If so, it was thereby placed beyond the powers of the company to make the contract. If so, it was not a question whether the contract was ever ratified or not ratified. If the contract was void at its beginning it was void because the company could not make it and by purporting to ratify it the shareholders were attempting to do the very thing which by the Act of parliament they were prohibited from doing. It was the intention of the legislature not implied but actually expressed that the corporations should not enter, having regard to the memorandum of association, into a contract of this description. The contract could not have been ratified by the unanimous assent of the whole corporation. It is necessary to state that nothing shall be done beyond that ambit and that no attempt shall be made to use the corporate life for any other purpose than that which is so specified. The ultra vires rule from this case therefore is this; that any matter that is not expressly provided for in the memorandum of association is ultra vires; that any contract entered into outside the terms of the objects clause was ultra vires and, therefore, void. Further, the contract could not be ratified by the consent of the shareholders. The clear view of their Lordships was that the rule existed for the protection of both the shareholders, both present and future, and the persons who might become creditors of the company Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 38 The courts construed the object clause very strictly and failed to give any regard to that part of the Objects clause which empowered the company to do business as general contractors. This construction gave the doctrine of ultra vires a rigidity which the times have not been able to uphold. The harshness of the rule was seen in; Re Jon Beauforte [1953] Ch 131. Here, a company had been incorporated with an objects clause which authorised the company to carry on business as makers of ladies’ clothes, hats and shoes. The company later decided to manufacture veneered panels. To further this latter business, the company contracted with a builder to construct a factory, entered into a contract with a supplier of veneer and ordered coke from a coke supplier to heat the factory. All three remained unpaid when the company went into liquidation and the liquidator rejected their proofs in the winding up on the ground that the contracts were to further an ultra vires activity and were, therefore, void. These rejections were upheld by Roxburgh J. The rejection of the coke supplier’s proof was particularly harsh, since, whereas the builder conceded that the contract was ultra vires, the coke supplier was unaware of the purpose for which the coke would be used and it could easily have been used to further legitimate objects. However if a contract was void for being ultra vires, then notice on the part of the third party, whether actual or constructive was irrelevant to the result At the present day, the doctrine is not as rigid as in Ashbury’s case and consequently it has been eroded. The first inroad into the doctrine was made five years later in the case of ; Attorney General V. Great Eastern Railway 1880) 5 A.C. 473 An Act of parliament authorized a company to construct a railway. Two other companies combined and contracted with the first to supply rolling stock. An injunction was brought to restrain this, saying that such a contract was not explicitly provided for in any of the Acts incorporating the companies. Held; The contract was not ultra vires, but was warranted by the Acts. Powers conferred by statute are taken to include, by implication, a right to take any steps which are reasonably necessary to achieve the statutory purpose. The court should not hold as ultra vires whatever may fairly be regarded as incidental to or consequential upon those things which the legislature has authorized. Lord Selbourne stated as follows: “the doctrine of ultra vires ought to be reasonably and not unreasonably understood and applied and whatever may fairly be regarded as incidental to or consequential upon those things that the legislature has authorised ought not to be held by judicial construction to be ultra vires.” Lord Blackburn said: ‘ Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 39 where there is an act of Parliament creating a corporation for a particular purpose, and giving it powers for that particular purpose, what it does not expressly or impliedly authorise is to be taken to be prohibited’ and ‘those things that are incident to, and may reasonably and properly be done under the main purpose, though they may not be literally within it, would not be prohibited An act of the company therefore will be regarded as intra vires not only when it is expressly stated in the object’s clause but also when it can be interpreted as reasonably incidental to the specified objects. As a result of this decision, there is now a considerable body of case law deciding what powers will be implied in a case of particular types of enterprise and what activities will be regarded as reasonably incidental to the act. In Re David Payne and Co Limited (1904) Ch 608 David Payne and Co’s memorandum of association contained a clause to borrow and raise money for the purposes of the company’s business and there was a clause in the articles of association which gave power to the directors to borrow or raise or secure any sums of money on the security of the property of the company by issue of debentures. The directors of the company wanted to borrow money to be used for a different purpose other than the company’s business. K one of the directors of Exploring Land and Minerals Co attended a meeting where such a decision was taken and was asked to convince his company to lend money to Payne. K then convinced the company’s director to advance the money which were lent to Payne on issue of debentures. However, K did not disclose to his company that the money was intended for a different purpose than was borrowed. In winding up Payne Co. the liquidator challenged the debentures on grounds that the borrowing was not authorized by the memorandum and articles of association of the company and was ultra vires and that K’s knowledge ought to be imputed on the lending company. Held; Where a company has a general power, to borrow money for the purposes of its business, a lender is not bound to inquire into the purposes for which the money is intended to be applied and the misapplication of the money by the company does not avoid the loan in the absence of knowledge on the part of the lender that the money was intended to be misapplied. K’s knowledge ought not to be imputed to the lending company in as much as K owed no duty to that company either to receive or to disclose information as to how the borrowed money was to be applied and that the debenture was a valid security. In this case, the court was not prepared to construe the words ‘for the purpose of the company’s business” as limiting the corporate capacity but construed them as limiting the authority of directors. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 40 ‘Cotman’ Clauses/ independent objects clause. Companies responded to the ultra vires doctrine with the development of what came to be called ‘independent objects’ or ‘Cotman’ clauses. by drafting very wide and lengthy objects clauses which attempted to include every conceivable form of commercial activity. This was the device of inserting a clause at the end of the memorandum specifying that each objects clause was to be construed as a separate and independent object and that clauses were expressly stated as not to be treated as ancillary to each other. The technique is called ‘cotman’ because it was established in Cotman v Broughma. Cotman v Brougham (1918) AC 514 A rubber company had an object clause with thirty sub clauses enabling it to carry on almost every kind of business. The first sub clause authorized the company to develop rubber plantations and sub clause 12 allowed the company to promote companies and deal in shares of other companies. The company underwrote and had allotted to it shares in an oil company. The final clause of the objects clause said in effect that each sub-clause should be considered as an independent main clause and not subsidiary to another. When the oil company was wound up, the rubber company was placed on the list of contributories and it asked to be removed from the list because the contract was ultra vires and void. The House of Lords unanimously held; That the effect of the independent objects clause was to constitute each of the 30 objects of the company as independent objects. That the transaction was indeed within the capacity of the company. Although the House of Lords disapproved strongly of the independent objects clause, the fact that the Registrar of Companies had granted a certificate of incorporation based on the memorandum was held to conclusively bind the court. Nevertheless, the practice was described as ‘pernicious’ by Lord Wrenbury and Lord Finlay LC was of the view that the relevant Act, the Companies (Clauses) Consolidation Act 1908 (UK), should be amended to prevent what the court saw as an abuse of the legislation. In an instructive passage outlining the struggle between the draftsmen and the court, Lord Wrenbury stated: There has grown up a pernicious practice of requiring memoranda of association which under the clause relating to objects contain paragraph after paragraph not delimiting or specifying the proposed trade or purpose, but confusing power with purpose and indicating every class of act which the corporation is to have power to do. The practice is not one of recent growth. It was in active operation when I was a junior at the Bar. After a vain struggle I had to yield to it, contrary to my own convictions. It has arrived now at a point at which the fact is that the function of the memorandum is taken to be, not to specify, not Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 41 to disclose, but to bury beneath a mass of words the real object or objects of the company, with the intent that every conceivable form of activity shall be found included somewhere within its terms. The present is the very worst case of the kind that I have seen. Lord Parker of Waddington gave the public policy behind the memorandum of association. : “The truth is that the statement of a company’s objects in its memorandum is intended to serve a double purpose. In the first place, it gives protection to subscribers, who learn from it the purposes to which their money can be applied. In the second place, it gives protection to persons who deal with the company, and who can infer from it the extent of the company’s powers. The narrower the objects expressed in the memorandum the less is the subscribers’ risk, but the wider such objects the greater is the security of those who transact business with the company Subjective objects clause. Eventually, the Court of Appeal was even prepared to give effect to a clause which provided that the company could ‘carry on any other trade or business whatsoever which can, in the opinion of the board of directors, be advantageously carried on by the company in connection with or as ancillary to any of the above businesses or the general business of the company’ and held that a particular transaction was intra vires even though it had no objective connection with a relationship to the company’s main business. Bellhouse v. City Wall Properties (1966) 2 Q.B 656 The company’s objects as set up in the Memorandum of Association contained the Clause authorising the company to “carry on any other trade or business whatsoever which can in the opinion of the Board of Directors be advantageously carried on by the company in connection with or as ancillary to any of the above businesses or a general business of the company”. In connection with its various development skills the company’s managing director met an agent of the Defendants who required some finance to the tune of about 1 million pounds. The Plaintiff’s Managing Director intimated to the Defendant’s agent that he knew of a source from which the Defendant could obtain finance and accordingly referred them to a Swiss syndicate of financiers. Which had earlier contacted the plaintiff company to finance any of their projects but the plaintiff company had nothing planned at the moment. The defendants promised to pay the plaintiff company a commission of 20,000 pounds and after getting the money the defendant company refused to pay the commission and was used for breach of contract. The Defendants argued that there was no contract between the parties. In the alternative they argued that even if there was a contract such contract was in effect one whereby the Plaintiffs undertook to act as money-brokers which activity was beyond the objects of the plaintiff company and which was therefore ultra vires. The issues was whether the contracts were ultra vires Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 42 The court of first instance decided that the contract was ultra vires and it was open to the defendant to raise the defence of ultra vires. However a unanimous court of appeal reversed the decision and held that the words stated must be given their natural meaning and the natural meaning of those words was such that the company could carry on any business in connection with or ancillary to its main business provided that the directors thought that could be advantageous to the company. That the contract was intra vires provided that the directors of the company honestly formed the view that the particular business could be carried on advantageously in connection with or ancillary to its main business. Lord Justice Salomon L.J stated as follows: As a matter of pure construction, the meaning of these words seems to me to be obvious. An object of the plaintiff company is to carry on any business which the directors genuinely believe can be carried on advantageously in connection with or as ancillary to the general business of the company. It may be that the directors take the wrong view and in fact the business in question cannot be carried on as the directors believe; but it matters not how mistaken the directors may be. Providing they form their view honestly, the business is within the plaintiff company’s objects and powers. This is so plainly the natural and ordinary meaning of the language of sub-cl (c) that I would refuse to construe it differently unless compelled to do so by the clearest authority; and there is no such authority The rule of ultra vires was finally settled in the case of Rolled Steel Products (Holdings) Ltd v British Steel Corp Rolled Steel Products Ltd gave security to guarantee the debts of a company called SSS Ltd to British Steel Corporation. This was a purpose that did not benefit Rolled Steel Products Ltd. Moreover, Rolled Steel's director, Mr Shenkman was interested in SSS Ltd (he had personally guaranteed a debt to British Steel’s subsidiary Colvilles, which SSS Ltd owed money to). The company was empowered to grant guarantees under its articles but approval of the deal was irregular because Mr Shenkman's personal interest meant his vote should not have counted for the quorum at the meeting approving the guarantee. The shareholders knew of the irregularity, and so did British Steel. Rolled Steel Products wanted to get out of the guarantee, and was arguing it was unenforceable either because it was ultra vires, or because the guarantee had been created without proper authority. At first instance Vinelott J held British Steel’s knowledge of the irregularity rendered the guarantee ultra vires, void and incapable of validation with the members’ consent. British Steel appealed. Held; The Court of Appeal held that the transaction was not ultra vires and void. Simply because a transaction is entered for an improper purpose does not make it ultra vires. Court emphasised the Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 43 distinction between an act which is entered into for an improper purpose (which is not beyond the capacity of a company, or void) and an act which is wholly outside a company's objects (and hence ultra vires and void). However, it was unenforceable because British Steel, with knowledge of the irregularity, could not rely on a presumption of regularity in the company’s internal management. Since British Steel ‘constructively knew’ about the lack of authority, they could acquire no rights under the guarantee. On ultra vires Browne-Wilkinson LJ said the following. In this judgment I therefore use the words "ultra vires" as covering only those transactions which the company has no capacity to carry out, i.e., those things the company cannot do at all as opposed to those things it cannot properly do. The two badges of a transaction which is ultra vires in that sense are (1) that the transaction is wholly void and (consequentially) (2) that it is irrelevant whether or not the third party had notice. It is therefore in this sense that the transactions in In re David Payne & Co Ltd [1904] 2 Ch 608 were held not to be ultra vires. Slade J laid down the principle of ultra vires as follows; (1) The basic rule is that a company incorporated under the Companies Acts only has the capacity to do those acts which fall within its objects as set out in its memorandum of association or are reasonably incidental to the attainment or pursuit of those objects. Ultimately, therefore, the question whether a particular transaction is within or outside its capacity must depend on the true construction of the memorandum. (2) Nevertheless, if a particular act is of a category which, on the true construction of the company’s memorandum, is capable of being performed as reasonably incidental to the attainment or pursuit of its objects, it will not be rendered ultra vires the company merely because in a particular instance its directors, in performing the act in its name, are in truth doing so for purposes other than those set out in its memorandum. Subject to any express restrictions on the relevant power which may be contained in the memorandum, the state of mind or knowledge of the persons managing the company’s affairs or of the persons dealing with it is irrelevant in considering questions of corporate capacity. (3) While due regard must be paid to any express conditions attached to or limitations on powers contained in a company’s memorandum (eg a power to borrow only up to a specified amount), the court will not ordinarily construe a statement in a memorandum that a particular power is exercisable ‘for the purposes of the company’ as a condition limiting the company’s corporate capacity to exercise the power: it will regard it as simply imposing a limit on the authority of the directors (see Re David Payne & Co Ltd [1904] 2 Ch 608). Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 44 (4) At least in default of the unanimous consent of all the shareholders, the directors of a company will not have actual authority from the company to exercise any express or implied power other than for the purposes of the company as set out in its memorandum of association. (5) A company holds out its directors as having ostensible authority to bind the company to any transaction which falls within the powers expressly or impliedly conferred on it by its memorandum of association. Unless he is put on notice to the contrary, a person dealing in good faith with a company which is carrying on an intra vires business is entitled to assume that its directors are properly exercising such powers for the purposes of the company as set out in its memorandum. Correspondingly, such a person in such circumstances can hold the company to any transaction of this nature. (6) If, however, a person dealing with a company is on notice that the directors are exercising the relevant power for purposes other than the purposes of the company, he cannot rely on the ostensible authority of the directors and, on ordinary principles of agency, cannot hold the company to the transaction. Court therefore held that; In order to be ultra vires a company transaction had to be done in excess of, or outside, the capacity of the company and not merely in excess or abuse of the powers of the company exercised by the directors. Accordingly, whether a transaction was ultra vires depended solely on the construction of the memorandum of association and whether the transaction fell within the objects of the company, properly construed; and a transaction which was within the objects of the company or which was capable of being performed as reasonably ancillary or incidental to the objects was not ultra vires merely because the directors carried out the transaction for purposes which were not within the memorandum of association. LAWTON LJ on the effect of limited liability. It is a legal fiction which has been recognised by the law for over a hundred years. It is said to have helped the growth of innumerable new businesses. The fact that limited liability has all too often enabled many to enrich themselves at the expense of those who have given credit to the companies they control is the price the business world has to pay for the potentiality for growth and convenience which goes with limited liability. The effect of S. 51 on ultra vires; The ultra vires rule is said to be currently of no use with the enactment of S. 51 of the companies Act 2012. However, some of the decisions remain relevant for the purposes of the internal management and control of the company. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 45 Subsection 1 provides that The validity of an act done by a company shall not be called into question on the ground of lack of capacity by reason of anything contained in the company’s memorandum. Thus, ultra vires as either a defence by the company or by a contracting party to an action to enforce a contract is no longer possible. This brings about as much protection as is possible for a contractor against the ultra vires rule. One should note, however, that sub-s (2) provides that: (2) A member of a company may bring proceedings to restrain the doing of an act which but for sub-s (1) would be beyond the company’s capacity; but no such proceedings shall lie in respect of an act done in fulfilment of a legal obligation arising from a previous act of the company. This preserves the right of members to restrain by injunction the company from acting outside the objects clause and, therefore, in breach of the S.21 contract. But this right is lost once, for example, an ultra vires contract proposed by the company has been signed with the contracting party. This ‘internal aspect’ to ultra vires is further preserved by sub-s (3), which provides that: 3.The directors shall observe any limitations on their powers contained in the company’s memorandum, and any action by the directors which but for subsection (1) would be beyond the company’s capacity may only be ratified by the company by special resolution. However, as the subsection 4 continues: 4) A resolution ratifying the action under subsection (3) shall not affect any liability incurred by the directors or any other person and relief from the liability must be agreed to separately by special Simon Goulding in his book COMPANY LAW notes that; the directors will be liable to reimburse the company for losses it sustains while engaging upon an activity outside the objects clause and, although it is now provided that the members can ratify and adopt by special resolution an otherwise ultra vires act which is quite different from the position which before, any such resolution will not, of itself, relieve the directors from liability and this will have to be done by a separate special resolution. It is difficult to justify a different level of ratification for breaches of directors’ duties in relation to observing the terms of the memorandum and all other ratifiable breaches of duty where only an ordinary resolution is required. The section must reflect the view that, in relation to the former, the constraints on the directors are still regarded as more fundamental than the latter. Therefore the ultra vires rule is only effective regarding internal management and control of the company but can no longer be raised as a defence or justification once an acthas already been DONE. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 46 GRATUITOUS GIFTS The issue of ultra vires was also involved where a company made or was proposing to make a gratuitous disposition or gift either to its employees or ex-employees or by way of a charitable or political donation. Can a company validly make a gift out of corporate property or asset? The law is that a company has no power to make such payments unless the particular payment is reasonably incidental to the carrying out of a company’s business and is meant for the benefit and to promote the property of the company. This issue was first decided in the case of ; Hutton V West Cork Railway Co. (1893) Ch.d A company sold its assets and continued in business only for the purpose of winding up. While it was awaiting winding up, a resolution was passed in the company’s general meeting authorising the payments of a gratuity to the directors and dismissed employees. The court held that as the company was no longer a going concern such a payment could not be reasonably incidental to the business of the company and therefore the resolution was invalid. In the words of the Lord Justice Bowen said “The law does not say that there are not to be cakes and ale but there are to be no cakes and ale except such as are required for the benefit of the company” This means that Therefore, gifts and expenditure on employees to keep and maintain a contented workforce were acceptable but not after the company had ceased to be a going concern or had gone into liquidation. The company could no longer have an interest in a motivated workforce and, therefore, gratuitous redundancy payments would be ultra vires. The question is, suppose there is a clause in the Memorandum of Association that such payments shall be made, is payment ultra vires? The authority that dealt with this position was the case of RE LEE BEHRENS & CO. [1932] 2 Ch. D 46 The object clause of the company contained an express power to provide for the welfare of employees and ex employees and also their widows, children and other dependants by the grant of money as well as pensions. Three years before the company was wound up, the Board of Directors decided that the company should undertake to pay a pension to the widow of a former managing director but after the winding up the liquidator rejected her claim to the pension. The court held that the transaction whereby the company covenanted to pay the widow a pension was not for the benefit of the company or reasonably incidental to its business and was therefore ultra vires and hence null and void. Justice Eve stated as follows Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 47 Whether they reneged an express or implied power, all such grants involved an expenditure of the company’s money and that money can only be spent for purposes reasonably incidental to the carrying on of the company’s business and the validity of such grants can be tested by the answers to three questions: Is the transaction reasonably incidental to the carrying on of the company’s business? Is it a bona fide transaction? Is it done for the benefit and to promote the prosperity of the company? These questions must be answered in the affirmative. The question may be posed as to whether these tests apply where there is an express power by the objects. This is one area where the courts are still insistent that creditors’ security must be reserved. Parke v. Daily News [1962] 2 Ch.d 927 In this case the company transferred the major portion of its assets and proposed to distribute the purchase price to those employees who are going to become redundant after reduction in the stock of the company of the company’s business. The company was not legally bound to make any payments by way of compensation. One shareholder claimed that the proposed payment was ultra vires. The court held that the proposed payment was motivated by a desire to treat the ex-employees generously and was not taken in the interest of the company as it was going to remain and that therefore it was ultra vires. The Court observed as follows “ the defendants were prompted by motives which however laudable and however enlightened from the point of view of industrial relations were such as the law does not recognise as sufficient justification. The essence of the matter was that the Directors were proposing that a very large part of its assets should be given to its employees in order to benefit those employees rather than the company and that is an application of the company’s funds which the law will not allow.” Evans v. Brunner Mound & Co. 1921 Ch.d 359 The company carried on the business of chemical manufacturers. Its object clause contained a power to do all such things as maybe incidental or conducive to the attainment of its objects. The company distributed some money to some universities and scientific institutions, which was meant to encourage scientific education and research. The company thereby hoped to create a reservoir of qualified scientists from which the company could recruit its staff. The court held that even though the payment was not under an express power, it was reasonably incidental to the company’s business and therefore valid. This is one of the few cases where payment was recognised as being valid. Son of Loyola Anthony Ferdinandius AMDG 48