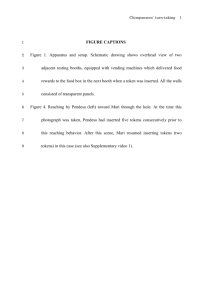

1 question 6. Title of the essay: The Role of Projections and Multimodal Signaling in “Seamless” Turn-Taking Exam candidate number: SBXX4 Word count: 1200 (only the body of the text, not including this first page or the reference list at the end) 1 2 question 6. Introduction Conversations are interactive (with speakers and recipients) and founded on smooth, normative turn exchanges: “on-time” speaker transition, with minimal overlap/gap (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2017). A (multi-unit) turn is composed of one (several) turn-constructional unit(s) or TCU(s) (unit: sentence/clause/phrase/word); the distribution of turns is specified by turn-allocational techniques: “current-speakerselects-next” or “self-selection” (Sacks et al., 1974). Given the discrete and alternating nature of turns and turn-taking, how can conversations be so seamless? Predicting turn completion points – using linguistic cues – is essential for turn-taking in “successful” conversations: predictions help speakers prepare for their future turn (Sjerps & Meyer, 2015: speech planning occurs towards the end of turns), while turn-allocational techniques help choose the next speaker. Readily available multimodal sensory cues support these fast transitions. In multi-unit (sentential/clausal) turns, the linguistic features (syntactic and prosodic) of early TCUs influence later ones within the turn (“projection”); the projectability of TCUs makes turn completion points predictable to current recipients (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2017). In English, speakers heavily rely on the syntactic construction of turns for the projection of clausal units, since the fixed Subject-Verb-Object word order is highly common (thus predictable), allowing for early projectability (see Table 1); using their syntactic knowledge, conversational partners can, early on, predict turn completion points, (Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen, 2005). This is arguably expandable to other syntactically regular languages, whose fixed word orders are commonly used (see Table 1: Turkish). One implication is that patterns of conversational interactions might differ in less syntactically regular languages where predictions cannot be made early on; Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen (2005) used conversation samples from Tanaka’s corpora (2000) to highlight the differences between Japanese (where turns 2 question 6. 3 are recurrently and incrementally built: late projectability) and English in next-turn onset: although potential next-speakers of both languages orient to the end of the current clause to add their next turn, English speakers are aided by the S-V-O structure (or “subject first, predicates after” rule, more generally), whereas Japanese speakers do not expect clausal referents like subjects and objects to be explicitly expressed (or they are “predicate-final”, alternatively). We might (1) infer that given this syntax-based account, predicting completion points via turn projectability is not one robust explanation for smooth turn-taking and (2) hypothesise that turn transitions in conversations are faster in English than Japanese. Regarding (1), conversations also often lack units with clear syntactic structures, even in otherwise regular languages (e.g., in casual settings, or simply transitioning from the written to spoken modality). However, Stivers et al’s statistical analyses on 10 language samples (2009) indicated that Japanese has the fastest mean turn transition time (7ms) – faster than English (236ms). This implies that Japanese speakers predict completion points, perhaps earlier and/or more accurately than English speakers; this is implausible in the syntax-based account of turn projectability. What resolves this conflict is that turn projectability is not solely syntactic-based but can also depend on prosodic regularities (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2017): indeed, Tanaka’s analysis (2000) on Hayashi’s Japanese corpora revealed that speakers use marked prosody to project turn completion; such prosodic contours are used in predictions, in addition to the recognition of utterance-final elements (since Japanese has a strong predicate-final orientation). Tanaka (2000) argued that these two mechanisms (“devices”) can precisely localise possible transition-relevance places and compensate for the delayed syntactic turn projectability. Thus, the inference in (1) is unfounded, given that prosody also influences TCU projection; speakers of late-projectability languages with less regular syntax can rely more on prosodic contours. Interactions between syntactic and prosodic influences are likely key in speakers’ predictions: 3 question 6. 4 illustratively, English speakers also make use of prosody. In parallel-opposition constructions, “current-speaker” can hold the floor for a second, opposing clause by using prosodic cues: e.g., prolonging their intonation into a follow-up turn (BarthWeingarten, 2009: “continuing intonation”). Within-turn projections (syntactic, prosodic) are picked up by recipients to form context-sensitive inferences about turn completion points, which facilitates turntaking in naturally flowing conversations. Multimodal sensory cues – visual, auditory – in conversational settings support this inference-based, fast turn-taking system. Visual cues aid speakers in taking turns while talking in person. Auer (2021) took a multimodal approach to analyse turn-taking, focusing on speakers’ gaze. He analysed six one-hour recordings of three-party student interactions, containing gaze data for each conversationalist; other, “maximal” cues were also coded (e.g.: use of “you” and gaze; naming and gaze; pointing; combinations of cues…). In the majority (86%) of turn transitions, the participant gazed at, towards the end of the current turn (before reaching completion point), by the current speaker took the next turn: gaze alone seems to be a robust signal in next-speaker selection. Whether gaze alone is a stronger predictor of next-speaker than combinations of gaze and verbal cues (“you”, naming…), and whether conversationalists rely more on it than projection-based predictions of completion points remain open questions; but, since gaze signals are ubiquitous in conversations, they may strongly support – along other sensory and linguistic cues – turn-taking via the current-speaker-selects-next rule. Mondada (2007) examined the occurrence of pointing gestures in a corpus of professional, roundtable meeting recordings (15hours); pointing was coded as a sequence of preparation-stroke-retraction. Most pointing began before the completion point of the current turn (“pre-initial turn pointings”), and fully extended at the next turn-initial position: Mondada’s (2007) example (3) illustrates this scenario, where, using 4 5 question 6. pointing, the recipient (Laura) anticipated and signaled her (next) turn. Although looking at a specific interaction that incites pointing (i.e., with maps on a meeting table), this study suggests that recipients use gestures to support turn-taking: in roundtable professional meetings, they exploit within-turn pointing to signal imminent self-selection, to project the current turn completion point. Studies examining casual, face-to-face conversations also point at the help of gestures in turn-taking: questions with gestures were answered significantly faster (shorter transition delays) than questions without gestures, even after controlling for prosody and gaze (Holler et al., 2018). Recipients use verbal cues to signal self-selection and take the next turn. Marian et al. (2021) examined a rare conversational scenario: multi-unit turns where the first unit repeats the preceding single-unit turn uttered by another speaker (“resaying”). They gathered 30 such cases from different corpora (audio/videos), languages (English/French/Spanish), interactional settings. In their corpus, re-saying was used to express understanding of prior talk (of the past speaker) and extend the current turn: recipients produce this first unit to instantiate their turn (then hold the floor by adding more units). Critically, to decide when to take turn, speakers make use of both visual and auditory cues, in a complementary fashion. Participants discriminated between turn-ends and turn-continuations better in the presence of audiovisual information than audio-only, while auditory information sufficed for them to time their response at turn-end; having audiovisual information enabled the early prediction of next turn (Latif et al., 2018). Visual and auditory signals thus convey complementary information for turn-taking: for the early prediction of the next turn exchange and the precise timing of a response at turn end, respectively. Conclusion Turn-taking is fundamental to our ability to hold meaningful conversations, exchange ideas; indeed, people take turns when talking in-person. They rely on 5 question 6. 6 linguistic – stemming from the projectability of TCUs – and multimodal cues to predict turn completion points, signal and take future turns. Importantly, a working turn-taking system, although essential, is only one facet of successful in-person communication. 6 7 question 6. References: (not included in the word count) Auer, P. (2021). Turn-allocation and gaze: A multimodal revision of the “current- speaker-selects-next” rule of the turn-taking system of conversation analysis. Discourse Studies, 23(2), 117-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445620966922 Barth-Weingarten, D. (2009). Contrasting and turn transition: Prosodic projection with parallel-opposition constructions. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(11), 2271-2294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.03.007 Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (2017). Turn Construction and Turn Taking. Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction (pp. 31111). Cambridge University Press. Holler, J., Kendrick, K. H., & Levinson, S. C. (2018). Processing language in face-toface conversation: Questions with gestures get faster responses. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 25(5), 1900-1908. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1363-z Latif, N., Alsius, A. & Munhall, K.G. (2018) Knowing when to respond: the role of visual information in conversational turn exchanges. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 80(1), 27-41. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-017-1428-0 Marian, K. S., Malabarba, T., & Weatherall, A. (2021). Multi-unit turns that begin with a resaying of a prior speaker's turn. Language & Communication, 78, 77-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2021.01.004 7 question 6. 8 Mondada, L. (2007). Multimodal resources for turn-taking: Pointing and the emergence of possible next speakers. Discourse Studies, 9(2), 194-225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607075346 Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243 Sjerps, M. J., & Meyer, A. S. (2015). Variation in dual-task performance reveals late initiation of speech planning in turn-taking. Cognition, 136, 304-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.10.008 Stivers, T., Enfield, N. J., Brown, P., Englert, C., Hayashi, M., Heinemann, T., Hoymann, G., Rossano, F., Peter de Ruiter, J., Yoon, K.-E., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). Universals and Cultural Variation in Turn-Taking in Conversation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS, 106(26), 1058710592. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903616106 Tanaka, H. (2000). Turn Projection in Japanese Talk-in-Interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 33(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3301_1 Thompson, S. A., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2005). The clause as a locus of grammar and interaction. Discourse Studies, 7(4/5), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054403 8 9 question 6. Appendix Table 1 Basic Syntactic Structure of Two Syntactically “Regular” Languages Sentential TCUa Word Order English Turkish Maya is going to her friend’s house. Maya arkadaşının evine gidiyor. Subject - Verb - Object Subject - Object - Verb Maya -> S Maya -> S is going -> V arkadaşının evine -> O to her friend’s house -> O gidiyor -> V Note. The Turkish sentence is a literal translation of the English sentence. a Equivalent to one, complete turn (hypothetical, for illustration purposes). Decomposition 9

![What is cooperation? “getting along” o [Not fighting]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015676631_1-98b0d3ea59c9c23c897e78fcf6af183c-300x300.png)