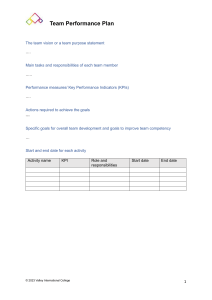

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 Selection of Key Performance Indicators for Your Sport and Program: Proposing a Complementary ProcessDriven Approach Jo Clubb, BSc,1 Sian Victoria Allen, PhD,2 and Kate K. Yung, PT, PhD3,4,5 Global Performance Insights, United Kingdom; 2Product Innovation, Lululemon Athletica, Vancouver, Canada; 3 Medical and Performance Innovations, Kitchee Sports Club, Hong Kong SAR, China; 4Centre for Data Science, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; and 5Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 1 ABSTRACT Key performance indicators (KPIs) are commonplace in business and sport. They offer an objective means to link data and processes with performance outcomes. Yet, their application in sports performance, particularly team sports, is not without issue. Here, we review 4 key issues relating to KPI application in team sports; lack of a universal definition, complexity of performance, drifting from on-field performance goals with off-field targets, and agency issues across different key stakeholders. With these issues relating to sports performance KPIs in mind, we propose a complementary approach to help practitioners focus on implementing the conditions that create performance environments and opportunities for success in a complex sporting Address correspondence to Jo Clubb, jo. clubb@acu.edu.au. environment. Ongoing process trackers (OPTs) are quantifiable measures of the execution of behaviors and processes that create the environments, cultures, and conditions for successful performance outcomes. This approach equips sports science practitioners with key questions they can ask themselves and their team when starting to select and use OPTs in their program. INTRODUCTION ey performance indicators (KPIs) are used to evaluate the performance of a sports team, department, staff, and/or athletes themselves (12). They are commonplace in business (52) and sports (30,35) on account of the many benefits they offer. Some examples include enabling objective evaluation of an organization, team, or individual in meeting performance goals (28), informing training and K practice decisions (25), and directly being able to predict competition performance from KPIs (44,60). Despite their ubiquity and copious benefits, some issues still exist with their use in sports performance. These include potential detrimental effects of measurement itself on athlete behaviors (24,41), and concern with how well KPIs can truly approximate performance in complex dynamic events such as team sports (35). Furthermore, the increasing attention on sports performance support and abundance of available data may induce pressure to use KPIs to quantify the value of performance support and try to demonstrate return on investment (12,31). Conversely, practitioners are keen to KEY WORDS: sports science; sports performance; key performance indicators; objectives and key results; athlete monitoring Copyright Ó National Strength and Conditioning Association 90 VOLUME 46 | NUMBER 1 | FEBRUARY 2024 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 demonstrate how the data amassed and the subsequent interventions used have a positive impact on performance. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to discuss the issues with using KPIs in team sports performance support. Based on these issues, we propose a new framework, ongoing process trackers (OPTs). This approach, which could be used in conjunction with KPIs, is intended to help sports performance practitioners better select and track indicators of the processes that ultimately underpin sports performance. CURRENT LANDSCAPE OF KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS IN SPORTS PERFORMANCE Striving for peak performance is a central tenet of sporting endeavor. Thus, it follows that sport staff will seek indicators that underpin performance on an organizational, departmental, and individual level. Indeed, a recent organizational staff structure for team sports proposed that performance staff, including practitioners across sports science, strength and conditioning, nutrition, and psychology, and team sport staff, made up of coaching and scouting staff among others, each provide expertise related to specific KPIs (11). Although the use of KPIs is relevant for team sport staff, in this article, we focus our discussion predominantly as it relates to performance staff. One recent framework (12) has outlined the following steps for performance staff to use KPIs in a sporting setting. Identify what it takes to succeed Define the performance model Determine KPIs Assess the athlete Plan and deploy the program of interventions Review A performance model can be dissected into the following determinants: physiologic demands, technical requirements, tactical requirements, psychological skills, equipment characteristics, health aspects, and rules and regulations (12). In individual time–distance-based sports, the determinants of performance may be more straightforward. For instance, structural equation modeling in swimming explained 79% of performance in young male athletes based on biomechanical and energetic profiles (4). Only variables that can be assessed by performance staff were included in the model and given the high prediction of swim performance demonstrated, it follows that the variables identified can therefore be used for training control and evaluation (4). Such division of determinants offers performance staff an understanding of the underpinning qualities to performance, such as the physical capacities that can be developed to enable the athlete to meet, and potentially surpass, the physical demands of the sport. Associations between jump power and heading success, and strength (predicted 1 repetition maximum from a 3 repetition maximum test) and tackle success in elite youth soccer may warrant development of such physical capacities, for example (59). In addition, increases in reactive strength (measured via drop jump performance) have been associated with reductions in sprint times, whereas increases in power (via countermovement jump performance) were associated with improvements in change of direction abilities in elite female soccer players (20). However, team sports performance offers greater complexity than can often be broken down into linear determinants of success (1). As such, simple deterministic approaches, such as those used in individual time–distancebased sports, may be less suitable. Therefore, the current approach to applying KPIs in the team sport environment warrants a critical review. ISSUES AND CHALLENGES WITH KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS In reviewing KPIs through a critical lens, we have identified 4 areas of concern for their current application in team sports. They are as follows. Definition: Lack of a universal definition Complexity: Isolated metrics overlook the complexity of performance Goodhart’s law: The threat of drifting from on-field performance with offfield targets Agency issues: Different stakeholders often have competing interests In this section, we will delve into each of these issue areas in further detail. LACK OF A UNIVERSAL DEFINITION Although many researchers have aimed to formalize the definition of KPIs for different sectors (18,36,40), there remains a lack of universal agreement, especially in sport. Given the widespread familiarity with the term, it may be believed that a universal definition is unnecessary. Yet, potential misuse of terminology is a long-time cause for discussion in sports science (34,54). One recent definition in sports science is: “a quantifiable measure used to evaluate the success of an organization or employee in meeting a performance objective” (12). A performance objective is subsequently illustrated as winning a league, tournament, or other championship, achieving a specific time, distance, or mass lifted in centimeter-gram-second sports, or beating the opposition in tactical events (12). Clearly in this instance, clarity of the collective performance objective is required for KPIs to be effective. Yet, this definition of KPIs is firmly linked to a single-outcome measure. Meanwhile, other definitions use the properties of the measure itself, asserting that KPIs should be a valid measure of performance, an objective measurement using a known scale of measurement, and provide a valid way of interpretation (42). To add further confusion, similar but different terminology, such as “performance indicators” (30) also exists. A performance indicator is “a selection, or combination, of action variables that aims to define some or all aspects of a performance” (30). In team sports, the relationship between performance indicators and match outcome has been explored in Australian rules football (48), soccer (13) and rugby union (33). In this context, performance indicators are statistical actions that can be used to evaluate teams and individual 91 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Strength and Conditioning Journal | www.nsca-scj.com Key Performance Indicators athletes, including which indicators are likely to result in a winning outcome. Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 It is clear from these various definitions that a useful performance indicator should relate to successful performance or outcome. These applications traditionally sit within the performance analysis realm of team sports. However, these definitions lack guidance for how such KPIs can be used in practical terms. The focus on statistical actions during match play also limits their use to the wider multidisciplinary performance staff. It is therefore unclear how current definitions of KPIs relate to sports science data collection. Such ambiguity may fuel agency issues with how different stakeholders consider, interpret, and use data in relation to their interpretation of the term KPI. ISOLATED METRICS OVERLOOK THE COMPLEXITY OF PERFORMANCE As performance staff increasingly seek to relate sports science data to performance, it seems (at least to the authors) that KPIs may have become synonymous with broader terms such as metrics or variables, confusing the issue further. This is perhaps because of the abundance of metrics, thanks to the expansion of data collection in today’s sporting environments. Indeed, a recent article described how the increase in data streams within the contemporary training environment may cloud parsimonious and valid applications if not used appropriately (31). It may also be because of the breaking down of sports performance into silos in traditional fields such as physiology, biomechanics, and performance analysis (53), in which the term “performance indicator” may have a specific context. Previous literature has categorized performance indicators into match classification (e.g., score, number of shots on targets), biomechanical (e.g., optimal release angle for javelin throw (7)), technical (e.g., passes to oppositions (32)), and tactical (e.g., passes and possessions (30)). Yet, consideration is warranted as to whether each of these categories and individual indicators truly reflect performance, and if so, how they combine to do so. One of the reasons why individual indicators may not truly reflect performance is because sports performance, particularly in team sports, is a complex entity (3). As such, team performance is not only achieved by qualities of the individual athletes (e.g., technical skills or physical abilities), but also the emerging pattern from the dynamic interaction between individuals, their opponents, and environments (51). Therefore, the impact of using isolated or specific measures as KPIs, such as physical running output captured by in-game tracking technologies, is often limited (10,15). Furthermore, different leagues may require different physical or technical KPIs to best approximate performance (16). As well as overarching consideration for context, such as league or position, more nuanced contextual factors are often lacking in developing KPIs. Phatak et al. (46) recently demonstrated the need to account for phase of play and other contextual factors such as ball possession. For example, accounting for ball possession changes the interpretation of fouls as a KPI in soccer (46). Caution is therefore warranted when it comes to labeling data as KPIs, particularly isolated metrics that lack contextual narratives. DRIFTING FROM ON-FIELD PERFORMANCE WITH OFF-FIELD TARGETS Performance staff attempt to translate their understanding of what it takes to succeed into performance goals (12). Drifting from these on-field performance goals is a threat, because it may result in time and attention being placed on areas less meaningful to performance. This may be driven by the different motivations of various stakeholders within team sports, as we shall discuss in the next section. In addition, using targets from objective measurements may underpin a drift from performance goals. This is exemplified by Goodhart’s law. Named after British economist Charles Goodhart, the common adaptation of the decree is by Marilyn Strathern: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” When outcomes are complex, as demonstrated by sport performance, a single measure cannot represent them. This is why there is rarely (if ever) a single KPI; the complexity of performance warrants multiple. Even within specific disciplines, physical development for example, a single measurement is often underpinned by a multitude of factors. This is illustrated by low predictive relationships between acceleration and lower limb strength and power, for example, indicating a complex interaction between sprint technique and leg muscle performance (37). Therefore, if each indicator is imperfectly correlated with the goal of performance, concentrating on them in isolation may inadvertently create unwanted distractions and inefficient application of resources. This has been exemplified elsewhere in areas such as academic publishing (21), higher education (19), and government spending (29) to name a few. Although using KPIs as targets can drive processes that have positive effects on performance, Goodhart’s law serves as a reminder that targets may distract from the goal of on-field sporting performance. Given the limited time and resources available to performance staff, these must be spent on the most impactful contributors to performance. Lower limb strength and power measures may frequently be converted into targets for athletic development, but although meaningful, they do not solely account for performance. Although strength and maximal power were the best discriminators of playing level in rugby league, they still only accounted for 12–17% of the variation in playing level (1). Similarly, KPIs that focus on vertical force production, such as those derived from countermovement jump performance, may overlook the importance of horizontal force production and therefore, limit transference of gym-based strength to on-field performance (47). Beyond the issue of time efficiency, performance staff are in danger of “naive interventionism” if potential 92 VOLUME 46 | NUMBER 1 | FEBRUARY 2024 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 harmful effects of so-called performance targets are not considered (55). Indeed, iatrogenics (“caused by the healer” in Greek) represents a treatment that causes more harm than good (55). Goodhart’s law may underpin iatrogenics in sports performance that result from turning measures into evaluations. In some cases, this may have been witnessed through the assessment of total distance covered as measured by tracking technology, which has been reported to have led to some athletes running around during breaks in play simply to increase their distance covered (23). Similarly, velocity based training provides objective feedback on bar velocity numbers during strength work, which can improve training intent, but with poor implementation could encourage athletes to chase targets to the detriment of technique, and potentially safety (23). Another example is performance staff may set targets to address asymmetries assessed through strength and power testing, such as ,10% interlimb asymmetry for return to sport from injury (8,38). However, clinicians have also acknowledged that the unaffected limb is rarely normal (43) and research has yet to demonstrate a clear influence of asymmetry on performance (8,39). Further research is warranted to understand whether intervention planning to target asymmetry reduction is beneficial (43). A final example may be setting bodyweight targets, which could lead to athletes engaging in unhealthy weight loss behaviors. For example, 22% of youth American football players given bodyweight targets in order to be selected to compete were deemed to be at risk of abnormal eating behaviors, with eating binges, excessive exercise and drastic weight loss methods such as sauna use reported (61). Such body-mass manipulation can lead to dehydration that may affect performance in subsequent training activities (6), and similar thermal weight loss techniques have been described as “concerning” in combat sports (5). Despite good intentions, such emphasis on metrics has the potential to adversely affect the quality of output and can distract from, or even replace the original purpose (23). Therefore, performance staff should use continuous reflection and intention to ensure any targets introduced serve their central goal of enhancing sports performance. DIFFERENT STAKEHOLDERS OFTEN HAVE COMPETING INTERESTS KPIs can be different for different stakeholders. In business, organizations have multiple stakeholders reflecting multiple functions (52). Similarly in sport, different stakeholders can be seen as competitors with different motivations and means to achieve them (22). For example, physical preparation staff may seek to set high training load targets to maximize performance, whereas medical staff seek to control training load to minimize risk of injury (22). However, agency problems and conflict may arise if performance staff select these KPIs in relative isolation, without considering the interests of all involved stakeholders, even if well-intentioned. For example, an injured athlete may be concerned about their place in the team and an upcoming contract extension, and thereby wanting to play as soon as possible, whereas the medical staff are predominantly concerned about the rehabilitation and subsequent re-injury risk. Nevertheless, the team sport staff (e.g., coaches) would like the player to compete in an imminent important game, because they are concerned about the team’s winning percentage. When the above stakeholders’ KPIs do not align, it may lead to tension within the sports organization. To resolve these kinds of agency problems, performance staff and team sport staff may adopt a shared decision-making model when making decisions regarding rehabilitation (62). Expansion of this model, however, is needed to better support them in how to go about selecting their KPIs or performance-focused measures. Indeed, the rehabilitation setting may warrant greater attention to KPIs, given the more controlled nature of returning an athlete from injury, and potential tension between physical performance and medical staff during such an interdisciplinary process (22). KPIs may cover medical (e.g., palpation pain and range of motion), physical (e.g., high-speed running and accelerations), and technical aspects (e.g., passing and tackling) (56). Time and/or clinical markers for return to play may also be seen as a KPI (9). Although these markers may not necessarily be named KPIs per se, they serve similar purposes in evaluating the player’s performance and gauging their progression in RTP. When performance is placed as the primary goal, competition between key stakeholders should disappear. Performance-focused measures determined in an interdisciplinary manner can bring stakeholders together as teammates (22). For instance, greater preseason participation has been associated with lower in-season injury risk (58); therefore, the so-called training loadinjury paradox is actually in the best interest of physical preparation and the medical staff. Targets for injury availability may also be used, given the relationship between injuries and chance of success demonstrated across a variety of sports (12). It remains clear, however, that differing responsibilities within the performance staff, in addition to the wider team sport staff, can threaten agency issues when incorporating KPIs in applied practice. A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR PERFORMANCE INDICATORS: ONGOING PROCESS TRACKERS One of the main reasons KPIs are used so broadly is that they provide many well-established benefits in supporting individuals, teams, and organizations in monitoring progress toward desired performance goals. However, given some of the issues highlighted above, complementing KPIs with other tools may offer a more complete approach to evaluating performance progress over the longterm. Here, we propose a new approach to KPIs that may offer a solution to any unintended consequences associated with traditional KPIs and a complementary means to help more holistically track and support the progress of athletes or teams toward performance goals. 93 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Strength and Conditioning Journal | www.nsca-scj.com Key Performance Indicators Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 Ongoing process trackers are quantifiable measures of the execution of behaviors and processes that create the environments, cultures, and conditions for successful performance outcomes. Where traditional KPIs are often based on metrics that directly serve outcome goals, OPTs focus on measuring how well an athlete or team are adhering to the pathway toward achieving specific outcomes. The rationale for the development of OPTs thus stems heavily from literature describing the developmental pathway to peak performance of top athletes, and literature related to the interplay between process and outcome for supporting successful sporting performance. Specifically, one of the key Table 1 Characteristics of effective OPTs Characteristic Long-term Actions Establish a bold vision, then align and commit to the long-term goals it will take to achieve the vision as a multidisciplinary team Applied examples Team promoted to the first division after 3 years Develop the leading physical preparation program in the league. Evidenced by scoring the most points in the latter stages of games Focused on the processes and behaviors Assemble the necessary multidisciplinary Each athlete understands and can articulate the “why” behind their expertise and bring all stakeholders that constitute the pathway to physical preparation program together performance success Breakdown long-term goals into the steps Each athlete completes a designated number of personalized physical it will take to achieve them harnessing preparation sessions a month this expertise All athletes are on time for all training Acknowledge the complex and nonlinear Use a basket of OPTs sessions nature of performance Think about the environment, conditions, All athletes bring the right kit and and culture you want to create to equipment to all training sessions facilitate long-term success and develop OPTs to help reinforce these Represent and engage all key stakeholders Medical: each athlete completes a full Include at least one OPT per key blood panel every 3 mo to optimize stakeholder group opportunity for physical adaptation Allow key stakeholders to design their own Psychology: each athlete completes OPTs to best support identified longreflective practice journaling after each term goals physical preparation session to seek Communicate all stakeholder OPTs for full opportunities to accelerate learning and transparency and alignment development Contextual Consider different ways to appropriately assess OPTs, such as observational measures Adapt OPTs as needed based on new information, learnings, and context Prevention of Goodhart’s law Antigoal: Athletes having to get up early to Develop “antigoals” attend a mandatory team recovery If KPIs are also used, review alongside OPTs session the day after a match or to ensure outcomes and processes are competition, compromising their sleep continually assessed (see below) and ironically, their recovery and ongoing physical development Integration of OPTs and KPIs Experienced athlete with perfect Olympic Consider the learning and skill lifting technique: focus on hitting development phase of individual specific testing numbers athletes and their readiness for focusing Lesser experienced athlete: focus on on processes or outcomes Olympic lifting technique development, for example, integrating and executing specific coaching cues or drills Improvements to running technique, as observed and assessed by multiple practitioners and/or coaches 94 VOLUME 46 | NUMBER 1 | FEBRUARY 2024 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 factors distinguishing “super-elite” athletes (Olympic and/or World Champions) from “elite” athletes (international representatives but nonmedalists) in a multidisciplinary developmental biography study (27) was the joint focus of super-elites on mastery and outcome goals, whereas elite athletes demonstrated a strong outcome focus only. In addition, although superelite athletes reported similar training volumes and training characteristics in adulthood, their continued performance improvement compared with elite athletes was attributed in significant part to the positive psychosocial characteristics of their training environment related to their mastery orientation (26). Furthermore, in team sports, a perceived mastery climate created by coaches and performance staff is a stronger predictor of player performance than individual psychological factors such as mental toughness and grit (45). Indeed, focusing on the process over the outcome has long been a strategy favored by top coaches to help athletes manage the challenges and stressors associated with performance under pressure (14). Equally, a recent metaanalysis concluded that using process goals had a much larger positive effect on athlete performance (d 5 1.36) compared with performance goals (d 5 0.44). Process goals can be effective when set in isolation (57). That said, other research has shown that performance is best served by focusing on process goals for areas of learning and development, with a switch to outcome focuses for areas of mastery (63). Practically speaking, we suggest that practitioners may wish to integrate OPTs and KPIs into their measurement practice, potentially with individualized approaches for different athletes. Borrowing from the business world, many top companies such as Google, Amazon, and Uber have successfully used a goal system called objectives and key results (OKRs) to help set goals and track progress toward them (17). Where traditional KPIs are often fixed and act to monitor the day-to-day health of a system (e.g., 80% squad availability), OKRs are agile and designed to also hold teams to bold and ambitious long-term goals (e.g., become the top injury management program in the league). Thus, we have adapted several elements key to the success of OKRs in this framework, in the hope that this will help practitioners effectively implement OPTs within their program. Table 1 presents the characteristics of OPTs with corresponding actions for practitioners, along with applied examples. By helping to focus athletes, departments, and/or entire teams and organizations on the process over the outcome, complementing KPIs with OPTs may offer several potential advantages over traditional KPIs alone. First, by their design, they aim to reinforce behaviors that contribute to performance success, helping to avoid the negative consequences of Goodhart’s law—these positive behaviors function as measures and targets that are helpful for performance (24). Conversely, they can include “antigoals,” behaviors or approaches that should be avoided to meet the OPTs. This feature would ensure that performance is never inadvertently compromised to achieve targets. Second, given the complexity of human performance, even our best predictive models populated by reams of data still struggle to help us understand how the multiple variables traditionally assigned as KPIs combine to contribute to team sport performance, particularly in openskill sports such as soccer, basketball, and Australian rules football (35). Instead, OPTs would help acknowledge these unknowns and would be intended to help tip an athlete’s or team’s odds in favor of success. Third, they offer the capacity to harness the experience, intuition, and context of practitioner and coaching teams in defining the processes for success in ways that traditional KPIs Figure 1. A checklist infographic for selecting and using OPTs. 95 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Strength and Conditioning Journal | www.nsca-scj.com Key Performance Indicators Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 based solely on data-driven targets often neglect (24). Even in a data-abundant sports performance environment, it warrants remembering that not everything that can be measured matters, and not everything that matters can be measured (49). In addition, OPTs may also help drive talent development in a team, program, or organization by creating a culture that encourages younger or less-experienced athletes to model the positive behaviors of more experienced athletes, and helping to incentivize the value of long-term athlete development, and short-term performance outcomes (2). Finally, by encouraging athletes to focus on controllable factors, OPTs may offer the ancillary benefit of fostering athlete autonomy and intrinsic motivation (50), helping prevent burnout and supporting athlete well-being while facilitating long-term performance success. goals rather than a sole focus on outcome measures. Using a basket of OPTs allows different key stakeholders to engage and align to support the behaviors that can lead to long-term goals of an organization. Practitioners can use the OPT checklist (Figure 1) to track and demonstrate how their program supports process-driven goals. Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors report no conflicts of interest and no source of funding. Jo Clubb is a sports science consultant at her company, Global Performance Insights. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Multiple strategies may support the effective implementation of OPTs in sports performance environments. Given the multitude of data now collected, combined with the nonlinear relationship to performance, using OPTs may also help practitioners demonstrate the buy-in and success of a program with some distance from on-field outcomes. Figure 1 displays a checklist with key questions performance staff practitioners can ask themselves and their team when starting to select and use OPTs in their program. 12. Sian Victoria Allen is a physiologist working in industry R&D at lululemon athletic. 13. 14. 15. 16. Kate K. Yung is a researcher and the Director of Medical and Performance Innovations at Kitchee S.C. CONCLUSION Despite widespread adoption, using KPIs can be problematic given the complex and nonlinear nature of team sports performance. This concern is compounded by the growing data abundance and multidisciplinary practitioners within the performance staff, which can cause a drift from on-field performance goals and agency issues across different stakeholders. Given these issues, we propose a complementary framework, OPTs, that shifts attention to the processes that underpin performance. These are quantifiable measures of the behaviors and processes that create the environment for success, underpinned by mastery 3. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. REFERENCES 1. 2. Baker DG, Newton RU. Comparison of lower body strength, power, acceleration, speed, agility, and sprint momentum to describe and compare playing rank among professional rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res 22: 153–158, 2008. Baker J, Schorer J, Wattie N. Compromising talent: Issues in identifying and selecting talent in sport. Quest 70: 48–63, 2018. 23. Balague N, Torrents C, Hristovski R, Davids K, Araújo D. Overview of complex systems in sport. J Syst Sci Complex 26: 4–13, 2013. Barbosa TM, Costa M, Marinho DA, Coelho J, Moreira M, Silva AJ. Modeling the links between young swimmers’ performance: Energetic and biomechanic profiles. Pediatr Exerc Sci 22: 379–391, 2010. Barley OR, Chapman DW, Abbiss CR. Weight loss strategies in combat sports and concerning habits in mixed martial arts. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 13: 933–939, 2018. Barr SI. Effects of dehydration on exercise performance. Can J Appl Physiol 24: 164–172, 1999. Best RJ, Bartlett RM, Sawyer RA. Optimal javelin release. J Appl Biomech 11: 371–394, 1995. Bishop C, Turner A, Read P. Effects of inter-limb asymmetries on physical and sports performance: A systematic review. J Sports Sci 36: 1135–1144, 2018. Brinlee AW, Dickenson SB, Hunter-Giordano A, Snyder-Mackler L. ACL reconstruction rehabilitation: Clinical data, biologic healing, and criterion-based milestones to inform a return-to-sport guideline. Sports Health 14: 770–779, 2022. Brito Souza D, López-Del Campo R, Blanco-Pita H, Resta R, Del Coso J. Association of match running performance with and without ball possession to football performance. Int J Perform Anal Sport 20: 483–494, 2020. Calleja-González J, Bird SP, Huyghe T, et al. The recovery umbrella in the world of elite sport: Do not forget the coaching and performance staff. Sports 9: 169, 2021. Cardinale M. Key performance indicators. In: NSCA’s Essentials of Sport Science. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc, 2022. Castellano J, Casamichana D, Lago C. The use of match statistics that discriminate between successful and unsuccessful soccer teams. J Hum Kinetics 31: 137–147, 2012. Dehghansai N, Pinder RA, Baker J, Renshaw I. Challenges and stresses experienced by athletes and coaches leading up to the Paralympic Games. PLoS ONE 16: e0251171, 2021. Del Coso J, Brito de Souza D, Moreno-Perez V, et al. Influence of players’ maximum running speed on the team’s ranking position at the end of the Spanish LaLiga. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 8815, 2020. Dellal A, Chamari K, Wong DP, et al. Comparison of physical and technical performance in European soccer match-play: FA premier league and La liga. Eur J Sport Sci 11: 51–59, 2011. Doerr J. Measure What Matters: OKRs: The Simple Idea That Drives 10x Growth. London, United Kingdom: Portfolio Penguin, 2018. Domı́nguez E, Pérez B, Rubio ÁL, Zapata MA. A taxonomy for key performance indicators management. Comput Stand Inter 64: 24–40, 2019. Elton L. Goodhart’s law and performance indicators in higher education. Eval Res Educ 18: 120–128, 2004. Emmonds S, Nicholson G, Begg C, Jones B, Bissas A. Importance of physical qualities for speed and change of direction ability in elite female soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 33: 1669–1677, 2019. Fire M, Guestrin C. Over-optimization of academic publishing metrics: Observing Goodhart’s law in action. GigaScience 8: giz053, 2019. Gabbett TJ, Whiteley R. Two training-load paradoxes: Can we work harder and smarter, can physical preparation and medical Be teammates? Int J Sports Physiol Perform 12: S250–S254, 2017. Gamble P. Prepared: Unlocking Human Performance With Lessons From Elite Sport. Informed in Sport Publishing, 2020. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Prepared-UnlockingHuman-Performance-Lessons/dp/177521866X. Accessed April 12, 2023. 96 VOLUME 46 | NUMBER 1 | FEBRUARY 2024 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 24. Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywC X1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 02/04/2024 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. Gamble P, Chia L, Allen S. The illogic of being datadriven: Reasserting control and restoring balance in our relationship with data and technology in football. Sci Med Football 4: 338–341, 2020. Groom R, Cushion C, Nelson L. The delivery of video-based performance analysis by England youth soccer coaches: Towards a grounded theory. J Appl Sport Psychol 23: 16–32, 2011. Güllich A, Hardy L, Kuncheva L, et al. Developmental biographies of olympic super-elite and elite athletes: A multidisciplinary pattern recognition analysis. J Expert 2: 23–46, 2019. Hardy L, Barlow M, Evans L, Rees T, Woodman T, Warr C. Great British medalists: Psychosocial biographies of super-elite and elite athletes from Olympic sports. Prog Brain Res 232: 1–119, 2017. Herold M, Kempe M, Bauer P, Meyer T. Attacking key performance indicators in soccer: Current practice and perceptions from the elite to youth academy level. J Sports Sci Med 20: 158–169, 2021. Hood C, Piotrowska B. Goodhart’s law and the gaming of UK public spending numbers. Public Perform Manag Rev 44: 250–271, 2021. Hughes MD, Bartlett RM. The use of performance indicators in performance analysis. J Sports Sci 20: 739–754, 2002. James LP, Talpey SW, Young WB, Geneau MC, Newton RU, Gastin PB. Strength classification and diagnosis: Not all strength is created equal. Strength Cond J 45: 333–341, 2023. James N. Notational analysis in soccer: Past, present and future. Int J Perform Anal Sport 6: 67– 81, 2006. Jones NMP, Mellalieu SD, James N. Team performance indicators as a function of winning and losing in rugby union. Int J Perform Anal Sport 4: 61–71, 2004. Knuttgen HG, Kraemer WJ. Terminology and measurement in exercise performance. J Strength Cond Res 1: 1–10, 1987. Lames M, McGarry T. On the search for reliable performance indicators in game sports. Int J Perform Anal Sport 7: 62–79, 2007. Lindberg C-F, Tan S, Yan J, Starfelt F. Key performance indicators improve industrial performance. Energ Proced 75: 1785–1790, 2015. Lockie RG, Jalilvand F, Callaghan SJ, Jeffriess MD, Murphy AJ. Interaction between leg muscle performance and sprint acceleration kinematics. J Hum Kinetics 49: 65–74, 2015. Maestroni L, Read P, Bishop C, Turner A. Strength and power training in rehabilitation: Underpinning principles and practical strategies to return 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. athletes to high performance. Sports Med 50: 239–252, 2020. Maloney SJ. The relationship between asymmetry and athletic performance: A critical review. J Strength Cond Res 33: 2579–2593, 2019. Maté A, Trujillo J, Mylopoulos J. Conceptualizing and specifying key performance indicators in business strategy models. In: Conceptual Modeling (Vol. 7532). Atzeni P, Cheung D, and Ram S, eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012. pp. 282–291. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3642-34002-4_22. Accessed December 20, 2022. McGuigan M. Monitoring Training and Performance in Athletes. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2017. O’Donoghue P. Research Methods for Sports Performance Analysis. Routledge, 2009. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/ 9781134005369. Accessed December 20, 2022. Paton BM, Read P, Van Dyk N, et al. London international consensus and delphi study on hamstring injuries part 3: Rehabilitation, running and return to sport. Br J Sports Med 57: 278–291, 2023. Perl J, Memmert D. A pilot study on offensive success in soccer based on space and ball control —key performance indicators and key to understand game dynamics. Int J Comput Sci Sport 16: 65–75, 2017. Pettersen SD, Martinussen M, Handegård BH, Rasmussen L-MP, Koposov R, Adolfsen F. Beyond physical ability—predicting women’s football performance from psychological factors. Front Psychol 14: 1146372, 2023. Available at: https:// www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg. 2023.1146372/full. Accessed April 4, 2023. Phatak AA, Mehta S, Wieland F-G, et al. Context is key: Normalization as a novel approach to sport specific preprocessing of KPI’s for match analysis in soccer. Sci Rep 12: 1117, 2022. Randell AD, Cronin JB, Keogh JW, Gill ND. Transference of strength and power adaptation to sports performance—horizontal and vertical force production. Strength Cond J 32: 100–106, 2010. Robertson S, Back N, Bartlett JD. Explaining match outcome in elite Australian Rules football using team performance indicators. J Sports Sci 34: 637–644, 2016. Rosling H, Rosling O, Rönnlund AR. Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong about the World—and Why Things Are Better Than You Think. London, United Kingdom: SCEPTRE, 2018. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55: 68– 78, 2000. Salmon PM, McLean S. Complexity in the beautiful game: Implications for football research and practice. Sci Med Football 4: 162–167, 2020. Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 3. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2004. Springham M, Walker G, Strudwick T, Turner A. Developing strength and conditioning coaches for professional football. Coaching Prof Football 50: 9–16, 2018. Staunton CA, Abt G, Weaving D, Wundersitz DWT. Misuse of the term “load” in sport and exercise science. J Sci Med Sport 25: 439–444, 2022. Taleb NN. Antifragile: How to Live in a World We Don’t Understand: London, United Kingdom: Allen Lane, 2012. Whiteley R, van Dyk N, Wangensteen A, Hansen C. Clinical implications from daily physiotherapy examination of 131 acute hamstring injuries and their association with running speed and rehabilitation progression. Br J Sports Med 52: 303–310, 2018. Williamson O, Swann C, Bennett KJM, et al. The performance and psychological effects of goal setting in sport: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 1–29: 2022. Windt J, Gabbett TJ, Ferris D, Khan KM. Training load–injury paradox: Is greater preseason participation associated with lower in-season injury risk in elite rugby league players? Br J Sports Med 51: 645–650, 2017. Wing CE, Turner AN, Bishop CJ. Importance of strength and power on key performance indicators in elite youth soccer. J Strength Cond Res 34: 2006–2014, 2020. Yang G, Leicht AS, Lago C, Gómez M-Á. Key team physical and technical performance indicators indicative of team quality in the soccer Chinese super league. Res Sports Med 26: 158–167, 2018. Yeargin S, Torres-McGehee TM, Emerson D, Koller J, Dickinson J. Hydration, eating attitudes and behaviors in age and weight-restricted youth American football players. Nutrients 13: 2565, 2021. Yung KK, Ardern CL, Serpiello FR, Robertson S. A framework for clinicians to improve the decisionmaking process in return to sport. Sports Med Open 8: 52, 2022. Zimmerman BJ, Kitsantas A. Developmental phases in self-regulation: Shifting from process goals to outcome goals. J Educ Psychol 89: 29– 36, 1997. 97 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Strength and Conditioning Journal | www.nsca-scj.com