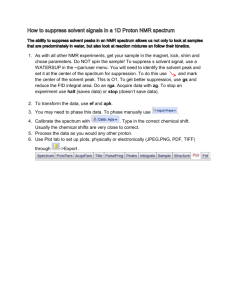

8.1.1 Thin-Layer Chromatography DOWNLOAD PDF Thin Layer Chromatography: Basics Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) is a technique used to analyse small samples via separation o For example, we could separate a dye out to determine the mixture of dyes in a forensic sample There are 2 phases involved in TLC - stationary phase and mobile phase Stationary phase o This phase is commonly thin metal sheet coated in alumina (Al2O3) or silica (SiO2) o The solute molecules adsorb onto the surface o Depending on the strength of interactions with the stationary phase, the separated components will travel particular distances through the plate o The more they interact with the stationary phase, the more they will 'stick' to it Mobile phase o Flows over the stationary phase o It is a polar or nonpolar liquid (solvent) or gas that carries components of the compound being investigated o Polar solvents - water or alcohol o Non-polar solvents - alkanes If the sample components are coloured, they are easily identifiable We can examine the plate under UV light using ninhydrin to identify uncoloured components Conducting a TLC analysis Step 1: Prepare a beaker with a small quantity of solvent Step 2: On a TLC plate, draw a horizontal line at the bottom edge (in pencil) This is called the baseline Step 3: Place a spot of pure reference compound on the left of this line, then a spot of the sample to be analysed to the right of the baseline and allow to air dry The reference compounds will allow identification of the mixture of compounds in the sample Step 4: Place the TLC plate inside the beaker with solvent - making sure that the pencil baseline is lower than the level of the solvent - and place a lid to cover the beaker The solvent will begin to travel up the plate, dissolving the compounds as it does Step 5: As solvent reaches the top, remove the plate and draw another pencil line where the solvent has reached, indicating the solvent front The sample’s components will have separated and travelled up towards this solvent front A dot of the sample is placed on the baseline and allowed to separate as the mobile phase flows through the stationary phase; The reference compound/s will also move with the solvent Rf values A TLC plate can be used to calculate Rf values for compounds These values can be used alongside other analytical data to deduce composition of mixtures Rf values can be calculated by taking 2 measurements from the TLC plate Exam Tip The baseline on a TLC plate must be drawn in pencil. Any other medium would interact with the sample component and solvents used in the analysis process. Interpreting & Explaining Rf Values in TLC The less polar components travel further up the TLC plate o Their Rf values are higher than those closer to the baseline o They are more soluble in the mobile phase and get carried forwards with the solvent More polar components do not travel far up the plate o They are more attracted to the polar stationary phase The extent of separating molecules in the investigated sample depends on the solubility in the mobile and stationary phases Knowing the Rf values, of compounds being analysed, helps to compare the polarity of various molecules 8.1.2 Gas/Liquid Chromatography: Basics DOWNLOAD PDF Gas/Liquid Chromatography: Basics Gas-Liquid Chromatography (GLC) is used for analysing: o Gases o Volatile liquids o Solids in their vapour form The stationary phase: o This method uses a column for the stationary phase o A non-polar, long-chain, non-volatile hydrocarbon with a high boiling point is mounted onto a solid support o Small silica particles can be packed into a glass column to offer a large surface area o Sample gas particles travel through this phase and are able to separate well due to the large surface area The Mobile phase o An inert carrier gas (eg. Helium, Nitrogen) moves the sample molecules through the stationary phase Retention times Once sample molecules reach the detector, their retention times are recorded o This is the time taken for a component to travel through the column The retention times are recorded on a chromatogram where each peak represents a volatile compound in the analysed sample Retention times are then compared with data book values to identify unknown molecules A gas chromatogram of a volatile sample compound has six peaks. Depending on each molecule’s interaction with the stationary phase, each peak has its own retention time 8.1.3 Interpreting Rf Values in GL Chromatography DOWNLOAD PDF Interpreting Rf Values in GL Chromatography Features of a gas-liquid chromatogram Peaks represent different molecules from the sample - each roughly taking the shape of a triangle The area under each peak is the relative concentration of each component (the peak integration value) Area under the peak = ½ x base x height If the area under each peak is very small or too difficult to decipher, the height of peaks are used for further analysis To find the area under each peak, treat each peak as a triangle - see the examples shown using blue triangles in the diagram Percentage composition of a mixture We can calculate the amount of a particular molecule in a sample by using an expression If a chromatogram shows peaks for alcohols A, B, C and D, to calculate the % composition of alcohol C, use this expression: Explain Retention Times Retention time is the time taken for a sample molecule to travel through the column, from the time it is inserted into the machine to the time it is detected Molecules in the gaseous mixture travel at different rates, therefore giving rise to different retention times Longer retention times are associated with: o Non-polar components in the mixture o They are more attracted to the non-polar liquid in the stationary phase o So non-polar molecules travel slower through the column Shorter retention times are associated with: o Polar components in the mixture that prefer to interact with the carrier gas o They are less attracted to the non-polar liquid in the stationary phase o So polar molecules travel faster through the column o These molecules may have lower boiling points, therefore are vapourised more readily 8.1.4 Interpreting & Explaining Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy DOWNLOAD PDF Interpreting & Explaining Carbon-13 NMR Spectra Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is used for analysing organic compounds Atoms with odd mass numbers usually show signals on NMR o For example isotopes of atoms o Many of the carbon atoms on organic molecules are carbon-12 o A small quantity of organic molecules will contain the isotope carbon-13 atoms o These will show signals on a 13C NMR In 13C NMR, the magnetic field strengths of carbon-13 atoms in organic compounds are measured and recorded on a spectrum Just as in 1H NMR, all samples are measured against a reference compound – Tetramethylsilane (TMS) On a 13C NMR spectrum, non-equivalent carbon atoms appear as peaks with different chemical shifts Chemical shift values (relative to the TMS) for 13C NMR analysis table Features of a 13C NMR spectrum C NMR spectrum displays sharp single signals – there aren’t any complicated spitting pattern as seen with 1H NMR spectra The height of each signal is not proportional to the number of carbon atoms present in a single molecular environment CDCl3 is used as a solvent to dissolve samples for 13C NMR o On spectra, a single solvent peak appears at 80 ppm caused by 13C atoms in the CDCl o This can be ignored when interpreting 13C spectra 13 Identifying 13C molecular environments On an organic molecule, the carbon-13 environments can be identified in a similar way to the proton environments in 1H NMR For example propanone o There are 2 molecular environments o 2 signals will be present on its 13C NMR spectrum There are 2 molecular environments in propanone The 13C NMR of propanone showing 2 signals for the 2 molecular environments 8.1.5 Proton (1H) NMR Spectroscopy DOWNLOAD PDF Interpreting & Explaining Proton (<sup>1</sup>H) NMR Spectra Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is used for analysing organic compounds Atoms with odd mass numbers usually show signals on NMR In 1H NMR, the magnetic field strengths of protons in organic compounds are measured and recorded on a spectrum Protons on different parts of a molecule (in different molecular environments) emit different frequencies when an external magnetic field is applied All samples are measured against a reference compound – Tetramethylsilane (TMS) o TMS shows a single sharp peak on NMR spectra, at a value of zero o Sample peaks are then plotted as a ‘shift’ away from this reference peak o This gives rise to ‘chemical shift’ values for protons on the sample compound o Chemical shifts are measured in parts per million (ppm) Features of a NMR spectrum NMR spectra shows the intensity of each peak against their chemical shift The area under each peak gives information about the number of protons in a particular environment The height of each peak shows the intensity/absorption from protons A single sharp peak is seen to the far right of the spectrum o This is the reference peak from TMS o Usually at chemical shift 0 ppm A low resolution 1H NMR for ethanol showing the key features of a spectrum Molecular environments Hydrogen atoms of an organic compound are said to reside in different molecular environments o Eg. Methanol has the molecular formula CH3OH o There are 2 molecular environments: -CH3 and -OH The hydrogen atoms in these environments will appear at 2 different chemical shifts Different types of protons are given their own range of chemical shifts Chemical shift values for 1H molecular environments table Protons in the same molecular environment are chemically equivalent Each peak on a NMR spectrum relates to protons in the same environment Low resolution 1H NMR Peaks on a low resolution NMR spectrum refers to molecular environments of an organic compound o Eg. Ethanol has the molecular formula CH3CH2OH o This molecule as 3 separate environments: -CH3, -CH2, -OH o So 3 peaks would be seen on its spectrum at 1.2 ppm (-CH3), 3.7 ppm (-CH2) and 5.4 ppm (-OH) A low resolution NMR spectrum of ethanol showing 3 peaks for the 3 molecular environments High resolution 1H NMR More structural details can be deduced using high resolution NMR The peaks observed on a high resolution NMR may sometimes have smaller peaks clustered together The splitting pattern of each peak is determined by the number of protons on neighbouring environments The number of peaks a signal splits into = n + 1 (Where n = the number of protons on the adjacent carbon atom) High resolution 1H NMR spectrum of Ethanol showing the splitting patterns of each of the 3 peaks. Using the n+1, it is possible to interpret the splitting pattern Each splitting pattern also gives information on relative intensities o E.g. a doublet has an intensity ratio of 1:1 – each peak is the same intensity as the other o In a triplet, the intensity ratio is 1:2:1 – the middle of the peak is twice the intensity of the 2 on either side H NMR peak splitting patterns table 1 8.1.6 Use of Tetramethylsilane (TMS) DOWNLOAD PDF Use of Tetramethylsilane (TMS) In NMR spectroscopy, Tetrametylsilane (TMS) is used as a reference compound The organic compound is dissolved in TMS before being introduced to the magnetic field of the spectrometer It is an ideal chemical to use as a reference o TMS is inert and volatile o This reduces undesirable chemical reactions with the compound to be analysed o It also mixes well with most organic compounds TMS gives a single sharp peak on the NMR spectrum and is given a value of zero The molecular formula of TMS is Si(CH3)4 o There are 12 hydrogens in this molecule o All of the protons are in the same molecular environment. Therefore gives rise to just one peak o This peak has a very high intensity as it is accounting for the absorption of energy from 12 1H nuclei Tetramethylsilane (TMS) – Si(CH3)4 When peaks are recorded from the sample compound, they are measured and recorded by their shift away from the sharp TMS peak This gives rise to the chemical shift values for different 1H environments in a molecule H NMR spectrum for TMS showing it’s signal at 0 ppm 1 8.1.7 Deuterated Solvents in Proton NMR DOWNLOAD PDF Deuterated Solvents in Proton NMR When samples are analysed through NMR spectroscopy, they must be dissolved in a solvent Tetramethylsilane (TMS) is a commonly used solvent in NMR Despite TMS showing one sharp reference peak on NMR spectra, the proton atoms can still interfere with peaks of a sample compound To avoid this interference, solvents containing Deuterium can be used instead o For example CDCl3 o Deuterium (2H) is an isotope of hydrogen (1H) Deuterium nuclei absorb radio waves in a different region to the protons analysed in organic compounds Therefore, the reference solvent peak will not interfere with those of the sample Use of D20 in Identifying O-H & N-H Protons Identifying -OH & -NH signals on a 1H NMR spectrum The proton in -OH is not affected by its neighbouring molecular environments As a result, the hydrogen atom of -OH group appears as a singlet This is due to the hydrogen atom readily exchanging with hydrogens atoms of water molecules or any acid that may be present When interpreting 1H NMR spectra of amines and amides, the same exchanging phenomenon can be seen Protons of these functional groups exchanging leads to changes in their chemical shift ranges This table shows the range of chemical shifts for -OH and -NH- protons Their surrounding molecular environment has a direct impact on this range The range of chemical shifts for -OH & -NH- protons table Using D2O Deuterium oxide (D2O) can be added to correctly identify -OH and -NH- protons Adding a small quantity of this solvent ‘removes’ the peaks from the spectrum The -OH proton and the -NH proton both undergo the same exchanging process as seen before. This time with a deuterium atom (D) of D2O