Is Inheritance Justified? Philosophy & Public Affairs Article

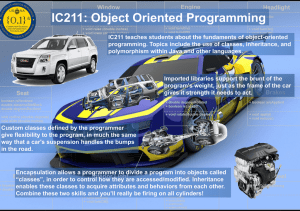

advertisement