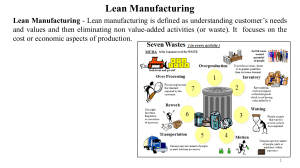

LEAN DEFINITION AND HISTORY. LEAN MANAGEMENT: the core idea of Lean Mnagement is to maximize customer value while minimizing the waste. Simply, lean means creating more value for customers with fower resources. JIT aims to meet demand instantaneously, with perfect quality and no waste. The TRADITIONAL APPROACH assumes that each stage will place the parts it produces in an inventory which buffers that stage from the next one downstream in the total process. The next stage down will then take the parts form the inventory, process them, and pass them through to the next buffer inventory. The larger the buffer inventory, the greater is the degree of insulation, and therefore the less is the disruption caused when a problem occurs. This insulation has to be paid for in terms of inventory and slow throughput times, but it does allow each stage to operate in an uninterrupted, and therefore efficient, manner. When a problem occurs at one stage, the problem will not immediately be apparent elsewhere in the system. The responsability of solving the problem will be centred largely on the staff within that stage. In the JUST IN TIME APPROACH, parts are produced and then passedd directly to the next stage “Just in Time” to be processed. Probelms at any stage have a different effect in such a system. For example, now if stage A stops production, stage B will notice immediately and stage C very soon after. Stage A’s problem is now quickly exposed to the whole system and the whole system is affected by th eproclem. One result os this is that the responsability for solving the problem is no longer confined to the staff at stage A but now is shared by everyone. This considerably improves the chances of the problem being solved; in other words, by preventing inventory from accumulating between stages, the operation has increased the chances of the intrinsic efficiency of the plant being improved. Both approaches seek to encourage high efficiency in the operation, but they take different routes to doing so. Traditional Approaches seek to encourage efficiency by protecting each part of the operation from disruption. Long, uninterrupted production runs its ideal state. JIT Approach takes the opposite view. Esposure of the system to problems can both make them more evident and change the “motivation structure” of the whole system towards solving problems. JIT sees inventory as a “blanket of obscurity” which lies over the production system and prevents problems being noticed. Ideally, JIT requires: QUALITY must be high because disruption iin production due to quality errors will slow down the trhoughput of materials, reduce the internal dependability of supply, and prossibly cause inventory to build up if errors slow theproduction rate. SPEED, in ter,s of fast trhoughput of materials, is essential if customer demand is to be met directly from production rather than form inventory. DEPENDABILITY is a prerequisite for fast trhoughput, or put the opposite way, it is difficult to achieve fast troughput if the supply of parts or the reliability of equipment is not dependable. FLEXIBILITY is especially important in order to achieve small batch sizes and therefore fast throughput and short delivery lead times. As a result of excellence is above performance objectives, COST is reduced. In JIT, the main sacrifice is Capacity Utilization. When production stoppages occur in the Traditional System, the buffers allow each stage to continue working and thus achieve high capacity utilization. The high utilization does not necessarily make the system as a whole produce more parts. Ofter the extra production goes into the large buffer inventories. When production stoppages occur in the JIT System, any stoppage will affect the rest of the system, causing stoppages throughput th eoperation. This will necessarily lead to lower capacity utilization, at least in the short term. However, HIT argues that there is no point in producing output just for its own sake. Unless the output is useful and causes the operation as a whole to produce saleable products, thereis no point in producing it anyway. In fact, producing just to keep utilization high is not only poit-less, it is couter-productive, because the extrainventory produced marely serves to make imrpovements less likely. 3 key issues define the core of JIT philosophy. 1 - - - ELIMINATION OF WASTE. Waste can be defined as any activity which does not add value. Identifying waste is the first step to eliminate it. Toyota identified 7 types of waste, which have been found to apply in many different rypes of operations, both service and production, and which form the cose of JIT philosophy: o OVER-PRODUCTION: producing more than is immediately needed by the next process in the operation is the grearest souce of waste according to Toyota. o WAITING TIME: machine efficiency and labour efficiency are two popular measures which are widely used to measure machine and labour waiting time, respectively. Lass obvious is the amount of waiting time of materials, disguised by operators who are kept busy producing WIP which is not needed at the time. o TRNSPORT: moving materials around plant, together with the double and triple handling of WIP, does not add value. Layout changes which bring processes closer together, improvements in tranport methods and workplace organization can all reduce waste. o PROCESS: the process itself may be a source of waste. Some operations may only exist because of poor component design, or poor maintenance, and so could be eliminated. o INVENTORY: under a JIT Philosophy, all inventory becomes a target for elimination. However, it is only by tackling the causes of inventory that it can be reduced. o MOTION: an operration mau look busy, but sometimes no value is being added by the work. Semplification of work is a rich souce of rreduction in the waste of motion. o DEFECTIVE GOODS: quality waste is often very significant in operations, even if actual measures of quality are limited. INVOLVEMENTS OF EVERYONE. JIT Philosophy is often put forward as a “Total System”. Its aim is to provide guidelines which embrace everyone and every process in the organization. An organization’s culture is seen as being important in supporting these objectives trhough an emphasis on involving all of the organization’s staff. The JIT Apporach to people management has also been called the “respect-for-humans” system: it enourages and often requires team.based problem-solving, job enrichment, job rotation and multi-skilling. The intention is to encourage a high degree of personal responsability, engagement and ownership of the job. CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT - KAIZEN. JIT objectives are often expressed as ideals, such as our previous definition: “to meet demand istantanously with perfect quality and no waste”. While any organization’s performance may be far removed form such ideals, a funamental belief belief of JIT is that it is possible to get closer to them over time. Witout such beliefs to drive progress, JIT proponents claim imrpovement is more likely to be transitory than continuous. If the aims of JIT are set in terms of ideal which individual organizations may never fully achieve, then the emphasis must be on the way in which the organization moves closer to the ideal state. The Japanese word for continuous improvement is Kaizen. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZmBQRmDgIc Companies must have a general cleaner to be in line with the JIT main elements. To do this, most of the companies follow a process called FIVE S: SORT OUT. STANDARDIZE. SET IN ORDER. SUSTAIN. SHINE. Every comoany needs to realize that the customer is the reason the company continues to exist and each customer will only return if its cost/quality/delivery stanadars are met. To meet these standards, employees must create and deliver only what the customers are willing to pay for. Companies need to develop a Customer-Based Approach. Satisfaction of employees is a necessary condition for improvement. When starting a Lean Journey, many factories begin by looking at the factory floor for imporrvements, since there is where the customer value is being added. A good way to start is to performe a Waste Walk on the floor, looking for Excessive 2 Inventory, Waste of Trasportation, Waste of Waiting, Waste of Motion, Waste of Processes, Waste of Defects, Waste of Over-Production (it is the worst one because it amplifies all the others). Why Mass Production is not the best choice? The increasing speed of change in the business enviroment requires flexible firms. Customer desires become more and more individual. The greater global competition boosts firms to have: o Higher efficiency. o Increased innovation and process speed. o Higher flexibility within processes. o Higher quality requirements. JIT is the Western embodiment of a philosophy and series of techniques developed by the Japanese. The philosophy is founded on doing the simple things well, on gradually doing them better and on sqeezing out waste every step of the way. Leading the ddevelopment of JIT in Japan has been the Toyota Motor Company. Toyota’s strategy in Japan has been progressively to interface manifacturing more closely with its customers and suppliers. It has done this developing a set of practices which has largerly shaped what we now call JIT. Indeed some would argue that the origins of JIT lie within Toyota’s reaction to the “oil shock” of rising oil prices in the early 1970s. The need for improved manifacturing efficiencies that this provoked spurred Toyota, and other Japanese manfacturers, were undoubtedly encouraged by the national cutlure and economic circumstances. Japan’s attitude towardds waste, together with its position as a crowded and virtually naturally resourceless country, produced ideal conditions in which to devise a manifacturing philosophy which emphasizes low waste and high added value. An alternative explanation of JIT’s origins looks back to the Japn’s shipbuilding industrry: in late 1950s and early 1960s, over-capacity among Japan’s steelmakers meant tuat shipbuilders could demand deliveries of steel precisely when they wanted them. Because of this, this shipbuilders improved production methods so that they could reduce their steel inventories from about one month’s worth to three days’ worth. As the advantages of low-stockbuilding became apparent, the idea spread to other parts of Japanese industry. 3 5 LEAN PRINCIPLES. MUDA means WASTE: specifically, any human activity which absorbs resources but creates no value. Taiichi Ohno, the Toyota executive who was the most ferocious foe of waste of human history has produced, identified the first seven types of Muda. LEAN THINKING is the most powerrful antidote to Muda. Lean Thinking is “Lean” because it provides a way to do more and more with less and less: less human effort, less equipment, less time, and less space – while coming closer and closer to providing customers with exactly what they want. It also provides a way to make woek more satisfying by providing immediate feedback on efforts to convert Muda into value. And it provides a way to create new work rather than simply destroying jobs in the name of efficiency. 1. DEFINE / SPECIFY VALUE: Define value from the customer viewpoint is the 1st step of Lean Thinking. The critical strarting point for Lean Thinking is Value. Value can only be defined by the ultimate customer. And it’s only meaningful when expressed in terms of a specific product (a good, a service, and often both at once) which meets the customer’s needs at a specific price at a specific time. Value is created by the producer. How to identify value? Ask every time: Why is this necessary for the customer? Which processes would not be noticed by the customer if we did not do them? The more we do of this activity, the happier is the customer and he/she pays me for that? How products and processes are related to the customer’s needs on: Price? Quality? Delivery? Quick responses to requests of modifications? Information? Lean Thinking must start with a conscious attempt to precisely define value in terms of specific products with specific capabilities offered at specific prices trhough a dialogue with specific costumers. The way to do this is to ifnore existing assets and technologies and to rethink firms on a product-line basis with storng, dedicated product teams. This also requires redefining the role for firm’s technical experts and rethinking just where in the world to create value. Realistically, no manager can actually implement all of these changes instantly, but it’s essential to form a clear view of what’s really needed. 4 2. MAPPING VALUE (VSM) / IDENTIFY THE VALUE STREAM: - - All activities, value-adding or not, that are necessary to trasform raw materials/info or WIP into final products/delivery services. Identify value consists in mapping the tasks required to bring a specific product trhough two critical processes: The Value Stream is the set of all specific actions required to bring a specific product (whether a good, or service, or, increasingly, a combination of the two) trhough the three critical management tasks of any business: The Problem-Solving Task, running from the concept trhough detailed design and engineering to production launch. The Information-Management Task running from order-taking trhough detailed scheduling to deliverry. The Physical-Trasformation Task proceeding from raw materials to a finished product in the hands of the customer. So, identifying the entire Value Stream for each product (or in some cases for each product family) is the next step in Lean Thinking. - Specifically, the Value Stream Analysis will almost always show that three types of actions are occurring along the Value Stream: Many steps will be found to unambiguosly create value. Many other steps will be found to create no value but to be unavoidable with current technologies and produstion assets: Type One Muda. Many additional steps will be found to create no value and to be immediately avoidable: Type Two Muda. So, Lean Thinking must go beyond the firm, the standars unit of score-keeping in businesses across the world, to look at the whole: the entire set of activities entailed in creating and producing a specific product, from concept trhough detailed design to actual availability, from the initial salethrough order entry and production scheduling to delivary, and from raw materials produced far away and out of sight right into the hands of the customer. The organizational mechanism for doing this is what we call the LEAN ENTERPRISE, a continuing conference of all the concerned parties to create a channel for the entire Value Stream, dredging away all the Muda. Cresting Lean Enterrprises does require a new way to think about firm-to-firm relations, some simple principles for regulating behavior between firms, and trasparency regarding all the steps taken along the value Stream so each partecipant can verrify that the other firms are behaving in accord with the agreed principles. 3. FLOW: From the logic of EBQ/EOQ to one-piece-flow. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciJckWCMvpA 5 : done putting less effort and eliminating something in between that does not matter. How often do we work in batches? Imagine if we all worked closer to one-piece flow. How would it affect our lead times, labor, quality, inventory costs? How would it help our office productivity, customer service, patients, government? These are the questions the company has to ask itself. We all need to fight departmentalized, Batch Thinking because tasks can almost always be accomplished much more efficiently and accurately when the product is worked on continuously from raw material to finished good. In short, things work better when you focus on the product and its needs, rather than the organization or the equipment. Henry Ford and his associates were the first people to fully realize the potential of Flow. Ford reduced the amount of effort required to assemble a Model T Ford by 90% during the fall of 1913 by switching to Continuous Flow in final assembly. Subsequently, he lined up all the machines needed to produce the parts for the Model T in the correct sequence and tried to achieve flow all the way from raw materials to shipment of the finished car, achieving a similar productivity leap. But he only discovered the SPECIAL CASE. His method only worked when production volumes were high enough to justify high-speed assembly lines, when every product used exactly the same parts, and when the same model was produced for many years (nineteen in the case of the Model T). In the early 1920s, when Ford towered above the rest of the industrial world, his company was assembling more than two million Model Ts at dozens of assembly plants around the world, every one of them exactly alike. After World War II, Taïchi Ohno and his technical collaborators concluded that the real challenge was to create Continuous Flow in small-lot production when dozens or hundreds of copies of a product were needed, not millions. This is the GENERAL CASE. Ohno and his associates achieved Continuous Flow in low-volume production, in most cases without assembly lines, by learning to quickly change over tools from one product to the next and by "right-sizing" miniaturizing machines so that processing steps of different types could be conducted immediately adjacent to each other with the object undergoing manufacture being kept in Continuous Flow. Yet, the great bulk of activities across the world are still conducted in departmentalized, batch-and-queue fashion fiftty years after a dramatically superior way was discovered. Why? The most basic problem is that Flow Thinking is counterintuitive; it seems obvious to most people that work should be organized by departments in batches. Then, once tepartments and specialized equipment for making 6 batches at high speeds arre put in place, both the carees aspirations of employees within departments and the calculations of the corporate accountant work powerfully against switching over the flow. So, the Lean Alternative is to redefine the work of functions, departments, and firms so they can make a positive contribution to Value Creation and to speak to the real needs of employees at every point along the stream so it is actually in their interest to make Value Flow. This requires not just the creation of a Lean Enterprise for each product, but also the rethinking of conventional firms, functions, and careers, and the development of a Lean Strategy. 4. PULL PRODUCTION: “Nothing is produced by the upstream provider until the downstream customer signals a need”. Subordinate the production upon the arrival of customer demand. Run the production according to this demand: o Only what is needed. o Only when it is needed. Operations have to be activated only when demand is asking for their products/services. The first visible effect of converting from departments and batches to product teams and flow is that the time required to go from concept to launch, sale to delivery, and raw material to the customer falls dramatically. The ability to design, schedule, and make exactly what the customer wants just when the customer wants it means you can throw away the sale forecast and simply make what customers tell you they need. That is, you can let the customer PULL the product from you as needed rather than pushing products, often unwanted, onto the customer. The demand of customers become much more stable when they know they can get what they want right away and when producers stop periodic price discounting campaigns. 5. PERFECTION: Aim at perfection through continuous improvement (Kaizen): continuously improving the “way to do things”. Thus, Lean Objectives are ideals, Lean Firms stive for getting closerr to them over time. How to pursue Perfection? 7 An example of Continuous Improvement: 5 WHYS TECHNIQUE. Q1: why did the machine stop? o A1: because the fuse blew due to an overload. Q2: why was there an overload? o A2: because the bearing lubrification was inadequate. Q3: why was the bearing lubrification inadequate? o A3: because the lubrification pump was not functioning right. Q4: why wasn’t the lubrification pump working right? o A4: because the pump shaft was worn out. Q5: why was the shaft worn out? o A5: because there was no filter attached where it should be, letting metal-cutting chips in. When speking about Perfection, the have to speak about the importance of the Involvement of Everyone. The system is seen as a TOTAL SYSTEM: everyone and every process in the organization is involved. It is linked also to PEOPLE MANAGEMENT and to RESPECT FOR HUMAN, how? Team-based problem-solving. Job enrichment (maintenance and setup tasks). Job rotation. Multi-skilling. Do not forget the high degree of personal responsability, engagement and ownership of the job. As organizations begin to accurately Specify Value, Identify the entire Value Stream, make the value-creating steps for specific products Flow Continuously, and let the customers Pull Value from the enterprise, something very odd begins to happen. It draws on those involved that there is no end to the process od reducing effort, time, space, cost and mistakes while offering a product which is ever more nearly ehat the customer actually wants. Suddenly Perfection, the fifth principle of Lean Thinking, does not seem like a crazy idea. Why should this be? Because the four initial principles interact with each other in a virtuous circle. Getting value to flow faster always exposes hidden Muda in the value stream. And the harder you pull, the more the impediments to flow are revealed so they can be removed. In addition, although the elimination of Muda sometimes requires new process technologies and new product concepts, the technologies and concepts are usually syrprisingly simple and ready for implementation right now. Perhaps the more important spur to perfection is TRASPARENCY, the fact that in Lean System everyone can see everything, and so it’s easy to discover better ways to create value. What’s more, there is nearly instant and highly positive FEEDBACK for employees making improvements, a key feature of Lean Work and a powerful spur of continuing efforts to improve. Dreaming about Perfection is fun. It is also useful, because it shows wht is possible and helps us to achieve more than we would otherwise. However, even if Lean Thinking makes perfection seem plausible in the long run, most of us live and work in the short run. What are the benefits of Lean Thinking which we can grasp right away? Based on years of benchmarking and observation in organizations around the world, we have developed the following simple rules of thumb: Converting a classic batch-and-queue production system to continuous flow with effective pull by the customer will double labor productivity all the way through the system, while cutting production throughput times by 90% and reducing inventories in the system by 90% as well. Errors reaching the customer and scrap within the production process are typically cut in half, as are job-related injuries. Time-to-market for new products will be halved and a wider variety of products, within product families, can be offered at very modest additional cost. Whats more, the capital investments required will be very modest, even negative, if facilities and equipment can be freed up and sold. And this is just to get started. This is the KAIKAKU bonus released by the initial, radical realignment of the value stream. What follows is continuous improvements by means of KAIZEN en route to perfection. Firms having completed the radical realignment can typically double productivity again through incremental improvements within two to three years and halve again inventories, errors, and lead times during this period. And then the combination of kaikaku and kaizen can produce endless improvements. 8 Lean Thinking is not just the antidote to Muda; it is also the answear to the prolonged economic stagnation in Europe, Japan and North America. Conventional thinking about economic growth focuses on new technologies and additional training and education as key, but the record is not promising. During the past twenty years, we have seen the robotics revolution, the materials revolution, the microprocessor and personal computer revolution, and the biotechnology revolution, yet domestic product per capita in all the developed countries has been firmly stuck. The problem is not with the new technologies themselves, but instead with the fact that they initially affect only a small part of the economy. Stated in another way, most of the economic world, at any given time, is a brownfield of traditioanl activities performed in traditional ways. New technolgoies and augmented human capital may generate growth over the long term, but only Lean Thinking has the demostrated power to produce green shoots of growth all across this landscape within few years. The continuing stagnation in developedd countries has recently led to ugly scapegoating in thepolitical world, as segments of the population in each country push and shove to redivide a fixed economic pie. Stagnation has also led to a frency of cost cutting in the business world, which removes the incentive for employees to make any positive contirbution to their firms and swells the unemployment ranks. Lean Thinking and Lean Enterprise is the solution immeddiately available that can produce results on the scale required. VALUE. A reason firms find it hard to get value rught is that while value creation often flows through many firms, each one tends to define value in a different way to suit its own needs. When these defferent definitions are added up, they often don’t add up. The appropriate definition of the product changes as soon as you begin yo look at the whole through the eyes of the customer. Defining value in the appropriate way is a critical issue. Doing this generally require producers to talk to customers in new ways and for the many firms along the vlaue stream to tak to each other in new ways. It is vital that producers accept the challenge of redefinition, because this is often the key to finding more customers, and the ability to find more customers and sales very quickly is critical to the success of Lean Thinking. This is because lean organizations are always freeing up substantial amounts of resources. If they are to defend their employees and find the best economic use for their assets as they strike out on a new path, they need to find more sales right now. Beginning with a better specification of value can often provide the means. Then, once the initial rethinking of value is done (in what might be called Kaikaku for value), lean enterprises must continually revisit the value question with their product teams to ask if they have really got the best answer. This is the value specification analog of Kaizen which seeks to continually improve product development, order-taking, and production activities. It produces steady results along the path to perfection. The final element in Value definition is the Target Cost. The most important tack in specifying value, once the product is defined, is to determine a Target Cost based on the amount of resources and effort required to make a product of given specification and capabilities if all the currenclty visible Muda were removed from the process. Doing this is the key to sqeeing out the waste. Lean enterprises look at the current bundles of pricing and features being offered customers by conventional firms and then ask how much cost they can take out by the application of Lean Methods. They effectively ask: “What is the Mudafree cost of this product, once unnecessary steps are removed and value is made of flow? Because the target is certain to be far below the costs borne by competitiors, the Lean Enterprise has choices: reduce prices, add features or capabilities to the product, add serrvices to the physical product to create additional value, expand the distribution and service network, or takeprofits to underwrite new products. VALUE STREAM. Once the third set (Type Two Muda) has been removed, the way is clear to go to work on the remaining non-value creating steps (Type One Muda) through the use of the flow, pull, and perfection techniques. In the Cola case, we do not see any steps in the third category which can be immediately eliminated because they are simply redundant. Instead, we see a large number of steps in the second category. They clearly add no value (they are Muda), and they therefore become targets for elimination by application of Lean Techniques. Note that in performing this 9 analysis, we are not “benchmarking” by comparing Tesco’s Cola Value Stream with those of its competitors. In this case, Benchmarking is a waste of time for managers: Lean Benchmarkers who discover their performance is superios to their competitors’ have a natural tendency to relax while mass producers discovering that their performance is inferior often have a hard time understanding exactly why. The main advise is simple: to hell with competitors, compete against perfection by identifying the activities that are Muda and eliminate them. However, to put this admonition to work, you must master the key techniques for eliminating Muda. It all begins with Flow. FLOW. How to make value flow? 1st step: once value is defined and the entire value stream is identified, the first step is to focus on the actual object (the specific design, the specific order, and the prodduct itself) and never let is out of sight from beginning to completion. 2nd step: it makes the first step possibile. It is about ignoring the traditional boundaries of jobs, carrers, functions, and firms to form a Lean Enterprise removing all impediments to the continuous flow of the specific product or product family. 3rd step: it is about rethinking specific work practices and tools to eliminate backflows, scrap, and stoppages of all sort so that design, order, and production of specific product can proceed continuosly. The Lean approach is to create truly dedicated product teams with all the skills needed to conduct value specification, general design, detailed engineering, purchasing, tooling, and production planning in one room in a short period of time usin a proved team decision-making methodology commonly called Quality Function Development (QFD). With a truly dedicated team in place, the design never stops moving forward untile it is fully in production. The result is to reduce development time by getting much higher “hit rate” of products which actually speak to the needs of customers. When a small team is given the mandate to “just do it”, we always find that the professionals suddenly discover that each can successfully cover a much boarder scope of tasks than thay have been allowed previously. They do all the job well and they enjoy it. In Lean Enterprise, Sales and Production Scheduling are core members of product team, in a position to plan the sales campaign ad the product design is being developed and to sell with a clear eye to the capabilities of the production system so that both orders and the product can flow smoothly from sale to delivery. And because there are no stoppages in the porduction system and products are built to order, eith only a few hours elapsed between the first operation on raw materials and shipment of the finished item, orders can be sought and accepted with a clear and precise knowledge of system’s capabilities. There is no expediting. A key technique in ijmplementing this approach is the concept of TAKT Time, which precisely synchronizes the rate of production to the rate of sales to customers. Obviously, the aggregate volumeof orders may increase or decrease over time and Takt Time will need to be adjusted so that production is always precisely synchronized with demand. The point is always to define the Takt Time precisely at a given point in time in relation to demand and to run the whole production sequence precisely to Takt Time. In Lean Enterprise, the production slots created by the Takt Time calculation are clearlyposted. This can be done with a simple whiteboard in production team area at the final assembler, but will probably also involve electronic displays in the assembler firm amd electronic trasmission for display in supplier and customer facilities as well. Complete display, so everyone can see where production stands at every moment, is an excellent example of another critical lean technique, TRASPARENCY or VISUAL CONTROL. Trasparency facilities consistently producing to Takt Time and alerts the whole team immediately to the need either for additional orders or to think of ways to remove waste fi Takt Time needs to be reduced to accommodate an increase in orders. To get manifactures goods to flow, the Lean Enterprise takes the critical concepts of JIT and level scheduling and crries them all the way to their logical conclusion by putting products into continuous flow whenever possible. In Lean Enterprise, the workforce on theplan floor needs to talk contantly to solve production problems and implement improvements in the process. They need to have their professional support staff right by their side and everyone needs to be able to see the status of the entire production system. In the continuous flow layout, the production steps are arranged in a sequence, usually with a single cell, and the product moves from one step to the next, with no buffer of work-in-process in between, using a range of techniques generally 10 labeled “single-piece flow”. To achieve single-piece.flowin the normal situaion when each product family includes many product variants, it is essential that each machine can be converted almost instantly from one product specification to the next. It is also essential that many traditionally massive machines be right-sized to fit directly into the production process. This, is turn, means using machines which are simpler, less automated, and slower than traditional designs. This approach seems completely backward to traditional managers who have been told all their lives that competitive advantage in manifacture is obtained from automating, linking, and speeding up m,assive machinery to increase throughput and remove direct labor. It also seems like common sense that good production management involves keeping every employee busy and everry machine fully utilized, to justify the capital invested in the expensive machines. What traditional managers fail to grasp is the cost of maintaining and coordinating the complate network of high-speed machines making maches. The is the muda of complexity. Because conventional standard-cost accountign systems make machine utilization and employee utilization their key performance measures shile treating in-process inventories as an asset, it is not surprising that managers also fail to grasp that machines rapidly making unwanted parts during 100% of their available hours and employees earnestly performing unneeded tasks during every availabkle minute are only producing Muda. To get continuous-flow systems to flow for more than a minute or two at a time, every machine and every worker must be completely capable. That is, they must always be in proper condition to run precisely when needed and every part must be exactly right. By design, flow systems have an everything-wors-or-nothing-works quality which must be respected and anticipated. This means that the production team must be cross-skilled in every task and that the machinery must be made 100% available and accurate through a series of techniques called TOTAL QUALITY MAINTENANCE (TQM). It also means that work must be rigorously standardized. Machines must be taught to monitor their own work through a series of techniques commonly called POKA-YOKE, or mistake-proofing, which make it impossible for even one defective part to be sent ahead to the next step. These techniques need to be coupled with VISUAL CONTROLS ranging from the 5Ss to status indicators, and from clearly posted, up-todate standard work charts to displays of key measurables and financial information on the costs of the process. The precise techniques vary with the application, but the key principle does not: everyone involved must be able to see and must understand every aspect of the operation and its status at all times. Once the commitment is made to convert to a flow system, striking progress can be made very quickly in the initial Kaikaku Exercise. However, some tools will be unsuited for continuous-flow production and will not be easy to modify quickly. It will be necessary to operate them for an extended perriod in a batch mode, with intermediate bufferrs of parts between the previious and the next production step. The key technique here is to think through tool changes to reduce changeover times and batch sizes to the absolute minimum that existing machinery will permit. This typically can be done very quickly and almost never requires major capital investments. Indeed, if you think you need to spend large sums to convert equipment from lrge batches to small batches or single pieces, you do not yet understand Lean Thinking. The end objective of Flow Thinking is to totally eliminate all stoppages in an entire production process and not to rest in the area of tool design until this has been achieved. MRP still has a use for long-term capacity planning. Work in each cell has to be balanced with the work in every other step so that everyone is worrking to a cycle time equal to Takt Time. When it is necessary to speed up or slow down production, the size of the team may be increased or shrunk, but the actual pace of physical effort is never changed. Only one more flow technique need mentioning: it is to locate both design and physical production in the appropriate place to serve the customer. Work in an organization where value is made to flow continuously creates the conditions foe phychological flow. Every employee has immediate knowledge of whether the job has been done right and can see the status of the entire system. Keeping the system floowing smoothily with no interruptions is a constant challenge, and a very difficult one, but theproduct team has the skills and a way of thinking which is equal to the challenge. And because of the focus on perfection, the whole system is maintained in a permanent creative tension which demands concentration. Any organization can itrosuce flow in any activity. However, if an organization uses Lean Techniques only to make unwanted goods flow faster, nothing but Muda results. How can you be sure you are providing the services and the good 11 prople really want when they really need them? And how can you tie all the parts of a whole value stram together when they cannot be conducted in one continuous-flow cell in one room? Next you need to leand how to PULL. PULL. Pull is the simplest temrs that no one upstream should produce a good or service untile the customer downstream asks for it, but actually following this rule is in practice a bit more complicated. The best way to understand the logic and challenge of Pull Thinking is to start with a real customer expressing a demand for a real product and to work backwards trhough all the steps required to bring the desired product to the customer. The first thing the Toyota Sensei noted at Bumper Works was the massive inventories and batches. Nothing flowed. Immediately right-sizing the massive stamping presses to permit single-piece flow was not possible, so the only solution was to drastically reduce their changeover times and shrink batch sizes. Changeover times were already down from sixteen hours in the mid-1980s to around two hours, but was not nearly enough. The Toyota Sensei applied their standard formula that machines should be available for production about 90% of the time and down for changeovers about 10% of the time. Then they looked at the range fo products Bumper Works would need to make every day. They concluded that the large presses would need to be changed over in twenty-two minutes more or less and the smal presses in ten minutes or less. And so on… As Bumper Works learrned how to pull value through its system, it became capable of responding pratically instantly ro customer orders. Because of its quick changeover ability, Bumper Works could starrt welding a given type of bumper within about twenty minutes of receiving an order and it could easily vary its entire prroduction as demand changed. All that was needed was to drrop a new set of order cards at the welding booth. Similarly, the time elapsed between the arrival of a flat sheet of steel on Bumper Works’s loading dock and the shipment of a finished bumper to the customer fell from an average of four weeks to forty-eight hours. Quality also zoomed, as it always does whenflow and pull thinking are put in place together. The new system gave Bumper Wrols and Chrome Crraft the ability to make small lots of bumpers at short notice, but Khan’s customers did not know how to take advantage of his new capabilities. Untile very recently, even Toyota was still ordering large batches, then erratically changing its orders to create smoothly pulling value stream. Toyota’s distribution system in the 1960s and early 1970s relied on large warehouses in the United States, known as Parts Distribution Centers (PDCs), to store service parts for its vehicles. These parts were shipped from Japan in bulk and stored in massive bins in the warehouses. Dealers placed weekly orders based on estimated demand, often resulting in overstocking or shortages. Toyota encouraged ordering in large batches to save on shipping costs, and it offered expedited shipping for urgent orders at an extra cost to dealers or customers. Despite occasional shortages and reliance on air freight for emergencies, the system operated efficiently and achieved a high fill rate of 98 percent for over fifteen years. In the late 1980s, Toyota realized the need to apply lean thinking to its North American warehousing and distribution system. The existing system operated in a batch-and-queue mode, with inefficient processes for stocking and picking parts. Toyota recognized the opportunity to improve by reducing the size of storage bins and lot sizes for reorders. They proposed ordering parts daily from suppliers and having dealers order daily as well, with Toyota covering the freight costs for daily shipments. This approach would streamline the process, reduce inventory carrying costs, and ensure consistency in orders. Additionally, Toyota aimed to reduce dealer inventories dramatically by ordering parts daily to replace those sold, allowing dealers to carry a wider range of part numbers and better meet customer needs. In the late 1980s, Toyota North American executives understood the logic of implementing a pull system in warehousing that responds to actual customer demand. However, fully implementing this system required years of adaptation for both managers and employees. The process began in 1989 with reducing bin sizes and reorganizing parts based on size and demand frequency. This was followed by introducing standard work and visual control in 1990, where the workday was divided into twelve-minute cycles, and associates were expected to pick or bin a set number of lines during each cycle. Visual control, progress control boards, and exact work cycles helped address disruptions in workflow and provided raw material for continuous improvement activities, known as Kaizen. Kaizen activities involved building new, right-sized work carts and reprogramming Toyota's master computer to group orders by bin location in each Parts Distribution Center (PDC). This allowed for printing picking labels in precise bin order at the beginning of each shift, streamlining the picking process. By August 1995, Toyota was ready to transition from weekly to daily orders from dealers without needing additional staff at the PDCs. The Toyota Daily Ordering System (TDOS) increased productivity significantly compared to traditional methods used by competitors like Chrysler. Additionally, relocating the Parts Redistribution Center (PRC) for Japanese-sourced parts to Ontario, California, reduced replenishment time to the PDCs, enabling a dramatic reduction in stock levels. This ability to reorder in small amounts and quickly resupply parts from the next level of the system led to a significant reduction in total inventories. 12 Toyota realized that implementing a pull system in service parts production and distribution could lead to significant benefits. By reducing inventories and handling costs through lean techniques, as well as transferring more production from Japan to North America, Toyota could offer high-quality service and crash parts to its dealers at the lowest cost. This would eliminate the need for special promotions to lower prices and boost sales, which were costly and unpredictable due to the production of large amounts of parts in advance without knowing the actual demand. These promotions caused fluctuations in orders to suppliers and excess inventory in the distribution channel. To address this issue, Toyota focused on "level selling" by keeping prices constant and producing replacement parts at the exact rate they were being sold. However, convincing dealers to adopt this approach was challenging, as they were accustomed to batch-and-queue thinking. Despite the challenges, Toyota saw the potential advantages of applying pull to the entire value stream, from the dealer service bay to second-tier suppliers like bumper chromers. The inefficiencies observed at car dealerships, such as vast lots of unsold cars and promotions on service and parts, stem from various factors. Mass-production car manufacturers like Chrysler create excess inventory to cater to impulse purchasers, leading to vast seas of cars on dealer lots. This practice contrasts with Toyota's lean production system, which can build and deliver cars to order in about a week, reducing the need for excess inventory. Additionally, dealers and customers alike are accustomed to the culture of bargaining and seeking sales, contributing to the perpetuation of this system. Changing this mentality is challenging but necessary for implementing more efficient processes. At Sloane Toyota near Philadelphia in 1994, the parts storage area was disorganized and inefficient, with a three-month supply of parts creating a $580,000 inventory. When cars came in for repairs, technicians often faced delays in obtaining necessary parts due to erratic workload and misplaced inventory. In 1995, Sloane Toyota joined Toyota's push to implement a pull system in parts distribution. By reorganizing the storage area and reducing bin sizes, Sloane increased part numbers on hand by 25% while cutting storage space in half and reducing inventory to $290,000. This freed up cash to add service bays without capital investment. With improved efficiency, more cars received same-day service, reducing the need for loaner vehicles, and customer satisfaction increased as repairs were completed promptly and at lower cost. Bob Scott was able to get his truck's bumper replaced more efficiently thanks to these changes. By the end of 1996, Toyota's new pull system will be fully implemented throughout North America, transforming the service value stream. Customer requests in Toyota dealer service bays will trigger a series of replenishment loops, pulling parts all the way back to steel blanks. While Toyota will still use computerized macroforecasts for capacity planning, dayto-day part replenishment will occur in a "sell one; buy one" or "ship one; make one" fashion. For instance, let's follow the example of a bumper through the value stream. Before lean techniques were applied, the elapsed time from steel blanks to the finished bumper was extensive. However, by the end of 1995, this time had been reduced to four months, with improvements in lead times at each stage of production and distribution. By the end of 1996, elapsed time is expected to decrease further to about 2.5 months as inventory levels shrink in response to faster resupply times. These improvements have been achieved without significant capital investment. Instead, modifications were made by production workers as part of kaizen activities, and elaborate MRP systems are no longer necessary. This results in substantial cost savings and increased efficiency throughout the value stream. The savings achieved so far represent just the beginning of the journey towards perfection for Sloane Toyota, Toyota Motor Sales, Bumper Works, and Chrome Craft. They are now working as a lean enterprise under Toyota's guidance, committed to continuously reducing elapsed time and costs for service and crash parts. Quality is expected to improve naturally as flow and pull processes are optimized. One approach involves extending the smooth-flowing value stream all the way to raw materials by addressing batch-andqueue thinking in upstream suppliers. At the customer end, efforts may be made to schedule service requirements in advance to predict parts needs accurately. Toyota pursued a similar approach in Japan between 1982 and 1990, reorganizing its service and crash parts business and establishing Local Distribution Centers (LDCs) jointly owned with dealers. These LDCs now carry only a three-day supply of essential parts, enabling same-day repairs without the need for express freight. Customers schedule service in advance, allowing parts to be ordered precisely as needed. While some aspects of this system may be more feasible in regions with high population density, the efficiency gains and improved customer service are significant. As stock levels decrease and replenishment orders become smaller and more frequent, Parts Distribution Centers (PDCs) will evolve into cross-docking points, facilitating faster delivery to dealers. While the vision of making parts at the dealership as needed may be a distant possibility, the improvements made by Toyota in Japan and the United States are available for adoption by service businesses across industries today. These advancements represent a significant leap compared to current practices and offer opportunities for remarkable efficiency gains. The introduction of pull systems in the Toyota service value stream raises profound questions about the nature of CHAOS in product markets and the macroeconomy. While chaos theory has influenced business thinking, particularly regarding reconfigurable corporations and chaos management, it may misinterpret the dynamics of customer-producer relations. In many industrial sectors, product markets exhibit relative stability and predictability, with technology trajectories and end- 13 use demand being largely steady. However, perceived marketplace chaos often arises from self-induced factors such as long lead times and promotional activities. One proposed solution is the creation of learning organizations to reflect on and respond to these phenomena. However, an alternative proposal suggests eliminating lead times and inventories to ensure demand is instantly reflected in new supply. This approach aims to eliminate the mismatch between supply and demand, reducing chaos in the process and revealing the underlying stability of demand patterns. If we can get rid of making stuff ahead of time and storing it, we think it'll help calm down the usual ups and downs in the economy. Economists usually say that when things slow down in the economy, it's because people and companies are using up all the extra stuff they made when times were good. And when things pick up, it's because they're making a bunch of new stuff in anticipation of higher prices or more sales, but those big sales never happen as expected. Despite trying to control it, governments haven't been able to smooth out these ups and downs in the economy since World War II. But we can't really test our idea yet because, even though Japan has been doing this lean thinking stuff for a while and places like the US and Europe have known about JIT for years, we still haven't seen much change in how much stuff gets made ahead of time and stored, at least not enough to make a big difference. So, we're still waiting to see if getting rid of all that extra stuff will really help calm things down. PERFECTION. There are diminishing returns to any type of effort. Keizen activities are not free, and perfection (menaing the complete elimination of Muda) is surely impossible. Every enterprise needs both Continuous Radical Approach and Incremental Improvement Approach to pursua Perfection. Every step in a value stream can be improved in isolation to good effect. If you are spending significant amounts of capital to improve specific activites, you are usually pursuing perfection the wrong way. Going further, most value strams can be radically improved as a whole if the right mechanism for analysis can be put in place. However, to effectively pursue both radical and incremental improvement, two final Lean Techniques are needed. First, in order to form a view in thierr minds of what perfection would be, value stream managers need to apply the four Lean Principles of value specification, value stream ideantification, flow, and pull. Then, value stream managers need to decide which forms of Muda to attack first, by means of policy deployment. At every step we’ve noticed the need for manager to leand to see: to see the value stream, to see the flow of value, to see value bring pulled by the customer. The final form of seeing is to bring perfection into clear view so the objective of improvement is visible and real to the whole enterprise. Perfection is like infinity. Trying to envision it and to get there is actually impossible, but the effort to do so provide inspiration and direction essential to make progress along the path. One of the most important things to envision is the type of product designs and operating technologies needed to take the next steps along the path. On eof the greatest impediments to rapid progress is the inappropriateness of most exiting processing technology to the needs of Lean Enterprise. A clear sense of direction – the knowledge that products must be manufactures more flexibly in smaller volumes in continuous flow – provides critical guidance to technologists in the functions developing designs and tools. In addition to forming a picture of perfection with the appropriate technologies, managers need to set a stringent timetable for steps along the path. Firms which never start down the path because of a lack of vision obviously fail. Sadly, we've watched other firms set off full of vision, energy, and high hopes, but make very little progress because they went tearing off after perfection in a thousand directions and never had the resources to get very far along any path. What's needed instead is to form a vision, select the two or three most important steps to get you there, and defer the other steps until later. Its not that these will never be tackled, only that the general principle of doing one thing at a time and working on it continuously until completion applies to improvement activities with the same force as it applies to design, order-taking, and production activities. What’s critically needed is the last lean technique of policy deployment. The idea is for top management to agree on a few simple goals for transitioning from mass to lean, to select a few projects to achieve these goals, to designate the people and resources for getting the projects done, and, finally, to establish numerical improvement targets to be achieved by a given point in time. The targets would usually set numerical improvement goals and time frames for the projects. Most organizations trying to do this find it easiest to construct an annual Policy Deployment Matrix which summarizes the goals, the projects for the year, and the targets for these projects so everyone in the entire organization can see them. In doing this, it is essential 14 to openly discuss the amount of resources available in relation to the targets so that everyine agrees as the process begins that is is acutally doable. Once the specific projects are agreed on, it is essential to consult with the project teams about th eamount of resources and rime available to ensure that the projects are realistic. The teams are collectively responsible for getting the job done and must have both the authority and resources from the outset. As the concept of making a dramatic transition begins to take hold, we often observe that everyone in an organization wants to get involved and that the number of projects tends to multiply. This is exhilarating, but is actually the danger signal that too much is being taken on. The most successful firms have learned how to “deselect” projects, despite the enthusiasm of parts of the organization, in order to bring the number of projects into line with the available resources. This is the critical final step before launching th elean crusade. The process of introducing lean principles into organizations often faces a paradox. While the philosophy behind lean thinking promotes openness, transparency, and teamwork, the actual change is usually driven by an outsider known as the CHANGE AGENT. This person often disrupts traditional practices, sometimes in times of crisis, and is perceived as a kind of "tyrant" imposing new ways of working. However, not all tyrants are the same. Successful change agents are seen as promoting ideas that benefit everyone involved, while unsuccessful ones are viewed as self-serving or disconnected from the human aspects of the transition. Lean systems thrive when everyone believes they are fair and address human concerns. This book encourages readers to embrace the role of change agent, but only if they approach it with benevolence and a genuine commitment to improvement. LEAN PRODUCTION TECHNIQUES. First Pillar: JUST IN TIME. LAYOUT: Conventional functional layouts create pipeline inventory, delays, movement costs and other forms of waste. In the JIT approach: Operations are arranged to achieve a logical flow (e.g. cell, line). Equipment is close together to reduce cost of movement. Often “U” shaped to increase visibility and teamwork. The emphasis is on semplicity, flow, visibility and morale. TAKT TIME is the consumption rate of the customer. It is the reference to determine the production rate. 15 How to implement the Flow? The value should flow smoothly. The aim: 1. . How? Balancing the line: SMED (Changeover / Set-Up Reduction): Single minute Exchange Die. It is about increasing productivity by decreasing the time from the last good product to the first good product. It does not necessarily mean that every changeover should take only one minute, but it emphasizes the objective of reducing the setup time to the lowest possible. - - 2. - 3. - How to implement SMED? Measure and analyze changeover activities. Separate external and internal activities. o External activities are performed while the process is continuing. o Internal activities are performed while the process is stopped. Primary goal is to change all internal activities to external ones. o Pre-prepare activities or equipment. o Make the changeover process flexible. o Speed up the required changes of equipment. Practice changeover routines. The conventional Western Approach is to purchase large machines to get economies of scale. These often have long, complex set-ups, and make big batches, quickly creating waste. Using several SMALL MACHINES allows: Simultaneous processing. Easy to move (layout). Quick set-up. Planned maintenance easier (more robust). PULL LOGIC – the use of Supermarkets. Each stage of the process has to produce a good only if an information from downstream stage/customer triggers the production. Request is based on consumption of a controlled inventory that is called “Supermarket” located between the processes. If the downstream process does not consume, the upstream process does not produce, even if this does not match the forecast. 16 - PULL LOGIC – Kanban. Reversal of traditional push system where material is pushed according to a schedule (MRP). Products are pulled through the production process by requests called KANBAN CARDS. Kanban is a simple way to make a Pull System working, i.e., a system to start production (or purchasing) of a component only when required by the demand. When it is required by demand, Kanban is sent from one production stage to the upstream stage to signal components are needed. Move Kanban signals the required delivery of parts to the next stage of production. It is usually associated with a “single card Kanban” system. Second Pillar: JIDOKA. - Jidoka enables operations to build-in quality at each process and to separate man and machines for more efficient work. It helps minimize defects before they reach the customer. It is the ability for machines to be self-dependent and error proof without any human interaction. It is also called “Autonomation”, meaning “Autonomation with Human Intelligence”. - It is made up by 3 elements: Separate human from machine work. - Machines detect/prevent abnormalities (Poka Yoke). “Stop the Line” authority in operation (Andon). 17 ANDON is an information tool which provides instant, visible and audible warning to the Operations Team that there is an abnormality within that area. Commonly lights to signal production line status: Red: line stopped. Yellow: call for help. Green: all normal. Andon signals require immediate attention. POKA YOKE is a fool proofs operations that reduce/eliminate mistakes in processes. It helps operators to avoid mistakes in their work caused by choosing the wrong part, leaving out a part, installing a part backwords, etc. Poka Yoke devices are usually quite simple, inexpensive, and either inform the operator that a mistake is about to be made or prevent the mistake altogether. The philosophy encourages a proactive approach to quality by addressing potential issues before they lead to defects or mistakes. Third Pillar: STABILITY. Work must be standardized: Standard work defines the agreed upon best known method to produce an item using the available equipment, tools, propple and material (SOP : Standard Operating Procedures). Better quality and lower costs. The equipment, tools, and workplace must be highly reliable: 5S. 18 TPM – Total Productive Maintenance. Kaizen: Ohno said: “There is no keizen without standardization”. Keizen techniques allow to overcome the boundaries of standard work by asking “how can we deviate from our existing procedures to imrpove our performance by setting new standard?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVceh3MOsNc 1. - The 5S: SORT (Seiri): Eliminate what is not needed and keep what is needed. STRAIGHTEN (Seiton): Position things in such a way that htey can be easily reached whenever they are needed. SHINE (Seiso): Keep things clean and tidy; no refuse or dirt in the work area. STANDARDIZE (Seiketsu): Maintain cleanliness and order – perpetual neatness. SUSTAIN (Shitsuke): Develop a commitment and pride in keeping to standards. You cannot see wastes clearly when the workplace is in disarray. Cleaning and organizing the workplace helps to uncover wastes. 5s creates ownership of workplace. The real goal of 5s is Standardization. The goal is to improve companies’ performances, employees will perform better, with less stress and produce higher quality when the work area is clearly layout and the processes are clearly defined. 2. - - TPM – Total Productive Maintenance. It aims at optimizing the effectiveness of manifacturing equipment and tooling. It is not a reactive maintenance technique. It is carried out by all employees trhough small group activities (autonomous maintenance). It includes daily routines of maintenance (claning, inspection, oiling, and re-tightening) to prevent failures and to prolong the life cycle of equipment (preventing maintenance). Maintenance personnel’s role changes: Training operators in relevant maintenance skills. Long-term planned maintenance. Condition monitoring. Designing or specifying equipment that does not break down and easy to maintain (maintenance prevention). 19 Fare libro fino a pag. 98. Il libro si riferisce al capitolo dei Lean Principles. 20