Fundamentals of Finance Financial institutions and markets 2016 -- Massey University Press

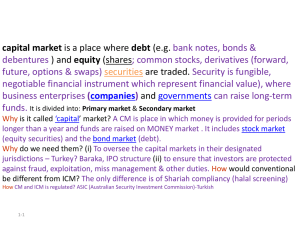

advertisement