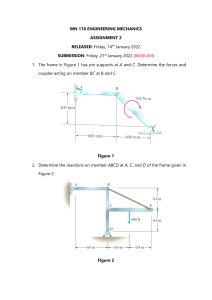

Introduction to taxation

and calculation of net tax

payable

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

1

Gross

income

–

Exempt

income

–

Deductions

=

Taxable

income

Tax per table

–

Rebate

=

Normal

tax liability

–

Prepaid

taxes

Tax liability

=

Net tax due/

(refundable)

Page

1.1

Introduction .........................................................................................................

2

1.2

Taxation in perspective ......................................................................................

1.2.1 Types of taxation ....................................................................................

1.2.2 Classification of taxes ............................................................................

1.2.3 Criteria of a good tax system................................................................

2

2

2

3

1.3

The budget process .............................................................................................

1.3.1 Medium-term expenditure framework ..............................................

1.3.2 The national budget...............................................................................

1.3.3 The Income Tax Act 58 of 1962 (the Act) ............................................

4

4

4

6

1.4

Calculation of taxable income (section 5).........................................................

7

1.5

Calculation of final normal tax liability ...........................................................

1.5.1 Year or period of assessment (section 1) .............................................

1.5.2 Normal tax (section 5) ...........................................................................

1.5.3 Normal tax rebates for natural persons (section 6) ...........................

1.5.4 Medical scheme fees tax credit (MTC) (section 6A) ..........................

1.5.5 Additional medical expenses tax credit (AMTC) (section 6B) .........

1.5.6 Rebate in respect of foreign taxes on income (section 6quat) ...........

1.5.7 Prepaid taxes ..........................................................................................

12

13

14

15

17

19

23

23

1

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:24 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.6

1.7

1.8

1.9

1.1–1.2

Tax returns, assessments and objections ..........................................................

Tax practitioners ..................................................................................................

Summary ..............................................................................................................

Examination preparation ...................................................................................

Page

24

25

26

27

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

1.1 Introduction

Most people who enter the workplace are amazed to see how much tax is deducted

from their monthly salary. Most people’s first reaction is: ‘There must be a mistake; I

am paying too much tax.’ After consultation with the salary department, it is usually

confirmed that the correct amount was deducted. The reality of tax is something that

most people have to face whether they are employed or operating their own business.

Critical questions

When dealing with taxation a person is normally confronted with the following questions:

• What determines the tax rate?

• Do the taxation rules change every year?

• Which types of taxes are levied in the Republic?

• What does the government do with the tax levied?

• How is a person’s taxable income for the year calculated?

• How does a person know how much tax they should pay?

• How does the government collect the tax that is due?

1.2 Taxation in perspective

Taxes are levied to enable the government to provide services to the people. Another

view is that taxes are contributions to the State for the ultimate benefit of all who

enjoy the privileges and protection offered by the State.

1.2.1 Types of taxation

In South Africa we pay a variety of taxes of which the main types are income tax,

(which includes capital gains tax), value-added tax (VAT), excise and customs duties

and a whole range of other taxes such as transfer duty and local authority taxes.

South Africans also pay donations tax and estate duty (which tax the transfer of

wealth), securities transfer tax on shares and local property rates.

1.2.2 Classification of taxes

There are a number of ways to classify taxes ranging from the tax calculation method

used, to identifying the person who is ultimately responsible for paying the tax.

Taxes are classified according to a number of different factors.

2

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:31 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

1.2

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

Based on what the various taxes are levied on

• Income Tax on income earned, for example normal tax levied on taxable income.

• Consumption Taxes on the sale or use of goods or services, for example VAT,

excise duty on domestic consumption, and customs duty and import tariffs on foreign trade. These taxes take the form of price increases and affect the consumers.

• Wealth Taxes on the ownership of assets or capital gains made on the sale of

property, for example capital gains tax, estate duty, donations tax and local authority taxes.

• Other Taxes that are levied on specific business transactions, for example stamp

duty, transfer duty and securities transfer tax.

The method used to calculate the tax

• Proportional tax Tax is levied at a fixed rate on the amount of income earned,

for example income tax on companies is levied at a fixed rate of 28% of taxable

income.

• Progressive tax The rate that is used to calculate the amount of tax is determined

by the person’s income. The higher a person’s income, the higher the tax rate that

is used to calculate the tax, for example income tax levied on natural persons.

• Regressive tax The tax rate decreases with the increase of a person’s income. No

such form of tax exists in South Africa.

The person who has the responsibility of paying the tax

• Direct tax The impact and incidence of tax falls on the same person (the person on

whom the tax is levied bears the impact, while the person who ultimately pays the

tax, bears the incidence). Income tax and capital gains tax are therefore direct taxes.

• Indirect tax The seller bears the impact of the tax, while the consumer ultimately

pays the tax. VAT is an example of an indirect tax.

1.2.3 Criteria of a good tax system

As early as 1776, Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, recognised that the levying of

taxation should comply with certain basic criteria or norms and proposed the following four canons (or principles) of taxation:

• Equity The subjects of every state ought to contribute, almost in proportion to

their abilities, towards the support of the government, that is to say in proportion

to the benefits which they enjoy under the protection of the state.

• Certainty The tax that every individual is bound to pay should be certain and not

arbitrary. This means that the time and manner of payment, and the amount to be

paid should be clear and plain to the contributor and to every other person.

• Convenience Every tax should be levied at the time or in the manner most convenient for the contributor to pay it.

• Economy Every tax should be such that the contributor pays the minimal additional cost for administration and in submission costs beyond its actual tax, but it

must still be sufficient to provide the treasury of the State with the amount it

requires.

3

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:31 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

1.2

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Based on what the various taxes are levied on

• Income Tax on income earned, for example normal tax levied on taxable income.

• Consumption Taxes on the sale or use of goods or services, for example VAT,

excise duty on domestic consumption, and customs duty and import tariffs on foreign trade. These taxes take the form of price increases and affect the consumers.

• Wealth Taxes on the ownership of assets or capital gains made on the sale of

property, for example capital gains tax, estate duty, donations tax and local authority taxes.

• Other Taxes that are levied on specific business transactions, for example stamp

duty, transfer duty and securities transfer tax.

The method used to calculate the tax

• Proportional tax Tax is levied at a fixed rate on the amount of income earned,

for example income tax on companies is levied at a fixed rate of 28% of taxable

income.

• Progressive tax The rate that is used to calculate the amount of tax is determined

by the person’s income. The higher a person’s income, the higher the tax rate that

is used to calculate the tax, for example income tax levied on natural persons.

• Regressive tax The tax rate decreases with the increase of a person’s income. No

such form of tax exists in South Africa.

The person who has the responsibility of paying the tax

• Direct tax The impact and incidence of tax falls on the same person (the person on

whom the tax is levied bears the impact, while the person who ultimately pays the

tax, bears the incidence). Income tax and capital gains tax are therefore direct taxes.

• Indirect tax The seller bears the impact of the tax, while the consumer ultimately

pays the tax. VAT is an example of an indirect tax.

1.2.3 Criteria of a good tax system

As early as 1776, Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, recognised that the levying of

taxation should comply with certain basic criteria or norms and proposed the following four canons (or principles) of taxation:

• Equity The subjects of every state ought to contribute, almost in proportion to

their abilities, towards the support of the government, that is to say in proportion

to the benefits which they enjoy under the protection of the state.

• Certainty The tax that every individual is bound to pay should be certain and not

arbitrary. This means that the time and manner of payment, and the amount to be

paid should be clear and plain to the contributor and to every other person.

• Convenience Every tax should be levied at the time or in the manner most convenient for the contributor to pay it.

• Economy Every tax should be such that the contributor pays the minimal additional cost for administration and in submission costs beyond its actual tax, but it

must still be sufficient to provide the treasury of the State with the amount it

requires.

3

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:28 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.2–1.3

In the modern context, these principles must also include the broader principles of

social justice.

1.3 The budget process

The tax rate to be used for a specific year of assessment is determined after the budget

process has been completed and the government knows how much revenue they

require.

1.3.1 Medium-term expenditure framework

The government’s budgeting process starts with the preparation of the medium-term

expenditure framework document. This document sets out the expected expenditure of

the different government departments and the expected revenue for the next three years.

The document is prepared to assist in the government’s main objectives, as set in the

National Development Plan. The expenditure framework also seeks to implement

certain broad economic policy objectives.

These macro-economic policies include –

• the maintenance of full-time employment;

• the achievement of a high rate of economic growth;

• the maintenance of price stability (that is to say the prevention of inflation); and

• the maintenance of external equilibrium (that is to say the maintenance of a

favourable balance of payments and a stable exchange rate).

The three-year framework and the budget process form part of the fiscal policy that

can be used to achieve the macro-economic goals. Fiscal policy influences the total

demand in the household’s economy. An increase in government expenditure or a

decrease in taxes will increase disposable income and therefore demand. This will lead

to increased supply (goods being made) and therefore an increase in employment (or a

decrease in unemployment). Fiscal policy is controlled by the National Treasury.

The second measure that can be used to achieve the macro-economic goals is monetary policy. Monetary policy is the action by the monetary authority (South African

Reserve Bank) aimed at influencing the use of money and credit; this is done through

changes in interest rates. The Reserve Bank controls the interest rates and therefore

the monetary policy. It is important to note that taxation measures do not form part

of the monetary policy but of the fiscal policy.

1.3.2 The national budget

Each year during February, the Minister of Finance presents his budget proposals in

the form of a ‘budget speech’ to Parliament. It has become customary for the budget

speech to start with a short review of the economic, political, social and other circumstances that have had an effect on the budget proposals.

In the second part of his speech, the Minister discusses the most important items of

estimated state expenditure, the reasons for these items of expenditure and the policy

objectives the State wishes to achieve. He also discusses the sources of the revenue to

be used in defraying this expenditure and, as taxes form the major proportion of this

revenue, the details of proposed tax changes.

4

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:28 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

1.3

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

The third part of the speech refers to the budget documents tabled at the session.

These documents include –

• the estimate of expenditure to be defrayed from the National Revenue Fund;

• the estimate of income to be received;

• the statistical/economic survey;

• the tax proposals;

• comparative figures of income; and

• any other relevant documents.

These documents give an indication of how the income received during the year will

be spent by the government. Table 1.1 summarises budgeted government expenditure for the 2021/2022 fiscal year.

Table 1.1: Budgeted government expenditure (source: Budget 2021)

Percentage

of expenditure as

budgeted

Type of expenditure

Social Development

20,1%

Learning and culture

18,87%

Health

12,0%

Debt-service costs

11,4%

Peace and Security

10,7%

Community Development

10,3%

Economic Development

9,3%

General public services

3,1%

Payments for financial assets

4,3%

The documents provided to Parliament also indicate how the income will be gathered.

Table 1.2 provides a summary of government’s planned income for the 2021/2022

fiscal year before the effects of lockdown and Covid-19 were taken into account.

Table 1.2: Sources of government income (source: 2021 Budget Highlights)

Amount received

R‘billion

Type of tax

Percentage

of income

Personal income tax

516.0

37,8%

VAT

370.2

27,1%

Corporate income tax

213.1

15,6%

83.1

6,1%

Fuel levies

Customs and excise duties

100.5

7,4%

Other

82.2

6,0%

Total

1 365.1

100,0%

5

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:34 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.3

From the table above it is clear that the government receives most of its income from

income tax levied on individuals and companies, and VAT. Once a year the National

Treasury and SARS publish tax statistics, giving information about how and where

taxes were collected.

Tax statistics

According to the 2020 tax statistics South Africa had 20 million registered individual

taxpayers. Some interesting facts are

• 40,9% of assessed taxpayers were registered in Gauteng.

• 27,0% of assessed taxpayers were 35 to 44 years old.

• 45,8% of assessed taxpayers were female.

• Travel allowances were the largest allowance for individuals: 26,3% of total allowances

assessed.

• Retirement fund contributions paid on behalf of employees was the largest fringe

benefit (50,8% of the total fringe benefits assessed).

• Contributions to retirement funding was the largest deduction (83,4% of all deductions

granted).

1.3.3 The Income Tax Act 58 of 1962 (the Act)

After debate by Parliament and referral to the Standing Committee on Finance (and

possibly to other committees), the draft taxation bills are presented to the State President for signature and are finally promulgated as an Act of Parliament by publication

in the Government Gazette. The result of this is that these Acts now become part of the

main Income Tax Act and this results in a change to the Act.

When calculating your tax liability or when advising a client about their tax affairs, it

is critical to ensure that you are referring to the correct version of the Act. If you use a

previous or later version of the Act, the calculation or advice that you give might be

incorrect or out of date, resulting in negative tax and financial implications for your

client and even for yourself.

Interpretation rules If the language of the Act provided for absolute certainty, there

would be no necessity for interpretation. Unfortunately this is not the case and the

many court decisions on tax matters are testimony to the need for interpretation. The

circumstances and situations giving rise to income and expenses are also often very

complex, making the application of the provisions of the Act difficult and uncertain.

Where a dispute relating to the application of the Act to a particular case arises

between the revenue authorities and a taxpayer, the parties frequently have to rely on

the courts to give a decision.

The interpretation of law is a very complex field of study and for the purposes of this

book, it is sufficient to take note of a few of the more important rules of interpretation. The need for interpretation will arise only where a provision in the Act is not

clear.

• Hardship is no criterion Even if a certain provision in the Act leads to hardship

for the taxpayer, provided the language of the section is clear, the fact that it gives

rise to hardship cannot be taken into consideration.

6

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:34 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

1.3–1.4

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

• The literal meaning must be applied If the literal meaning is clear, it must be

applied even if it may give rise to apparently unfair results.

• The intention of the legislature The intention of the legislator must be applied. A

governing rule in interpretation is, in general, to try to ascertain the intention of the

legislature from a study of the provision in question.

• The contra fiscum rule The benefit of the doubt must be given to the person

sought to be charged, except in cases where a provision in the Act is designed to

prevent tax avoidance. In these cases it should be interpreted in such a way that it

will prevent the mischief against which the section is directed. The rule can be

summarised as follows: the benefit of the doubt would therefore be given to the

taxpayer, except where tax avoidance is involved.

A distinction must be drawn between interpretation by the courts and a practice

adopted by the South African Revenue Service (SARS). Where the wording in the Act

isn’t clear, the courts cannot take note of the SARS practice or base their interpretation on the practice. Instead, the court must apply the rules of interpretation. Apart

from interpretation, the practice of SARS plays an important role in the administration of the Act. ‘Interpretation Notes’ are issued from time to time to inform taxpayers about some practices that apply.

1.4 Calculation of taxable income (section 5)

Section 5(1) of the Act makes provision for the payment of income tax (which is

referred to as normal tax) on the taxable income received by or accrued to or in

favour of a person during the year of assessment.

In order to determine how much tax a person should pay, that person’s taxable

income must first be established. The Act has a number of definitions that must be

used to determine a person’s taxable income. Section 1 of the Act provides the following definition of taxable income:

[T]he aggregate of –

(a) the amount remaining after deducting from the income of any person all the

amounts allowed under Part I of Chapter II to be deducted from or set off against

such income; and

(b) all amounts to be included or deemed to be included in the taxable income of any

person in terms of this Act.

It is clear from the above that in order to calculate a person’s taxable income, the

income for the year and the expenditure allowed for the year need to be determined.

The expenditure is set out in Part I of Chapter II of the Act. The amount of the

expenditure that is allowed as a deduction will depend on the kind of expenditure

and the date of the expenditure. These rules are dealt with in later chapters. The term

‘income’ is also defined in section 1 of the Act, which reads as follows:

[T]he amount remaining of the gross income of any person . . . after deducting therefrom any amounts exempt from normal tax . . .

A list of income that is exempt from tax is provided in section 10 of the Act and is

discussed in chapter 3.

7

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:35 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.4

Examples of exempt income are dividends and interest received. For example, local

dividends received are exempt from income tax but only a portion of foreign dividends are exempt from tax. Interest received by a natural person will also be exempt

but limited to a maximum of R23 800 for persons under 65 years of age and R34 500

for persons 65 years of age or older on the last day of the year of assessment. All

income (for example interest, dividends and capital gains) received on a tax free

investment is exempt from income tax. Only accounts that meet specific criteria are

classified as tax free investments, these investments must be identified as such in the

name of the investment.

REMEMBER

• Exempt income is deducted from gross income; therefore, an amount can only be exempt

income if it is already included in gross income.

The next step is to determine which amounts are included in gross income. The Act

provides a definition of ‘gross income’ in section 1:

Gross income in relation to a year or period of assessment –

(i) in the case of a resident, the total amount, in cash or otherwise, received by or

accrued to or in favour of such resident; or

(ii) in the case of a person other than a resident the total amount, in cash or otherwise, received by or accrued to or in favour of such person from a source within

the Republic,

during such year or period of assessment, excluding receipts or accruals of a capital

nature, but including . . . amounts . . . as described hereunder . . .

The gross income definition can be divided into three components:

• the general rule for residents of South Africa;

• the general rule for non-residents of South Africa; and

• amounts specifically included in a person’s gross income.

A salary received is an example of an amount to be included in gross income in terms

of the general rule as it complies with all the requirements of the definition. These

requirements are discussed in chapter 2.

Remember that it is not required that a person must receive an amount before it is

included in gross income, that is to say where an amount accrues to the taxpayer, it

will also be taxable even though they have not physically received it. For example, if

a person invests in a unit trust (also known as a collective investment scheme) and

elects to reinvest the annual interest and dividend earned, they will never receive

these amounts in cash. The income is however reinvested for their benefit and is

therefore included in their gross income as it accrues to them.

As from 1 October 2001 all capital gains are also subject to normal tax. The taxable

portion of the capital gain must be added to the taxable income from the revenue

activities to calculate the total taxable income for the year. The calculation of the

taxable capital gain is discussed in chapter 13.

8

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:35 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.4

Framework for the calculation of taxable income

The definitions discussed above provide a fixed structure that should be used to calculate taxable income. This sequence may be set out as in the following framework:

R

Gross income (as defined in section 1)

Less:

Exempt income (sections 10, 10A and 12T)

Income (as defined in section 1)

Deductions (section 11 – but see below; subject to section 23(m) and

assessed loss (sections 20 and 20A))

Taxable portion of allowances (section 8 – such as travel and subsistence

allowances)

Less:

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Add:

xxx

(xxx)

xxx

(xxx)

xxx

Add:

Taxable income before taxable capital gain

Taxable capital gain (section 26A)

Less:

Taxable income before retirement fund deduction

Retirement fund deduction (section 11F)

xxx

(xxx)

Less:

Taxable income before donations

Donations deduction (section 18A)

xxx

(xxx)

Taxable income (as defined in section 1)

xxx

xxx

xxx

Calculating taxable income

Step 1:

Identify amounts that comply with the ‘gross income’ definition (chapter 2).

Step 2:

Identify amounts included in gross income that are exempt in terms of

the Act (chapter 3).

Step 3:

Identify amounts that can be deducted for tax purposes (chapters 4

and 5).

Step 4:

Calculate the taxable income (before taxable capital gain and donations) by deducting the exempt income (Step 2) and the deductions

(Step 3) from the gross income (Step 1).

Step 5:

Calculate the taxable capital gain (chapter 13).

Step 6:

Calculate the total taxable income by adding the taxable income (before

taxable capital gain and donations) (Step 4) to the taxable capital

gain (Step 5) and, thereafter, deducting the allowable deductions for

donations.

9

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:32 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.4

REMEMBER

• Exempt income can only be exempted if it has been included in gross income.

• Taxable income may be a negative amount which is called ‘an assessed loss’.

• A person is anybody who receives ‘income’. Therefore even a minor (person younger

than 18) who receives income is a taxpayer and pays tax in their own name. In some

cases the parent of a minor can be taxed on the income of the child, but then specific

requirements must be met.

Example 1.1

Robert Roberts is a 40-year-old resident of South Africa. During the current year of

assessment he received a salary of R300 000. He owns shares in Sam Ltd (a South African

company) and received a dividend of R4 000 during the current year. Robert contributed

R6 000 to his employer’s pension fund (the total amount is deductible for income tax purposes). Robert made a taxable capital gain of R1 000.

You are required to calculate Robert’s taxable income for the current year of assessment.

Solution 1.1

R

Gross income

Salary received

Dividends received

300 000

4 000

304 000

Less: Exempt income

Dividends received

(4 000)

300 000

1 000

301 000

Income

Add: Taxable capital gains

Less: Deductions

Retirement fund contributions

(6 000)

295 000

Taxable income

1.

Why are the dividends received included in gross income if they are

an exempt income?

2.

Must taxable capital gains be included last or can it be added to

gross income?

Married in community of property

Income received or accrued from carrying on a trade (excluding the letting of fixed

property) is taxed in the hands of the spouse who is carrying on the trade, for

10

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:32 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.4

example if the wife earns a salary or profit from business activities, she will be taxed

on the amount earned. On the other hand, if a couple is married in community of

property and either of them earns any passive income (that is to say income other

than trade income, for example dividend or interest income), it is deemed to have

accrued equally to each spouse. Where a spouse’s income is deemed to be the income

of the other spouse, the deduction or allowance relating to that income is allowed in

the same proportion as that in which the income is taxed.

REMEMBER

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

• Income derived from a trade will only be taxed in the hands of the spouse who is carrying on the trade.

• Income that will be split where spouses are married in community of property therefore

includes –

– local and foreign interest;

– local and foreign dividends;

– income from letting of fixed property.

• Income that will NOT be split where spouses are married in community of property

therefore include –

– a benefit paid by a pension, provident or retirement annuity fund;

– income specifically excluded from the joint estate; and

– a purchased annuity.

Calculating taxable income – married in community of property

Step 1:

Add both spouses’ passive income together to get a total passive

income, for example total interest received.

Step 2:

Divide the total passive income equally between the two spouses.

Include in each spouse’s calculation half of the total passive income,

and add it to the individual’s gross income.

Example 1.2

John (59 years old) and Jane (66 years old) Naidoo are married in community of property.

John received a salary of R150 000 during the current year of assessment. John also

received R60 000 interest on his savings account. Jane did not receive any income during

the current year of assessment.

You are required to calculate John and Jane’s taxable income for the current year of

assessment.

11

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:38 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.4–1.5

Solution 1.2

John

Gross income

Salary received

Interest received (Note)

R

150 000

30 000

Less: Interest exemption – R23 800 maximum

180 000

(23 800)

Taxable income

156 200

Jane

Gross income

Interest received (Note)

Less Interest exemption – R34 500 maximum but limited to amount received

30 000

(30 000)

Taxable income

nil

Note

As John and Jane are married in community of property, it is deemed that the interest was

received in equal shares by each spouse. Therefore they each include R60 000 / 2 = R30 000

in their gross income.

1.

Why is R30 000 interest exempt for Jane and only R23 800 for John?

2.

As Jane is over 65 years old, why did she not get an interest exemption of R34 500?

REMEMBER

• Where persons are married in community of property, each spouse qualifies for their

full interest exemption on half of the gross interest received. An exemption can never

exceed the amount received.

1.5 Calculation of final normal tax liability

After a person’s taxable income has been determined this amount is used to calculate

their normal tax liability for a year or period of assessment.

Normal tax calculated based on the tax tables

Less:

Annual rebates (section 6)

Less:

Medical tax credits (sections 6A and 6B)

Less:

Add:

Normal tax liability for the year

PAYE and provisional tax (prepaid taxes)

Normal tax due by or to the taxpayer

Withholding taxes

Final tax liability of natural person

12

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:38 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

R

xxx

(xxx)

(xxx)

xxx

(xxx)

xxx

xxx

xxx

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.5

Calculating final normal tax liability

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Steps 1–6:

Calculate the total taxable income for the year of assessment as discussed previously.

Step 7:

Calculate normal tax by using the tax table (paragraph 1.5.2).

Step 8:

Determine the age of the taxpayer on 28/29 February of the current

year of assessment. Determine whether the taxpayer qualifies for the

full rebate for the current year of assessment, if not pro rata the

rebate (paragraph 1.5.3).

Step 9:

Calculate the medical scheme fees tax credit and the additional

medical expenses tax credit (paragraphs 1.5.4 and 1.5.5).

Step 10:

Calculate tax credits for specific transactions (if any) (paragraph 1.5.6).

Step 11:

Calculate normal tax liability: normal tax for the year (Step 7)

minus

• rebates (Step 8);

• medical credits (Step 9);

• tax credits for specific transactions (Step 10).

Step 12:

Calculate prepaid taxes (PAYE and provisional tax) (paragraph 1.5.7).

Step 13:

Calculate final tax liability

= Normal tax liability (Step 11) minus prepaid taxes (Step 12).

1.5.1 Year or period of assessment (section 1)

The following guidelines can be used to determine the year or period of assessment:

• In the case of a person other than a company, the year of assessment ends on 28 or

29 February.

• When a taxpayer dies, the period of assessment will run from 1 March up to and

including the date of death.

• When a baby is born and they are entitled to income, their year of assessment is

from the date of birth (including this day) until the end of February.

• A taxpayer who is declared insolvent will have a period of assessment from

1 March up to and including the date of insolvency.

• A taxpayer who emigrates will have a year of assessment from 1 March up to the

day preceding the day that they ceased to be a resident.

• A taxpayer who earns income for the first time, however, will have a period of

assessment of 12 months irrespective of the date of employment or of commencing

to earn income.

13

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:34 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.5

• A company’s year of assessment is the financial year of the company ending during the calendar year in question.

REMEMBER

• Where the period of assessment is less than a full year, rebates will be apportioned by

the total number of days of the period as part of the full year of assessment.

Current year of assessment

The current year of assessment for natural persons starts on 1 March 2021 and ends

on 28 February 2022. For the purposes of this book and examples, if a transaction

takes place on 31 August in the current year of assessment, it means that the transaction took place on 31 August 2021.

The ‘current year of assessment’ in terms of this book will be the 2022 year of assessment, which ends on 28 February 2022. If an amount is carried over to the next year of

assessment, that is to say the 2023 year of assessment, it is carried over to 1 March

2022 (the beginning of the following year of assessment). The same principle applies

to amounts carried forward from the previous year of assessment (2021 year of assessment). These amounts are available for deduction on 1 March 2021.

1.5.2 Normal tax (section 5)

In terms of section 5(2) of the Act, the applicable rates of tax are determined annually

by Parliament. Each year, a Revenue Laws Amendment Act, which contains the

normal tax tables that must be used during that particular year of assessment, is

approved by Parliament.

The tax tables applicable to the current year of assessment are given in Appendix A

(at the back of this book) and are used to illustrate the calculation of normal tax on

taxable income.

Example 1.3

Gershane Yosh has a taxable income of R543 000 for the current year of assessment.

Vershi Yosh has a taxable income of R350 000 for the current year of assessment.

You are required to calculate Gershane and Vershi’s normal tax for the current year of

assessment.

14

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:34 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

1.5

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

Solution 1.3

R

Gershane (taxable income = R543 000)

On R467 500 (per the tax tables)

Add: 36% of R75 500

(the amount in excess of R445 100 thus R543 000 – R467 500)

Normal tax

27 180

137 919

Vershi (taxable income = R350 000)

On R337 800 (per the tax tables)

Add: 31% of R12 200

(the amount in excess of R337 800 thus R350 000 – R337 800)

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

110 739

Normal tax

70 532

3 782

74 314

Why is there a difference in the tax percentage used in the two calculations?

The example given here illustrates the calculation of normal tax on taxable income,

but can also be used to explain the two concepts often referred to in tax literature,

namely the marginal and the average rate of tax.

• Marginal rate of tax This rate of tax applies to an additional R1 of taxable income

earned. Referring to Example 1.3, the marginal rate of income tax is 36% because if

Gershane earned R1 more of taxable income, she would have to pay 36% tax on

this R1.

• Average rate of tax This is the rate of tax applying to the total taxable income.

Gershane’s average rate of tax is

R137 919

× 100, therefore the average rate is 25,4%.

R543 000

The marginal rate of tax is high but the average rate of tax is much lower. For natural

persons, the maximum marginal tax rate of 45% comes into operation on taxable

income in excess of R1 656 600.

REMEMBER

• When you evaluate the tax implications of a specific transaction, you always refer to the

marginal tax rate.

1.5.3 Normal tax rebates for natural persons (section 6)

Section 6 of the Act prescribes certain normal tax rebates to be deducted from the normal

tax payable by natural persons. Natural persons qualify for the following three rebates:

• primary rebate (all natural persons)

–

R15 714;

• secondary rebate (natural persons over 65 years of age)

–

R8 613; and

• tertiary rebate (natural persons over 75 years of age)

–

R2 871.

15

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:36 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.5

The total rebates can be summarised as follows:

Age of the taxpayer

Total rebates

Under 65 years of age

R15 714

65 years but less than 75 years of age

R24 327 (R15 714 + R8 613)

75 years and older

R27 198 (R15 714 + R8 613 + R2 871)

Normal tax rebate rules

• To qualify for the secondary rebate (over 65 rebate), the taxpayer must be 65 years

of age or older on the last day of the year of assessment (or would have been had

they lived to that day). The same applies to the tertiary rebate.

• When the taxpayer’s year of assessment is less than 12 months (for example where

the taxpayer dies or the date of insolvency is before 28/29 February), all three of

the above-mentioned rebates will be reduced proportionally.

• If the normal tax rebates exceed the normal tax, these rebates only reduce the

normal tax liability to zero and do not create a tax refund.

Calculation of normal tax liability

Step 1–6:

Calculate the total taxable income for the year, as explained earlier.

Step 7:

Calculate the normal tax by using the tax table.

Step 8:

Determine the age of the taxpayer at 28/29 February of the current year

of assessment. Determine if the taxpayer will qualify for the full rebate in

the year of assessment. If not, the rebate should be reduced pro rata.

Step 9:

The normal tax liability will be the normal tax (Step 7) for the year

minus rebates (Step 8).

Example 1.4

Victoria Dlamini was 83 years old when she died on 31 August 2021. She earned a taxable

income of R160 000 from 1 March 2021 to 31 August 2021.

You are required to calculate Victoria’s normal tax liability for the current year of assessment.

16

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:36 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.5

Solution 1.4

R

Taxable income (given)

R

160 000

Normal tax on R160 000 @ 18%

Less: Normal tax rebates: 83 years of age

• Primary rebate (natural person)

• Secondary rebate (over 65)

• Tertiary rebate (over 75)

28 800

15 714

8 613

2 871

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

27 198

Reduced pro rata (Note)

184 days / 365 days × R27 198

(13 711)

Normal tax liability

15 089

Note

Due to the fact that the taxpayer died during the year of assessment, the tax period is less

than 12 months; therefore the rebate should be reduced on a pro rata basis using days.

Do the rebates remain the same for every year?

REMEMBER

• If the tax less the rebate results in a negative amount, the answer is limited to nil.

• If a person starts to work during the year, they will still qualify for the full annual

rebate, as their tax year is for a period of 12 months although they only worked for a

couple of months.

• The rebate must be deducted from normal tax and not from taxable income.

1.5.4 Medical scheme fees tax credit (MTC) (section 6A)

Section 6A of the Act allows deduction of a medical scheme fees tax credits. The tax

credit applies to contributions made to registered medical schemes. The medical

scheme fees tax credit is calculated as follows:

• R332 in respect of benefits to the person;

• R664 in respect of benefits to the person and one dependant; or

• R664 in respect of benefits to the person and one dependant, plus R224 in respect

of benefits to each additional dependant, for each month in which those fees are

paid.

17

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:37 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.5

REMEMBER

For the purposes of the tax credit, a dependant is

• the spouse, partner, dependent children or other members of the taxpayer’s immediate

family. The taxpayer must be responsible for their care and support; or

• any other person who in terms of the rules of the medical scheme to which the taxpayer

belongs, is recognised as a dependant and eligible for benefits.

A ‘child’ is defined as the taxpayer’s child or a child of their spouses.

Children, for the purposes of this section, must have been alive during any portion of the

year of assessment and must be unmarried on the last day of the year of assessment and

must:

(a)

not be (or, had they lived, would not have been) over the age of 18; or

(b) be wholly or partially dependent for their maintenance on the taxpayer and not be

liable for the payment of normal tax in the year of assessment concerned and not be

(or, had they lived, would not have been) over the age of 21; or

(c)

be wholly or partially dependent for their maintenance on the taxpayer and not be

liable for the payment of normal tax in the year of assessment concerned, and, to the

Commissioner’s satisfaction, be a full-time student at an educational institution of a

public character, and not be (or, had they lived, would not have been) over the age of

26; or

(d) due to physical or mental infirmity, be unable to maintain themselves and be wholly

or partially dependent for their maintenance on the taxpayer and not be liable for the

payment of normal tax.

Where more than one person pays fees to a medical scheme, the medical tax credits

listed above must be apportioned between the people paying in the same proportion

as their payment is to the total payment.

18

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:37 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.5

Example 1.5

Joseph Roos is 35 years old and married to Refilwe (34 years old). They have one child,

Susan (seven years old). None of them have any disabilities. Joseph’s taxable income for

the current year of assessment is R250 000. Joseph is the main member of the medical

fund.

You are required to

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

(a)

calculate Joseph’s normal tax liability for the current year of assessment assuming

that Joseph makes the full medical aid payment in respect of himself, his wife and

child;

(b) calculate the amount that Refilwe can claim as a medical tax credit if the full medical

aid payment that Joseph is required to make is R3 000 per month and she pays

R1 000 of the payment.

Solution 1.5

(a)

Joseph’s normal tax liability

Calculate the medical scheme fees tax credits:

(R664 (Joseph + Refilwe) + R224 (Susan)) × 12 months = R10 656

Calculation of normal tax liability:

R

Taxable income

250 000

Normal tax (R38 916 + (26% × (R250 000 – R216 200)))

Less: Primary rebate

Less: Medical scheme fees tax credit ((R664 + R224) × 12 months)

47 704

(15 714)

(10 656)

Normal tax liability

21 334

(b) Refilwe’s medical scheme fees tax credit

MTC calculated as above – R10 656

Apportioned for Refilwe’s payment – R10 656 × R12 000 / R36 000

3 552

Note

In this case Joseph’s MTC would also be apportioned and he would be able to deduct a

tax credit of R7 104.

1.5.5 Additional medical expenses tax credit (AMTC) (section 6B)

There will be an additional medical expenses tax credit (additional medical tax credit)

for medical expenses. The Act provides for the following qualifying medical expenses

to be considered for an additional medical tax credit:

(1) Amounts (that have not been recovered from the medical scheme) that were paid

by the taxpayer during the year of assessment to

19

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:43 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.5

(a) a medical practitioner, dentist, optometrist, homeopath, naturopath, osteopath, herbalist, physiotherapist, chiropractor or orthopaedist for professional

services rendered or medicines supplied to the taxpayer or their spouse or

child, or a dependant of the taxpayer if the taxpayer was a member of a

scheme or fund and the dependant was, at the time the amounts were paid,

admitted as a dependant of the taxpayer in terms of the fund;

(b) a nursing home or hospital or a nurse, midwife or nursing assistant or to a

nursing agency for the services of such a nurse, midwife or nursing assistant

because of the illness or confinement of the taxpayer or their spouse or child

or a dependant as contemplated in item (a); or

(c) a pharmacist for medicines supplied on the prescription of a person mentioned in item (a) above for the taxpayer or their spouse or child.

(2) Amounts (that have not been recovered from the medical scheme) that were paid or

contributed by the taxpayer during the year of assessment for expenditure incurred

outside the Republic on services rendered or medicines supplied to the taxpayer

or their spouse or child that are substantially similar to the services and medicines for which a deduction may be made under item (a), (b) or (c) above.

(3) Expenditure (that has not been recovered from the medical scheme) necessarily

incurred and paid by the taxpayer in consequence of a disability suffered by the

taxpayer or their spouse or child or a dependant as contemplated in item 2(a).

REMEMBER

• The medical scheme and all practitioners and nurses referred to above have to be registered with their respective controlling bodies and in terms of certain Acts.

Taxpayers 65 and over

All contributions and expenses will be converted into medical tax credits. A taxpayer 65 and

over the age of 65 will be entitled to the following credits:

• the standard monthly medical scheme fees tax credit in respect of any contributions paid to a medical scheme – same as all other taxpayers (section 6A);

• a 33,3% credit for any contributions paid that exceed three times the medical tax

credit (as calculated in the first bullet above); and

• a 33,3% additional medical tax credit based on all qualifying medical expenses not

refunded by medical scheme (excluding contributions).

Example 1.6

David Hess is 66 years old. For the year of assessment commencing 1 March 2021, he

made contributions of R3 000 per month to a medical scheme on behalf of himself and his

wife. He paid R23 500 qualifying medical expenses for the year. David earned a salary of

R340 000.

You are required to calculate David’s medical tax credits for the 2022 year of assessment.

20

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:43 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

1.5

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

Solution 1.6

Medical scheme fees tax credit (R664 × 12 months)

Excess medical scheme fees credit

(R36 000 (monthly contributions) ï (3 × R7 968)) × 33,3%

Additional medical expenses tax credit (R23 500 × 33,3%)

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Total medical tax credits that will reduce his normal tax

R

(7 968)

(4 028)

(7 826)

(19 822)

Taxpayers with a disability

Where the taxpayer is not yet 65 years old and the taxpayer, spouse and/or child is a

person with a disability, they will be entitled to the following credits against normal

tax:

• the standard monthly medical tax credit in respect of any contributions paid to a

medical scheme – same as all other taxpayers;

• a 33,3% credit for any contributions paid that exceed three times the tax credit (as

calculated in the first bullet above); and

• a 33,3% additional medical tax credit based on all qualifying medical expenses not

refunded by medical scheme (excluding contributions).

Example 1.7

Lisa Sharpe is 35 years old. For the year of assessment commencing 1 March 2021, she

made contributions of R2 000 per month to a medical scheme on behalf of herself and her

two children. She paid R23 500 qualifying medical expenses for the year. Her employer

contributed R15 000 to the medical scheme during the year. Lisa earned a salary of

R275 000. Lisa’s son has a disability.

You are required to calculate Lisa’s medical tax credits for the 2022 year of assessment.

Solution 1.7

R

Medical scheme fees tax credit (R664 + R224) × 12 months

(10 656)

Excess medical scheme fees credit (R24 000 (own contributions) + R15 000

(fringe benefit employer contributions) – (3 × R10 656)) × 33,3%

(2 342)

Additional medical tax credit (R23 500 × 33,3%)

(7 826)

Total tax credits

(20 824)

Taxpayers not yet 65 years old

These taxpayers will be entitled to the following credits that will reduce normal tax:

• the standard monthly medical tax credit in respect of any contributions paid to a

medical scheme – same as all other taxpayers;

21

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:44 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.5

• an additional medical tax credit equal to 25% of the sum of:

– any contributions paid that exceed four times the tax credit (as calculated in the

first bullet above); and

– qualifying medical expenses

that exceed 7,5% of the taxpayer’s taxable income.

Example 1.8

Joe Blunt is 35 years old. For the year of assessment commencing 1 March 2021, he made

contributions of R6 000 per month to a medical scheme on behalf of himself, his wife and

a child. He paid R50 000 qualifying medical expenses for the year. His employer contributed R40 000 to the medical scheme during the year. Joe earned a salary of R500 000.

You are required to calculate Joe’s medical tax credits for the 2022 year of assessment.

Solution 1.8

Medical scheme fees tax credit (R664 + R224) × 12 months

Additional medical expenses tax credit: 25% of:

Excess contributions (R6 000 × 12 + R40 000) – (4 × R10 656)

Add: Qualifying expenses

Less: 7,5% × taxable income (R540 000) (Note)

R

(10 656)

R69 376

R50 000

(R40 500)

R78 876

Therefore: R78 876 × 25%

(19 719)

Note

Calculation of taxable income

Salary

Medical fringe benefit (employer’s contributions)

500 000

40 000

540 000

REMEMBER

For the purposes of the tax credit a dependant is

• the spouse, partner, dependent children or other members of the taxpayer’s immediate

family. The taxpayer must be responsible for their care and support; or

• any other person who in terms of the rules of the medical scheme to which the taxpayer

belongs, is recognised as a dependant and eligible for benefits.

A ‘child’ is defined as the taxpayer’s child or a child of their spouses.

continued

22

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:44 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.5

Children, for the purposes of this section,

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

must have been alive during any portion of the year of assessment and must be unmarried on the last day of the year of assessment and:

(a)

not (or, had they lived, would not have been) over the age of 18; or

(b)

wholly or partially dependent for their maintenance upon the taxpayer and not

liable for the payment of normal tax in the year of assessment concerned and not

(or, had they lived, would not have been) over the age of 21; or

(c)

wholly or partially dependent for their maintenance on the taxpayer and not liable

for the payment of normal tax in the year of assessment concerned, and, to the

Commissioner’s satisfaction, a full-time student at an educational institution of a

public character, and not (or, had they lived, would not have been) over the age of 26;

or

(d)

due to physical or mental infirmity, was unable to maintain themselves and was

wholly or partially dependent for their maintenance on the taxpayer and was not

liable for the payment of normal tax.

1.5.6 Rebate in respect of foreign taxes on income (section 6quat)

If a resident includes foreign income in their taxable income on which they also paid

tax in another country, they can qualify for a rebate for the tax they paid (section

6quat, refer to chapter 5).

1.5.7 Prepaid taxes

The final step in calculating a person’s final tax liability is to reduce normal tax liability by any prepayments of tax made during the year of assessment. Prepayments of

tax would normally consist of one or more of the following payments:

• employees’ tax deducted by the employer during the year of assessment from a

wage, salary or similar earnings (also known as Pay as You Earn (PAYE)) (chapter 11);

• provisional tax paid by the taxpayer during the year of assessment (chapter 11).

Where a taxpayer owes an amount of tax and has not paid the amount by the due

date (second date), interest is added to the normal tax liability . If a taxpayer has

overpaid an amount of tax owing, (under certain circumstances) interest is credited.

These interest rates are determined by SARS from time to time (refer to Annexure F).

If a taxpayer still owes an amount of normal tax at the end of the year, it is referred to

as a net debit. If, however, the taxpayer paid more than the tax due, they have a net

credit, which will be refunded to them.

23

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:45 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.5–1.6

Example 1.9

Mpho Zuma is 44 years old and her normal tax payable (after rebates and credits) for the

current year of assessment amounts to R25 250. Her employer deducted R20 000 employees’ tax from her monthly salary. She is also registered as a provisional taxpayer and paid

R8 500 provisional tax during the current year of assessment.

You are required to calculate how much Mpho still owes SARS or how much she will be

refunded for the current year of assessment.

Solution 1.9

R

25 250

Normal tax liability

Less: Prepaid taxes:

Employees’ tax

Provisional tax

(20 000)

(8 500)

Net credit (amount due to Mpho)

(3 250)

REMEMBER

• If the net amount due is negative (net credit), taxpayers are entitled to a refund of the

amount they overpaid during the year of assessment.

• If a refund is due, SARS will first refund the provisional tax paid and then the PAYE.

1.6 Tax returns, assessments and objections

Persons earning a monthly salary receive a salary slip (or a salary advice) at the end

of each month indicating how much they have earned, what deductions were made

and how much tax has been deducted by the employer. Shortly after the end of the

year of assessment the employer must prepare an IRP5 for each employee.

The IRP5 shows the total remuneration paid during the year, certain deductions

made by the employer, such as retirement fund and medical aid fund contributions,

and the total employees’ tax deducted during the year, as well as other information.

The employer submits the IRP5 information to SARS. SARS then includes all this

information in a taxpayer’s prepopulated tax return (ITR12) on the efiling system.

If a person earns income from sources other than employment, they prepay their tax

on such other income by means of provisional tax. The taxpayer must complete an

IRP6 form to calculate the amount of provisional tax due.

SARS has introduced a fully electronic filing system (e-filing) for the submission of

income tax returns. Where a taxpayer is required to submit an annual tax return, they

need to request the return to be issued on SARS e-filing. In the case of individuals, the

form is an ITR12 (which includes the information discussed above) and an ITR14 in

the case of companies. After the taxpayer has completed the tax return on the e-filing

system and submits it electronically to SARS, SARS uses the information to calculate

the normal tax liability for the year of assessment.

24

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:45 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

1.6–1.7

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

An ITR12 is prepopulated and the taxpayer must provide details of other income and

expenditure in order to calculate the normal tax payable. Persons who derive income

from business are also required to prepare a statement of assets and liabilities. This

section assists SARS in identifying undeclared income and possible tax evasion

practices.

After receiving the tax return, SARS processes the return and issues a tax assessment

(recorded on an ITA34) to each taxpayer. The ITA34 shows:

• the total taxable income for the year of assessment;

• the normal tax on this taxable income;

• a sub-total after the deduction of rebates (in this book referred to as normal tax

liability)

• the provisional tax paid for the year;

• employees’ tax in respect of the year;

• the net debit or credit;

• any balance of tax or interest owing from a previous year of assessment; and

• the final net debit or credit for the year of assessment.

The assessment has a date, a due date and a second date (the final date for payment

of the amount owing). The date is the date on which the assessment was processed.

The payment of any outstanding taxes may be made in cash, by cheque or electronically.

Sometimes, the assessment issued by SARS does not agree with the taxpayer’s own

calculation. In these situations, the Act allows the taxpayer to object to their assessment. The objection has to be in writing (on the prescribed form (ADR1) via e-filing),

setting out the reasons for the objection, and must be submitted electronically to SARS

within the prescribed period (usually 21 business days).

SARS will consider the taxpayer’s objection and either issue a revised assessment or

confirm the assessment issued. If the taxpayer is not satisfied with the reasons given

for the assessment or partially changed assessment, they have the right to appeal

against the assessment in a court of law.

1.7 Tax practitioners

SARS requires all natural persons who provide tax advice or complete or help to

complete tax returns to register as tax practitioners. A person must register with

SARS as well as with a recognised professional body within 21 business days from

the date they start delivering these services.

The following persons are not required to register:

• if the advice or service is provided for no consideration;

• if the services are provided in anticipation of actions against SARS;

• if the services are incidental to or a subordinate part of a person’s business;

• if the person is a full-time employee and renders service to their employer; or

• if the person is under the direct supervision of a person that is registered.

25

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:41 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.7–1.8

If a person does not register within the required period, they are guilty of an offence

and liable for a fine or imprisonment (not exceeding 24 months).

1.8 Summary

In this chapter the basic steps for calculating taxable income were discussed. This was

followed by a discussion of the steps used to calculate a taxpayer’s tax liability for the

year of assessment. You should now be able to answer the critical questions asked at

the beginning of the chapter.

In the following chapters, the details of the framework below are discussed. It is

therefore very important that you understand the content of this chapter as it forms

the basis for all the chapters that follow.

Gross income (as defined in section 1)

Less:

Exempt income (sections 10, 10A and 12T)

Less:

Add:

Add:

Less:

Less:

Income (as defined in section 1)

Deductions (section 11 – but see below; subject to section 23(m) and

assessed loss (sections 20 and 20A)

Taxable portion of allowances

(section 8 – such as travel and subsistence allowances)

(xxx)

Taxable income before taxable capital gain

Taxable capital gain (section 26A)

Taxable income before retirement fund deduction

Retirement fund deduction (section 11F)

Taxable income before donations deduction

Donations deduction (section 18A)

xxx

xxx

xxx

(xxx)

xxx

(xxx)

Taxable income (as defined in section 1)

Normal tax calculated based on the tax tables

Less:

Annual rebates (section 6)

Less:

Medical tax credits (sections 6A and 6B)

Less:

Add:

R

xxx

(xxx)

Normal tax liability for the year

PAYE and provisional tax (pre-paid taxes)

Withholding taxes

Final tax liability of natural person

xxx

xxx

xxx

xxx

(xxx)

(xxx)

xxx

(xxx)

xxx

xxx

xxx

The next section contains questions that allow you to test your knowledge on the calculation of tax payable.

26

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:41 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

1.9

Chapter 1: Introduction to taxation and calculation of net tax payable

1.9 Examination preparation

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Question 1.1

Sipho and Andele Baloi are married in community of property.

Andele (55 years of age) received the following income during the year of assessment:

• a salary of R225 000;

• interest of R170 000 on an investment account with a South African bank (not a tax free

investment).

Sipho (66 years of age) received the following income during the year of assessment:

• a salary of R400 000;

• interest of R18 000 on his savings account at a local bank.

Sipho paid retirement annuity fund contributions amounting to R60 000 (all tax deductible) during the current year of assessment. During the current year he also paid municipal

costs of R80 000 which relate to his private house.

You are required to:

Calculate Sipho and Andele’s taxable income for the current year of assessment.

Answer 1.1

Calculation of Andele’s taxable income:

Gross income

• Salary

• Interest received (Note 1)

R

225 000

94 000

319 000

Less: Exempt income

• Interest received (Note 2)

(23 800)

Income

Less: Deductions

295 200

nil

Taxable income

295 200

Calculation of Sipho’s taxable income:

Gross income

• Salary

• Interest received (Note 1)

400 000

94 000

494 000

Less: Exempt income

• Interest received (Note 2)

(34 500)

Income

Less: Deductions

• Private home cost (Note 3)

• Retirement fund contributions

459 500

Taxable income

399 500

nil

(60 000)

continued

27

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:47 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

1.9

Notes

1. As Andele and Sipho are married in community of property, the interest received must

be divided equally between both spouses. Therefore Andele and Sipho must include

R94 000 ((R170 000 + R18 000) / 2 = R94 000) interest in their gross income.

2. Each taxpayer qualifies for an interest exemption on his or her portion of the interest.

As Sipho is over 65 years of age he qualifies for an exemption of R34 500. Andele qualifies for an exemption of R23 800 on interest received.

3. A taxpayer is not allowed to claim any private costs for income tax purposes.

Additional questions for this chapter are available electronically at

www.myacademic.co.za/books

28

EBSCOhost - printed on 4/11/2022 9:47 AM via UNISA. All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Copyright 2022. LexisNexis SA.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

2

Gross

income

General

definition

–

Gross income

Exempt

income

Specific

inclusions

–

Deductions

=

Taxable

income

Tax

payable

Fringe

benefits

Page

2.1

Introduction .........................................................................................................

30

2.2

Definition of ‘gross income’ (section 1) ............................................................

31

2.3

Resident of the Republic.....................................................................................

2.3.1 Ordinarily resident ................................................................................

2.3.2 ‘Physical presence’ test..........................................................................

32

33

35

2.4

Total amount in cash or otherwise....................................................................

38

2.5

Received by or accrued to or in favour of ........................................................

40

2.6

Year or period of assessment .............................................................................

52

2.7

Receipts or accruals of a capital nature ............................................................

2.7.1 Subjective tests .......................................................................................

2.7.2 Objective factors .....................................................................................

2.7.3 Specific types of transactions ...............................................................

52

54

63

68

2.8

Special inclusions (section 1 ‘gross income’ definition) .................................

2.8.1 Annuities (paragraph (a)) .....................................................................

2.8.2 Alimony, allowances or maintenance (paragraph (b)) .....................

2.8.3 Amounts received in respect of services rendered, employment,

or holding an office (paragraphs (c), (cA), (cB), (d ), (f ) and (i))........

2.8.4 Retirement fund lump sum benefits or retirement fund

lump sum withdrawal benefits (paragraphs (e) and (eA)) ...............

74

74

76

29

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/11/2022 9:43 AM via UNISA

AN: 3149493 ; Bruwer.; Students Approach to Income Tax: Natural Persons 2022

Account: s7393698.main.ehost

76

77

A Student’s Approach to Income Tax/Natural Persons

2.1

Page

2.8.5

2.8.6

2.8.7