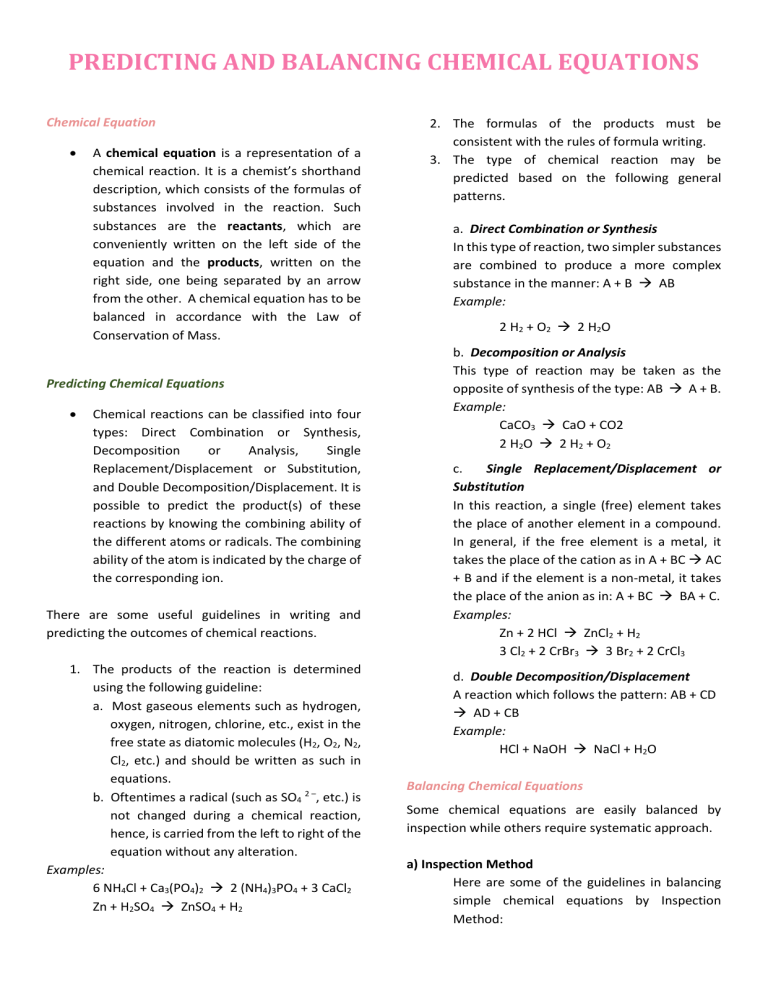

PREDICTING AND BALANCING CHEMICAL EQUATIONS Chemical Equation A chemical equation is a representation of a chemical reaction. It is a chemist’s shorthand description, which consists of the formulas of substances involved in the reaction. Such substances are the reactants, which are conveniently written on the left side of the equation and the products, written on the right side, one being separated by an arrow from the other. A chemical equation has to be balanced in accordance with the Law of Conservation of Mass. Predicting Chemical Equations Chemical reactions can be classified into four types: Direct Combination or Synthesis, Decomposition or Analysis, Single Replacement/Displacement or Substitution, and Double Decomposition/Displacement. It is possible to predict the product(s) of these reactions by knowing the combining ability of the different atoms or radicals. The combining ability of the atom is indicated by the charge of the corresponding ion. There are some useful guidelines in writing and predicting the outcomes of chemical reactions. 1. The products of the reaction is determined using the following guideline: a. Most gaseous elements such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, chlorine, etc., exist in the free state as diatomic molecules (H2, O2, N2, Cl2, etc.) and should be written as such in equations. b. Oftentimes a radical (such as SO4 2 –, etc.) is not changed during a chemical reaction, hence, is carried from the left to right of the equation without any alteration. Examples: 6 NH4Cl + Ca3(PO4)2 2 (NH4)3PO4 + 3 CaCl2 Zn + H2SO4 ZnSO4 + H2 2. The formulas of the products must be consistent with the rules of formula writing. 3. The type of chemical reaction may be predicted based on the following general patterns. a. Direct Combination or Synthesis In this type of reaction, two simpler substances are combined to produce a more complex substance in the manner: A + B AB Example: 2 H2 + O2 2 H2O b. Decomposition or Analysis This type of reaction may be taken as the opposite of synthesis of the type: AB A + B. Example: CaCO3 CaO + CO2 2 H2O 2 H2 + O2 c. Single Replacement/Displacement or Substitution In this reaction, a single (free) element takes the place of another element in a compound. In general, if the free element is a metal, it takes the place of the cation as in A + BC AC + B and if the element is a non-metal, it takes the place of the anion as in: A + BC BA + C. Examples: Zn + 2 HCl ZnCl2 + H2 3 Cl2 + 2 CrBr3 3 Br2 + 2 CrCl3 d. Double Decomposition/Displacement A reaction which follows the pattern: AB + CD AD + CB Example: HCl + NaOH NaCl + H2O Balancing Chemical Equations Some chemical equations are easily balanced by inspection while others require systematic approach. a) Inspection Method Here are some of the guidelines in balancing simple chemical equations by Inspection Method: 1. Coefficients are written before the formulas. Subscripts for atoms in the correct formulas are never changed to balance an equation because such change would mean another substance or maybe wrong formula. Begin to balance by starting with the most complicated formula. Example: H3PO4 + Ba (OH)2 Ba3(PO4)2 + H2O The most complicated formula, Ba3(PO4)2, indicates that three barium atoms and two phosphate ions are needed. Hence coefficient 3 is written before Ba (OH)2 and coefficient 2 is written before H3PO4. These two coefficients give a total of six hydrogen atoms and six hydroxyl (OH – ) on the left so the coefficient 6 is written before H2O on the right. Thus, the balanced equation is: 2 H3PO4 + 3 Ba(OH)2 Ba3(PO4)2 + 6 H2O 2. Coefficients are reduced to the smallest whole number. The equation 4 Na(s) + 2 Cl2(g) 4 NaCl(s) is balanced but the coefficients can be divided by two, so the final balanced equation is: 2 Na(s) + Cl2(g) 2 NaCl(s) 3. The final balanced equation should not contain fractional coefficients (except when writing thermochemical equations). The equation C2H6 + 3 ½ O2 2 CO2 + 3 H2O is balanced but should be written as 2 C2H6 + 7 O2 4 CO2 + 6 H2O to eliminate the fractional coefficient. 4. The balanced equations are always checked to make sure every element is represented by the same number of atoms on both sides of the equation. b) Matrix Method Source: Alternative Chemistry Teaching Strategies (Cabigon, 2013) The following steps are suggested for balancing ordinary chemical equations by Matrix Method: 1. Write the skeletal equation. The skeletal equation should be written with the correct formulas of reactants followed by an arrow and the correct formulas of the products. Remember that for most elements, the formulas correspond to their symbols except for seven elements which are represented as diatomic molecules (H2, O2, N2, F2, I2, Br2, and Cl2) and a few elements as polyatomic (P4 and S8, although they are mostly represented as P and S only). 2. Under the skeletal equation, draw a matrix table with the individual elements under the arrow column starting from the element with the highest atomic number except oxygen which should be written last. Indicate the number of atoms of each element under the compound or element column; this number is taken from the subscripts of the elements or from the product of the subscripts in case there are substances enclosed in parenthesis. See example below. 3. You may forget the given equation for now and focus on the matrix table. Inspect each row in the table to find out if the number of atoms is the same before and after the arrow. Add all the atoms on the reactant side and all the atoms on the product side for each element or row to check if they are the same. If not, multiply the lesser number by a whole number to make the number of atoms before and after the arrow equal. The number you multiplied to the lesser number should also be multiplied to all the numbers in the same column. For example, to balance the Al in the equation, multiply 1 in Al(OH)3 column by 2 to make it equal to 2 under Al2(SO4)3 column. You also multiply by 2 all the numbers in the same column as shown: 4. Go to the next atom, S. The S under H2SO4 is multiplied by 3 to make it equal to 3 for S under Al2(SO4)3. All the numbers in the column are also multiplied by 3. 5. Go to the next atom, H. the total number of H is 12 (6 under Al(OH)3 and 6 under H2SO4). Thus, multiply 2 under H2O by 6 to obtain 12. You also multiply all the numbers in the column by 6. 6. Go to the last atom, O. Because the total number for O atoms in the reactant side is 18 (6 under Al(OH)3 and 12 under H2SO4) and equals the total number of 18 in the product side (12 under Al2(SO4)3 and 6 under H2O), the number of oxygen atoms is now balanced and so the equation is also balanced. We simply use the numbers used to multiply in each column to write the balanced equation: 2 for Al(OH)3, 3 for H2SO4, and 6 for H2O. The balanced equation is thus, 2 Al(OH)3 + 3 H2SO4 Al2(SO4)3 + 6 H2O oxidation number of zero. Example: Na0, O20 2. Since compounds are electrically neutral, the sum of the oxidation numbers of all the atoms in a compound is zero. Example: H31+P5+O42– (3)(1+) + (1)(5+) + (4)(2-) = 0 3. The oxidation number of a monatomic ion is the same as the charge on the ion (electrovalence number). In the case of polyatomic ions, the sum of the oxidation numbers of all the atoms is equal to the net charge on the ion. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Balancing Oxidation-Reduction Reactions Oxidation-reduction reaction involves a change in oxidation numbers of the atoms. Oxidation numbers are charges assigned to the atoms of a compound according to arbitrary rules which take into account bond polarity. Rules on Assigning Oxidation Numbers 1. Any uncombined atom or any atom in a molecule of an element is assigned an 1. The oxidation number of F, the most electronegative element, is 1in all compounds containing F. In most oxygen-containing compounds, the oxidation number of oxygen is 2-. In peroxides, oxygen has an oxidation number of 1-. In OF2, oxygen has an oxidation number of 2+. The oxidation number of hydrogen is 1+ in all its compounds except the metallic hydride (CaH2 and NaH) in which hydrogen is in the 1oxidation state. Combined alkali metals have 1+ oxidation state. Combined alkaline-earth metals have 2+ oxidation states. Combined halogens have 1- oxidation state. Steps in Balancing Oxidation-Reduction Reactions 1. Write the skeletal equation. 2. Determine the oxidation number of each element in the equation. 3. Based on the oxidation numbers, identify the element that undergoes oxidation (the oxidation number increases from reactant to product side) and the element that undergoes reduction (the oxidation number decreases from reactant to product side). 4. Set up the oxidation and reduction half– reactions. Balance the elements by writing appropriate coefficients. 5. Balance the charges on both sides of the equation by adding enough electrons to the more positive side. 6. Balance the number of electrons lost (oxidation half-reaction) and gained (reduction half-reaction) by the multiplying appropriate factor by the half-reactions. 7. Add the two half-reactions to obtain the partially balanced equation. 8. Use the coefficients obtained in the partially balanced equation into the original equation and balance the rest of the equation using the Matrix Method.