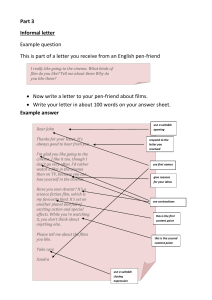

TOPIC 61. THE IMPACT OF THE CINEMA IN THE SPREAD OF LITERARY PRODUCTION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE. The topic I have selected is number 61, entitled The impact of the cinema in the spread of literary production in English language. It comprises the notions of the development of the cinema since the 1920s, films and the English language, cinema and literature, the teaching inference, a conclusion and the bibliography. The unit chosen becomes absolutely indispensable within the curriculum of EFL. In compliance with the Organic Law LOMLOE 3/2020, December 29th, it is important to promote the need to understand and express oneself fluently and correctly in this language. Likewise, it fosters communicative, socio-cultural and multilingual competences, belonging in turn to the cultural block of contents. Then, it is undeniable that for an ESL teacher, the richness of contents that this subject matter involves is priceless, especially if we give account for the multiple communicative strategies students need to master before becoming efficient in English. In order to provide a better understanding of this unit, it is crucial to give some details about the background. According to Parkinson (1995), “The majority of film experts now agree that cinema began with the Lumière’s show on 28 December 1895.” They brought up a new technological invention which was the recording of images that were later projected in a continuous and connected way, being also able to reproduce the movement of actual people and things. The first manifestations were simple documentaries of daily life events, towards which viewers were really amazed due to the realism and vivid way in which they were created, even finding something magic in it. We can clearly assure that the origins of the cinema were popular and humble from the very beginning. It started as an entertainment in the fairs, closer to the circus than to artist consideration. The storytelling lying behind the filmic productions got clearly inspired in the theatre plays’ forms and expressive resources, with fixed cameras and simple settings. But before the 1920s, cinema had approached narrative fiction and the novel. The young art turned to the novel because it was soon felt that it was the most similar artistic manifestation, both in its aims and resources and also in the way of telling stories. Regarding the cinema in the 1920s, we can affirm that it reached a higher level of perception as a means of telling stories in the twenties. Following Shiach (1993), “By the twenties, movies were very big business indeed.” It is also the time when many celebrities such as Charles Chaplin or Buster Keaton, and their corresponding works, became well accounted all over the world. There is this clear spreading and consolidation of this cinema, even if it is silent, as a popular show. One of the most important reasons why it had such a great penetration was the fact that it was completely affordable and unexpensive. Its stars became immensely popular and respected, and it was acclaimed by millions of people. Although the cinema was born in France, the USA (Los Angeles) soon became the setting of the massive studios of the growing film industry and, of course, English became the language that best represented it. Moving forward to the following section, we have to make reference to the introduction of the cinema in the Golden Age (1930-1960). One of the major improvements was the insertion of sound of sound in the filmic productions. In the words of Parkinson (1995), “Sound transformed cinema. Film industries sprang up around the world, as countries began to make pictures in their own languages. From here have come not only many of the most popular films of all time, but also much of the technology that makes movies going so magical.” Furthermore, speech provided new resources and possibilities of expression, creating a double semiotic system composed of images plus words. We can clearly state that these productions have created their own code or language, which are different from those of literature. The period of time between 1930 and 1960 is considered the Golden Age of Hollywood. A great number of masterpieces were produced then; in addition, cinematographic language achieved a high level and development, adapting to a great variety of genres and topics, expressing not only actions and events but also huma nature, universal anxieties, feelings and fears of modern life. Therefore, it is more like a clear reflection of what we read, for example, in novels. There were the years when the best westerns were made by directors like John Ford’s The Stagecoach (1939) and Howard Hawks’ Rio Lobo (1970). It was also the time of black cinema, when Hammett’s and Chandler’s scripts were transformed into immortal films by John Houston, such as The Maltese Falcon (1941) or The Asphalt Jungle (1950), and comedies like Billy Wilder’s Some like it hot (1959). Having covered the previous notions, it is time now to move to the 60s onwards. We can claim that changes are relatively smaller compared to earlier periods. There have been some new technological innovations like special effects and computer designs. In spite of the repetitive and commercial nature of most of the latest cinema, it is worthwhile highlighting the names of figures like F. Ford Coppola and The Godfather Trilogy (1972, 1974 and 1990), Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979) and Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Schindler’s List (1993). There is a point on which we have to reflect: the relevance of the cinema in the whole twentieth century. Cinema gained another means of diffusion, enlarging its market and influence, thanks to the appearance and spread of television. Hollywood’s big productions like those of Walt Disney or Steven Spielberg, with their huge marketing campaigns, were able to create fashions and influence the behaviour and moral values of people all over the world. It is the moment when stardoms became a clear reality with movie stars like Sharon Stone or Tom Hanks, in the same way that Ingrid Bergman or Chaplin were in the past. It has taken a long time for the cinema to be given the rank of art, but now it is not only that but also the most popular and influential one, present in everyday life, accessible and capable of creating passions, fashions and diffusing the Anglo-Saxon culture, history and way of life. Having covered the aforementioned notions, I will proceed to deal with the connection between films and the English language. As said above, the USA became the centre of the motion picture industry, dominating the screen. Because of this, they monopolise the market, turning it into a powerful aid for spreading the English culture and its language. We are at a point in which a clear division between silent and sound films is appreciated. At the time of the silent film, story developments not immediately apparent from gestures were made explicit through title cards inserted in the film. However, after sound films were introduced, three methods were used for surmounting language barriers: Multiple casts: they were the least used since they were too expensive. Subtitling: it involves the printing of translations at the bottom of the screen while actors are heard in their original speech. Dubbing: this was the device employed to overcome the language barrier due to the fact that it allows the films to be shown in many languages. It employs trained voice specialists who synchronise translated dialogues to lip movements. It is important to mention that in many countries, the English language is almost completely deleted from films. Nevertheless, original English version films are extremely good for educative purposes in learning the language, giving practice in understanding the spoken language and taking the students outside the range of classroom experience. The aforementioned theoretical framework will lead us to further describe the relationship between two arts: cinema and literature, which is highly complex. Like other arts, cinematography has developed a rich language. Confronted by the massaudience films, we are inclined to forget that watching films is as sophisticated as reading. A film is not simply a direct representation of reality because it involves subliminal processes, in particular, the ability to see visual shapes as symbols, and the immediateness. Thus, viewers are educated, voluntarily or not, in the discipline of ‘reading’ films. They are two different media of artistic expression; therefore, they use different codes (image + word language of films), and the actual simple and plain word. This fact affects the representation of detailed situations, subjective states of mind or the communication of doses of information. It is important to introduce two crucial concepts: a shot is an uninterrupted exposure of numerous frames of film, and montage is the process by which various shots are edited together to create meaning. Some directors understand them as the equivalent of the dichotomy between word and sentence. The cinema has problems at generalizing. It cannot say “a woman was in the house”: it has to show a specific woman being in the house. This degree of particularization can be a disconcerting handicap because it has to allow the audience to draw the appropriate generalization. Economic considerations are also important because there is more financial pressure on films to be popular and to find a large audience. In adapting a novel for the cinema, problems of time and tense usually arise since the cinema essentially operates in the present tense. Furthermore, these concepts make reference to the continuous changes of the time of narration of the story, either backwards (flashback) or forwards. The point of view from which the story is told can be another problem, particularly when the story is told in the first person. The only cinematic device which seems to come closer to this is the subjective camera, taking this the place of the narrator or leading character. Characters are depicted quite differently in novels as compared to their film counterparts. Film makers very unusually comment on them in a straightforward way because it is through dialogue, appearance and the development of their actions the way in which we have to depict a character in the filmic version. It is undeniable that there is a great importance of literature as a starting point for scripts because they are always preferred to adaptations, and literature exerted an enormous influence on the evolution of cinema. There was always a high tendency from the part of Hollywood to buy the rights of literary works massively. But the dependence of the cinema on literature is not a recent phenomenon because it dates back almost to the origins of cinematography and weighs heavily on its whole history. It was D. W. Griffith who re-oriented the cinema towards literature with the first American trans-codification: Enoch Arden (1864), by Tennyson. Those were the foundations. Let us briefly revise the sort of literary material that has been put to work in the film factory afterwards. 1. During the Golden Age of the cinema (1930-1960), directors heavily dropped on 19th century novels and authors such as Dickens or the Brontë sisters. A large number of adaptations of classics took place in this period, in which Hollywood showed an extraordinary vitality. David O. Selznick was an important independent producer who worked in this field. 2. Later on, this situation was altered because the audience of the time either not read anything or they did read, but not 19th century stories. Some instances of international successful films which were made from great best-sellers are The Godfather Trilogy (1972, 1974 and 1990) by Coppola, or The Silence of the Lambs (1991), by Stephen King. 3. Apart from this, a new phenomenon on the field of adaptation emerged: the miniseries. They are produced for the TV market and, generally, recycling literary material, process considered economically profitable. For this reason, we can clearly state that literature somehow benefited to the miniseries. These were unbeatable as a product of mass assumption since there is a great number of viewers hooked to them. 4. On the other hand, there was alternative literary material with authors such as Joyce, Conrad or Woolf, but this posed a problem because both form and content were difficult to transpose into the filmic language. Therefore, they could not be so market-targeted because they relied on intellectuals and critics. If the importance of literature as a source for film production had to be quantified, we could say that the proportion of American movies based on novels ranges between 30 and 50 per cent. Actually, more than three quarters of the best-film Oscars have been given to adaptations of literary works. The film industry produces hundreds of films every year, all of which are based on a script. Generally speaking, good films are based on literature. Still, there are independent directors who are capable of creating the entire product without the aid of literature. Some of the incessant and non-stop interest in literature of the filming industry are: The supply of new ideas and the number of works available are endless. The narration and the genre are connected because they have a similar articulation. Financial security: if the book was a best-seller, probably the film would be so. Profitable formula: producers buy existing material, that is, the movie rights of a book. Those who were eager readers became potential viewers, so there was a low risk that the investment actually failed. The target was clearly growing in the middle class and cinema-goers because of this dichotomy. To the film industry, a cultural-economic association with a reputable and firmly established art can be a most practical means of finding social legitimacy. The above formulations justify the following section, in which we move from literary discourse to film language because here, creating a word to word-image requires necessary alteration since it is very complex to keep the original. According to the nature of these changes and the depth of cleavage between book and film version, we can group adaptations into three basic types: transposition, reinterpretation and free adaptation. 1. Transposition: this technique consists of the text being transferred from written language to the filmic version. It is an operation carried out as if it had to be the most faithful mode of illustration, a mechanical copy, and there is barely any intrusion. One example is Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), which clearly fulfils public’s expectations. 2. Re-interpretation: this strategy consists in preserving the original text but, at the same time, doing a substantial re-interpretation. Here, they try to connect with contemporary world, the audience of the time. Moreover, some cinematic techniques are also applied in the process. In fact, the best film versions of literary works belong to this group. Some interesting examples are Dracula, by Bram Stoker (1897), Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens (1860) or Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe (1719). 3. Free adaptations: in this type of adaptation, literary text and film version are linked by analogy. The literary source only functions as raw material, as the inspirational force in the beginning of the creative process. The final product comes out of cinematography proper, and it might contain situations or characters. Thus, we can say that the result is a totally different work of art such as Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), analogy of The Waste Land (1922), by T. S. Eliot, or Conrad’s Heart of Darkness 1899), whose free adaptation is Apocalypse Now (1979), by Coppola. Up to this point, it is important to comment on the disdainful attitude of writers towards cinema because of the technological elements and the showiness of the industry. Once cinema matured and became a more powerful means of expression, many writers turned to Hollywood and then ideas were re-shaped and they even still provoked mistrust towards cinema. In spite of these conflicts, the cinema has been part of the education of modern writers, exerting an influence, either conscious or unconscious, on the way they tell their stories, structure the novels or reveal their characters. The writers of the “Lost Generation” and the realist writers of the 50s were said to have a cinematographic vision of life. In the fifties and sixties, there is also a clear parallelism between the topics and techniques of novel and cinema. In Britain, the “Angry Young Men” were clearly associated with the Free Cinema. Some of the specific influences of cinema on literature can be the fragmented structure of language and plots in modern novel, such as Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941); the sudden beginning of modern novels going straight to action; and the ‘travelling’ of the camera, linked with the progressive description in the novels. In general terms, the role of cinema in the diffusion of English and American literature is endless. When a film is made out of a book, the film usually becomes better known and popular than the original version. Some instances are Gulliver (2010), Tom Sawyer (2011) or Moby Dick (2021). Also, cartoons played an important role because of the youngest audiences’ interest, and their transformation in eager consumers of this type of cinema. Making a brief revision of English literature, we find that works have been adapted for the cinema ranging from the literature of the Middle Ages to contemporary works, for instance, The Adventures of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table (2017) or The Canterbury Tales (1972), among others. Literature, and therefore, literary language, is one of the most salient aspects of educational activity, and in this unit, we have lined its relevance to cinema. Yet, handling literary productions in the past makes relevant the analysis of literature in the 20th and 21th century, especially when we find literary adaptations to the cinema. As teachers, we should ask ourselves: What do students know about the relationship of cinema and literature through history? The importance of bringing a change in classroom teaching and learning focuses on introducing several aspects of this art since, thanks to it, we can inspire learners to broaden their horizons and to investigate about the English and American written masterpieces. This means that literary productions are an analytic tool when related to the cinema, and that teachers need to identify the potential contributions and limitations of them before we can make good use of them in the academic field. It is widely believed that films are a good classroom material since they are motivating and can help students to approach the cinema and literature of other countries. In addition, it can be used to develop our students’ listening, speaking and comprehension skills and to introduce them to the language as it is actually used since we can suggest activities such as inventing another ending for the book or film, analysing the different techniques or even establishing the main differences between the book and the film version. It is useful to mention that the webpage of Burlington gives access to graded books which can be perfectly appropriate in the academic field. In this particular case, we should focus on All about the Cinema, available for 1st Bachelorette students. Finally, new technologies and digital platforms may provide a new direction to language teaching as they set more appropriate contexts for students to experience the target language. The bibliography I have used for the development of this topic is the following: Abbot, G. (1981). The Teaching of English as an International Language. A Practical Guide. Collins. Blaim, A. (2015). Mediated Utopias: From Literature to Cinema. Peter Lang. Krishan, R. (2014). Literature and Cinema. LAP Lambert. Organic Law 3/2020, December 29th, which amends Organic Law 2/2006, of May 3, 2006, on Education. Official State Gazette, 340, December 30, 2020, 122868-122953. Parkinson, D. (1995). The Young Oxford Book of Cinema. Oxford University Press. Shiach, D. (1993). The Movie Book: An Illustrated History of the Cinema. Smithmark Pub. Shklovsky, V. (2008). Literature and Cinematography. Dalkey Archive Press.