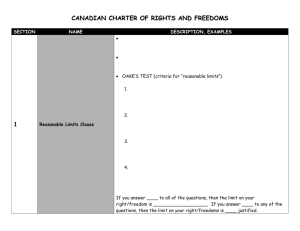

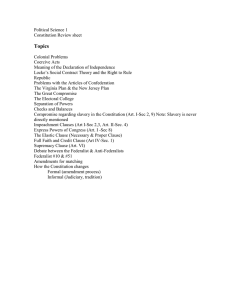

Hello, welcome to the Royal Commission on Constitutional Renewal’s report. The purpose of this commission is to examine section 33 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of the Canadian Constitution and analyze if it should be removed or not. The commission will present several facts about Section 33, detail the process for making amendments to the Constitution, and then make its recommendation. First, it is important to understand exactly what Section 33 is, and its significance to Canada. Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is also known as the Notwithstanding Clause. This clause gives Parliament and provincial legislatures the right to override certain portions of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, including Section 2, and Sections 7 to 15. These sections cover fundamental freedoms, legal rights and equality rights. When Parliament or a provincial legislature invokes the Notwithstanding Clause, it is valid for five years if it is not re-enacted. If the invocation names all sections of the Charter (2, 7-15), it does not have to provide justification for doing so. However, if Parliament or the provincial legislature only intends to override part of the provision or section, it must be stated in detail. It is also necessary to explore if Section 33 has ever been used in the past and if so, the reasons for doing so and how it was received. Section 33 has been invoked on occasion by provincial governments. Section 33 has been invoked twenty-six times since the creation of the Canadian Constitution in 1982. The first time Section 33 was evoked was in 1982, with the passing of an omnibus enticement that repealed all pre-Charter legislation and re-enacted it with the addition of a standard clause that declared the legislation to operate notwithstanding sections 2 and sections 7 to 15 of the Charter. Since then, most invocations of Section 33 have been done by Quebec, although most provinces have used it at some point. The use of the Notwithstanding Clause is often controversial, such as when Alberta invoked Section 33 in response to the federal government passing Bill C-23. Bill C-23 guaranteed samesex couples the same benefits as heterosexual couples after a year of cohabitation. When the bill was passed, Alberta responded with the passing of Bill 202, which threatened to invoke the Notwithstanding Clause should Canada ever redefine marriage to anything other than a man and woman. The issue went to the Supreme Court of Canada, with the Federal Government arguing that Alberta’s actions constituted a misuse of the Notwithstanding Clause. the Supreme Court agreed, declaring Bill 202 and its threatened use of the notwithstanding clause ultra vires. With these examples of the Notwithstanding Clause displayed, how can it be removed from the Constitution? The procedure to modify this part of the Constitution is known as the General Procedure, which is outlined as part of Part V of the Canadian Constitution. General Procedure requires that a Constitutional Amendment requires a majority of the House of Commons, a majority of the Senate, and the legislatures of a minimum of seven provinces that represent a minimum of 50% of Canada’s population to approve an amendment for it to pass. The last part of this is known as the “7/50 rule”. Because amending the Canadian Constitution requires so many separate bodies to agree to it, removing the Notwithstanding Clause from the Constitution is practically impossible in the modern political climate. Now, what is the recommendation of this Commission? It is as follows: The Commission believes that for Canadian citizens the possibility of their rights being taken away unfairly is too great a risk to allow the Notwithstanding Clause to remain a possibility. The point of the Notwithstanding Clause is that it should only be used in exceptionally rare circumstances, however as history has shown, with the Alberta case and the recent use by Doug Ford, who used it against striking teachers, there is nothing preventing elected officials from abusing this power. Government overreach is sometimes a problem; However, the Commission does not think that the solution should be a way of potentially violating constitutionally protected freedoms. Instead, a mechanism like the Supreme Court that makes sure the Government is not violating the Constitution could work. This way, provinces could appeal any law they like, and allow the court to decide. However, this Commission understands that amending the Canadian Constitution is a near-impossible thing under the current political climate, and this option may not be viable.