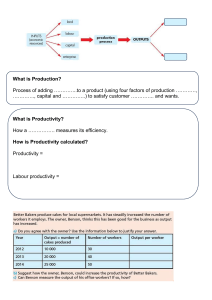

Chapter 34 Types of cost, revenue and profit, short-run and longrun production LEARNING INTENTIONS In this chapter you will learn how to: • explain the short-run production function, including: fixed and variable factors of production; total product, average product and marginal product; the law of diminishing returns (law of variable proportions) • calculate total product, average product and marginal product • explain the short-run cost function, including: fixed costs (FC) and variable costs (VC); total, average and marginal costs (TC, AC, MC); the shape of short-run average cost and marginal cost curves • calculate fixed costs and variable costs, and total, average and marginal costs • explain the long-run production function, including no fixed factors of production and returns to scale • explain the long-run cost function, including the shape of the long-run average cost curve and the minimum efficient scale • analyse the relationship between economies of scale and decreasing average costs • explain internal economies of scale and external economies of scale • explain internal diseconomies of scale and external diseconomies of scale • define the meaning of total, average and marginal revenue • calculate total, average and marginal revenue • define the meaning of normal, subnormal and supernormal profit • calculate supernormal and subnormal profit. ECONOMICS IN CONTEXT Does bigger mean better? Economies of scale in container shipping Container ships have tripled in size since container vessels were first introduced on deep-sea routes between Europe, the USA and Asia in the 1950s. The container ship the OOCL Hong Kong has a carrying capacity of over 21 000 TEU’s (twenty-foot equivalent units; one standard 45-foot container is 2 TEU). The OOCL Hong Kong is 400m long and weighs over 190 000 metric tons deadweight. Even bigger ships are under construction. OOCL and rivals such as Maersk and CMA CGM are committed to building these huge ships for one main reason – economies of scale. Figure 34.1: The OOCL Hong Kong was the world’s largest container ship at the time of its launch in 2019 Economies of scale mean lower shipping costs per container. This generates benefits further down the supply chain. It means, for example, that global manufacturers find it most economical to locate production in countries with low labour costs. This means that the lower costs of production offset the costs of transportation. Economies of scale have had a major impact on the supply chain. To give an idea of the impact, it is estimated that the cost of shipping one item of clothing from Asia to Europe in a container can be as little as $0.25. It is often forgotten that shipping is a major polluter of the air as well as the sea. For example, one container ship may emit as much pollution as 50 million cars. The emissions consist of carbon dioxide and poisonous oxides. The ships also pollute the sea with waste and oil spillage. Shipping companies argue that bigger container ships mean fewer container ships and that the latest vessels are cleaner and more efficient than those they are replacing. There is external pressure on shipping companies far beyond the benefits of economies of scale. These include threats to globalisation due to increased trade protection and the urgent need to combat climate change. Discuss in a pair or a group: • What can economists contribute to the debate on economies of scale? • Make a list of the possibilities and think about where you might be able to obtain information. 34.1 Introduction to production The demand for the four factors of production (land, labour, capital, enterprise) comes from producers who wish to use them to make various goods or products. The producer is normally a firm whose demand for factors of production is derived from the needs of operating factories. Let us look at a clothing manufacturer as an example. As a consequence of globalisation, many items of clothing are now produced in Southeast Asia, North Africa and Central Europe. This includes clothing and footwear for the mass retail market as well as designer brands such as Nike, Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren. These brands are no longer produced on any large scale in the home country of their designer. Clothing producers need factors of production in order to make goods for sale in markets that are mainly in high-income countries. Their task is to combine factors of production in an effective way to be efficient, competitive and profitable in the world market. The most important decision they have to make concerns the relative mixture of labour and capital. Therefore the task for the firm is to find the least cost or most efficient combination of labour and capital for the production of a given quantity of output. Clothing is a typical example of a business where labour and capital are in direct competition with each other. If labour costs are relatively cheap, as in lower middle-income countries, then the production process is likely to take place using much more labour than capital. In most high-income economies, the reverse is true. High-tech machines can be used to replace labour, largely because it is more cost effective to do so. So, in this case, the same amount of output is produced using more capital and far less labour than if it were taking place in a lower middle-income country. Figure 34.2: A clothing manufacturer in Bangladesh Firms therefore have to choose between alternative production methods. In the example of the clothing manufacturer, Figure 34.3 shows three different methods of production, each of which combines different levels of labour and capital to make items of clothing. Line A shows a method whereby labour and capital are used in equal proportions; line B shows a production method that uses twice as much capital as labour; line C shows the output resulting from twice as much labour as capital being used. On these lines, points x, y and z show the respective amounts of labour and capital that are needed to produce 100 units of clothing. Joining these points gives an isoquant, a curve that joins points that give a particular level of output. The isoquant can be extended for other combinations of labour and capital not shown on Figure 34.3. Figure 34.3: Alternative methods of production 34.2 Short-run production function In terms of factors of production, labour is the usual variable factor of production in the short run; all others are fixed. Table 34.1 shows how the quantity of clothing produced depends on the number of workers employed. For example, if there are no workers in the factory, there is no output or no total product; with one worker, total product is 100 units. When there are two workers, the total product is 180 units and so on. Number of workers 0 Total product Marginal product 0 Average product 0 100 1 100 100 80 2 180 90 60 3 240 80 40 4 280 70 15 5 306 51 11 6 306 51 Table 34.1: Short-run production data Figure 34.4 is a graph of the first two columns of data in Table 34.1. The graph shows the relationship between the quantity of factor inputs (labour/workers) and the total product or output of clothing. This graph is called the production function. The third column of Table 34.1 shows the marginal product, the increase in total product that occurs from an additional unit of input (labour, in this case). The data in the third column show that, when the number of workers goes from one to two, output increases by 80 units; when it goes from two to three workers, the marginal product is 60 units. As the number of workers increases, the marginal product declines. This concept is known as a diminishing return and is often referred to as the law of diminishing returns. The law of diminishing returns is clearly evidenced in many organisations. Adding more workers can be a short-term way of increasing output, but there comes a point where the marginal product falls and it might even become negative. Figure 34.4: A production function The final column of Table 34.1 shows another important measure average product. Average product is calculated by dividing the total product by the number of workers employed. It is a simple measure of labour productivity, that is, how much output is produced by each worker. TIP Learners often confuse product and productivity. This is a common error. You should remember that product is about output; productivity is about output per worker. KEY CONCEPT LINK The margin and decision-making: The law of diminishing returns is a relevant illustration of firms making choices at the margin in the short run. ACTIVITY 34.1 1 Using the data from Table 34.1, draw a graph to show: a the marginal product of labour b the average product of labour. Compare your graph with another learner’s. Discuss any differences. Now working in pairs: 2 What do you notice about the shapes of the two curves and what do the shapes indicate? 3 Explain how a knowledge of marginal and average product may be useful for a clothing firm planning how much to produce. 34.3 Short-run cost function The term 'firm' was defined in Section 1.1 and referred to in earlier chapters. More specifically, a firm has particular objectives such as profit maximisation, the avoidance of risk-taking and achieving longterm growth. At its simplest level, the firm may be a sole trader with a small factory, a food stall or a local convenience shop. A firm is also used to describe national or multinational companies with many factories and offices, such as Apple. In economic theory, all firms are headed by an entrepreneur. A firm and its entrepreneur must consider all the costs of the factors of production involved in the final output. These are the private costs directly incurred by the owners. Production may create external costs for others but these are not taken into account by the firm (see Section 33.2). The firm is simply the economic organisation that transforms factor inputs such as raw materials with capital equipment, labour and enterprise to produce goods and services for the market. Fixed costs and variable costs There are two types of short-run costs: • Fixed costs (FC) are the costs that are independent of output. Total fixed costs when drawn on a diagram take the form of a horizontal straight line as shown in Figure 34.5. At zero output, any costs that a firm has must be fixed. Some firms, where capacity is fixed or where the product is perishable as in the case of a hotel, operate in markets where fixed costs represents a large proportion of the total costs. It would be advisable to produce a large output in order to reduce unit costs or to sell all available capacity to make the firm more likely to cover total costs. • Variable costs (VC) include all the costs that are directly related to the level of output, the usual ones being labour and raw material or component costs. In other words, variable costs are incurred directly in the production process. Figure 34.5: Total cost curves Total, average and marginal costs There are five types of short-run costs: • total cost (TC) • average fixed cost (AFC) • average variable cost (AVC) • average total cost (ATC) • marginal cost (MC). Total cost (TC) = total fixed cost (TFC) + total variable cost (TVC) total fixed cost Average fixed cost (AFC) = output total variable cost Average variable cost (AVC) = output total cost Average total cost (ATC) = output change in total cost Marginal cost (MC) = change in output Marginal cost is the addition to the total cost when making one extra unit of output. These costs are shown in Figure 34.6. Figure 34.6: Average and marginal cost curves The most important cost curve for the firm is the average total cost (ATC), which shows the cost per unit of output. For most firms, the decision to increase output will raise total cost; marginal cost will be positive as extra inputs are used. Firms will only be keen to increase output when the expected sales revenue outweighs the extra cost of production. Rising marginal cost is also an indicator of the law of diminishing returns (see Section 34.2). As more of the variable factors are added to the fixed ones, the contribution of each extra worker to the total output will begin to fall. The diminishing marginal returns cause the marginal and average variable cost to rise, as shown in Figure 34.6. The shape of the short-run average cost and marginal cost curves The shape of the short-run ATC is the result of the interaction between the average fixed cost and the average variable cost: AFC + AVC = ATC. As the firm’s output rises, the average fixed cost will fall because the total fixed cost is being spread over increased output. At the same time, average variable cost will be rising because of diminishing returns to the variable factor. Eventually, this will outweigh the effect of falling AFC, causing ATC to rise. The result is the classic ‘U’ shape to the ATC curve because of the law of diminishing returns (shown in Figure 34.7). On the diagram, the MC crosses AVC and ATC at their lowest points (see Figure 34.6). It means that the most efficient output for the firm is where the average total or unit cost is lowest. This is known as the optimum output. Optimum output is where the firm is productively efficient in the short run. The most efficient output is not necessarily the most profitable, since profit maximisation may only be possible in the long run. For a firm wishing to maximise its profits, its chosen output will depend on the relationship between its revenue and its costs. Figure 34.7: Short-run ATC and MC cost curves ACTIVITY 34.2 Figure 34.8 shows the cost structure of a firm. Figure 34.8: Cost structure of a firm 1 For each cost item, say whether it is likely to be fixed or variable in the short run. 2 Use this information to say what type of industry this cost structure might represent. Justify your answer. TIP Decision making by firms is very dependent upon marginal cost in relation to the revenue that is received from producing one more unit of output. Maximum output is where marginal cost equals marginal revenue. A common error is to refer to total costs and total revenue, not marginal costs and marginal revenue. 34.4 Long-run production function The short run is a period of time in economics when at least one of the factors of production is fixed. The factor that tends to be easiest to change is labour, as explained above. The factor that takes longest to change is capital. Learners often ask the question, ‘How long is the short run?’ This is not an easy question to answer, as it tends to differ for different industries. In the clothing industry, it is likely to be no more than a few weeks, the time that is taken to install new machines and to get these up and running to produce clothing. In other industries, it will be much longer. A country building a new hydroelectric power station will take much longer to plan, install and make the power station operational. Ten years may well be a realistic estimate in this case. This time is still referred to as the short run since capital is fixed over this time. So, the short run is not defined in terms of a specific period of time; it refers to the time when not all factors of production are variable. All factors of production are variable in the long run. This gives the firm much greater scope to vary the respective mix of its factor inputs so that it is producing at the most efficient level. For example, if capital becomes relatively cheaper than labour or if a new production process is invented and this is likely to increase productivity, firms can then reorganise the way in which they produce. Firms must know the cost of the factors of production they use and consider this in relation to the additional product from using one more unit of a factor of production. In the case of labour, it is easy to know the costs; it is more difficult to estimate costs for other factors of production. The best combination of factors can be arrived at as their price varies. Firms should aim to be in a position where: marginal product factor A marginal product factor B = price of factor A price of factor B marginal product factor C = price of factor C and so on for all factors of production they use. For firms to be able to do this, all factors of production must be variable. It is possible to derive the long-run production function for a firm by constructing an isoquant map using the principles of a production function shown in Figure 34.3. The map shows the different combinations of labour and capital that can be used to produce various levels of output. The isoquant map is shown in Figure 34.9a. It consists of a collection of isoquants for output levels of 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 units of production. From this, it is possible to read off the respective combinations of labour and capital that could produce these output levels. TIP Remember that Figure 34.9a is looking at output from a physical standpoint, not a cost standpoint. A common error is to regard isoquants as cost curves. Returns to scale Figure 34.9a also shows that as production increases from 100 to 200, relatively less capital and labour is required per unit of output. This is referred to as increasing returns to scale. As production expands further, increasing amounts of capital and labour are needed to produce 100 more units of output and so move up to the next isoquant. This is indicated by the increasing width of the gap between the isoquants indicating decreasing returns to scale. Figure 34.9: Long-run production function: a Isoquant map b Isoquants and isocosts In the long run, labour and capital can be varied; the actual mix will depend upon their prices. Figure 34.9b shows lines of constant relative costs for the factors of production, known as isocosts. Each of the isocosts shown has an identical slope. In deciding how to produce, the firm will be looking for the most economically efficient or least-cost process. This is obtained by bringing together the isoquants and isocosts, so linking the physical and economic sides of the production process. The point where the isocost is tangential to an isoquant represents the best combination of factors for the firm to employ. The expansion path or long-run production function of the firm can be shown by joining together all of the various tangential points and is therefore useful from a longer-term planning perspective. It is important to recognise that the above analysis is what might happen in theory. In practice: • It is often very difficult for firms to determine their isoquants – they do not have the data or the staff know-how to be able to do this. • It is also assumed that in the long run it is possible to switch factors of production. This may not always be as easy as the theory might indicate. • Some employers may be reluctant to switch labour and capital – they may feel that they have a social obligation to their workforce and will therefore not alter their production plans with a change in relative factor prices. ACTIVITY 34.3 Table 34.2 shows the short-run and long-run factor input for a firm that has just two factors of production: capital and labour. Short run Capital Labour Long run Output Capital Labour 2 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 2 4 4 4 2 5 5 5 2 6 6 6 Table 34.2: Short- and long-run factor inputs 1 Insert your own output data in the table to show: a diminishing marginal returns b increasing returns to scale c decreasing returns to scale. Output 34.5 Long-run cost function In the long run, the firm can alter all of its inputs, using greater quantities of any of the factors of production. It is now operating on what is known as a larger scale. All of the factors of production are variable in the long run. In the very long run, technological change can alter the way the entire production process is organised, including the nature of the products themselves. In a society with rapid technological progress, this will shrink the time period between the short run and the long run. In turn, this will shift the firm’s product curves upwards and its cost curves downwards since firms are more efficient as a consequence of new technologies. There are examples in consumer electronics where whole processes and products have become obsolete in a matter of months, let alone years. For example, mobile phones evolved into smartphones and are likely to continue to change in the future. An even bigger challenge is to reduce the use of fossil fuels in transport systems. The switch to electric cars, buses and other vehicles is vital if global CO2 emissions are to be drastically cut. It is possible that a firm can find a way of lowering its cost structure over time. One way might be by increasing the amount of capital used relative to labour, with a consequent increase in factor productivity. The use of robots in car assembly plants and computer-aided production methods are good examples of how costs can be reduced. Shape of the long-run average cost curve The long-run average cost (LRAC) curve shows the least cost combination of producing any given quantity of output. This is shown in Figure 34.10. The LRAC curve is a flatter U-shaped curve compared to the SRAC and is indicative of a firm experiencing falling long-run costs over time. Falling long-run average costs allow a firm to lower its price without sacrificing profit. Products such as laptops, digital cameras, iPhones and games consoles are examples where costs and therefore prices have fallen through competition and changing technology. Figure 34.10: The long-run average cost curve The shape of the LRAC is derived from a series of short-run situations, as shown in Figure 34.10. As output increases, so too does the scale of the firm’s operations. The LRAC is sometimes referred to as the ‘envelope curve’ as it envelops a series of SRAC curves. The SRAC curves just touch or are tangential to the LRAC as output increases. The LRAC curve is therefore the lowest possible average cost for each level of output where the factors of production are all variable. However, this does not mean that the firm is producing at the minimum point on each of its SRAC curves. The concept of the minimum efficient scale A firm that is producing at its optimum output in the short run and the lowest average cost in the long run has maximised its efficiency. This is known as the minimum efficient scale since it is the lowest level of output where average costs are minimised. In industries where the minimum efficient scale is low there will be a large number of firms. Where the minimum efficient scale is high, competition will tend to be between a few large players. The minimum efficient point of production in Figure 34.10 is at Q. 34.6 Internal and external economies and diseconomies of scale The shape of the LRAC is also used to explain economies of scale. A firm experiences economies of scale if costs per unit of output fall as the scale of production increases. This is shown by the downward sloping section of the LRAC curve in Figure 34.10. If a firm gets increasing returns from using its factors of production, then it can produce more goods with smaller quantities of the factors of production. This means the firm is producing at a lower average cost. Specialisation and the division of labour (see Section 3.3) are an obvious source of economies of scale as workers become increasingly efficient in the tasks that they carry out. A production line in a food processing factory is a good example of where a group of workers contribute one part of the food production process. The shape of the LRAC slopes upwards after the minimum point. The reason for this is that beyond a certain size, a firm’s costs per unit of output may increase as the scale of output continues to increase. This situation is one of diseconomies of scale. Figure 34.11: A food production line TIP You should notice how ‘scale’ is used to explain the production and cost concepts when looking at the long run. This is because in the long run all factors of production are variable and so the scale of output can be increased. A common mistake is to confuse this with diminishing returns, which is a short-run concept and applies when just one factor of production is variable. Economies of scale and decreasing average costs Economies of scale occur when average costs decrease as the firm increases its output by increasing its size or scale of operations. Economies of scale can only accrue to a firm in the long run. Internal economies of scale are the benefits gained by a firm as a result of its own decision to produce on a larger scale. They occur because the firm’s output is rising proportionally faster than the inputs, which means that the firm is getting increasing returns to scale. If the increase in output is proportional to the increase in inputs, the firm will get constant returns to scale and the LRAC will be horizontal. If the output is less than proportional, the firm will see diminishing returns to scale or diseconomies of scale. Diseconomies of scale are represented in Figure 34.10 by any point on the LRAC curve beyond the minimum point. The advantage for a firm in benefiting from economies of scale is a reduction in the long-run average cost as the scale of output increases. This can occur in various ways: • Technical economies refer to the advantages gained directly in the production process through more efficient production methods. Some production techniques only become viable beyond a certain level of output. Vehicle production is the result of various assembly lines. The number of finished vehicles per hour is limited by the speed of the slowest sub-process. Firms producing on a larger scale can increase the number of slow-moving lines to keep pace with the fastest, so that no resources are standing idle and the flow of finished products is higher. • Purchasing economies: As firms increase in scale, they increase their purchasing power with suppliers. Through bulk buying, they are able to purchase supplies more cheaply, so reducing average costs. One of the best examples of this is the US retail giant Walmart, which uses its huge purchasing power to buy goods for its stores at the lowest prices. All major retailers behave in this way. Purchasing economies can also be made where a retailer reduces the number of items it sells. This allows the firm to concentrate on selling a more limited range of goods which can be bought in bulk at discounted prices. • Marketing economies: Large-scale firms are able to promote their products and pay lower rates for advertising on television, in newspapers and on social media because they are able to purchase large amounts of air time and space. This broad type of economies of scale includes savings in logistics costs (the cost of moving goods from where they are produced to where they are finally sold). Transport and warehousing costs can be reduced where customers require these services on a large scale. Another example is how large-scale firms can make savings through their IT systems. Examples include search engines and corporate websites where customers can buy a wide range of items such as insurance, hotel accommodation and airline tickets. The cost savings through efficient IT systems also contributes to the success of huge on-line retailers such as Alibaba and Amazon. • Managerial economies: In large-scale firms, managerial economies come about as a result of specialisation. Experts can be hired to manage operations, finance, human resources, sales, IT systems and so on. For small firms, these functions often have to be carried out by a multi-task manager. Cost savings are expected to accrue where specialists are employed. • Financial economies: Large-scale firms usually have better and cheaper access to borrowed funds than smaller firms. This is because the perceived risk to the lender is lower. KEY CONCEPT LINK Time: The benefits from economies of scale can give firms a longrun competitive advantage in the market. External economies of scale External economies of scale are particular benefits received by all the firms in an industry as a direct consequence of the growth of that industry. External economies of scale may be one reason for the trend towards the concentration of rival firms in the same geographical area. Figure 34.12 shows how external economies of scale can reduce longrun average costs for all firms in an industry. The advantages may include the availability of a pool of skilled labour or a convenient supply of components and services from specialist producers that have grown up to provide for all firms in that area. All firms may further benefit from greater access to knowledge and research; better transport infrastructure can come from the general expansion of firms and can result in lower logistics costs for all firms. Silicon Valley in California is a typical example as is Guzhen, China’s ‘lighting capital’. Another example is Cambridge, UK, where there is a concentration of biotech and electronics firms, many of which have research and development links with the University of Cambridge. Figure 34.12: External economies of scale and the long-run average cost curve Diseconomies of scale It should be made clear that there are limits to economies of scale. As indicated in Figure 34.10, a firm can expand its scale of output too much, with the result that average costs start to rise; efficiency is therefore compromised. This is indicative of diseconomies of scale. The most likely source of diseconomies of scale lies in the problems of management co-ordination of large complex organisations and the effect that size and poor communications have on the morale of the workforce. This is one important reason why, after a period of growth, a firm may decide to split its business into two standalone companies. Another example of diseconomies of scale is where workers may feel a lack of motivation due to the repetitive nature of the work they are carrying out. Workers might also feel that they are just a small insignificant part of a big organisation where senior managers do not appear to have a duty of care to employees. Although not particularly visible, these are underlying reasons for an increase in costs as the firm expands its scale of operations. In the same way as internal diseconomies of scale are possible, the excessive concentration of economic activities in a narrow geographical location can also have disadvantages. External diseconomies may be seen in the form of: • traffic congestion which increases distribution costs • land shortages and therefore rising fixed costs • shortages of skilled labour and therefore rising variable costs. ACTIVITY 34.4 Have economies of scale grounded the A380? Figure 34.13: The interior of an Airbus A380 The Airbus A380 is a double-deck, wide-body jet manufactured by the Anglo-French Airbus Corporation. It is the world’s largest passenger aircraft with a maximum capacity of 853 passengers in a single class configuration or 525 passengers in the more conventional three-class configuration. The aircraft’s four engines are quieter and at the time it started service, were more fuel efficient compared to the aircraft it is replacing, notably the ageing ‘Jumbo Jet’ Boeing 747s. There seemed to be a clear opportunity for airlines to benefit from economies of scale, particularly on busy routes where this aircraft could replace two smaller ones. Facing a near-empty order book and with extensive sales of Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner (maximum capacity 336 passengers) showing no sign of slowing, Airbus announced in February 2019 that it was to cease production of the A380. The A380 was designed to carry large numbers of passengers based on a ‘hub and spokes’ model; smaller aircraft would then be used to distribute passengers from the hub to other destinations as required. The problem is that the airline business has changed since Singapore Airlines had its inaugural A380 flight in 2007. The global recession has put a lot of pressure on airlines to be more efficient, particularly in their use of fuel, and for manufacturers to be more innovative in aircraft design. The new generation of long haul aircraft like the Dreamliner and the Airbus 350 has taken over the market. It might appear that economies of scale have killed off the A380. 1 Explain the likely types of economies of scale that might be gained by airlines that operate A380s. 2 How might these airlines and their customers benefit from economies of scale? 3 In a group, discuss whether economics has grounded the A380? Make a podcast of your discussion using a recording device such as a smartphone. One member of the group should introduce the topic under discussion. REFLECTION How would you explain to another learner the many applications of the concept of economies of scale? What evidence would you need to investigate whether a firm is benefiting from economies of scale? 34.7 Total, average and marginal revenue Revenue is the payment firms receive when they sell the goods and services that they have produced. Revenue is sometimes referred to as sales. Revenue is usually expressed over a time period such as a month or year. There are three revenue concepts: • Total revenue (TR) represents the sales of a firm and is obtained by multiplying the price of a good (P) by the number of units sold (Q): TR = P × Q • Average revenue (AR) is the revenue per unit of output sold: TR AR = Q • Marginal revenue (MR) is the additional revenue arising from the sale of an additional unit of output: ΔTR MR = ΔQ In analysing a firm’s revenue, it is important to know the type of market in which the firm is operating. In a fully competitive market the firm has no control over the price of its goods. The firm is a price taker. The firm’s demand curve will be horizontal and its revenue will depend entirely on the amount of goods sold. The market demand curve though will be downward sloping as shown in Figure 34.14. Figure 34.14: Price for a price-taking firm: a Market b Firm In any other type of market the firm will face a downward sloping demand curve. The firm is a price maker. If the firm chooses to increase output, price will fall; if it decides to reduce output, price is expected to increase. As output changes so does price and revenue. The extent of the change in revenue will depend on the price elasticity of demand. The firm’s demand curve is its average revenue curve. Marginal revenue will always be below average revenue since the firm can only sell more goods by reducing price. This is shown in Figure 34.15. Figure 34.15: AR and MR for a firm with a downward sloping demand curve 34.8 Normal, subnormal and supernormal profit Very simply, profit is what is left over when total costs are deducted from total revenue. The economist’s view is rather wider than the view of an accountant since the accountant’s approach does not fully recognise the full private costs of economic activity. As well as money paid out to factors of production, there must be an allowance for anything owned by the entrepreneur and used in the production process, such as any loans, that may have been made available to the business. This factor cost must be estimated and included with other costs. The concept of opportunity cost is relevant. The entrepreneur may have capital that could have been used elsewhere at no risk and this would have earned an income. So, this cost needs to be taken into account. An entrepreneur, therefore, will expect a minimum level of profit to reflect what could have been earned elsewhere with the resources that are available. In economics, this is known as normal profit. It is the entrepreneur’s reward as a cost of production because without it, nothing would be produced by the firm. It is therefore the minimum return that a firm must receive to remain in business. Crucially, normal profit is included in the total costs of a firm: Profit = Total revenue – total costs, including normal profit Any profit over and above normal profit is known as supernormal profit: Supernormal profit = Total profit – normal profit Where supernormal profits are being earned this is a signal for more firms to enter a market. Subnormal profit is when the profit that is earned by a firm is less than normal profit. Its significance is that if a firm is making subnormal profit then it may decide to withdraw from a market in the long run. TIP Learners often forget that normal profit is an item in the total costs of a firm. If a firm is not earning normal profits in the long run, then it should exit the industry. THINK LIKE AN ECONOMIST Who benefits from your daily cappuccino? Figure 34.16: Coffee shops are popular places to work and socialise Sales of coffee in specialist shops such as Costa, Starbucks and others continue to grow in many countries. Drinking coffee in such outlets has become a social experience. Coffee shops also offer a workspace with free wi-fi. Some customers may spend two to three hours drinking a coffee. This may be good value for the customer, but is less so for the retailer. Table 34.3 shows the cost structure of a large cappuccino with a retail price of £2.60 in the UK. Price (£) Coffee 0.09 Milk 0.09 Cup, lid and stirrer 0.19 Staff costs 0.63 Overheads 0.76 Profit 0.32 Sales tax (VAT) 0.52 Table 34.3: Cost structure of a large cappuccino in the UK It is not well known that the cost of the coffee is less than 4% of the retail price and that when the cost of milk is added, the cappuccino costs less than the cost of the disposable cup, lid and stirrer. 1 In a group, suppose you decide to lease a premises to open your own coffee shop. Use the information above to consider whether you as the owners are likely to benefit. Or will the owners of the premises benefit? Consider also how the coffee growers might benefit? Make a list of all the possible beneficiaries. Then try to put the beneficiaries in rank order.