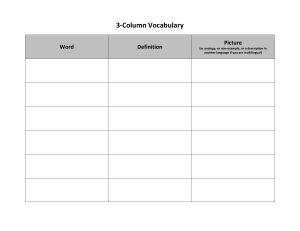

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316100069 Bilingual and Multilingual Education: Overview Chapter · November 2012 DOI: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0780 CITATIONS READS 17 25,642 1 author: Jasone Cenoz Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea 205 PUBLICATIONS 10,636 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Jasone Cenoz on 26 October 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Bilingual and Multilingual Education: Overview JASONE CENOZ Introduction Multilingualism is common in modern society due to different historical, social, political, and economic reasons. The beliefs, attitudes, and discourses of different societies are reflected in educational planning and specifically in language planning at school. Nowadays an increasing number of schools have multilingualism as one of their educational aims. Due to the international spread of English, education often aims at teaching English but also includes national languages and minority languages. Languages are learned, maintained, and reinforced through education. Schools can provide ample opportunities for the development of multilingualism because of the number of hours and years that children spend at school (Baker, 2007). Many schools all over the world include more than one language in the curriculum either as school subjects or as languages of instruction. Learning foreign languages has a long tradition as part of elite education and modern languages such as English, French, or German have been taught along with other school subjects. Classical languages, such as Latin and Greek, are also part of the school curriculum in some countries. The teaching of foreign languages has spread to general education in many countries and English and in some areas French are the main languages of instruction in many former colonial countries in Africa and Asia. In these settings, English and French are associated with more prestige and Western society than African and Asian languages. Bilingual and multilingual education also refers to learning languages that have a weaker social status. This weaker status may be reflected in the limited number of speakers of the so-called minority languages (e.g., Frisian in the Netherlands or Navajo in the United States), or in their limited functions in society (e.g., Quechua in Peru or Berber in Morocco) even when the demography is strong. Most research on bilingual and multilingual education has been carried out in Europe and North America but more recently Africa, Latin America, and Asia are also attracting more attention (De Mejía, 2005; Feng, 2007; Heugh & Skutnabb-Kangas, in press). In this entry we look at different aspects of bilingual and multilingual education. First, the meaning of multilingual education as related to bilingual education and its scope are addressed. Then the diversity of multilingual education and the continua of multilingual education as a tool to compare multilingual programs are discussed. The next section, “The Outcomes of Multilingual Education,” looks at the linguistic and cognitive effects of multilingual programs and “New perspectives in Multilingual Education” deals with new ways of communicative interaction among multilinguals and their challenges for multilingual education. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, Edited by Carol A. Chapelle. © 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Published 2013 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0780 2 bilingual and multilingual education: overview The Scope of Multilingual Education Multilingual education refers to the use of two or more languages in education provided that schools aim at multilingualism and multiliteracy. This definition focuses on the aims of education and considers the goals of multilingualism and multiliteracy as a requirement. Therefore, multilingual education does not include situations in which bilingual and multilingual children speak languages other than the school language at home but do not get any support for their home languages at school. This is a very common situation in different parts of the world including the United States and Western Europe where many immigrant schoolchildren speak languages that are not part of the school curriculum. We understand multilingual education (“multi” = many) as an umbrella term that includes bilingual education (“bi” = two) as its most common type but also refers to other types of multilingual education with three or more languages. Although trilingual education (or other forms of multilingual education with even more languages) is not as common as bilingual education, it can be found in different parts of the world (see Cenoz, 2009, chap. 2). In this entry we use “multilingual education” as a general term referring to two or more languages and we use “bilingual education” when referring specifically to two languages. Definitions of bilingual education tend to consider the use of two languages as media of instruction, that is, the teaching of subject matter content in two languages, as a characteristic of bilingual education (Baker, 2007, p. 131; Skutnabb-Kangas & McCarty, 2008, p. 4; Cummins, 2008a, p. xiii; May, 2008, p. 20). For example, the different types of immersion programs in Canada use both French and English as languages of instruction at least at some point. However, there can be bilingual education programs in which only one language, the minority language is used as the language of instruction and the majority language is used as a subject. This is the case in some European programs in the Basque Country or Wales where the use of Basque or Welsh as the language of instruction counterbalances the low vitality of the minority language as compared to the vitality of Spanish or English. In these cases, it does not seem to be necessary to use the majority languages as languages of instruction because there is enough exposure to them outside the school and the majority languages are also taught as school subjects. These programs result in a more balanced bilingualism than when both the majority and the minority languages are used for the same amount of time in the school curriculum (Cenoz, 2009). When more than two languages are involved, it is more difficult to use all the languages as languages of instruction even if the school aims at developing multilingualism and multiliteracy. Examples of multilingual education such as the European schools do not usually have three languages as languages of instruction but only two plus one or more languages as school subjects. Among the schools that can be considered multilingual because they aim at multilingualism and multiliteracy, some of them call themselves “trilingual” because they aim at developing communicative skills in three languages. There is a great diversity of schools regarding not only the languages of instruction used at school but also their target population. For example, in the Basque Country there are different programs aimed at the whole population with either Basque or Spanish as the language of instruction and in all of them English is a third language that can be taught as a subject or as additional language of instruction. Some trilingual schools are more elitist and are particularly aimed at expatriates and children of the upper classes as is the case of some international trilingual schools with languages such as Arab, French, and English in Arabic countries. The great diversity of multilingual schools regarding the languages involved, the target population, and the use of the languages both as languages of instruction and school bilingual and multilingual education: overview 3 subjects makes it difficult to establish fixed categories. In fact, it is even difficult to establish hard boundaries between bilingual schools where a third or fourth language is taught and schools that call themselves trilingual or multilingual. Types of Multilingual Education There are many different types of bilingual and multilingual education and Mackey (1970) already categorized 250 types of bilingual education. This diversity is related to the number of educational, linguistic, and sociolinguistic factors affecting multilingual education. According to the linguistic background of the students and the aims of the school some broad categories have been distinguished: transitional, maintenance, and enrichment programs (see for example May, 2008; Baker, 2011). Transitional programs aim at language shift from the child’s first language to the majority language and imply cultural assimilation. According to our definition of multilingual education transitional programs cannot be considered examples of multilingual education because they do not aim at multilingualism and multiliteracy. In the case of maintenance and enrichment programs the second language does not replace the first. Furthermore, enrichment programs aim at developing linguistic diversity. Baker (2011, chap. 10) proposes a very well known typology that distinguishes strong and weak forms of bilingual education taking into account the language background of the child, the language of the classroom, and the linguistic, societal, and educational aims. Weak forms of bilingual education are not included in our definition of multilingual education because their goal is monolingualism or limited bilingualism. Strong forms of bilingual education include immersion for speakers of the majority language, maintenance/ heritage-language programs, two-way/dual-language programs, and mainstream bilingual education in two majority languages for speakers of majority languages. Typologies of bilingual education cannot always fit all the diverse types and specific cases found in schools in different parts of the world. This is even more difficult when educational programs go beyond two languages and aim at developing communicative competence in three or more languages. As an alternative, Cenoz (2009) proposes the “continua of multilingual education” as a more appropriate tool to deal with the diversity of multilingual education. Hornberger (2003, 2008) applied the idea of continua to biliteracy by using two-way arrows to represent “infinity and fluidity of movement” (Hornberger, 2008, p. 277). This idea of continua is used in the “continua of multilingual education” so as to provide a tool that can describe as many situations of multilingual education as possible. As can be seen in Figure 1, the model places the educational continua inside a triangle because they are central to definining a school as multilingual. These “school” continua are linked to other external continua: linguistic distance and the sociolinguistic context. When learning two or more languages the typological distance between the languages already known by the speaker (the first language/s or others) and the target language(s) can have an influence on the acquisition process (Cenoz, 2009). When languages are closely related to each other they tend to have considerable similarities in grammar, vocabulary or the phonological system. For example, Kowalski (2009, p. 175), an American multilingual speaker explains: “Once I was there, however, the language practically fell into my lap. For one thing, with Spanish and Latin already down, Italian fell in its turn like a domino.” Typological distance is a factor that has to be taken into account when analyzing different types of multilingual education, and languages are not only “related” or “unrelated” but there can also be different degrees in their relationship. For example Italian and English, being Indo-European languages, are more related to each other than to Japanese. The bidirectional continuum proposed in the continua of multilingual education for language distance can accommodate different combinations of languages. A school with Italian, 4 bilingual and multilingual education: overview LINGUISTIC DISTANCE SCHOOL SUBJECT LANGUAGE OF INSTRUCTION TEACHER SCHOOL CONTEXT MICRO MACRO SPEAKERS STATUS MEDIA LANDSCAPE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT PARENTS SIBLINGS PEERS NEIGHBORS Figure 1 Continua of multilingual education. Cenoz (2009) © Multilingual Matters English, and Japanese in the curriculum can be placed more toward the “more distant” end of the continuum than one with Italian, English, and French but more toward the “less distant” end of the continuum than one with English, Japanese, and Hebrew. Apart from linguistic distance, the sociolinguistic environment in which a bilingual or multilingual school is placed needs to be taken into account. At the macro level, we can consider the relative status and vitality of the languages used at school, spoken by the students in society at large, or both. Factors such as the number of multilingual speakers, the status of the different languages, or their use in the media and the linguistic landscape can affect motivation to learn languages. For example Wildsmith-Cromarty (2009, p. 102) refers to status when discussing her experience learning Zulu: “the African languages have, until recently, carried no status in political, judicial, or educational domains so that there was no real incentive to learn them as additional languages.” The sociolinguistic context where a multilingual school is located can be more or less multilingual. For example, a multilingual school in Argentina is more toward the “less multilingual” end of the continuum than a multilingual school in India. The languages used by schoolchildren at home with their parents, siblings or the extended family, their neighbors, and peers are also part of the sociolinguistic context at the micro level. This context can be more or less multilingual. For example, Fantini recollects his childhood as being more bilingual and according to the continua of multilingual education this situation would be more toward the multilingual end of this continuum than a child brought up in a monolingual home: “I know our Italian dialects were dominant in both the family and the neighborhood. I don’t remember anything specific about speaking Italian (or English, for that matter), but I know Italian was used as needed, otherwise English” (Fantini, 2009, p. 244). The educational variables are four continua: subject, language of instruction, teacher, and school context. Languages can be school subjects but also languages of instruction. A high number of languages in the curriculum and their use as languages of instruction bilingual and multilingual education: overview 5 place a school toward the multilingual end of the continuum. Other factors that can be considered when comparing multilingual schools are the intensity of language instruction, the age of introduction of the languages, or the integration of different languages in the curriculum. Teachers’ communicative skills in different languages also contribute to make a school more multilingual as well as their specific training for multilingual education. A final factor that is considered to be in the school context is the use of different languages when teachers, supporting staff, students, and parents communicate outside the classroom in informal conversations and meetings. Literacy practices and the linguistic landscape inside the classrooms and in the school are also part of the school context. A school would be more multilingual if more languages are used for these functions. Freedman (2009, p. 139) recalls a school that would be toward the multilingual end of the continuum, “the school had an inherent multicultural character. Perhaps two-thirds of the students and some of the teachers spoke an African language (or several), in addition to French.” The “continua of multilingual education” can be used to compare different types of multilingual education within a country or internationally. This model can be more appropriate than traditional typologies to accommodate the diversity of multilingual education because it takes into consideration the effect of different factors but it proposes continua rather than closed categories so as to allow for comparison among different educational programs. The Outcomes of Multilingual Education Multilingual education, understood as education that aims at multilingualism and multiliteracy, entails good linguistic and academic results. This is the case both for speakers of a majority language and speakers of a minority language (or a language of low status) provided that there is an adequate development of the first language (May, 2008; Baker, 2011). In general terms, research in immersion education for language-majority students has shown that students learn another language and acquire literacy skills at no cost to their overall academic achievement or their first language skills (see Baker, 2011). These results work for early total immersion but also for dual-language programs or two-way immersion programs, where students from language minority and majority backgrounds are in the same class and both languages are used as languages of instruction (Genesee & Riches, 2006). These results indicate that language-majority students who use the L1 on a daily basis outside school can have an L2 as a language of instruction at no cost for their L1 or for achievement in academic domains such as science, mathematics, and social studies. Proficiency in the L2 in immersion programs is higher in receptive skills than in productive skills. Students in early total immersion generally achieve higher levels of proficiency in the L2 than those in partial immersion but intensity of instruction also produces good results in some late immersion programs. In general terms, these results originally reported for Canadian immersion have been confirmed in other contexts (see May, 2008; see also immersion education). In the case of speakers of minority languages or languages of low status, multilingual education that aims at maintaining and developing the first language along with other languages is associated with the best results not only in the L1 but also in the L2 and other areas of the curriculum. For example, a meta-analysis of research studies on minority children in the US reported by Genesee and Riches (2006) shows that learners who receive some reading instruction in the L1 in the primary grades achieve, at least, the same level of performance and in some cases even a higher level of performance in L2 reading than learners of similar linguistic and cultural backgrounds who have only received initial 6 bilingual and multilingual education: overview literacy and instruction in English. López (2006) reports the successful transfer of key competences from indigenous first to the second language in Guatemala and Bolivia when first languages are used as languages of instruction. Good results in academic achievement and in classroom participation have also been reported (see, for example, López & Sichra, 2008). Mohanty (2006) points out that there are social psychological and educational benefits when the first language is maintained along with other languages in India (see also Young, 2009, on Macau). Heugh and Skutnabb-Kangas (in press) analyze several cases of multilingual education in countries such as Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Peru, India, and Nepal, and conclude that mother-tongue education assists the content learning of other subjects but also other languages. These positive outcomes of maintaining and developing a minority language or a language of lower status at school have been confirmed in research studies conducted in many other parts of the world in diverse sociolinguistic and educational settings (see, for example, Cenoz & Gorter, 2008; Cummins & Hornberger, 2008). New Perspectives in Multilingual Education Multilingual education aims at developing multilingualism and multiliteracy but very often creates strong boundaries between languages by associating different languages to different teachers (one teacher, one language) or to different spaces (one classroom for each language). However, multilinguals use their languages as a resource and often mix them in daily communication with other multilinguals. The influence of some teaching methods has created isolation between the different languages in most school contexts but the interaction between the languages can be helpful in different ways (Cummins, 2008b). For example, multilingual students can use the languages they know to develop their metalinguistic awareness and make more progress when learning additional languages (Jessner, 2006). Nowadays, there is a trend toward a more multilingual approach in multilingual education, an approach that does not isolate languages. For example, Blackledge and Creese (2009) advocate for the flexible use of languages in school environments in order to focus on the speakers and not the languages and to look at their linguistic practice as related to the context in which they take place. In the same vein, García (2009) considers that pedagogical practices have to be built on the multimodal literacy practices that children bring to school and not on separate codes. In fact, new technologies have influenced communication and nowadays multimodality is increasingly important. Furthermore, elements from different languages are combined with other semiotic elements such as images, icons, or pictures. These networks of communication together with linguistic and cultural diversity in school settings pose new challenges for multilingual education. SEE ALSO ON BILINGUAL AND MULTILINGUAL EDUCATION: Assessing Multilingualism at School; Attitudes and Motivation in Bilingual Education; Baetens Beardsmore, Hugo; Baker, Colin; Bilingual Education and Immigration; Cenoz, Jasone; Clyne, Michael; Content and Language Integrated Learning; Cultural Awareness in Multilingual Education; Cummins, Jim; Curriculum Development in Multilingual Schools; Early Bilingual Education; Ecology and Multilingual Education; Edwards, John; Edwards, Viv; Elite/Folk Bilingual Education; Empowerment and Bilingual Education; Fishman, Joshua A.; García, Ofelia; Genesee, Fred; Gorter, Durk; Heller, Monica; History of Multilingualism; Hornberger, Nancy H.; Martin-Jones, Marilyn; Materials Development for Multilingual Education; May, Stephen; McCarty, Teresa L.; Minority Languages in Education; Mohanty, Ajit; Mother-Tongue-Medium Education; Multilingual Education and Language Awareness; Multilingual Education in Africa; Multilingual Education in Australia; Multilingual Education in China; Multilingual Education in Europe; Multilingual Education bilingual and multilingual education: overview 7 in India; Multilingual Education in Latin America; Multilingual Education in North America; Multilingual Education in the Arab World; Multilingual Identities and Multilingual Education; Multilingualism and Higher Education; Multiliteracies in Education; Romaine, Suzanne; Shohamy, Elana; Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove; Spolsky, Bernard; Teacher Education for Multilingual Education; Williams, Colin H. SEE ALSO: Code Mixing; Code Switching; Language Planning and Multilingualism; Language Policy and Multilingualism; Multilingualism; Multilingualism and Metalinguistic Awareness References Baker, C. (2007). Becoming bilingual through bilingual education. In P. Auer & L. Wei (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication (pp. 131–52). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters. Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2009). Multilingualism: A critical perspective. London, England: Continuum. Cenoz, J. (2009). Towards multilingual education: Basque educational research from an international perspective. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters. Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (Eds.). (2008). Applied linguistics and the use of minority languages in education (Special issue). Aila Review, 21. Cummins, J. (2008a). Introduction to volume 5: Bilingual education. In J. Cummins & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 5: Bilingual education (pp. xiii–xxiii). New York, NY: Springer. Cummins, J. (2008b). Teaching for transfer: Challenging the two solitudes assumption in bilingual education. In J. Cummins & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 5: Bilingual education (pp. 65–75). New York, NY: Springer. Cummins, J., & Hornberger, N. (Eds.). (2008). Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 5: Bilingual education. New York, NY: Springer. De Mejía, A. M. (Ed.). (2005). Bilingual education in South America. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters. Fantini, A. E. (2009). Expanding languages, expanding worlds. In E. Todeva & J. Cenoz (Eds.), The multiple realities of multilingualism (pp. 243–63). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. Feng. A. (Ed.). (2007). Bilingual education in China. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters. Freedman, S. (2009). A life of learning languages. In E. Todeva & J. Cenoz (Eds.), The multiple realities of multilingualism (pp. 1–32). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. García, O. (Ed.). (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell. Genesee, F., & Riches, C. (2006). Literacy: Instructional issues. In F. Genesee, K. Lindholm-Leary, W. M. Saunders, & D. Christian (Eds.), Educating English language learners: A synthesis of research evidence (pp. 109–75). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Heugh, K., & Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (Eds.). (in press) Multilingual education works: From the periphery to the centre. New Delhi, India: Orient BlackSwan. Hornberger, N. (Ed.). (2003). Continua of biliteracy: An ecological framework for educational policy, research and practice in multilingual settings. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters. Hornberger, N. (2008). Continua of biliteracy. In A. Creese, P. Martin, & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 9: Ecology of language (pp. 275–90). New York, NY: Springer. Jessner, U. (2006). Linguistic awareness in multilinguals. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. 8 bilingual and multilingual education: overview Kowalski, C. (2009). A “new breed” of American? In E. Todeva & J. Cenoz (Eds.), The multiple realities of multilingualism (pp. 171–89). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. López, L. E. (2006). Cultural diversity, multilingualism and indigenous education in Latin America. In O. García, T. Skutnabb-Kangas, & M. E. Guzmán (Eds.), Imagining multilingual schools (pp. 238–61). Clevedon, England: Multillingual Matters. López, L. E., & Sichra, I. (2008). Intercultural bilingual education among indigenous peoples in Latin America. In J. Cummins & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 5: Bilingual education (pp. 295–309). New York, NY: Springer. Mackey, W. F. (1970). A typology of bilingual education. Foreign Language Annals, 3, 596–608. May, S. (2008). Bilingual/immersion education: What the research tells us. In J. Cummins & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 5: Bilingual education (pp. 19–34). New York, NY: Springer. Mohanty, A. K. (2006). Multilingualism of the unequals and predicaments of education in India: Mother tongue or other tongue. In O. García, T. Skutnabb-Kangas, & M. E. Guzmán (Eds.), Imagining multilingual schools (pp. 262–83). Clevedon, England: Multillingual Matters. Skutnabb-Kangas, T., & McCarty, T. (2008). Key concepts in bilingual education: Ideological, historical, epistemological and empirical foundations. In J. Cummins & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 5: Bilingual education (pp. 3–17). New York, NY: Springer. Wildsmith-Cromarty, R. (2009). Incomplete journeys: A quest for multilingualism. In E. Todeva & J. Cenoz (Eds.), The multiple realities of multilingualism (pp. 93–114). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. Young, M. Y. C. (2009). Multilingual education in Macau. International Journal of Multilingualism, 6, 412–25. Suggested Readings Cenoz, J. (Ed.). (2008). Teaching through Basque: Achievements and challenges. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters (Also special issue of Language, Culture and Curriculum, 21). García, O., & Baker, C. (Eds.). (2007). Bilingual education: An introductory reader. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters. Helot, C., & De Mejía, A. M. (Eds.). (2008). Forging multilingual spaces: Integrated perspectives on majority and minority bilingual education. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters. Schechter, S. R., & Cummins, J. (Eds.). (2003). Multilingual education in practice: Using diversity as a resource. London, England: Heinemann. Skutnabb-Kangas, T., Phillipson, R., Mohanty, A. K., & Panda, M. (Eds.). (2009). Social justice through multilingual education. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters. View publication stats