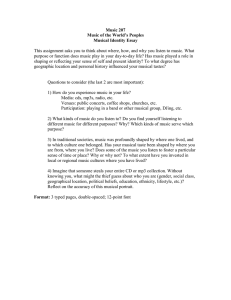

Review

Reviewed Work(s): Companion to Contemporary Musical Thought by John Paynter, Tim

Howell, Richard Orton and Peter Seymour

Review by: Nicholas Cook

Source: Music & Letters, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Feb., 1994), pp. 115-120

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/737269

Accessed: 19-01-2024 23:34 +00:00

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Music & Letters

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

sociation of experience caused by the unresolved

panorama of world musical history, charting the

tensions between art and social reality finds a

rise of individual consciousness in the music of the

strong Bergian pre-echo, according to Adorno, in

tonal era, and its subsequent collapse into the

the major-minor polarities (as well as stylistic in-

reborn tribalism of the global village. In the un-

congruities) of Mahler's alienated diatonicism.

fashionable boldness of its vision, its fine

Furthermore, their shared devotion of self-

disregard for the conventions and limitations of

abnegation is seen in sharp contrast to the

professional musicological writing, Mellers's

Wagnerian persona of apostate rebel. The goal of

opening contribution appropriately sets the tone

emancipation is also common to both, even while

of the Companion as a whole.

it remains shackled to determinate contradiction;

By far the most coherent of the four sections is

thus the final work Adorno addresses, Lulu, is en-

'The Technology of Music'. Among the best ar-

capsulated as the 'union of suppression with hope'

ticles are those that link technology with the

(p. 131). The dissolution of self, like the dissolu-

aesthetic and philosophical concerns that lead

tion of history for which it is the dispassionate

composers to use it. Curtis Roads's 'Composition

figure, is ultimately conditioned by temporality.

with Machines', for instance, talks lucidly about

This course of departure, of extinction, is given

the considerations that led him to move away

public and private expression by Mahler and

from writing comnposition-specific programs to

Berg respectively in two lyric-dramatic sequences:

creating interactive composition environments;

Das Lied von der Erde and the Lyric Suite. In

he doesn't so much explain the technology as ex-

Mahler's song cycle, the farewell gaze towards

plain what makes him want to use it. Again, in

vanishing reality is accompanied by a sixth chord;

'Electroacoustic Music and the Soundscape: the

in Berg's quartet the absence/sense of an ending

Inner and Outer World', Barry Truax argues that

is accomplished by an oscillating D b -F disappear-

the technique of granular synthesis may help

ing into infinity. That the Violin Concerto should

composers to break out of the alienated world of

in turn represent an absent presence with respect

'concert music' and so bring about Attali's 'age of

to this book seems entirely appropriate. For as

composition'; as Truax puts it, 'what is significant

Adorno would have sensed, its closing reprise

about the composer's use of technology is its

of Mahler's sixth chord ultimately transcends

ability to change the process of compositional

the limits of personal association to form an

thinking, not merely its output'.

Just as imaginative, but making fewer demands

eternal after-image of ephemerality within the

on the reader's technical knowledge, is Craig

administered world.

ALAN STREET

Harris's unpromisingly titled 'Artistic Necessity,

Context Orientation, Configurable Space'. This

purports to show how you can use pen, paper and

a couple of easels to represent musical ideas from

Companion to Contemporary Musical Thought.

different angles and in different configurations.

Ed. by John Paynter, Tim Howell, Richard

But Harris's vocabulary tells another story: he

Orton & Peter Seymour. 2 vols. pp. xxxviii +

speaks of selecting, highlighting, dragging, and

621; x + [584]. (Routledge, London & New

zooming the images. At one point he even writes

York, 1992, ?150. ISBN 0-415-03092-7.)

'Save the current state of the room view'-

something that is hard to achieve with pen,

In two volumes and totalling over 1,200 pages,

paper and two easels! Without mentioning

the Companion to Contemporary Musical

computers, in fact without making any demand

Thought is a vast, sprawling tapestry of music-

whatever on his readers' technical knowledge,

related writing, a kind of musicological Hymnen.

Harris demonstrates the compositional potential

And like Hymnen, it is organized into four

of computers in representing, linking and

regions, each edited by a member of the Depart-

transforming musical ideas in an infinity of

ment of Music at York University: 'People and

aspects. There is just one point where he states

Music' (John Paynter), 'The Technology of Music'

the article's basic message in so many words: 'The

(Richard Orton), 'The Structure of Music' (Tim

notion of a single representation for a composi-

Howell) and 'The Interpretation of Music' (Peter

tion is obsolete'.

Seymour). Located outside the framework is a

The need for multiple views of music -not just

keynote address, so to speak, by Wilfrid Mellers,

for composition but, as Harris says, 'for perfor-

the department's founding professor; entitled

mance, conducting, music analysis, musicological

'Music, the Modem World, and the Burden of

research, and education'-is one of several motifs

History', its 21 pages offer a kaleidoscopic

that recur in this section of the Companion.

115

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

(Roads, for example, says the same thing.) Other

no cultural analysis of music in the age of

such motifs include the limitations of real-time

mechanical reproduction; it doesn't touch on

synthesis (Peter Manning, Trevor Wishart and

music technology in the pre-electronic era.

Jean-Claude Risset all refer to this), the trade-off

Strictly speaking, even 'Technology and Composi-

between flexibility and cost, and-what amounts

tion' would be too broad a title, since it takes vir-

to much the same thing-the proper relationship

tually no account of commercial music. But then,

between the 'serious' composer and the burgeon-

if it had covered all these topics, the section

ing music industry. Here there are two articles

would have lost its focus -and that is largely what

that form an instructive contrast: Peter

gives it its value. Under a more appropriate title,

Manning's 'Towards a New Age in the Tech-

it could perfectly well have made a book in its

nology of Computer Music' and Richard Moore's

own right.

'A Technological Approach to Music'. Both are

The biggest problem with the other three sec-

essentially introductory, proceeding historically

tions of the Companion is that they lack focus. In

and drawing out significant developments and

the case of 'The Structure of Music', it is at least

issues. Manning's article is sensible, informative

obvious that considerable efforts have been made

and balanced, setting technological developments

to form the contributions into some kind of

into the context of their use. Moore's article

coherent sequence. An introductory article on

covers the same ground, but the tone is completely

musical meaning by Lorenz Reitan (which

different. He divides computer musicians into

manages not to mention any of the main English-

two camps: traditionalists (who want to 'absorb

language sources for this topic) is followed by

new technology into the pursuit of traditional

three articles on analysis. The first of these,

artistic goals') and revisionists, who want to

Jonathan Dunsby's 'Music Analysis: Commen-

'redefine artistic goals in terms of new possibilities

taries' (misprinted as 'Musical Analysis: Commen-

opened up by technological developments'. The

taries' in the table of contents), offers some

choice of terminology indicates the ideologically-

characteristically defensive ruminations on the

charged nature of Moore's approach (although, un-

integrity of the discipline; Dunsby is not sure

like in Maoist China, 'revisionist' turns out to be

that analysis can be justified on the grounds of

a term of approbation). By the end of the article,

contributing to either the enjoyment or the

Moore is telling us that synthesizers with auto-

understanding of music, and asks why it cannot

mated accompaniments are 'musically irrelevant'

be regarded as an 'activity that is its own reward'.

(my eight-year-old wouldn't agree) and that com-

Next, in 'Analysis and Psychoanalysis: Wagner's

mercial software packages like sequencers are 'the

Musical Metaphors', Christopher Wintle offers

logical equivalent of a sound recording'. By this

a series of close readings in which he uses

he means that using ready-made software is no

psychoanalytical terminology to draw out the

more creative than hitting the 'play' button on a

psychological implications of Wagner's music,

CD player; 'Any musician who wishes to use com-

suggesting at one point that the surface reflection

puters in a creative way needs to learn how to

of a middleground element in Die Walkure may

read and write computer programs just as much

signify that 'Sieglinde's anxiety has welled to the

as he or she needs to learn how to read and write

surface, and "worked itself out"'. (I hope that

music notation'. This is a kind of William Morris

isn't too simplistic a reading of Wintle.) Finally,

approach to technology; you might as well argue

Tim Howell, the section editor, contributes the

that if Chopin was to use the piano creatively, he

cleverly-titled 'Analysis and Performance: the

would have had to build his own instruments.

Search for a Middleground', in which he argues

Nevertheless, Moore is not the only person to

(following Dunsby) against too direct an iden-

think this way, and the contrast between his and

tification of the interests of analysts and

Manning's approach brings out the philosophical

performers.

issues behind the technology.

The next article, Robert Sherlaw Johnson's

The one criticism I would make of 'The

'Analysis and the Composer', forms a link to the

Technology of Music' is that it doesn't live up to

following two articles, which are about composi-

its title; it should really have been called

tion. Sherlaw Johnson's starting-point is that 'The

'Technology and Composition'. It doesn't cover

most important problem facing a composer in the

the special problems of analysing electronic and

formative stage is the ability to see behind the im-

computer music; it doesn't talk about reproduc-

mediate detail of the music to its behaviour at the

tion technology and its effect on social use of

background level'. Hierarchical conceptions of

music and the music industry; it has nothing on

music are useful, then, but those on offer-he

the media of musical dissemination; it offers

cites Schenker and Reti - are too constrained in

116

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

their presuppositions; what is needed instead is a

this slippery concept signifies, it surely revolves

kind of fuzzy hierarchy theory (the term is mine, around the product of music rather than its pronot SherlawJohnson's), and he gives some indica-

cess; and that means that it is difficult to explain

tions of what that might look like. Sherlaw

the inclusion within this section of articles on im-

Johnson is talking about composition, but he is

provisation, which specifically emphasizes process

using the language of analysis.

at the expense of product.

At this point, however, there is an abrupt

The remaining two sections are no less inclusive

change of tone. Jonathan Harvey's 'New Direc-

in scope. 'The Interpretation of Music' begins

tions: the Conception and Development of a

with a firm focus on performance practice; that is

Composition' has nothing to do with analysis as

what Peter Seymour talks about in his introduc-

commonly understood. It begins with an account

tion to the section. And Peter Williams's 'Perfor-

of the composition of his Bakhti, and ends by urgmance Practice Studies: Some Current Aping the need to move beyond the reifications of

proaches to the Early Music Phenomenon' charts

Western rationalism towards a spiritual, trans-

the development of the idea of interpretation in a

cendental art; 'It is only when one casts oneself

wonderfully graphic manner, focusing it round a

upon the All (by attaining to some degree trans-

Cistercian monk singing a Benedictine hymn;

cendental consciousness)', writes Harvey, 'that

Wilfrid Mellers's presentation of the same point

one can escape the limitations of society here

in the preceding chapter seems abstract and wordy

and now'. And the need to break out of our self-

by comparison. (Mellers is one of just three con-

imposed limitations is also the topic of the follow-

tributors with two articles; the remaining 50 have

ing article, 'Morty Feldman is Dead' by James

one apiece). Then Williams sets up an issue that,

Fulkerson. As the title indicates, this begins as a

predictably, resonates through the other articles

meditation on Feldman, but it turns into an at-

in this section: the extent to which historical

tack on the 'New Complexity', which Fulkerson

knowledge should be tempered by musical intui-

describes as 'a new musicaficta'.

tion. Duncan Druce ('Historical Approaches to

In line with the best compositional models, the

Violin Playing') and Klaus Neumann ('Producer

pace of change now quickens. Richard Orton's

for Early Music: a Cog in the Mechanism of

'From Improvisation to Composition' (which is

Musical Life') affirm what has more or less

mainly an account of MIDIGRID, a software

package developed at York) forms a second

become received wisdom: historical knowledge

can only take you so far, and at its limits you must

bridge, linking composition with improvisation.

trust to innate musicality.

And Eric Clarke's 'Improvisation, Cognition, and

What does Williams think? He begins by

Education' forms yet another bridge, this time

quoting Richard Taruskin's statement that a per-

between improvisation and psychology; this leads

formance bereft of intuition is 'not a performance

to a literature review by John Sloboda ('Psycho-

but a documentation of the state of knowledge'.

logical Structures in Music: Core Research 1980-

But he turns this to polemical effect. 'For a per-

1990'), which itself leads to George Pratt's 'Aural

former merely to "document the present state of

Training: Material and Method'. The section

knowledge" is by no means a ridiculous idea', he

concludes, by way of coda, with two articles that

says, 'for who is to say what is a convincing, definihave no obvious links with anything else: 'Aspects

tive, artistic performance? . . . As music-studies

of Melody: an Examination of the Structure of

learn to avoid the quick performance practice

Jewish and Gregorian Chants' by Yehezkel Braun, answers, it will become a high ideal to use the

and 'Music, Number and Rhetoric' by John

concert area as a place to "document the state of

Stevens.

knowledge", for true knowledge might increas-

All this amounts to a valiant attempt to impose

ingly be seen as a better goal than concert-hall

some kind of logical ordering upon a set of ar-

entertainment.' His essential position is, in fact,

ticles that have no real unity of subject matter,

similar to the Dunsby-Howell one on analysis and

purpose or level. To be sure, all of them have

performance: historical study and performance

something to do with 'The Structure of Music';

are essentially different disciplinary specialisms.

but then that would apply to many of the articles

Thus 'To link studies directly to performance is

in other sections too. It is simply too broad a field

not only a distortion of a noble aim but is itself an

to be coherent, at least without some kind of inanachronism . . . [Historical study] is quite

troductory framework or overview. In his general

distinct from preparing concerts, which is prepareditor's introduction to the Companion as a

ing a public show and forcing one to be decisive

whole, John Paynter says that the focus of this in

secmany unclear areas, "interpreting" in order to

tion is 'the "art objects" themselves'. Whatever

"communicate", rushing to judgement when con-

117

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

templative study is the more instructive by

The same applies, only more so, to the re-

nature.' In this way the real value of performance

maining (actually the first) section, 'People and

practice studies is not that they tell performers

Music'. Again, this title could be understood

what to do but that they'lead [them] to recognize

more or less inclusively. In its most inclusive

the leap of conjecture their performance

sense, it would include everything that pertains to

represents'.

music; to adapt the classic quip on folk song, 'All

The ensuing articles fit more or less into the

music is people music; I never heard a horse sing'.

performance practice framework, though with

In its most specific sense, it would refer to the

varying emphasis. Anthony Rooley (another of

relationship between musical and social struc-

the contributors with two articles) emphasizes the

tures; just one article deals with this, John

passionate nature of Renaissance performance,

which aimed (as Ficino put it) to instil 'divine

argues against seeing music as a reflection of

Shepherd's 'Music as Cultural Text'. Shepherd

frenzy' in the listener. Rogers Covey-Crump

society; rather, he says, music is an integral part

discusses tuning in vocal consort music, and John

of society. And he goes on to refine the rather

Bryan reconstructs the history of the English

fragile arguments about the homology of musical

consort-anthem; both articles are suffused with

and social structures that he originally presented

the experience of period-style performance.

as long ago as 1977 in another collection based on

Alison Wray offers a guide to authentic

York, Whose Music? A Soczology of Muszcal

pronunciation.

Languages. If this section had been intended as a

But as the section proceeds, articles appear

focused treatment of the relationships between

that have no discernible application to perfor-

music and society, Shepherd's article could have

mance. Graham Dixon's 'Liturgical Considera-

provided a useful introductory framework for it.

tions: an Apologia and Some Guidelines' attempts

As it is, however, Shepherd's article is posi-

to reconstruct the period context of liturgical

tioned half-way through the section, and it is

performance in the Roman rite c.1700, with its

hard to find a common focus in the other articles.

complex choreography of ritual; such work is ob-

Murray Schafer presents his appealing, if familiar,

viously important to a critical understanding of

perspective on the soundscape; Hans-Werner

the surviving music, but it is hard to see how it

Heisler offers an Adornoesque diatribe against

could be applied in an actual performance situa-

the 'scented stench' of background music;

tion. Peter Holman's '"An Addicion of Wyer

Thomas Regelski attacks both what he calls the

Stringes beside the Ordenary Stringes": the

Activities Approach to musical education and

Origin of the Baryton' charts the early evolution

student-centred learning, instead arguing in

of the lyra viol in minute detail, mainly on the

basis of archival evidence; there is no discussion

of any actual music. Finally, in 'Lutoslawski and

Huray charts the emergence of passionate ex-

pressivity in music and other arts during the

a View of Musical Perspective', Philip Wilby con-

Renaissance; Ellen Harris discusses the reception

trasts moment-to-moment immersion in music

of Handel among his immediate successors, draw-

with formal perception of it, developing a rather

ing on Harold Bloom's concept of the 'Great

favour of Action Learning. The late Peter le

Schoenbergian view of repetition which he terms

Inhibitor'; Joscelyn Godwin argues that a

'musical perspective' and which he illustrates

through a discussion of music by Lutostawski.

speculative approach to music 'enables us to

perceive directly the numbers that are at the

This has nothing to do with performance practice. But then, the section is not called 'Perfor-

heart of manifestation'. Finally, a number of articles offer what might be most discreetly termed

'creative' perspectives on music that would not

have been out of place in Perspectives of New

mance Practice'; it is called 'The Interpretation

of Music', a term which can embrace any kind of

analytical or critical treatment of music as well as

its performance. Once again, then, the title turns

Edwin London's 'On Making Music out of Music')

out to be all-inclusive. The trouble is that, if it is

is representative:

intended in this extended sense, the contents

don't live up to it; eleven articles on performance

Music around 1980, of which the following (from

The sorest purposeful sage (Roget's Le roi d'Isness)

allow-lows those in show business debut to make Cnoh-te of La (ma-mer-ha-ya-na) sans tyne un-miked. In

practice, one on liturgical performance c.1700,

one on the development of the lyra viol, and one

uttered words if

on Lutostawski don't add up to any kind of

(Weber + n) = (Berlioz - lz),

coherent or balanced treatment of 'The Interpretation of Music'. Presumably they were never

does Shakespeare's comings (eek) obscure the circled

intended to.

eye shade of Carl Maria von Oberon?

118

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

after all, supposed to be a 'Companion to Con-

To which I can only reply, 'who knows?'

What is the reason for the strikingly loose

temporary Musical Thought'; the economic and

organization of this Companion? The answer is to

industrial context of musical production and con-

be found in Paynter's introduction, where he ex-

sumption, for instance, is represented by little

plains that the intention was to provide a

more than a few old-fashioned attacks on commer-

cross-section of the pragmatic and the speculative in a

particular area of experience at a given point . .. From

the start our principal aim has been to enable readers to

experience something of the attitudes of mind current

in musical scholarship and practice in the late 1980s

and early 1990s, and thereby to feel that they are part

of the debate. We asked ourselves the question: what is

it that those who, at this time, are most closely involved

cial exploitation and the use of the media for purposes of manipulation and repression. (You'd

never guess from reading this Companion that

there has been an explosion in the dissemination

of 'serious' music through news-stand magazines,

CD sales, and radio channels such as Classic FM.)

All this contributes to an impression of not being

with it think music is about? And to get the answer

quite in touch, or even perhaps of eccentricity,

we invited musicologists, music historians, sociologists

that I suspect will be all the stronger among the

and educationalists, composers, performers, producers,

analysts and critics from a variety of backgrounds in a

number of different countries to contribute articles on

Companion's North American readers.

What irritates me is not so much the Compa-

topics of their own choice [my italics], topics that were, nion itself; after all, why shouldn't the editors

therefore, of the utmost importance to the writers

themselves.

have their own perspectives on the study of music?

It's the publishers' hype. The sales brochure,

The editors didn't, then, begin with a list of

some of which is reprinted on the back covers of

topics; they began with a list of people.

the volumes themselves, describes the Companion

Now there are two points to be made about

as 'a comprehensive survey of current thinking

this. The first is that, if you want to provide a

about the study and practice of music . . . [that]

snapshot of a discipline in this way, what you

covers all major areas of debate and study'. But

need is a large number of brief contributions;

that is simply not true. And in fact Paynter him-

after all, you are trying to sample people's con-

self goes out of his way, in the introduction, to

cerns, and these can be expressed in a page or

avoid making any such claims: 'Naturally, we hope

two. (The colloquium on 'The Future of Theory'

that the range of topics and the extensive index

published in 1989 by the Indiana Theory Review

will make it a useful reference resource, but

is an example of such a snapshot.) What is

the book is not, and was never intended to be,

needed, in other words, is comprehensiveness of

encyclopedic'.

authorship, not comprehensiveness of treatment.

This is a telling remark, given that the book is

And that brings me to the second point: just how

part of a series called 'Routledge Companion En-

representative are the contributions to this Com-

cyclopedias'! What I think this reveals is a basic

panion of music-related scholarship as a whole?

confusion, or lack of agreement, on the part of

Obviously there is no point in pursuing this ques-

editors and publishers as to what the Companion

tion on an ad hominem basis; everybody would

is for and, more particularly, who it is for. The

come up with a different list of who they would

publishers, as you might expect, think it is for

have asked to contribute. But what one can

everybody: 'The scope of this musical compen-

reasonably comment on is the disciplinary

dium ensures its value as a companion to students,

coverage.

academics, professional musicians, critics and

It's not a matter of what the Companion con-

writers, and teachers of theory and practice. It

tains but of what it leaves out. Among the omis-

will be of great interest to all music-lovers and

sions are everything that pertains to what is often

anyone who is looking for something more than

called 'critical musicology', encompassing her-

dates and musical facts, and wants to be in touch

meneutics, narrativity, reception theory, gender

with what scholars, composers, and performers

and other minority issues. There is nothing on

think today about music.' The danger, of course,

historiography or source criticism. Apart from a

is that if you try to please everybody you end up

few casual references, there is nothing on popular

pleasing nobody.

music, ethnomusicology or issues of multicultural-

The most obvious symptom of the lack of a

ism. But these are some of the hottest topics in

clearly-defined target readership is the multipli-

musicology, if conference programmes, publica-

city of levels and tones of voice evident in the

tions and personal experience are anything to go

contributions. Some contributors offer carefully

by (and what else is there to go by?). Moreover,

balanced introductions to their fields (John

when topics of current concern do appear, the

Sloboda even adopts a quantitative criterion,

treatment sometimes seems dated for what is,

based on citations, to decide what music-

119

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

psychological research he will include); these

Schenker. (Schenker is quoted at one point, but

writers explain key terms and concepts as they

only via a citation from Joseph Kerman that does

proceed. Others offer personal views, assuming

not adequately represent Schenker's approach.)

the reader's prior familiarity with their topic.

Again, Joel Chadabe offers a graphic if brief

Then there are are state-of-the-art articles, which

account of M (the interactive composition/per-

could perfectly well have appeared in a learned

formance package from Intelligent Music, of

journal; this applies, for instance, to the con-

which Chadabe is president) but makes no refer-

tributions by Christopher Wintle, David Kershaw

ence to David Zicarelli's major article on the sub-

and Denis Smalley, all of which are best

ject in Computer MusicJournal; similarly, Curtis

understood in the context of other work in the

Roads writes on 'Composition with Machines' but

relevant field. The same is true of Thomas

never mentions David Cope's important and in-

Regelski's article, which is polemically directed at

teresting work. Now this is in no way a criticism

other music educationists; this leaves it rather

of these authors, whose contributions make

isolated in a collection in which music education

perfect sense considered in their own right. But it

is curiously under-represented, considering John

is a criticism of the way in which the Companaon

Paynter's pre-eminence in this field. Peter le

has been conceived, significantly limiting its

Huray's article reads rather like a lantern lecture

usefulness to a large number of readers.

for an adult education audience (and a very good

The Companion to Contemporary Musacal

one too). And finally, as I said, there are creative

Thought is an uneven production; there are good

perspectives of the Perspectives of New Music

articles and not-so-good ones. That could hardly

kind.

be avoided in a collection of this size and scope.

Of course there's a positive aspect to this; it all

The trouble is that they do not gel, because the

adds up to a panorama of the varied approaches

publication as a whole has not been adequately

to be found in the study of music today, and I

thought through in terms of its potential reader-

would certainly endorse Paynter's claim that the

ship. With the exception of 'The Technology of

collection has 'a certain roundness of sensibility in

Music', it does not amount to more than the sum

which more conventional "scholarly" approaches

of its parts.

to the subject are balanced with poetic and

NICHOLAS COOK

philosophical, but no less intensely musical, con-

tributions'. (This is largely because of the relative

Linguistics and Semiotics in Music. By Raymond

prominence of contributions by composers and

Monelle. pp. [xv] + 349. 'Contemporary

performers.) All the same, it makes it hard for the Music Studies', v. (Harwood Academic

user to know quite what he or she is meant to do

Publishers, Chur, Switzerland, &c., 1992,

with the Companion. If you read the whole thing,

$46/?25. ISBN 3-7816-5209-9.)

which is one of the ways Paynter suggest it can be

used, you will end up with a curiously skewed and

This handbook supersedes all earlier efforts to

provide a guide to the extraordinarily diverse

to that extent quite misleading impression of contemporary thinking about music. And you will

field of musical semiotics. In ten substantial

find that basic technical knowledge is assumed in

chapters, Raymond Monelle assembles a variety

some fields (such as analytical method) but not in

of approaches to musical study that, with greater

others (psychology of music, digital sound syn-

or lesser explicitness, reveal a semiotic orientathesis). If on the other hand you refer to the Com- tion. The result is a sometimes startling,

panion for an exposition of a particular topic

sometimes predictable juxtaposition of music(s)

(which is what its size and price will probably lead

and method(s). Folksongs, the 'Marseillaise',

most people to do), then you may or may not find

it there, and you may or may not find that it is

written at the right level for you; moreover, if

you want to research the subject further, you are

likely to find yourself hampered by the lack of a

properly structured bibliography.

As an illustration of this, Tim Howell's article

on analysis and performance is a perfectly effi-

cient and readable introduction to the basic

issues, but it will not lead you to the main writings in this area, by Berry, Narmour, Rink,

Schachter, Rothstein, Beach and, above all,

television commercials and pop songs are placed

alongside Bach chorales, Liszt's piano music,

Wagner's Trzstan Prelude, Chopin's ballades and

Debussy's Preludes, and these are in turn juxtaposed with Javanese Srepegan, the music of

Sudanese griots, Tongan dance and Garhwali

drumming. Not only does Monelle thus issue a

challenge to those who regard the boundaries between different musical traditions as secure; he

also encourages a reconfiguration of various

methods and methodologies. Distributional

analysis, generative analysis, intonation theory,

120

This content downloaded from 144.32.123.200 on Fri, 19 Jan 2024 23:34:50 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms