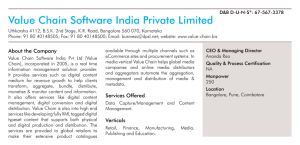

All Aboard the Job Train Government-funded training and recruitment in India’s apparel industry Orlanda Ruthven, 13 April 2016 ABSTRACT Every month, thousands of young women from poor eastern India are trained and brought to Bangalore to work in the city’s apparel factories. Written from within a government-funded skill and placement organization, the paper reveals the uncertain gain of contemporary employment in a global value chain: on the one hand, a framework of labour rights and benefits promises decent employment to youth who have known only underpaid and domestic drudgery. On the other, the force of capitalist employer and patriarchal recruiter combine to stymie the transformative potential of a regular job in the big city. 1. INTRODUCTION Since 2009, a dramatic shift in the policy of the Government of India has vastly increased the scope for young women and men to travel from interior rural areas to access organised employment in distant industrial centres. The new vocational training policy marked a shift from government-run training towards the promotion of a layer of private providers. It also marked the end of an era when informal and self-employment was viewed as the solution to poverty, and the start of the era where wage employment has taken centre stage. Several hundred private sector training entities have been brought into being as a result of support provided by government agencies such the National Skills Development Corporation (NSDC) and the Ministry of Rural Development. These entities are charged with recruiting poor students, training them and identifying jobs for them. Their mandate therefore straddles a role at source, from where the neophyte workers hail, and destination, the location of the job placement, in a process which facilitates migration. The majority of students pass through short-term, two month skill training courses in programmes which are billed as ‘job-linked’: the government, not unduly concerned with the quality of the training, views “placement in job” as the single indicator of achievementi. Thus, in order for the private provider to receive payment for training, not only must 75% of students be placed in jobs, but they must remain in employment for six months with the necessary payslips to prove it. How are we to interpret this policy? Its declared purpose is to ensure that India reaps dividends from its unique demography, i.e. from its exceptionally young, working-age population. But on the ground, the programmes appear to function less to skill the workforce than to subsidise its supply to industry (Ruthven 2013; Sarin 2012). Alternatively, could the government simply be offering a concession to poor youth as compensation for unbridled support to capitalist elites (Chatterjee 2008; Munster 2014)? Or is skills policy an undeclared component of security policy, a means to flush out the youth from the countryside, where they may otherwise become troublemakers (Ong 1991; Ruthven 2015)?ii Whatever the reason for the government’s policy, the significance of the torrent of rural youth newly flowing in to the formal job market should not be underestimated. Government funds ensure the new entities go deep into remote regions to recruit those who may otherwise have stayed at home. Once in 1|Page the job, formal employment offers a framework of rights and responsibilities, of non-discretionary procedures and a professional identity to young adults reared on the kinship and informal relations of the village milieu. While jobs in capitalist enterprises such as apparel firms are inevitably extractive, they are also potentially a force for development and can be a route through which youth, particularly young women, can grow more independent and build careers. Between 2013 and 2015, I had the opportunity to explore these issues while working with one skills and recruiting organisation, which I will call Learn and Earn Odisha (LEO). Part of my job was to create a range of post-placement support services in Bangalore in an effort to ensure a successful job experience for these young people. This paper draws on notes from field operations, offering an insider’s perspective of implementing government skills policy. The vista I had affords a granularity to the description and highlights the multiple perspectives on a single issue which emerge from different stakeholders even within the same organisation. The paper describes the attempts by a group of LEO staff (“the Bangalore team”) to realise the transformative potential of a formal sector job in Bangalore for young female migrants. It equally describes the difficulties encountered by this approach, as the various forces which regulate the lives of young women - families in the girls’ home village, the trainer-recruiter from Odisha and the employer from Bangalore – combine to prioritize protection and discipline over learning and freedom. The paper is organised in the following sections. The next section describes the two organisations involved in providing a programme of post-placement support in Bangalore, the skilling and recruitment agency (LEO), and the employer. Section 3 provides examples of recent operations in Bangalore that highlight the challenges of the programme and the responses of the various stakeholders, for example when young women drop out and return to the village, when they defy procedure to take leave in large groups, the incidence of boyfriends, the management of leisure time, and the response to critical illness. Section 4 discusses common themes that emerge from field observations: the tension between security and freedom of young women, the link between ideas of freedom and moral purity, group power versus individual rights, and the ambiguities of responsibility in government-funded skilling programmes. Section 5 summarizes and concludes the paper. 2. ORGANISATIONAL CONTEXT FOR LEO’S POST-PLACEMENT PROGRAMME The Training and Recruiting Agency Learn & Earn Odisha (LEO) is a social enterprise with residential training centres across Odisha and other eastern states. Offering skills training in multiple tradesiii, LEO’s single largest trade is industrial sewing machine operation (SMO), for which it trains 2000-3000 youth per year for supply to the southern apparel industry in Bangalore and Coimbatore. About 80% of these youth are women and about 60% from the traditionally disadvantaged communities of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes (adivasi)iv. LEO’s mobilisers recruit trainees through village networks and job fairs. They outline the opportunity at hand: free training, board and stay at the training campus for two months, and a guaranteed job after training. However, LEO mobilisers are sometimes prone to understate the commitment expected of trainees to depart for jobs in Bangalore, a 35-hour train ride from their homes where they should remain without leave for a minimum of six months. If it is discussed, parents are informed that their daughters will be protected, looked after and – of course - delivered back ‘intact’ (Maehre 27). 2|Page Once installed at the residential training centre in Odisha, students are required to give most time to technical training to become a line-ready industrial sewing operator (SMO). However, girls also receive ‘life skills’ training, including gender awareness and employability skills such as problem-solving, communications and self-management. The girls’ orientation extends into the hostel where they spend long evenings interacting with wardens and engaging in cultural programmes. The high number of adivasis among LEO’s SMO trainees is celebrated by the organisation as a marker of its depth of outreach. But this aspect of the trainee’s identity is also considered to be in need of remediation. Hostel wardens, for example, hold sessions during which “they teach the girls to control their behaviour” and learn to dress according to a modest mainstream code, e.g., no skirts that show any leg (Maehre, 22). Wardens interviewed by Maehre in 2014 interpreted their role thus: We make sure they follow [the] rules, are hygienic and dress in a proper way. We need restrictions for the trainees...they have limited independence. We cannot control them if they have full freedom (32, 33). Girls remark that during their two months in the LEO centre, their skin becomes paler as they remain shaded from the sun, day after day; they adapt to a fixed schedule and learn to “speak respectfully” (Maehre 30). Following the lengthy transit to Bangalore, LEO’s Bangalore team and the employer take over and provide the various post-placement functions. These consist initially of checking hostel accommodation, joining and settling the new arrivals into their new job and at a later stage, tracking their retention, collecting payslips, counselling and visiting those that are experiencing problems, delivery of further life skills training on a daily basis after work, and assisting in addressing grievances. From the outset, the hostel regime is distinct for the female majority and male minority. While male trainees have considerably more freedom, they often have to put up with a lower standard of accommodation. Employers at factory and hostel After two or three weeks in the employer’s training room, the trainees are slotted in to assembly line production, wherein garment parts are cumulatively sewn and assembled as they move across the shop floor. LEO’s ten or so employer partners in Bangalore produce shirts, denims and knitwear for all the global brands in units ranging from three hundred to a thousand workers. As firms struggle to fill the factory with local labour, they have increasingly dawn on migrants from outside Karnataka state. A requisite to drawing on this largely female workforce is to accommodate them, usually in apartment blocks run as self-catering hostels in the proximity of the factory. For an 8.5 hour working day, most of LEO’s trainees received a monthly gross wage of Rs.7076 in 2015, to which was added an attendance bonus of Rs.200. The compliance expected by foreign buyers means that the girls have little opportunity for earning overtimev. Their fuel and grocery costs tend to be well above Rs.1000 per month. The employer accommodation is charged at Rs.600 per month. Once these essential living expenses and statutory deductions have been paid for, the girls might end up with Rs.4,000 for a month where they had not fallen sick. Most girls’ financial situation is such that they must send as much money as possible back to their homes. 3|Page The transition from rural Orissa to urban-industrial Bangalore is dramatic for all girls. The factory environment, requiring “exact bodily posture and… tedious repetition of the same finger, eye and limb movements, often for hours on end at the assembly line”, is said to be a form of body discipline that is especially intolerable to neophyte factory women” (Ong 1991: 290). During the first month of stay, there is a lot of ‘churning’, when new arrivals refuse to stay, arguing that they are homesick, dislike the food, had not expected the wages to be so low, etc. The girls step into a closely surveyed regime between factory and hostel, where movement outside of either is restricted and where welfare officers and wardens, employed by the factory, play both disciplining and caring roles in the girls’ lives. Alongside this protective nurturing, the girls are exposed to a set of more adult relations with men on the shop floor. Supervisors push commands and instructions down the assembly line in order to extract work as efficiently as possible, and the girls must subscribe to targets that are impersonal and arbitrary. Young migrant workers are intermittently elevated to supervisor level, with the intent that the progression of the few will calm the frustration of the many. It is common for floor managers to proposition and even harass young women workers. Such employment relationships both foster and erode solidarity. The shop floor sets up workers in large numbers and within a shared, counter-relationship to management. The factory offers a new kind of friendship and cooperation with co-workers who hail from both similar and different backgrounds, including those who are native to the city. However, employment relationships can also frequently set one young female worker apart from the rest due to, for e.g., her speed and dexterity, her potential as a supervisor and her sexuality. The factory’s tight surveillance further impedes collective action. The sparse evidence from qualitative surveys, as well as the continued success of recruitment efforts, suggests that the basic opportunity offered by employers in Bangalore is attractive to Odisha’s youth because they come from poor backgrounds in regions where such a wage can achieve much. On the other hand, the scope for positive impacts from migrant wage work is diluted by early dropout and a return to the village (only 30% of LEO’s trainees last more than a year in Bangalore). But the reasons for early departure are not related to the basic opportunity per se, but rather, to pressures from home and the wider aspects of living in an industrial zone far removed from home (Pathak 2013; Ruthven, Patnaik et al. 2013; Maehre 2014)vi. These feature in the next section. 3. VIGNETTES FROM FIELD OPERATIONS Premature departure In December 2013, three young women, Monica, Mamta and Mehek joined one of India’s largest apparel exporters after training in Odisha. Despite high living costs and paltry wages, they stayed in Bangalore for several months. They said they liked being there, were making friends and enjoyed the work. One of the three, Mamta, was noted by staff to have supervisor potential. Five months later, only Monica remained. Hailing from the impoverished and drought-prone west of Odisha, Monica’s family had no land and few options for earning an income. Her father had encouraged her to go to the city, knowing that any income she contributed while staying in the village would be swallowed by his drinking habit. In contrast, Mamta and Mehek came from higher caste families on the 4|Page developed coast of the state. Both their brothers were in regular employment. In these families, the girls’ marriage prospects and status trumped any income they were able to bring home. From her third month, Mamta began requesting leave. The trigger for her change of mood was the new hostel warden, an Oriya woman promoted from the shop floor and enjoying her newfound power over her wards. There was also pressure from Mamta’s mother, calling every night, crying on the phone and worrying about her daughter’s safety and honour. Leaving before six months have passed is against LEO’s ‘rules’. This rule helps to persuade new recruits to remain in employment, despite the difficult period of adjustment and homesickness. It is also a way to of assuring value to employers who are desperate to retain skilled workers, and to collect the evidence on placement after training that LEO requires to report to the government. For these reasons, LEO refused Mamta’s requests for leave many times. However, in May 2014, her fifth month in the city, Mamta left with her best friend Mehek, at her mother’s insistence that she attend a family gathering. But on arrival, Mamta’s mother presented her with an ultimatum: get married now or you’ll be on the shelf. You’re dark-skinned and so you can’t be choosy. Mamta felt betrayed. She begged her parents that her marriage be delayed and in return, agreed to stay at home and complete grade 12, something that would add to her marriage prospects. Mehek, her friend, now faced a dilemma. She wanted to go back to Bangalore but was not confident without her friend. Her brother further discouraged her. While his sister’s earnings were a benefit to the cashstrapped family, he was beginning to sense the risks: could he be sure to protect her honour in Bangalore? Or even to keep control over what she earned? So Mehek stayed. In the end, she was safely married off before Mamta. On the rare times she is able to devote a few hours away from her domestic duties to meet her friend, the two girls weep about cutting short their stay in Bangalore. “Why were we in such a rush?” Mehek reminisces wistfully. Female jungle, male factory Every so often, an employer demands LEO’s intervention to ‘counsel’ a group of girls, or simply announces that they are dismissing them and requests that LEO inform their parents. The reasons behind such calls are usually the girls’ “disruptive” or “unruly” behaviour. But the incidents serve to highlight the cultural gap between the poor rural girls from eastern India and their male managers from the cosmopolitan south. One HR (Human Resources) manager called up in horror after witnessing a physical altercation between two girls from neighbouring communities as they grabbed each other’s hair and bit one another. “They are acting like savages! They should go back to their villages”, she insisted. In another, more prolonged incident in September 2014, two girls were reported to be ‘possessed’ by ghosts. We were asked by HR to facilitate their departure. Instead, we spent the day at the hostel. One of the two girls, Lalita, had been going into periodic trances during which she would murmur things about unknown people while remaining calm. Once she regained consciousness, she would explain that a god comes to rescue her and offers her comfort when she is stressed or frightened. Her friend, Gauri, on the other hand, had episodic fits of screaming and, the HR explained, this was disturbing hostel mates and “setting off” other girls. Gauri would wake from sleep in a fit-like state during which, she explained later, she was being haunted by a dangerous man called Ram Babu. 5|Page Concerned about the disruptive effects of one such episode, management sent a delegation of four men, who held Gauri down, put tulsi water on her, recited some mantras and put a coin on her head ‘to get the devil out of her’. They then advised a visit to the local mosquevii. In the end, management showed willing to avoid the knee-jerk response of dismissing the girls and sending them home: Lalita would not be sent home and for Gauri, a temporary leave period was negotiated during which she was able to recover in her village. Gauri’s hostel mates were matter-of-fact. They explained that wandering souls sometimes get into people’s bodies and the hostel cook added that this was most common during festival periods, when the gods are busy with pujas and demons are left freer to roam. The social regulation of leave-taking In March 2014, the Bangalore team was bombarded with requests from our training centres in Odisha to arrange leave for girls in various Bangalore factories. Rather than instructing their daughter to request leave from the company, families were approaching LEO’s training centres to demand the ‘release’ of their daughters. Where requests were not quickly granted, some families were even approaching government offices or politicians back home to step up the pressure. By the time such requests reached the Bangalore team, they were more like orders: speak with the respective HR department and “release so-and-so girl” since “her relatives are calling her home”. The first time the girls heared about such plans was when they were called to the HR office and told to take their ticket and collect their wages. One of our challenges in the Bangalore team was to convince our colleagues back in Odisha of the problems of this approach. One senior staff argued that he knew the correct procedures (i.e., the girl should apply for leave herself from the employer). But when parents’ requests come in, he said, “it is our duty” to respond. We’ve taken them away, he seemed to be saying, so it is our duty to get them back when their parents demand it. Surely, I replied, it was our duty to ensure they behave as adult employees. Had the girl in question even requested leave from her employer, I asked. The answer was ‘no’. Leave-taking for young migrants, it seemed, was regulated by the family and the village, with the recruiter acting as the family’s agent. Since joining their employment in Coimbatore in early 2014, a small group of girls had reportedly been complaining to their erstwhile trainers in north Odisha that they wanted to leave their employment. But when the Bangalore team visited the factory - a few hours’ drive away – it reported that the company appeared to be discharging its duties well and the majority of girls were content to continue working. But the rumours had gathered momentum and our staff in north Odisha now demanded that the complete group of girls be taken out of the company immediately. Some parents, we were told, were demanding ‘instant release’. Eventually, it was agreed that we would offer the trainees the choice, to follow procedure and leave the company, to stay on, or to join an alternative company in Bangalore. I thought about how LEO’s centres in Odisha continued to exert influence even in distant destinations, and how neither the girls’ families nor LEO’s own staff cared for building the relationship which the girls had with their employer. Such relationships require a respect for procedure, an understanding of the law, and a commitment to the moral authority of the employer. Yet it seemed some of LEO’s Odishabased staff might view this authority as an affront to their own. In spite of long days working as 6|Page employees in the factory, the girls respond to another set of values – the patriarchal force of family and the recruiter. Boyfriends and marriage In May 2014, I heard about a girl being targeted and punished by the hostel staff for having spent the day out with her boyfriend. Some recently arrived girls were adding their opinions, referring to those who “bring down the reputation of others, who can’t be trusted”. Pushpa was placed in work in 2013. Some months later, the warden and HR became aware that she had got married in Bangalore without informing anyone including her parents. Despite this not having influenced her work, she was asked to leave the hostel and her job, on the grounds that married women cannot be accommodated and that her behaviour set a bad example for the other girls. Rather than arranging her departure as requested by the company, the Bangalore team decided to get more information about the situation. If the couple had entered into marriage with clear minds and was happy with their decision, we would help Pushpa to stay in Bangalore. After meeting the new bride, my colleague sent a note to the rest of the Bangalore team: They have been dating for four years and have been very happy together. Regarding the girl, the husband has been very supportive through difficult times, never abuses her and they had no physical relationship prior to the marriage. Now, she wants to work for a year in Bangalore before setting up a home with him. He seems like a 'nice guy'. After a final unsuccessful attempt to persuade her employer to take Pushpa back, we found her a new job in another firm, where we informed HR that she was married and needed the freedom to meet with her husband who was living and working in Bangalore. However, the incident continued to bother me: why did the first company feel the need to dismiss her? What underlies such a response? Freedom at leisure In March 2014, we finally won the support of LEO’s largest employer to implement an eight hour open door policy in the girls’ hostels on Sundaysviii. Many HR staff were against the idea. Their reasons ranged from genuine safety concerns, to the need to confine the girls in order to secure their workforce. However, those in support of the change won the argument and recognised such confinement as a legal offence and a compliance riskix. We began with a trial in one hostel in which 130 girls lived. We offered all the girls the opportunity to go on an escorted tour of the city. The Bangalore team prepared itself well in the run-up to the date, providing girls with a map, a preparatory training session and informing them of emergency procedures. Five staff members took part in these activities. The employer also made preparations. The HR manager, cautious but tireless in her care of the girls, changed the hostel warden to one who would be strict in order to prevent the experiment getting out of 7|Page hand. A couple of days prior to the date, the employer produced a disclaimer in Hindi, announcing that the girls would only be allowed to go out after signing it. The disclaimer stated: “I am going out of the hostel today of my own free will. I take full responsibility for my behaviour while outside”. I did not think the disclaimer was a bad thing, as it would make the girls think about their responsibility. However, I was mistaken. The symbolic power of the written notice, requiring both a signature and thumb-print, was not lost on the employer. A rumour spread through the hostel: if the girls signed the declaration, the company would henceforth not be responsible for them. Caught in a dilemma between curiosity and fear, the girls called their parents and even their trainers back in Odisha. The advice was clear: do not sign anything and do not go out if you have to sign anything beforehand. LEO’s provincial staff, concerned to enforce a protective role of employer over their girls, was helping to derail the experiment. When the day of the outing finally arrived, only nine girls showed up instead of the 50 or so we had expected. A couple of coquettish girls kindly tried to explain to me their refusal to sign. “We don’t trust ourselves Ma’am, how do we know what we might do in this city? Better we stay here. Better we keep the company looking after us!” After an enjoyable day, we returned to the hostel in the evening to find the warden fuming at other girls who had left the hostel without signing the declaration. However, rather than staying out for the customary 1-2 hours, they had stayed away for the entire eight-hour period. Over the following weeks, we faced a bout of dropouts. I began losing the slim support I had won from my male staff members, with our operations officer in Bangalore commenting via email how girls were ‘abusing’ the freedom given to them. Mindful of LEO’s own strict hostel rules in its training centres, LEO’s VP stated, “Let us not expect the firm to do something we cannot implement on our own campus”. A death in Bangalore In October 2015, after three months in her job, Sarita Khora died of organ failure as a result of contracting dengue fever. Her death occurred around 10:00 am; we had only received our first alert about her being sick three hours earlier. Sarita’s roommates had attempted to alert us at 2:30 am, but my colleague, asleep, didn’t hear her call. The male security guard on duty had told the girls they needed to wait until morning to take an auto-rickshaw to the hospital. At 6:00 am, Sarita was taken by the same guard to a nearby clinic, which was ill-equipped to deal with serious illness. After giving her saline for two hours, the duty doctor advised the HR staff – which was now present at the hospital – to move her to a hospital with an ICU facility. However, her admission was refused and doctors referred her to the ESI hospital. En route between the two, Sarita died. What followed was a nightmare of paperwork to get the body cleared for post-mortem, acquire a death certificate and organise its release back to Odisha. The bureaucracy of death was not the only challenge. By the next morning, 230 Oriya hostel residents had gathered inside the hostel and declared they would not report to work, demanding that the company demonstrate how they would care for the son Sarita had left behind. While an ambulance with the body finally started the 35-hour journey by road to remote southern Odisha, the hostellers 8|Page expanded their demands to better drinking water, reduced confinement and attention to health problems on the part of staff. By now, Sarita’s body had reached her village. But her family refused to receive it until the company provided evidence that they would pay compensation. LEO’s provincial staff played a key role in this stance, quietly supporting the family and mediating the demand to the employer in Bangalore. After a tense few hours, during which negotiations continued between the family in Koraput and the employer in Bangalore, a cheque for Rs.3 lakhs was received by LEO staff and its photo sent by phone to our rural staff, who eventually persuaded the family to initiate Sarita’s last rites. I wrote to my colleagues to reflect on what had gone wrong. I advocated that the girls needed to be better equipped by us and by their employers to manage their health in a foreign context. My seniors were quick to react. The Bangalore team is doing too much women’s empowerment and not enough protection, they said. From now on, the focus would be on protection and rapid response in emergency. The idea of women living independently and managing their own lives was relegated back to being a distant pipe dream. With the death which stood before us, it seemed impossible to argue the case anymore. 4. DISCUSSION This section draws on literature from women in industrial work elsewhere to build a discussion around the vignettes described above, highlighting their central and shared themes into an analysis. Each vignette has shown how forces from “back home” – the girls’ families and LEO’s provincial staff continue to play influential roles in the lives of young women in new employment relationships. These forces combine with the capitalist employer to argue the case for protection, security and surveillance and stymie the nascent moves made by young women towards realising empowerment through their jobs. We divide the discussion into four topics: first, ideas of freedom with respect to young women; second, the ways in which ideas of purity and morality enter the transition from the village to Bangalore; third, the uneasy relationship between two types of power – vested in patriarchal-led groups and vested in rights for individuals; finally, the ambiguous nexus of responsibility created in such governmentsponsored training and placement programmes. Freedom and young women The experience of the girls in LEO’s Bangalore programme resonates with evidence from elsewhere. Ong (1991:287) writes about the claims that Chinese families have on their daughters’ labour in the context of export-led industrialisation during the late 1970s in Hong Kong and Taiwan. These claims serve to enforce workers’ compliance to the industrial employment regime, while also diminishing class-based solidarity in instances where family ties rule. As the months pass, the girls from LEO discover that they are essentially living in a silo or factory-cum-hostel, wherein almost all decision-making is shared between their families in the village and the company’s HR department, with the training and recruiting organisation viewing themselves as family representatives. 9|Page All three institutions (the family, the trainer-recruiter, the employer) share an interest in the girls’ safety: each stands to lose a great deal from a ‘mishap’ or a ‘scandal’ involving young female migrant workers; each stands to gain from a regime that manages to extract work and thus income on the one hand, while maintaining the integrity (corporeal, behavioural) of young female workers, on the other. After their arrival in Bangalore, women discover that behaviour which used to be viewed as acceptable and routine in the village, such as mobility in the neighbourhood or the playing out of possession by spirits, has now become transgressive and disruptive, defined as such by dominant groups, i.e., senior male managers. While certain behaviour, for example, engaging in pre-marital affairs, may be no more acceptable in the village, the scope for clandestine conduct is shrunk by new surveillance (Ong 1991: 293). Patriarchy from the home state is therefore acting in concert with capitalism at job destination, in a new combine, which risks putting women in the contradictory bind of being “whore” and “prisoner” at once (Ong 1987). Hartmann (1976) elaborates the relationship between patriarchy and capitalism: patriarchy adapts to capitalism to the extent of releasing young women into new male-led environments of exposure, while capitalism adjusts to patriarchy by responding differently to female and male workers and by adopting kinship idioms alongside more class-based forms of control. Thus, there is a promise of freedom that is directly related to the intrusion of capitalism into patriarchy. Ong and Hewamanne (2008) show how industrial employment, alongside the claims of family, offers young women new freedoms in the form of friendships, buying power and the postponement of marriage. In Bangalore, the leaders and the staff of export firms do not necessarily women’s freedom and empowerment but face challenges in its execution. During our Free Sunday experiment, for example, the problems and inconsistencies of confining working adults outside factory hours were clearer to the capitalist employer than to the patriarchal recruiter. LEO is used to running hostels for studentsx and saw nothing wrong with applying the same stringent standards to adult working women (for example, a gate time of 7.30 pm, no permission to leave the campus). In contrast, the HR chief of LEO’s largest employer partner saw the need to encourage migrant women to live outside, and was critical of his own staff’s decision to dismiss migrant couples who married in Bangalore. “Ideally we should offer mass marriage services” and encourage couples to settle, he remarked. While capitalist tactics of surveillance and targets are given a masculine flavour by the overwhelmingly male management on the shop floor, the masculine face of authority is not inevitable. Several exporters show themselves committed to promoting women operators as supervisors and managers. One example is the sadly unsung supervisor training programme for women operators, organised by three exporters in Bangalore in 2014 (Meta-Culture 2014). The results: all 34 women who attended the programme were subsequently offered supervisory roles. Capital, for all its extractive relations of production and the associated controls, is not the sole or even the main proponent of norms of confinement and transgression. Instead, such norms stem from capitalism’s adaptation to and accommodation of patriarchy, vested in the family and village milieu of the girls and their provincial trainer-recruiter. For the moment, in Bangalore, freedom and safety is experienced as a trade-off in a zero sum game; one is only available without the other. The idea that freedoms and rights can be guaranteed alongside safety remains a luxury of the rich. In the family, as in the factory, the one precludes the other. If a woman marries the man of her choice she is told she’s on her own; if she wants protection from the employer, she must stay in on Sundays. 10 | P a g e The impurity of transition In the context of young women migrants in Bangalore, ideas of freedom and empowerment become mixed up with those about impurity and shame. A girl who moves around the city, lives outside the hostels and negotiates her way in and out of jobs, is viewed as somewhat sullied. By allowing herself to realise her potential as a worker in a set of adult, employment relationships, she unwittingly leaves her integrity and honour open to threat. There is a proportion of young women, originally placed by LEO, who have since left their first jobs and have found their own way in the city, earning significantly more from jobs they have independently accessed. However, these women – rather than being role models for those less bold and brave – are frequently frowned upon and criticised by girls and their families for negatively affecting the reputation of “Oriya girls” in the city. While we have shown that even behaviours established in the village elicit new criticism once in the city, neophyte migrants also cultivate new behaviours, beginning with their stay on the patriarchal campus of the skilling and recruitment agency (see section 2). Some of these provide a route to a higher status and can be viewed as mimicking the behaviour of higher caste and urban women, but inherent in them is also new notions of freedom. Patrick Neveling (2006) describes how working women in Mauritius acquired a reputation for dating and using their wages as ‘lipstick money’, while at the same time subscribing to new social norms of monogamy and religiously moral behavior to aid their social status” (op cit, 9). Ong suggests a third aspect of impurity from new transgressions, which helps to explain the “savage” and unruly behaviour of some girls discussed in section 3. Ong (1987, 1988) interprets spirit possession as a response to the sharp break with village traditions made by young Malay women moving into work in factories. This geographical break forces a break with norms, leaving them vulnerable to spiritual attacks. Far from being viewed by women as a safer and purer environment, the factory is often viewed as dangerous. “The modern factory is an arena constituted by a sexual division of labour and constant male surveillance of nubile women in close, daily context… Young factory women themselves placed in a situation in which they unintentionally violate taboos defining social and bodily boundaries” (op cit, 34). The association of garment factory life with new impurities for young female migrants is also highlighted in studies conducted in Sri Lanka (Hewamanne 2008) and Bangladesh (AWAJ Foundation; AMRF Society et al. 2013). Thus, the idiom of purity is used in different contexts to refer to these girls’ origin (as uncivilised and low caste) and to what they become in the city (sullied, but also vulnerable on account of the village codes they have broken). Group power versus individual rights After finding jobs for trainees in Bangalore, LEO does not leave the girls to fend for themselves. It does not “dump and run”. Everyone in the organisation realises the need for various types of support to young women that are employed. However, the type of support activated is rooted in the patriarchal power of the group: representative power under the leadership of men from the home districts (such as trainers and centre heads), to whom the young women attribute moral authority. Even several months after arrival in Bangalore’s factories and hostels, it is at the instigation of male leaders from provincial Odisha that girls resist and protest, while these leaders use their ability to disrupt as a bargaining tool for better conditions. But, under this same leadership, girls also fall in line and accept, for example, being sent back home against their will or being locked up on Sundays. 11 | P a g e The legal framework has a small role here. Just as the patriarchal power exerted over the group can at times help to get laws enforced, so, too, can it help to push for conditions that have no legal basis. There is thus a gap in what the law promises (for example, employee rights in return for duties, limits to the employer’s power, social dialogue) and what patriarchal leaders tend to demand (for example, unbarred access to females by visiting male relatives, extension of employer protection to the hostel, compensation for a death outside work…). The individual basis of jurisdiction is also in contrast to the group basis of this patriarchal authority. While provincial leaders face limits to their influence because they are not always present or available in Bangalore, the alternative - the framework of individual rights and rules - remains remote. Hence, the group responds in an unruly manner in response to rumours, possession and death. In Ong’s study of young women workers in Malaysian electronics factories, managers tended to bundle such group responses as “mass hysteria”, seen as a response to the strain of the job (1988: 36). In LEO’s case, it is also linked to “primordial loyalties” (Chandavarkar 1994) of caste, community and region, aspects that these provincial leaders play up to. Young migrant women assert their identity neither as adults nor as employees but instead, as daughters, as trainees under the tutelage of leaders, as community members. In such a context, the realisation of their rights as individual employees still requires significant work. Who’s responsible? While ours is the story of neophyte migrants travelling for first-time formal employment, it is shaped deeply by government funds and the parties who mediate these funds: trainer recruiters. The fact of government funds increases the velocity at which new migrants flow into the sector, as also the depth of outreach at which young people are sourced. It is because they are financed by government that LEO’s young female migrants are who they are, i.e. from far-off poor states, vulnerable and ill-equipped to assimilate. The extent to which girls align with group patriarchal power (rather than branch out in search of other forms of power, such as associating with peers or exploring their rights) is also a function of their coming through government schemes, linked to their relatively short stay in the city. This is in contrast to both Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, where young unmarried women have trickled into apparel zones using their own resources and have stayed much longer, during which they appear to form subcultures of their own (Hewamanne, 2008; Ruthven, 2014). The combine of government and trainer-recruiter act to check the power of the employer but also create a new ambiguity in the employer’s moral authority. Southern apparel employers are among the safest and most legally compliant factories in the country. As capitalist enterprises, they will extract what they can from workers, while they remain disciplined by the law and less so by workers’ associational power. They are also integrated into global supply chains and build their business in an environment of submission to the ‘soft power’ (Ponte and Gibbon 2005) of contractual terms and quality, social and environmental standards, and in the context of competition with lower-waged and less regulated countries. The advent of the government schemes, however, creates some ambiguity in the responsibility of this principle employer. First, trained neophyte workers have arrived at the behest of government and trainer-recruiter, not through their own networks. While this means these parties share responsibility for the job outcomes, it also means that employers are dealing with a profile of worker (origin, education level, mother tongue etc) which they are not used to. Further, the motivation and orientation 12 | P a g e of these workers is influenced by those of the government and its agents, the trainer-recruiters. The government’s goal, after all, is to place in jobs (almost any job!) but only for a short period (the mandatory six months). This goal stands in clear contrast to that of the employer, seeking to build a well skilled and loyal workforce. Third, we have shown that inter-state female migrants cannot be lured to the factories without accommodation. Yet their attempts to provide accommodation (and related services such as water and transport) draw employers into new responsibilities which they had previous not taken and which has implications for city infrastructure and services. Predictably, the government at job destination (particularly municipality and local labour department) is unwilling and/ or unable to respond. Nonetheless, the failure of government to install an alternative framework of responsibility consequent to its skills programmes, means the onus will and must remain with the employer. There tends to be only a partial overlap between what employers should do, legally speaking, and what they must do in order to run their operations. Employers circumvent some legal requirements, while moving beyond others. In this way, several practices that are illegal have nonetheless become standard operational procedures. For example, running hostels without declaring them as such (the law governing hostels is considered too bureaucratic and punitive); confining young women to hostels because of a genuine concern for their safety, and hiring workers casually without registering them to the Provident Fund (PF), enabling them to wait out the mandatory period in Bangalore before withdrawing their savings. On the other hand, there are several ways in which employers do more than what is required by law, e.g., buttressing the ESI emergency system by organising transport and paying cash up-front; organising gas cylinders to enable migrant workers to cook; paying compensation to the family of workers who die outside of working hours. These efforts can be seen as compensating for the failure of government to follow through the effects of its own programmes and to provide a basic infrastructure like migrant support centres in consequence to its programmes. 5. CONCLUSION The paper has described the transition of young rural women from poor backgrounds travelling from the eastern state of Odisha to work in Bangalore’s apparel industry, through the sponsorship of central government schemes. Formal jobs in the apparel industry offer a framework of benefits and rights which make them attractive to migrants from India’s poor rural heartlands. And yet, the transformational possibilities are stymied by the combined force of capitalist extraction and patriarchal power emanating from the Bangalore-based employer, the trainer-recruiter and the girls’ own families back in the village. Drawing on experiences and events from field operations in Bangalore, the paper explored ideas of freedom, (im)purity and power as they play out for young women newly placed in jobs. The promise of employment, implying adulthood and individual rights and responsibilities, is mediated by patriarchal norms of protection and the confinement of young women and their rendition as “daughters” and “trainees”. Women discover that they can be assured security only by accepting limitations on their freedom. Ideas of transgression and purity play a key role here, wherein the regimes of factory and recruiter combine to critique behaviour from ‘back home’ and influence it towards “mainstream” ideas of dress, manners and seclusion. Young women respond with new behaviours mimicking the status markers and also the freedoms of urban educated professionals. In doing so, they implicitly reference the individualism (and associated rights and responsibilities) at the base of these behaviours. But the power of male-led groups from home tends to override that of individual rights in Bangalore and plays 13 | P a g e out even when young women live far from provincial patriarchal leaders. Individual rights may therefore have little influence for these workers until group patriarchal power has faded. The entry of patriarchal power into the capitalist context is facilitated by the particular circumstances and pressures exerted by government schemes. To reach placement targets, for example, trainerrecruiters like LEO must find jobs outside the source state, and this in turn creates the need for a framework of migrant support. The deeper dive to find adequate numbers of recruits from poorer backgrounds creates a profile of trainees which is more vulnerable and less equipped than that of more seasoned migrants. The key role of trainer, in recruiting for jobs and marketing the opportunity, disperses responsibility for safety and other outcomes, from the employer and from the girls themselves, towards these new intermediaries. The speed and scale of the government-led scheme map on to those of the industrial employer as surveillance is used to monitor and curb unacceptable behaviour. While government schemes have vastly increased the opportunity for young workers to access formal sector jobs, the same schemes thwart the scope for empowerment through these jobs. This is not only when they help to ease patriarchy’s entry into industry, but also when they obfuscate responsibilities and purpose among the expanded stakeholders involved. The transformative role of employment will require renewed focus on the moral authority of the employer and on installing the tools of self-efficacy and empowerment in the hands of young workers. REFERENCES AWAJ Foundation. 2013. Workers' Voice Report 2013: Insights into Life and Livelihood of Bangladesh's RMG Workers. Workers' Voice. Dhaka, Bangladesh, AWAJ Foundation. Chandavarkar, R. 1994. The Origins of Industrial Capitalism in India: Business Strategies and the Working Classes in Bombay 1900-1940. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chatterjee, P. 2008. "Democracy and Economic Transformation in India." Economic & Political Weekly 19: 53-62. Hartmann, H. 1976. "Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex." Signs 1(3):137-169. Hewamanne, S. 2008. "‘City of Whores’: nationalism, development and global garment workers in Sri Lanka." Social Text 95(26):2. Maehre, R. 2014. “A Study of Gram Tarang in Odisha: training and placement of young women”. Internship Report, Development Studies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Meta-Culture. 2014. Women's Supervisory Training Program. Bangalore, Meta-Culture. Munster, D. and C. Strumpell. 2014. "The anthropology of neoliberal India: an introduction." Contributions to Indian Sociology 48(1):1-16. Neveling, P. 2006. Spirits of capitalism and the de-alienation of workers: a historical perspective on the Mauritian garment industry. GSAA Online Working Papers. GSAA. Wittenberg, Germany, Martin Luther University. 14 | P a g e Ong, A. 1987. Spirits of Resistance & Capitalist Discipline: the Factory in Malaysia. Albany, State University of New York Press. Ong, A. (1988). "The production of possession: spirits & the multinational corporation in Malaysia." American Ethnologist 15:28-42. Ong, A. 1991. "The gender & labour politics of postmodernity." Annual Review of Anthropology 20:279309. Ong, A. 1991. "The gender and labor politics of postmodernity." Annual Review of Anthropology 20:279309. Pathak, P. 2013. “Experiences of placement in GTET: findings of the fieldwork in Jatni and Paralakhemundi campuses”. Gram Tarang Employability and Training Services, Bhubaneswar. Ponte, S. and P. Gibbon. 2005. "Quality standards, conventions and the governance of global value chains." Economy & Society 34 (1): 1-31. Ruthven, O. 2013. “Chapter 6: Skilling India”. The State of India's Livelihood Report 2013. Access Development Services. New Delhi, Sage. Ruthven, O. 2014. “Short note on the Bangladesh garment sector” for Faridabad Mazdoor Samachar newspaper, Faridabad, April 2014 issue Ruthven, O. 2015. Getting dividend from demography: skills policy and labour management in contemporary Indian industry.“Skills and Social Transformation in India”, workshop, 12-13 January 2015, Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford. Ruthven, O., et al. 2013. “First results from GTET tracer study, Gajapati District. Paralakhemundi, Odisha”, Centurion School of Rural Enterprise Management (CSREM), Centurion University of Technology and Management. Sarin, A. 2012. "Vocational education: a skillful use of public funds?" Vikalpa 37(3): 115-120. Steinisch, M., et al. 2013. "Work stress: its components and its association with self-reported health outcomes in a garment factory in Bangladesh - findings from a cross-sectional study." Health & Place 24:123-130. i At the time these schemes began, few standards were in place to assess training quality. Now, these standards are available (through the NSDC-promoted National Occupational Standards governed by the Sector Skills Councils), but the ministries that fund the running costs of training remain uninterested in whether a student passes a test or not. ii See for example http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/roshni-will-light-the-way-for-rural-youthjairam/article4792240.ece iii Other trades in which LEO offers skills training include machine operation for automotive manufacturing, call centre roles, hospitality, motor maintenance and electrician. iv The government identifies certain social groups as Scheduled i.e. qualifying for positive discrimination (or reservation) with respect to access to government jobs and institutions. While Scheduled Castes refer to the lowest castes of the Hindu caste hierarchy (also known as Dalits), Scheduled Tribes refer to groups who have been categorized as indigenous people or adivasis, living in remote regions prior to, and separately from, mainstream Indian society, particularly in India’s centre, east and north-east. 15 | P a g e v Curbing levels of overtime to India’s relatively restrictive Iegal norm of 50 hours per quarter (an average of 40 minutes per day) has been a key thrust of global buyer compliance. vi Also see Steinisch, M., et al. (2013). "Work stress: its components and its association with self-reported health outcomes in a garment factory in Bangladesh – findings from a cross-sectional study." Health & Place 24:123-130. vii The management’s response appeared to combine elements of Hinduism, Christianity and Islam in an effort to cover the religious bases for this tribal girl. viii It is standard practice to permit girls only two hours outside the hostel (enough time to do their shopping) on Sundays. ix That is, if hostels – generally hidden from the buyer auditors – were to be discovered, it is better if girls are not locked up. x Stringent regimes are routine in girls’ hostels in India, though confinement is illegal under Section 340 of the Indian Penal Code 1860. Recently, there has been a spate of newspaper articles in the national press highlighting and questioning the regime of girls’ hostels in colleges. See for example, http://indianexpress.com/article/cities/chandigarh/girls-staying-at-pu-hostels-lament-late-entry-fine-universitydefends-ageold-tradition/ 16 | P a g e