Decrypted by Service@yutou.org

Specially for Hùng Trung Thịnh

BUSINESS RESEARCH METHODS

This edition is dedicated to the memory of Professor Alan Bryman (1947-2017). H

­ undreds

of thousands of students across six continents have been fortunate enough to learn from

Alan’s publications. Few contemporary UK academics have had such a profound effect on

learning. At Oxford University Press we are incredibly proud of Alan’s significant achievements over the many years we worked with him. We thank him for everything he has done

for research methods as a discipline, and for his tireless dedication to the pursuit of shining

the light of understanding into the dark corners of students’ minds. It was a real pleasure

to work with him.

BUSINESS

RESEARCH METHODS

Fifth Edition

Emma Bell

Alan Bryman

Bill Harley

1

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Bell, Bryman and Harley 2019

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Second Edition 2007

Third Edition 2011

Fourth Edition 2015

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted

by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics

rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the

above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the

address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018949231

ISBN 978–0–19–254590–9

Printed in Italy by L.E.G.O. S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and

for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials

contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

BRIEF CONTENTS

PARTONE THE RESEARCH PROCESS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

The nature and process of business research

Business research strategies

Research designs

Planning a research project and developing research questions

Getting started: reviewing the literature

Ethics in business research

Writing up business research

PARTTWO QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

8 The nature of quantitative research

9 Sampling in quantitative research

10 Structured interviewing

11 Self-completion questionnaires

12 Asking questions

13 Quantitative research using naturally occurring data

14 Secondary analysis and official statistics

15 Quantitative data analysis

16 Using IBM SPSS statistics

PARTTHREE QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

17 The nature of qualitative research

18 Sampling in qualitative research

19 Ethnography and participant observation

20 Interviewing in qualitative research

21 Focus groups

22 Language in qualitative research

23 Documents as sources of data

24 Qualitative data analysis

25 Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis: using NVivo

PARTFOUR MIXED METHODS RESEARCH

26 Breaking down the quantitative/qualitative divide

27 Mixed methods research: combining quantitative and qualitative research

1

3

17

44

75

89

109

137

161

163

185

207

231

252

272

294

310

333

353

355

388

403

433

462

482

499

517

538

555

557

568

DETAILED CONTENTS

Abbreviations

xxvii

About the authors

xxviii

About the students and supervisors

xxx

Guided tour of textbook features

xxxii

Guided tour of the online resources

xxxiv

About the book

xxxvi

Acknowledgements

xlii

Editorial Advisory Panel

xliii

PARTONE THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

The nature and process of business research

1

3

Introduction

What is ‘business research’?

Why do business research?

Business research methods in context

Relevance to practice

The process of business research

Literature review

Concepts and theories

Research questions

Sampling

Data collection

Data analysis

Writing up

The messiness of business research

Key points

Questions for review

4

4

4

5

6

8

8

8

9

11

11

12

12

13

15

15

Business research strategies

17

Introduction: the nature of business research

Theory and research

What is theory?

Deductive and inductive logics of inquiry

Philosophical assumptions in business research

Ontological considerations

Objectivism

Constructionism

Epistemological considerations

A natural science epistemology: positivism

Interpretivism

Research paradigms

18

19

19

20

25

26

26

27

29

30

30

34

viii

Detailed contents

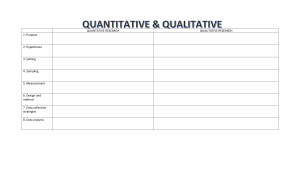

Developing a research strategy: quantitative or qualitative?

Other considerations

Values

Practicalities

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 3

Research designs

44

Introduction

Quality criteria in business research

Reliability

Replicability

Validity

Research designs

Experimental design

Cross-sectional design

Longitudinal design

Case study design

Comparative design

Level of analysis

Bringing research strategy and research design together

Key points

Questions for review

45

46

46

46

46

48

48

58

61

63

68

71

72

73

73

Chapter 4Planning a research project and developing

research questions

Chapter 5

35

37

37

39

42

42

75

Introduction

Getting to know what is expected of you by your university

Thinking about your research area

Using your supervisor

Managing time and resources

Developing suitable research questions

Criteria for evaluating research questions

Writing your research proposal

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

76

76

76

77

79

80

85

86

87

88

88

Getting started: reviewing the literature

89

Introduction

Reviewing the literature and engaging with what others

have written

Reading critically

Systematic review

Narrative review

Searching databases

Online databases

Keywords and defining search parameters

Making progress

Referencing

The role of the bibliography

90

91

92

92

97

98

98

100

102

103

104

Detailed contents

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Avoiding plagiarism

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

105

107

107

108

Ethics in business research

109

Introduction

The importance of research ethics

Ethical principles

Avoidance of harm

Informed consent

Privacy

Preventing deception

Other ethical and legal considerations

Data management

Copyright

Reciprocity and trust

Affiliation and conflicts of interest

Visual methods and research ethics

Ethical considerations in online research

The political context of business research

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

110

112

114

114

118

123

123

124

124

125

126

127

129

130

132

135

135

136

Writing up business research

137

Introduction

Writing academically

Writing up your research

Start early

Be persuasive

Get feedback

Avoid discriminatory language

Structure your writing

Writing up quantitative and qualitative research

An example of quantitative research

Introduction

Role congruity theory

Goals of the present study

Methods

Results

Discussion

Lessons

An example of qualitative research

Introduction

Loving to labour: identity in business schools

Methodology

Research findings

Discussion

Summary and conclusion

Lessons

138

138

140

141

141

142

142

143

147

147

148

148

148

149

149

149

150

152

152

153

153

153

153

154

155

ix

x

Detailed contents

Reflexivity and its implications for writing

Writing differently

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

PARTTWO QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

156

156

157

158

159

161

The nature of quantitative research

163

Introduction

The main steps in quantitative research

Concepts and their measurement

What is a concept?

Why measure?

Indicators

Dimensions of concepts

Reliability of measures

Stability

Internal reliability

Inter-rater reliability

Validity of measures

Face validity

Concurrent validity

Predictive validity

Convergent validity

Discriminant validity

The connection between reliability and validity

The main preoccupations of quantitative researchers

Measurement

Causality

Generalization

Replication

The critique of quantitative research

Criticisms of quantitative research

Is it always like this?

Reverse operationism

Reliability and validity testing

Sampling

Key points

Questions for review

164

164

167

167

168

168

169

172

172

173

173

174

174

174

174

175

175

175

175

176

177

177

178

180

181

182

182

182

183

183

184

Sampling in quantitative research

185

Introduction

Introduction to sampling

Sampling error

Types of probability sample

Simple random sample

Systematic sample

Stratified random sampling

186

187

189

191

191

191

192

Detailed contents

Multi-stage cluster sampling

The qualities of a probability sample

Sample size

Absolute and relative sample size

Time and cost

Non-response

Heterogeneity of the population

Types of non-probability sampling

Convenience sampling

Quota sampling

Limits to generalization

Error in survey research

Sampling issues for online surveys

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 10 Structured interviewing

Introduction

The structured interview

Reducing error due to interviewer variability

Accuracy and ease of data processing

Other types of interview

Interview contexts

More than one interviewee

More than one interviewer

In person or by telephone?

Computer-assisted interviewing

Conducting interviews

Know the schedule

Introducing the research

Rapport

Asking questions

Recording answers

Clear instructions

Question order

Probing

Prompting

Leaving the interview

Training and supervision

Other approaches to structured interviewing

The critical incident method

Projective methods, pictorial methods, and photo-elicitation

The verbal protocol approach

Problems with structured interviewing

Characteristics of interviewers

Response sets

The problem of meaning

Key points

Questions for review

192

193

195

195

196

196

197

197

197

198

201

202

202

204

205

207

208

208

208

210

210

212

212

212

212

214

215

215

215

216

216

217

217

217

219

220

221

221

222

222

223

226

226

226

227

228

229

229

xi

xii

Detailed contents

Chapter 11 Self-completion questionnaires

Introduction

Different kinds of self-completion questionnaires

Evaluating the self-completion questionnaire in relation to

the structured interview

Advantages of the self-completion questionnaire over the

structured interview

Disadvantages of the self-completion questionnaire in

comparison to the structured interview

Steps to improve response rates to postal and online

questionnaires

Designing the self-completion questionnaire

Do not cramp the presentation

Clear presentation

Vertical or horizontal closed answers?

Identifying response sets in a Likert scale

Clear instructions about how to respond

Keep question and answers together

Email and online surveys

Email surveys

Web-based surveys

Comparing modes of survey administration

Diaries as a form of self-completion questionnaire

Advantages and disadvantages of the diary as a method

of data collection

Experience and event sampling

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 12 Asking questions

Introduction

Open or closed questions?

Open questions

Closed questions

Types of question

Rules for designing questions

General rules of thumb

Specific rules when designing questions

Vignette questions

Piloting and pre-testing questions

Using existing questions

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 13 Quantitative research using naturally occurring data

Introduction

Structured observation

The observation schedule

Strategies for observing behaviour

231

232

232

232

233

234

235

237

237

237

238

239

239

240

240

240

241

242

245

247

248

251

251

252

253

253

253

254

256

258

258

258

263

265

265

268

269

270

272

273

273

275

275

Detailed contents

Sampling for structured observation

Sampling people

Sampling in terms of time

Further sampling considerations

Issues of reliability and validity

Reliability

Validity

Criticisms of structured observation

On the other hand …

Content analysis

What are the research questions?

Selecting a sample for content analysis

Sampling media

Sampling dates

What is to be counted?

Significant actors

Words

Subjects and themes

Dispositions

Images

Coding in content analysis

Coding schedule

Coding manual

Potential pitfalls in devising coding schemes

Advantages of content analysis

Disadvantages of content analysis

Key points

Questions for review

276

276

276

276

278

278

278

279

280

280

281

282

282

282

283

283

283

284

284

284

285

286

286

288

290

290

291

292

Chapter 14 Secondary analysis and official statistics

294

Introduction

Other researchers’ data

Advantages of secondary analysis

Limitations of secondary analysis

Accessing data archives

Archival proxies and meta-analysis

Official statistics

Reliability and validity

Official statistics as a form of unobtrusive measure

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 15 Quantitative data analysis

Introduction

A small research project

Missing data

Types of variable

Univariate analysis

Frequency tables

Diagrams

295

295

296

301

302

304

306

308

308

308

309

310

311

311

313

316

318

318

319

xiii

xiv

Detailed contents

Measures of central tendency

Measures of dispersion

Bivariate analysis

Relationships, not causality

Contingency tables

Pearson’s r

Spearman’s rho

Phi and Cramér’s V

Comparing means and eta

Multivariate analysis

Could the relationship be spurious?

Could there be an intervening variable?

Could a third variable moderate the relationship?

Statistical significance

The chi-square test

Correlation and statistical significance

Comparing means and statistical significance

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 16 Using IBM SPSS statistics

Introduction

Getting started in SPSS

Beginning SPSS

Entering data in the Data Viewer

Defining variables: variable names, missing values,

variable labels, and value labels

Recoding variables

Computing a new variable

Data analysis with SPSS

Generating a frequency table

Generating a bar chart

Generating a pie chart

Generating a histogram

Generating the arithmetic mean, median,

standard deviation, range, and boxplots

Generating a contingency table, chi-square,

and Cramér’s V

Generating Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rho

Generating scatter diagrams

Comparing means and eta

Generating a contingency table with

three variables

Further operations in SPSS

Saving your data

Retrieving your data

Printing output

Key points

Questions for review

320

320

321

321

322

323

324

325

325

326

326

326

326

327

328

330

330

331

331

333

334

335

335

335

337

338

340

341

341

342

342

343

343

343

344

345

346

346

347

347

351

351

351

352

Detailed contents

PARTTHREE QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Chapter 17 The nature of qualitative research

Introduction

The main steps in qualitative research

Theory and research

Concepts in qualitative research

Reliability and validity in qualitative research

Adapting reliability and validity for qualitative research

Alternative criteria for evaluating qualitative research

Overview of the issue of criteria

The main preoccupations of qualitative researchers

Seeing through the eyes of people being studied

Description and emphasis on context

Emphasis on process

Flexibility and limited structure

Concepts and theory grounded in data

Not just words

The critique of qualitative research

Qualitative research is too subjective

Qualitative research is difficult to replicate

Problems of generalization

Lack of transparency

Is it always like this?

Contrasts between quantitative and qualitative research

Similarities between quantitative and qualitative research

Researcher–participant relationships

Action research

Feminism and qualitative research

Postcolonial and indigenous research

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 18 Sampling in qualitative research

Introduction

Levels of sampling

Purposive sampling

Theoretical sampling

Generic purposive sampling

Snowball sampling

Sample size

Not just people

Using more than one sampling approach

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 19 Ethnography and participant observation

Introduction

Organizational ethnography

353

355

356

357

360

361

362

362

363

365

366

366

367

368

369

369

369

374

374

374

374

375

376

376

378

379

379

381

384

385

386

388

389

390

391

391

394

395

397

399

400

401

401

403

404

405

xv

xvi

Detailed contents

Access

Overt versus covert?

Ongoing access

Key informants

Roles for ethnographers

Active or passive?

Shadowing

Field notes

Types of field notes

Bringing ethnographic fieldwork to an end

Feminist ethnography

Global and multi-site ethnography

Virtual ethnography

Visual ethnography

Writing ethnography

Realist tales

Other approaches

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 20 Interviewing in qualitative research

Introduction

Differences between the structured interview and the

qualitative interview

Asking questions in the qualitative interview

Preparing an interview guide

Kinds of questions

Using an interview guide: an example

Recording and transcription

Non-face-to-face interviews

Telephone interviewing

Online interviews

Interviews using Skype

Life history and oral history interviews

Feminist interviewing

Merits and limitations of qualitative interviewing

Advantages of qualitative interviews

Disadvantages of qualitative interviews

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 21 Focus groups

Introduction

Uses of focus groups

Conducting focus groups

Recording and transcription

How many groups?

Size of groups

Level of moderator involvement

Selecting participants

407

410

411

413

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

425

426

426

428

431

431

433

434

435

436

439

441

443

445

450

451

451

452

454

455

457

457

458

459

460

460

462

463

464

465

465

466

468

468

470

Detailed contents

Asking questions

Beginning and finishing

Group interaction in focus group sessions

Online focus groups

The focus group as an emancipatory method

Limitations of focus groups

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 22 Language in qualitative research

Introduction

Discourse analysis

Main features of discourse analysis

Interpretive repertoires and detailed procedures

Critical discourse analysis

Narrative analysis

Rhetorical analysis

Conversation analysis

Overview

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 23 Documents as sources of data

Introduction

Personal documents

Public documents

Organizational documents

Media outputs

Visual documents

Documents as ‘texts’

Interpreting documents

Qualitative content analysis

Semiotics

Historical analysis

Checklist

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 24 Qualitative data analysis

Introduction

Thematic analysis

Grounded theory

Tools of grounded theory

Outcomes of grounded theory

Memos

Criticisms of grounded theory

More on coding

Steps and considerations in coding

Turning data into fragments

The critique of coding

470

471

472

473

476

478

479

480

480

482

483

483

484

486

488

489

491

493

496

497

497

499

500

500

503

504

506

507

510

511

511

512

512

514

515

515

517

518

519

521

521

522

524

525

530

531

531

533

xvii

xviii

Detailed contents

Secondary analysis of qualitative data

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 25 Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis: using NVivo

Introduction

Is CAQDAS like quantitative data analysis software?

No industry leader

Limited acceptance of CAQDAS

Learning NVivo

Coding

Searching data

Memos

Saving an NVivo project

Opening an existing NVivo project

Final thoughts

Key points

Questions for review

PARTFOUR MIXED METHODS RESEARCH

Chapter 26 Breaking down the quantitative/qualitative divide

Introduction

The natural science model and qualitative research

Quantitative research and interpretivism

Quantitative research and constructionism

Epistemological and ontological considerations

Problems with the quantitative/qualitative contrast

Behaviour versus meaning

Theory tested in research versus theory emergent from data

Numbers versus words

Artificial versus natural

Reciprocal analysis

Qualitative analysis of quantitative data

Quantitative analysis of qualitative data

Quantification in qualitative research

Thematic analysis

Quasi-quantification in qualitative research

Combating anecdotalism through limited quantification

Key points

Questions for review

Chapter 27Mixed methods research: combining quantitative

and qualitative research

Introduction

The arguments against mixed methods research

The embedded methods argument

The paradigm argument

Two versions of the debate about quantitative and

qualitative research

534

537

537

538

539

539

539

539

541

542

550

552

553

553

553

553

553

555

557

558

558

560

561

561

562

562

562

562

563

564

564

565

565

565

566

566

566

567

568

569

569

569

570

570

Detailed contents

The rise of mixed methods research

Classifying mixed methods research in terms of priority

and sequence

Different types of mixed methods design

Approaches to mixed methods research

The logic of triangulation

Qualitative research facilitates quantitative research

Quantitative research facilitates qualitative research

Filling in the gaps

Static and processual features

Research issues and participants’ perspectives

The problem of generality

Interpreting the relationship between variables

Studying different aspects of a phenomenon

Solving a puzzle

Quality issues in mixed methods research

Key points

Questions for review

571

571

573

574

574

576

576

576

578

579

579

579

581

583

585

586

586

Glossary

589

References

599

Name index

623

Subject index

629

xix

LEARNING FEATURES

1.1

Key concept What is evidence-based management?

7

1.2

Key concept What are research questions?

9

1.3

Research in focus A research question about gender bias

in attitudes towards leaders

10

1.4

Thinking deeply What is big data?

13

2.1

Key concept What is empiricism?

20

2.2

Research in focus A deductive study

22

2.3

Research in focus An inductive study

23

2.4

Key concept What is abductive reasoning?

24

2.5

Key concept What is the philosophy of social science?

25

2.6

Key concept What is objectivism?

26

2.7

Key concept What is constructionism?

27

2.8

Key concept What is postmodernism?

28

2.9

Research in focus Constructionism in action

28

2.10

Key concept What is positivism?

30

2.11

Key concept What is empirical realism?

31

2.12

Key concept What is interpretivism?

31

2.13

Research in focus Interpretivism in practice

33

2.14

Key concept What is a paradigm?

34

2.15

Research in focus Mixed methods research—an example

36

2.16

Thinking deeply Factors that influence methods choice in

organizational research

38

2.17

Research in focus Influence of an author’s biography on research values

39

3.1

Key concept What is a research design?

45

3.2

Key concept What is a research method?

45

3.3

Key concept What is a variable?

47

3.4

Research in focus An example of a field experiment to

investigate obesity discrimination in job applicant selection

49

3.5

Research in focus Establishing the direction of causality

53

3.6

Research in focus A laboratory experiment on voting on CEO pay

54

3.7

Research in focus The Hawthorne effect

55

3.8

Research in focus A quasi-experiment

56

3.9

Key concept What is evaluation research?

57

3.10

Research in focus An evaluation study of role redesign

57

3.11

Key concept What is a cross-sectional research design?

59

Learning features

3.12

Key concept What is survey research?

59

3.13

Research in focus An example of survey research: the Study of

Australian Leadership (SAL)

60

3.14

Research in focus A representative sample?

62

3.15

Thinking deeply The case study in business research

64

3.16

Research in focus A longitudinal case study of ICI

65

3.17

Research in focus A longitudinal panel study of older workers’ pay

68

3.18

Key concept What is cross-cultural and international research?

69

3.19

Research in focus A comparative analysis panel study of female employment

71

4.1

Thinking deeply Marx’s sources of research questions

81

4.2

Research in focus Developing research questions

84

5.1

Key concept What is an academic journal?

90

5.2

Thinking deeply Composing a literature review in qualitative research articles

93

5.3

Key concept What is a systematic review?

94

5.4

Research in focus A narrative review of narrative research

6.1

Key concept Stances on ethics

111

6.2

Research in focus A covert study of unofficial rewards

112

6.3

Research in focus Two infamous studies of obedience to authority

112

6.4

Thinking deeply Harm to non-participants?

114

6.5

Thinking deeply The assumption of anonymity

117

6.6

Research in focus An example of an ethical dilemma in fieldwork

124

6.7

Research in focus Ethical issues in a study involving friends as respondents

127

6.8

Thinking deeply A funding controversy in a university business school

128

6.9

Research in focus Invasion of privacy in visual research

129

6.10

Research in focus Chatroom users’ responses to being studied

131

7.1

Key concept What is rhetoric?

138

7.2

Thinking deeply How to write academically

139

7.3

Thinking deeply An empiricist repertoire?

151

7.4

Key concept What is a rhetorical strategy in quantitative research?

151

7.5

Thinking deeply Using verbatim quotations from interviews

154

8.1

Research in focus Selecting research sites and sampling respondents:

the Quality of Work and Life in Changing Europe project

166

8.2

Key concept What is an indicator?

169

8.3

Research in focus A multiple-indicator measure of a concept

170

8.4

Research in focus Specifying dimensions of a concept: the case of

job characteristics

171

8.5

Key concept What is reliability?

172

8.6

Key concept What is Cronbach’s alpha?

173

8.7

Key concept What is validity?

174

8.8

Research in focus Assessing the internal reliability and the concurrent

and predictive validity of a measure of organizational climate

176

97

xxi

xxii

Learning features

8.9

Research in focus Testing validity through replication: the case of burnout

179

8.10

Key concept What is factor analysis?

183

9.1

Key concept Basic terms and concepts in sampling

188

9.2

Research in focus A cluster sample survey of Australian workplaces

and employees

193

9.3

Key concept What is a response rate?

197

9.4

Research in focus Convenience sampling in a study of discrimination in hiring

199

10.1

Key concept What is a structured interview?

209

10.2

Key concept Major types of interview

211

10.3

Research in focus A telephone survey of dignity at work

213

10.4

Research in focus A question sequence

219

10.5

Research in focus An example of the critical incident method

223

10.6

Research in focus Using projective methods in consumer research

224

10.7

Research in focus Using pictorial exercises in a study of business

school identity

225

10.8

Key concept What is photo-elicitation?

225

10.9

Research in focus Using photo-elicitation to study tourist behaviour

225

10.10 Research in focus A study using the verbal protocol method

226

10.11 Research in focus A study of the effects of social desirability bias

228

Research in focus Combining the use of structured interviews with

­self-completion questionnaires

233

11.2

Research in focus Administering a survey in China

235

11.3

Key concept What is a research diary?

246

11.4

Research in focus A diary study of managers and their jobs

247

11.5

Research in focus A diary study of text messaging

248

11.6

Research in focus A diary study of emotional labour in a call centre

249

11.7

Research in focus Using diaries to study a sensitive topic: work-related gossip

249

12.1

Research in focus Coding a very open question

254

12.2

Research in focus Using vignette questions in a tracking study

of ethical behaviour

264

Research in focus Using scales developed by other researchers in a study

of high performance work systems

266

13.1

Key concept What is structured observation?

274

13.2

Research in focus Mintzberg’s categories of basic activities involved

in managerial work

274

13.3

Research in focus Structured observation with a sample of one

277

13.4

Key concept What is Cohen’s kappa?

278

13.5

Key concept What is content analysis?

281

13.6

Research in focus A content analysis of courage and managerial

decision-making

283

13.7

Research in focus A computer-aided content analysis of microlending

to entrepreneurs

284

11.1

12.3

Learning features

13.8

Research in focus Issues of inter-coder reliability in a study of text messaging

289

13.9

Research in focus A content analysis of Swedish job advertisements

1960–2010

291

14.1

Key concept What is secondary analysis?

295

14.2

Research in focus Exploring corporate reputation in three

Scandinavian countries

296

Research in focus Combining primary and secondary data in a single study

of the implications of marriage structure for men’s attitudes to women in

the workplace

297

Research in focus Cross-national comparison of work orientations:

an example of a secondary dataset

299

Research in focus Workplace gender diversity and union density:

an example of secondary analysis using the WERS data

299

Research in focus Age and work-related health: methodological issues

involved in secondary analysis using the Labour Force Survey

300

Research in focus The use of archival proxies in the field of

strategic management

304

14.8

Key concept What is meta-analysis?

305

14.9

Research in focus A meta-analysis of research on corporate social

responsibility and performance in East Asia

305

14.3

14.4

14.5

14.6

14.7

14.10 Key concept What is the ecological fallacy?

306

14.11 Key concept What are unobtrusive measures?

307

15.1

Key concept What is a test of statistical significance?

328

15.2

Key concept What is the level of statistical significance?

329

17.1

Thinking deeply Research questions in qualitative research

359

17.2

Research in focus The emergence of a concept in qualitative research:

‘emotional labour’

361

17.3

Key concept What is respondent validation?

363

17.4

Key concept What is triangulation?

364

17.5

Research in focus Seeing practice-based learning from the perspective

of train dispatchers

367

17.6

Research in focus Studying process and change in the Carlsberg group

368

17.7

Research in focus An example of dialogical visual research

370

17.8

Research in focus An example of practice visual research

372

17.9

Thinking deeply A quantitative review of qualitative research

in management and business

375

17.10 Research in focus Using visual methods in participatory

action research study of a Ghanaian cocoa value chain

380

17.11 Thinking deeply Feminist research in business

383

17.12 Research in focus A feminist analysis of embodied identity at work

384

17.13 Research in focus Indigenous ways of understanding leadership

385

18.1

Key concept What is purposive sampling?

389

18.2

Key concept Some purposive sampling approaches

390

xxiii

xxiv

Learning features

18.3

Key concept What is theoretical sampling?

392

18.4

Key concept What is theoretical saturation?

394

18.5

Research in focus An example of theoretical sampling

394

18.6

Research in focus A snowball sample

396

18.7

Thinking deeply Saturation and sample size

399

19.1

Key concept Differences and similarities between ethnography

and participant observation

404

Research in focus An example of an organizational ethnography

lasting nine years

405

19.3

Research in focus Finding a working role in the organization

408

19.4

Research in focus A complete participant?

410

19.5

Research in focus An example of the difficulties of covert observation:

the case of field notes in the lavatory

411

19.6

Key concept What is ‘going native’?

414

19.7

Research in focus Using field note extracts in data analysis and writing

417

19.8

Research in focus An ethnography of work from a woman’s perspective

419

19.9

Research in focus ‘Not one of the guys’: ethnography

in a male-dominated setting

420

19.2

19.10 Research in focus A multi-site ethnography of diversity management

421

19.11 Research in focus Netnography

422

19.12 Research in focus Using blogs in a study of word-of-mouth marketing

423

19.13 Research in focus Ethical issues in a virtual ethnography

of change in the NHS

424

19.14 Key concept What is visual ethnography?

425

19.15 Key concept Three forms of ethnographic writing

426

19.16 Research in focus Realism in organizational ethnography

427

19.17 Key concept What is the linguistic turn?

429

19.18 Key concept What is auto-ethnography?

429

19.19 Research in focus Identity and ethnographic writing

430

20.1

Research in focus An example of unstructured interviewing

437

20.2

Research in focus Flexibility in semi-structured interviewing

437

20.3

Research in focus Using photographs as prompts in a study

of consumer behaviour

439

20.4

Research in focus Part of the transcript of a semi-structured interview

444

20.5

Research in focus Getting it recorded and transcribed: an illustration

of two problems

446

Research in focus Constructionism in a life history study

of occupational careers

455

21.1

Key concept What is the focus group method?

463

21.2

Research in focus Using focus groups to study

trade union representation of disabled employees

467

Research in focus Moderator involvement in a focus group discussion

469

20.6

21.3

Learning features

21.4

Research in focus Using focus groups in a study of female entrepreneurs

472

21.5

Research in focus An asynchronous focus group study

473

21.6

Research in focus An example of the focus group

as an emancipatory method

477

21.7

Research in focus Group conformity and the focus group method

479

22.1

Key concept What is discourse analysis?

484

22.2

Research in focus The application of mind and body discourses

to older workers

484

Research in focus Interpretative repertoires in the identification

of role models by MBA students

485

22.4

Key concept What are organizational narratives?

490

22.5

Research in focus An example of narratives in a hospital

491

22.6

Research in focus The rhetorical construction of charismatic

leadership

492

22.7

Key concept What is conversation analysis?

493

22.8

Research in focus A study of hospital teamwork using

ethnomethodology and conversation analysis

495

Research in focus A study of online diaries written

by white-collar workers

501

Research in focus Using autobiographical sources to study

high-profile women leaders

503

Research in focus Two studies using public documents to analyse

a policing disaster

504

Research in focus An analysis of public documents

in leadership research

506

23.5

Thinking deeply Three ways of using photographs as documents

508

23.6

Research in focus Analysing photographs in a study

of brand identity in a UK bank

508

23.7

Research in focus A semiotic analysis of a funeral business

513

23.8

Thinking deeply Three arguments for historical analysis

in studying organizations

513

Research in focus A genealogical historical analysis

of management thought

514

24.1

Key concept What is a theme?

519

24.2

Key concept What is grounded theory?

521

24.3

Key concept Coding in grounded theory

523

24.4

Research in focus Categories in grounded theory

523

24.5

Research in focus A grounded theory approach in a study

of a corporate spin-off

526

24.6

Key concept What is first- and second-order analysis?

528

24.7

Research in focus A memo

528

24.8

Key concept What is meta-ethnography?

535

24.9

Research in focus A meta-ethnography of research on the experiences

of people with common mental disorders when they return to work

536

22.3

23.1

23.2

23.3

23.4

23.9

xxv

xxvi

Learning features

25.1

Key concept What is a node?

26.1

Research in focus A critical realist study of innovation in Australia

560

26.2

Research in focus The construction of meaning from numerical data

564

27.1

Key concept What is mixed method research?

569

27.2

Research in focus Using qualitative data to inform

quantitative measurement

577

Research in focus Using quantitative research to facilitate

qualitative research

577

Research in focus Using quantitative data about time use to fill

in the gaps in a qualitative study

578

27.5

Research in focus A mixed methods case study

580

27.6

Research in focus Expanding on quantitative findings with

qualitative research in a study of leadership

582

Research in focus Combining netnography and an online survey

in a study of a virtual community of consumers

583

Research in focus Using mixed methods research to solve a puzzle:

the case of displayed emotions in convenience stores

584

27.3

27.4

27.7

27.8

543

ABBREVIATIONS

AoIR

AOM

ASHE

BHPS

BRES

BSA

CAPI

CAQDAS

CATI

CEO

CMD

CSR

CV

CWP

ECA

ESRC

EWCS

FTSE

GDPR

GMID

GSS

HISS

HP

HR

HRM

ICI

ISP

ISSP

Association of Internet Researchers

Academy of Management

Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

British Household Panel Study

Business Register and Employment Survey

British Social Attitudes; British Sociological

Association

computer-assisted personal interviewing

computer-assisted qualitative data analysis

software

computer-assisted telephone interviewing

chief executive officer

common mental disorder

corporate social responsibility

curriculum vitae

Changing Workforce Programme

ethnographic content analysis

Economic and Social Research Council

European Working Conditions Survey

Financial Times Stock Exchange (London)

General Data Protection Regulations

(European Union)

General Market Information Database

General Social Survey (USA)

hospital information support system

Hewlett Packard

human resources

human resource management

Imperial Chemical Industries

internet service provider

International Social Survey Programme

IT

JDS

LFS

LGI

LPC

MBA

MORI

MPS

MRS

NASA

NHS

NOS

OCS

OD

OECD

ONS

R&D

RTW

SIC

SME

SSCI

SRA

TDM

TQM

UKDA

VDL

WERS

WOMM

information technology

Job Diagnostic Survey

Labour Force Survey

Looking Glass Inc.

least-preferred co-worker

Master of Business Administration

Market & Opinion Research International

Motivating Potential Score

Market Research Society

National Air and Space Administration (USA)

National Health Service

National Organizations Survey (USA)

Organizational Culture Scale

organizational development

Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development

Office for National Statistics

research and development

return to work

Standard Industrial Classification

small or medium-sized enterprise

Social Sciences Citation Index

Social Research Association

total design method

total quality management

UK Data Archive

vertical dyadic linkage

Workplace Employment Relations Survey

(previously Workplace Employee Relations

Survey)

word-of-mouth marketing

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Emma Bell is Professor of Organisation Studies at the

Open University, UK. She completed her PhD at Manchester Metropolitan University in 2000 based on an

ethnographic study of payment systems and time in

the chemical industry. Prior to this, Emma worked as a

graduate trainee in the UK National Health Service. Her

research is informed by curiosity about the ways in which

people in organizations collectively construct meaning in

the context of work and organizations. Recently, she has

been involved in projects related to visual organizational

analysis, understanding craft work, and power and politics in the production of management knowledge.

Emma’s research has been published in British Journal of Management, Academy of Management Learning

and Education, and Organization. She has an enduring

interest in methods and methodological issues and has

published articles, chapters, and books related to this

including, A Very Short, Fairly Interesting and Reasonably

Cheap Book about Management Research (Sage, 2013),

co-authored with Richard Thorpe, and Sage Major Works

in Qualitative Research in Business and Management

(2015), co-edited with Hugh Willmott. Emma served as

a co-chair of the Critical Management Studies Division

of the Academy of Management; at the time of writing

she is joint vice-chair of research and publications for the

British Academy of Management and joint editor-in-chief

of Management Learning.

Alan Bryman was Professor of Organizational and Social

Research at the University of Leicester from 2005 to

2017. Prior to this he was Professor of Social Research at

Loughborough University for 31 years.

His main research interests were in leadership, especially in higher education, research methods (particularly mixed methods research), and the ‘Disneyization’

and ‘McDonaldization’ of modern society. In 2003–4 he

completed a project on the issue of how quantitative and

qualitative research are combined in the social sciences,

as part of the Research Methods Programme of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

He contributed articles to a range of academic journals, including Journal of Management Studies, Human

Relations, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Leadership Quarterly, and American Behavioral

Scientist. He was a member of the ESRC’s Research

Grants Board and conducted research into effective leadership in higher education, a project funded by the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

Alan published widely in the field of social research.

Among his writings were Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS 17, 18 and 19: A Guide for Social Scientists (Routledge, 2011), with Duncan Cramer; Social

Research Methods (Oxford University Press, 2008); The

SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods

(Sage, 2004), with Michael Lewis-Beck and Tim Futing Liao; The Disneyization of Society (Sage, 2004);

Handbook of Data Analysis (Sage, 2004), with Melissa

Hardy; Understanding Research for Social Policy and

Practice (Policy Press, 2004), with Saul Becker; and

the SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, with David Buchanan (Sage, 2009). He edited the

Understanding Social Research series for the Open University Press.

Bill Harley is Professor of Management in the Department

of Management and Marketing at the University of Melbourne. Bill was awarded a PhD in political science from

the University of Queensland in 1995, for a dissertation

on the impact of changes in industrial relations legislation on labour flexibility at the workplace level. Prior to

undertaking his PhD, Bill was a graduate trainee with

the Australian government and subsequently worked for

some years in policy roles in Canberra. He has served as a

consultant to numerous national and international organizations, including the OECD and the ILO.

Bill’s academic research has been motivated by an

abiding interest in the centrality of work to human life.

Informed by labour process theory, his primary focus has

been on issues of power and control in the workplace.

Much of his published work has focused on the ways in

About the authors

which managerial policy and practice shape employees’

experience of work. Bill has also published a number of

papers on research methodology. His work has been published in journals including the British Journal of Industrial Relations, Journal of Management Studies, Industrial

xxix

Relations, and Work Employment and Society. Bill was

previously general editor of Journal of Management Studies and at the time of writing is on the editorial board of

the same journal and that of Academy of Management

Learning and Education and Human Relations.

ABOUT THE STUDENTS

AND SUPERVISORS

For this edition of the book we have fully updated the Student experience feature, in which undergraduate and

postgraduate students share their experiences of doing

business research. In addition to the three UK-based

undergraduates and one postgraduate student who were

interviewed for the second edition of this book, we have

interviewed another UK-based student and four business

degree students in Australia about their experiences of

doing a business research project. For those students

who completed their degrees in 2004/5, we provide an

update below on their careers to date. As we believe their

experience demonstrates, the skills involved in doing

business research are highly transferable into a range of

business careers and we are delighted to include details

of how they have progressed since doing their university

degrees. We are extremely grateful to all these individuals for their willingness be interviewed and we hope that

sharing what they have learned from this process with

the readers of this book will enable others to benefit from

their experience. Videos of the student interviews are

among the online resources that accompany this book.

Amrit Bains completed a degree in Business Management

with a year in industry at the University of Birmingham,

UK, in 2017. Amrit’s research question focused on understanding the causes and consequences of mental health

problems at work. His dissertation project involved

reviewing existing research on this topic, in the form of a

systematic literature review (as described in Chapter 5).

This method did not require him to collect original quantitative or qualitative data himself, but instead relied

on his analysis of existing material. Amrit’s dissertation

project highlights the importance of understanding the

methods used by researchers, so that you can evaluate

the quality of the claims that are made.

Lucie Banham completed an MA in Organization Studies

in 2005 at the University of Warwick, UK, where she had

previously studied psychology as an undergraduate. Her

dissertation project focused on how governments seek to

foster the development of enterprising behaviour among

students and young people. Her fieldwork concentrated

on the activities of a UK government-funded institute

responsible for promoting enterprise. Lucie’s qualitative research strategy combined participant observation,

unstructured and semi-structured interviews, and documentary data collection. When we spoke to Lucie again

in 2017, she had become a Director of Banham Security,

the largest supplier of burglary and fire prevention systems in London.

Jordan Brown completed an honours degree in Commerce

at Monash University Australia in 2017 after doing a

double degree in Arts and Business, also at Monash. Her

dissertation focus in her honours year was on authentic self-expression at work. Jordan adopted a quantitative research strategy and her data collection method

involved a correlational field study survey. She is planning to begin a PhD focusing on the aesthetics of art in

organizing resistance within political conflict.

Tom Easterling first spoke to us in 2005, having just com-

pleted an MSc in Occupational Psychology at Birkbeck

College, University of London, UK. He had been studying

part-time over two years, combining this with a full-time

job as an NHS manager in London. Tom’s dissertation

research project focused on wellbeing in the workplace,

focusing on telephone call centre workers. His research

involved a qualitative case study of a public-sector call

centre, where he interviewed people at different hierarchical levels of the organization. Tom is currently director

of the chair and chief executive’s office for NHS England

and works in London.

Anna Hartman completed a Master’s of Commerce in Mar-

keting at the University of Melbourne, Australia, in 2017.

Her interest in marketing ethics led her to focus her

research project on women who become commercial egg

donors and how these services are marketed to prospective consumers. Anna’s research strategy was qualitative

in nature; she conducted semi-structured interviews

via Skype with women who had been commercial egg

About the students and supervisors

xxxi

donors. She is now enrolled at Melbourne as a doctoral

student and is focusing on the market system dynamics

of commercial egg donation, using discourse analysis

and phenomenology.

the logistics company Gist as a part of their HR graduate

programme. She was promoted to HR manager before

taking a career break and travelling to Australia, where

she is an HR adviser at Lizard Island Resort.

Ed Hyatt, before studying for a PhD, worked in a variety

of industries, both public and private. His most extensive

experience was as a public procurement manager and

contracts officer for several US government agencies and

universities. When we spoke to him in 2017, Ed Hyatt was

completing a PhD at the University of Melbourne, Australia, in the field of human resource management, recruitment, and selection. His focus was on organizational

policies that promote a more fulfilling work experience

for both individuals and organizations, looking specifically at whether structured job interviews can enable

better person–organization fit. His quantitative research

strategy involved conducting online panel experiments

among hiring managers, using scales to measure their

behavioural responses.

Chris Phillips did his undergraduate degree in Commerce

at the University of Birmingham, UK, in 2004. His thirdyear dissertation investigated the career progression of

women employees in a global bank where he had done

an internship in his second year. His research questions

focused on understanding how and why women employees progress hierarchically within the bank, including

factors and barriers that affect their career progression.

His questions were informed by the concept of the ‘glass

ceiling’ which explores why women experience unequal

treatment that hinders career progression in organizations. His research strategy was qualitative and involved

semi-structured interviews. Chris works in London as a

marketing controller in Sky VIP, Sky’s customer loyalty

programme.

Karen Moore completed a Bachelor’s degree in Business

Alex Pucar did a dual Bachelor of Business degree major-

Administration and Management at Lancaster University, UK, in 2005. Her final-year research project came

about as the result of her third-year company placement,

when she worked in a human resources (HR) department. Karen became interested in the concept of person–

organizational culture fit. She carried out an audit of

the organizational culture in the company and explored

whether the recruitment and selection process operated

to ensure person–organization fit. Her mixed methods

research design involved a questionnaire and semi-structured interviewing. Following her degree, Karen joined

ing in Marketing, Management, and Economics at Monash

University, Australia. As part of this, he completed an

honours dissertation in 2017. He is now employed in

marketing. Alex’s research focused on understanding

how and why companies that start online make the decision to open physical stores—which is referred to as the

‘clicks to bricks’ strategy in retailing. His interest was on

the impact of this strategy on the growth and progression of small and medium enterprises. Alex’s research

strategy was qualitative and involved semi-structured

interviewing.

GUIDED TOUR OF TEXTBOOK

FEATURES

Chapter outline

Each chapter opens with a guide that provides a route

map through the chapter material and summarizes the

goals of each chapter, so that you know what you can

expect to learn as you move through the text.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

This chapter introduces some fundamental considerations in conducting business rese

outlining what we mean by business research and the reasons why we conduct it. The

three main areas:

t

Business research methods in context. This introduces issues such as the role of th

ethical considerations; debates about relevance versus rigour; and how political co

business research.

Key concept boxes

The world of research methods has its own language.

To help you build your research vocabulary, key terms

and ideas have been defined in Key concept boxes that

are designed to advance your understanding of the field

and help you to apply your new learning to new research

situations.

1.1 KEY CONCEPT

What is evidence-based managemen

Evidence-based management is ‘the systematic use of the best available evide

practice’ (Reay et al. 2009). The approach is proposed as a way of overcoming

et al. 2016), which seeks to address the problem whereby, according to some

insufficiently relevant to practice. The concept developed during the 1990s to

was subsequently applied in other fields such as education (Petticrew and Rob

Research in focus boxes

It is often said that the three most important features to

look for when buying a house are location, location, location. A parallel for the teaching of research methods is

examples, examples, examples! Research in focus boxes

are designed to provide a sense of place for the theories

and concepts being discussed in the chapter text, by providing real examples of published research.

1.3 RESEARCH IN FOCUS

A research question about gender bia

towards leaders

The research question posed in the title of the article by Elsesser and Lever (20

female leaders persist?’ They begin by reviewing the literature, which suggests

female leaders still persist. However, they question whether prior research can

Student experience boxes

The student experience boxes provide personal insights

from a range of individuals; they are based on interviews

with real research students, business school supervisors,

and lecturers from business schools around the UK. In

this way we hope to represent both sides of the supervision relationship, including the problems faced by students and how they are helped to overcome them and

the advice that supervisors can provide. These boxes will

help you to anticipate and resolve research challenges as

you move through your dissertation or project.

STUDENT EXPERIENCE

The influence of personal values on

Many students are influenced in their choice of research subject by their ow

This can be positive, because it helps to ensure that they remain interested i

the project. Amrit explained that his decision to focus on the topic of mental

was

Guided tour of textbook features

xxxiii

Tips and skills boxes

TIPS AND SKILLS

Tips and skills boxes provide guidance and advice on

key aspects of the research process. They will help you

to avoid common research mistakes and equip you with

the necessary skills to become a successful business

researcher in your life beyond your degree.

Making a Gantt chart for your researc

One way to keep track of your research project is by using a Gantt chart. The h

the total time span of the project divided into units such as weeks or months. T

involved in the project. An example is provided in Figure 4.1. Shaded squares o

of time you expect to spend on each task. The filled-in squares may overlap, fo

Thinking deeply boxes

4.1 THINKING DEEPLY

Business research methods can sometimes be complex:

to raise your awareness of these complexities, thinking

deeply boxes feature further explanation of discussions

and debates that have taken place between researchers. These boxes are designed to take you beyond the

introductory level and encourage you to think in greater

depth about current research issues.

Marx’s sources of research questions

Marx (1997) suggests the following possible sources of research questions:

t Intellectual puzzles and contradictions.

t The existing literature.

t Replication.

Checklists

CHECKLIST

Questions to ask yourself when reviewing the

Many chapters include checklists of issues to be considered when undertaking specific research activities

(such as writing a literature review or conducting a focus

group), to remind you of key questions and concerns and

to help you progress your research project.

Key points

At the end of each chapter there is a short bulleted summary of crucial themes and arguments explored in that

chapter. These are intended to alert you to issues that are

especially important and to reinforce the areas that you

have covered to date.

Questions for review

Review questions have been included at the end of every

chapter to test your grasp of the key concepts and ideas

being developed in the text, and help you to reflect

on your learning in preparation for coursework and

assessment.

Is your list of references up to date? Does it include the most recentl

What literature searching have you done recently?

What have you read recently? Have you found time to read?

!

?

KEY POINTS

●

Quantitative research can be characterized as a linear series of step

conclusions, but the process described in Figure 8.1 is an ideal typ

departures.

●

The measurement process in quantitative research entails the searc

●

Establishing the reliability and validity of measures is important for

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

●

Why are ethical issues important in the conduct of business resear

●

Outline the different stances on ethics in social research.

●

How helpful are studies such as those conducted by Milgram, Han

understanding the operation of ethical principles in business resea

GUIDED TOUR OF THE

ONLINE RESOURCES

www.oup.com/uk/brm5e/

For students

Research guide

This interactive research guide takes you step by step

through each of the key research phases, ensuring that

you do not overlook any research step and providing

guidance and advice on every aspect of business research.

The guide features checklists, web links, research activities, case studies, examples, and templates and is conveniently cross-referenced back to the book.

Interviews with research students

Learn from the real research experiences of students who

have recently completed their own research projects!

Download video-recorded interviews with undergraduate and postgraduate students from business schools

in the UK and Australia, and hear them describe the

research processes they went through and the problems

they resolved as they moved through each research phase.

Multiple-choice questions

The best way to reinforce your understanding of research

methods is through frequent and cumulative revision.

To support you in this, a bank of self-marking multiplechoice questions is provided for each chapter of the text,

and they include instant feedback on your answers to help

strengthen your knowledge of key research concepts.

Web links

A series of annotated web links organized by chapter

are provided to point you in the direction of important

articles, reviews, models, and research guides. These will

help keep you informed of the latest issues and developments in business research.

Guide to using Excel in data analysis

This interactive workbook takes you through step-by-step

from the very first stages of using Excel to more advanced

topics such as charting, regression, and inference, giving

guidance and practical examples.

Guided tour of the online resources

For registered adopters of the text

NEW: test bank

Test banks for every chapter are available with this fifth

edition which includes a mixture of multiple-choice,

true or false, and multiple-answer questions. There are

10-15 questions per chapter available, providing you with

ready-made assessments for your students.

NEW: discussion questions

Each chapter is now accompanied by two discussion

questions with suggested responses and guidance, to

help you plan seminars or lectures and generate debate.

Case studies

Fully refreshed for this edition, varied, real-life case studies illustrate some of the key concepts discussed in the

chapters, helping students better understand research in

a wider context and saving you time in finding additional

examples.

Lecturer’s guide

A comprehensive lecturer’s guide is included to assist

both new and experienced instructors in their teaching.

It includes reading guides, lecture outlines, further coverage of difficult concepts, and teaching activities, and is

accompanied by instructions on how the guide may be

most effectively implemented in the teaching program.

PowerPoint® slides

A suite of customizable PowerPoint slides is included for

use in lecture presentations. Arranged by chapter theme

and tied specifically to the lecturer’s guide, the slides

may also be used as hand-outs in class.

FIGURE 9.1

Figures and plates from the text

All figures and plates from the text have been provided

in high resolution format for downloading into presentation software or for use in assignments and exams.

Steps in planning a social survey

s

r

g

s

Decide on topic/area to be researched

Review literature/theories relating to topic/area

xxxv

ABOUT THE BOOK

The focus of the book

This is a book that will be of use to all students in business schools who have an interest in understanding

research methods as they are applied in management

and organizational contexts. Business Research Methods gives students essential guidance on how to carry

out their own research projects and introduces readers

to the core concepts, methods, and values involved in

doing research. The book provides a valuable learning

resource through its comprehensive coverage of methods

that are used by experienced researchers investigating

the world of business, as well as introducing some of the

philosophical issues and ethical controversies that these

researchers face. So, if you want to learn about business

research methods, from how to formulate research questions to the process of writing up your research, Business

Research Methods will provide a clear, easy-to-follow, and

comprehensive introduction.

Business Research Methods is written for students of

business and management studies. The book originally

grew out of the success of Alan Bryman’s book Social

Research Methods. Writing the fifth edition of Business

Research Methods has entailed changes enabled in part

by bringing in the third author, Bill Harley. A key purpose of the authors has been to further internationalize the book’s coverage, based on Bill’s expertise in the

Australian business and management context. A further

aim has been to streamline the text, for example by integrating the coverage of online research throughout the

chapters, rather than having a separate chapter on it as in

previous editions of the book. We have also sought to be

responsive to the needs of today’s students and lecturers,

who require a guide to business research methods that

is comprehensive and informed by the latest developments, but which also remains concise and focused. In so

doing our goal has been to ensure that Business Research

Methods remains a streamlined, up-to-date, and readable

textbook.

Because this book is written for a business school audience, it is intended to reflect a diverse range of subject

areas, including organizational behaviour, marketing,

strategy, organization studies, and human resource management (HRM). In using the term ‘business research

methods’, we have in mind the kinds of research methods that are employed in these fields, and so we have

focused primarily on methods that are informed by other

disciplines within the social sciences such as sociology,

anthropology, and psychology. Certain areas of business

and management research, such as economics and financial and accounting research, are not included within our

purview. These are self-contained fields with their own

traditions and approaches that do not mesh well with the

kinds of methods dealt with in this book.

In addition to providing students with practical advice

on doing research, the book also explores the nature

and purpose of business and management research. For

example:

•

What is the aim or purpose of business research?

Is it conducted primarily in order to find ways of

improving organizational performance through

increasing effectiveness and efficiency?

Or is it mainly about increasing our understanding

of how organizations work, and their impact on

individuals and on society?

•

Who are the audiences of business research?

Is business research conducted primarily for managers?

If not, for whom else in organizations is it conducted?

•

Is the purpose of business research to further the academic development of the field?

•

What is the politics of management research, and how

does this frame the use of different methods and the

kinds of research findings that are regarded as legitimate and acceptable?

•