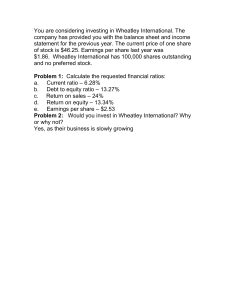

Analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’ Before we analyse ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’, though, here’s the text of the poem. ’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our sable race with scornful eye, ‘Their colour is a diabolic die.’ Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train. On Being Brought from Africa to America’ is a poem by Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753-84), who was the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral appeared in 1773 when she was probably still in her early twenties. Because Wheatley stands at the beginning of a long tradition of African-American poetry, we thought we’d offer some words of analysis of one of her shortest poems. Background and summary Wheatley had been taken from Africa (probably Senegal, though we cannot be sure) to America as a young girl, and sold into slavery. A Boston tailor named John Wheatley bought her and she became his family servant. The young Phillis Wheatley was a bright and apt pupil, and was taught to read and write. She learned both English and Latin. Even at the young age of thirteen, she was writing religious verse. As Michael Schmidt notes in his wonderful The Lives Of The Poets, at the age of seventeen she had her first poem published: an elegy on the death of an evangelical minister. Wheatley was fortunate to receive the education she did, when so many African slaves fared far worse, but she also clearly had a nature aptitude for writing. She was freed shortly after the publication of her poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, a volume which bore a preface signed by a number of influential American men, including John Hancock, famous signatory of the Declaration of Independence just three years later. Indeed, she even met George Washington, and wrote him a poem. However, her book of poems was published in London, after she had travelled across the Atlantic to England, where she received patronage from a wealthy countess. She died back in Boston just over a decade later, probably in poverty. In the short poem ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’, Phillis Wheatley reminds her (white) readers that although she is black, everyone – regardless of skin colour – can be ‘refined’ and join the choirs of the godly. Analysis Let’s take a closer look at ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’, line by line: ’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Wheatley casts her origins in Africa as non-Christian (‘Pagan’ is a capacious term which was historically used to refer to anyone or anything not strictly part of the Christian church), and – perhaps controversially to modern readers – she states that it was ‘mercy’ or kindness that brought her from Africa to America. This is obviously difficult for us to countenance as modern readers, since Wheatley was forcibly taken and sold into slavery; and it is worth recalling that Wheatley’s poems were probably published, in part, because they weren’t critical of the slave trade, but upheld what was still mainstream view at the time. Taught my benighted soul to understand Wheatley casts her own soul as ‘benighted’ or dark, playing on the blackness of her skin but also the idea that the Western, Christian world is the ‘enlightened’ one. She is writing in the eighteenth century, the great century of the Enlightenment, after all. That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Contrasting with the reference to her Pagan land in the first line, Wheatley directly references God and Jesus Christ, the Saviour, in this line. She sees her new life as, in part, a deliverance into the hands of God, who will now save her soul. Some view our sable race with scornful eye, The word ‘sable’ is a heraldic word being ‘black’: a reference to Wheatley’s skin colour, of course. But here it is interesting how Wheatley turns the focus from her own views of herself and her origins to others’ views: specifically, Western Europeans, and Europeans in the New World, who viewed African people as ‘inferior’ to white Europeans. ‘Their colour is a diabolic die.’ The word ‘diabolic’ means ‘devilish’, or ‘of the Devil’, continuing the Christian theme. ‘Die’, of course, is ‘dye’, or colour. Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, Wheatley implores her Christian readers to remember that black Africans are said to be afflicted with the ‘mark of Cain’: after the slave trade was introduced in America, one justification white Europeans offered for enslaving their fellow human beings was that Africans had the ‘curse of Cain’, punishment handed down to Cain’s descendants in retribution for Cain’s murder of his brother Abel in the Book of Genesis. May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train. But Wheatley concludes ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’ by declaring that Africans can be ‘refin’d’ and welcomed by God, joining the ‘angelic train’ of people who will join God in heaven. Wheatley begins by crediting her enslavement as a positive because it has brought her to Christianity. While her Christian faith was surely genuine, it was also a "safe" subject for an enslaved poet. Expressing gratitude for her enslavement may be unexpected to most readers. The word "benighted" is an interesting one: It means "overtaken by night or darkness" or "being in a state of moral or intellectual darkness." Thus, she makes her skin color and her original state of ignorance of Christian redemption parallel situations. She also uses the phrase "mercy brought me." A similar phrase is used in the title "on being brought." This deftly downplays the violence of the kidnapping of a child and the voyage on a ship carrying enslaved people, so as to not seem a dangerous critic of the system—at the same time crediting not such trade, but (divine) mercy with the act. This could be read as denying the power to those human beings who kidnapped her and subjected her to the voyage and to her subsequent sale and submission. She credits "mercy" with her voyage—but also with her education in Christianity. Both were actually at the hands of human beings. In turning both to God, she reminds her audience that there is a force more powerful than they are—a force that has acted directly in her life. She cleverly distances her reader from those who "view our sable race with scornful eye"— perhaps thus nudging the reader to a more critical view of enslavement or at least a more positive view of those who are held in bondage. "Sable" as a self-description of her as being a Black woman is a very interesting choice of words. Sable is very valuable and desirable. This characterization contrasts sharply with the "diabolic die" of the next line. "Diabolic die" may also be a subtle reference to another side of the "triangle" trade which includes enslaved people. At about that same time, the Quaker leader John Woolman is boycotting dyes in order to protest enslavement. In the second-to-last line, the word "Christian" is placed ambiguously. She may either be addressing her last sentence to Christians—or she may be including Christians in those who "may be refined" and find salvation. She reminds her reader that Negroes may be saved (in the religious and Christian understanding of salvation.) The implication of her last sentence is also this: The "angelic train" will include both White and Black people. In the last sentence, she uses the verb "remember"—implying that the reader is already with her and just needs the reminder to agree with her point. She uses the verb "remember" in the form of a direct command. While echoing Puritan preachers in using this style, Wheatley is also taking on the role of one who has the right to command: a teacher, a preacher, even perhaps an enslaver. Form Iambic pentameter is a metrical pattern in poetry consisting of five iambs per line. An iamb is a metrical foot comprising one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable. In iambic pentameter, each line has five pairs (or iambs) of syllables. An iamb is like a little heartbeat: du-DUM. The first syllable is light, and the second one is stressed or emphasized. So, in each line, you get that da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM pattern. It's a rhythmic structure that many poets use because it sounds natural and flows smoothly. ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’ is written in iambic pentameter and, specifically, heroic couplets: rhyming couplets of iambic pentameter, rhymed aabbccdd. We can see this metre and rhyme scheme from looking at the first two lines: ’Twas MER-cy BROUGHT me FROM my PA-gan LAND, Taught MY be-NIGHT-ed SOUL to UN-der-STAND Heroic couplets were used, especially in the eighteenth century when Phillis Wheatley was writing, for verse which was serious and ‘weighty’: heroic couplets were so named because they were used in verse translations of classical epic poems by Homer and Virgil, i.e., the serious and grand works of great literature. In using heroic couplets for ‘On Being Brought from Africa to America’, Wheatley was drawing upon this established English tradition, but also, by extension, lending a seriousness to her story – and her moral message – which she hoped her white English readers would heed. Read more about poetic forms in your individual study time to jog your memory. Themes Wheatley explores prominent themes of religion, freedom, and implied equality In her poem "On Being Brought from Africa to America," Wheatley talks a lot about God, freedom, and a sort of fairness. Even though the main idea is how God changed her life during slavery, she also hints that everyone could experience something similar. Wheatley believes that finding God made her life better, and she thinks it could do the same for others. Literary Devices Phillis Wheatley's poem "On Being Brought from Africa to America" showcases a variety of poetic devices, contributing to its literary richness. The poetic devices mentioned below collectively contribute to the formal structure, musicality, and thematic depth of the poem, allowing Wheatley to express her complex ideas about race, religion, and identity compellingly and artfully. 1. Iambic Pentameter: The poem is written in iambic pentameter, a metrical pattern that consists of five pairs of syllables in each line, with the stress on the second syllable of each pair. 2. Heroic Couplet: Wheatley structures the poem using heroic couplets, which are pairs of rhymed lines written in iambic pentameter. This choice of form lends a sense of rhythm and unity to the poem. 3. End Rhyme: The poem utilizes a simple and consistent rhyme scheme of AABBCCDD, with each pair of lines rhyming with the subsequent pair. This creates a musical quality and a sense of completion at the end of each couplet. 4. Enjambment: Wheatley employs enjambment, where a sentence or phrase runs over the end of a line and into the next, in several places throughout the poem. This technique creates a sense of continuity and fluidity in the reading experience. 5. Allusion: The poem contains an allusion to the Christian concept of salvation and redemption, particularly in the lines "Some view our sable race with scornful eye, / 'Their color is a diabolic die'". This allusion serves to emphasize the theme of Christianity and its potential for universal salvation. Allusion: The poem contains an allusion to the Christian concept of salvation and redemption, particularly in the lines "Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, / May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train." This allusion serves to emphasize the theme of Christianity and its potential for universal salvation 6. Personification: Wheatley personifies "mercy" in the first line, stating that it brought her to America. This personification adds a figurative or metaphorical layer to the poem, inviting the reader to consider the abstract concept of "mercy" as an active force in the poet's life. 7. Assonance: The poem uses assonance, the repetition of vowel sounds in the same line, such as in the lines "Taught my benighted soul to understand" and "May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train”. 5. Caesura: The poem uses caesura, a pause or break in the middle of a line, to create emphasis and rhythm, such as in the line "Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain". Useful References: [1] https://literarydevices.net/on-being-brought-from-africa-to-america/ [2] https://www.storyboardthat.com/lesson-plans/on-being-brought-from-africa-to-america-byphillis-wheatley/literary-elements [3] https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/poetry/on-being-brought [4] https://www.litcharts.com/poetry/phillis-wheatley/on-being-brought-from-africa-to-america [5] https://www.learningforjustice.org/classroom-resources/texts/on-being-brought-from-africato-america