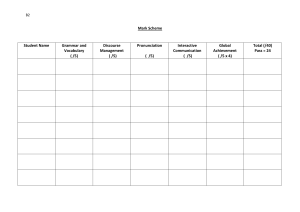

842453 research-article2019 DCM0010.1177/1750481319842453Discourse & CommunicationMakki Article ‘Discursive news values analysis’ of Iranian crime news reports: Perspectives from the culture Discourse & Communication 2019, Vol. 13(4) 437­–460 © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481319842453 DOI: 10.1177/1750481319842453 journals.sagepub.com/home/dcm Mohammad Makki University of New South Wales, Australia; University of Wollongong, Australia Abstract This article is concerned with ‘how’ newsworthiness is constructed linguistically/discursively in a sample of Iranian crime and misbehaviour reports. This is new as both linguistic analysis of ‘crime reports’ and the context of ‘Iranian journalism’ are among under-researched areas. Onemonth worth editions of two Iranian/Farsi language newspapers were collected, and the data were analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively with reference to the analytical framework of Bednarek and Caple. While the quantitative analysis showed the construction of Eliteness as the most frequent news value in both newspapers, there were differences in the construction of news values between the newspapers. Qualitative analysis of the data also showed the construction of news values in line with the sociocultural values prevalent in the society as well as the possible role of state and political authorities. Keywords Crime reports, discourse analysis, DNVA, Iranian journalism, news values, sociocultural, crime Introduction This article is concerned with the notion of newsworthiness and how it is constructed in Iranian/Farsi language crime news reports with reference to the emerging body of work on discursive news values analysis (DNVA) from Bednarek and Caple (2017). In a way, this article attempts to answer the call from Bednarek and Caple (2017) to investigate this linguistic/discursive framework (DNVA) in ‘other’ languages and cultures so as to enable a fuller cross-cultural comparison going beyond English language publications Corresponding author: Mohammad Makki, Faculty of Social Sciences, School of Education, Level 3 Building 67 McKinnon Building, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia. Emails: momaki1986@gmail.com; mmakki@uow.edu.au 438 Discourse & Communication 13(4) (p. 237). It can be said that this article is novel in two ways: first, it provides some discursive analysis of crime and misbehaviour reports which have not generally received much attention in discourse analysis studies, except for a very few studies within critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Catalano, 2014; Machin and Mayr, 2012); second, it attempts to shed some light on the application of the newly developed DNVA to the Iranian context and to the Persian/Farsi language newspapers. Crime and misbehaviour news reports have been chosen as a typical form of news, that is, they mainly contain the ‘basic news value’ of Negativity1 (Bell, 1991: 156); they form the ‘essence’ of news journalism, as crime and misbehaviour is among the subject areas which has been at the heart of news journalism since it emerged in its modern form in the early 17th century (Conboy, 2004). There have been numerous studies on the representation of crime, criminals and crime fighting in sociology, criminology and media studies (see classical studies of Chibnall, 1977; Cohen, 1972; Hall et al., 1978; Reiner, 2007; Schlesinger and Tumber, 1994; Young, 1971). There have also been studies which focused on the seriousness of the offence and its relationship to the cultural typification of victims and criminals as the criteria to be covered in the media (Chermak and Chapman, 2007), and there are studies which focus on the representation of the police force in the media, which even sometimes exaggerate police effectiveness (see Innes, 1999; Reiner, 2010). On the other hand, Iran, with its unique sociopolitical context in which the state supposedly heavily controls the media and its institutions, has always been an interesting case for research (see Faris and Rahimi, 2015; Khiabany, 2010; Khosravinik, 2015; Shahidi, 2007). Iran, like other Islamic countries, favours the ‘Maslahah principle’ – what is good for the society – as journalists are expected to report on events that have positive values for the society and humanity (Muchtar et al., 2017; Steele, 2013). Iranian Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, has always recommended journalists to ‘report good, positive and hopeful news’ (Iranian Students’ News Agency [ISNA], 1999). Thus, it would be interesting to find out how crime and misbehaviour news reports, with the inherent feature of Negativity as their prerequisite, will be reported in Iranian newspaper journalism. It is a country where the media generally operate under strict screening and supervisory procedures, and defiant media will be closed down with little compromise (Khiabany, 2010; Shahidi, 2007). Given this status of media and newspapers in Iran, it will be interesting to find out if ‘the potential news value of events depends on a given sociocultural system that assigns them value’ (Bednarek and Caple, 2017: 51). To be more precise, this research will investigate the construction of news values in the Iranian context to see if the Iranian/Islamic media system has affected the coverage of crime news reports. So far, the bulk of discourse analysis studies of the Iranian journalistic context has centred on the representation of Iran’s contentious nuclear issue in the Iranian, US and British publications through the lens of CDA (Behnam and Zenouz, 2008; Izadi and Saghaye-Biria, 2007; Khosravinik, 2015; Koosha and Shams, 2005; Rasti and Sahragard, 2012). There is also a growing body of research attending to the structural properties of Iranian Persian news texts in general and crime news reports in particular (Makki and White, 2018; Rafiee et al., 2018; White and Makki, 2016). Makki 439 However, how news values are constructed in published crime news reports with reference to the linguistic resources available has not yet been explored in a study of the Iranian context and in Farsi/Persian language newspapers. This article examines the types of news values and how they are construed2 and if Persian/Farsi language of the newspaper might construe news values differently from what has been already discussed in the literature on English language news reporting (Bednarek, 2015, 2016; Bednarek and Caple, 2014, 2017). In other words, the focus is on the extent to which the ‘sociocultural’ Iranian context will affect the discursive mechanism of news values in a news report (Bednarek and Caple, 2017; Parks, 2018). News values: A brief overview The notion of ‘newsworthiness’ or what journalists assessed to be worthy of coverage as news is discussed and critiqued extensively in the literature (for a thorough review of the newsworthiness literature, consult Caple, 2018; Caple and Bednarek, 2013). This notion has become popular in journalism studies since the first systematic categorization of news values or ‘factors’ by Galtung and Ruge (1965). Following their seminal study, various approaches emerged in journalism literature ranging widely from instinct and gut feelings, through selection criteria, to being intrinsic/inherent in events (Harcup and O’Neill, 2017; O’Neill and Harcup, 2009; Schultz, 2007). Even though linguists and discourse analysts have generally shown little interest in an in-depth analysis of news values, probably because of its perceived irrelevance to the linguistic analysis, there have been a few exceptions (Bednarek and Caple, 2012, 2017; Bell, 1991; Cotter, 2010; Fowler, 1991; Richardson, 2007; Van Dijk, 1988, 1998). Broadly speaking, four dimensions or perspectives are discussed on the analysis of news values: material, cognitive, social and discursive. In the material dimension, an event, itself, holds potential news value for a given community, and hence news values are intrinsic/inherent to the event and exist independently of the journalist. This dimension mainly ignores the role of sociocultural and political factors as they are not perceived to influence news values. In the cognitive dimension, news workers and audience members have beliefs about news values and newsworthiness (see Fowler, 1991; Van Dijk, 1988). Based on this perspective, ‘news values reflect economic, social and ideological values in the discourse reproduction of society through the media’ (Van Dijk, 1988: 120–121), but they are all controlled by cognitive constraints. Fowler’s (1991) own cognitive conceptualization of news values is ‘socially constructed’, and hence he recognizes the ‘social’ dimension of news values too (p. 15). In the social dimension, news values are applied as selection criteria in journalistic routines and practices. News workers apply news values as criteria in what events to publish and how to publish them. However, in this approach, the mediating role of practitioner/ journalist has been ignored and their role has been downplayed to just applying the ‘news values’ as if they are ready-made. Instead, news values can/should be constructed in the news text by the journalist who has a profound knowledge of the practice and the culture (Bell, 1991; Cotter, 2010). While different aspects of news values such as material, social or cognitive were highlighted in the earlier research, there is an issue which has been largely ignored in 440 Discourse & Communication 13(4) almost all of these studies – the role of language in the construction of news values. From this perspective, news values are viewed as being constructed discursively through language and other semiotic modes (such as visual modes and pictures). This approach is known as DNVA (Bednarek and Caple, 2017) and has been taken up in a large number of studies (e.g. Bednarek, 2016; Bednarek and Caple, 2012, 2014, 2017; Caple and Bednarek, 2016). The main point of DNVA is the close analysis of linguistic elements in the construction of news values in a news report, that is, how news values are constructed via semiotic modes of text and image (more on this in the next section). While there is a growing body of work examining English language news (Dahl and Fløttum, 2017; Molek-Kozakowska, 2017), DNVA has not been examined in many different cultural contexts, except for Chinese (Huan, 2016) and Italian (Fruttaldo and Venuti, 2017). It will be interesting to explore the application of DNVA in a non-Western, Middle Eastern context, like Iran. Analytical framework The ‘discursive’ approach to news values was developed in the early 2010s and has been more fully developed in Bednarek and Caple (2017). This approach mainly focuses on ‘how’ rather than ‘why’ news values are ‘constructed’ or ‘construed’ in news texts. One of the most important and distinguishing points for Bednarek and Caple, which I also follow in this study, is the ‘construction’ of news values in a news report – value that is ‘socioculturally assigned’, rather than [being] ‘natural’ or ‘inherent’ in the news reports (Bednarek and Caple, 2017: 51). Another important issue is how newsworthiness is constructed through linguistic and visual resources. In this study, the focus remains only on the linguistic aspects due to space restrictions. For example, Negativity together with Positivity may be constructed through the use of Attitudinal3 language (Martin and White, 2005), among other ways. Negativity and Positivity are both described as news values for Bednarek and Caple; as Feez et al. (2008) and White (1997) note, newsworthiness is about reporting both ‘destabilizing’ and ‘stabilizing’ events. Table 1 lists the news values with their linguistic resources, taken from the crime data of this study, adapted from Bednarek and Caple (2017). In selecting the news values labels, Bednarek and Caple (2017) choose not to reinvent the wheel, but rather include those that resonate most frequently among the established literature, and use labels that are ‘the most transparent and least ambiguous’ (pp. 53–55). However, what is new is the discursive manifestation of such values in the published news stories, and how they are linguistically constructed in the news reports. This article attempts to investigate the application of this linguistic inventory on a sample of Iranian Farsi language crime reports from two ideologically different news dailies. Specifically, it will be shown how each news value is constructed and what news values are more frequently construed in Iranian crime news reports. While this is not necessarily a quantitative study, numbers have been provided to give an idea about the possible frequency of each news value. More importantly, the linguistic functioning of the Iranian crime news reports is analysed to find out how each news value is construed. The role of sociocultural factors is examined to see if they have any effect on the construction of news values in the Iranian crime corpus. 441 Makki Table 1. News values and linguistic resources. News values Definitions and linguistic manifestations Consonance Event is discursively constructed as stereotypical through words and expressions (e.g. similarity with past: once again, just like before, previously … too) Event is discursively constructed as of high status and can include people, countries, institutions and so on (e.g. use of status markers and role labels: Colonel Mohammadi, the judge, Tehran’s prosecutor) Event is discursively constructed as having significant effects or consequences (e.g. descriptions of the consequences or effects of the event: leaves 10s of deaths) Event is discursively constructed as negative or positive (e.g. references to positive/negative emotions and behaviours as well as positive and negative lexis: ruthless, paedophile, murderer or forgiveness, mercy, skilful operation) Event is discursively constructed as having a personal or ‘human’ face (e.g. reference to ordinary, non-elite people, their emotions and descriptions of their appearances: Ali, Masoumeh, 8-year-old Atila, the tall, young boy) Event is discursively constructed as geographically or culturally near (e.g. explicit references to places near the target audience, references to places via deictics, cultural references: Tehran, Shiraz, here, this city, this country, Nowruz) Event is discursively constructed as being of high intensity or large scope (e.g. comparisons, quantifiers, intensifiers: more than …, hundreds of, 38 people were killed) Event is discursively constructed as timely, new, ongoing, current to the immediate situation (e.g. use of temporal reference, use of present and present perfect: today, yesterday, immediately, is available) Event is discursively constructed as unexpected, unusual, strange, rare (e.g. evaluations of unexpectedness, unusual happenings: surprising, suddenly, the girl survived the exorcism practice) Eliteness Impact Negativity/Positivity Personalization Proximity Superlativeness Timeliness Unexpectedness The newspapers and their sociopolitical context Two Iranian Persian language newspapers from different political spectrums were selected for this study, namely, Kayhan (meaning Galaxy) and Etemaad (meaning Trust). These newspapers are widely read throughout the country and have had a relatively stable history of publication. While possible differences according to political/ideological orientation were not a central concern of this article, nevertheless, it was felt wise to include data from newspapers representing this ideological range, just in case significant differences between these two newspapers did emerge. Kayhan is a media organization which has publications in different languages such as Persian, French, English and Arabic. Kayhan newspaper was originally founded by Mostafa Mesbahzadeh, a former senate member in 1942. It was considered to be one of the ‘Twin Giants’ with Ettela’at (meaning ‘information’) before the Islamic Revolution in 1979 442 Discourse & Communication 13(4) (Shahidi, 2007: 3) and among the ‘big four’ after the Islamic Revolution (Khiabany, 2010). The status, objectives, policies and even the editorial team of the newspaper have undergone fundamental changes in the passage of time and especially before and after the Islamic Revolution. After the Islamic Revolution, it underwent screening procedures in which 30 journalists of the newspaper were expelled and the newspaper came officially under the control of the Islamic Association (Shahidi, 2007: 38). Kayhan is typically seen as a conservative newspaper which supports Sharia laws and a political theocratic system to the extent that it is ‘in favour of total Islamization of public and private life in Iran, bringing all aspects of public life under Shari’a’ (Khiabany, 2010: 38). It is considered a ‘flagship paper for radical conservative voices in the Islamic Republic of Iran … and promotes discourses of anti-American/anti-Westernism and political Islam’ (Khosravinik, 2015: 140). According to Khiabany, Kayhan is against any liberalization policy and supports the intervention of state in the economy. In terms of government funding and subsidies, it was revealed that during 1989 to 2003, the government had provided the total sum of 368 million dollars cash to press, 107 million dollars of which went to only Kayhan (Shahidi, 2007: 78). Kayhan, undoubtedly, is one of the most important (if not the most) Iranian news dailies with its long history of publication and its alleged affiliation with the Supreme Leader. It has also been at the centre of attention in a number of other publications and discourse analysis studies (see Khosravinik, 2015; Shahidi, 2007). Etemaad, on the other hand, is a relatively newer publication with its affiliation to the Reformists. The Reformists, or liberals, who arose after Hojatol Eslam Mohammad Khatami took the presidential office in 1997, started a movement called the ‘Reform Movement’ between 1997 and 2005. They mainly support the freedom of press and liberalization of the economy and negotiations with the West (see Semati, 2008; Shahidi, 2007). Etemaad is typically seen as a liberal newspaper supporting reforms and dialogues with the West. It is considered the oldest Reformist newspaper in Iran which was founded in 2002 by a member of National Trust Party, Elyas Hazrati, who is still the managing editor. It was founded at a time of turmoil and suppression of the press. Etemaad has been banned from publication twice by the Press Supervisory Council and the Judiciary System, once in March 2010 on publication of a story of police attacking Tehran University after the 2009 contentious presidential election. After its re-publication, it was banned again for unknown reasons on 20 November 2011, which lasted for 2 months. One reason for choosing this newspaper is that, despite these closures, it has had a reasonably stable history of publication, at least relative to other reformist newspapers; second was the availability of all its materials online and in the exact print layout. This made the process of data collection easier and more convenient. Despite possible ideological and political differences between the two newspapers, they should follow the same specific rules and regulations to be able to continue publishing. For example, as Bahrampour (2004) outlines, post-revolutionary Islamic government believed that media practices are not the right of every individual but the authorized ones, and hence supervision and control of the press is a requirement in this context. Data collection procedures and analysis Data used in this study were the crime and misbehaviour reports published in Etemaad and Kayhan, over a period of 1 month, from 31 October 2013 to 30 November 2013. 443 Makki Table 2. The number of local and overseas crime reports in the newspapers with the total number of words in parenthesis. Etemaad Kayhan Local crime reports Overseas crime reports 110 (42,944) 38 (9411) 17 (2325) 19 (3113) Reports of crime and misbehaviour referred to all news reports of murder, theft, extortion, robbery, kidnapping, swindling and so on. This is related to what White (1997) terms ‘normative breach’ – that is, where there is human behaviour which breaches legal or ethical norms (p. 3). Crime and misbehaviour reports of the whole month, mainly published in the police rounds section, were collected. To achieve this, all 30 editions (to be exact 26 as the newspapers would not be published on the weekends and public holidays) were investigated carefully to cull out the crime news reports published in the newspapers. Not only the news items published in the police rounds section had to be collected but also other sections of the newspaper had to be examined to check whether there was any crime report published elsewhere. This fact – that is, the place, page, exact space, colour and font – could also contribute to how a news item was construed as newsworthy (Bednarek and Caple, 2012; Bell, 1991), but this element was not brought to the news values analysis. The main focus of this article should remain on the ‘linguistic properties’ of the texts and in Bednarek’s (personal communication) terms, on the ‘meaning-potential of published texts’. The emphasis remained on the collection of only ‘news reports’ of the two newspapers which is generally assumed to be the most ‘objective’ news genre (see Mindich, 1998). Two ideologically opposing newspapers were selected to provide a better and comprehensive array of Iranian newspaper journalism so that the element of bias in the newspaper’s selection of news reports can be ruled out. All local and overseas crime and misbehaviour news reports were collected, and the total number of words in each section was also calculated within Microsoft Word (Table 2). Having collected and counted all crime reports and the words, the inventory of linguistic devices outlined earlier (Table 1) was applied to the reports based on the co-text and the cultural context. Due to the original Persian-Farsi language4 of news reports, the researcher was not able to use the UAM Corpus (O’Donnell, 2015) or any other tool to code the data; instead, the coding was done manually and from the news reports on the Microsoft Word directly. The unit of coding for analysis was counting of news values per occurrence/instance; this means that if the lexical item was repeated in the headline and lead, it was counted twice or any number of times it occurred in the news text. Then, all news reports were coded for each news value in turn. This study started with Consonance and all news reports were coded, and then with Eliteness and all reports, and this went on for each news value. This focus on one news value at a time allows for a more focused, systematic and consistent analysis (Bednarek, 2015). While the author is responsible for coding the data, he consulted with various academics in cases of ambiguity, over a long period of time (during the completion of the PhD from which this article is one part of). So, the data were re-coded multiple times to ensure intra-coder reliability. Inter-coder agreement might not be the optimum for this research as ‘it would not have reduced the “subjectivity” of the coding per se’ (Bednarek, 2015: 6). Instead, the focus is on ensuring 444 Discourse & Communication 13(4) that coding is consistent and transparent, and can be justified with an argument. In analysing the data, a few caveats should be noted. First, the category of Negativity was excluded in the analysis as not only it has been ‘the basic news value’ (Bell, 1991) but also it is unmanageable to keep track of all Negativity instances in crime and misbehaviour reports because there are numerous instances of ‘kill’, ‘murder’, ‘steal’, ‘rape’, ‘criminal’ and other negative lexis and events. In other words, the news value of Negativity was predetermined in the corpus design. Finding out that Negativity is constructed is neither surprising nor is it independent from the criteria used to collect the data in the first place. Second, all cities named in the reports were counted as Proximity as construction of this news value would mainly depend on the target audience, possibly encompassing the whole population in Iran; this is a nationally circulated newspaper with even a wider reach via the Internet for Iranians living abroad. For the analysis of the news report, first the headline and lead and then the body of the news report were coded, and as noted, each instance/occurrence was counted. Then, due to the large difference between the size of Etemaad’s and Kayhan’s crime reports, raw frequency numbers were normalized per 10,000 words to neutralize the significant difference in the number of crime and misbehaviour reports between the newspapers. It is common to normalize raw frequencies to a common base (10,000 words for small corpora and 1,000,000 for large corpora) when comparing corpora of markedly different sizes (McEnery et al., 2006). Results and quantitative findings The tables 3 and 4 below show the normalized frequency of constructed news values in both newspapers and in both local and overseas events. However, this difference is not the focal point of this article as it is not a comparative study between the newspapers. Rather, the intention is to provide some perspectives into the concept of newsworthiness in Iranian crime news reports. The normalized frequency of constructed news values in the Iranian newspapers Etemaad and Kayhan shows that Eliteness, Timeliness, Proximity, Personalization and Positivity are the most frequently constructed news values in Etemaad’s local crime and misbehaviour reports, respectively, while Eliteness, Proximity, Positivity and Timeliness are the most frequently constructed ones in Kayhan’s. This high occurrence of Positivity in both newspapers shows the focus of crime reports on the ‘detention’ of criminals and ‘restoration of order’ (Feez et al., 2008; White, 1997), and mostly positive assessments of the police force, Judiciary System and similar authorities. Most of the news values (Eliteness, Positivity, Proximity, Superlativeness and Timeliness) have been constructed more in Kayhan than in Etemaad, while Consonance, Personalization and Unexpectedness have been constructed fairly equal between the newspapers (e.g. 12 and 11 for Consonance). The analysis of overseas news reports shows that Eliteness, Proximity and Timeliness are the most frequent news values for Etemaad, while Personalization and Positivity are added to the previous three as the most frequent news values in Kayhan. Interestingly, while there are a few instances of Unexpectedness constructed in Etemaad’s local events through assessments of unexpectedness, there is none in overseas reports. Kayhan, though, covered a few overseas events which construed Unexpectedness such as ‘police raiding an exorcism practice’. Makki 445 Overall, Eliteness seems to be the most frequently constructed news value in the newspapers for both local and overseas events. Also, Positivity seems to have been constructed significantly more in Kayhan’s coverage of events than in Etemaad’s. On the other hand, Impact was construed more in Etemaad than in Kayhan, in both local and overseas events. Also, Timeliness, Superlativeness and Proximity have been construed more in Etemaad’s overseas reports than in Kayhan’s while the case was totally opposite in local events. Qualitative analysis of the crime reports The analysis of a month worth of crime reports demonstrated the construction of all the above-mentioned news values through various linguistic resources. There were also linguistic cues which could construe different news values, in line with the sociocultural expectations, from what is normally expected (Bednarek and Caple, 2017; Parks, 2018). For example, there are terms and expressions in the crime reports which totally neutralize the negativity of the news report and also, to some extent, make it positive (e.g. ‘be martyred’ instead of ‘be killed’ for police force). These religious terms can also construe other news values such as Eliteness when they refer to important rituals (see ‘Eliteness’ section). There are also examples in which more than one news value has been construed (e.g. Impact and Superlativeness). Other news values have been constructed through various linguistic devices which appear mainly to be influenced by the Iranian/Islamic sociocultural context. Consonance This news value was constructed mainly through references to general knowledge and stereotypes held by the society about specific groups, people and populations, as well as some suggestions to the similarities with past. The latter issue is relevant to the data when similar and earlier cases of misconduct from the criminal have been outlined. So, stereotypes of criminals as ‘re-offenders’ or perpetrators who keep offending will most likely construct Consonance in the sample of data. Words and expressions used show the previous negative record of the perpetrator in terms of stealing, robbery and earlier history of imprisonment (Figure 1). The highlighted part in example 1 conforms to the stereotypical belief that Iranians are so emotional (at least commonly held among Iranians), especially at times of grieving and sadness (Good and Good, 1988). The report takes note of this part as it encourages the police force to try and detain the culprit as soon as they can in order to alleviate the pain of people. The second and third examples, which are more typical of Consonance in the Iranian context, refer to the similar record of thefts by the perpetrator in which he was detained a year ago. These examples are plentiful in the data in which the criminal has previous record of theft, larceny, violence and extortion, and the criminal seems to be a jailbird. References to the previous record might function to distance the reader from the criminal and will be likely to construct the criminal as an ‘other’, outsider or different members of society. These criminals are shown as ‘repeat offenders’ or ‘career criminals’, and hence the news reports appear to construe Consonance with outlining 446 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Figure 1. Examples of Consonance in the corpus.5 similarity with the past, ‘a year ago … too’, ‘has a previous record of …’, as if these criminals are re-offending and there is little or no reforming this kind of person. There is a famous saying/stereotype for these criminals in the society: ‘you may end them but you will not mend them’. Eliteness This is one of the most frequently constructed news values in the corpus. Eliteness is constructed in most of the crime reports through the presence of a police authority of some rank as well as occasional references to courts, judges, lawyers and prosecutors. There have been also some news reports of high-status individuals being assassinated and murdered. References to well-known rituals and sacred places and events are among other devices for construing this news value. Also, in terms of overseas reports, there are some news reports on riots and murders in high-status countries like the United States and the United Kingdom (Figure 2). The abundance of cases like example 4 and numerous references to courts, prosecutors, police officers, colonels and lawyers are typical of Iranian crime news reports. In fact, individuals themselves are not generally known to the public, but the role labels and their social status and ranks have made them elite individuals or places: ‘Judge Asghar Abdollahi’, ‘Crime Court in Tehran’, ‘Zabol’s6 prosecutor’. Also, in example 6, Muharram7 month, which is a sacred month for the Shiite, can be considered an example of Eliteness. There are other examples in which Tasua and Ashura8 have been discussed. These religious events are of very high status for all the Shiite community and along with the Muharram month can be included as linguistic resources constructing Eliteness in this dataset. One can also argue about the construction of Positivity with ‘forgave’ in example 6 as well as both Negativity/Positivity in example 5 through Makki 447 Figure 2. Examples of Eliteness in the corpus. ‘martyred’. This is an interesting case and will be discussed further in the ‘Negativity/ Positivity’section. Impact This news value has also been construed in a large number of crime reports, that is, events which have significant consequences (e.g. large scope) affecting many people (Bednarek, 2015). Local events of crime and misadventure did not construct Impact very commonly as the consequences of the actions of criminals were not typically large. Neither did the lexical items used construct any Impact through assessments of significance. However, reported events from overseas did construct Impact as they covered events of terrorist attacks in the neighbouring countries like Iraq and Syria as well as bombings in other parts of the world. Example 7 presents the construction of Impact (Figure 3). The shooting in the LAX Airport, Los Angeles, USA which has led to the death and injury of eight people, is considered of high Impact. There are other examples of bombings in Iraq and Syria which have caused the death of a large number of people (40 deaths and 10s of injured), where Impact and Superlativeness have been both constructed (see ‘Superlativeness’ section). Negativity/Positivity As discussed earlier, the news value of Negativity is excluded in the analysis as there is a very large number of Negativity instances constructed discursively in each news reports, that is, references to criminals and assessments of their behaviour (e.g. criminals, extorters, murderer, paedophile, ruthless, mercilessly, violently) and points of impact in the reports (bribery, extortion, armed robbery). On the other hand, the news value of Positivity is also 448 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Figure 3. An example of Impact in the corpus. constructed in a large number of Iranian crime reports. Positivity is mainly constructed through the ‘detention’, ‘capture’ and ‘arrest’ of the criminal by the police and generally various positive assessments of the police authorities or the police force in general. Another strand of crime reports construing Positivity focuses on ‘forgiveness’ and ‘mercy’ for the killers/murderers through positive lexical terms and expressions.9 Positivity and focus on detention sometimes take the angle of the news story, and the detention of the criminal has been immediately discussed in the headline/lead nucleus (Figure 4). Example 8, which is taken from the headline/lead nucleus, immediately discusses the ‘capture’ of fake police officers suggesting restabilization of the social order (White, 1997). This is very common, as numbers in Table 3 also showed in the previous section; construction of Positivity is so frequent in the crime reports of both newspapers where the social order seems to have been restored by the detention of the criminal. This seems to ratify Feez et al. (2008) that newsworthiness is in essence about reporting both destabilizing (negative) and stabilizing (positive) events. In addition to this restoration of order, almost always by the police force, other Positivity instances were construed through positive assessments of the police and their actions, like examples 9 and 10, that is, police officers have been deemed ‘cognizant’ or ‘dominance and power of police’ or even indirect positive assessment of the police, ‘the detention only took 19 hours’ in example 10 (Martin and White, 2005). Example 11, however, mainly discusses the forgiveness of the killer by the family members of the victim and hence takes a positive angle towards the story, that is, focus is on the forgiveness rather than the crime, and this has been constructed via positive terms such as ‘forgiveness’ and ‘respect for Muharram’. Personalization This news value is mainly about ‘giving a human face to the news through references to ordinary people, their emotions, views, and experiences’ (Bednarek and Caple, 2017: 61). In the corpus of Iranian crime reports, while there are some examples in which an ordinary pedestrian or an eyewitness is reporting on a crime they have observed, the majority of Personalization instances were construed in the description of the criminal’s or the victim’s age, appearance and sometimes occupation. When ‘ordinary citizens are described as engaging in criminal behavior’, the news item can be coded as Personalization (Bednarek, 2015: 11). In such examples, the criminal’s emotions and feelings might have been described (Figure 5). Makki 449 Figure 4. Examples of Positivity in the corpus. The examples above all construe Personalization, 12 and 13 for the murderer and 14 for the victim. In example 12, it is obvious that the individual is named and the report has also refrained from using negative terms such as ‘killer’, ‘husband killer’ or even ‘the woman’. One reason for this can be the sensitive nature of the news story; as Farzane has been the subject of violence and harassment by her husband, she decided to kill her husband herself. Based on the law, the retribution for such crimes in Iran is death by hanging; however, construing Personalization by naming Farzane in the headline and in the story might want to give a human face to the killer in the story, Farzane, suggesting that many other women and potential readers in the country might be the subjects of violence and harassment in their homes. Example 13, more or less, has also intended to give a human face to the individual [criminal] with describing his name and age (obviously very young) and the use of negative Affect, ‘I did not want to kill anyone’, showing remorse on the part of the killer (Martin and White, 2005). Example 14, on the other hand, has constructed Personalization by naming the victim and providing his age (a child in fact). Etemaad Kayhan Eliteness 107 148 Consonance 12 11 22 10 Impact 44 98 Positivity 58 51 Personalization 69 109 Proximity Table 3. Normalized frequency of each instance of constructed news values in local events. 20 53 Superlativeness 79 90 Timeliness 3 1 Unexpectedness 450 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Makki 451 Figure 5. Examples of Personalization in the corpus. Proximity Proximity is conceptualized as concerning the construction of an event as happening ‘geographically’ or ‘culturally’ near the target audience (Bednarek and Caple, 2017). However, defining target audience and who they are can be problematic especially for events covered in a national newspaper with such a wide coverage and audience. So, as discussed earlier, every Iranian city named in the reports can construct Proximity because readers from that city would feel more geographically proximate to the event. There are also reports from criminals who had been stealing in different cities and therefore are proximate with a larger number of readers. Also, given the fact that the newspapers are both published in Tehran (the capital of Iran with a population of around 15,000,000), there is more coverage of events from the capital and Proximity will always be construed by the coverage of events in this city (Figure 6). The examples above all construct Proximity for some specific target audience, two of them geographically and one culturally. Example 15 explains the detention of thieves who were perpetrating in five large provinces, and hence people from those provinces will feel proximate to them. Example 16, though, constructs Proximity for the inhabitants of a large and busy suburb in Tehran. Example 17, with reference to a cultural aspect, ‘Shogam’, discusses a form of illegal murder retaliation, which is known to the people of a southeast province in Iran. So, these examples also appear to corroborate the nature of proximity and how it is better defined on a cline, more near or less near (Bednarek and Caple, 2017: 63). Superlativeness The news value of Superlativeness has been mainly construed through ‘quantifiers’ in the Iranian crime reports, both local and overseas. However, it seems that the threshold level for overseas events is larger than that of local events. For example, if 10 victims 452 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Figure 6. Examples of Proximity in the corpus. have construed Superlativeness for a local event, that number seems to be 20 or more for overseas events, and especially in the events of terrorist attack, for instance. There are also cases of ‘comparisons’ and ‘intensifiers’ in which Superlativeness has been constructed (Figure 7). In examples 18 and 19, Superlativeness has been construed through large numbers and this is the most common type of constructing this news value in the whole dataset; ‘39 martyrs and 25 injured’, in example 19, as also noted before, construes Impact as well. This is a clear example of the co-occurrence of both Impact and Superlativeness in the Iranian sample, just like what can be observed in English language publications (see Bednarek and Caple, 2017: 60). Intensifiers, ‘significant amount of’ and comparisons, ‘more than …’ in examples 20 and 21 are the next recurring linguistic resources for the construction of Superlativeness in the crime reports. Timeliness This news value is generally constructed via the present and present tense of the verbs, and the application of lexical time references, both suggesting currency and urgency of the event (Bednarek, 2016). In the Iranian corpus, there is another linguistic device and that is the use of direct and indirect ‘imperatives’ with Observed Affect (White, 2012), non-authorial affect, by police officers in order to warn the public about a perpetrator Makki 453 Figure 7. Examples of Superlativeness in the corpus. on the loose or encourage them to go to the police and file a report about a perpetrator who seems to have preyed more victims than what is assumed (Figure 8). In example 22, the present perfect tense (have not been detained) and the lexical item (yet) construct Timeliness and the ongoing nature of the event. Examples 23 and 24 are actually in the police’s voice, and not only the present tense construes Timeliness of the event but also the direct or indirect imperatives of the police officer construct this news value, that is, ‘it is recommended’, ‘plaintiffs … are invited to attend …’. These reports are very common in the Iranian corpus, and the lexical terms such as ‘invite’, ‘ask’, ‘encourage’, which are requests made almost always by an elite police officer, suggest Observed Affect from police authorities and function to construct Timeliness via the lexical items and the imperative mode. Unexpectedness This news value was constructed discursively in a few instances in the corpus. In local events, it was construed where there were assessments of police’s actions and in overseas events, through unusual happenings and events. Before providing examples, a few caveats about Unexpectedness in the crime events should be noted: first is the exclusion of events such as ‘father killing son’ and ‘a taxi driver killing a 6-year old’, which can be so unusual 454 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Figure 8. Examples of Timeliness in the corpus. due to the murder of a close family member or a child. However, then, most reports can be taken to construe Unexpectedness as they mostly involve murder. So, the unusual events counted and analysed in this study are mostly feel-good and ‘fancy-that’ stories in which a person has been saved (Gillman, 2011). The other caveat in point is the stories about ‘forgiveness’ and ‘mercy’ for the killer/murder from the avengers of blood, close family members (see Note 9). These stories were not considered as Unexpectedness as it is not clear whether forgiveness is rare in the Iranian culture to be considered unexpected. Instead, they are deemed to construct Positivity discursively in the reports, as discussed earlier (Figure 9). Example 25 provides an evaluation of unexpectedness, ‘surprising’, which is attributed to the police force. There are a few other such assessments in the crime reports, that is, ‘suddenly’ and ‘unexpectedly’. The other example, 26, refers to an unusual happening which has ended well. In fact, both ‘burying somebody alive and that person saving herself’ in the 21st century is an unexpected event which can construe Unexpectedness for the target audience. Concluding remarks This article analysed how news values are discursively constructed in a corpus of Iranian/ Farsi language crime news reports, with Negativity being the prerequisite for the data sample. While the frequency of each news value in the corpus data was normalized Makki 455 Figure 9. Examples of Unexpectedness in the corpus. (Tables 3 and 4), as the corpora were of different sizes, the main focus of the article was on providing how each news value was constructed linguistically. Eliteness was the most commonly constructed news value and Unexpectedness was the least commonly constructed one in the newspapers. This article, like earlier studies, found that Proximity should be conceptualized on a cline as places can be considered only more or less near the target audience (Bednarek, 2015; Bednarek and Caple, 2017). In addition, the sociocultural Iranian context seems to have influenced the linguistic choices made by the newspapers. It was shown to have influenced the widespread presence of police authorities, which generally directed the angle of the news story towards the ‘restoration of the order’ or ‘stabilizing the order’ or ‘solved crime’ (Chibnall, 1977; Feez et al., 2008). In such reports, lexical items such as ‘detention’, ‘capture’, ‘bringing back to justice’, with positive assessments of police officers and their behaviours, can be seen to construe the news value of Positivity so frequently, being untypical of a crime news report. This is even more obvious in the more religious, pro-Sharia newspaper, Kayhan, which is, following the Iranian Supreme Leader, inclined to cover positive and hopeful news (Muchtar et al., 2017). Also, the Iranian journalism context has constructed a few news values differently from what is normally perceived in the literature (Bednarek, 2016; Bednarek and Caple, 2017). The use of the lexical item ‘martyred’ instead of ‘killed’ for the police force, an ideologically positive term for an Iranian Shiite audience, was an example. Another recurring instance was the ‘forgiveness’ or ‘mercy’ of family members of the victim towards the killer, leading to the construction of Positivity in the Iranian crime reports. There was also another socioculturally distinctive element in the data, that is, construction of Timeliness through the use of direct or indirect imperatives by a police authority of high rank, suggesting the ongoing nature of the risk for the society. This article made an effort to provide a ‘snapshot’ of DNVA in a corpus of Iranian/ Farsi language crime reports. More research is required into the linguistic properties of news values in the Iranian context and in crime reports in general. Analysis of other semiotic modes such as ‘photos’ or ‘visual imagery’ alongside the linguistic analysis can Etemaad Kayhan Eliteness 236 186 Consonance 21 28 21 10 Impact 12 80 Positivity 43 109 Personalization 223 147 Proximity Table 4. Normalized frequency of each instance of constructed news values in overseas events. 47 22 Superlativeness 193 77 Timeliness 0 16 Unexpectedness 456 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Makki 457 provide useful insights into the journalism of other non-English contexts and cultures (Dahl and Fløttum, 2017). Ideally, access to newsrooms and staff meetings and to the underlying selection process of news reports will shed more light to the working of news production (Huan, 2016). Last but not least, close attention to the role of sociopolitical authorities and supervisory systems can provide a more comprehensive overview of the news journalism practice. Acknowledgements I wish to express my gratitude to Dr Helen Caple for her careful edits and comments on the early draft of this paper. I would like to thank Associate Professor Monika Bednarek to answer all my questions on the analysis of data patiently. Many thanks to Dr Peter RR White for his supervision of my PhD, to which this paper is also related. I am solely responsible for any errors. Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. All news values in discursive news values analysis’ (DNVA) terms have initial capital letters. They might be used in the general meaning of the word without any specific capitalization: Negativity versus negativity. The terms ‘construct’ and ‘construe’ are used interchangeably in this article and refer to the linguistic aspect of news values (Bednarek and Caple, 2017: 49). Attitudinal language is concerned with emotional reactions [affect], evaluations of human behaviour via social and ethical norms [Judgement] and assessment of things and actions [appreciation]. For some important resources on Appraisal and Attitudinal language, see Martin (2000), Martin and White (2005) and Bednarek (2006). Persian/Farsi is a right to left language, and UAM Corpus cannot handle these languages yet as the fonts will be distorted. The parts which construct the news value have been underlined. An Iranian city lying on the border with Afghanistan. This is a month, which is very sacred for the Shiite due to the martyrdom of Imam Hussein (third Imam of the Shiites). The 9th and 10th days of the Muharram in which Imam Hussein was martyred and the Shiite still mourn and observe these events in such dates. Based on the law, if somebody kills another person, there is capital punishment unless the avengers of blood (father, mother, son, etc.) forgive the killer. References Bahrampour S (2004) The necessity of revising the media and press policymaking. Rasaneh (The Media) 15(2): 61–76 (in Persian/Farsi). 458 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Bednarek M (2006) Evaluation in Media Discourse. London: Continuum. Bednarek M (2015) Coding manual for linguistic analysis. Available at: www.newsvaluesanaly sis.com Bednarek M (2016) Investigating evaluation and news values in news items that are shared through social media. Corpora 11: 227–257. Bednarek M and Caple H (2012) News Discourse. London; New York: Continuum. Bednarek M and Caple H (2014) Why do news values matter? Towards a new methodological framework for analysing news discourse in critical discourse analysis and beyond. Discourse & Society 25: 135–158. Bednarek M and Caple H (2017) The Discourse of News Values: How News Organizations Create Newsworthiness. New York: Oxford University Press. Behnam B and Zenouz RM (2008) A contrastive critical analysis of Iranian and British newspaper reports on the Iran nuclear power program. In: Nørgaard N (ed.) Systemic Functional Linguistics in Use (Odense Working Papers in Language and Communication). Odense: University of Southern Denmark, pp. 199–218. Bell A (1991) The Language of News Media. Oxford: Blackwell. Caple H (2018) News values and newsworthiness. In: Ornebring H (ed.) Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore /9780190228613.013.850 Caple H and Bednarek M (2013) Delving into the discourse: Approaches to news values in journalism studies and beyond. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default /files/2018-01/Delving%20into%20the%20Discourse.pdff Caple H and Bednarek M (2016) Rethinking news values: What a discursive approach can tell us about the construction of news discourse and news photography. Journalism 17: 435–455. Catalano T (2014) The Roma and Wall Street/CEOs: Linguistic construction of identity in US and Canadian crime reports. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 38: 133–156. Chermak S and Chapman NM (2007) Predicting crime story salience: A replication. Journal of Criminal Justice 35(4): 351–363. Chibnall S (1977) Law-and-order News: An Analysis of Crime Reporting in the British Press. Abingdon: Tavistock Publications. Cohen S (1972) Moral Panics and Folk Devils. London: MacGibbon and Kee. Conboy M (2004) Journalism: A Critical History. London: SAGE. Cotter C (2010) News Talk: Investigating the Language of Journalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dahl T and Fløttum K (2017) Verbal–visual harmony or dissonance? A news values analysis of multimodal news texts on climate change. Discourse, Context and Media 20: 124–131. Faris DM and Rahimi B (2015) Social Media in Iran: Politics and Society after 2009. New York: SUNY Press. Feez S, Iedema R and White P (2008) Media Literacy. Sydney, NSW, Australia: NSW Adult Migrant Education Service. Fowler R (1991) Language in the News: Discourse and Ideology in the Press. London: Routledge. Fruttaldo A and Venuti M (2017) A Cross-cultural discursive approach to news values in the press in the US, the UK and Italy: The case of the Supreme Court ruling on same sex marriage. ESP Across Cultures 14: 42–57. Galtung J and Ruge M (1965) The structure of foreign news: The representation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research 2: 64–90. Gillman S (2011) News values and news culture in a changing world. In: Bainbridge J, Goc N and Tynan E (eds) Media and Journalism: New Approaches to Theory and Practice. London: Oxford University Press, pp. 245–256. Makki 459 Good M-JD and Good BJ (1988) Ritual, the state, and the transformation of emotional discourse in Iranian society. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 12: 43–63. Hall S, Clarke J and Critcher C (1978) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, Law and Order and the State. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Harcup T and O’Neill D (2017) What is news? News values revisited (again). Journalism Studies 18: 1470–1488. Huan C (2016) Leaders or readers, whom to please? News values in the transition of the Chinese press. Discourse, Context and Media 13: 114–121. Innes M (1999) The media as an investigative resource in murder enquiries. British Journal of Criminology 39: 269–286. Iranian Students’ News Agency (ISNA) (1999) Send good, positive and hopeful news. Available at: http://alborz.isna.ir/Default.aspx?NSID=5andSSLID=46andNID=9446 (accessed 25 January 2019) (in Persian). Izadi F and Saghaye-Biria H (2007) A discourse analysis of elite American newspaper editorials: The case of Iran’s nuclear program. Journal of Communication Inquiry 31: 140–165. Khiabany G (2010) Iranian Media: The Paradox of Modernity. London: Routledge. Khosravinik M (2015) Discourse, Identity and Legitimacy: Self and Other in Representations of Iran's Nuclear Programme. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Koosha M and Shams MR (2005) A critical study of news discourse: Iran’s nuclear issue in the British newspapers. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics 8: 101–141. McEnery T, Xiao R and Tono Y (2006) Corpus-based Language Studies: An Advanced Resource Book. London: Taylor and Francis. Machin M and Mayr A (2012) How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: SAGE. Makki M and White PRR (2018) Socio-cultural conditioning of style and structure in journalistic discourse: The distinctively ‘objective’ textuality of Iranian political news reporting. Discourse, Context and Media 21: 54–63. Martin JR (2000) Beyond exchange: Appraisal systems in English. In: Hunston S and Thompson G (eds) Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse. London: Oxford University Press, pp. 142–175. Martin JR and White PRR (2005) The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Mindich DTZ (1998) Just the Facts: How Objectivity Came to Define American Journalism. New York: New York University Press. Molek-Kozakowska K (2017) Communicating environmental science beyond academia: Stylistic patterns of newsworthiness in popular science journalism. Discourse & Communication 11: 69–88. Muchtar N, Hamada BI, Hanitzsch T, et al. (2017) Journalism and the Islamic worldview: Journalistic roles in Muslim-majority countries. Journalism Studies 18(5): 555–575. O’Donnell M (2015) UAM Corpus Tool. Available at: http://www.corpustool.com O’Neill D and Harcup T (2009) News values and selectivity. In: Wahl-Jorgensen K and Hanitzsch T (eds) The Handbook of Journalism Studies. New York: Routledge, pp. 181–194. Parks P (2018) Naturalizing negativity: How journalism textbooks justify crime, conflict, and ‘bad’ news. Critical Studies in Media Communication 36(1): 75–91. Rafiee A, Spooren W and Sanders J (2018) Culture and discourse structure: A comparative study of Dutch and Iranian news texts. Discourse & Communication 12: 58–79. Rasti A and Sahragard R (2012) Actor analysis and action delegitimation of the participants involved in Iran’s nuclear power contention: A case study of The Economist. Discourse & Society 23: 729–748. 460 Discourse & Communication 13(4) Reiner R (2007) Media-made criminality: The representation of crime in the mass media. In: Maguire M, Morgan R and Reiner R (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, 4th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 302–327. Reiner R (2010) The Politics of the Police. London: Oxford University Press. Richardson JE (2007) Analysing Newspapers: An Approach from Critical Discourse Analysis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Schlesinger P and Tumber H (1994) Reporting Crime: The Media Politics of Criminal Justice. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Schultz I (2007) The journalistic gut feeling: Journalistic doxa, news habitus and orthodox news values. Journalism Practice 1: 190–207. Semati M (2008) Media, Culture, Society in Iran: Living with Globalisation and the Islamic State. London: Routledge. Shahidi H (2007) Journalism in Iran: From Mission to Profession. London: Routledge. Steele J (2013) ‘Trial by the press’: An examination of journalism, ethics, and Islam in Indonesia and Malaysia. The International Journal of Press/Politics 18: 342–359. Van Dijk TA (1988) News as Discourse. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Van Dijk TA (1998) Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. London: SAGE. White PRR (1997) Death, disruption and the moral order: The narrative impulse in mass-media ‘hard news’ reporting. In: Christie F and Martin JR (eds) Genres and Institution: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. London: Cassell, pp. 101–133. White PRR (2012) Exploring the axiological workings of ‘reporter voice’ news stories – Attribution and attitudinal positioning. Discourse, Context and Media 1: 57–67. White PRR and Makki M (2016) Crime reporting as storytelling in Persian/Farsi news journalism – Perspectives on the narrative function. Journal of World Languages 3: 117–138. Young J (1971) The role of the police as amplifiers of deviancy, negotiators of reality and translators of fantasy. Images of Deviance 37: 27–61. Author biography Mohammad Makki received his PhD in Media from University of New South Wales, Sydney, in 2016. He is generally interested in analysing the discourse of media with reference to the ideological working of the society. He has worked on the discourse of Iranian Farsi language newspapers with attention to news values, journalistic genres and writing styles. He has published two papers from his PhD in Discourse, Context, & Media and Journal of World Languages. He teaches undergraduate and postgraduate subjects in media, linguistics and discourse analysis, as well as Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) in University of New South Wales and University of Wollongong.