Philippines MDG Progress: Poverty, Education, Gender Equality

advertisement

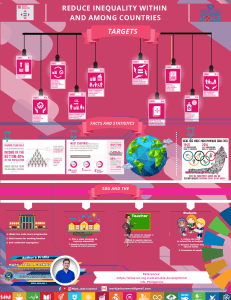

Available data on Goal 1 (Eradication of Income Poverty and Hunger) indicate huge potential in reducing the poverty gap and in halving the prevalence of hunger. At the same time, the chances of halving the incidence of income poverty and underweight children under 5 years of age are uncertain. The current assessment system does not also provide similar estimates on the probability of achieving the targets related to employment. The targets are to halve, between 1990 and 2015, (a) the proportion of the population whose income is less than one US dollar a day (now adjusted to one US dollar and twenty-five cents), and (b) the proportion who suffer from hunger. Since 2008, a third target was added, i.e., to achieve a full and productive employment and decent work for all, including women and young people. These targets are supported by nine indicators linked to progress monitoring. The four indicators used by the Government to track efforts pertaining to poverty and hunger are: (1) proportion of population with income below the official poverty threshold; (2) the proportion of population with income below the official food threshold (also referred to as subsistence threshold); (3) prevalence of underweight children under 5 years of age; and (4) proportion of households with per capita intake below 100 percent dietary energy requirement. Based on official data as reported by Balisacan (NAST, 2010), the country is broadly on its way to achieving MDG 1 despite the increase of poverty in 2006. The probability of halving the proportion of the population whose incomes are below the official poverty lines, between 1991 and 2015, is medium or average. So are the two indicators of hunger. The chance of achieving the target is high for the proportion of the population whose incomes are below the food threshold. In February 2011, the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) reported a refinement in the methodology for estimating poverty as of 2009. The refined methodology did not change the definition of poverty but was meant to better measure the poor and to ensure comparability over space and time. The chance of halving poverty between 1990 and 2015 using the 2009 poverty estimates, declined but remains at medium. https://nast.dost.gov.ph/images/pdf%20files/Publications/Bulletins/NB%202%20MDG%20Updat es.pdf OBJECTIVES The 4Ps has dual objectives as the flagship poverty alleviation program of the Aquino administration: 1. social assistance, giving monetary support to extremely poor families to respond to their immediate needs; and 2. social development, breaking the intergenerational poverty cycle by investing in the health and education of poor children through programs such as: o health check-ups for pregnant women and children aged 0 to 5; o deworming of schoolchildren aged 6 to 14; o enrollment of children in daycare, elementary, and secondary schools; and o family development sessions. The Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) is a human development measure of the national government that provides conditional cash grants to the poorest of the poor, to improve the health, nutrition, and the education of children aged 0-18. It is patterned after the conditional cash transfer (CCT) schemes in Latin American and African countries, which have lifted millions of people around the world from poverty. The 4Ps also helps the Philippine government fulfill its commitment to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)—specifically in eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, in achieving universal primary education, in promoting gender equality, in reducing child mortality, and in improving maternal health care. CASH GRANTS The 4Ps has two types of cash grants that are given out to household-beneficiaries: health grant: P500 per household every month, or a total of P6,000 every year education grant: P300 per child every month for ten months, or a total of P3,000 every year (a household may register a maximum of three children for the program) PARTNERSHIPS WITH GOVERNMENT AGENCIES In partnership with the Commission on Higher Education, the Department of Labor and Employment, and the Philippine Association of State Universities and Colleges, 4Ps has enrolled 36,003 beneficiaries in state universities and colleges as of June 2015. Additionally, in partnership with PhilHealth, 4Ps has covered 4.4 million beneficiaries under the National Health Insurance Program. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/programs/conditional-cashtransfer/?fbclid=IwAR3zXvKcXnnu8BY2CKfoQ_hlsoiTSFWtfYUScj7g1tvg6HL8ev-JpmFZLdY IFPRI, 2002. Green Revolution: Curse or Blessing? Available: http://www.ifpri.org/pubs/ib/ib11.pdf The possibility of reaching Goal 2 (Achievement of Universal Primary Education) by 2015 is challenged by low probabilities of achieving the targets on cohort survival and completion rates in primary education, and literacy rates of those between 15 to 24 years of age. While government education programmes have intensified through the years, the underlying problems of poverty, peace and order, and health have been identified as exacerbating the need to meet an ever-increasing demand for facilities and educators. The Philippines 2010 Progress Report on Millennium Development Goals (MDG) has identified the IMPACT Learning System as an effective way for attaining universal primary education. The Report states that the rate of achievement of MDG Goal 2 is considerably low but a case study of the IMPACT Learning System as reported by the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) reveals its benefit in ensuring access to and quality of primary education for all children. The Report shares that studies have proven how the IMPACT Learning System “consistently demonstrated cost-efficiency (reducing the cost of elementary education by up to 50 percent without sacrificing quality) and has positively contributed to the improvement of instructional quality and pupils’ academic performance.” The Instructional Management by Parents, Community and Teachers (IMPACT) system is an alternative learning delivery mode for basic education developed by SEAMEO INNOTECH more than three decades ago, in cooperation with the then Department of Education and Culture, and with funding support from the International Development Research Center (IDRC) of Canada. The system initially intended to address overcrowding in Philippine public schools and the lack of teachers and learning materials. Its most salient feature is the active participation of the parents, the school teachers and officials, and the community leaders in the learning process of the children. https://www.seameo-innotech.org/philippines-2010-mdg-progress-report-cites-impact-learningsystem/?fbclid=IwAR0iqJwOBAYIYpIJWod_iLwnkomoPTfhcDR1GUg4SORxTkqd0ESdjySvS7I# However, against the backdrop of existing policies and programs, it may be possible to come very close to the goal, if not realize it by 2015, provided that the DepEd implements vigorously the Basic Education Reform Agenda (BESRA). The potential of BESRA rests on School-Based Management (SBM) which enables schooland community-level stakeholders to use their empowerment to chart the course and means of their progress towards achieving better education outcomes. Unless BESRA is seen as the most promising guide to quality basic education, a potentially meaningful reform mission that could enable the Philippines to meet the MDG commitments will merely be perceived as burdensome work. https://nast.dost.gov.ph/images/pdf%20files/Publications/Bulletins/NB%202%20MDG%20Updates.pdf The Philippines will most likely report success in achieving Goal 3 (Promotion of Gender Equality and Women‘s Empowerment), as indicated by gender parity in elementary and secondary education, and also in terms of the share of women in wage employment in the non-agricultural sector. There did not seem much of a gender gap in education since baseline [Table 1], which shows that the country had been innately better-off than other nations where this has been a challenge. Based on the 2013 data, The Philippines will most likely report success in achieving Goal 3 (Promotion of Gender Equality and Women‘s Empowerment), as indicated by gender parity in elementary and secondary education, and also in terms of the share of women in wage employment in the nonagricultural sector. http://www.mdgfund.org/sites/default/files/Philippines_Country%20Final%20Evaluation.pdf page 15 Since the introduction of gender mainstreaming through Republic Act 7192 or the Women in Development and Nation Building Act and its institutionalization in Republic Act 9710 or the Magna Carta of Women (MCW) in 2009, the Philippines has sustained the integration of gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE) concerns in government policies and programs. Through the concerted efforts of government and civil society through the women’s movement, major strides have been taken towards achieving gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in the country. The Philippines’ rank among the top ten countries in the Global Gender Gap Index is an evidence of the country’s significant gains in reducing gender disparities. The Philippines maintained its position since 2006, as one of the most gender equal countries in the world, and the top placer in Southeast Asia. https://www.bfar.da.gov.ph/wpcontent/uploads/2021/12/ME_of_GEWEVol1.pdf page 5 The National Competitiveness Council is pleased to report that the Philippines remains to be the top country in the ASEAN region in terms of gender equality, retaining 7th place out of 144 countries in the 2016 Global Gender Gap Report published by the World Economic Forum. http://www.competitive.org.ph/stories/1323#:~:text=The%20National%20Competitiveness%20Council% 20is,by%20the%20World%20Economic%20Forum. However, work still needs to be done in the Philippines to achieve gender equality. 66.7% of legal frameworks that promote, enforce and monitor gender equality under the SDG indicator, with a focus on violence against women, are in place. In 2018, 5.9% of women aged 15-49 years reported that they had been subject to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months. Moreover, women of reproductive age (15-49 years) often face barriers with respect to their sexual and reproductive health and rights: in 2017, 56% of women had their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods. https://data.unwomen.org/country/philippines CHAPTER 5 EDUCATION The COVID-19 pandemic created the largest disruption of education systems in history, affecting nearly 1.6 billion learners in more than 190 countries and all continents. 94 Preventing a learning crisis from becoming a generational catastrophe requires urgent action from all as education is not only a fundamental human right. It is an enabling right with direct impact on the realization of all other human rights, particularly for the poor and marginalized and those who experience multiple layers of discrimination, such as women and girls. It is a primary driver of progress across all Sustainable Development Goals and a bedrock of just, equal, inclusive peaceful societies. 95 Education is a sector where the Philippines achieved gender equality targets in the Millennium Development Goals, having achieved universal access to primary education for girls and boys, with even higher literacy rate for girls than boys in both basic and functional literacy. However, while the total female literacy rate in the Philippines has remained at 98.20 percent for 2019-2020, gender analysts highlight that even before the crisis, nearly 63 percent of the young children who dropped out of school in the Philippines were girls.96 Similar to global trends for middle income countries, the economic impact of COVID-19 threatens many poor families’ ability to afford sending their children – boys and girls- to school, with potential pressure on families to rely on young girls to help with the increased unpaid care work. https://itdi.dost.gov.ph/images/GAD/UpdatedPlan20192025.pdf The country’s probable feat in achieving Goal 4 (Reduction of Child Mortality) has been attributed to the effectiveness of government interventions on the improvement of maternal care and child health. These include programmes on breastfeeding, micronutrient supplementation, and immunization of both children and mothers. It has also been earlier asserted [NDHS, 1998] that maternal education and access to antenatal care or medical assistance at the time of delivery are associated with child mortality in the country, suggesting that improvements on these areas could have likewise been occurring over time. 2 Significant reduction in child mortality has been made due to intensified government programs on health, and the adoption of the life cycle approach in ensuring continuum of care. (eg. received the measles vaccine by 12 months of age. Less than six of 10 mothers (57.6 percent) could show a vaccination card to the interviewer which accounts for the far from complete immunization of infants against measles.) The Department of Health (DOH) strategies for achieving MDG 4 include: skilled birth attendance; essential newborn care; integrated management of sick children; micronutrient supplementation; immunization; breastfeeding; and birth spacing. According to the 2013 NDHS data, the goal of reducing the under-five mortality rate to a level of 26.7 deaths per 1,000 live births is likely to be achieved in 2015. The goal for reducing the IMR to 19 infant deaths per 1,000 live births is also achievable by 2015 https://www.philstar.com/business/science-andenvironment/2014/05/29/1328329/philippine-scorecard-mdgs-4-and-5 Goal 5 (Improvement of Maternal Health) has also been a perennial challenge in the Philippines. Maternal mortality remained high, while the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel and the contraceptive prevalence were still below targets as of latest estimates. These have been assessed with low probabilities of achievement at the current period. It was reported that interventions on these have been affected by geographical barriers between the poor and the health facilities in remote areas, financial constraints by the income poor in delivering out-of-pocket costs, and their limited information on health risks. The Philippines failed to achieve its Millennium Development Goal (MDG) commitment to reduce maternal deaths by three quarters. This, together with the recently launched Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), reinforces the need for the country to keep up in improving reach of maternal and child health (MCH) services. Inequitable use of health services is a risk factor for the differences in health outcomes across socio-economic groups. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5105289/ One of these is the goal to reduce maternal deaths by three quarters between 1990 and 2015 (Millennium Development Goals). While the overall improvements in maternal health globally had been remarkable, the poor and the vulnerable were unfortunately left behind [1 1. United Nations . The millenium development goals report. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) ended in 2015, but disparities in access to (and use of) maternal health services may still be observed in many countries. Post-MDGs, further reduction of maternal deaths remain in the recently launched Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Reducing the global mortality ratio to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births requires countries like the Philippines to scale-up efforts to effectively improve maternal and child health conditions. Evidence suggest improving Maternal and Child Health (MCH) services has an effect not only on the reduction of maternal deaths but extends to also impact reduction in neonatal and post neonatal mortality rates [2 1. United Nations . The millenium development goals report. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar] ]. In absolute figures, women who delivered in facilities increased from 2008 to 2013. Little change was noted for women who received complete antenatal care and caesarean births. Facility deliveries remain pro-rich although a pro-poor shift was noted. Women who received complete antenatal care services also remain concentrated to the rich. Further, there is a highly pro-rich inequality in caesarean deliveries which did not change much from 2008 to 2013. Household income remains as the most important contributor to the resulting inequalities in health services use, followed by maternal education. For complete antenatal care use and deliveries in government facilities, regional differences also showed to have important contribution. The findings suggest inequality in the use of MCH services had limited pro-poor improvements. Household income remains to be the major driver of inequities in MCH services use in the Philippines. This is despite the recent national government-led subsidy for the health insurance of the poor. The highly prorich caesarean deliveries may also warrant the need for future studies to determine the prevalence of medically unindicated caesarean births among high-income women. In 2011, a Universal Health Care (UHC) strategy was launched in the Philippines [5 5. Kalusugan Pangkalahatan Execution Plan and Implementation Arrangements, 2011]. In the strategy, attention was given to improving the overall health system and in protecting the poor from financial risks. A national government-led subsidy for the health insurance of the poor was not only seen as a means to increase healthcare utilization but also to ensure placement of sustainable healthcare financing [6 6. Silfverberg R. The sponsored program of the Philippine National Health Insurance - analyses of the actual coverage and variations across regions and provinces Makati City, Philippines2014 Available from: http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/webportal/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1419.pdf, 7 7. Chakraborty S. Philippines’ Government Sponsored Health Coverage Program for the Poor Households Washington DC: The World Bank; 2013 Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/13295/75010.pdf?sequence=1]. The maternal and child health strategy in the Philippines was also aligned with the launched UHC program – bringing the need to reduce unmet needs in family planning, facility-based deliveries and others in the national priority. Many other reforms followed in the Philippines that is also expected to benefit the MCH situation. This includes the historical passing of a reproductive health law which aims to ensure government support to maternal and child health programs, together with the provision of modern contraceptives in government facilities [8 8. An act providing for a national policy on responsible parenthood and reproductive health, 2012]. Furthermore, the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) program in the country also includes conditions specific for maternal health. All women beneficiary of the cash transfer program is required to complete at least 4 antenatal care visits and deliver in a facility should they become pregnant [9 9. Fernandez L, Olfindo R. Overview of the Philippines’ conditional cash transfer program: the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (Pantawid Pamilya). Philippine Social Protection Note. 2011;No. 2]. While progress has been encouraging in the past decade, many other strategies are still needed to ensure protection of every pregnancy and children born in the country [10 10. National Economic Development Authority & United Nations Development Programme. The Philippines: Fifth Progress Report - Millenium Development Goals Philippines: National Economic and Development Authority; 2014 Available from: http://www.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MDG-Progress-Report-5-Final.pdf]. Most of the indicators associated with the achievement of Goal 6 (Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria and Other Diseases) were also assessed to be highly achievable. The only problems seemed to be those related to tuberculosis. The achievement of Goal 7 (Ensuring Environmental Sustainability) and Goal 8 (Development of a Global Partnership for Development) is made uncertain by the lack of probability estimates on most of the indicators associated with these. Nonetheless, the GPH reported high probabilities in achieving the targets on the proportion of families with access to safe water and sanitary toilet facilities. According to the Philippine government’s reporting, the country will have high probability of achieving the targets on food poverty (MDG 1), gender equality in education (MDG 3), reducing child mortality (MDG 4), combating malaria and tuberculosis (MDG 6), and improving access to sanitary toilet facilities (MDG 7) by 2015.21 There is medium probability of meeting the following targets: income poverty, nutrition, and dietary energy requirement (MDG 1), and access to safe drinking water (MDG 7). However, there is low probability in meeting the targets for elementary participation, survival and completion rates (MDG 2), maternal mortality ratio and access to reproductive health services (MDG 5), and HIV/AIDS (MDG 6). Factors Affecting the Progress of Achieving the MDGs and Recommendations to Further Advance the Implementation of MDGs in the Philippines (https://cdn.fbsbx.com/v/t59.270821/396457706_975603073536807_6222644569115191784_n.pdf/09-JICAVol2Chapter4Atienza2012.pdf?_nc_cat=107&ccb=17&_nc_sid=2b0e22&_nc_ohc=JRYKxbL4CYMAX8Ob36s&_nc_oc=AQngSXCq6m5i6ZivgzCiQ7iYSGxx92EQ3 onTGnujFrDXJgrqxwUNJQWDsj7DR5_JRAjmSQrPpkPNOBIxFsPGc18&_nc_ht=cdn.fbsbx.com&oh=03_AdSZq0FusClIwEDPy_hqc9VfpyvxSH30spKCgKrHN8zxA&oe=65420E11&dl=1) The factors resulting in the uneven progress can be grouped into two: financial and governance factors. The financial factors include the country’s weakening fiscal situation and automatic debt servicing. These reduced total expenditures, especially for social and economic services that support the attainment of the MDGs. According to Lim, in 2005 the debt servicing for interest and principal payments comprised more than 85% of government revenues.45 Manasan noted in 2008 that real per capita national government spending on MDG interventions (in 2000 prices) decreased from PhP 1,997 in 1997 to PhP 1,344 in 2005 before posting a partial recovery to PhP 1,581 in 2006.46 In addition, real per capita national government spending on basic social services went down from PhP 1,482 in 1997 to PhP 1,056 in 2005 before climbing to PhP 1,124 in 2006. The cut in real per capita national government spending was deepest in basic water and sanitation (29% yearly on average between 1997 and 2005), followed by basic health and nutrition (11%) and pro-poor infrastructure (10%). Manasan projected in 2007 that the cumulative resource gap for 2007 to 2010 was going to be PhP 409.5 billion (or 1.3% of the GDP) under the MTPDP GDP growth rate assumption.47 Governance factors, meanwhile, are as follows: lack of political stability, less government effectiveness and political will to make sound and progressive policies; poor regulatory quality; weak rule of law; and graft and corruption. The latest reports already recognize sustained economic growth as a way of moving forward.49 This, however, requires sustained reforms in the area of governance, particularly better population management, greater focus on underserved areas, adequate safety nets, improved targeting, improved governance and transparency, improved peace and security, greater advocacy and localization, and strengthen publicprivate partnerships.50 The Philippine Development Forum supplemented these observations with recommendations for governance reforms in different sectors Issues to meet the 2015 MDGs Address wide disparities across regions , Curb the high population growth rate, Improve performance of the agriculture sector, Accelerate the implementation of basic education and health reforms, • Ensure strict enforcement of laws pertinent to the achievement of the MDGs • Bridge the financing gap • Strengthen the capacity of the local government units to deliver basic social services and manage programs and projects • Ensure transparency and accountability in government transactions, Address peace and security issues • Strengthen for public-private partnership • Improve targeting, database and monitoring. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/mdg_workshops/bangkok_training_mdgs/philippines _mdg_overview_bnk.pdf