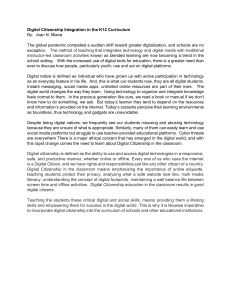

Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy Research & Social Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/erss Original research article Energy platforms and the future of energy citizenship☆ Marten Boekelo, Sanneke Kloppenburg * Wageningen University, Environmental Policy Group, Hollandseweg 1, 6706 KN Wageningen, the Netherlands. A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Energy platforms Energy citizenship Digitalisation Agency Energy communities Energy platforms involve citizens in the energy system by creating and orchestrating virtual energy collectives that can support energy system governance. In such an energy collective, households pool their resources to engage in energy trading, collective self-consumption, or grid balancing. In this paper we draw on the theory of material participation to examine how everyday interactions with energy platform technologies enable people to enact energy citizenship. Our findings from interviews and workshops in a demonstration project of an energy platform show that energy platforms complicate the notion of being an energy citizen. For the householders in our research, engaging in new collective energy practices disturbed the existing link between domestic energy practices and energy citizenship. Where people's energy citizenship used to be centred around their own do­ mestic domain, engagement with platform technologies required them to reflect on their position in relation to new issues such as the ‘greenness’ of various energy markets. Moreover, people were confused about the relation between their own agency and goals as an energy citizen, vis-a-vis the collective agency that results from the bundling of energy practices, and the power and motivations of platform providers and energy system actors. Uncertainties around agency and responsibility need to be reduced if platform-based energy collectives are to play a role in fostering meaningful citizen participation in the energy transition. For platform providers, this implies acknowledging people's existing practices and trajectories of energy citizenship, and providing feedback about the contributions people are making. 1. Introduction A recent development in the decentralisation and digitalisation of the energy system is the emergence of energy platforms. Energy plat­ forms can be defined as digital infrastructures that connect small-scale energy producers and consumers and facilitate transactions between them [15]. By linking domestic devices such as solar panels and home batteries of different households, these digital infrastructures create a common pool of energy that can be managed for purposes such as energy sharing, trading, or providing grid balancing services. For householders, joining an energy platform opens up possibilities to participate in the energy system and its governance in new ways. Together, as a virtual energy collective, they can optimise self-consumption of green energy, or participate in energy and demand response markets. In this article, we understand the energy platform as an energy technology that brings the energy system closer to people's everyday lives, and could provide them with new possibilities to exercise energy citizenship. To conceptualise this, we draw on approaches in the energy social sciences that highlight how energy technologies that are located in or close to people's homes enable participation and engagement in the energy transition [18,30]. Rooftop solar panels and energy monitoring devices, for example, enable people to generate their own green energy and to monitor and manage energy flows at household level. Through everyday interactions with such objects and technologies, people can become aware of new issues, such as the fluctuating availability of green electricity, and adapt their behaviour accordingly (shifting electricity consumption to midday, for example) or make new purchasing decisions (an EV or household battery). In other words, they start to engage actively with the energy transition. Such everyday objects and practices then can be seen as a domain in which people enact their citizenship, as members of the public [18]. This understanding of citizenship, which emphasizes its everyday and physical dimensions, is different from more conventional con­ ceptualisations of citizenship as of political activism, citizen consulta­ tion, or involvement in grassroots initiatives [5]. We adopt this perspective, the so-called theory of material participation [18], because This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research NWO under Grant number 408.URS+.16.004. * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: marten.boekelo@duneworks.nl (M. Boekelo), sanneke.kloppenburg@wur.nl (S. Kloppenburg). ☆ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103165 Received 23 December 2022; Received in revised form 21 April 2023; Accepted 2 June 2023 Available online 19 June 2023 2214-6296/© 2023 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 it is particularly suitable for understanding people's engagement with what has been called ‘the next phase of the energy transition’, in which we witness complex interactions of multiple technologies and sectors [17,42]. In particular, when smart grid technology enters the household and stimulates householders to manage their energy practices in accordance with the needs of the grid, everyday domestic energy con­ sumption practices become rearticulated as a public issue [40]. At the same time, smart grid technology often relies on automation of these energy practices through the use of smart devices. A growing number of studies have shown that householders experience a lack of control and autonomy in enacting energy citizenship in the smart grid [12,13,22,35]. Moreover, householders express fears that with the smart grid, a market logic enters the domestic sphere [40]. Hence, the easy transition from rooftop PV to new consumption practices and new energy-conscious purchases that we sketched out above starts to hamper with the introduction of smart grid technologies and associated business models. These reconfigure domestic energy practices in ways that complicate people's earlier notions of energy citizenship as prosumption. In distinction to older forms of smart energy, platforms also add a collective logic to the engagements with energy. Platforms bundle do­ mestic energy practices, in the sense that people's practices of producing, storing, and consuming energy in their household are orchestrated in tandem with those of occupants of other households, thus creating (a kind of) collective agency. But the connection of distributed individual households through a digital infrastructure can be accomplished to various ends: as part of an energy community that wants to maximise its PV self-consumption, or as a customer in an energy trading collective. Given these new twin dimensions, we wonder: How do householders experience the new forms of collective agency with regards to energy? Do platforms enable them to engage with issues that they are concerned about, and accordingly intervene in the energy system in a way that is meaningful to them? Do platforms facilitate householders to take up the roles and responsibilities they aspire to take up in the energy system? These questions translate in the following overarching research question: how does participation in energy platforms affect practices and experiences of mundane energy citizenship? In order to address this question, we build on our research in a demonstration project of a “Virtual Power Plant” (VPP)1 in Amsterdam. We surveyed and inter­ viewed participants, coordinated and collaborated with project leaders and organized workshops with its stakeholders. In Section 2, we first discuss energy citizenship from the perspective of material participa­ tion, and explain how platforms can be analysed as a technology for collective participation. Next, we introduce the case of the Virtual Power Plant project, and the methods we used to research the experiences of the householders. In Section 3, we show how the new material en­ gagements that energy platforms offer do not automatically result in meaningful new experiences of energy citizenship for householders. In a nutshell, the householders experienced a tension between acting for the sake of the energy system and working towards one's own sustainability project. Building on these findings, we end by discussing the potentials and limitations of platform-based citizenship in the future electricity grid, and draw out implications for the conceptualisation of energy citizenship in the context of a digitalised energy system. 2. Energy citizenship and material participation With the decentralisation of the energy system, energy technologies are increasingly situated in people's everyday environments. According to an early perspective by Devine-Wright [8], this might lead to occa­ sions in which citizens increase their understanding of energy topics and become more excited about getting involved in them. As Devine-Wright explains it: Energy citizens can feel positive and excited about new energy technologies rather than apathetic and disinterested; be aware rather than ignorant of the scale of its potential impacts on political in­ stitutions, the environment and everyday lifestyles; and be willing to engage not just as individuals but as collectives in shaping techno­ logical change at local, regional and national levels. ([8], p.77) In other words, “decentralized energy technologies can foster new ways of thinking and behaving about energy” ([8], p.77). Not only would people's awareness of energy and climate change issues grow through these close encounters, according to Devine-Wright, gleaning insights from the “environmental citizenship” literature (e.g. [9]), peo­ ple would also develop a sense of responsibility towards future gener­ ations and become willing to engage in collective action. In short, a new energy public would rise up. While we are sympathetic to this argument, in this paper we would like to take an analytical step back. We do not dispute that decentralised energy technologies can foster new ways of thinking and behaving about energy per se, but to the extent that they do, we want to understand how. The literature rebounds with examples in which local renewables did not inspire a greater sense of personal responsibility. In fact, Silvast and Valkenburg [33] argue that the concept of citizenship should encompass both action that supports and endorses energy transitions as well as protest and contestations. In that spirit, we want to propose the following open definition of energy citizenship. We use the term energy citizenship primarily to capture the way people identify a problem of common or public concern and how they allocate responsibility for who is to deal with that problem. Some people will assume part of that re­ sponsibility, others may abdicate it in favour of other actors, such as the state, semi-public (regulatory) entities or even private enterprises. We will also use energy citizenship to refer to the practices that people use to exercise their agency and assume the role they believe or aspire to play. Our subsequent step forward hones in on the processes through which people's interactions with decentralised energy technologies lead to new ways of thinking and behaving – or not. To understand these processes, and thus assess Devine-Wright's claims, we borrow tools from a distinct analytical apparatus: the theory of material participation by Marres (2018). This theory argues (distinct forms of) energy citizenship manifests in relation to specific kind of technologies and infrastructures in people's homes. Especially noteworthy here is Ryghaug et al.'s agenda-setting work on “mundane energy citizenship”. Mundane energy citizenship consists of “awareness”, “knowledge” and “practices” ([30], p.290). This concept therefore hews quite closely to Devine-Wright's conception of energy citizenship, but the addition of its “mundane” dimension is meant to draw our attention to everyday practices, that is, the practical engagement with objects (like, in their case, electric ve­ hicles, domestic smart energy technologies and solar panels). This is, in other words, an objected-oriented approach that builds on Marres' idea that “[s]imple mundane practices, such as turning off the light, driving an electric car, or doing laundry, might become ‘a way of engaging with and acting upon the environment’ (Marres in [30], p. 289). This object-oriented approach is well-equipped to address a funda­ mental process that was left unclear in Devine-Wright's original account: how involvement with “close to home” renewable technology could cause people's affective, perceptive and behavioural shifts. Powered by their new analytical resource, Ryghaug and her colleagues do show how in various ways the devices or objects present occasions to develop new 1 A Virtual Power Plant is achieved through control over a geographically circumscribed, but distributed set of assets of electricity production and con­ sumption, like PV panels, (household or community) batteries, as well as staple household devices, like boilers, heat pumps or tumble dryers. When con­ sumption from the grid, or supply to the grid, can be coordinated (synchro­ nized) across all these assets, simultaneously, they act as a kind of power plant. Control and coordination can be done through direct, remote control of the assets or with the help of building occupants, who might make changes to their device use/consumption. 2 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 awareness, knowledge and practices. Tesla owners had to engage with the public controversy over subsidies for what was perceived by some as conspicuous consumption. In so doing the owners educated themselves about environmental challenges for the transport sector in particular, and by extension, for the energy sector. Some of them even became active supporters of local transition projects. People with smart energy technology at the home reported having become more aware of energy – as the ‘thing’ powering their house as well as an issue of societal concern. Where possible, they shifted their energy consumption pat­ terns, in line with more sustainable use of the electricity grid. Finally, more speculatively, the authors argue that once energy consumers become ‘prosumers’ through their acquisition of PV, energy itself can acquire different meaning (something of a local common pool resource) and that it can push some to revise their energy consumption practices (like shifting energy intensive activities to when the sun shines). Like EVs, PV panels are publicly visible objects and as such can elicit dis­ cussion with others, whether about their value or as object of joint co­ ordination, if they become part of a community project [30]. This valuable analytical lens thus fleshes out Devine-Wright's early ideas about energy citizenship in relation to technologies: as people get more practically involved with (the) energy (system) – through key devices and technological objects – they can take up new – and positive – stances towards energy. People are relating to “political matters of concern” ([30], p. 285) through mundane activities (through which they are becoming more aware about these matters in the first place). In other words, Ryghaug et al. develop an understanding of how people's engagement with energy-related technologies derive their meaning from being able to ‘act upon the world’, take responsibility for it, and thus be part of something larger. Table 1 Quadrant of material participation in the energy system. Unilateral Bilateral Individual Technologies: Solar, smart meter, in-home displays Generating energy for own household and monitoring household energy flows Participation in energy system via FIT/net metering Collective Technologies: Solar, wind Generating and providing energy to local communities (and/or grid) Participation in management, ownership and/or operation of the installation and in decisionmaking on (financial) returns Participation in energy system via FIT/net metering/other policies for collectives Technologies: Solar, smart meter, smart household appliances, batteries Generating energy and monitoring for own household and grid, providing flexibility to grid Participation in demand response markets Technologies: Solar, smart meter, smart household appliances, batteries, platform technologies Generating energy and monitoring for own households and grid, providing flexibility, energy trading Participation in demand response markets; local and national energy trading markets (feed-in tariff). We refer to this as the unilateral quadrants in the matrix below. Individual consumers and prosumers can also participate in the management or governance of the energy system through newly designed smart grid markets, like demand response. We call this participation in energy system governance because here individual households contribute to the stability of the grid. This is participation on the bilateral side, because with smart grid markets a dynamic two-way relation between households and the energy system is constructed, in which households do not just generate energy, but also become responsive to the needs of the grid. While this co-manager role [40,51] may result in positive engagement with energy, critical questions have been posed about the unequal capacities and resources of different people to take up this role [26,38]. With the advent of the (community) energy platform, people can enter energy markets as collectives [16,24] in diverse ways. It is a col­ lective form of participation, because all the resources from the com­ munity are pooled by an aggregator, which in the context of energy means that energy production, storage and consumption across participating households are assessed as a whole, and their use and impact directed according to set objectives. One application of this technology is when the aggregator steers storage devices and sometimes (people's use of) household appliances to trade energy on behalf of the collective, while other applications include assistance in grid congestion management or maximising direct absorption of local PV electricity through demand-side management [19]. In a community energy plat­ form the user thus becomes a participant in regulating the safe ‘coop­ eration’ of renewable assets with the rest of the electricity grid, so as to maintain grid stability. Practically, it means participants becoming ‘responsive’ to the needs of the grid. Now, because trading and demand response are (almost always) organised through energy (wholesale) markets, this kind of energy stewardship works by getting remunerated in exchange for being flexibly responsive [19]. This thus fills up the fourth slot in the quadrant of material participation. To analyse how platforms afford participation in the energy transi­ tion, we follow Ryghaug and colleagues, and conceptualise energy citizenship as emerging from everyday mundane engagements with technologies. These everyday interactions with technologies then open up ways for people to engage in energy issues via processes of aware­ ness, knowledge and practices. On the surface, one might expect energy platforms to be yet another opportunity for positive energy citizenship to grow out of new close-to-home encounters with (renewable) energy. We note two grounds for doubt however: Firstly, the inherent complexity of grid management makes this into a qualitatively different encounter than the material engagements with renewable energy in the 2.1. The platformisation of energy citizenship Meanwhile, renewable energy is changing the grid profoundly. De­ centralisation of energy brings about complexities in the energy system that do not only offer opportunities for (positive) engagement, but can also frustrate such engagement. Ryghaug and her colleagues acknowl­ edge as much at one moment, when they mention that new technologies can cause friction and new business models in the sector might introduce new complications ([30], p. 296f.). And indeed, users' experience with various ‘smart grid’ solutions has been less positive or at least more ambiguous [10,13,25,36]. These solutions are often in some way problematic: people experience them as incursions on daily routines, as constraints on agency, rather than as opening up a new field for meaningful engagement. The advent of energy platforms may bring about similar tensions and ambiguities. Energy platforms make use of smart grid technology and create new energy collectives. More specifically, as outlined by Klop­ penburg and Boekelo ([15], p. 69), energy platforms “make use of a digital environment […] to facilitate transactions between (small scale) energy producers and consumers”. One can distinguish between different kinds of platforms according to whether they merely record energy flows or intervene in them, whether they are primarily geared towards connecting small-scale energy assets or aimed at (financing) the development of new ones, and the degree to which they algorithmically take over from the user (or asset owner). In this paper we focus on the kind that intervenes in the flow of energy, or what is called “community platforms” [15]. These community platforms in particular offer the new possibility of collective participation. If one were to imagine a quadrant of material participation, up until recently there were three slots open in this quadrant (see Table 1). People could get involved in energy generation as individuals (prosumers with their solar panels) and as collectives (co­ operatives buying into or owning solar and wind installations). In terms of participation, this was fairly straightforward: people hook up their panels or wind turbines to the grid, consume the energy themselves, and feed the excess energy into the grid in exchange for a monetary reward 3 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 unilateral column above. Secondly, so far, platform technologies that operationalise this market-as-governance have been developed by util­ ities and power companies. It is an open question whether the latter actors have managed to design these technologies such that they also sync well with collectives' desires for meaningful contribution to the state of the world. We suggest that participation in energy platforms does not necessarily result in active and positive engagement with en­ ergy because platforms introduce new uncertainties and complexities in the relationship between people and energy systems. Our entry point into understanding these complexities are the experiences of house­ holders who volunteered to test out an energy platform in Amsterdam. the participants. At this moment in the project, the participants' batteries were connected through an ICT control module and the pooled energy was used for trading energy on the national energy market. The first workshop (held in June 2018) involved participants only and consisted of gamified discussions about what values should undergird a VPP and how that could be operationalised into an actual VPP design. In the second workshop (November 2018) the project leadership was present too and here we organised debates around a number of statements about what a VPP should accomplish, provide, or enable members to do. These statements were based on the earlier workshop as well as the interviews. By opening up such questions for active deliberation, we invited the participants to reflect and discuss issues of energy platform ownership, operation and management, as well as wider energy system governance. The workshop thereby enabled us to examine this new energy collective as an emerging public: how the participants as members of this new energy collective understood and discursively positioned themselves visa-vis the project leaders and the energy transition more broadly. The combination of these two main sources of data – interviews about daily interactions with energy technologies and the workshops to engage people in a broader public consultation – thus provide a unique oppor­ tunity to gain insights into how energy platforms affect existing enact­ ments of energy citizenship and enable or frustrate new enactments. The interviews and the first workshop were recorded and tran­ scribed. We analysed the transcripts thematically by focusing on the three dimensions of mundane citizenship: awareness, knowledge, and practices. In our analysis, we approached people's experiences with renewable technologies as a trajectory of energy citizenship, which we charted starting from the acquisition of PV panels to the current participation in the Virtual Power Plant project. Below, we first examine how interactions with PV panels shaped awareness, knowledge, and practice that resulted in a form of energy citizenship that is centred around the home as a site for individual action and responsibility. Then we look into the expectations that people had about how their partici­ pation in the VPP would affect their agency and responsibility with regards to energy issues. Next, we look at how the pilot introduced two new material devices in the household: a battery and an accompanying digital interface, and how these devices affected the established prac­ tices, knowledge, and awareness. In the final empirical section we report on people's experiences in participating in the VPP. Here we base our findings on the workshop that took place in year two, when the VPP was operational. The key aim is to analyse this trajectory of mundane energy citizenship in terms of shifts in awareness, knowledge and practices, and how people experienced diminishing or expanding agency and re­ sponsibility with regards to energy issues. 3. Research methods As mentioned, our observations stem from a pilot project for a Vir­ tual Power Plant in a suburb of Amsterdam. The project was initiated by a consortium consisting of a grid operator, a green energy supplier and an energy platform provider. For the project, which ran between March 2016 to February 2019, 48 homes with rooftop photovoltaic solar cells (PV panels) were outfitted with a 5 kW battery, free of charge. Project partners then sourced and developed the VPP software that could pool the participants' renewable energy resources (PV panels and batteries), turning the 48 households into a virtual collective that could experiment with new forms of energy exchange, including providing grid balancing services and trading energy on energy markets. The aim of the project was to test and get insight into the impact of virtual power plants on the energy grid and the possibilities to use VPPs to manage net congestion. An additional aim was to see if householders would be interested in engaging in a VPP, and more specifically how they would experience participating in electricity and flexibility trading. The project was implemented in a neighbourhood in Amsterdam where grid congestion was a problem already. In this neighbourhood, private homeowners who had already installed solar panels were invited to participate. The presence of solar panels was a requirement because the self-generated electricity would be used for trading. The home bat­ tery came in to store that energy in order to trade it at favourable mo­ ments. The promise was that any profit earned by trading energy would be shared with the participating households, but any additional costs would be borne by the energy provider. At the end, people would have the choice to keep the battery or to return it to the consortium. People were invited to sign up for the project via ads in a local newspaper as well as direct mailings. Two information meetings were held in the neighbourhood. This resulted in about 50 people to apply, some of who could not be integrated, because their homes could not accommodate the battery. A survey among the first 25 households to enrol in the project showed that the vast majority of respondents (one per house­ hold) was highly educated, working as professionals (with a few re­ tirees), ranging from lower middle class (€2000–€2500/m) to upper (middle) class (more than €5000/m net income). Average household size was 2.7, mean size was 2. The geographical area of recruitment included all households connected to an electricity substation, which meant that the households that signed up did not know each other yet. Our role as social scientists in the project was to examine the expe­ riences of the householders in the project. During the two-year period in which the VPP project was actively implemented, we engaged with the participants at different moments. In the early phase of the project, after the aforementioned preliminary survey, we conducted 19 interviews with participants who had just entered the project. At this point, most of them had already had their batteries (recently) installed in their homes, but the batteries were still in passive domestic consumption mode. Our interviews with the participants served, firstly, to take down their en­ ergy biographies – usually starting with the moment they got their PV panels up until the present moment. The second goal of the interview was to understand their motivations to join the pilot and to talk about their early experiences with the installation and use of the battery. In the second year of the project, we organized two workshops with 4. A trajectory of energy citizenship: from solar to platform 4.1. Engaging with PV panels: awareness, knowledge, and action at home As noted by other scholars [11,37,38,50], and reiterated by pilot project participants, the installation of solar panels triggers new behaviour. People start checking their ‘production’ and often they will also start reconsidering how they consume energy. As one of the par­ ticipants explained this: “What I liked was seeing what you yourself perceive in terms of sunshine and what that would mean in terms of PV production”. People learn to read the weather in terms of energy potential and thus reshape their perception of the world. We come back to this wellestablished point in order to emphasize that this new behaviour trig­ gers a new perception of the (physical and social) world. In fact, we argue, getting solar panels triggers a process through which people mould their subjectivity as energy citizens. For such a change in perception is about more than just the weather. People also start developing a feel for how much energy runs through the household, particularly when they have smart energy monitors that show real-time energy production and consumption data. The PV panels and smart energy monitors have given them a new resource in the calibration of 4 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 their behaviour in terms of energy consumption. Crucially, this practice of monitoring energy production is not a su­ perficial process – it is affective. Many people really enjoy watching how much their PV panels yield. Moreover, because of the (initial) frequency of monitoring and the positive valuation of PV-generated electricity, the practice acquires something of a ritual. Ritual, as anthropologist have pointed out, cements disposition: feelings about and views of the world (e.g. [1,7,41]. Ritual, it seems, also cements people's connection to their panels. In the following interview excerpt, one of the pilot participants describes how solar energy makes her feel. Note how the first person personal pronoun is – affectionately – used to refer to the solar panels, signalling a degree of affective identification: leaders thereby addressed them explicitly as energy citizens who actively take responsibility for the system. The participating households themselves, however, held varying expectations about what the project would bring. Drawing on their existing energy practices and experiences of citizenship, some people hoped that their participation in the VPP project would make them even more aware of their energy consumption and improve their energy consumption patterns at home. Others saw it as a matter of preparing for the future, and to be ready to make the right (financial and environmental) choices: [A project like this] is an educational moment – in this sort of pilot project, you deal with all the growing pains, but the advantage is that you understand, like, ‘wait a minute, I need to think differently about this’. (Philip) I enjoy getting [energy] from my own panels. Like, I also have a greenhouse, with my own cucumbers – I like those much better than the ones I buy, you know. It's about that feeling. To a certain extent, I think, it's about being independent: you don't have to acquire it from outside –you're self-sustaining. I find it quite satisfying that you can take care of it yourself. We're not really the kind of people who make their own bread or whatever, you know. But I enjoy this: [to see] this is how much I generated today – I can totally run my household on that! (Margriet) This includes the broader societal embedding and implications of this kind of technology: You get the chance to think about it and give your input […]. What's interesting about this project, is that it has this social component. A lot of people are going to think that they are all ‘green’ now [but in fact, as he just explained, lithium batteries are far from ‘green’]. I like that sort of discussion. That you start to think a little more, that it's not just financial, but also about the environmental dimension and about where you want to wind up in the long term. (Ernst) Participants themselves felt like this change in perception changed them as responsible persons and as members of society too (much like the Tesla owners in the study of Ryghaug and colleagues). When people talked about being aware or becoming conscious about energy, they suggest, albeit mostly implicitly, that such awareness could lead to behavioural change and better choices, whether by buying new energy efficient devices, taking alternative modes of transportation more often, or eating less meat. This language of (environmental) consciousness is why we argue that the shift in perceptive ability enables people to mould their subjectivity (as citizens). Becoming alive in this way to energy has further implications for perceptions of the world: people became more knowledgeable. A few mentioned actively keeping up on environmentrelated news, while others spoke of picking up on energy related is­ sues in the media, in a more organic way. One couple, in their early retirement, recounted how they “discovered it was good” to wash when the sun shines and that they found out it makes sense to replace your big household appliances after 7 to 8 years. And so they did. All of this shows that as people develop new domestic energy prac­ tices of monitoring around domestic PV generation, they become conscious about energy and actively seek out or become more attuned to relevant information, which in turns makes them ‘more aware’ of the climate problem, and all its implications for policy and their daily life. The type of energy citizenship that emerges here is one in which people take responsibility over their own domestic domain: by investing in solar energy, in reducing energy consumption, and perhaps through some other ‘responsible’ choices or behaviours, like changing food habits or mobility routines. People talk about this trajectory positively, as one of expanding agency and positive feedback. PV, in other words, is really a quite ‘successful’ technology – panels work, on the whole, as advertised, and they open up new, meaningful experiences and a path for engage­ ment for many of their owners. For the participants in the VPP project, the experience also opened them up for new knowledge and made them sensitive to the pitch that the VPP demonstration project leaders slid through their letter boxes: an invitation to be part of the future of the energy grid. These are examples of how people imagined their participation in terms of further awareness and expanding agency: learning and making up their own minds about new questions and issues. But this was certainly not the only role that people conceived of for themselves (and by implication, for other parties): Secretly, me and my wife, we talked about this, after we registered for the project, maybe with a windmill in the mix, we could sever [‘hack’] the cable to our energy provider - I like that idea a lot, the idea of self-sufficiency. […] I can just picture it - with a big axe, awesome! [Laughs] Nice. (Dennis) Here the concept of the Virtual Power Plant triggered fantasies about a new relationship to energy in the local neighbourhood: that of energy autonomy. Becoming part of a virtual energy collective was something people were interested in, but many found it difficult to imagine what it could look like in practice. Several people thought it was “cool”, or “a lot of fun” that individual (power) capacity would be bundled, and at a later stage possibly even shared in the collective. The idea of doing things ‘together’ thus resonated with some participants, but what such a ‘together’ would have to look like was still quite unclear at the moment of the interviews. The same actually went for collective independence or self-sufficiency. It's “an interesting idea that you can provide in your own energy as a small group”, as one woman put it. While this idea remained mostly abstract, the prospect of relating differently to energy was an attractive one. As she explained further: “You read about it in the newspaper every day, we can't go on like we've always done. So if someone offers you an alternative, you should get on board”. This shows that people expected further posi­ tive engagements with energy through developing new knowledge, further awareness, and collective practices in the VPP. 4.3. Engaging with batteries and interfaces: frustrations and uncertainty in participation in the Virtual Power Plant 4.2. Energy citizenship in the Virtual Power Plant: expectations of further positive engagements with energy Participation in the VPP project meant that residents got a home battery installed in their household. For some people, the battery turned out to provide another device to calibrate their perceptions of energy, with people going into guessing games (with themselves) about whether the wintry sunlight would be able to fill up the battery that day. For others, the battery as an energy storage device demonstrated the value of a kWh: In the process of recruiting participants for the VPP pilot project, the project leaders emphasised the new possibilities for households to contribute to the energy transition. By joining the VPP, people would collectively help address the problem of matching demand and supply of energy in a decarbonising and decentralising energy system. The project 5 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 It's actually kind of funny, if you look at this process of becoming more conscious, you really become quite aware of what it means to generate power, how much a kWh is, and what that means for how much you can use. But if you look at your basic plug-in hybrid, with 8 kW and it can go for 30 km or whatever, so the values are finally starting to get through to you. It's a really a process of becoming more conscious. (Philip) steering of the batteries would offer new opportunities for participation in the (transition towards a cleaner) energy system. In the next section, we move to the workshop that we organised in the second year of the project, when the batteries had been connected and the pooled energy could be used for different purposes. In this workshop the participants met each other for the first time to discuss different values, roles and responsibilities with regards to grid balancing, trading, and selfconsumption. How did people respond to the idea to engage in these collective practices, and to the new modes of citizenship that the plat­ form could offer? The battery came with its own interface, showing production, con­ sumption and storage of energy. However, as people started using this interface, many of them felt a little frustrated by what they encountered. The technically inclined participants who dove deep into the different graphs found the information inconsistent with what they thought was happening or ought to be happening in their household. In part, the problems they were running into were due to the experimental nature of the pilot, in which the batteries became a persistent bottleneck for the project leaders: the batteries experienced significant efficiency losses and turned out to be inaccessible to remote read-outs. However, it wasn't solely operational and logistical issues that constituted problems for participants. The fact itself that the battery was interjected into the energy household made things in themselves confusing. For the following quote, a couple in their late fifties were talking about how the battery disturbed their routine practices of monitoring the performance of their solar panels: 4.4. Deliberating mundane energy citizenship in the future grid As we have seen, for many people, awareness of the problem of climate change and the necessity to transition away from fossil fuel had grown over the years, and most saw their engagement in the VPP project as a next step in a trajectory of becoming more sustainable and selfsufficient as a household. Their experiences with the fluctuating avail­ ability of self-generated green energy had also made them aware of new issues such as the challenges of decentralised renewable energy pro­ duction and (further future) electrification for the grid. In the workshop one of the participants reflected on this: If things continue like this, with decentralized energy generation, and we all want to drive electric cars, well, then all these houses need 3 × 80 Volt, because you don't get there with a simple socket on the wall. So all cables will need to be replaced. And think about it: in a city like Amsterdam, with all the canals, that's simply impossible! Until this installation [of the battery], things were very simple. The digital meter indicated how much Watt you're generating every hour, and by the amount you fed back into the grid, you can deduce the solar yield. […] I cannot see that anymore, because it's going into the battery. (Peter) The idea that a VPP could facilitate the integration of renewables in the grid was familiar to many of the participants, and during the workshop a discussion revolved around the role of batteries and VPPs in addressing systemic issues: If we don't actually consume the energy from the panels, it goes into the battery, which means you are not feeding into the grid, which means you can't track things through the meter. So I am very curious how all of this is going to go. (Saskia) P1: Right now the grid is congested, but those batteries will help to relieve that because we store [the energy] ourselves. P2: But if we all have those batteries, and because of those batteries the grid will get congested [when they charge from or discharge to the grid at the same time], and then the hospital won't have power… More people were puzzled about a more elementary question too: how can the battery interface give me any accurate information about what is happening in my household, if the energy company and VPP aggregator take control over my battery? Such questions relate to the fundamental architecture of the VPP: a battery is inserted into the household, one whose state of charge doesn't depend only on things that go on within the household. Then there was the interface itself. It was not created with ordinary consumers in mind (probably more with system administrators), and so the visualizations of those dynamic de­ velopments were often experienced as confounding. As one of the par­ ticipants put it: “I've tried to make some headway, but then, I'm like, whatever, I already don't get it any more. But I know it can be very simple! It has to be simple - that you can see it”. The participants wanted to under­ stand, but felt frustrated in this desire. “It's very important to know what you're doing”, as another person underscored. Other studies too have shown how using a home battery can cause uncertainty (what is the battery doing, why is it making noise?), and a sense of disempowerment with regards to the workings of the battery [27,35]. Yet, while previous research understood such frustrations about the battery as the result of failed interactions with a material device, here we understand them as stemming from the disruption of an established mode of energy citizenship. In the VPP project, people's agency, in the sense of their capacity to reflect on and act with regards to their domestic energy production and consumption, diminished. People could no longer monitor if and how their everyday practices contributed to their broader goals (e.g. of being sustainable). Due to the remote control over the battery they also lost their grip on how the energy flows ran between the household and the grid. In other words, the new practice of storing energy disrupted established practices of monitoring and managing energy flows in the household that were the foundation of people's sense of energy citizenship. Was something else going to make up for this? The project's promise was that the remote and collective This small exchange shows that people become aware of the com­ plexities of grid management, but that they are uncertain about the ef­ fects of their storage practices on redirecting energy flows. The uncertainty here was not just related to the exact systemic effects of energy storage, but more importantly, whether through their partici­ pation in a VPP people would be contributing to a good cause. When they discussed the possibility of joining an energy platform aimed at providing grid balancing services, people also perceived that aim in light of the larger ‘project’ they cared most about: becoming more sustainable: P1: Are we enhancing sustainability when we're trying to improve the stability and affordability of the grid? Are we making things more sustainable? Or…? P2:No, you're not making things more sustainable that way. P3: but you NEED that [a stable grid] to make that development, that shift towards fossil-free! All this suggests that with this new awareness of energy system issues also come new uncertainties about people's own role and agency through the energy platform. The earlier ‘simple’ practices of generating and managing energy at household level through which energy citi­ zenship was enacted are supplemented with collective energy practices that make people aware of, and reflect on, energy system issues. This introduces complexities to the trajectory of becoming more environ­ mentally aware: it is no longer so clear what it means to ‘be green’. The new collective practices that the VPP made possible – grid 6 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 balancing, energy trading, collective self-consumption – thus also sparked a discussion among the participants about their own role and about the allocation of responsibility. Who is in a position to act? Which forces should be rallied in order to foster energy transitions? What ties to be established? Some people were very enthusiastic about contributing to grid balancing, and one workshop participant argued that: ‘Look, we ourselves do not control getting rid of our dependence on fossil fuels; that is much more up to companies. Large companies, that is where the problem lies. I believe we are much better off if we, together, ensure that there is a stable energy grid.’ In this quote, grid stability is perceived as one of the issues where the collective action of citizens is a form of agency that creates positive impact. This idea that people could take responsibility for the stability of the grid, however, did not appeal to everyone. In the same discussion, someone else distrusted the motivations of other parties to involve citizens in this: derailment of the journey of becoming more sustainable that people had embarked on. The material participation that platforms offer thus on the one hand provides occasion for developing further awareness of the complexities of a changing energy system and for collective energy practices to create experiences of positive engagement with energy. On the other hand, the bundling and remote steering of energy practices complicates notions of responsibility and agency, as it makes it more difficult for people to oversee the effects of their actions. 5. Discussion What do energy platforms offer in terms of collective participation in the energy transition? Our findings show that everyday energy citizen­ ship in the sense of ‘doing good with your energy’ becomes complex with the emergence of collectivising technologies such as Virtual Power Plants. Being an energy citizen now goes beyond ‘having your own house in order’, and requires people to reflect on their position in relation to new issues such as grid balance, and the ‘greenness’ of various energy markets. In doing so, they also need to reflect on their own agency vis-a-vis the collective agency that results from the bundling of energy practices of all households participating in the platform, and vis-a-vis the power and motivations of providers who offer and control such new ‘collectivising material devices’. For the households in our research this was a frustrating endeavour. The new collective actions complicated the participants' sense of agency with regards to energy in the situated contexts of the home, because people were not sure if the goals of their individual ‘project’ and those of the platform were aligned. People's concept of agency was further unsettled because the platform worked ‘in the background’ and automated collective actions and decision-making without much feedback to users. Third, interacting with the VPP platform also meant that people needed to (re-)consider their ideas and practices of ‘making a positive impact’ with energy in relation to the rationalities of grid and electricity markets. The VPP made people responsible for issues that previously lay outside of their direct sphere of influence (e.g. grid balance, local self-sufficiency). While some respondents experienced this as an opportunity to take on an extended responsibility, others questioned or even resisted the po­ sition assigned to them by the platform. Hence, because the households in our research lacked insight and feedback on real time production and consumption data of the collective, and how this impacted energy flows in their own household, this created a (perceived) tension between acting for the sake of the energy system and working towards one's own sustainability project. This poses a serious design issue, because if greening the grid will depend on citizen participation to ensure its sta­ bility, energy platforms need to make clear what their value proposition is. This becomes even more important when we consider other trajec­ tories than that of individual PV owners who at some point may decide to join a platform-based collective. Energy cooperatives, for example, are collectives that predate the platform collective. Their active involvement with energy generation already goes beyond “participation through using domestic devices” and extends to ownership, manage­ ment and operation of energy assets and infrastructure [44,48,49]. This may include collective decision-making over the purchase of assets such as turbines or solar panels, which itself entails public deliberation over the future of common or collective resources [2]. In other words, energy cooperatives have already construed a sense of who they are, and what they want to accomplish collectively. Energy platforms such as VPPs can be attractive for cooperatives, because this technology can enable them to exchange energy via local energy markets and achieve goals such as local self-sufficiency [46]. Taken energy cooperatives' existing trajectory of collective energy citizenship, we can expect that they want to have a say not just in the specific way energy platforms are operated for the sake of the energy system, but may also want to operate and even own such platforms themselves. If energy platforms are to play a supporting role in the next phase of the energy transition, the ‘match’ between The grid belongs to the grid operator, and the grid operator wants to run it as economically as possible. So what do they want? Postponing investments! We help them to make their cables last longer, and that means they can postpone an investment of billions?! I absolutely don't pity them! Likely because of their historical trajectory as energy citizens who learned to optimise their household energy consumption, the idea of an energy platform that aimed at CO2 reduction (at neighbourhood or even just household level) resonated a lot better with the participants. As one of the participants argued about her role in such a VPP: It's a collective endeavour, and it supports a good cause. The second argument is that it's close to myself, to what I do as a person to reduce that CO2 footprint of myself and my family. That's what I can have an impact on. In this line of reasoning, the abstract issue of climate change is made tangible and translated back into the domestic or personal framework of the CO2 footprint. The VPP then would link domestic practices and en­ ergy citizenship in a similar way as the solar panels did, but now in a collective sense. Yet, there was more to this desire to ‘keep matters in your own hands’. The workshop participants showed a general scepti­ cism about energy companies and grid operators making money with new ‘services’ such as grid balancing or trading energy on the national energy market. As one participant said: For all we know the fast guys will run with this and start speculating, that's what they all do nowadays! […] There's always people who will think ‘how we can make money out of this, how to best make money from someone's green identity?’ This person was not alone in his fear that a VPP could mean a ‘marketisation’ of their energy citizenship: Look, my goal, myself, I want to – with my house, with my battery – to be energy neutral. I don't want other parties to earn millions from my battery. This shows that the role of the energy citizen that most people conceived for themselves is still very much based on taking re­ sponsibility for their domestic domain, through practices that are focused on household goals, like being “energy neutral”. Another participant pictured a horror scenario in which he would come home in the evening to find out that “the provider has decided to drain the battery completely” in order to trade the energy, so he would lose what he had saved during the day. These conceptions of energy platform providers whose commercial logics go against or frustrate people's positive en­ gagements with energy also brings up a more fundamental difference in the perception of what energy is. As we have seen earlier, most people viewed energy as a resource they grow, manage, and harvest in their domestic sphere. VPP models that aim at grid balancing and trading, however, bring a different conceptualisation of energy: as a commodity that is subject to market logics. Such other logics can be experienced as a 7 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 cooperatives' goals and energy platform rationalities needs better alignment [20]. This requires increased transparency and feedback about the social, economic, and environmental benefits and trade-offs of different goals of platforms (local and national-level energy trading, grid balancing). Looking more broadly, the question comes up for whom energy platforms create new possibilities to participate in the energy transition. While the literature around new platforms and their business models is growing [3,6,21,32,45], there is still little empirical analysis of who can participate in them, and whether these models enable people to participate in the energy system in a way that is meaningful to them [34]. Thus, Silvast and Valkenburg [33] note that the literature on en­ ergy citizenship often does not pay much attention to the gender, age, ethnicity, and socio-economic background of “energy citizens”. The “energy citizen” that energy platforms target so far, and also the par­ ticipants in the pilot project we examined, are resourceful prosumers. In reality, not everyone can afford to acquire solar panels and home bat­ teries, and not all households are equally flexible in adapting their en­ ergy consumption to the needs of the grid by time-shifting their domestic practices [26,36,38]. The experiences of the respondents of our research thus should not be generalised, but interpreted and contextualised in light of their specific historical trajectory of citizenship, recognisable to many resourceful prosumers, one which builds on their positive en­ gagements with energy through PV technologies. At the same time, platform business models are quickly diversifying, and new groups may be drawn into platform-based energy. For example, some energy platforms provide assets such as solar panels and batteries to households in return for (partial) access to and control over these assets. Such platforms are often promoted as a means to reduce the financial barriers for consumers to purchase and use devices such as batteries and electric vehicles. In the future, people could also get involved in platform energy when they relocate to a newly built neighbourhood in which (flexibility) assets and energy management systems are already installed in homes and the built environment. Based on our ‘trajectory-based’ analysis of citizenship, we may expect these developments to open up new forms of energy citizenship as well. The existing energy citizenship literature does not look well-equipped to accommodate these dynamics of citizenship. Many authors, in fact, implicitly or explicitly, only qualify the pro-active and positive engagement of the resourceful prosumer as “energy citizenship”. Only when people take on responsibility are they ‘citizens’. But if citizenship is a perception of an issue, a perspective on who is responsible for resolving it, as well as the practices that express that perspective, then passiveness can be as much an act of citizenship as active engagement. This position can help clarify and answer the question raised by Wahlund and Palm ([47]: 10) about there being any space for “non-participation” in smart energy-connected homes, or whether everything becomes ‘citizenship’. In a hypothetical case of a smart energy-equipped new home, where flexible responsiveness is automated, its new occupants might go through their day oblivious to the enlistment of their house in governing the energy grid. Such oblivion (‘non-participation’) is not a matter of energy citizenship in our sense.2 However, as soon as they consult dis­ plays or apps and their awareness changes, they start relating to energy as an issue – whether they stay ‘passive’ or change energy practices.’­ Passivity’ is therefore not necessarily a matter of non-participation. Citizens may feel it's right to outsource responsibility for energy issues to other actors such as aggregators, just as they might rebel against the ways in which responsibilities are designed by a platform (as many of our respondents did). Both are modes of participation. The benefit of material participation theory here is clear: it helps us operationalise this more agnostic approach to energy citizenship and uncover the diverse modes and experiences of energy citizenship that can emerge in different settings. Questions about who participates in platforms and under what conditions are not just a matter of research, but vital questions for a democratic and just energy system. While the everyday, material dimension of platform-based energy citizenship is taking shape as platform technologies start to spread more widely, the possibilities for citizens to influence this development and its direction so far seem rather limited. An important reason for this is that many energy plat­ forms and their development offer practical engagement, but do not offer (adequate) discursive space to enable collective discursive partic­ ipation and reflection. This brings us all the way back to the beginning of this paper, to Devine-Wright's prediction that close involvement in the (transition towards a renewable) energy system would foster the growth of a new public. Based on our observations in the Amsterdam pilot, we would tend to concur: people told us about how they were now paying increased and different attention to energy in the media and conversa­ tions with family, neighbours and acquaintances. In addition, the workshops we organized midway through the VPP pilot showed that people were eager to exchange opinions and deliberate about the contribution they (individually and collectively) would want to provide, and how and why. But there is no sign that similar deliberative spaces are being integrated into the deployment of next-generation platforms. We want to pause for reflection here. The link between everyday engagement and public stances was key to Devine-Wright's perspective. We have used Marres' “material participation” as a lens to flesh out how such a link might be established. For Marres [18], holding the connec­ tion between these two types and sites of participation – material and domestic, discursive and public – is absolutely essential.3 People relate to topics of (public concern) though everyday, material forms of participation. That means they come to the table with already existing commitments. However, these commitments and practices are often overseen. The energy sector in particular has not outgrown its percep­ tion of people as economically rational agents. It undergirds many of their models and simulations. As long as this is the premise upon which people are approached, it leads to inappropriate terms of engagement and unconstructive face-offs [18]. But when these material forms of participation do become visible and legible, it opens up a different space for dialogue and deliberation, meeting people where they're at. It is therefore high time to open up that space for public deliberation about the values that should undergird a future digitalised energy sys­ tem [23,43]. There are pressing questions with regards to the benefits and risks of digitalised energy system, as well as the right and ability to hold energy and political actors and their decisions to account. The need for citizens and communities to deliberate about platform-based energy will only grow, when EU legislation on the role of prosumers and energy communities is transposed to national contexts. The revised EU Energy Directives have called ‘energy communities’ into legal being and allotted them the rights to generate, store, consume, and sell energy (cf. [28]). Energy platforms can provide the aggregation services and user interfaces that would enable this, but space needs to be made to discuss values, roles and responsibilities between the community members and the platform provider. Based on our findings in the demonstration project, we can identify a 3 Note that Marres actually denotes both material and discursive practies as “public participation”, in order to mark that they're two sides of the same coin. Ryghaug et al. [30] follow this convention. While we appreciate the intention, we have opted to maintain the symbolic distinction between domestic and public, alongside the material and discursive, in order stay more in line with conventional understanding of the term ‘public’ in particular. Therefore, we have subsumed everyday material participation under the banner of citizenship (rather than the public), in order to understand and explain that also through domestic actions, people ‘act upon the world’ and contribute to something bigger. 2 Though one may wonder about the political economy of energy citizenship – what are the affordances for people to gain awareness about an issue and subsequently to relate to it – practically, materially or through representation? 8 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 number of key questions: What are the (economic, environmental) ef­ fects of the community's participation in different energy markets, and what values should be prioritised? How to distribute the costs and benefits of the new energy transactions within and beyond the virtual community? What information should platforms provide to their users about directions and provenance of energy flows? How should owner­ ship, control and use of material assets and platform infrastructure be organised? Which parties should (not) have access to household energy data, and for what purposes can this data be used? Participation in such discussions and making up one's mind about these collective governance issues goes beyond what is currently common for and expected from citizens and communities. What new publics will rise up and how this will impact energy democracy dimensions of popular sovereignty, participatory governance and civic ownership [14,39] is an important subject for future studies. and how seek to regain a sense of control. It also recognises the new complexities digitalisation raises for people's efforts to be green or so­ cially responsible, as well as the enthusiasm and confusion that arises from engaging in technologically-mediated collective action. Our empirical findings suggest that it is important to understand people's participation in energy issues as part of a trajectory they are on. The “energy citizen” is by no means fixed, but develops in a particular context and through everyday interactions with technologies. ‘Accep­ tance’ of energy technology and ‘public engagement’ in transitions is therefore also not a one-time thing. Not only does the technology keep evolving (and thus remain in periodic need of re-evaluation), but people accrue experience and information over time through their interactions with technologies, according to which they also evolve their (dis)posi­ tion. For policymakers and project managers, this means that they have to think about how to create meaningful engagement over longer pe­ riods of time, to create the conditions of possibility for people to develop their viewpoint on new energy measures and the introduction of new technologies. We also draw a design lesson from the experience of research participants: when the scale at which people are enlisted to act goes beyond the household, there need to be feedback mechanisms that show the effects of their energy practices. As long as these mechanisms are absent, there is a risk that new energy technologies frustrate rather than promote people's engagement with and support for the energy transition. From that frustration, disengagement rather than engage­ ment, may well follow ([4]: 676). Platform developers will need to design explicitly for people to know that they are doing ‘their bit’ – that quintessential scope of everyday material participation in energy issues, so far. 6. Conclusion Does closer involvement and interaction with local and distributed energy provisioning lead to greater engagement with and support for the energy transition? This is what much of the literature about energy citizenship has presupposed or postulated for a long time. This article intended to revisit this assumption by attending to the mechanisms through which this process would have to work. With the help of the material participation approach, we investigated how energy platforms as technologies of material participation shape practices and experi­ ences of mundane energy citizenship. Our main contribution to the literature on energy citizenship is to show the daily material interactions through which people's citizenship emerges in relation to energy platforms. We found that the relationship between interaction with distributed energy infrastructure and engagement with and support for the transi­ tion is not necessarily always positive. Participation in an energy plat­ form can trigger householders to reflect on what energy is and how their self-generated energy can be used to support the energy transition. At the same time, a peculiarity of the latest generation collective demand response energy systems is that the platform draws the household into the (management of) the energy grid, at the same time as it decentres the household in a collective arrangement. This need not necessarily be a source of problems per se, but in our case study, it caused friction. People with experience with rooftop PV wanted to expand their sense of citizenship through engagement with the energy platform. This new system, however, disrupted pre-existing interactions and feedback mechanisms, which had cemented people's sense of their role in, and contribution to, the energy transition – without replacing it with an adequate mechanism in return. It thus contracted their sense of agency and responsibility. What do these findings mean for the future of energy citizenship in a digitalised, low-carbon energy system? We sketch out an answer to this question both for research on energy citizenship, and for the practical implications of mundane participation in the energy transition. Some scholars argue that the digitalisation of the energy system is driven by a neoliberal logic of anti-politics in which human agency is reduced or removed from energy systems ([31], p. 2), and the space for citizens to deliberate and challenge decision-making has been dimin­ ished [29]. This would mean that the potential for energy citizenship in the future grid would be small. Yet, such critiques risk missing how through everyday engagement with digital technologies, the energy system can also become a site of political engagement in new ways. To understand energy citizenship in a digitalising grid, we argue for further empirical studies that examine how people interact with these tech­ nologies, how they handle the complexities of technologically mediated and automated collective actions, and how it spurs their imagination of alternatives. In other words, by focusing on everyday life, this perspective seeks to understand how people deal with distributed agency and responsibilities, when they feel frustrated or empowered, Declaration of competing interest The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Data availability The authors do not have permission to share data. References [1] T. Asad, On ritual and discipline in medieval Christian monasticism, Econ. Soc. 16 (2) (1987) 159–203. [2] S. Becker, M. Naumann, Energy democracy: mapping the debate on energy alternatives, Geogr. Compass 11 (8) (2017), e12321. [3] R. Belk, You are what you can access: sharing and collaborative consumption online, J. Bus. Res. 67 (8) (2014) 1595–1600. [4] M. Boekelo, S. Breukers, J. Young, R. Mourik, A just energy trading platform – or just an energy trading platform? ECEEE Summer Study Proc. (2022) 673–683. [5] J. Chilvers, N. Longhurst, Participation in transition (s): reconceiving public engagements in energy transitions as co-produced, emergent and diverse, J. Environ. Policy Plan. 18 (5) (2016) 585–607. [6] F. Ciulli, A. Kolk, Incumbents and business model innovation for the sharing economy: implications for sustainability, J. Clean. Prod. 214 (2019) 995–1010. [7] N. Crossley, 1 Ritual, Body Technique, and. Thinking Through Rituals: Philosophical Perspectives, 2004, p. 31. [8] P. Devine-Wright, Energy citizenship: psychological aspects of evolution in sustainable energy technologies, in: Governing Technology for Sustainability, Routledge, 2006, pp. 74–97. [9] A. Dobson, Citizenship and the Environment, OUP Oxford, 2003. [10] F. Friis, T.H. Christensen, The challenge of time shifting energy demand practices: insights from Denmark, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 19 (2016) 124–133. [11] R. Galvin, I’ll follow the sun: geo-sociotechnical constraints on prosumer households in Germany, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 65 (2020), 101455. [12] M. Hansen, B. Hauge, Scripting, control, and privacy in domestic smart grid technologies: insights from a Danish pilot study, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 25 (2017) 112–123. [13] T. Hargreaves, C. Wilson, R. Hauxwell-Baldwin, Learning to live in a smart home, Build. Res. Inf. 46 (1) (2018) 127–139. [14] E. Judson, O. Fitch-Roy, I. Soutar, Energy democracy: a digital future? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 91 (2022), 102732. 9 M. Boekelo and S. Kloppenburg Energy Research & Social Science 102 (2023) 103165 [34] R. Smale, S. Kloppenburg, Platforms in power: householder perspectives on the social, environmental and economic challenges of energy platforms, Sustainability 12 (2) (2020) 692. [35] R. Smale, G. Spaargaren, B. van Vliet, Householders co-managing energy systems: space for collaboration? Build. Res. Inf. 47 (5) (2019) 585–597. [36] R. Smale, B. Van Vliet, G. Spaargaren, When social practices meet smart grids: flexibility, grid management, and domestic consumption in the Netherlands, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 34 (2017) 132–140. [37] K. Standal, M. Talevi, H. Westskog, Engaging men and women in energy production in Norway and the United Kingdom: the significance of social practices and gender relations, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 60 (2020), 101338. [38] Y. Strengers, Smart Energy Technologies in Everyday Life: Smart Utopia? Springer, 2013. [39] K. Szulecki, Conceptualizing energy democracy, Environ. Polit. 27 (1) (2018) 21–41. [40] W. Throndsen, M. Ryghaug, Material participation and the smart grid: exploring different modes of articulation, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 9 (2015) 157–165. [41] V. Turner, D. Dewey, An essay in the anthropology of experience, Anthropol. Experience (1986) 33–44. [42] B. Turnheim, J. Wesseling, B. Truffer, H. Rohracher, L. Carvalho, C. Binder, Challenges ahead: understanding, assessing, anticipating and governing foreseeable societal tensions to support accelerated low-carbon transitions in Europe, in: Advancing Energy Policy, Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2018, pp. 145–161. [43] I. van de Poel, B. Taebi, Value change in energy systems, Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 47 (3) (2022) 371–379. [44] T. Van Der Schoor, B. Scholtens, Power to the people: local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy, Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 43 (2015) 666–675. [45] J. Van Dijck, T. Poell, M. De Waal, The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World, Oxford University Press, 2018. [46] L.F.M. Van Summeren, A.J. Wieczorek, G.P.J. Verbong, The merits of becoming smart: how Flemish and Dutch energy communities mobilise digital technology to enhance their agency in the energy transition, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 79 (2021), 102160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102160. [47] M. Wahlund, J. Palm, The role of energy democracy and energy citizenship for participatory energy transitions: a comprehensive review, in: Energy Research and Social Science Vol. 87, Elsevier Ltd., 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. erss.2021.102482. [48] G. Walker, N. Cass, Carbon reduction,‘the public’ and renewable energy: engaging with socio-technical configurations, Area 39 (4) (2007) 458–469. [49] G. Walker, P. Devine-Wright, Community renewable energy: what should it mean? Energy Policy 36 (2) (2008) 497–500. [50] T. Winther, H. Westskog, H. Sæle, Like having an electric car on the roof: domesticating PV solar panels in Norway, Energy Sustain. Dev. 47 (2018) 84–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2018.09.006. [51] M. Goulden, B. Bedwell, S. Rennick-Egglestone, T. Rodden, A. Spence, Smart grids, smart users? The role of the user in demand side management, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2 (2014) 21–29. [15] S. Kloppenburg, M. Boekelo, Digital platforms and the future of energy provisioning: promises and perils for the next phase of the energy transition, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 49 (2019) 68–73. [16] B.P. Koirala, E. Koliou, J. Friege, R.A. Hakvoort, P.M. Herder, Energetic communities for community energy: a review of key issues and trends shaping integrated community energy systems, Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 56 (2016) 722–744. [17] J. Markard, The next phase of the energy transition and its implications for research and policy, Nat. Energy 3 (8) (2018) 628–633. [18] N. Marres, Material Participation: Technology, the Environment and Everyday Publics, Springer, 2016. [19] M. Montakhabi, S. van der Graaf, M.A. Mustafa, Valuing the value: an affordances perspective on new models in the electricity market, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 96 (2023), 102902. [20] M. Montakhabi, S. van der Graaf, M.A. Mustafa, Valuing the value: an affordances perspective on new models in the electricity market, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 96 (2023), 102902. [21] D. Murillo, H. Buckland, E. Val, When the sharing economy becomes neoliberalism on steroids: unravelling the controversies, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 125 (2017) 66–76. [22] J. Naus, G. Spaargaren, B.J.M. van Vliet, H.M. Van der Horst, Smart grids, information flows and emerging domestic energy practices, Energy Policy 68 (2014) 436–446. [23] I.A. Niet, R. Dekker, R. van Est, Seeking public values of digital energy platforms, Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 47 (3) (2022) 380–403. [24] Y. Parag, B.K. Sovacool, Electricity market design for the prosumer era, Nat. Energy 1 (4) (2016) 1–6. [25] G. Powells, H. Bulkeley, S. Bell, E. Judson, Peak electricity demand and the flexibility of everyday life, Geoforum 55 (2014) 43–52. [26] G. Powells, M.J. Fell, Flexibility capital and flexibility justice in smart energy systems, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 54 (2019) 56–59. [27] H. Ransan-Cooper, H. Lovell, P. Watson, A. Harwood, V. Hann, Frustration, confusion and excitement: mixed emotional responses to new household solarbattery systems in Australia, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 70 (2020), 101656. [28] J. Roberts, Power to the people? Implications of the clean energy package for the role of community ownership in Europe’s energy transition, Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 29 (2) (2020) 232–244, https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12346. [29] K. Rommetveit, I.F. Ballo, S. Sareen, Extracting Users: Regimes of Engagement in Norwegian Smart Electricity Transition, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 2021 (01622439211052867). [30] M. Ryghaug, T.M. Skjølsvold, S. Heidenreich, Creating energy citizenship through material participation, Soc. Stud. Sci. 48 (2) (2018) 283–303. [31] J. Sadowski, A.M. Levenda, The anti-politics of smart energy regimes, Polit. Geogr. 81 (2020), 102202. [32] T. Scholz, N. Schneider, Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism, a New Vision for the Future of Work and a Fairer Internet, OR books, 2017. [33] A. Silvast, G. Valkenburg, Energy citizenship: a critical perspective, in: Energy Research and Social Science 98, Elsevier Ltd., 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. erss.2023.102995. 10