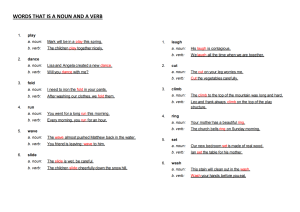

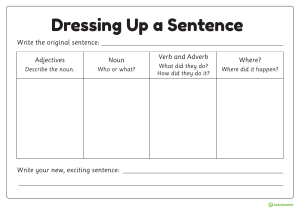

1. Grammar, its subject and parts. Relation of Grammar to other linguistic disciplines The term grammar is used to denote: 1) the objective laws governing the use of the word classes, their forms and their syntactic structures based upon their objective content; 2) the laws of a language as they are understood by a linguist or a group of linguists. Grammar is the study of rules governing the use of language. The set of rules governing a particular language is also called the grammar of the language; thus, each language can be said to have its own distinct granımar. Grammar is a part of the general study of language called linguistics. The sublevels of modern grammar are phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Traditional grammars include only morphology and syntax. There can also be differentiated several types of grammar. Thus, we may speak of a practical grammar and a theoretical grammar. A practical grammar is the system of rules explaining the meaning and use of words, word forms, and syntactic structures. A theoretical grammar treats the existing points of view on the content and use of words, word forms, syntactic structures and gives attempts to establish (if necessary) new ones. The main parts of grammar include: 1. Syntax: is another subdivision of grammar that deals with the structure of speech utterances that makes a sentence or a part of a sentence. 2. Morphology: is a part of grammar that treats meaning and use of classes of words - parts of speech as they are traditionally referred to. Morphology covers topics such as prefixes, suffixes, roots, and inflections. 3. Semantics: Semantics is the study of meaning in language. It involves understanding how words, phrases, and sentences convey meaning and how meaning is interpreted in different contexts. 4. Phonology: Phonology deals with the sound patterns of a language. It includes the study of phonemes, which are the distinct units of sound that differentiate words. Phonology explores how sounds are organized and patterned in a given language. Grammar is closely related to several other linguistic disciplines: Linguistics: Linguistics is the broader scientific study of language, and grammar is a fundamental component of linguistic analysis. Linguistics includes various subfields such as phonetics, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, and computational linguistics, each of which interacts with grammar in different ways. Syntax and Semantics: These are more specific branches of linguistics that focus on the structure of sentences and the meaning of linguistic expressions, respectively. Grammar plays a central role in both syntax and semantics. Pragmatics: Pragmatics studies how context influences the interpretation of meaning in communication. While grammar provides the structure of language, pragmatics examines how language is used in real-life situations, taking into account the social and cultural context. Stylistics: Stylistics is concerned with the expressive and artistic use of language. It examines how grammatical choices contribute to the style and tone of written or spoken discourse. Computational Linguistics: This field involves the application of computer science and artificial intelligence to the analysis and processing of natural language. Grammar is essential for developing computational models that can understand and generate human-like language. 2. General characteristics of auxiliaries for words Auxiliary verbs cannot exist by themselves in a sentence; they must be connected to another verb. These “helping” verbs can connect to both action and linking verbs in order to add tense, mood, voice, and modality to these verbs. Auxiliary verbs cannot stand alone in sentences; they have to be connected to a main verb to make sense. For example, a sentence that used the auxiliary verb, could, would also need a main verb for this helping verb to make sense. “She could not decide whether she wanted to dye her hair blue or purple.” The auxiliary verb helps the reader understand that the girl in the sentence was unable to make a decision. The main verb cannot express this indecision without the help of the auxiliary verb. Since auxiliary verbs help the main verb express tense, mood, and voice, there are three different kinds of auxiliary verbs to perform these three different functions. Auxiliary Verbs that Express Tense These auxiliary verbs can sometimes be confused with linking verbs, so it is important to use the context of the surrounding words in the sentence, or context clues, to know which verb is being used. For example: He was glad that he was wearing his seatbelt when the car accident happened. The first was links the subject, he, to a state of being, happy, so this is a linking verb. The second was is followed immediately by a main verb, wearing, so this is an auxiliary verb. The phrase was wearing is an example of a main verb paired with an auxiliary verb showing tense. This particular verb tense is called past progressive because it expresses an ongoing action that happened in the past. Auxiliary Verbs that Express Mood Oftentimes, auxiliary verbs that express mood are used in sentences that ask a question or sentences that make a command. Here is an example interrogative sentence, or a sentence that asks a question: Did you remember to feed the dog yesterday? Even though this auxiliary verb is separated from the main verb by the noun subject, it is still helping the main verb by asking whether something was done yesterday or not. Additionally, these auxiliary verbs can be used in commands, or imperative sentences. For example: Do not forget to walk the dog while I am at work! In this sentence, the auxiliary verb adds emphasis to the main verb showing that it is absolutely necessary to make sure that the dog is walked. Auxiliary Verbs that Express Voice Sometimes voice can refer to a writer’s specific style, but in this context, voice refers to the difference between active and passive voice. When a verb is written in active voice, the action is done by the subject of the sentence. For example: The lone dolphin called anxiously for his pod when he found himself surrounded by hungry orcas. In this sentence, the subject, dolphin, is performing the action of the sentence, which is called. However, if the voice was changed from active to passive, the subject could no longer do the action and it would look like this: The pod of dolphins was called by the anxious dolphin who was now surrounded by hungry orcas. The auxiliary verb, was, allows the writer to change the voice of the sentence from active to passive while keeping the same main verb. 3. English as an analytical language, its typological characterization All languages can be either analytical or synthetic. The modern English language is analytical. Analytical language is the language in which the predicative line is expressed with the help of conjunctions, prepositions and word order. The old English was synthetic. It means that the predicative line was expressed with the help of changing the forms of the words in the sentence. English is an analytical language, in which grammatical meaning in largely expressed through the use of additional words and by changes in word order. Ukrainian is a synthetic language, in which the majority of grammatical forms are created through changes in the structure of words, by means of a developed system of prefixes, suffixes and ending. Modern English is an analytic language, and non-inflected one, most of inflections died out within Middle English period. That means that word order is essential to the meaning of a sentence. If we want to emphasize something in a sentence, we use grammatical transformation to achieve this. Emphatic transformation is widely used to make new grammatical structures changing meaning of a sentence or to emphasize emotional color of an utterance. Being not native speakers of English, we can face misunderstanding in one or another grammatical transformation. On the contrary, some grammatical structures can seem for us suitable, while they are wrong, because we study English on the background of our native language. To be aware of right word order and acceptable ways to change the structure is very important for English study. A wrong way to use structural transformation of a sentence can cause curiosity and misunderstanding. The main features characterizing and analytical language are: 1. Comparatively few grammatical inflections 2. A sparing use of Sound alternations to denote grammatical forms. 3. A wide use of prepositions to denote relations between objects and connect words in the sentence. 4. Prominent use of word order to denote grammatical relations. So we may say that activization of analytical tendencies in different spheres of its grammar must not be ignored whenever one deals with the grammatical facts of English. 4. The notion of subjective and objective genitive. The use of objective genitive The difference between the subjective and objective genitive is important for languages, like Greek and Latin, in which the genitive or possessive case has multiple functions. But although little attention is paid to it in a language like English which has lost its nominal cases, this distinction is highly important also in it. The Objective Genitive is used with nouns, adjectives, and verbs. The objective genitive answers the question ‘of what?’ For example, ‘the child’ in ‘the experience of the child‘, if taken as an objective genitive, answers the question, ‘the experience of what?’. Here the child is the object of the experience. The subjective genitive, on the other hand, answers the question ‘whose?’, ‘belonging to whom?’ Hence, ‘the child’ in ‘the experience of the child‘, if taken as a subjective genitive, answers the question, ‘experience of whom?’, ‘whose experience?’ Here the child is the subject of the experience. A related distinction concerns what may be termed weak and strong ambiguity in the genitive. Weak ambiguity may be seen in a phrase like ‘the color of the sky’. Here there is little distinction between the objective and subjective senses of the genitive. ‘The color of what‘ seems to cover both. Presumably this is because the sky may be thought (rightly or wrongly) to exercise little subjectivity (pace William Turner). In contrast, in ‘the experience of the child’, the difference between the objective and subjective senses of the genitive is strong. Objectively there are a great many different possible experiences of a child. Subjectively, too, experience belonging to a child varies over a great range. As a result, definition in a phrase like ‘the experience of the child’ is much more demanding than it appears to be in a phrase like ‘the color of the sky’. The ambiguity of the genitive is stronger because the subjective aspect is marked. 5. Language type vs type of language. Synthetic and Analytical languages The type of the language is understood as a fixed set of main features of a language which are in definite relations with each other, and the presence or absence of one feature causes the presence or absence of another. The language type is understood as a fixed set of main features of a language which are in definite relations with each other irrelatively a concrete language. As far as the Indo-European languages are concerned, the two "language types" are commonly distinguished for their qualitative structural characterization: synthetic languages and analytical languages. Synthetic languages are defined as the languages of the "internal" grammar of the Word. Synthetic languages are inflectional languages because in such languages most grammatical meanings and most grammatical relations of the words are expressed with the help of inflectional devices, primarily. Analytical languages can be conventionally defined as the languages of the "external" grammar of the Word. The elements of synthesis and analysis are found in the languages of both the synthetic and the analytic order. It is a very common statement that Modern English is an analytical language as distinct from Slavonic languages which are synthetic. Human languages are not artificial static system. In the course of time different spheres of human language undergo certain changes. The historical changes human life and society are reflected in the systematics of the nominative units of the language vocabulary. Analytization has been stimulated by some internal conditions available within the Old English languages. Analytical tendencies in the Morphology of English are revealed in the spheres of Form-derivation systems. The main features characterizing and analytical language are: 1. Comparatively few grammatical inflections 2. A sparing use of Sound alternations to denote grammatical forms. 3. A wide use of prepositions to denote relations between objects and connect words in the sentence. 4. Prominent use of word order to denote grammatical relations. So we may say that activization of analytical tendencies in different spheres of its grammar must not be ignored whenever one deals with the grammatical facts of English. 6. Syntactical relations between the components of a phrase Syntactic relations of the phrase constituents are divided into two main types: agreement and government. By agreement we mean a method of expressing a syntactical relationship, which consists in making the subordinate word take a form similar to that of the word to which it is subordinate. In Modern English this can refer only to the category of number: a subordinate word agrees in number with its head word if it has different number forms at all.' This is practically found in two words only, the pronouns this and that, which agree in number with their head word. Since no other word, to whatever part of speech it may belong, agrees in number with its head word, these two pronouns stand quite apart in the Modern English syntactical system. As to the problem of agreement of the verb with the noun or pronoun denoting the subject of the action (a child plays, children play), this is a controversial problem. Usually it is treated as agreement of the predicate with the subject, that is, as a phenomenon of sentence structure. However, if we assume (as we have done that agreement and government belong to the phrase level, rather than to the sentence level, and that phrases of the pattern "noun + verb" do exist, we have to treat this problem in this chapter devoted to phrases. Thus, the sphere of agreement in Modern English is extremely small: it is restricted to two pronouns — this and that, which agree with their head word in number when they are used in front of it as the first components of a phrase of which the noun is the centre. By governmeat we understand the use of a certain form of the subordinate word required by its head word, but not coinciding with the form of the head word itself that is the difference between agreement and government. The role of government in Modern English is almost as insignificant as that of agreement. We do not find, in English any verbs, or nouns, or adjectives, requiring the subordinate noun to be in one case rather than in another. Nor do we find prepositions requiring anything of the kind. The only thing that may be termed government in Modern English is the use of the objective case of personal pronouns and of the pronoun who when they are subordinate to a verb or follow a preposition. Thus, for instance, the forms me, him, her, us, them, are required if the pronoun follows a verb (e. g. find or invite) or any preposition whatever. As to nouns, the notion of government may be said to have become quite uncertain in present-day English. Even if we stick to the view that father and father's are forms of the common amd the genitive case, respectively, we could not assert that a preposition always requires the form of the common case. For instance, the preposition at can be combined with both case forms: / looked at my father and / spent the summer at my father's, or, with the preposition to: I wrote to the chemist, and/ went to the chemist's, etc. It seems to follow that the notion of government does not apply to forms of nouns. 7. The prosess of analytization of the English language: analytical tendencies in morphology and syntax The Process of Analyzing the English Language: Analytical Tendencies in Morphology and Syntax The English language, like all languages, is a system of rules and patterns that govern how words are formed and how sentences are constructed. These rules and patterns, known as morphology and syntax, respectively, provide the framework for meaningful communication in English. Morphology Morphology is the study of the internal structure of words. It deals with how words are formed from smaller meaningful units called morphemes. Morphemes can be either root morphemes (the basic meaning-bearing units) or affixes (prefixes, suffixes, and infixes that attach to root morphemes to modify their meaning). English morphology exhibits a strong analytical tendency, meaning that words are typically composed of multiple morphemes that clearly convey their meaning. For instance, the word "unhappiness" is composed of the prefix "un-" (meaning "not"), the root morpheme "happy", and the suffix "-ness" (meaning "the state of being"). This clear breakdown of words into meaningful morphemes makes English morphology relatively transparent. Syntax Syntax is the study of how words are combined to form phrases and sentences. It deals with the rules that govern the order of words and the relationships between them. English syntax also exhibits analytical tendencies, meaning that the order of words is crucial for conveying meaning. For example, the sentence "The cat chased the mouse" clearly indicates that the cat is the agent of the action (the one doing the chasing) and the mouse is the patient (the one being chased). This clear order of subject-verb-object is a hallmark of English syntax. However, English syntax is not entirely rigid. It allows for some flexibility in word order, particularly in poetic or informal language. For instance, the sentence "The mouse was chased by the cat" is also grammatically correct, although it places the emphasis on the mouse rather than the cat. Analytical Tendencies in English Morphology and Syntax The analytical tendencies in English morphology and syntax have several implications for language learning and teaching. Implications for Language Learning The analytical nature of English morphology and syntax makes it a relatively transparent language to learn. Learners can easily identify the meaning of words by breaking them down into their constituent morphemes. Additionally, the clear word order rules in English syntax provide a predictable framework for constructing sentences. Implications for Language Teaching Teaching English morphology and syntax should emphasize the analytical nature of the language. Teachers can help learners identify morphemes and understand how they contribute to meaning. They can also focus on the importance of word order in English syntax. 8. The Adjective. The category of intensity and comparison. Substantive adjectives. Adjectives play a crucial role in providing more information about nouns (substantives) by describing their qualities or characteristics. Within the category of adjectives, there are various types, including those that indicate intensity and make comparisons. 1. Intensity Adjectives: Intensity adjectives convey the degree or level of a particular quality. They help provide a more nuanced description of the noun they modify. Examples of intensity adjectives include: - Very: e.g., a very tall building. - Extremely: e.g., an extremely hot day. - Incredibly: e.g., an incredibly fast car. 2. Comparative and Superlative Adjectives: Comparative adjectives are used to compare two things, while superlative adjectives are used to compare three or more things. Comparative Adjectives: - -er Ending: e.g., taller, faster. - More or Less: e.g., more beautiful, less crowded. - Irregular Forms: e.g., better, worse. Superlative Adjectives: - -est Ending: e.g., tallest, fastest. - Most or Least: e.g., most beautiful, least crowded. - Irregular Forms: e.g., best, worst. 3. Substantive Adjectives: Substantive adjectives are adjectives that function as nouns by themselves. They can without the need for an accompanying noun. For example: - The rich: Referring to wealthy people. - The elderly: Referring to older people. - The poor: Referring to people with financial challenges. These categories allow for a wide range of expression in the English language, enabling speakers and writers to convey specific details about the qualities, comparisons, and intensities of the nouns they describe. 9. Semiotic nature of human language. Linguistic units as a signs. The study of the semiotic nature of human language involves exploring how language functions as a system of signs. Semiotics is the study of signs and symbols, and it seeks to understand how meaning is created and communicated. In the context of language, linguistic units, such as words and sentences, are considered signs. Here are some key concepts related to the semiotic nature of human language: 1. Signs and Semiotics: - A sign is a basic unit of meaning. It consists of two components: - Signifier: The form of the sign, such as a word or a sound. - Signified: The concept or meaning associated with the signifier. 2. Saussurean Linguistics: - Ferdinand de Saussure, a linguist, contributed significantly to the study of semiotics and language. - He introduced the concepts of signifier and signified and emphasized the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign. In other words, the connection between the signifier and signified is not inherently logical; it is a matter of convention within a linguistic community. 3. Linguistic Units as Signs: - In language, various units function as signs. These include: - Phonemes: The smallest units of sound that can distinguish meaning. - Morphemes: The smallest units of meaning (e.g., prefixes, suffixes, roots). - Words: Combinations of morphemes that represent specific concepts. - Sentences: Combinations of words that convey meaning in a larger context. 4. Syntax and Semantics: - Syntax refers to the arrangement of words to create well-formed sentences. It deals with the structure of language. - Semantics is concerned with the meaning of linguistic units and how words and sentences convey meaning. 5. Pragmatics: - Pragmatics is the study of how context influences the interpretation of meaning. It considers the social and situational aspects of language use. 6. Cultural and Social Aspects: - Language is deeply embedded in culture and society. The meanings of signs are shaped by cultural conventions, and linguistic signs often carry social significance. 7. Signs and Communication: - Language is a fundamental tool for communication, and the study of signs helps us understand how communication occurs. Effective communication relies on shared conventions and an understanding of the meanings associated with signs. Understanding language as a system of signs provides insights into how meaning is constructed, shared, and interpreted within a linguistic community. The semiotic perspective helps linguists and scholars analyze the intricate relationship between language, thought, and culture. 10. The noun. The category of case in modern English. Divergent views on different kinds of cases. The noun in Modern English has only two grammatical categories: number and case. The Modern English noun has not got the category of gender and most languages Modern English distinguishes between two numbers: singular and plural. The meaning of the singular number shows that one object is meant and the plural shows that more than one objects are meant. The opposition is “one – more than one”. The category of number of English nouns is restricted in its realization by the implicit meaning of countableness/uncountableness. It is only realized in the subclass of countable nouns. The uncountable nouns do not fall under number, they do not decline in number. They have no categorial number forms. It is not fully justified to treat the “s” morpheme as plural ending. With words of pluralia tantum this “s” morpheme is likely to be identified as a suffix which function is to derive a new word. They work like plurals but they are not because they do not enter into oppositions. They have no singular opposites and the number opposition is neutralized. The form like waters is by no means, the categorial plural-number form. It is psevdo-plural form because the often water possesses the implicit meaning of uncountableness with which plurality is incompatible. The meaning of waters is not at all “much water”. The suffix “s” clerives a new word and has in the word waters the meaning of collectiveness. The waters of the Pacific Ocean Morpheme “s” with uncountable stems can express not only the collectiveness. With the stems of “mass noun” denoting material or substance this morpheme implies the “discreteness of fragments” as in ices, arts or “sort of” as in wines, oils, etc. such words as spectacles, ashes, customs and the like must not be mistaken for their homonyms which are plural forms. Their morphological structure is different and they have no singular opposites: N + stem + ending Spectacles – видовища Spectacle – видовище Ashes – ясені Ash – ясень N + stem + suffix Spectacles – окуляри Ashes – прах - The noun, as a fundamental part of speech, plays a crucial role in conveying meaning and constructing grammatical relationships within a sentence. One of the key categories relevant to nouns is case, which indicates the grammatical function of a noun in relation to other words. However, the nature and extent of case in modern English are subject to diverse viewpoints and ongoing debate among linguists. Here's a breakdown of the different perspectives: 1. Traditional View: This view proposes that modern English retains two grammatical cases: Nominative: This case marks the subject of a sentence (e.g., The boy runs). Genitive: This case marks possession (e.g., the boy's ball). The genitive case is formed by adding the apostrophe and "-s" to the noun (e.g., boy's, child's), or occasionally through periphrasis with "of the" (e.g., the king of the land). 2. Minimalist View: This perspective argues that modern English has lost its case system and only possesses vestiges of the previously richer system found in Old English. It proposes that the possessive "-'s" is not a true case marking but rather a derivational morpheme that creates possessive nouns. 3. Functionalist View: This approach focuses on the semantic and syntactic roles of nouns rather than relying solely on morphological markers. Proponents argue that modern English employs prepositions and word order to fulfill the functions traditionally attributed to case. For example, the preposition "of" often replaces the genitive case (e.g., the book of the king). 4. Divergent Views: Several linguists propose intermediate positions, recognizing some degree of case marking in modern English beyond the simple dichotomy of nominative and genitive. These include: Dative case: This case would mark the recipient of an action or the object indirectly affected (e.g., I gave the book to him). Locative case: This case would indicate the location of something (e.g., I am sitting at the table). Instrumental case: This case would mark the instrument used to perform an action (e.g., I wrote the letter with a pen). These additional cases are often marked through prepositions or word order, further complicating the analysis of case in modern English. The debate surrounding case in modern English reflects the dynamic nature of language and its tendency to evolve over time. While the traditional view remains common in introductory grammar instruction, the minimalist and functionalist perspectives offer alternative interpretations. Ultimately, understanding the different viewpoints and the ongoing research contributes to a richer and more nuanced understanding of this complex grammatical category. 11. Types of linguistic signs. Twofold nature of linguistics signs. Linguistic signs are symbols that are used to communicate. Written words are one type of linguistic sign. There are other types of linguistic signs, such as spoken words, gestures, and facial expressions. Linguistic signs can be divided into two categories: natural signs and conventional signs. Natural signs are those that occur naturally in the world, such as smoke rising from a fire. Conventional signs are those that are created by humans and agreed upon by a group of people, such as words in a language. Written words are linguistic signs that are created by humans and agreed upon by a group of people. They are symbols that are used to communicate. Written words can be divided into two categories: alphabetical writing and ideographic writing. Alphabetical writing is a system of writing in which each letter of the alphabet represents a different sound. Ideographic writing is a system of writing in which each character represents a different meaning. In the study of semiotics, which explores signs and symbols, linguistic signs are a fundamental concept. Linguistic signs have a twofold nature, consisting of two interrelated components: the signifier and the signified. These components work together to convey meaning. The types of linguistic signs can be categorized based on their characteristics. Let's explore these concepts: Types of Linguistic Signs: 1. Iconic Signs: 2. 3. Iconic signs have a resemblance or similarity to the object they represent. The connection between the signifier and the signified is based on visual or sensory similarity. Example: Onomatopoeic words like "buzz" or "moo" imitate the sounds they represent. Indexical Signs: Indexical signs establish a direct connection between the signifier and the signified through a causal or correlational relationship. Example: Smoke is an indexical sign of fire because the presence of smoke is caused by the presence of fire. Symbolic Signs: Symbolic signs rely on conventional, culturally agreed-upon associations between the signifier and the signified. The connection is arbitrary and established through social or linguistic conventions. Example: Most words in language, such as "dog" or "tree," are symbolic signs with arbitrary connections between the word and the concept it represents. Twofold Nature of Linguistic Signs: 1. Signifier: 2. Signified: The signifier is the physical form of the sign, whether it be a sound, written word, gesture, or image. It is the sensory aspect that we perceive. Example: In the word "cat," the arrangement of letters and the sound of the word are the signifiers. The signified is the mental concept or meaning associated with the signifier. It is the non-physical, cognitive aspect of the sign. Example: In the word "cat," the mental image or concept of a small, furry animal is the signified. Twofold Nature in Action: Example: Consider the word "tree." Signifier: The arrangement of letters and the sound of the word. Signified: The mental concept or image of a tall, woody plant with branches and leaves. Linguistic signs, with their twofold nature of signifier and signified, encompass iconic, indexical, and symbolic signs. The relationship between the signifier and signified can be based on resemblance, direct connection, or convention, reflecting the complexity and richness of communication in human language. 12. Different classification of adverbs. The category of state. Adverbs can be classified into different categories based on their functions and meanings. One way to categorize adverbs is by looking at their roles in describing different aspects of an action or state. Modern grammar follows traditional grammar in using meaning as a basis of adverb classification. But, since adverbs as a whole are so complicated there is no consensus as to the broad categories should be, beyond a general agreement that adverbs of time and frequency, adverbs of place, adverbs of manner, adverbs of degree, adverbs of probability and sentence adverbs form separate categories. Adverbs of time tell when something happens. I immediately waved at you. She saw you yesterday. She often swims in the sea. She never comes to my parties. Note that you do NOT use prepositions at, in or on with the time expressions: last year, last night, next Saturday, next week, the other day, the day after tomorrow. So, you are coming back next week? Common adverbs of time/frequency Afterward Eventually Late Once Then Weekly Again Finally Never Rarely Today Monthly Always First Now Seldom Tomorrow Yearly Before Forever Often Soon Usually Annually Normally Occasionally Hardly ever Frequently Yesterday The other day You can use prepositional phrases as adverbials of time: At is used with: Clock time: at five o’clock, at four fifteen; Religious festivals: at Christmas, at Easter; Mealtimes: at lunchtime, at breakfast; Specific periods: at night, at the weekend, at weekends, at half-term. In is used with: Seasons: in autumn, in the spring; Years and centuries: in 1963, in the year 2006, in the nineteenth century; Months: in January, in March; Parts of the day: in the morning, in the evenings. To say that something will happen during or after a period of time in the future: I think we’ll find out in the next few days. On is used with: Days: on Sunday, on Friday morning; Dates: on the sixth of January, on March 3rd. Special days: on Christmas day, on her birthday, on their wedding anniversary. You use for, NOT during to say how long something continues to happen. He is in Italy for a month. I remained silent for a long time. I will be in Brussels for three weeks. Adverbs of probability are used to say how sure you are about something: certainly, definitely, maybe, obviously, perhaps, possibly, probably, really. The driver probably knows the quickest route. I definitely saw her yesterday. You usually put adverbs of frequency and possibility before the main verb and after an auxiliary or a modal. He sometimes works downstairs in the kitchen. You are definitely wasting your time. He is always careful with his money. ‘Perhaps’ usually comes at the beginning of the sentence. Perhaps the beaches are cleaner in the north. Perhaps you need a membership card to get it. Adverbs of place tell where an action takes place. Some adverbs of place tell about position (locally), some tell about direction (left, upward), and most can tell about either direction or position (there, anywhere). A plane flew overhead. No birds or animals came near the body. She turned left at the corner. It was hot everywhere yesterday. Adverbs of degree tell to what degree or to what extent, you use them to modify verbs and adjectives. I totally disagree. I can nearly swim. Seaford is rather a pleasant town. My father gave me quite a large sum of money. When they are used with adjectives or other adverbs, they are sometimes called intensifiers. Rachel is running very fast. I definitely think she will win. She is really graceful. Mr Brooke strongly criticized the bank of England. That argument doesn’t convince me totally. The words in bold type in the following expressions are other common adverbs of degree: Absolutely lovely Otherwise happy Almost never Partly done Certainly charming Rather silly Greatly improved Scarcely tired Hardly ever Simply ridiculous However quickly So ugly Sad indeed Somewhat thirsty Only two Too expensive John is so interesting to talk to. Science is changing so rapidly. There was such a noise we couldn’t hear. They said such nasty things about you. I’ve been paying too much tax. Adverbs of manner tell how an action is done (move unwillingly) or the means by which an action is done (heated electrically). Adverbs of manner can also give information about adjectives (tragically short career). He talked so politely and danced so beautifully. She wanted to sit quietly, to relax. How By what means Treated badly Treated surgically Cooked professionally Cooked automatically Carefully polished Mechanically polished Some adverbs have the same form as adjectives and have similar meanings (fast, late, hard). I’ve always been interested in fast cars (adj). The man was driving too fast (adv). Note that hardly and lately have different meaning from the adjectives hard and late. It was a hard decision to make. I hardly had any time to talk to her. The train was late as usual. Have you seen John lately? Note that the adverb of manner related to the adjective good is well. He is a good dancer. He dances well. But well can be an adjective when it refers to someone’s health. 'How’re you?’ – ‘I’m very well, thank you.’ Sentence adverbs tell something about the entire sentence rather than about only a word in the sentence. Happily, the snow has melted. The roof leaks, unfortunately. Specifically, what is bothering him? Hopefully, everybody is ok. Unfortunatelly, he has missed his train. Some adverbs come in three forms: positive, comparative and superlative. A positive adverb modifies a verb, an adjective, another adverb, a clause, or an entire sentence but does not suggest comparison. Erica runs quickly. A comparative adverb compares two actions or conditions. Erica runs more quickly than I do. A superlative adverb compares three or more actions or conditions. Of all the members of the relay team, Erica runs the most quickly. These categories can overlap, and some adverbs may belong to more than one category depending on their context in a sentence. Adverbs play a crucial role in providing additional information about verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs, contributing to a more nuanced and detailed expression of language. 13. Referentiality of linguistic units and their denotative force. The concepts of "referentiality" and "denotative force" are related to how linguistic units, such as words or expressions, interact with the external world and convey meaning. Let's explore each concept: 1. Referentiality: - Definition: Referentiality refers to the ability of linguistic units to refer to, or be associated with, entities or concepts in the real world. - Example: In the sentence "The cat is on the mat," the words "cat" and "mat" are referential because they refer to actual objects in the real world. - Function: Referentiality is essential for communication, as it allows speakers to convey information about concrete or abstract entities. 2. Denotative Force: - Definition: Denotative force, also known as denotation, is the literal or primary meaning of a word or expression. It represents the objective reference to the real world. - Example: In the phrase "The sun rises in the east," the denotative force of "sun" is the actual celestial body that provides light and heat. - Function: Denotative force provides the basic, dictionary definition of a word and forms the foundation for communication. It helps establish a common understanding of the meaning of words. When considering both concepts together: - Relationship: Referentiality and denotative force are closely related because referentiality relies on the denotative force of words to establish connections between language and the external world. - Nuances: While denotative force deals with the literal meaning of words, referentiality extends to how language points to things, ideas, or experiences beyond the immediate linguistic context. Referentiality may also involve more abstract or indirect references. In communication, understanding both referentiality and denotative force is crucial for effective language use. However, it's important to note that linguistic units can also carry connotative meanings and be influenced by contextual factors, cultural nuances, and speaker intentions. 14. The system of English verb. The category of mood. The number of mood in English grammar Overview of the English Verb System The verb system of English is rather simple. Once you understand how all the tenses fit together, it is easy to choose the correct tense for the meaning you are trying to covey. The word tense refers to the form a verb takes, which is based on two things, Time Frame and Aspect: Time Frame tells whether a verb refers to now, or some particular time in the past or the future. Aspect tells how the verb is related to what time. There are four kinds of aspects, each one having its own basic meaning. Combining time frame and aspect creates 12 possible combinations of forms. These forms are tenses and the name of each tells which time frame and which aspect is being used: simple past tense, present perfect, future progressive and so on. Identifying the Basic Time Frame Uses of the three basic time frames in English vary. The different forms and uses are listed in the following charts. Use the Present Time Frame to talk about general relationships. Most scientific and technical writing is in present time. Anything that is related to the present moment is also expressed in present time, so newspaper headlines, news stories, spoken conversations, jokes and informal narratives are often in present time frame. Use the Past Time Frame to talk about things that are not directly connected to the present moment. Most fiction, historical accounts, and factual descriptions of past events are in past time frame. Use the Future Time Frame for anything that is scheduled to happen or predicted for the future. Identifying the correct time frame is the first step in deciding which tense to use. The second step is to choose from the tenses within the time frame. Verb is a part of speech with grammatical meaning of process, action. Verb performs the central role of the predicative function of the sentence. There are tree moods in English - the Indicative mood, the Imperative mood and the Subjunctive mood. The Indicative mood represents an action as a fact, as something real. (America was discovered in 1492). The Subjunctive Mood represents an action not as a real fact but as something that would take place under certain conditions, something desirable, necessary or unreal, unrealizable. There are 4 forms of the Subjunctive Mood in English: the Conditional Mood, the Suppositional Mood, Subjunctive1 and Subjunctive2. The Conditional Mood has 2 tenses: the present and the past. The Present Conditional is formed by means of the auxiliary verbs should and would and the Indefinite Infinitive of the main verb. The Present Conditional is used to express an action which would have taken place under certain conditions in the present and future. The Past Conditional is formed by means of the auxiliary verbs should and would and the Perfect Infinitive of the main verb. The Past Conditional is used to express an action which would have taken place under certain conditions in the past. Subjunctive2 has two tenses: the present and the past. The Present Subjunctive2 coincides in form with the Past Indefinite Indicative. The only exception is the verb to be the Present Subjunctive2 of which has the form were both in the plural and in the singular. The Past Subjunctive2 coincides in form with the Past Perfect Indicative. Subjunctive2 represents an action as contrary to reality. The Present subjunctive2 refers to the present and future. The Past Subjunctive2 refers to the past. Subjunctive1 coincides in form with the infinitive without the particle to. It has no tense distinctions- the same form may refer to the present, past and future. Suppositional Mood is formed by means of the auxiliary verb should and the infinitive of the main verb without the particle to. The Suppositional Mood has two tenses: the present and the past. Suppositional mood has two tenses: the present and the past. The Present Suppositional is formed by means of the auxiliary verb should and the indefinite infinitive of the main verb. The Past Suppositional is formed by means of the auxiliary verb should and the perfect infinitive of the main verb. Both the Suppositional Mood and Subjunctive1 are used to represent an action not as real fact but as something necessary, important, ordered, suggested, etc, and not contrary to reality. But the Suppositional Mood is much more widely used than Subjunctive1 in British English where Subjunctive1 is used in literary lan-ge in general. The Imperative mood expresses an order, a request, warning, invitation or a call to a joint action. Let's have a break. Note: The subject is sometimes used to make an order more emphatic. You go to bad at once! The Subjunctive mood represents an action not as a fact but as something imaginary or desired. If I had money now, I would buy his Opel. Якщо дуже скорочено In English grammar, the category of mood refers to the attitude or mode of the speaker towards the action or state expressed by the verb. There are three primary moods in English: indicative, imperative, and subjunctive. 1. Indicative Mood: - Definition: The indicative mood is used to make factual statements, ask questions, or express opinions. It is the most common mood in English. - Example: She is reading a book. Are you coming to the party? 2. Imperative Mood: - Definition: The imperative mood is used for giving commands, making requests, or offering invitations. The subject is often implied and may not be explicitly stated. - Example: Close the door. Please pass the salt. 3. Subjunctive Mood: - Definition: The subjunctive mood is used to express hypothetical or unreal situations, wishes, suggestions, and demands. It often appears in clauses following verbs like "wish," "suggest," "recommend," and in certain expressions. - Example: I wish she were here. It is important that he be on time. It's worth noting that the subjunctive mood is less distinct in modern English than in some other languages, and its usage is often context-dependent. In the present tense, the subjunctive form of the verb is often the same as the indicative form, except for the verb "to be" where "were" is used for all persons. The number of moods in English is three, as outlined above. Each mood serves a specific purpose in conveying the speaker's intention and the nature of the action or state described by the verb. 15. Functional grammatical studies: language as a functional system. Human language has two main jobs: one is to help us communicate, and the other is to express our thoughts. So, language is like a tool for sharing ideas with others. The expressive function of language is all about using words and signs to express ourselves. We call language a "semiotic system" because it uses signs that carry meaning. It's like a system of symbols that help us share information. Other examples of simpler sign systems include traffic lights, Morse code, the alphabet in sign language, and computer languages. The difference between language as a semiotic system and other semiotic systems is that the language is universal, natural, it is used by all members of society while any other sign systems are artificial and depend on the sphere of usage. 16. Modality and tense in Modern English. The meaning of the modal verbs. Modality is expression of speaker’s attitude to what his utterance denotes. The speaker may express various modal meanings. Modal verbs unlike other verbs, do not denote actions or states, but only show the attitude of the speaker towards the action. Modal verbs lack some regular verb forms, such as the third person singular -s in the present tense. They lack analytical forms and may lack a past tense form. 1. Usage Peculiarities: 2. Followed by the infinitive without "to" (except for ought, to have, and to be). Interrogative and negative forms are constructed without the auxiliary "do." Modal Verb Meanings: Can: Ability/Capability: E.g., "I can imagine how angry he is." Could used in the past or politeness (e.g., "He could speak English if necessary. Could I help you?"). Possibility: Permission: E.g., "You can take my umbrella." Uncertainty/Doubt: E.g., "You can see the forest through the other window." E.g., "Can it be true?" Improbability: E.g., "It can't be true." May: Supposition/Uncertainty: Possibility: E.g., "You may order a taxi by telephone." Permission: E.g., "He may be busy getting ready for his trip." E.g., "The director is alone now. So you may see him now." Disapproval/Reproach: E.g., "You might carry the parcel for me. You might have helped me." Must: Obligation: Prohibition: Emphatic Advice: E.g., "He must not leave his room for a while." E.g., "You must stop worrying about your son." Supposition/Probability: E.g., "Watson, we must look upon you as a man of letters." Should: Obligation/Advisability/Desirability: Supposition/Probability: 3. E.g., "The film should be very good as it is starring first-class actors." Usage in Reported Speech: 4. E.g., "You should go to bed." Must used in reported speech for past-time contexts. May, Might, Should Usage: Might used for past-time and as a milder form of may. Should used for present or future with meanings like obligation and supposition. This condensed overview emphasizes essential modal verb meanings and usage patterns. 17. Basic functions of language: the communicative and the expressive functions. There are two important functions of language: the communicative function and the expressive function. Communicative Function: Helps share information and make sure people understand each other. Examples: "The sun rises in the east." "Did you complete the assignment?" "Please pass me the salt." "What a beautiful sunset!" Expressive Function: Lets us show our feelings, emotions, or personal thoughts using words. Examples: "I am so excited about the upcoming trip!" "In my view, the new policy is ineffective." "I feel overwhelmed with joy on my birthday." "She spoke to me with such kindness." 18. Connective auxiliaries. Their regulatory and operatory functions. Connective auxiliaries are grammatical elements that connect different parts of a sentence or clauses. They often help to convey relationships between ideas or actions in a sentence. Examples: Words like "and," "but," "or," "however," "because," etc., are common connective auxiliaries. Regulatory Functions: Regulatory functions refer to the role that connective auxiliaries play in the structure of a sentence. They regulate how different elements are related and how they should be understood in context. Example: In the sentence "I like coffee, but my friend prefers tea," the connective auxiliary "but" regulates the relationship between the liking of coffee and the preference for tea, indicating a contrast. Operational Functions: Operational functions involve the practical effects or operations that connective auxiliaries have on the meaning of a sentence. They indicate semantic relationship between clauses or phrases. Example: In the sentence "She studied hard, so she passed the exam," the connective auxiliary "so" operates to show a cause-and-effect relationship between studying hard and passing the exam. 19. Systemic view upon language: language as a system. Language is the system, phonological, lexical, and grammatical, which lies at the base of all speaking. Speech is the manifestation of language or its use by speakers, writers of the given language. The elements of the plain “language” are given by their generalized forms. But they don’t exist if not concreticized. Human language exists through its speech manifestation. Language is the most important form of human communication. Certainly, language is human only. Insects, birds as well as man do communicate but they don’t talk. And language is a form and means of communication. There are some ways of looking at language. 1. 2. 3. Language is a form of order, a pattern, a code. Language is first and foremost means of sharing information. And its studies symbols and signs that they symbolize. Language is made up of messages produced in such a way as to be decoded word-by-word. Language is also a form of social behavior. 20. The system of the English verb. The category of voice. Some peculiarities of the Passive Voice in Modern English. The form-derivation of English verbs is highly developed. There are about 18 forms in the verb paradigm and most of them are analytic formation. The main verbal categories constitute finiteness of the predicate. These are Tense and mood which are commonly recognized to be basic. They are morphologico- syntactical due to their predicative character. Tense and Mood find their realization only in the form-derivation of the finite verb, they are the main categories of the verb. Verb-forms of different categorial status: 1) 2) 6) 7) Tense forms: Present, Past, Future Aspect-tense forms: Present Continuous, Past Continuous, Future Continuous, Present Perfect Continuous, Past Perfect Continuous Perfect – tense forms: Present Perfect, Past Perfect, Future Perfect, Present Perfect Continuous, Past Perfect Continuous. Voice-tense forms: Present Passive, Past Passive, Future Passive Aspect-voice-tense forms: Present Continuous Passive Past Continuous Passive Mood forms: Imperative, Indicative, Subjunctive Mood-perfect forms: Perfect-Subjunctive Voice in grammar expresses the relationship between the subject and the action of the verb. 3) 4) 5) Modern English has two voices: active and passive. The active voice indicates the subject as the doer of the action, while the passive voice highlights the subject as the receiver of the action. In passive constructions, the doer may be unknown or omitted. For instance: 1. Active voice: The teacher asked the pupil. 2. Passive voice: The teacher was asked by the pupil. Some grammarians hold that the number of voices is more than two. Some of them count even five voices in Modern English, namely: the Active voice, the Passive voice, the Reflexive voice, the Middle voice, and the Reciprocal voice. They saw each other onlv for a moment. (the Reciprocal voice.) 21. Structural view upon language: peculiarities of language structure. The language structure looks the following: 1. Phonetics, Phonology (sounds): Phonetics: Studies all human sounds. Phonology: Looks at specific sounds in a language and how they create meaning. Examples: "Cat" and "bat" sound different, changing the meaning. The "th" sound in "think" and "this”; the pronunciation of vowels in "cot" and "caught." 2. Morphology and Lexicology (words and endings): Morphology: Explores word forms and endings. 3. Lexicology: Checks out word structure. Examples: "Running" shows the action, and "runner" is the person doing it; "care" and "careless." Syntax and Language Typology (senrences): Syntax: Focuses on arranging words to create sentences. Language Typology: Sorts languages based on shared rules. Examples: "The cat chased the mouse" has a different meaning than "The mouse chased the cat." "The dog chased the cat" vs. "The cat chased the dog." 4. Semantics (meaning) : Examines word, sentence, and overall language meanings. Examples: "Home" means a place where someone lives. "fast car" and "fast runner"; "old friend" and "old book." 5. Pragmatics (practical use) : Deals with how we use language in real situations. Examples: Saying "Can you pass the salt?" at the dinner table. "Could you close the door?" 6. Syntagmatic Relations in Grammar (Word Relationships): Looks at how words connect in a sequence. Examples: "She sang a song" - the words work together to convey meaning. "The big elephant," where "big" describes the noun "elephant." "She walked slowly," where "slowly" modifies the verb "walked." 7. Paradigmatic Relations (Word Substitutes) : Shows how words can replace each other. Examples: "Hot" can be replaced by "warm" in "The coffee is hot." "angry" for "mad; "happy" with "joyful"; "eat" to "ate" or "eating"; "my" for "your". In short, linguistics studies sounds, words, sentences, meaning, practical use, and word relationships. Syntagmatic relations focus on word sequences, while paradigmatic relations involve words that can substitute for each other. 22. Peculiarities of function-words in the text In English grammar, a function word is a word that expresses a grammatical or structural relationship with other words in a sentence. In contrast to a content word, a function word has little or no meaningful content. Nonetheless, as Ammon Shea points out, "the fact that a word does not have a readily identifiable meaning does not mean that it serves no purpose." Function words are also known as: structure words grammatical words grammatical functors grammatical morphemes function morphemes form words empty words Function words include determiners, conjunctions, prepositions, pronouns, auxiliary verbs, modals, qualifiers, and question words. Function words include: the (determiner) over (preposition) and (conjunction) Even though the function words don't have concrete meanings, sentences would make a lot less sense without them. Determiners Determiners are words such as articles (the, a), possessive pronouns (their, your), quantifiers (much), demonstratives (that, those), and numbers. They function as adjectives to modify nouns and go in front of a noun to show the reader whether the noun is specific or general, such as in "that coat" (specific) vs. "a coat" (general). Articles: a, an, the Demonstratives: that, this, those, these Possessive pronouns: my, your, their, our, ours, whose, his, hers, its, which Quantifiers: some, both, most, many, a few, a lot of, any, much, a little, enough, several, none, all Conjunctions Conjunctions connect parts of a sentence, such as items in a list, two separate sentences, or clauses and phrases to a sentence. In the previous sentence, the conjunctions are or and and. Conjunctions: and, but, for, yet, neither, or, so, when, although, however, as, because, before Prepositions Prepositions begin prepositional phrases, which contain nouns and other modifiers. Prepositions function to give more information about nouns. In the phrase "the river that flows through the woods." The prepositional phrase is "through the woods," and the preposition is "through." Prepositions: in, of, between, on, with, by, at, without, through, over, across, around, into, within Pronouns Pronouns are words that stand in for nouns. Their antecedent needs to be clear, or your reader will be confused. Take "It's so difficult" as an example. Without context, the reader has no idea what "it" refers to. In context, "Oh my gosh, this grammar lesson," he said. "It's so difficult," the reader easily knows that it refers to the lesson, which is its noun antecedent. Pronouns: she, they, he, it, him, her, you, me, anybody, somebody, someone, anyone Auxiliary Verbs Auxiliary verbs are also called helping verbs. They pair with a main verb to change tense, such as when you want to express something in present continuous tense (I am walking), past perfect tense (I had walked), or future tense (I am going to walk there). Auxiliary verbs: be, is, am, are, have, has, do, does, did, get, got, was, were Modals Modal verbs express condition or possibility. It's not certain that something is going to happen, but it might. For example, in "If I could have gone with you, I would have," modal verbs include could and would. Modals: may, might, can, could, will, would, shall, should Qualifiers Qualifiers function like adverbs and show the degree of an adjective or verb, but they have no real meaning themselves. In the sample sentence, "I thought that somewhat new dish was pretty darn delicious," the qualifiers are somewhat and pretty. Qualifiers: very, really, quite, somewhat, rather, too, pretty (much) Question Words It's easy to guess what function that question words have in English. Besides forming questions, they can also appear in statements, such as in "I don't know how in the world that happened," where the question word is how. Question words: how, where, what, when, why, who 23. Morpheme, the definition of morpheme A "morpheme" is a short segment of language that meets three basic criteria: 1. It is a word or a part of a word that has meaning. 2. It cannot be divided into smaller meaningful segments without changing its meaning or leaving a meaningless remainder. 3. It has relatively the same stable meaning in different verbal environments. додатково про морфеми дивися в питання 25. 24. The system of English verb. The notion of time and grammatical category of tense. O. Jespersen’s scheme of time and tenses The English verb system is an essential component of the language that conveys actions, events, or states of being. English verbs undergo various changes to indicate tense, aspect, mood, voice, and agreement with the subject. Here are some key aspects of the English verb system: Tense: Present Tense: Describes actions happening now or general truths. "I walk to school every day." Past Tense: Describes actions completed in the past. "She played the piano yesterday." Future Tense: Describes actions that will happen in the future. "They will arrive tomorrow." Aspect: Simple Aspect: Describes actions without focusing on their duration or completion. "He writes a letter." Progressive (Continuous) Aspect: Describes actions that are ongoing or in progress. "She is reading a book." Perfect Aspect: Indicates the completion of an action before a certain point in time. "I have finished my homework." Mood: Indicative Mood: Used for statements, facts, or questions. "He is going to the store." Imperative Mood: Gives commands or makes requests. "Please close the door." Subjunctive Mood: Expresses hypothetical situations, wishes, or suggestions. "If I were you, I would go." Voice: Active Voice: The subject performs the action. "The cat chased the mouse." Passive Voice: The subject receives the action. "The mouse was chased by the cat." Infinitives, Gerunds, and Participles: Infinitive: The base form of the verb (e.g., "to walk"). Gerund: The -ing form of the verb used as a noun (e.g., "Walking is good for health."). Participle: Verb forms used in various constructions (e.g., "She has walked a long way."). Otto Jespersen’s classification He distinguishes main or simple times (Present and Past), subordinate times which are points in time posterior or anterior to some other point (in the present, in the past or in the future). This is a logical scheme (the before past time, the after past time, the before future time, the after future time), with no simple future (She gave birth to a son who was to cause her great anxiety (the after past). He excluded the future on the ground that in English there are no grammatical means to express pure futurity, the “so called future” being modal. 25. Types of morphemes There are two primary types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes. FREE MORPHEMES A free morpheme can carry semantic meaning on its own and does not require a prefix or suffix to give it meaning. In other words, it can stand on its own as a word, like the, boy, run, and luck. Each of these morphemes can function independently. BOUND MORPHEMES Bound morphemes cannot stand alone but must be bound to other morphemes, like –s, un-, and –y. Bound morphemes are often affixes. This is a general term that comprises prefixes, which are added to the beginnings of words, like re– and un-, and suffixes, which are added to the ends of words, like –s, –ly, and –ness. Some languages also have infixes, which are added into the middle of words, but these are rare in Modern English. Bound morphemes are further divided into two subtypes: derivational and inflectional morphemes. Derivational morphemes change the meaning or the part of speech of a word (i.e., they are morphemes by which we “derive” a new word). Examples are un-, which gives a negative meaning to the word it is added to, –y, which turns nouns into adjectives, or –ness, which turns adjectives into nouns. Inflectional morphemes add grammatical information to the word, such as –s on runs, which tells us that it is 3rd person singular present tense verb, or the –s on boys, which tells us that there is more than one boy. There are eight inflectional suffixes, often just called “inflections,”” in English: -s on verbs: 3rd person sg, present tense (he runs, she walks) -ed on verbs: past tense: (I walked, they joined) -ing on verbs: progressive (I was walking; they were joining) -en on verbs: past participle (I was beaten; she has eaten) -s on nouns: plural (boys, books) -’s on nouns; possessive (boy’s, book’s) -er on adjectives: comparative (quicker, slower) -est on adjectives: superlative (quickest) CONTENT VS FUNCTION MORPHEMES There is one final distinction between different kinds of morphemes: Content morphemes, which have a clear semantic meaning (like book, luck, un-, –y, boy) Function morphemes, which include all inflectional morphemes like –s, and –ed, but also include free morphemes such as the, of, with, and, but, and other similar words. These words signify the grammatical relationships between words and give structure to a sentence. ALLOMORPHS Allomorphs are non-meaningful variants of a morpheme. For example, the -s plural takes three distinct phonological forms, [s], [z], and [ɪz], in the words boys [bɔɪz], books [bʊks], and dishes [dɪʃɪz]. These phonological distinctions are considered non-meaningful, making these allomorphs of the -s plural morpheme. (можливо спитає) 26. Classification of adverbs according to their structure According to their morphological structure adverbs are classified into 1) simple, 2) derivative, 3) compound, 4) complex. Simple adverbs are devoid of affixes and consist of a root-stem: enough, back, here, there, then, quite, well, rather, too. Derivative adverbs are formed by means of suffixes. The most productive adverb-forming suffix added to adjectives is -ly. For example: slowly, widely, beautifully, heavily, easily, lazily, differently, simply, etc. There are also -ward/-wards suffixes: northward/ northwards, southward/southwards, earthward/earthwards, downward/downwards. Compound adverbs are made up of two stems: anywhere, anyway, anyhow, sometimes, somehow, nowhere, clockwise, likewise, longwise. Complex adverbs include prepositional phrases like at a loss, at work, by name, by chance, by train, in debt, in a hurry, in turn, etc. 27. The Numeral as the part of speech Numerals are an independent part of speech that indicates the number of objects or their order. In an English sentence, numerals act as a designation or nominal part of a complex predicate, because in English they are often called quantitative adjectives. Numerals of the English language are divided into quantitative and ordinal numerals. Сardinal numerals Сardinal numbers indicate the number of living beings, objects, phenomena. They answer the question " how much?" 1- one 2- two When using the words hundred, thousands, millions, etc. in numbers , the ending -s is not added to such numerals , which indicates the plural. The ending -s is used when these numerals act as nouns that do not indicate a specific number of objects, for example, in the phrases dozens, hundreds of, thousands of . E.g I bought twelve eggs. I hope it will be enough Ordinal numerals Ordinal numerals indicate the order of objects, their serial number. They answer the question " which one?" ". Most ordinal numerals are formed from quantitative ones with the help of the ending -th. 1 – first 2 - second 3 - third 4 – fourth Nouns preceded by ordinal numerals are used with the definite article the. E.g. The tenth candy was too much for me. 28. Types of word form derivation (synthetic and analytical) These types devide into two main parts: 1)those limited to changes in the body of the word, without having recourse to auxiliary words (synthetic types). 2) those implying the use of auxiliary words (analytical types) Besides there are some special cases of different forms of a word being derived from altogether different stems Synthetic Types The number of morphemes used for deriving word forms in Modem English is very small. There is the inflection-s (-es), with three variants of pronunciation, used to form the plural of almost all nouns, and the ending-en and-ren, used for the same purpose (oxen, children). For the adjectives, there are the endings-er, and-est for the degrees of comparison. There is the ending-s (-es) for the third person singular present indicative, the ending-d-ed) for the past tense of certain verbs: the -d (-ed) for the second participle of certain verbs, the ending- (n-en) for the second participle and ending-ing for Participle 1 and also for the gerund. Thus the total number of morphemes used to derive forms of words a eleven or twelve, which is much less than the number found in languages of a mainly synthetical structure. Analytical Types These consist in using a word to express some grammatical category of another word. Let’s consider such combinations as have done, is done, is doing, doesn't do. The verbs have, be, does have no lexical meaning of their own in these cases. Such verbs as have, be, do, shall, will are called auxiliary verbs. They constitute a typical feature of the analytical structure of Modern English 29. The clauses , their characteristic features Clauses are grammatical structures that contain a subject and a predicate. They are the building blocks of sentences and can be classified into different types based on their functions and structures. Here are some key types of clauses and their characteristic features: 1. Independent Clauses: o Definition: An independent clause is a complete sentence on its own. It expresses a complete thought and can stand alone. o Example: "I went to the store." 2. Dependent (Subordinate) Clauses: o Definition: A dependent clause cannot stand alone as a complete sentence. It depends on an independent clause to form a complete thought. o Example: "Although I was tired, I went to the store." (The dependent clause "Although I was tired" cannot stand alone; it needs the independent clause "I went to the store" to complete the thought.) 3. Relative Clauses: o Definition: A relative clause provides additional information about a noun in the sentence. It usually begins with a relative pronoun (who, whom, whose, which, that). o Example: "The book that I bought is on the table." 4. Adjective Clauses: o Definition: An adjective clause functions like an adjective, providing more information about a noun in the sentence. o Example: "The man who is wearing a hat is my neighbor." 5. Adverbial Clauses: o Definition: An adverbial clause functions as an adverb, modifying a verb, adjective, or another adverb. It often answers questions such as when, where, why, how, etc. o Example: "Since it was raining, we stayed indoors." 6. Noun Clauses: o Definition: A noun clause functions as a noun within a sentence. It can act as the subject, object, or complement. o Example: "What she said surprised me." (The noun clause "What she said" functions as the direct object.) 7. Conditional Clauses: o Definition: Conditional clauses express a condition and its result. They often begin with words like "if," "unless," "when," etc. o Example: "If it rains, we will stay at home." 8. Coordinate Clauses: o Definition: Coordinate clauses are independent clauses connected by coordinating conjunctions (and, but, or, nor, for, yet, so). o Example: "I like coffee, but my sister prefers tea." Understanding the different types of clauses and their functions is essential for constructing clear and grammatically correct sentences. 30.Main parts of the sentence A sentence is typically composed of two main parts: the subject and the predicate. These parts work together to convey a complete thought. Here's an overview of each: Subject: 1. Simple Subject: o Definition: The simple subject is the main noun or pronoun within the subject, excluding any modifiers. o Example: In the sentence "The big, brown dog barked loudly," the simple subject is "dog." 2. Complete Subject: o Definition: The complete subject includes the simple subject along with all its modifiers. o Example: In the same sentence, "The big, brown dog barked loudly," the complete subject is "The big, brown dog." 3. Implied Subject: o Definition: In imperative sentences, the subject is often implied (understood but not explicitly stated). o Example: "Close the door." (The implied subject is "you.") Predicate: 1. Simple Predicate (Verb): o o 2. Definition: The simple predicate is the main verb or verb phrase that tells what the subject is doing. Example: In the sentence "She is reading a book," the simple predicate is "is reading." CompletePredicate: o Definition: The complete predicate includes the simple predicate along with all its modifiers and objects. o Example: In the same sentence, "She is reading a book," the complete predicate is "is reading a book." 3. Compound Predicate: o Definition: A compound predicate consists of two or more verbs or verb phrases that share the same subject. Example: "She laughed and danced at the party." (The compound predicate is "laughed and danced.") In addition to the subject and predicate, sentences may also contain other elements that provide additional information. These include: 3. Object: o Direct Object: The noun or pronoun that receives the action of the verb directly. Example: "the ball" in the sentence "She threw the ball." o Indirect Object: The noun or pronoun that benefits from the action of the verb. Example: "her" in the sentence "She gave her a book." 4. Complement: o Predicate Nominative (PN): A noun or pronoun that follows a linking verb and renames or identifies the subject. Example: "My brother is a doctor." (Here, "a doctor" is the predicate nominative.) o Predicate Adjective (PA): An adjective that follows a linking verb and describes the subject. 5. Example: "The soup is delicious." (Here, "delicious" is the predicate adjective.) Modifiers: o Adjectives: Words that modify or describe nouns. Example: "The tall man is my brother." o Adverbs: Words that modify or describe verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. Example: "He ran quickly to catch the bus." 31.Hypotactic relations in noun-phrase Hypotactic relations involve the use of subordination structures in language. It relates to a grammatical structure that contains a dependent clause (= a clause that cannot form a separate sentence but can form a sentence when joined with a main clause). In the context of noun phrases, this often means using modifiers and complements to provide additional information about the main noun in a subordinate manner. Here are a few examples: 1. o 2. o 3. o Modifiers in Hypotactic Noun Phrases: Modifiers like adjectives can be hierarchically arranged to describe the noun. Example: The tall, ancient tree stood in the park. In this case, "tall" and "ancient" are modifiers that hierarchically relate to the main noun "tree." Prepositional Phrases as Complements: Complements, such as prepositional phrases, can be used in a hypotactic manner. Example: The girl with the blue dress is my sister. Here, the prepositional phrase "with the blue dress" complements and provides additional information about the noun "girl." Relative Clauses in Hypotactic Noun Phrases: Relative clauses also create hypotactic structures by adding information to the noun. Example: The car that was parked on the street is mine. The relative clause "that was parked on the street" provides additional details about the noun "car." 32.Functional peculiarities of the different kinds of pro-units. Pronominals are as pro-units that replace nominals (N-elements) in the context of English linguistics. Let's break this down: 1. o 2. o 3. o o 4. o Pronominals: Pronominals are linguistic elements that function like pronouns. In English, pronouns are words that can replace nouns (nominals) to avoid repetition and add variety to language. N-elements: In linguistic terms, N-elements typically refer to nominal elements, which include nouns and noun phrases. Nominals are words or groups of words that function as nouns. Pro-units replacing N-elements: Pronominals, or pro-units, play a crucial role in replacing nominals to avoid redundancy and enhance the flow of language. They serve as substitutes for nouns or noun phrases. Examples: Noun: The cat is on the table. Pronominal: It is on the table. Types of Pronominals in English: Personal Pronouns: Replace specific persons or things. Examples: I, you, he, she, it, we, they. o o o o o Demonstrative Pronouns: Point to specific things. Examples: this, that, these, those. Possessive Pronouns: Indicate ownership or possession. Examples: mine, yours, his, hers, its, ours, theirs. Relative Pronouns: Introduce relative clauses and connect them to the main clause. Examples: who, whom, whose, which, that. Interrogative Pronouns: Used to ask questions. Examples: who, whom, whose, which, what. Indefinite Pronouns: Refer to non-specific people or things. Examples: all, some, none, any, anyone, everyone, no one, somebody, nobody, something, anything. In English, these pronominals serve as pro-units by replacing or standing in for nominal elements, contributing to the efficiency and variety of expression in language. Their usage follows grammatical rules and depends on factors such as person, number, and gender. .33. The word as a language unit and its linguistic status The word is a fundamental unit of language, and its linguistic status is important in the study of linguistics. Here are key aspects of the word as a language unit: 1. Definition and Morphology: A word is a basic unit of language that carries meaning.(so it's nominative unit). A word is a unit of speech which serves the purposes of human communication. o Morphology, the study of word structure, analyzes how words are formed from smaller units called morphemes. Morphemes are the smallest units of meaning and can be free (stand alone) or bound (require attachment to other morphemes). 2. Phonological Aspect: o Words have a phonological aspect related to their pronunciation. Phonology is the study of the sound patterns and rules in a language, including the way sounds combine to form words. 3. Semantic Content: o Words convey meaning, and their semantic content is central to understanding language. Words can represent concrete objects (e.g., "tree"), actions (e.g., "run"), qualities (e.g., "beautiful"), and more. 4. Syntactic Role: o In syntax, the study of sentence structure, words function as parts of speech and play specific roles within sentences. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and other parts of speech contribute to the overall structure and meaning of sentences. 5. Lexical Units: o Words are the basic building blocks of a language's vocabulary. Lexicons or dictionaries catalog words along with their meanings, providing a comprehensive record of a language's lexical units. 6. Function Words vs. Content Words: o Function words (e.g., articles, prepositions, conjunctions) serve grammatical functions, while content words (e.g., nouns, verbs, adjectives) carry more specific meaning. This distinction is crucial for understanding how words contribute to the structure of a sentence. 7. Word Classes or Parts of Speech: o Words can be categorized into different classes or parts of speech based on their syntactic and semantic roles. Common parts of speech include nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions. 8. Orthography: Orthography deals with the correct writing and spelling of words. While not a linguistic feature per se, the written representation of words is an important aspect o of language. 34.Genaral characteristics of functional words. Function words are words that have a grammatical purpose. Function words are small words in a language that help put sentences together and show how words relate to each other. They are not the main words that carry the meaning (like nouns or verbs), but they are important for making sentences clear and grammatically correct. Here are some common types of function words: 1. Articles: Examples: "a," "an," "the" Function: Indicate the definiteness or indefiniteness of a noun. 2. Prepositions: o Examples: "in," "on," "at," "by," "with" o o o Function: Show relationships in space and time, often indicating location or direction. Conjunctions: o Examples: "and," "but," "or," "if," "because" o Function: Connect words, phrases, or clauses within a sentence. 4. Pronouns: o Examples: "I," "you," "he," "she," "it," "we," "they" o Function: Replace nouns to avoid repetition and refer to specific entities. 5. Auxiliary Verbs: o Examples: "is," "have," "will," "can," "may" o Function: Combine with main verbs to indicate tense, aspect, mood, or voice. 6. Modal Verbs: o Examples: "can," "could," "will," "would," "may," "might," "shall," "should" o Function: Express possibility, necessity, permission, or ability. 7. Adpositions: o Examples: "above," "below," "between," "through," "against" o Function: Express relationships, often spatial or temporal, between elements in a sentence. 8. Determiners: o Examples: "this," "these," "those," "some," "many" o Function: Provide information about the noun they modify, such as quantity or proximity. 9. Interjections: o Examples: "oh," "wow," "ouch," "hey" o Function: Express emotions or reactions and often stand alone as exclamations. 10. Particles: o Examples: "up," "down," "out," "off" Function: Modify verbs or adjectives to convey direction or intensity. 3. 35.The Word as a linguistic sign: its bilateral nature. [Note: by bilateral they mean with two-sides nature.] Word Structure: A word has a dual nature: material (heard or seen) and immaterial (meaning). Forms (written and oral) represent the material aspects, while meanings represent the immaterial. A word consists of at least one lexical morpheme, along with potential grammatical and lexico-grammatical morphemes. Lexical morphemes Lexical morphemes, like "book-," have more independent and specific meanings. For example, a word like "books" consists of two morphemes (meaningful parts) such as "book-" which is a lexical morpheme and "-s," which is a grammatical morpheme. Grammatical Morphemes: Morphemes like "-s" and "-ed" have relative, dependent, and indirect meanings, termed grammatical meanings. For example: words "Invites" and "shall invite" share the lexical morpheme "invite-" but differ in grammatical morphemes (-s and "shall"). - "Invites" (with bound morphemes “-s”) is a synthetic word. - "Shall invite" (with free morphemes “shall”) is an analytical word. Lexico-Grammatical Morphemes: Morphemes like "de-," "for-," "-er," "-less" are lexico-grammatical morphemes. They are bound, attached to specific lexical morphemes, and determine lexical meanings. For example, synthetic word “worker” has two lexico-grammatical morphemes “work-” and “-er” (the morpheme “-er” gives the root word “work” new meaning of profession (робота-робітник)) For example: words "Stand up," "give in," and "find out" resemble analytical words but differ from each other. "Shall" in "shall give" doesn't introduce lexical meaning, while morpheme "out" in "find out" does. "Out" is an example of a lexico-grammatical word morpheme. Prefixes vs. Suffixes: Lexical morpheme is the root, and affixes (prefixes, suffixes, infixes) are bound morphemes. Suffixes are more significant in grammatical structure than prefixes. Suffixes include both grammatical and lexico-grammatical morphemes, while prefixes are mainly lexico-grammatical. Stems: Words without grammatical morphemes, often called stems, come in four types: 1. Simple: Containing only the root (e.g., day, dogs). 2. Derivative: Containing affixes or other stem-building elements (e.g., boyhood, rewrite). 3. Compound: Containing two or more roots (e.g., white-wash, pickpocket). 4. Composite: Containing free lexico-grammatical word-morphemes or resembling a combination of words (e.g., give up, two hundred and twentyfive). 36. The sentence and its definitions. Numerous classifications of the sentence A sentence is like a complete thought in words. It has a specific structure and helps us communicate. Propositional Aspect: Sentences tell us something that can be true or false. They give information. Structural Aspect: A sentence has parts - a subject and a predicate. It follows a specific word order. Phonological Aspect: When we speak, a sentence is the words we say between pauses. Key Features of Sentences: Integrity: It's a complete thought. Syntactic Independence: It makes sense on its own, following grammar rules. Grammatical Completeness: It follows language rules correctly. Semantic Completeness: It fully conveys meaning. Communicative Completeness: It can stand alone in communication. Communicative Functioning: It serves a purpose in communication. Predicativity: It often makes a statement or expresses an action. Modality: It can show mood or certainty. Intonational Completeness: It sounds natural when spoken. Types of Sentences: Declarative: States facts. "The sun rises in the east." Exclamatory: Shows strong feelings. "What a beautiful sunset!" Imperative: Gives commands. "Close the door." Interrogative: Asks questions. "Where is the nearest cafe?" Sentence Structures: Simple: Basic, with a subject and a verb. "The cat sleeps." Compound: Two simple sentences joined. "The sun is shining, and the birds are singing." Complex: Main sentence plus extra details. "I will go to the park when it stops raining." Compound-Complex: Mix of compound and complex. "She likes coffee, but he prefers tea when he wakes up." 37. Derivational typology of words in English Derivation is like playing with words to make new ones. You can add or change parts of a word to create something different. Add to the Front (Prefix): Add "un-" to "happy" to make "unhappy," which means not happy. Add to the End (Suffix): Add "-ness" to "happy" to make "happiness," which means the state of being happy. Change Job (Conversion): "Hand" can be a thing you have or something you do. No need to add anything, just use it differently. Stick Words Together (Compounding): Combine "tooth" and "paste" to get "toothpaste." Make Shorter (Clipping): Take away part of "telephone" and get "phone." Create Shorter Word (Back-formation): From "editorial," you get "editor." Use Initials (Acronymy): "NASA" comes from the first letters of "National Aeronautics and Space Administration." Mix Words (Blending): Blend "breakfast" and "lunch" to get "brunch." Repeat (Reduplication): Say "bye-bye" or "choo-choo" with repeated parts. Move Things Around (Affix Hopping): "Sing" becomes "singer" or "singing" by moving stuff inside. 38. Divergent views on the verbal category of Perfect. The Perfect Tenses and their distribution In English, the perfect tenses are formed using the auxiliary verb "have" combined with the past participle of the main verb. There are three primary perfect tenses: present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect. Present Perfect: Have/has + past participle; Talks about things from the past still important now; "I have finished my homework." Past Perfect: Had + past participle; Shows which of two past actions happened first; "She had already left when I arrived." Future Perfect: Will have + past participle; Tells us about something finished before a future time; "By next year, I will have completed my degree." Divergent Views: Aspect vs. Tense: Some say perfect is more about how an action is happening, not when. Connection with Past: People argue if perfect always talks about the past or also the present. Stative vs. Dynamic Verbs: Some think perfect works better with certain types of verbs. Completion vs. Relevance: People debate if perfect shows an action finished or still matters now. Continuation into the Present: Some wonder if present perfect is about now or just the past. 39-40. Lexical and grammatical aspects of the words. Types of grammatical and lexico-grammatical meaning of the word Words have their main idea (lexical) and a job in sentences (grammatical). Grammatical meaning is about fitting into sentences, while lexicogrammatical mixes word meaning with sentence use. Lexical Aspect: is about words and their main ideas; "Dog" means a four-legged pet. Grammatical Aspect: is about how words work in sentences. In "The dog is barking," "dog" is the subject. Types of Word Meanings: Grammatical Meaning: How a word fits in a sentence or its form in grammar. In "She walks," "walks" shows action now. Lexico-Grammatical Meaning: Mixes word meaning (dictionary) with how it works in a sentence. In "fast runner," "fast" means someone who runs quickly. Grammatical Functions: Words have different jobs in sentences. In "They are singing," "They" is the subject. Lexical Relations: Words connected in meaning, like synonyms or opposites. "Big" and "large" mean the same. Word Forms: Words change shapes in sentences. "Run" turns into "running" in "She is running." 41. Secondary parts of a sentence Object: What or whom the action is happening to; "the ball" in "She kicked the ball." Adjective: A word describing or giving more info about a noun; "happy" in "The happy dog barks." Adverb: A word describing or giving more info about a verb, adjective, or another adverb; "quickly" in "She runs quickly." Preposition: A word showing the relationship between a noun (or pronoun) and other words in the sentence; "on" in "The cat is on the roof." Conjunction: A word connecting words, phrases, or clauses; "and" in "She sings and dances." Interjection: A word expressing strong emotion; "Wow! That's amazing!" 42.Lexical words vs grammatical words. Their semasiological, formal and functional differentiation Lexical Words: are the big, meaningful words that tell us about things, actions, qualities, or ideas. Nouns (like "cat," "book"), verbs (like "run," "eat"), adjectives (like "happy," "blue"), and adverbs (like "quickly," "loudly") are all the important words. Grammatical Words: are the helpers that make sure the sentence works well. They connect and organize the big words but don't have strong meanings on their own. Articles (like "the," "a"), prepositions (like "on," "in"), conjunctions (like "and," "but"), and pronouns (like "he," "it") are the helpful friends. Semasiological Differentiation: Lexical Words: have a clear meaning on their own, talking about real things or actions. Grammatical Words: don't have specific meanings alone; they get their meaning from how they help in a sentence. Formal Differentiation: Lexical Words: are often longer, more diverse, and grab more attention in a sentence. Grammatical Words: are usually shorter, more standard, and work to connect or shape the sentence. Functional Differentiation: Lexical Words: do the heavy lifting, expressing the main ideas, actions, or qualities. Grammatical Words: set up the stage, showing how words relate, connect, and create the structure of a sentence. 43. Grammatical peculiarities of the non-finite forms of the English verb. Non-finite verbs lack tense and do not function as the main verb in a sentence. Instead, they serve various purposes, such as complementing other verbs, adjectives, or nouns. Types of Non-Finite Verb Forms: English features three primary non-finite verb forms: infinitives, gerunds, and participles. 1. Infinitives: Infinitives are the base form of a verb, usually preceded by the word "to." For example, in the sentence "to write is a pleasure," "to write" is the infinitive phrase. Infinitives can function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs within a sentence, showcasing their versatility. 2. Gerunds: Gerunds are verb forms ending in "-ing" that function as nouns. For instance, in the sentence "Swimming is good exercise," "swimming" is a gerund serving as the subject. Gerunds also appear as objects, complements, or within prepositional phrases. 3. Participles: Participles are verb forms often ending in "-ing" (present participle) or "-ed," "-en," or irregular forms (past participle). Participles function as adjectives within a sentence, modifying nouns. For example, in the phrase "the written report," "written" is a past participle serving as an adjective. Functions of Non-Finite Verb Forms: 1. Complementation: Infinitives, gerunds, and participles often complement other verbs. For example, in the sentence "I like to swim," the infinitive "to swim" complements the verb "like." 2. Modification: Participles, particularly present participles, are frequently used to modify nouns, providing additional information about them. In the phrase "the running water," the present participle "running" modifies the noun "water." 3. Subject or Object: Gerunds can function as subjects or objects within a sentence. In "Reading is my favorite hobby," "reading" serves as the subject, while in "I enjoy reading books," "reading books" functions as the direct object. Syntactic Peculiarities: Non-finite verb forms exhibit specific syntactic behaviors that distinguish them from finite verbs. Notably, they lack tense, which means they do not indicate a specific point in time. This absence of temporal information allows for a broader range of applications and interpretations within different contexts. 44. The process of analytization of the English language: analytical tendencies in morphology and syntax Analytization is the general grammatical tendency traceable in the development of some of the Indo-European languages. In English, for instance, the process is extremely intensive and it manifests deep changes in the grammatical structure of the language, in its morphology and in its syntax as well. Analytization as a complex of diachronic processes has been stimulated by some intralingual conditions available within the Old English language. An insight into the peculiarities of the Old English grammatical structure makes us aware of the fact that the process started in syntax first. Analytical Tendencies in Morphology: Analytical tendencies in the Morphology of English are vividly revealed in the spheres of Form-derivation and Word-building. It is the form-derivation and the word-building of the Verb which have undergone changes. Since the Early Middle English period the paradigm of the verb has become highly developed and analytical in nature because most of the paradigmatic forms of the verb are derived as analytical formations: e.g. Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous and other verb-forms. As to the analytical tendencies in the word-building of the verb, they are manifested by the productivity of those word-building devices which are considered to be characteristic of analytical languages: conversion, postposition formation and phrasing. All these devices are rather productive for the derivation of English verbs. Alongside the analytization of the verb-paradigm and its word-building other analytical tendencies can be traced in the morphology of English. Firstly, the unification of grammatical forms has taken place in the paradigmatic derivation of the main word-forms. Secondly, the process of analytization led to the new forms of the word-class determination: the determination of the class-membership by means of special function-words (determiners) has become regular. Loss of Inflections: One prominent feature of the analytization process in English is the reduction of inflections. Old English, the language's predecessor, relied heavily on inflections to convey grammatical information. However, Modern English has experienced a gradual loss of inflections, with a shift towards using auxiliary verbs and word order to convey meaning. Example: Old English: "Sēo sunne scīnð" (The sun shines) Modern English: "The sun shines" Use of Auxiliary Verbs: Analytical tendencies manifest in the increased reliance on auxiliary verbs to express grammatical nuances such as tense, aspect, and modality. Example: Old English: "Ic wille lufian" (I will love) Modern English: "I will love" Analytical Tendencies in Syntax: Analytical tendencies involve changed the forms of syntactic connection: agreement and case-government gave way to adjoinment and enclosure which are marked not by case-inflections but by the word-order. By agreement we mean a method of expressing a syntactical relationship, which consists in making the subordinate word take a form similar to that of the word to which it is subordinate. In Modern English this can refer only to the category of number: a subordinate word agrees in number with its head word if it has different number forms at all. This is practically found in two words only, the pronouns this and that, which agree in number with their head word. This tree/that tree/these trees/those trees Since no other word, to whatever part of speech it may belong, agrees in number with its head word, these two pronouns stand quite apart in the Modern English syntactical system. By government we understand the use of a certain form of the subordinate word required by its head word, but not coinciding with the form of the head word itself. The only thing that may be termed government in Modern English is the use of the objective case of personal pronouns and of the pronoun who when they are subordinate to a verb or follow a preposition. Thus, for instance, the forms me, him, her, us, them, are required if the pronoun follows a verb (e. g. find or invite) or any preposition whatever. Who(m) did you see? Word Order Changes: The analytization process is evident in shifts in word order to convey grammatical relationships. English tends to rely on a fixed word order, especially in declarative sentences, using auxiliary verbs to indicate tense and other grammatical features. Example: Old English: "Hēo hine sēoþ" (She sees him) Modern English: "She sees him" Phrasal Constructions: English employs phrasal constructions, combining words to convey complex meanings, instead of relying solely on morphological changes. Example: Old English: "Wesan tō hūse" (To be at home) Modern English: "To be at home" Expansion of Compound Words: The analytization process is also reflected in the expansion of compound words, wherein separate words are used to express concepts that might have been conveyed through a single, inflected word in earlier stages of the language. Example: Old English: "Sēocehǣleþ" (Sickness) Modern English: "Sick health" or "Health sickness" 45. Composite sentence: compound and complex sentences. Composite sentences, a key component of syntactic structure, encompass both compound and complex sentences. I. Compound Sentences: A compound sentence is formed by combining two or more independent clauses. Independent clauses are complete sentences that can stand alone, each expressing a complete thought. The conjunctions "and," "but," "or," "nor," "for," "yet," and "so" are commonly used to join independent clauses in a compound sentence. Additionally, a semicolon can be used to connect closely related independent clauses. Examples: 1. She loves reading, and he enjoys playing sports. 2. The sun was setting, but the sky was still ablaze with color. 3. You can stay at home, or you can join us for the party. Compound sentences allow for the expression of related ideas, contrasting information, or presenting alternatives. They enhance the flow of a narrative by creating a dynamic relationship between independent clauses. II. Complex Sentences: A complex sentence consists of an independent clause and one or more dependent clauses. A dependent clause, also known as a subordinate clause, cannot stand alone as a complete sentence and relies on the independent clause for context and meaning. Subordinating conjunctions such as "although," "because," "since," "while," and "if" are frequently used to introduce dependent clauses in complex sentences. Relative pronouns like "who," "whom," "whose," "which," and "that" can also serve this purpose. Examples: 1. Although it was raining, they decided to go for a walk. 2. She studied hard because she wanted to ace the exam. 3. The book that you lent me is fascinating. Complex sentences enable the expression of complex relationships between ideas, showing cause and effect, contrast, or providing additional information. The dependent clause enhances the meaning of the independent clause, offering a nuanced and layered communication. Conclusion: Compound sentences allow for the combination of independent clauses, facilitating the expression of related or contrasting ideas. On the other hand, complex sentences add depth to communication by incorporating dependent clauses that provide additional context, cause-and-effect relationships, or contrasting elements. +A simple sentence consists of just one independent clause—a group of words that contains at least one subject and at least one verb and can stand alone as a complete sentence—with no dependent clauses. My partner loves to hike. Veterinary technicians work alongside veterinarians. Although these examples include direct objects and prepositional phrases, they are simple in structure because they each have just one independent clause. 46. Word-classes in accordance with their referentiality and nominativity (notional, semi-notional and non-notional). 1. Notional Words: Notional words are those with a clear and concrete meaning, representing entities, actions, or qualities. They convey specific content and contribute directly to the overall meaning of a sentence. The primary notional word classes include nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. The features of the noun within the identificational triad "meaning - form - function" are, correspondingly, the following: 1) the categorial meaning of substance ("thingness"); 2) the changeable forms of number and case; the specific suffixal forms of derivation (prefixes in English do not discriminate parts of speech as such); 3) the substantive functions in the sentence (subject, object, substantival predicative); prepositional connections; modification by an adjective. The features of the adjective: 1) the categorial meaning of property (qualitative and relative); 2) the forms of the degrees of comparison (for qualitative adjectives); the specific suffixal forms of derivation; 3) adjectival functions in the sentence (attribute to a noun, adjectival predicative). The features of the numeral: 1) the categorial meaning of number (cardinal and ordinal); 2) the narrow set of simple numerals; the specific forms of composition for compound numerals; the specific suffixal forms of derivation for ordinal numerals; 3) the functions of numerical attribute and numerical substantive. The features of the pronoun: 1) the categorial meaning of indication (deixis); 2) the narrow sets of various status with the corresponding formal properties of categorial changeability and word-building; 3) the substantival and adjectival functions for different sets. The features of the verb: 1) the categorial meaning of process (presented in the two upper series of forms, respectively, as finite process and non-finite process); 2) the forms of the verbal categories of person, number, tense, aspect, voice, mood; the opposition of the finite and non-finite forms; 3) the function of the finite predicate for the finite verb; the mixed verbal - other than verbal functions for the non-finite verb. The features of the adverb: 1) the categorial meaning of the secondary property, i.e. the property of process or another property; 2) the forms of the degrees of comparison for qualitative adverbs; the specific suffixal forms of derivation; 3) the functions of various adverbial modifiers. We have surveyed the identifying properties of the notional parts of speech that unite the words of complete nominative meaning characterised by selfdependent functions in the sentence. Examples: - Nouns: "Dog," "mountain," "happiness" - Verbs: "Run," "sing," "think" - Adjectives: "Blue," "happy," "tall" - Adverbs: "Quickly," "joyfully," "soon" In sentences like "The cat sleeps peacefully," "cat" (noun) and "sleeps" (verb) are notional words contributing directly to the meaning. 2. Semi-Notional Words: Semi-notional words have a mix of concrete meaning and grammatical function. While they carry some semantic content, their primary role is to fulfill grammatical or structural functions in a sentence. Pronouns and certain adverbs fall into the semi-notional category. Examples: - Pronouns: "He," "she," "it" - Adverbs: "Here," "there," "now" In the sentence "She sings beautifully," "she" (pronoun) and "beautifully" (adverb) are semi-notional, as they contribute to both grammatical structure and meaning. 3. Non-Notional Words: Non-notional words lack specific meaning and do not contribute directly to the content of a sentence. Contrasted against the notional parts of speech are words of incomplete nominative meaning and non-self-dependent, mediatory functions in the sentence. These are functional parts of speech. They serve primarily grammatical functions, aiding in sentence structure or facilitating connections between notional words. Articles, conjunctions, prepositions, and auxiliary verbs are common examples of non-notional words. The article expresses the specific limitation of the substantive functions. The preposition expresses the dependencies and interdependences of substantive referents. The conjunction expresses connections of phenomena. The particle unites the functional words of specifying and limiting meaning. To this series, alongside of other specifying words, should be referred verbal postpositions as functional modifiers of verbs, etc. The modal word, occupying in the sentence a more pronounced or less pronounced detached position, expresses the attitude of the speaker to the reflected situation and its parts. Here belong the functional words of probability (Probably, perhaps, etc.), of qualitative evaluation (Fortunately, unfortunately, luckily, etc.), and also of affirmation and negation. The interjection, occupying a detached position in the sentence, is a signal of emotions. (wow, oh). Examples: - Articles: "A," "an," "the" - Conjunctions: "And," "but," "or" - Prepositions: "On," "under," "between" - Auxiliary verbs: "Is," "have," "will" In the sentence "The sun is shining," "the" (article) and "is" (auxiliary verb) are non-notional, providing grammatical structure without conveying specific content. 47. Word order. Word order serves as the structural backbone of English syntax, determining the arrangement of words in a sentence to convey meaning and establish grammatical relationships. 1.Basic Word Order (SVO – subject-verb-object): English adheres primarily to the SVO word order, wherein a sentence typically begins with the subject, followed by the verb, and concludes with the object. This foundational structure forms the basis for clear and coherent communication. Examples: "The cat (subject) chased (verb) the mouse (object)." "She (subject) is reading (verb) a fascinating book (object)." 2.Inversion: Inversion occurs when the typical SVO word order is altered for emphasis, questions, or stylistic reasons. This often involves placing the auxiliary verb or modal verb before the subject. Examples: "Rarely have I (subject) seen (verb) such a spectacular sight (object)." "Can you (subject) help (verb) me (object) with this?" 3.Subject-Verb Agreement: Subject-verb agreement is vital in English, ensuring that the verb corresponds in number with the subject. Examples: "The dog (singular subject) barks (singular verb)." "The dogs (plural subject) bark (plural verb)." 4.Adjective-Noun Order: Adjectives in English typically precede the noun they modify. The order is generally opinion, size, age, shape, color, proper adjective, and then the noun. Examples: "A beautiful (opinion) old (age) wooden (material) door (noun)." "She bought a new (age) red (color) car (noun)." 5.Adverb Placement: Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs in a sentence. They often appear after the main verb but before the object. Examples: "He speaks (verb) English (adverb) fluently." "She danced (verb) gracefully (adverb) at the party." 6.Time-Manner-Place Adverbial Order: Adverbials expressing time, manner, and place typically follow a specific order in English sentences: time, manner, and place. Examples: "She (subject) arrived (verb) at the airport (place) early (time) in the morning (place)." "He (subject) played (verb) the piano (object) beautifully (manner) in the concert hall (place)." 7.Indirect Object-Direct Object Order: When both an indirect object and a direct object are present, the indirect object usually precedes the direct object. Examples: "She (subject) gave (verb) her friend (indirect object) a gift (direct object)." "He (subject) sent (verb) his sister (indirect object) a postcard (direct object)." 48. Word-classification into "parts of speech" in English. 1. Proceeding in the usual order, we start with the noun, or substantive. (1) Meaning: thingness. beauty, peace, necessity, journey, and everything else presented as a thing, or object. (2) Form. Nouns have the category of number (singular and plural), though some individual nouns may lack either a singular or a plural form. They also, in the accepted view, have the category of case (common and genitive); (3) Function., (a) Combining with words to form phrases. A noun combines with a preceding adjective (large room), or occasionally with a following adjective (times immemorial), with a preceding noun in either the common case (iron bar) or the genitive case (father's room), with a verb following it (children play) or preceding it (play games). Occasionally a noun may combine with a following or a preceding adverb (the man there; the then president). It also combines with prepositions (in a house; house of rest). It is typical of a noun to be preceded by the definite or indefinite article (the room, a room), (b) Function in the sentence. A noun may be the subject or the predicative of a sentence, or an object, an attribute, and an adverbial modifier. It can also make part of each of these when preceded by a preposition. 2. the adjective. 1.Meaning. The adjective expresses property 2.Form. Some adjectives form degrees of comparison (long. longer, longest). (3) Function, (a) Adjectives combine with nouns both preceding and (occasionally) following them (large room, times immemorial). They also combine with a preceding adverb (very large). Adjectives can be followed by the phrase "preposition + noun" (free from danger). Occasionally they combine with a verb (married young), (b) In the sentence, an adjective can be either an attribute (large room) or a predicative (is large). It can also be an objective predicative (painted the door green). The pronoun. (1) Some pronouns share essential peculiarities of nouns, (e.g. he), while others have much in common with adjectives (e. g. which). This made some scholars think that pronouns were not a separate part of speech at all and should be distributed between nouns and adjectives. The meaning of pronouns as a part of speech can be stated as follows: pronouns point to the things and properties without naming them. Thus, for example, the pronoun it points to a thing without being the name of any particular class of things. The pronoun its points to the property of a thing by referring it to another thing. The pronoun what can point both to a thing and a property. 2.Form. Some of them have the category of number (singular and plural), e. g. this, while others have none such category, e. g. somebody. Again, some pronouns have the category of case (he — him, somebody — somebody's),' while others have none (something). 3.Function, (a) Some pronouns combine with verbs (he speaks, find him), while others can also combine with a following noun (this room), (b) In the sentence, some pronouns may be the subject (he, what) or the object, while others are the attribute (my). Pronouns can be predicatives. Personal Pronoun: He is my friend; I saw him yesterday. Demonstrative Pronoun: I prefer this book over that one. 4.Numerals. The so-called cardinal numerals (one, two) are somewhat different from the so-called ordinal numerals (first, second). Meaning. Numerals denote either number or place in a series. Form. Numerals are invariable. Function, As far as phrases go, both cardinal and ordinal numerals combine with a following noun (three rooms, third room.); occasionally a numeral follows a noun. (soldiers three, George the Third). 5.Verb: Verbs express actions, states, or occurrences. They are central to constructing sentences and can be categorized into action verbs, linking verbs, and auxiliary verbs. Function: Verbs serve as the main predicate in a sentence, indicating what the subject does or experiences. Form: Verbs can be finite (e.g., walks, talks) or non-finite (e.g., to walk, walking), and they change form to indicate tense, aspect, and mood. Examples: Action Verb: She runs every morning. Linking Verb: The soup tastes delicious. Auxiliary Verb: I have completed the assignment. 6.Adverb: Meaning: Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs, indicating manner, place, time, or degree. Function: Adverbs provide additional information about how, when, where, or to what extent an action occurs. Form: Adverbs can be single words (e.g., quickly) or phrases (e.g., very slowly). Example: She spoke softly during the meeting. 7.Preposition: Meaning: Prepositions show relationships between nouns (or pronouns) and other words in a sentence. Function: Prepositions indicate location, time, or direction. Form: Prepositions include words like in, on, under, between, etc. Example: The book is on the shelf. 8.Conjunction Meaning: Conjunctions connect words, phrases, or clauses. Function: Conjunctions establish relationships between elements in a sentence. Form: Conjunctions can be coordinating (e.g., and, but) or subordinating (e.g., because, although). Example: He likes both tea and coffee. 9.Interjection: Meaning: Interjections express strong emotions or reactions. Function: Interjections stand alone and are often followed by an exclamation mark. Form: Interjections include expressions like wow, oh, alas. Example: Wow! that's amazing! 49. Different kinds of Passive Voice constructions. Direct and Indirect Passive. Types of Passive Constructions depend upon the type of the object of the active sentence. The Direct Passive The direct object is used after transitive verbs without any preposition. It denotes a person or thing directly affected by the action of the verb. I helped my brother in his work. There are a few English verbs which can have two direct objects. I asked him his name. Forgive me this question. She taught them French. The DP is a part of 2 widely used constructions: a) it forms the basis of the complex subject He was seen talking to the Minister. b) constructions with a formal ‘it’ as subject may also contain the passive of verbs denoting mental and physical perceptions, suggestions, order, request, decision, as well as verbs of saying. Such constructions are followed by a clause introduced by a conjunction that: It was known that she would not tolerate any criticism. Restrictions to the application of the DP. a) due to the nature of the DP. The passive construction is impossible, when the direct object is expressed by: 1) an infinitive We arranged to meet at five o’clock. 2) a clause I saw that he knew about it. 3) a reflexive pronoun or a noun with a possessive pronoun referring to the same person as the subject of the sentence He hurt himself. He cut his finger. b) the verb and the direct object are so closely connected, that they form a set phrase and cannot be separated (to keep one’s word, to lose one’s patience, to take alarm etc). However, some phrases of this kind admit a passive construction (to take care, to take no notice, to pay attention, to take responsibility). In his school a great deal of attention is paid to maths. c) in addition to intransitive verbs, some transitive verbs are not used in the passive, at least in certain uses: The boy resembles his father. The hat suits (becomes) you. The coat does not fit you. He has (possesses) a sense of humour. He lacks confidence. The place holds 500 people. The Indirect Passive If the indirect object becomes the subject of the passive construction, we speak about the indirect passive. The Indirect object denotes a living being to whom the action of the verb is directed. It usually expresses the addressee of the action expressed by a transitive verb or sometimes intransitive verb. She gave him a book to read. There is a number of verbs in English which take two objects – direct and indirect. The most frequently used are to give, to grant, to leave, to lend, to offer, to pay, to promise, to send, to show, to tell. These verbs may have two passive constructions. a) the DP When I came to the office a telegram was given to me. b) the indirect passive When I came to the office I was given a telegram. The IndP is found with set phrases containing the verbs to give/to grant followed by a noun. I was given a chance to explain. He’d been granted leave of absence from his work. Key Differences: Agent Presence: Direct Passive: The agent (doer of the action) may be explicitly mentioned with the preposition "by." Indirect Passive: The agent is either expressed using a reflexive pronoun or omitted. Emphasis: Direct Passive: Places explicit emphasis on the doer or agent. Indirect Passive: Focuses on the action and the recipient without highlighting the doer. + The Prepositional Passive Verbs which require a prepositional object in the active, can be also used in the passive. In this case the subject of the passive construction corresponds to the prepositional object. The preposition retains its place after the verb. This construction may be called the Prepositional Passive. The doctor was sent for. He was highly thought of. The direct object after some of these verbs is rather often expressed by a clause. In this case the only possible passive construction is the one with a formal it as subject. It had been explained to Sylvia that Renny had gone. There is another passive construction possible in English: the subject of the passive construction corresponds to an adverbial modifier of place in the active construction. In this case the preposition also retains its place after the verb. The bed had been slept in. These chairs have once been sat in by cardinals. In standard passive constructions the subject is the recipient of some action (e.g. I’ve been sacked). In causative constructions the object is the recipient of an action – the subject is in some way responsible for what happened, but didn’t do it. We form the causative with: to have/to get + noun or pronoun object + past participle We had the rubbish taken away. I’ve got two of my stories published. We also use get in place of have in the causative to say that something is urgent Have the car repaired! Get the car repaired! (more urgent) 50. Lexico-grammatical classes of words in English: parts of speech and form-classes. 1. Parts of Speech: Parts of speech categorize words based on their grammatical functions in a sentence. The primary parts of speech in English include: Noun: A word that represents a person, place, thing, or idea. Example: cat, city, love. Pronoun: A word used to replace a noun to avoid repetition. Example: he, she, it. Verb: A word that expresses an action or a state of being. Example: run, swim, is. Adjective: A word that describes or modifies a noun or pronoun. Example: beautiful, tall, happy. Adverb: A word that modifies a verb, adjective, or another adverb, often indicating how, when, where, or to what degree. Example: quickly, very, there. Preposition: A word that shows the relationship between a noun (or pronoun) and another word in the sentence. Example: in, on, under. Conjunction: A word that connects words, phrases, or clauses. Example: and, but, or. Interjection: A word or phrase used to express strong emotion. Example: Wow! Ouch! 2. Form-Classes: Form-classes categorize words based on their morphological and syntactic features. These classes include: Content Words: Words that carry meaning and contribute to the overall message of a sentence. This category includes nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Function Words: Words that serve grammatical functions and contribute to the structure of a sentence without conveying specific meaning. This category includes pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, and articles (a, an, the). Open-Class Words: Words that allow for the addition of new words over time. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs are open-class words. Closed-Class Words: Words that have a relatively fixed membership and do not readily admit new members. Pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, and articles are closed-class words. 51. Types of word-forms derivation (Sound alteration) Word-form derivation through sound alteration involves changes in the phonetic or sound structure of words to create new forms. Here are some types of sound alterations commonly observed in linguistic processes: Consonant Gradation: This involves changes in the consonant sounds within a word, often influenced by grammatical or morphological factors. Example: English "sing" (base form) vs. "sang" (past tense). Vowel Gradation (Ablaut): Involves changes in vowel sounds within a word, often occurring in relation to tense, aspect, or grammatical features. Example: English "sing" (base form) vs. "sang" (past tense). Reduplication: Repetition of a portion of a word, which can involve full or partial repetition of sounds. Example: Tagalog "takbo" (to run) vs. "tatakbo" (will run). Initial Sound Alternation (Initial Mutation): Changes in the initial consonant sound of a word, often due to morphological or syntactic factors. Example: Irish "bean" (woman) vs. "bhean" (of a woman). Final Sound Alternation (Final Mutation): Changes in the final consonant sound of a word based on grammatical or morphological factors. Example: Hebrew "katav" (he wrote) vs. "ktiva" (writing). Assimilation: The process by which a sound becomes more similar to a neighboring sound. Example: English "im-" (prefix) assimilates to "il-" before words starting with "l," as in "impossible" vs. "illegal." Dissimilation: The process by which two nearby similar sounds become less alike. Example: Latin "humerus" (shoulder) vs. Old English "sweora" (shoulder). Epenthesis: The addition of one or more phonemes to a word. Example: Spanish "inflamable" (flammable) with the addition of the extra syllable "in-" for clarity. Deletion (Apheresis, Syncope, Apocope): A type of sound alteration involving the removal of one or more sounds from a word. Example: English "gonna" (going to) involves the deletion of the middle sound "i." 52. Synthetical and analytical ways of word-class determination. Synthetical Approach: 1.Inflectional Morphology: In synthetical analysis, the focus is on inflectional morphemes that are added to a base word to indicate grammatical features such as tense, number, gender, case, etc. Example: In English, adding "-s" to "cat" indicates plurality ("cats"). 2.Word Endings: The ending of a word often provides clues about its grammatical category. Example: English nouns often end in -"tion" ("celebration"), adjectives in -"able" ("comfortable"), and verbs in -"ing" ("running"). 3.Word Internal Changes: Synthetical analysis also considers internal changes within a word, such as vowel or consonant alternations, to determine its grammatical function. Example: English "go" (verb) vs. "went" (past tense). Analytical Approach: 1.Positional Distribution: Analytical analysis focuses on the position of a word within a sentence and its syntactic role to determine its part of speech. Example: In English, words occurring before a noun may be adjectives, and those before a verb may be adverbs. 2.Semantic Criteria: Analytical analysis takes into account the meaning of a word and its relationship to other words in a sentence. Example: In the sentence "The cat is sleeping," the word "sleeping" is a verb because it describes an action. 3.Function in Context: The function of a word in a specific context can be indicative of its part of speech. Example: In the sentence "I saw the car," "saw" is a verb, while in "I have a saw," "saw" is a noun. 4.Syntactic Structure: Analytical analysis considers the syntactic structure of a sentence to determine the role of a word. Example: In English, words following "to" are often verbs (e.g., "to run") 53. Suppletivity (Types of word-form derivation). Suppletivity is a linguistic phenomenon in which an irregular form is used in a paradigm where one might expect a regular form based on the typical patterns of inflection or derivation. In other words, instead of a regular morphological alteration, a completely different form is used for a specific grammatical feature. Suppletive forms often do not share a common root and are not predictable based on regular linguistic rules. Here are a few examples: Verb Tenses: The English verb "to be" exhibits suppletive forms in its various tenses: Present: I am Past: I was Future: I will be Comparative and Superlative Adjectives: Some adjectives in English have suppletive forms for their comparative and superlative degrees: Good (positive), Better (comparative), Best (superlative) Bad (positive), Worse (comparative), Worst (superlative) Pronouns: In English, the pronoun "I" has a suppletive form in the accusative case: Nominative: I Accusative: Me Nouns: In some languages, the plurals of certain nouns are formed with suppletive forms: English: Man (singular), Men (plural) German: Mann (singular), Männer (plural) 54. Determiners and their functional significance. Morphological vs syntactical determiners. Morphological Determiners: 1.Definite Article (the): Indicates a specific or previously mentioned noun. Example: "The cat is on the roof." 2.Indefinite Articles (a, an): Introduce non-specific or generic nouns. Example: "A dog barked outside." 3.Demonstratives (this, that, these, those): Specify the proximity or distance of the noun in relation to the speaker. Example: "This book is interesting." 4.Possessives (my, your, his, her, its, our, their): Indicate ownership or possession. Example: "My car is parked over there." 5.Quantifiers (some, any, many, few, several, all, much, more, most, etc.): Provide information about the quantity or amount of the noun. Example: "I have some friends coming over." Syntactical Determiners: 1.Numeral Determiners (one, two, three, first, second, third, etc.): Indicate the number or order of items. Example: "I have two apples." 2.Distributive Determiners (each, every, either, neither): Refer to individual members of a group. Example: "Each student should submit their assignment." 3.Interrogative Determiners (which, what, whose): Used in questions to inquire about the identity, choice, or possession. Example: "Which book do you want?" 4.Relative Determiners (whose, which, that): Introduce relative clauses and specify the noun they modify. Example: "The girl whose brother is a doctor is my friend." 5.Exclamatory Determiners (what, such): Express strong emotions or surprise. Example: "What a beautiful day!" Functional Significance of Determiners: 1.Identification and Specification: Determiners help identify and specify nouns, making the meaning of a sentence clearer. 2.Definiteness and Indefiniteness: Definite and indefinite articles indicate whether a noun refers to a specific or non-specific entity. 3.Possession: Possessive determiners convey ownership or association with someone or something. 4.Quantification: Quantifiers provide information about the quantity or amount of the noun. 5.Contextual Clarification: Determiners contribute to the context and overall coherence of a sentence by conveying important information about the nouns they modify. 55. The noun. Its lexico-grammatical characteristics, The category of number, The meaning of the Singular and the Plural A noun is a part of speech that represents a person, place, thing, idea, or concept. It serves as the subject or object of a verb, or it functions as the object of a preposition. Nouns have several lexico-grammatical characteristics: 1.Gender: Some languages assign gender to nouns (e.g., masculine, feminine, neuter), impacting agreement with other elements in a sentence. 2.Number: Nouns can be singular or plural, indicating whether there is one or more than one of the referent. 3.Case (in languages with case markings): Certain languages inflect nouns based on their grammatical role in a sentence (e.g., nominative, accusative, genitive). 4.Countability: Nouns can be countable (e.g., "book," "cat") or uncountable (e.g., "water," "information"). 5.Articles: Articles (definite "the" or indefinite "a/an") often accompany nouns to provide information about definiteness. 6.Possession: Nouns can be marked for possession through possessive forms (e.g., "John's book"). Category of Number: The category of number refers to the grammatical distinction between singular and plural forms of nouns. Singular: Refers to one individual or item. Example: "book," "cat," "house." Plural: Refers to more than one individual or item. Example: "books," "cats," "houses." Meaning of the Singular and the Plural: Singular: The singular form of a noun is used when referring to a single entity or item. Example: "The cat is sleeping." (referring to one cat) "I bought a book." (referring to one book) Plural: The plural form of a noun is used when referring to more than one entity or item. Example: "The cats are playing." (referring to multiple cats) "We have three apples." (referring to multiple apples) 56. Grammatical peculiarities of Passive constructions in English, Prepositional Passive Passive constructions in English involve a change in the typical word order of a sentence. In a passive construction, the subject of the sentence undergoes the action rather than performing it. Two common types of passive constructions in English are the regular passive voice and prepositional passive. Grammatical Peculiarities of Passive Constructions in English: 1.Regular Passive Voice: -Formation: The passive voice is typically formed using a form of the verb "to be" (e.g., is, am, are, was, were) followed by the past participle of the main verb. Example: "The book was read by the student." -Agent (Optional): The doer of the action (the agent) is optional and can be included using the preposition "by," but it can also be omitted. Example: "The book was read by the student." (with agent) or "The book was read." (without agent) -Focus on the Action or Receiver: Passive constructions are often used to emphasize the action or the recipient of the action rather than the doer. Example: "The cake was baked by Mary." (focus on Mary's action) vs. "Mary baked the cake." (focus on Mary) -Tense Consistency: The tense of the auxiliary verb "to be" indicates the tense of the passive construction. Example: "The letter is being written by the secretary." (present continuous passive) 2.Prepositional Passive: -Formation: In prepositional passive constructions, the preposition "by" is used to introduce the agent of the action. Example: "The house was built by the construction workers." -Agent Introduced by "By": The agent is explicitly mentioned and introduced by the preposition "by." Example: "The painting was created by the artist." -Focus on the Agent: Prepositional passive constructions often emphasize the agent or doer of the action. Example: "The play was written by Shakespeare." (focus on Shakespeare's action) -Common with Verbs That Don't Take Direct Objects: Prepositional passive constructions are frequently used with intransitive verbs or verbs that do not typically take direct objects. Example: "The children were frightened by the thunder." -Flexibility in Agent Placement: In prepositional passives, the agent can be placed at different positions in the sentence for stylistic reasons. Example: "By the construction workers, the house was built." 57.General characterization of the main lexico-grammatical word-classes in English. NOUN Meaning: Nouns are words that represent people, places, things, or ideas. Form:Nouns have the category of number (singular and plural), have the category of case (common and genitive) Function: Combining with Words to Form Phrases: Nouns combine with various elements such as adjectives (large room), preceding or following nouns (iron bar, father's room), verbs (children play, play games), adverbs (the man there, the then president), and prepositions (in a house, house of rest). Nouns are typically preceded by definite or indefinite articles (the room, a room). Function in the Sentence: Nouns serve multiple functions in a sentence, including being the subject(Children play in the park every afternoon.), predicative(The goal of the game is victory.), object(She admired the painting in the gallery.), attribute(The sunset view from the mountain was breathtaking.), or adverbial modifier(He walked to the store yesterday.). ADJECTIVE Meaning: Adjectives describe or modify nouns, providing additional information about their qualities. Form: Adjectives can vary in degrees of comparison—positive(happy), comparative(happier), and superlative(happiest). Function: Combination with Nouns: Adjectives can precede or occasionally follow nouns (e.g., "large room," "times immemorial"). They can combine with a preceding adverb (e.g., "very large") or a preceding verb (e.g., "married young"). Adjectives can be followed by the phrase "preposition + noun" (e.g., "free from danger"). Functions in a Sentence: In a sentence, adjectives can serve as attributes (e.g., "large room"), as predicatives (e.g., "is large"), as objective predicatives (e.g., "painted the door green"). VERB Meaning: Verbs express actions, process, or states of being. Form:Verbs can have different forms indicating tense, aspect, mood, voice, person, and number. They include base forms, past tense, past participle, and present participle. Function: Verbs are connected with a preceding noun (children play) with a following noun (play games) with adverbs (write quickly) with an adjective (married young). In a sentence a verb (in its finite forms) is always the predicate or part of it (link verb). The functions of the verbals (infinitive, participle, and gerund) are considered separately. PRONOUN Meaning: The meaning of the pronoun is difficult to define. A pronoun is a word used to replace a noun(boy - he) or adjective(which). Form: Some of pronouns have the category of number (singular and plural) (f.e: this-these).Some pronouns have the category of case (he — him, somebody — somebody's), while others have none (something). Types of pronoun: Possessive = mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs Reflexive = myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, oneself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves Reciprocal = each other, one another Relative = that, which, who, whose, whom, where, when Demonstrative = this, that, these, those Interrogative = who, what, why, where, when, whatever? Indefinite = anything, anybody, anyone, something, somebody, someone, nothing, nobody, none, no one Function: Some pronouns combine with verbs (he speaks, find him), while others can also combine with a following noun (this room). In the sentence, some pronouns may be the subject (he has a car), the object(I gave the gift to him.), the attribute (The book on the shelf is mine.), the predicative (The winner of the contest is her.) ADVERB Meaning: The meaning of the adverb as a part of speech is hard to define, but we can indentify it as “property of an action or of a property”. Some adverbs indicate time or place of an action (yesterday, here), while others indicate its property (quickly) and others again the degree of a property (very). Form: Adverbs are invariable. Some of them, however, have degrees of comparison (fast, faster, fastest). Function: An adverb combines with a verb (run quickly), with an adjective (very long), with a noun (the then president) with a phrase (so out of things). An adverb can sometimes follow a preposition (from there). In a sentence an adverb is almost always an adverbial modifier, or part of it (from there), but it may occasionally be an attribute. NUMERALS Meaning: Numerals represent numbers and can be cardinal (e.g., one, two) or ordinal (e.g., first, second). Form: Numerals are invariable. (незмінні) Function: both cardinal and ordinal numerals combine with a following noun (three rooms, third room); occasionally a numeral follows a noun (George the Third). In a sentence, a numeral most usually is an attribute (She bought a dress with three pockets.); a subject (Five students participated in the play.) a predicative (The answer is twelve.) an object (Please bring two chairs to the meeting room.) CONJUNCTIONS Meaning: Conjunctions are words that connect words, phrases, or clauses within a sentence. Form: Conjunctions can be categorized into two main types: Coordinating Conjunctions: These connect elements of equal grammatical rank, such as words, phrases, or independent clauses. Examples include "for, And, Nor, but, or, yet, so" (She enjoys reading and painting in her free time.) Subordinating Conjunctions: These introduce dependent clauses and establish relationships between the dependent clause and the rest of the sentence. Examples include "after, Although, as soon as, Because, before" (They canceled the picnic because of the rain.) Correlative conjunctions work in pairs (example: either/or, both/and, not only/but also, as/as). Function: Coordinates words, phrases, or clauses of equal grammatical rank (She likes both tea and coffee.) Introduces subordinate clauses, creating complex sentences (He ate dinner before watching a movie.) Adds elements together (He is smart and hardworking.) Highlights differences or contrast (She is tall, but he is short.) Indicates reasons (They left early because it was getting late.) Presents options or alternatives (You can choose either tea or coffee.) Expresses results (It was raining, so they stayed at home.) Introduces conditional clauses (We'll go for a walk if the weather is nice.) PREPOSITIONS Meaning: Prepositions are obviously that of relations between things. Form: Prepositions are invariable. Function: Prepositions enter into phrases in which they are preceded by a noun, adjective, numeral, stative, verb or adverb, and followed by a noun, adjective, numeral or pronoun. In a sentence a preposition never is a separate part of it. It goes together with the following word to form an object, adverbial modifier, predicative or attribute, and in extremely rare cases a subject (There were about a hundred people in the hall). 58. Synthetical and analytical ways of word-class determination. The modern classification of parts of speech has ancient origins. Two key principles, though criticized, have been proposed: 1. Semantic Approach: It is criticized for limitations. Nouns (things), verbs (actions or states), adjectives (qualities) are classified based on meaning. However, words like 'action' challenge this principle, making it unreliable. 2. Formal Approach: Classifies words based on form. Declinable (inflected) includes noun-words , adjective-words, and verbs. Indeclinable (uninflected) includes adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections. Functionality and Classification: Parts of speech fall into two groups: Notional (Noun, verb, adj, adv) and Structural (Functional). Notional parts (e.g., Noun, verb, adjective) constitute 93% of English vocabulary, possessing independent meaning. They include numerals and pronouns. Notional words have distinct lexical meaning and perform various syntactic functions. For example, word “cat” is a noun which means a small pet known for cathcing mice and the word can be plural “cats”. Structural (Functional) Parts of Speech: Syntagmatic connections between main parts. Prepositions (act within a clause) and conjunctions (unite words, clauses, or separate sentences). Express relations but don't denote objects or notions. Functional words have less distinct meaning, don't perform syntactic functions, but express relations. For example, in a sentence “I go to school and study there” the word “and” is a conjunction which connects two equal sentences. Ninth Part of Speech: Interjections: Express emotions, unpredictable in form, some similar to word combinations (e.g., My God!). Often phonetic sounds of surprise or pause-fillers. (e.g., Wow, Umm…) Play an emotional role (e.g., Oh no!) There are some debatable questions about: 1. Words of category of state (e.g., "awake"). Semantically they express state, but some grammatitians argue that they should be grouped separately. Adjectives always express statel; 2. Modal words (e.g., "certainly, possibly") debated for a separate part of speech. In fact, they appear to be functionally and structurally close to adverbs; 3. Particles (e.g., "only, merely") considered a subclass of limiting adverbs. 4. Articles ( which are similar to nouns). 59. Semantical and structural typology of adjectives. According to their meaning and grammatical characteristics adjectives have two types: qualitative adjectives and relative adjectives. 1. Qualitative adjectives denote qualities of a substance directly as size, shape, colour, physical and mental qualities, qualities of general estimation: For example: little, large, high, soft, hard, warm, white, blue, pink, strong, hold, beautiful, important, necessary, etc. Characteristics of qualitative adjectives: Most qualitative adjectives have degrees of comparison(comparative and superlative): big, bigger, the biggest. They have certain typical suffixes, such as -ful, -less, -ous, -ent, -able, -y, -ish: careful, careless, dangerous, convenient, comfortable, silvery. From most of them adverbs can be formed by the suffix -ly: graceful — gracefully. Most qualitative adjectives can be used as attributes and predicatives: The young girl is smiling. 2.Relative adjectives denote qualities of a substance through their relation to materials (wooden), to place (Italian, Asian), to time (monthly, weekly), to some action (preparatory=підготовчий) Characteristics of relative adjectives: Relative adjectives have no degrees of comparison. They have certain typical suffixes, such as -en, -an, -ist, -ic, -ical: wooden, Italian, socialist, synthetic, analytical. Relative adjectives are mainly used as attributes: This wooden floor is very old. 60. The Word as a linguistic sign: its bilateral nature. [Note: by bilateral they mean with two-sides nature.] Word Structure: A word has a dual nature: material (heard or seen) and immaterial (meaning). Forms (written and oral) represent the material aspects, while meanings represent the immaterial. A word consists of at least one lexical morpheme, along with potential grammatical and lexico-grammatical morphemes. Lexical morphemes Lexical morphemes, like "book-," have more independent and specific meanings. For example, a word like "books" consists of two morphemes (meaningful parts) such as "book-" which is a lexical morpheme and "-s," which is a grammatical morpheme. Grammatical Morphemes: Morphemes like "-s" and "-ed" have relative, dependent, and indirect meanings, termed grammatical meanings. For example: words "Invites" and "shall invite" share the lexical morpheme "invite-" but differ in grammatical morphemes (-s and "shall"). - "Invites" (with bound morphemes “-s”) is a synthetic word. - "Shall invite" (with free morphemes “shall”) is an analytical word. Lexico-Grammatical Morphemes: Morphemes like "de-," "for-," "-er," "-less" are lexico-grammatical morphemes. They are bound, attached to specific lexical morphemes, and determine lexical meanings. For example, synthetic word “worker” has two lexico-grammatical morphemes “work-” and “-er” (the morpheme “-er” gives the root word “work” new meaning of profession (робота-робітник)) For example: words "Stand up," "give in," and "find out" resemble analytical words but differ from each other. "Shall" in "shall give" doesn't introduce lexical meaning, while morpheme "out" in "find out" does. "Out" is an example of a lexico-grammatical word morpheme. Prefixes vs. Suffixes: Lexical morpheme is the root, and affixes (prefixes, suffixes, infixes) are bound morphemes. Suffixes are more significant in grammatical structure than prefixes. Suffixes include both grammatical and lexico-grammatical morphemes, while prefixes are mainly lexico-grammatical. Stems: Words without grammatical morphemes, often called stems, come in four types: 1. Simple: Containing only the root (e.g., day, dogs). 2. Derivative: Containing affixes or other stem-building elements (e.g., boyhood, rewrite). 3. Compound: Containing two or more roots (e.g., white-wash, pickpocket). 4. Composite: Containing free lexico-grammatical word-morphemes or resembling a combination of words (e.g., give up, two hundred and twentyfive).