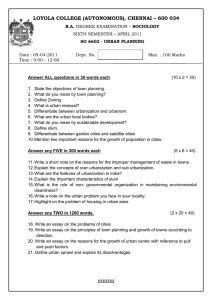

Unit 25 Urbanization Contents 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 25.7 25.8 25.9 Introduction Urban and Urbanism The Process of Urbanisation Urbanization in India Theories of Urbanisation Social Effects of Urbanisation in India Problems of Urabanisation Conclusions Further Reading Learning Objectives After studying this unit you should be able to: • Understand the term urban and urbanism • Trace the historical antecedents to urbanisation in India • Critically evaluate the theories on urbanization • Analyse the social effects and problems of urbanisation 25.1 Introduction I am sure you have heard the word urbanization and must have affair idea what it means. You probably associate it with growth of cities. Urbanization, indeed, is the process of becoming urban, moving to cities, changing from agriculture to other pursuits common to cities, such as trade, manufacturing, industry and management, and corresponding changes of behaviour patterns. It is the process of expansion in the entire system of interrelationships by which a population maintains itself in its habitat (Hawley, 1981). An increase in the size of towns and cities leading to growth of urban population is the most significant dimension of urbanization. The urban centers are essentially non-agricultural in character. In ancient times there have been great many cities such as Rome or Baghdad but ever since industrilisation and increasing industrial production and territory level production cities have grown phenomenally and now urbanization is very much apart of our contemporary life. What exactly constitutes, urban and what is the process of urbanisation will be dealt with in the following sections. We will also talk about various theories associated with urbanization. We will discuss the growth of cities and some of the problems associated with urban centers as well. 25.2 Urban, Urbanism What is an ‘urban area’? The term is used in two senses – demographic and sociological. Demographically, the focus is on the size and density of population and nature of work of the majority of the adult males. Sociologically, the focus is on heterogeneity, impersonality, interdependence and the quality of life. Tonnies (1957) differentiated between gemeinschaft (rural) and gesellschaft (urban) communities in terms of social relationships and values. The former is one in which social bonds are based on close personal ties of kinship and friendship, and the emphasis is on tradition, consensus and informality, while in the latter, impersonal and secondary relationships 116 predominate and the interaction of people is formal, contractual and dependent on the special function or service they perform. Other sociologists like Max Weber (1961) and George Simmel (1950) have stressed on dense living conditions, rapidity of change and impersonal interaction in urban settings. In India, the demographic and economic indexes are important in defining specific areas as town or city. The census definition of ‘town’ remained more or less the same for the period 1901-1951 but in 1961, a new definition was adopted. Up to 1951, ‘town’ included: 1) An inhabited locality with a total population of not less than 5,000 persons; 2) Every municipality, corporation and notified area of whatever size; and 3) All civil lines not included within municipal limits. Thus, the primary criteria for deciding whether a particular place is a town or not was the administrative set-up rather than the size of the population. Because of this definition many of the towns in reality were nothing more than over-grown villages. In 1961 ‘town’ was redefined and determined on the basis of a number of empirical tests: a) a minimum population of 5,000, b) a density of not less than 1,000 per square mile, c) three-fourths of the occupations of the working population should be outside of agriculture, and d) the place should have a few characteristics and amenities such as newly founded industrial areas, large housing settlements, and places of tourist importance and civic amenities. As a result of the new definition of ‘town’ was a reduction in the total number of towns in India between 1951 and 1961. The 1961 basis was adopted in the 1971, 1981 and 1991 censuses too for defining towns. Sociologists do not attach much importance to the size of population in the definition of city because the minimum population standards vary greatly. A city is an administratively defined unit of territory containing “a relatively large, dense and permanent settlement of socially heterogeneous individuals” (Wirth, 1938). Urban refers to a set of specialized, non-agricultural activities that are characteristic of, but not exclusive to, city dwellers. A ruling class with a capacity for taxation and capital accumulation and writing and its application to predictive sciences, artistic expression, and trade for vital materials are the kinds of specialized activities necessary to the definition of the emergence of a truly urban place (Childe, 1950). Box. 25.1 Million Cities A million city is, yes you guessed it, a city with one million (or more) inhabitants. According to the 1995 UN census these are the largest cities on the planet: 1) Tokyo (Japan) 27.2 million 2) Mexico City (Mexico), 16.9 million 3) Sao Paulo (Brazil) 16.8 million 4) New York (USA), 16.4 million 5) Bombay, India, 15.7 million The 1971 census introduced the term urban agglomeration. Very often large railway colonies, university campuses, port areas, military camps etc. come up outside the statutory limits of the city or town but adjoining it. Such areas may not be themselves qualify to be treated as towns but if they formed a 117 continuous spread with the adjoining town, it would be realistic to treat them as urban. Such settlements have been termed as outgrowths, and may cover a whole village, or part of a village. Two or more towns may also be contiguous to each other. Such towns together with their outgrowths have been treated as one urban unit and called ‘urban agglomeration’. Box 25.2 Type of Cities On the basis of broad common features of the cities we can classify them into following types: Production centres – Jamshedpur, Ferozabad, Kanpur, Kolar Centres of trade and commerce – Bombay, Madras Capitals – Delhi, Lucknow etc. Health and Recreation Centres – Mussoorie, Mysore, Kodaikanal Cultural Centres – Amritsar, Ajmer, Hardwar Diversified Cities – Vanarasi Urbanism Urbanism has been defined by various scholars as patterns of culture and social interaction resulting from the concentration of large populations into relatively small areas. It reflects an organization of society in terms of a complex division of labour, high levels of technology, high mobility, interdependence of its members in fulfilling economic functions and impersonality in social relations (Theodorson, 1969). Urbanism as way of life, Louis Wirth believes, may be empirically approached from three interrelated perspectives: • as a physical structure with a population base, technology and ecological order; • as a system of social organization with a structure and series of institutions (secondary contacts, weakening of kinship ties etc.); • as a set of attitudes, ideas and constellation of personalities (increased personal disorganization, suicide, crime, delinquency and corruption). 25.3 The Process of Urbanization Urbanization as a structural process of change is generally related to industrialization but it is not always the result of industrialization. Urbanization results due to the concentration of large-scale and small scale industrial and commercial, financial and administrative set up in the cities; technological development in transport and communication, cultural and recreational activities. The excess of urbanization over industrialization that makes it possible to provide employment for all persons coming to urban areas is, in fact, what sometimes leads to over urbanization. In India, a peculiar phenomenon is seen: industrial growth without a significant shift of population from agriculture to industry and of growth of urban population without a significant rise in the ratio of the urban to the total population. While in terms of ratio, there may not be a great shift from rural to urban activities, but there is still a large migration of population from rural areas to urban areas. This makes urban areas choked, there is lack of infrastructural facilities to cope with this rising populations. Urbanization implies a cultural and social psychological process whereby people acquire the material and non-material culture, including behavioural patterns, forms of organization, and ideas that originated in, or are distinctive of the city. Although the flow of cultural influences is in both directions – both toward and away from the city – there is substantial agreement that the 118 cultural influences exerted by the city on non-urban people are probably more pervasive than the reverse. Urbanization seen in this light has also resulted in what Toynbee has called the “Westernization” of the world. The idea of urbanization may be made more precise and meaningful when interpreted as aspects of diffusion and acculturation. Urbanization may be manifest either as intra-society or inter-society diffusion, that is, urban culture may spread to various parts of the same society or it may cross cultural or national boundaries and spread to other societies. It involves both borrowing and lending. On the other side of the diffusion coin is acculturation, the process whereby, individuals acquire the material possessions, behavioural patterns, social organization, bodies of knowledge, and meanings of groups whose culture differs in certain respects from their own. Urbanization as seen in this light is a complex process (Gist and Fava: 1933). The history of urbanization in India reveals, broadly four processes of urbanization at work throughout the historical period. These are: a) the emergence of new social relationships among people in cities and between people in cities and those in villages through a process of social change; b) the rise and fall of cities with changes in the political order; c) the growth of cities based on new productive processes, which alter the economic base of the city; and d) the physical spread of cities with the inflow of migrants, who come in search of a means of livelihood as well as a new way of life. Box 25.3 Sub-Urbanization, is closely related to over-urbanization of a city. When cities get over-crowded by population, it may result in sub-urbanization. Delhi is a typical example. Sub-urbanization means urbanization of rural areas around the cities characterized by the following features: a sharp increase in the ‘urban (non-agricultural) uses’ of land inclusion of surrounding areas of towns within its municipal limits, and intensive communication of all types between town and its surrounding areas Over Urbanization refers to the increased exemplification of the characters of urbanisation in a city or its surrounding rural area. It results due to the excessive development of urbanistic traits. Due to the expansion of the range of urban activities and occupations, greater influx of secondary functions like industry, increasing and widespread development of an intricate bureaucratic administrative network, the increased sophistication and mechanization of life and the influx of urban characters into the surrounding rural area, over urbanization gradually replaces the ruralistic and traditionalistic traits of a community. Mumbai and Calcutta are two such examples of cities. Urbanization as a Socio-Cultural Process Cities are social artifacts and stands apart from the countryside, in terms of the higher degree of its acceptance of foreign and cross-cultural influences. It is a melting pot of people with diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Seen in this light, urbanization is a socio-cultural process of transformation of folk, peasant or feudal village societies. India has a continuous history of urbanization since 600 BC. Over this period, three major socio-cultural processes have shaped the character of her urban societies. These are Aryanization, Persianization and Westernization. The Aryan phase of urbanization generated three types of cities: 119 a) the capital cities, where the secular power of the kshatriyas was dominant; b) the commercial cities dominated by the vaishyas; and c) the sacred cities, which, for a time, were dominated by Buddhists and Jains, who were kshatriyas, and later by brahmins. With the advent of the Muslim rules from the 10th century AD, the urban centers in India acquired an entirely new social and cultural character. The city became Islamic; Persian and later Urdu was the official language of state and Persian culture dominated the behaviour of the urban elite. The impact of 150 years of British rule in India, that is, Westernization, is clearly visible in various aspects of city life today – in administration, in education, and in the language of social interaction of the city people and their dress and mannerisms. Urbanism is clearly identified with westernisation. Reflection and Action 25.1 Based on your experience, what do you think is the present cultural character of city/cities in India? Do you think it is westernisation which is the dominating cultural impact or are there other influences? Write a note on this and share it with friends or fellow classmates at the study centre. Urbanization as a Political – Administrative Process The administrative and political developments have played an important role in urbanization in the past and they continue to be relevant today. From about the 5th century BC to the 18th century AD, urban centers in India emerged, declined or even vanished with the rise and fall of kingdoms and empires. Patliputra, Delhi, Madurai and Golconda are all examples of cities that flourished, decayed, and sometimes revived in response to changes in the political scene. The administrative or political factor often acts as an initial stimulus for urban growth; which is then further advanced by the growth of commercial and industrial activities. Urbanization as an Economic Process Urbanization in modern times is essentially an economic process. Today, the city is a focal point of productive activities. It exists and grows on the strength of the economic activities existing within itself. It is the level and nature of economic activity in the city that generates growth and, therefore, further urbanization. Urbanization as a Geographical Process The proportion of a country’s total population living in urban areas has generally been considered as a measure of the level of urbanization. Population growth in urban areas is partly a function of natural increase in population and partly the result of migration from rural areas and smaller towns. An increase in the level of urbanization is possible only through migration of people from rural to urban areas. Hence, migration or change of location of residence of people is a basic mechanism of urbanization. This is essentially a geographical process, in the sense that it involves the movement of people from one place to another. There are three major types of spatial moments of people relevant to the urbanization process. These are 120 a) the migration of people from rural villages to towns and cities leading to macro-urbanization b) the migration of people from smaller towns and cities to larger cities and capitals leading to metropolisation. It is essentially a product of the centralization of administrative, political and economic forces in the country at the national and state capitals. It is also a product of intense interaction between cities and the integration of the national economy and urban centers into a viable independent system. c) The spatial overflow of metropolitan population into the peripheral urban feigned villages leading to a process of sub-urbanization. It is, essentially, an outgrowth of metropolization and here there is a reverse flow of people from the city to the countryside. 25.4 Urbanization in India In this section, we will the historical background to urbanization in India and see how influential history was in the present situation of urban places and process of urbanization. Urbanization did not occur once but has recurred over and over in history as societies have urbanized at different times. It is an ongoing process that has never stopped and has rarely, showed since it’s beginning. India has long history of urbanization with spatial and temporal discontinuities. The first phase of urbanization in the Indus valley is associated with the Harappan civilization dating back to 2350BC. The two cities of Mohanjodaro and Harappa represent the climax of urban development attained in the Harappan culture. This great urban civilization came to end at about 1500 B.C, possibly as a result of Aryan invasion. The second phase of urbanization in India began around 600 BC. The architects of this phase were the Aryans in the North and the Dravidians in the South. From this period onwards, for about 2500 years, India has had more or less continuous history of urbanization. This period saw the formation of early historical cities and also the growth of cities in number and in size especially during the Mauryan and post-Mauryan eras. The Mughal period stands out as a second high watermark of urbanization in India (the first occurring during the Mauryan period), when many of India’s cities were established. The early part of British rule saw a decline in the level of Indian urbanization. The main reasons for the decline of cities during this period are: 1. the lack of interest on the part of the British in the prosperity and economic development of India, and 2. the ushering in of the industrial revolution in England. During the latter half of British rule, Indian cities regained some of their last importance; further, the British added several new towns and cities, in addition to generating newer urban forms in the existing cities. The following elements constituted the permanent components of the Indian urban system: 1. the military-political town, serving as a center for the flow of cash nexus in the society and often for the redistributive system, and 2. the temple or the full-fledged temple town. The great variations exiting among the different periods and areas developed with respect to (a) the degree of existence of a more centralized hierarchy; (b) the relative importance of coastal towns in relation to those of the hinterland and (c) the importance of temple centres and networks in relation to the more political and commercial towns. 121 Facets of British Influence on Urbanization During the 150 years of British rule, India’s urban landscape went through a radical transformation. The major contributions of the British to the Indian urban scene were: 1. The creation of the three metropolitan port cities (Calcutta, Bombay and Madras) which emerged as the leading colonial cities of the world. 2. The creation of Hill stations (Simla, Darjeeling, Mahabaleshwar etc.) and plantation settlements in Assam, Kerala and elsewhere. 3. Introduction of the Civil Lines and the Cantonments. The Civil Lines contained the administrative offices and courts as well as residential areas for the officers, whereas the Cantonments were most often built near major towns for considerations of security. 4. The introduction of the railways and modern industry which led to the creation of new industrial townships such as Jamshedpur, Asansol, Dhanbad and so on, and 5. The improvements in urban amenities and urban administration. In the British period, Indian cities became the focal points of westernisation. Schools and colleges trained boys and girls in western thought and languages. A new western oriented urban elite emerged whose dress, eating habits and social behaviour reflected western values and attitudes. With the process of westernization, there has been a concomitant alienation of the urban elite from the urban and rural masses. Urbanization in the Post-Independence Period This period has witnessed rapid urbanization in India on a scale never before achieved. The major changes that have occurred in India’s urban scene after independence are: 1) the influx of refugees and their settlement, primarily in urban areas in northern India, 2) the building of new administrative cities, such as Chandigarh, Bhubaneshwar and Gandhinagar, 3) the construction of new industrial cities and townships near major cities, 4) the rapid growth of one-lakh and million cities 5) the stagnation and decline of small towns 6) the massive growth of slums and the rural-urban fringe and 7) the introduction of city planning and the general improvement in civic amenities. 25.5 Theories of Urbanization City forms the central point of urban sociology. Like many other sociological categories, the city is an abstraction composed of concrete entities like residences and shops and an assortment of many functions. A place is legally made a city by a declaration by a competent authority. Sorokin and Zimmerman enumerate eight characteristics in which the urban world differs from the rural world. These are (1) occupation (2) environment (3) size of community (4) density of population (5) heterogeneity (6) social differentiation and stratification (7) mobility and (8) system of interactions. The study of cities was a subject that had already explored in the second part of the 19th century in early classical sociology with its celebrated dichotomies, 122 such as Maine’s (1931) distinction between status and contract and Morgan’s (1877) contrast between savagery, barbarism and civilization. This aspect was further developed by Tonnies (1957), who contrasted gemeinschaft and gesellschaft, and by Durkheim (1964), who distinguished between “mechanical and “organic” solidarity. Tonnies and Durkheim believed that the gemeinschaft type of social organization, or mechanical solidarity, is fully developed in cities, particularly in modern cities. In 1920-1940s a number of sociologist from the university of Chicago put forward ideas which for many years were the chief basis for theory and research on urban sociology. Two strands of the Chicago school that we are going to examine are the ecological approach and the ‘urbanism as away of life’ approach developed by Wirth. Louis Wirth – Urbanism as a Way of Life Wirth was one of the pioneers of the study of urbanism and his was the first systematic attempt to distinguish the concepts of urbanism and urbanization. His social-psychological theory investigates the human behaviour in an urban environment. He indicated that size, density and heterogeneity – regarded as the principal traits in defining cities – are conducive to specific behavioral patterns and moral attitudes (Wirth, 1938). For him “a city is a relatively large, dense and permanent settlement of socially heterogeneous individuals”. Urbanism is that complex of traits that makes up the characteristic mode of life in cities. Urbanism, as a way of life, may be approached empirically from three interrelated perspectives: (1) as a physical structure comprising a population base, a technology, and an ecological order; (2) as a system of social organization involving a characteristic social structure, a series of social institutions, and a typical pattern of social relationships; and (3) as a set of attitudes and ideas, and a constellation of personalities engaging in typical forms of collective behaviour and subject to characteristic mechanisms of social control. Louis Wirth shows two kinds of forces operating in urban society: the force of segregation and the melting pot effect; which has many unifying aspects like uniform system of administration etc. However, he concludes that urban society is based on a means-to-end rationality, which is exploitative and where the individual is isolated through anonymity. Wirth believed that the density of life in cities produced neighbourhoods, which have the distinctive characteristics of traditional communities. Wirth’s theory is important for it’s recognition that urbanism is not just part of a society, but expresses and influences the wider social system. However, Wirth’s observations are based on American cities, which are generalized to urban centers everywhere, where situations are different. The Ecological Approach In natural sciences the term ecology is used to understand the relationship plants and animals have with their environment. The term is used in a similar way to understand the process of urabanisation, by such scholars as Robert Park, Ernest Burgess and Amos Hawley. The scholars of ecological approach feel that cities do not grow randomly but grow along lines and in response to features which are advantageous to it–along rivers, near natural resources, in the intersection of trading rotes etc. They feel that cities become ordered in to “natural areas”, through a process of competition, invasion and succession. Patterns of location, movement and relocation in cities follow similar principles. These scholars view cities as a map of areas with distinct characteristics. Burgess sees them as concentric zones- Central Business District ( with 123 concentration of trade, retail, business and related activities are located), the Transition Zone to the outer fringes which he calls the Commuter Zone-the satellite towns and suburbs. Process of invasion and succession occur within these segments. Some of the principles of these theories can be applied to Indian situation especially to growth’s such as suburbs such as Gurgaon in outer fringes of Delhi or the growth of suburbs in Bombay but largely the theory is based on American cities which have distinct characteristics. The theory, also, underempahsises the role of planning and design in cities. Urbanism and Created Environment : Harvey and Castells More recent theorist such as David Harvey and Manuell Castell’s have stressed that urbanism is not an autonomous process, but is part of a larger political and economic processes and changes. In modern urbanism , Harvey points out space is continually restructured .The process is determined by large firms, who decide where they should open their businesses, factories etc and by policies, controls and initiatives asserted by governments which can change the landscape of a city. Like Harvey, Castells stresses that spacial form of a city is very much related to the larger process of the society. Castells further adds the dimension of the struggles and conflicts of various groups who make up the cities. He gives the example of gay community who have reorganized the structure of San Francisco city. He believes that it is not only big corporations, businesses and government which influence the shape a of a city but also the communities and groups who live in cities. Harvey and Castells analysis of uranbinasation and urabn situation adds an important dimension – the political economy of a system. Reflection and Action 25.2 According to Harvey and Castellls the special form of a city is very much influenced by the politico-economic considerations of corporations, business houses and governments. Give examples from the Indian cities to support the above statement. Indian Sociologists : Rao and Bose M.S.A. Rao (1970), analysis urabinasation and urbanism keeping in mind the larger social structures of Indian society. For him, urbanism is a heterogeneous process and hence there can be many forms of urbanisms giving rise to many types of urbanization. Rao states that the dichotomy between cities and villages is incorrect as both have the same structural features of caste and kinship and are parts of the same civilization. Moreover, urbanization and westernization are not identical and should not be confused. Urbanization does not lead to the breakdown of traditional structures of caste and joint family. The traditional and modern structures coexist in the urban milieu because of which various types of urbanisms exist – post-industrial, preindustrial, western, non-western etc. Further, urbanization is seen in relation to social change and no real social transformation is associated with it. However, due to urbanization new forms of social organization and association have emerged. Thus, for Rao, urbanization is a complex multifaceted process comprising of ideological, cultural, historical, demographic, comparative, traditional and sociological elements. Rao defines a city as a center of urbanization and urban way of life. Urbanization is a two way process. Urbanization in India is not a uniform process but occurs along different axes 124 - administrative, political, commercial, religious and educational - giving rise to several types of urbanisms. These different axes give rise to different types of contact which the city has with the villagers leading to distinct patterns of urbanization. He distinguishes three kinds of situations of social change in rural areas resulting from urbanization: villages near an industrial town, villages with a sizable number of emigrants working in towns and cities, and villages on the metropolitan fringe. Rao believed that through the study of migration, one could observe the similarities, dissimilarities and continuity between villages and towns. Rao’s sociological approach is the most complete approach to the study of urbanization because he tries to examine them in all their different facets and relate these facets to one another and to a sociological understanding of urbanism and urbanization. Ashish Bose’s demographic classification emphasizes quantitative factors like demography rather than qualitative factors in defining urbanization. For him, urbanization, in the demographic sense, is an increase in the proportion of the urban population (U) to the total population (T) over a period of time. As long as U/T increases there is urbanization. The process of urbanization is a continuing process which is not merely a concomitant of industrialization but a concomitant of the whole gamut of factors underlying the process of economic growth and social change. Bose outlines the characteristic features of urbanization in India. He made a decade-wise differentiation in terms of percentage of urbanization. Here urbanization is affected by trends in migration. He recognizes the push-back and turn-over factors of migration. He considered four variables affecting urban growth: a) Proportion of new towns to total urban population; b) Proportion of declassified towns to the total population; c) Proportion of declining towns to the total population; d) Proportion of rapidly growing towns to the total urban population. Only when these are combined, it will be possible to analyze the process of urbanization in India. Bose used the concepts of towns and cities interchangeably. 25.6 Social Effects of Urbanization in India Urbanisation has far reaching effects on larger societal process and structures. Let us capture some of these change sand effects in the following sub sections. Family and kinship Urbanization affects not only the family structure but also intra and inter family relations, as well as the functions the family performs. With urbanization, there is a disruption of the bonds of community and the migrant faces the problem to replace old relationships with new ones and to find a satisfactory means of continuing relationship with those left behind. Several empirical studies of urban families conducted by scholars like I.P. Desai, Kapadia and Aileen Ross, have pointed out that urban joint family is being gradually replaced by nuclear family, the size of the family is shrinking, and kinship relationship is confined to two or three generations only. In his study of 423 families in Mahuva town in Gujrat, I.P. Desai (1964) showed that though the structure of urban family is changing, the spirit of individualism is not growing in the families. He found that 74 percent families were residentially nuclear but functionally and in property joint, and 21 percent were joint in residence and functioning as well as in property and 5 percent families were nuclear. 125 Kapadia (1959) in his study of 1,162 families in rural and urban (Navsari) areas in Gujrat found that while in rural areas, for every two nuclear families there were three joint families; in urban areas, nuclear families were 10 percent more than joint families. Aileen Ross (1962) in her study of 157 Hindu families belonging to middle and upper classes in Bangalore found that 1. about 60 percent of the families are nuclear 2. the trend today is towards a break with the traditional joint family form into the nuclear family form into the nuclear family unit. 3. Small joint family is now the most typical form of family life in urban India. 4. Relations with one’s distant kin are weakening or breaking. Though intra-family and inter-family relations are changing, it does not mean that youngsters no longer respect their elders, or children completely ignore their obligations to their parents and siblings, or wives challenge the authority of their husbands. One important change is that ‘husband-dominant’ family is being replaced by ‘egalitarian family’ where wife is given a share in the decision-making process. I.P. Desai maintains ‘in spite of strains between the younger and older generations, the attachment of the children to their families is seldom weakened’. Sylvia Vatuk maintains that the ideal of family “jointness” is still upheld although living separate. The extended family acts as a ceremonial unit and close ties with the members of agnatic extended family are maintained. Also, larger kinship clusters including groups of bilaterally and affinally related household within the same or closely adjacent mohallas exist. There is a tendency towards bilateral kinship in urban areas. In her study of Rayapur in 1974-1976, Vatuk mentions the increasing tendencies toward individualizing the marital bond and decline of practices such as levirate widow inheritance, widow remarriage, marriage by exchange, polygyny etc. The impact of urbanization is also seen in the urban pattern of increasingly homogenized values and ways of behaving. Thus, gradual modification of the family structure in urban India is taking place such as diminishing size of the family, reduction in functions of family, emphasis on conjugal relationship etc. Kinship is an important principle of social organisation in cities and there is structural congruity between joint family on one hand and requirements of industrial and urban life on the other. In his study of nineteen families of outstanding business leaders in Madras, Milton Singer(1968) argues that a modified version of traditional Indian joint family is consistent with urban and industrial setting. Urbanization and Caste It is generally held that caste is a rural phenomenon whereas class is urban and that with urbanization, caste transforms itself into class. But it is necessary to note that the caste system exists in cities as much as it does in villages although there are significant organisational differences. Caste identity tends to diminish with urbanization, education and the development of an orientation towards individual achievement and modern status symbols. Andre Beteille (1966) has pointed out that among the westernized elite, class ties are much more important than caste ties. A noticeable change today is the fusion of sub-castes and fusion of castes. Kolenda (1984) has identified three kinds of fusion: (i) on the job and in newer 126 neighbourhood in the city, persons of different sub-castes and of different castes meet; (ii) inter-sub-caste marriages take place, promoting a fusion of subcastes; (iii) democratic politics also fosters the fusion of sub-castes. Studies of many sociologists like Srinivas (1962), Ghurye (1962), Gore (1970), D’Souza (1974), Rao (1974), have shown that caste system continues to persist and exert its influence in some sectors of urban social life while it has changed its form in some other sectors. Caste solidarity is not as strong as in urban areas as in the rural areas. Caste panchayats are very weak in cities. There exists a dichotomy between workplace and domestic situation and both caste and class situations co-exist. In respect to the change in the distribution of power, we find that in preBritish India, upper caste was also the upper class. But with education and new types of occupations, this correlation of caste and class is no longer true. Beteille (1971) pointed out that higher caste does not always imply higher class. This disharmony is most often found in the Indian cities where new job opportunities have developed. The establishment of caste association again reveals the vitality of caste system. The most powerful role that caste identity is playing in contemporary period is in politics which governs the power dimension. Caste acts as a ‘vote bank’ in both rural and urban areas and because of this, it is being revived in urban areas. Caste also becomes a basis for organising trade union like associations, which serves as interest groups which protect the rights and interest of its caste members. Certain aspects of behaviour associated with caste ideology have now almost disappeared in the urban context. The rules of commensality, or inter-dining among castes, have very little meaning in the cities. The frequency of intercaste and inter-region marriages has increased. Neighbourhood interaction in urban settlements is marked by a high degree of informality and caste and kinship are major basis of such participation. Lynch’s (1967) study of an untouchable caste, Jatavs, in Agra showed that Jatavs had well-knit mohalla (ward) organization which resembled a village community in many respects. Doshi’s (1968) study of two caste wards in the city of Ahmedabad also refers to the traditional community organization. Urbanization and Status of Women Women constitute an important section of rural urban migrants. They migrate at the time of marriage and also when they are potential workers in the place of destination (Rao). While middle class women get employed in the white collar jobs and professions, lower class women find jobs in the informal sector. Women are also found in the formal sector as industrial workers. The onslaught of forces of rapid industrialization in a patriarchal social system led men to move out in order to qualify for the labour market by acquiring specialized skills. Women were traditionally relegated to the informal and family setting. But many positive developments took place in the socio-economic lives of women as a result of increasing urbanization. Increasing number of women have taken to white-collar jobs and entered different professions. These professions were instrumental in enhancing the social and economic status of women, thereby meaning increased and rigorous hours of work, professional loyalty along with increased autonomy. The traditional and cultural institutions remaining the same, crises of values and a confusion of norms have finally resulted. The personally and socially enlightened woman is forced to perform the dual roles - the social and the professional roles (Gore (1968), Kapur (1970), 127 Ross (1983)). In the cities of India, the high level education among girls is significantly associated with the smaller family size. Though education of women has risen the age of marriage and lowered the birth rate, it has not brought about any radical change in the traditional pattern of arranged marriages with dowry. Margaret Cormack (1961) found in her study of 500 university students that girls were ready to go to college and mix with boys but they wanted their parents to arrange their marriage. Women want new opportunities but demand old securities as well. The status of urban women, because of being comparatively educated and liberal, is higher than that of rural women. However in the labour market, women are still in a disadvantaged situation. D’Souza (1963) reveals the psychological, household and social problems to which they are exposed. Reflection and Action 25.3 While women in cities have more opportunities to find employment, both as white collar workers or in the unorganized sector, they are open to more vulnerabilities than the rural women Find out from workingwomen in cities, both in organized and unorganized sector, what these added disadvantages and vulnerabilities are. Thus, while rural women continue to be dependent on men both economically and socially, urban women are comparatively independent and enjoy greater freedom. Urbanization and Rural Life Urbanization through migration to urban centres is a global phenomenon. Many migrate to cities because of the availability of jobs there. Migration has become a continuous process affecting the social, economic and cultural lives of the villagers. Rao (1974) examined the social changes in a metropolitan fringe village (Yadavpur). He distinguished three kinds of situations of social change in rural areas resulting from urbanization: 1. In villages from where a large number of people have sought employment in far off cities, urban employment becomes a symbol of higher social prestige. 2. In villages situated near an industrial town with a sizable number of emigrants working in towns and cities, face the problems of housing, marketing and social ordering. 3. The growth of metropolitan cities accounts for the third type of urban impact on the surrounding villages. As the city expands, some villages become the rural pockets in the city areas. Hence the villagers participate directly in the economic, political and social activities, and cultural life of the city. Srinivas (1962) outlined the general impact of both industrialisation and urbanization on villages. He showed how the different areas of social life are being affected by urban influences. He pointed out that emigration in South India has had a caste component as it was the Brahmins who first left their villages for towns and took advantage of western education and modern professions. At the same time as they retained their ancestral lands they continued to be at the top of the rural socio-economic hierarchy. Again, in the urban areas they had a near monopoly of all non-manual posts. Holmstrom (1969) analysed the political network of leaders in a rural pocket within the Bangalore Corporation in the context of an election. Majumdar 128 (1958) in his study of Mohana village near Lucknow, noted that the village economy is influenced by the urban market, although in an indirect way. Eames’ (1954) study of a village in U.P. showed that many emigrants have left their families behind, and they regularly send money home. Such a ‘moneyorder economy’ has enabled the dependents to clear off loans, build houses and educate their children. R.D. Lambert (1962) in his extensive review of studies concerning the impact of urban society upon village life, points out different degrees of urban influence on the rural life. Social changes are maximal in areas where displacement is sudden and substantial due to urbanization. Thus migration is a key process underlying the growth of urbanization. Far from being a mechanical process, it is governed by economic, social and cultural factors. This culture contact initiates certain processes of interaction and different modes of social adjustment in urban areas. Migration has acquired a special significance in the context of commercialization of agriculture; it has major implications for urbanization, slums ad social change; it has notable feed back effects on the place of origin, as the migrants maintain different kinds and degrees of contact, thus increasing the continuity between rural and urban areas. Many cultural traits are diffused from area one to another. Also, new thoughts, ideologies are also diffused from the cities to the rural areas due to increase in communication via radio, television, newspaper etc. Urban Politics Rao (1974) has identified four problem areas in the study of political institutions, organization and processes in the urban context: 1)Formal political structure 2)Informal political organizations 3)Small town politics and 4)Violence. There is the formal political structure, municipal or corporation government where national, regional and local political parties compete for positions of power. Lloyd Rudolph’s (1961) essay on Populist Government in Madras outlines the struggle for power in the Madras Corporation and shows the decisive dominance of the D.M.K, a regional political party. It also reveals the control exercised by the party leaders in the context of the anti-Brahmin movement and the populist support the party has acquired. The study brings out clearly the relationship between urbanization and the changing power structure. Besides formal structures of power, informal political organisations operate through caste, religious and sectarian groups, and occupational categories. Associations formed on these lines acquire political dimensions in so far as they act as pressure groups, and in some cases they even form part of organized political parties. Lynch’s (1968) study of the Politics of Untouchability describes the processes by which the Jatavs become a politically viable group in Agra city. It is significant to note that they form part of the Republican Party to compete for position of power at the city, state and national levels. A third aspect of politics in the urban context refers to the small town politics where elites, factions or ethnic groups, more than political parties, are significant in understanding the power structure. Ethnic groups get politicized and act as vote banks and pressure groups articulating their interests, and complete for various benefits of urban life. This results in a situation of conflict between ethnic groups and between the migrant ethnic groups and the locals. A.C. Mayer (1953) in his study of municipal elections in Devas in Madhya Pradesh analysed the networks and ‘action-sets’ of influential leaders. R.G. Fox (1969) showed that a Muslim-Bania conflict characterizes the politics in a small town in Uttar Pradesh. There has been a shift in the authority from the Muslim zamindars to enterprising banias (merchants). 129 Another important feature of urban politics is violence resulting from communal conflict, political disturbance, student strikes and regional armies such as the Shiv Sena in Bombay. Besides these problems of urban violence, Tangri (1962) and Kothari (1970) have drawn attention to the political implications of urbanization. Different conflict situations have arisen with the growth of urbanization such as unemployment and slums which contribute to political instability. Owen M Lynch (1980) studied the political mobilization and ethnicity among the Adi-Dravidas in a Bombay slum, who are a low-ranking caste from southern India and who have migrated to Bombay. Here, different political parties compete for their votes. One party calls on them to identify as ‘untouchables’ on all-India basis; another party bids them to remember their South Indian roots. The way in which the Adi-Dravidas define themselves politically is thus related both to their position in Bombay as rural migrants from another region and to their caste. 25.7 Problems of Urbanization The patterns of urbanization in India has been marked by regional and interstate diversities, large scale rural to urban migration, insufficient infrastructural facilities, growth of slums and other allied problems. Some of the important problems of urbanization faced in different parts of India are as follows: Housing and Slums There is acute shortage of housing in urban areas and much of the available accommodation is qualitatively of sub-standard variety. This problem has tended to worsen over the years due to rapid increase in population, fast rate of urbanization and proportionately inadequate addition to the housing stock. Millions of people pay excessive rent which is beyond their means. In our profit-oriented economy, private developers and colonizers find little profit in building houses in cities for the poor and the lower middle class, and they concentrate in meeting the housing needs of the rich as it is gainful. With large scale migration to urban areas many find that the only option they have is substandard conditions of slums. Slums are characterised by sub-standard housing, over crowding, lack of electrification, ventilation, sanitation, roads and drinking water facilities. They have been the breeding ground of diseases, environmental pollution, demoralisation and many social tensions. With India’s slum population standing at nearly 40%,slum dwellers form 44% of population in Delhi,45% in Mumbai, 42% in Calcutta and 39% in Chennai Over Crowding In major cities in India like Bombay, Calcutta, Pune and Kanpur, the population between 85% and 90% of households lives in one or two rooms. In some homes, five to six persons live in one room. Over-crowding encourages deviant behaviour, spreads diseases and creates conditions for mental illness, alcoholism and riots. One effect of dense urban living is people’s apathy and indifference. Oscar Lewis’ ‘Culture of Poverty’ (1965) was an attempt to develop a model of the behaviour of the poor in a variety of cultural settings. It is a distinct way of life that develops among the lowest stratum in capitalistic societies in response to economic deprivation and inequality. Once people adapt to poverty, attitudes and behaviours that initially developed in response to economic deprivation are passed on to subsequent generations through socialization. Water supply, Drainage and Sanitation 130 No city has round the clock water supply in India. Intermittent supply results in a vacuum being created in empty water lines which often suck in pollutants through leaking joints. Many small towns have no main water supply at all and are dependent on the wells. Drainage situation is equally bad. Because of the non-existence of a drainage system, large pools of stagnant water can be seen in city even in summer months. Removing garbage, cleaning drains and unclogging sewers are the main jobs of municipalities and municipal corporations in Indian cities. There is total lack of motivation to tackle the basic sanitation needs of the cities. The spread of slums in congested urban areas and lack of civic sense among the settlers in these slums further adds to the growing mound of filth and diseases. Transportation and Traffic Absence of planned and adequate arrangements for traffic and transport is another problem in urban centres in India. Majority of people use buses and tempos, while a few use rail as transit system. The increasing number of twowheelers and cars make the traffic problem worse. They cause air pollution as well. Moreover, the number of buses plying the metropolitan cities is not adequate and commuters have to spend long hours to travel. Power Shortage Power supply has remained insufficient in a majority of the urban centres in India. The use of electrical gadgets has increased in cites, and establishment of new industries and the expansion of the old ones has also increased dependence on electricity. Conflict over power supply between two states often creates severe power crisis for people in the city. Box 25.4 Garbage Of about 3,000 to 5,000 tonnes of garbage generated in one day in a metropolitan city, hardly 50 to 60 percent is cleared. Out of 1,500-2,000 million litres of sewage generated in a day, hardly 1,000 to 1,500 litres a day is collected. This is when the total budget of municipal corporations of cities like Delhi, Calcutta, Mumbai and Chennai varies between Rs.1,000 and Rs.1,500 crore per annum. (Source: India Today, October, 31, 1994) Pollution Our towns and cities are major polluters of the environment. Several cities discharge 40 to 60 percent of their entire sewage and industrial effluents untreated into the nearby rivers. Urban industry pollutes the atmosphere with smoke and toxic gases from its chimneys. All these, increases the chances of diseases among the people living in the urban centres. According to UNICEF, lakhs of urban children die or suffer from diarrhoea, tetanus, measles etc. because of poor sanitary conditions and water contamination. As a long-term remedy, what is needed is using new techniques of waste collection, new technology for garbage-disposal and fundamental change in the municipal infrastructure and land-use planning. All the above-mentioned urban problems are because of migration and overurbanization, industrial growth, apathy and inefficiency of the administration and defective town planning. Solutions to urban problems lie in systematic development of urban centres and creation of job opportunities, regional planning along with city planning, encouraging industries to move to backward areas, adopting a pragmatic Housing Policy and structural decentralisation of local self government itself. 131 Reflection and Action 25.4 What do you think are additional problems of urbanization, which have not been mentioned in our unit? In your opinion, what is the way out of the malaises affecting urban centres in India? 25.8 Conclusion As you can see urbanization is an on going phenomena which is very difficult to capture through any single approach or analysis, especially in India. In this unit we have tried to capture different aspects of urabnisation-the history to present situation. the various approaches to study urbanisaion and the problems and consequences of urbanization. And we find that it is a process which is linked to many larger structures and process. As globalization process is speeding up, connecting the world n unprecedented ways, there is a suggestion that cities throughout the world will come to exhibit organizational forms increasingly similar to one another as technology becomes more accessible throughout the global system Some theorists suggests that increasingly divergent forms of urban organization are likely to emerge due to differences in the timing and pace of the urbanization process, differences in the position of cities within the global system, and increasing effectiveness of deliberate planning of the urbanization process by centralized governments holding differing values and, therefore, pursuing a variety of goals for the future . 25.9 Further Reading Rao, M .S. A. (ed.), Delhi. 1974. Urban Sociology in India, Orient Longman, New Ramachandran, R., 1989. Urbanization and Urban Systems In India, OUP, Delhi. Mishra, R. P., 1998. Urbanization in India: Challenges and Opportunities, Regency Publications, New Delhi. 132