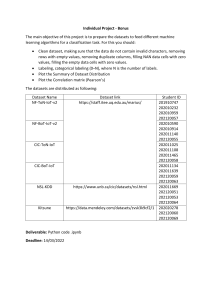

Copyright © 2021 Matthew Meyer Edited by Zack Davisson Some rights reserved. The text in this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) License. This means you are free to share, copy, and adapt the text of this book for noncommercial purposes. If you alter or build upon this work, you must distribute the resulting work under a similar license. The images in this book have all rights reserved. You may not reproduce, redistribute, or remix them without permission from the artist. www.matthewmeyer.net www.yokai.com Dedicated to the thousands of yōkai lovers from around the world who helped to crowdfund this book. There are so many of you that I had to add extra pages to the end just to fit all of your names! C Map of Japan Language Notes Introduction In the Country Tsuchinoko, Nomori, Senbiki no ōkami, Hainu, Kodama nezumi, Kyūso, Yama orabi, Yonaki ishi, Chōchinbi, Nojukubi, Tengubi, Tengu daoshi, Tengu tsubute, Tearai oni, Shikome, Oni hitokuchi, Kidōmaru, Ōtakemaru In the City Chibusa enoki, Bake ichō no sei, Igabō, Yanagi onna, Yanagi baba, Shinigami, Itsuki, Shichinin misaki, Kubikajiri, Oni no kannebutsu, Bekatarō, Dōmokōmo, Nikurashi, Jūmen, Minokedachi, Isogashi, Kame hime, Shunobon, Shitanaga uba, Nikusui, Hinoenma, Jigoku tayū, Kohada Koheiji In the House Fudakaeshi, Mekurabe, Gotoku neko, Biron, Nando babā, Fukuro mujina, Kinu tanuki, Hossumori, Mokugyo daruma, Suzuhiko hime, Oi no bakemono, Ungaikyō, Narigama, Niwatori no sō, Suppon no yūrei, Shio no chōjirō, Nebutori, Ashiarai yashiki During a Pandemic Yakubyō gami, Mikari baba, Kazenokami, Tsutsugamushi, Koshinuke no mushi, Koshiita no mushi, Subakuchū, Kamisubaku, Nakisubaku, In no kameshaku, Yō no kameshaku, Kizetsu no kanmushi, Tonshi no kanmushi, Kan no ju, Shinshaku, Kanshaku, Hōsōgami, Korōri, Hashika dōji, Amabiko, Arie, Hōnengame, Umidebito, Yogen no tori At a Wedding Kitsune no yomeiri, Yōko, Zenko, Yako, Byakko, Kokuko, Ginko, Kinko, Dakini, Ashirei, Chiko, Kiko, Kūko, Tenko, Masaki gitsune, Yao no kitsune, Otohime gitsune, Otora gitsune, Hakuzōsu, Denpachi gitsune, Keizōbō, Otonjorō, Onashi gitsune, Onji no kitsune, Shoroshoro gitsune, Osan gitsune, Okon gitsune, Kuda gitsune, Osaki, Ōji no kitsune Acknowledgments Yōkai References and Further Reading Index of Yōkai L N Japanese words can be confusing when written with Latin characters. Some letter combinations are pronounced differently than they would normally be in English. To minimize confusion, here is a brief guide on how to pronounce the Japanese words in this book. S Japanese is written with a syllabary, not an alphabet. Most syllables are made up of consonant-vowel pairs. The five Japanese vowel sounds are a, i, u, e, o. These are pronounced like the sounds in father, feet, food, feather, and foe. Each vowel receives a full syllable, as does the letter n when it stands alone. For example, the yōkai shunobon has four syllables (shu/no/bo/n). Yanagi onna has six syllables (ya/na/gi/o/n/na). D M It is common to find double vowels like aa, uu, ee, oo, ou. Some vowel combinations look awkward and make words hard to read. Other combinations like ee and oo can be mistakenly read as English diphthongs. These combinations are usually written using macrons (ā, ū, ē, ō) to make them easier to read and pronounce. For example, yōko instead of youko. Hōsōgami instead of housougami. Macrons are read with two syllables: yo/o/ko not yo/ko, and ho/o/so/o/ga/mi not ho/so/ga/mi. C W Japanese does not normally use spaces to separate words. This is not a problem when reading in Japanese, but when writing Japanese words with Latin characters it can lead to troublesome strings of letters. Words like kitsunenoyomeiri, ashiaraiyashiki, and oninokannebutsu are long and difficult to read. In this book, spaces have been inserted into some yōkai names at natural breaks to make them more legible. Written as kitsune no yomeiri, ashiarai yashiki, and oni no kannebutsu, these words are comparatively easy to read. The diacritical marks and spaces used in this book are aesthetic and meant to make reading Japanese words easier. There are numerous standards for transliterating Japanese, each with its own rules. Yōkai encountered outside of this book may be written differently. I F F Throughout history, people have invented supernatural explanations for mysterious phenomena. Strange sounds heard deep in the woods, pebbles falling from the sky, even universal concepts like good and bad luck—all were the work of spirits. Things understood in the modern world, like thunder and lightning, mental illnesses, and infectious disease were equally blamed on demons, ghosts, monsters, and mischievous magical animals. In Japan, these were collectively known as yōkai. While Japan has thousands of yōkai, one species in particular was frequently blamed for peculiar occurrences. Foxes, or kitsune in Japanese, were the usual culprit. They have a long and complex relationship with humans and play a fundamental role in Japanese folklore. Foxes live on the border of human society; always close, but never integrated like dogs or cats. They are nocturnal and rarely seen by human eyes. Still, there is plenty of evidence of their presence—broken fences, paw prints, bits of blood and dead animals mark their passage. But foxes themselves move like ghosts, silent and invisible. The notion that they can change forms helps explain this paradox. Foxes are always in our villages, moving freely among us; disguised as humans. Foxes were more than nuisances. The ancient Japanese believed mountain gods descended from their mountaintop winter homes at the start of spring, transforming into gods of the fields. Foxes emerged from the mountains at the same time, and ancients took their arrival as divine messages. Foxes were harbingers of spring, sent by the gods to prepare fields for their coming. Foxes also preyed upon pests who devoured grain, like rabbits, rats, and mice– more evidence of their link to agricultural deities. Foxes are associated with Inari more than any other god. Inari is a god of rice, sake, industry, craftsmanship, and fertility, and is one of Shintō’s most widely venerated deities. There are shrines dedicated to Inari all over Japan. It is estimated that over 30,000 shrines– roughly one third of all Shintō shrines–are dedicated to Inari. And nearly all of them have statues and other images related to foxes. Worship of Inari is decentralized and differs from place to place, but Kyōtō’s Fushimi Inari Taisha is accepted as the oldest and most important of all Inari shrines. Stories of evil foxes originated on the Asian continent in the folklore of India and China. Foxes were demons who fed upon the energy of men. They transformed into women and used sex to drain life force. Like vampires, the longer they lived the greater their powers. After a millennium of draining human lives, foxes became godlike spirits. They no longer needed to feed upon humans. Over the centuries, Chinese and Indian beliefs were brought to Japan and blended with native Japanese folklore. Both wicked and divine, these traditions combined to make Japan’s kitsune what they are today. P P Kitsune are not the only yōkai who serve as divine messengers. Other prophetic beasts have delivered news from the gods to humanity. During the late Edo period, a string of epidemics swept Japan. A growing urban population combined with an influx of foreign sailors lead to diseases like cholera ravaging the country, killing hundreds of thousands. Desperate for relief and with little understanding of diseases, people turned again to the supernatural. Epidemics were seen as the work of invisible spirits moving on the wind, infecting people as they went. To counter them, the gods sent divine messengers to warn humanity of coming troubles. These benevolent, savior yōkai came from far away, offering protection from illness. They instructed people to draw their likeness and share it with others. In the words of one such yōkai, “All who see my image shall be spared from the disease.” During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, prophetic yōkai again experienced a surge in popularity. Yōkai featured in previous books in this series such as amabie, hakutaku, and kudan—as well as other pandemic-fighting yōkai—were shared on social media. They bore the same message from centuries ago: “Spread my image and be protected from sickness.” Their ancient message seemed tailor-made for our modern culture already accustomed to sharing memes and chain letters. News outlets across the globe circulated these stories. One yōkai, amabie, emerged as a symbol of the pandemic and become a household word. Whether yōkai are truly effective against epidemics we may never be known. However, the viral spread of pandemic-fighting spirits proved that yōkai are relevant to the modern age. They retain their power to charm and capture imaginations; not just across the globe, but across the ages. T 槌の⼦ T : mallet child A : nozuchi, bachihebi, and many other regional names H : fields D : insects, frogs, and mice; also fond of sake A : Tsuchinoko resemble a mallet with no handle. Short, stumpy, and snake-like, they range from thirty to eighty centimeters long. Their scaly skin is speckled in earth tones, and they have light colored bellies. Their viper-like fangs carry deadly venom. Unlike snakes, tsuchinoko have eyelids. I : Tsuchinoko are found throughout Japan. They are active during the day from spring through fall and hibernate in winter. They nest in holes along wooded riverbanks. Tsuchinoko give off a call which sounds like “chee,” They snore when they sleep. Tsuchinoko feed on insects when they are young, switching to frogs and mice as they grow larger. Occasionally, they eat larger animals like cats or dogs. For their small size, tsuchinoko can eat large volumes of food relative. The smell of miso, dried squid, or burning hair attracts them. They are also fond of sake. Despite their awkward-looking shape, tsuchinoko are extremely nimble. Their normal movement is crawling like an an inchworm, but they can also roll sideways like a log or tumble vertically from tip-totail. They can also roll like a wheel, swallowing the tips of their tails and making their body into a circle. Tsuchinoko are great jumpers. They can spring from two to five meters in a single bound. O : Creatures resembling tsuchinoko have been part of Japanese folklore since prehistoric times. Jōmon period pottery and stone tools had motifs resembling stumpy snakes. Edo period folkloric encyclopedias recorded venomous, rolling, snake-like yōkai under names like nozuchi and tsuchi korobi. During the 1970s, a number of supposed tsuchinoko sightings and live captures sparked a “tsuchinoko boom.” People all over Japan started hunting for tsuchinoko. They became a household name as an explosion of eyewitness accounts, blurry photographs, and talk show specials enlivened the country. Since then, tsuchinoko have remained a popular subject among cryptozoologists. Monetary rewards are offered to anyone able to produce a reliable photograph or a physical specimen. Tsuchinoko are known by many regional names, such as bachihebi, dotenko, inokohebi, korohebi, tatekurikaeshi, tsuchinbo, and tsuchihebi. Nozuchi and tsuchi korobi are sometimes identified as alternate names for tsuchinoko, although they are sometimes treated as separate yōkai. N T A H D 野守 : wilderness guardian : nomori mushi, yamori : mountain forests : carnivorous A : Nomori are giant, serpentine creatures that live deep in the mountains. Their bodies are about three meters long and thick and round like barrels. They have six legs, with six toes on each foot. B : Nomori live far away from human settlements. Encounters are quite rare. They hunt by coiling their prey and strangling it like a boa constrictor. L : Long ago in Shinano Province (present-day Nagano Prefecture), a young man went deep in the wilderness into the mountains to gather firewood. He stepped on something in the undergrowth. It was a tail of a humongous snake-like creature, over ten meters long. The creature had six legs ending in six-toed feet. It was large in the middle and tapered off towards the head and tail. The creature coiled itself around the young man’s body and tried to bite his head. Fortunately, he had brought a sickle with him. He cut the creature’s throat and killed it. Afterwards, the young man carved the creature with his sickle and brought a piece home as proof. When his father saw the meat and heard the story, he became angry. The creature must have been a mountain god. Killing it was sure to bring a curse upon their family! He banished his son from his home. The son moved into a nearby small hut. Before long, the piece of meat cut from the creature began to give off a terrible odor. The smell was so foul he fell gravely ill. Unable to leave his bed, a doctor came and gave him medicine. He bathed him to wash the smell away. Almost immediately, the son began to feel better. When he told the doctor about the giant serpent, the doctor replied that it was not a serpent. It must have been a nomori. Just as yamori (geckos) are guardians of houses and imori (newts) are guardians of wells, nomori are guardians of the wilderness. A few years later, the son was chopping wood in a prohibited area of the mountains. He was caught and executed for his crime. In his village, this was said to be the nomori’s curse. S T H D 千⽦狼 : one thousand (i.e., many) wolves : mountain forests : carnivorous A : Senbiki ōkami are wolves standing on each other’s shoulders. It is usually done to hunt prey that is out of reach. Senbiki ōkami appear in legends about wolves across Japan. Folklorists consider it to symbolize wolves’ natural intelligence, athletic abilities, and tendency to cooperate in groups. While there are many variations, most follow a pattern similar to the one below from Kōchi Prefecture. L : A pregnant woman was traveling to Nahari and had to cross a mountain pass during the night. As misfortune would have it, she was struck with labor pains deep in the mountains. To make matters worse, a pack of wolves was nearby. Just then, a courier happened by. He helped the woman climb into a tree, out of reach of the wolves. He followed her into the branches to guard the woman until morning. Wolves gathered at the base of the tree. They clawed at the bark and leaped as high as they could. But they could not reach the courier and the woman. Then a strange thing happened. The wolves climbed on each other’s shoulders, forming a living ladder. The courier and the woman climbed as high as they could. One-by-one the stack grew higher and higher until the wolves could almost reach the courier and the woman. Their ladder was one wolf short. One wolf spoke: “Summon the blacksmith’s wife from Sakihama!” The other wolves howled in celebration. Before long, an enormous white wolf wearing an iron kettle as a helmet arrived. The great wolf climbed the living ladder. When it was within striking distance, the courier drew his sword and struck with all his might. There was a loud crack. His blade had split the kettle in two. The giant wolf howled in a human-like voice. A moment later, the stack of wolves vanished. When morning came and people once again appeared on the road, the courier and the woman climbed down from the tree. A passerby escorted the woman to Nahari, while the courier searched the ground where the wolves had been. He discovered a trail of blood. The trail of blood led to Sakihama, to the door of a blacksmith’s house. The courier knocked on the door and asked the blacksmith if his wife was home. The blacksmith replied that she had suffered a head injury and was resting. The courier forced his way into the house and went into the bedroom. He found the sleeping wife, drew his sword, and cut her to pieces. She turned into the corpse of a great white wolf. Digging up the floorboards of the bedroom, they discovered countless human skeletons including the bones of the blacksmith’s wife. Today in Sakihama, a memorial tower dedicated to the blacksmith’s wife still stands. They say the blacksmith’s descendants all had strangely spikey hair, like the bristles of a wolf. H ⽻⽝ T : winged dog H : forests, plains, and mountains, anywhere dogs can be found D : carnivorous A : Hainu look like regular dogs with bird wings. B : Hainu are winged dogs who can fly. Strong, fast, and ferocious, wild hainu can be as menacing as wolves. On the other hand, tame hainu can be loyal, loving pets. O : The original hainu legend comes from Chikugo, Fukuoka. In a grave at Sōgaku Temple, the hainu is supposedly buried, giving the name to the neighborhood Hainuzuka (“hainu burial mound”). A stone monument at Sōgaku Temple and several bronze statues throughout the city memorialize this local legend. The hainu was selected as Chikugo City’s official mascot. L : There are two common versions of the hainu legend–one with an evil hainu, the other a good one. Both take place in the spring of 1587 during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasion of Kyūshū when he was attempting to unify Japan. The evil hainu legend tells that long ago, a winged dog appeared in Chikugo Province. Incredibly ferocious, it attacked travelers, slaughtered livestock, and was greatly feared by locals. While passing through the area, Hideyoshi’s way was blocked by the hainu. After an intense battle Hideyoshi and his army finally slew the beast. Hideyoshi was so impressed by its cleverness and ferocity that he had the monster buried and erected a mound in its honor. The good hainu legend tells that when Hideyoshi was on his campaign, he was accompanied by a fabulous, winged dog. It loyally followed its master, flying around in the sky. Hideyoshi adored his dog. While passing through Chikugo, the hainu fell sick and died. Hideyoshi was overcome with grief. Seeing their general’s grief, his retainers built a burial mound for the hainu and interred it. It lies there to this day. K T H D ⼩⽟⿏ : small ball mouse : mountains in northeastern Japan : omnivorous A : Kodama nezumi are tiny, spherical creatures which resemble dormice. They live deep in the mountains of Tōhoku. B : Kodama nezumi are rarely encountered due to their remote habitat. However, they have one particularly noticeable behavior. Every so often, kodama nezumi swell up. As internal pressure builds, they inflate like a balloon. Then suddenly they rupture down the spine and burst. The sound of this explosion is louder than a gunshot. Everything nearby is splattered with flesh, blood, and innards. O : Kodama nezumi come from legends of the Matagi, an ethnic group of hunters who live in the mountains of northeastern Japan. They believe kodama nezumi are messengers sent by mountain gods. A kodama nezumi explosion is a warning the gods are angry. When Matagi hunters hear their distinctive popping sound, they immediately cease their hunt and head home. Anyone foolish enough to continue hunting after hearing a kodama nezumi explosion invites the wrath of the mountain gods. At the least they will have a poor catch. Worse, they might get injured. If the gods are angry enough, they might burry the insubordinate hunter in an avalanche. Some Matagi believe that kodama nezumi are reincarnated souls of hunters who foolishly defied the mountain gods’ warning. L : One cold winter night, some hunters were resting in a mountain hut. To their surprise, a woman came to the door. She begged for shelter for the night. However, the mountains were a sacred place, forbidden to women. The hunters felt they had no choice but to turn her away. The freezing woman continued wandering until she found another hut. She begged the hunters inside to give her shelter. These hunters also knew the sacred law, but they took pity. It was dangerous to roam the mountains at night, so they allowed her stay. When morning came, the woman had vanished. The hunters who allowed her to stay had a bountiful hunt. No one was injured, and they returned to their village laden with rich game. They realized the woman was a mountain goddess. She rewarded their kindness with her blessing. The group of hunters who turned the woman away met a different fate. Instead of a blessing, they received her curse. She transformed them into kodama nezumi and they were never seen again. K T A H D 旧⿏ : former rat, old rat : yōso (strange rat) : barns, houses, fields : cats, and pretty much anything else it wants A : When a mouse or a rat reaches a thousand years of age, it turns into a gigantic rodent yōkai called a kyūso. They look like ordinary rats, except as large as medium-sized dogs. B : In addition to growing larger and stronger, kyūso exhibit aggressive behaviors. Aware of their own size and strength, they no longer scurry away from danger. Instead of being chased by cats they often hunt them down and eat them. However, there are old folktales and modern urban legends about kyūso playing with cats, even raising litters of abandoned kittens as if they were their own children. More disturbing by far, there are folk tales where kyūso sneak into human beds at night to have sexual relations with young women. O : Kyūso appear in Ehon hyakumonogatari and other Edo period sources. But stories about giant yōkai rats are far older and have been a part of Japanese folklore since ancient times. There is an old saying: kyūso neko wo kamu (“a cornered rat will bite a cat”). “Cornered rat” and “old rat” are homophones in Japanese. It is possible that this yōkai’s name is a pun based on this idiom. L : A tale from 15th century Dewa Province tells of a kyūso which had taken up residence in a barn. The kyūso became good friends with a female cat who also lived in the barn. The cat got pregnant and bore a litter of five kittens. However, she died shortly after giving birth. In her place, the kyūso visited the kittens every night and took care of them. When they had grown into adult cats, the kyūso vanished from the barn, never to return. In Nagoya in the 1750s, a family was perplexed as to why their lamps were being extinguished every night. Finally, they discovered the cause: a gigantic rat came out at night and licked up the oil from their lamps. The family bought a cat to catch the rat. When night fell, they released the cat. The kyūso appeared, and the cat leaped upon it. But the kyūso was stronger. It tore open the cat’s throat. Shocked, the family searched the town until they found a bigger cat with a reputation for ratting. They purchased it, and once again released it at night. When the kyūso appeared, the two creatures locked eyes and snarled at one another. Finally, the kyūso could hold back no longer. It leaped at the cat and tore its throat open, just as it had done before. A tale from Kagawa Prefecture describes a kyūso losing to a cat. The cat was a stray taken in by a priest named Ingen from Ōtaki Temple. A huge rat weighing over 26 kilograms lived in the temple’s main building and had been terrorizing the priests for years. The cat was too small to kill the kyūso. However, after three years of living there, the cat’s tail split in two and it transformed into a nekomata. Grateful for Ingen’s kind treatment, the nekomata enlisted an army of local cats and drove the kyūso out of the temple. After a long and bloody battle, the cats finally slew the kyūso. Y T A H D ⼭おらび : mountain shouter : orabisōke : deep in the mountains : unknown A : Yama orabi are small, tree-dwelling yōkai native to Kyūshū and Shikoku. They resemble birds with over-sized heads and mouths full of sharp, pointy teeth. They are excellent mimics. B : Yama orabi are rarely seen but can be easily heard. As their name suggests, they love to shout. Yama orabi are excellent mimics and copy the voices of anyone who shouts near their homes. They shout their words back at them. While yama orabi behave in a similar way to other echo yōkai such as yamabiko and kodama, they are entirely different creatures. Yama orabi are usually only encountered deep in the mountains. They shout back any word shouted at them. More than simple annoyance, any person foolish enough to engage a yama orabi in a shouting match will be cursed to die. Superstition holds that this death curse can only be removed by ringing a cracked bell. O : The name yama orabi comes from orabu, a word in Kyūshū dialects which means to shout. L : In Fukuoka Prefecture, yama orabi are used by mothers to frighten their children to sleep. Children are warned that if they stay up too late a yama orabi will come, so they better go to sleep soon! Y T 夜泣き⽯ : night-crying stone A : Yonaki ishi look like ordinary boulders which cry like babies at night. In many cases, the stones cry because they are possessed by the vengeful spirit of a murder victim. However, sometimes it is the stone itself that cries and not a person’s spirit haunting it. The most famous yonaki ishi legend comes from Kakegawa City in Shizuoka Prefecture. B : Yonaki ishi imitate the cries of a human baby, attracting people with the sound. L : Long ago, a pregnant woman was walking home through steep mountains. She reached the Sayo no Nakayama Pass when stopped to rest. Leaning against a large round boulder to catch her breath, she was suddenly accosted by a bandit. He slashed her belly with his blade and would have cut through her if his sword hadn’t struck the boulder she rested on. The bandit robbed her and fled back into the woods. The woman bled to death against the boulder. Because the blade struck the rock, the baby was not injured in the attack. He crawled out from his mother’s body through the wound. Although the mother was dead, her soul was so worried about her child that it could not pass on. It got stuck in the boulder. From then on, every night the boulder would cry loudly. A priest from a nearby temple heard the crying. When he went to investigate, he discovered a newborn baby lying beside the boulder. The priest took the baby back to his temple and raised him, naming him Otohachi. When Otohachi grew up he was apprenticed to a sword sharpener. After many years he became an accomplish sword sharpener as well. One day, a samurai came to Otohachi and ordered him to repair a chipped katana. Otohachi asked the samurai how such a terrible crack had appeared in the blade. The samurai casually explained that the blade had been chipped many years earlier when he had accidentally struck a stone in the Sayo no Nakayama Pass. Otohachi realized that the samurai was none other than the bandit who murdered his mother. Otohachi stood up, introduced himself, and then cut down the samurai. Today, the yonaki ishi is known as one of the Seven Wonders of Shizuoka. C T A H 提灯⽕ : lantern fire : Koemonbi, tanukibi, kitsunebi : rural farmlands A : Chōchinbi are strange orbs of fire which appear on footpaths separating the rice paddies in rural villages. They hover a few feet above the ground, at about the same height and brightness as handheld paper lanterns. These lanterns, called chōchin, give the chōchinbi their name. While chōchinbi resemble other magical fireballs, their similarity to paper lanterns makes them unique. B : Chōchinbi drift about lazily, often forming long rows of dozens of lights like a string of lanterns. Occasionally they drift together and form spectral shapes that trick people. Sometimes they travel long distances from graveyard to graveyard. If a human gets too close, they suddenly vanish. O : Chōchinbi are frequently said to be the work of kitsune. Foxes use the magical fire to light their processions in the dark. They are sometimes attributed to other yōkai such as tanuki or mujina. The presence of chōchinbi is said to be a sign that yōkai are close by. L : In Nara Prefecture, these lights are called Koemonbi (“Koemon fire”). Long ago, a man named Koemon investigated a string of strange lantern lights that appeared along the riverbank on rainy nights. As he approached the lights, a fireball shot over his head. Startled, Koemon struck the fireball with his stick. The flame broke up into several hundred smaller flames which surrounded him. He ran home in terror. That night Koemon came down with a terrible fever. Within a few days, he was dead. After that, the villagers called the strange lantern lights along the riverside Koemonbi. N T H 野宿⽕ : wilderness-inhabiting fire : rural roads, mountain paths, and abandoned campsites A : Nojukubi are mysterious fires which ignite and extinguish on their own. They take the form of a thin streak of flame which appears out of nowhere. B : Nojukubi appear either in the spring following cherry blossom viewing season or in autumn after foliage viewing season. They usually appear on roadsides or in mountain hiking trails, places where humans have recently been. Just as campfires leave behind embers which smolder and glow long after the fire has died, human activity leaves behind lingering energy. Nojukubi come from this energy, flaring up suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere. Just as quickly they extinguish for no reason, even when they appear to be burning strong. They reignite and extinguish themselves over and over. Nojukubi exhibit strange qualities which distinguish them from ordinary campfire embers. They appear more frequently after rain, unhindered by dampness. They do not radiate heat or consume wood or kindling as they burn. Nojukubi do not spread like normal fire. Perhaps strangest of all, human voices can be heard having conversations or reciting poetry and songs from within the flames– echoes of whatever lively activity recently took place. O : Nojukubi appear in the Edo period yōkai collection Ehon hyakumonogatari. They were noted as a separate phenomenon from kitsunebi or Sōgenbi. Other sources describe them as a type of onibi. T T A H 天狗⽕ : tengu fire : tengu no gyorō, taimatsu maru : riversides A : Tengubi are a fiery phenomenon which appear near rivers in Aichi, Shizuoka, Yamanashi, and Kanagawa Prefectures. They appear as one or more (up to several hundred) reddish flames which float in the sky. These supernatural fires are said to be created by tengu. B : Tengubi descend at night from the mountains to the rivers. Often, they start as a small number of fireballs which split into hundreds of smaller flames. These flames hover above the water as if dancing. Afterwards, they return to the mountains. I : Humans who witness tengubi often meet with disaster–usually in the form of a serious illness contracted shortly after the encounter. Because of this, locals who live in areas with tengubi are wary. If a local sees tengubi, they immediately drop to the ground and look away. They may cover their heads with shoes or sandals. Occasionally, tengubi can be helpful to humans. During times of drought, unscrupulous farmers might steal water by redirecting neighbors’ canals into their own fields at night. This was a serious crime. However, when tengubi appeared above the canals, would-be thieves were thwarted. Either the light of the tengubi made it impossible to sneak around or the thieves’ own guilty conscious would make them run away. O : Tengubi are created by tengu who prefer the riversides over the deep mountain valleys that are their normal abode. They use tengubi as a lure for catching fish in the night. For this reason, tengubi are also known as tengu no gyorō (“tengu fishing”). Toriyama Sekien included tengubi in his book Hyakki tsurezure bukuro under the name taimatsu maru (taimatsu meaning “torch,” and maru being a popular suffix for boys’ names). He described it not as a tool for tengu fishing, but a way for them to disrupt the religious practices of ascetic monks. L : Long ago, tengubi were seen frequently in the villages of Kasugai City, Aichi Prefecture. One night, a villager was caught out in the mountains in a sudden thunderstorm. It was cold, and too dark to find his way home. He took shelter under a tree and shivered. Before long, mysterious fires appeared around him. Not only did they warm him, but they provided enough light to find the road and make it safely back to his village. Another superstition in that village was to not go outside on nights when tengubi appeared. If you did, you would be spirited away into the mountains. One night, a particularly foolhardy young man defied the superstition. He walked out of his house, faced the tengubi, and called out, “If you can take me, come and get me!” Suddenly, a large dark shape appeared out of nowhere and grabbed the young man. It picked him up and flew away into the mountains. The young man was never seen again. T T A tsuki H 天狗倒し : knocked down by a tengu : furusoma, sora kigaeshi, kara kidaoshi, tsue : forests deep in the mountains A : Tengu daoshi is an audio phenomenon heard deep in the woods. It is the sound of trees being chopped and crashing to the ground, accompanied by powerful gusts of wind. It often happens late at night and can continue for some time. I : Tengu daoshi is usually heard by people who spend most of their time in the mountains, such as woodcutters and Shugendō practitioners. It happens at night when no one would be working. Occasionally voices can be heard shouting “ikuzo!” (the equivalent of shouting “timber!” as a tree falls). Woodcutters sometimes feel their huts shake violently. However, in the morning they find no sign of fallen trees, nor any evidence of what could have made the noise. O : Tengu daoshi occurs all over Japan. It is attributed to various supernatural forces. As the name suggests, it is often believed to be the work of tengu. They make their homes deep in the mountains and are natural culprits. In addition to tengu, animal yōkai are often blamed for tengu daoshi. Some say tanuki kick rocks at humans with their hind legs and slap trees with their tails, causing these mysterious sounds. Kitsune and mujina are blamed as well. It is also sometimes said to be the work of mountain kami. Tengu daoshi is known by different regional names. Common names include sora kigaeshi and kara kidaoshi (“trees from the sky”), and tsue tsuki (“cane strike,” as it sounds like trees being struck by walking sticks). In most of Shikoku, tengu daoshi is known as furusoma, meaning “old woodcutter.” Legend has it that the phenomenon is the work of the ghost of an old woodcutter. He was illegally cutting down trees when he was crushed to death under a falling tree. His ghost now haunts the mountains, causing phantom woodcutting sounds. T T H 天狗礫 : a stone thrown by a tengu : usually deep in the mountains A : Tengu tsubute is a phenomenon where rocks mysteriously fall from the sky as if flung by an evil wind. The rocks are often invisible. After they fall to the ground, nothing can be seen where they should have fallen. When hitting water, ripples and a splash occur though no rocks can be seen. It is usually a handful of pebbles or gravel. Rarely, large boulders are hurled. Tengu tsubute is usually encountered deep in the mountains, however occasional tales of rocks raining from the sky are found in cities. I : People struck by tengu tsubute fall ill soon afterwards. Even those who merely witness this phenomenon often suffer misfortune. Hunters will not be able to find their prey. Fishers will have a poor catch. No matter how hard a person is struck by tengu tsubute no wound or mark is left on the body. O : As shown by the name, tengu tsubute is often believed to be the work of tengu. Because tengu hate the wickedness they see in humans, it is believed they throw rocks to punish the unrepentant and remind us to behave. Other yōkai such as mischievous kitsune and tanuki are occasionally blamed as well. T ⼿洗⻤ T : hand washing demon A : kyojin no ojomo (giant ojomo; a local term for monster) H : Shikoku and the Seto Inland Sea D : omnivorous A : Tearai oni are colossal beings large enough to straddle mountains. Their legs can span up to three ri–almost twelve kilometers. B : Tearai oni get their name from their unique behavior. They straddle large bodies of water and bend down to wash their hands in lakes and seas. O : Tearai oni appear in the Edo period book Ehon hyakumonogatari, which says that their actual name is unknown. The book says witnesses named them after their hand washing. Despite being called oni, the tearai oni is actually a type of giant called a daidarabotchi. In this case, oni is a catch-all term for monster. While the term tearai oni doesn’t appear before Ehon hyakumonogatari, local legends from Kagawa speak of a giant who came down from the mountains, straddled the mountains, and scooped up water from the bay with his hands to drink. Giant footprints were found high up in the mountains. This creature’s local nickname was kyojin no ojomo. It may have been the same giant as tearai oni. L : The most famous tearai oni comes from an Edo period sighting in Sanuki Province (present-day Kagawa Prefecture). The giant was seen straddling the mountains between Takamatsu and Marugame and washing its hands in the Seto Inland Sea below. S T A H D 醜⼥ : ugly woman : yomotsu shikome (“ugly woman from hell”) : Yomi (the Shintō underworld) : omnivorous A : Shikome is a broad term describing kijo, or female oni, who look like ugly human women. They have long black hair, sagging, misshapen breasts, and wide, twisted smiles. They often have bestial features such as claws, paws, pointed ears, and patches of furry hair. B : Shikome are courtesans in the land of the dead. They spend much of their time trying to make themselves beautiful. They apply thick white makeup to their faces, blacken their teeth, and wear multi-layered kimono. However, their excessive grooming only accentuates their ugliness. They are a mockery of high fashion. I : Shikome are more dangerous than most think. They are fast, able to leap a thousand ri (approximately four thousand kilometers). They are ravenous and devour food at incredible speeds. O : Shikome appear in many picture scrolls and are a popular figure in yōkai artwork. These illustrations served as the origin of a great number of yōkai. They satirize unattractive women, such as ao nyōbo, taka onna, and kerakera onna. Shikome also play a role in Japan’s ancient mythology. They are known as yomotsu shikome–“the ugly women of Yomi,” in the Shintō underworld. L : The goddess Izanami died in childbirth. Her grieving widow Izanagi journeyed into the underworld to bring her back from the land of the dead. Izanagi found her deep in the shadowy land of Yomi. He begged Izanami to return to the surface with him. But because Izanami had had already eaten the food of the dead, she could not return. But she went to beg permission from the gods of Yomi to visit him. Izanami told Izanagi to wait for her answer. She made him promise not to bring any light into the dark of the underworld. Izanagi grew impatient. He entered the palace of the dead to gaze upon Izanami’s beautiful face. Unable to see, Izanagi transformed his comb into a torch. When the light fell upon Izanami’s face, she was horrible to behold. Her flesh was rotten and covered with worms and maggots. Izanagi screamed and ran away. Izanami, indignant and betrayed, ordered her servants, the yomotsu shikome, to catch Izanagi. The shikome were faster than Izanagi. As they closed in, Izanagi threw his woven headdress to the floor, turning it into a grapevine. The shikome stopped for a moment to devour the grapes, then resumed the chase. Izanagi broke the teeth off his comb and scattered them, turning them into bamboo shoots. The shikome devoured these too, buying him just a little more time. At last, Izanagi made it to the surface. He rolled a large boulder over the entrance to Yomi, trapping the shikome and locking Izanami in the underworld forever. O T A D ⻤⼀⼝ : one bite from an oni : kamikakushi : people A : When people vanish without warning or without a trace, their disappearance is often blamed on evil spirits. There are several different words to describe this phenomenon. Someone kidnapped and taken to the spirit word is said to be a victim of kamikakushi. They might come back to the human world years later, profoundly changed by their traumatic experience. Sometimes, however, such a person never returns. The victim may be said to have been taken–or rather eaten–by an oni. Oni hitokichi describes a situation in which a person is gobbled up in a single bite and never seen again. L : A famous example of oni hitokuchi appears in the Heian period story collection Ise monogatari. Poet and playboy Ariwara no Narihira lusted after the beautiful noblewoman Fujiwara no Takaiko. Because of Takaiko’s social status, her family would never approve of their relationship. To Narihira’s dismay, their affair could only be conducted in secret. One night, the unhappy Narihira snuck into Takaiko’s room and kidnapped her. They fled into the wilderness, when suddenly a terrible storm struck. They took sheltered in a cave. Takaiko rested deep in the cave while Narihira stood guard at the entrance with his bow and arrow. By morning the storm had cleared. Narihira went into the cave to fetch Takaiko, but she was not there. The cave was home to an oni who had gobbled her up. Not even a single piece of cloth was left. Narihira had been unable to hear her screams in the night because of the storm. K T ⻤童丸 : a nickname meaning “oni boy” A : Kidōmaru is an oni who appears in Kokon chomonjū (“A Collection of Notable Tales Old and New”), a Kamakura period compilation of myths and legends. He was vicious and cruel. His father was Shuten dōji, the greatest oni of all time. Kidōmaru is best known for his attempts to avenge his father’s death. L : Kidōmaru was born after the legendary samurai Raikō (Minamoto no Yorimitsu) and his party of heroes defeated Shuten dōji’s gang and freed their captured women. Most of the women were grateful to the samurai for rescuing them and returned to their villages. However, one woman did not go home. She traveled to Kumohara and gave birth to a baby oni–Shuten dōji’s son. The boy was called Kidōmaru. He was born with a full set of teeth and an oni’s strength. By the time he was seven or eight years old he could slay a deer or a boar by throwing a single rock at it. Like his father, he was apprenticed as a temple servant at Mt. Hiei. And like his father, he was eventually expelled from the temple for being wicked. Kidōmaru fled to the mountains and took up residence in a cave. He studied magic and honed his powers in his secret hideout. He robbed travelers to survive. After years of terrorizing the mountain roads, Kidōmaru was captured by Minamoto no Yorinobu, Raikō’s younger brother. Yorinobu locked the oni in an outhouse and called for Raikō. Raikō scolded Yorinobu’s carelessness at not securing Kidōmaru in ropes and chains. He showed Yorinobu the proper way to tie up an oni. Raikō stayed over for the night to make sure Kidōmaru did not escape. But Kidōmaru was strong. He easily broke the bonds holding him. Wanting revenge upon the man who had killed his father, he snuck up to Raikō’s door. But Raikō noticed and laid a trap. In a loud voice he told his attendants that the following morning they would ride to Mount Kurama to make a pilgrimage. Kidōmaru ran ahead to Kurama to set an ambush for Raikō. On the road outside of Ichiharano, Kidōmaru slaughtered a cow and climbed inside of its body to hide. But Raikō was expecting an ambush. When he arrived at Ichiharano, he easily saw through Kidōmaru’s disguise. Raikō’s best archer, Watanabe no Tsuna, fired an arrow through the cow’s body. Wounded, Kidōmaru emerged from the cow’s skin and charged at Raikō. But Raikō was faster than Kidōmaru. He cut him down with a single strike, ending Shuten dōji’s line. Ō T ⼤嶽丸 : a nickname meaning “great mountain peak” A : Ōtakemaru is a kijin–an oni so powerful they are considered both demon and god. He is among the most fearsome yōkai in Japanese history, able to grow in size, summon storms, and wield any number of supernatural powers. Along with Shuten dōji and Tamamo no Mae, Ōtakemaru is considered one of the Nihon san dai aku yōkai, or Three Great Evil Yōkai of Japan (although some versions swap Ōtakemaru with the ghost of Sutoku Tennō). O : Ōtakemaru may be a folkloric interpretation of Aterui, a chieftain of the Emishi people of northeastern Honshu. Aterui waged a bloody war against the Yamato Japanese until his defeat and capture by Sakanoue no Tamuramaro. His legend also serves as the basis of Aomori Prefecture’s famous Nebuta Matsuri, in which large floats depicting samurai and oni are paraded through the streets. L : During the reign of Emperor Kanmu (781 to 806), an oni named Ōtakemaru terrorized travelers in the Suzuka Mountains, on the border of Ise and Ōmi Provinces. The emperor commanded his shōgun, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, to exterminate the demon. Tamuramaro raised an army of 30,000 horsemen and entered the mountains. Ōtakemaru used his magic to summon a great storm. He covered the mountains in black clouds making it impossible to see. Rains and winds battered the army. Lightning crashed and fire rained down from the sky onto the army. Tamuramaro and his men hunted Ōtakemaru for seven years but could not catch him. Frustrated by his inability to find Ōtakemaru, Tamuramaro prayed to the gods and the buddhas for help. One night he dreamed an old man told him that to defeat Ōtakemaru he must seek out Suzuka Gozen, a tennyo–beautiful female spirit–who lived deep in the Suzuka Mountains. Tamuramaro sent his army home and climbed the mountains alone. He discovered a palace in which lived a beautiful woman. She invited him inside and said, “I am Suzuka Gozen. I have come from heaven to help you defeat the demon who haunts these mountains. Ōtakemaru has the three magic swords–Kenmyōren, Daitōren, and Shōtōren. He cannot be defeated while he possesses them. But I can take them for you.” Suzuka Gozen guided Tamuramaro through the mountains to show him Ōtakemaru’s demon castle. They then returned to her palace to lay their trap. Ōtakemaru was enchanted by Suzuka Gozen’s beauty. He was determined to make her his own. Every night he disguised himself as a handsome young nobleman and traveled to her palace to court her. And every night he was denied. That night, however, Suzuka Gozen invited him inside. She told him, “A warrior named Tamuramaro is coming here to kill me. Please lend me your three magic swords so that I may defend myself.” Ōtakemaru was suspicious. He gave her Daitōren and Shōtōren but kept Kenmyōren for himself. When Ōtakemaru returned to his castle, Tamuramaro was waiting. Ōtakemaru shed his disguise, transforming into a massive oni over 10 meters tall. His eyes shone like the sun and the moon. Ōtakemaru attacked Tamuramaro with sword and spear. But the shōgun was protected. The thousand-armed Kannon, bodhisattva of mercy, and Bishamon-ten, god of war, stood by his side. A terrible battle ensued, shaking heaven and earth. Ōtakemaru divided his body into thousands of oni and charged Tamuramaro. Tamuramaro drew a single holy arrow and fired it. The arrow split into a thousand arrows which in turn split into ten thousand more. Each arrow struck home, slaying the army of oni. Ōtakemaru lunged. The shōgun was faster. Tamuramaro swung his blade and cut off the oni’s head. Tamuramaro brought Ōtakemaru’s head to Kyoto for the emperor to inspect. The emperor was so pleased that he granted Tamuramaro the province of Iga as a reward. Tamuramaro returned to Iga and married Suzuka Gozen. However, Ōtakemaru’s reign of terror was not over. His spirit traveled first to India, then returned to Japan where he possessed the sword Kenmyōren. Ōtakemaru eventually remade his body, rebuilt his impregnable demon castle on Mount Iwate, and once again terrorized Japan. Tamuramaro and Suzuka Gozen resolved to defeat Ōtakemaru once and for all. While the oni was away from his castle, Tamuramaro snuck in through a secret door that Suzuka Gozen revealed to him. When Ōtakemaru returned Tamuramaro was waiting for him. They fought, and once again Tamuramaro cut Ōtakemaru’s head off. The head flew through the air, landed on Tamuramaro’s helmet, and bit through his armor. Fortunately, Tamuramaro had prepared. He wore two helmets. Ōtakemaru bit off and swallowed the first one, but Tamuramaro was unharmed. Ōtakemaru’s head was again taken to Kyōto. It was locked safely in the treasury of the temple Byōdōin. C T 乳房榎 : breast hackberry A : Chibusa enoki was a hackberry (Celtis sinensis) which grew in Itabashi, Tōkyō during the mid-18th century. Chibusa enoki got its name from peculiar growths on it which were shaped like breasts B : The breasts of the chibusa enoki produced nourishing milk. The legend was made into a rakugyo performance during the Meiji period. L : Hishikawa Shigenobu was a samurai-turned-painter. He lived in Edo with his wife Okise and their baby boy Mayotarō. His apprentice was a skilled man named Isogai Namie. Unbeknownst to Shigenobu, Namie was a wicked man who lusted after Okise. One day, Shigenobu was called away to paint a temple ceiling. He took his servant Shōsuke with him. With his master gone, Namie threatened to kill the baby Mayotarō if Okise did not sleep with him. With no other choice, Okise relented. Gradually, Okise returned Namie’s affections. Their affair continued, but they knew it would end when Shigenobu came home. Namie devised a plan to ensure his master would never return. Namie visited Shigenobu under the pretense of observing his painting. Shigenobu was nearly finished with the temple ceiling, with only the arm of a dragon left to paint. Namie coerced Shōsuke into helping him kill Shigenobu. Shōsuke returned to the temple and invited has master to drink and watch fireflies. Shigenobu got very drunk. On their way back to the temple, Namie ambushed and murdered Shigenobu. Shōsuke ran back to the temple and reported that brigands had killed Shigenobu. However, Shigenobu was there. He had just finished painting the dragon’s arm and was signing his work. Shōsuke was so shocked that he fainted. When he awoke, Shigenobu was gone. Had he seen a ghost? Not long after that, Namie and Okise married. Shōsuke remained in Namie’s service. Namie and Okise had a baby. Even then Namie did not like raising Shigenobu’s son along with his own. He ordered Shōsuke to murder Mayotarō. Shōsuke took Mayotarō into the mountains and flung him from a waterfall. Just then, the ghost of Shigenobu appeared in the waterfall’s basin. It caught Mayotarō safely. The ghost approached Shōsuke and ordered him to take Mayotarō to the nearby temple of Shōgetsuin. Shōsuke was so shocked that he reformed his ways. He brought Mayotarō to Shōgetsuin and stayed there to raise him. A hackberry tree with bulbs on it shaped like breasts grew in the temple grounds. The tree produced sweet and nourishing milk. Mayotarō suckled on the tree and grew into a strong and healthy boy. Okise was haunted by Shigenobu’s ghost. She developed painful tumors in her breasts and could not produce milk for her and Namie’s child. The baby grew sick and died. The shock of losing both of her children caused Okise to go mad. She died in agony. The story of the boy raised by a tree spread far and wide. Soon, Namie understood what had happened. He went to Shōgetsuin to kill them. Shōsuke and Mayotarō were not skilled enough to defend themselves. However, when Namie swung his sword, Shigenobu’s ghost appeared. It guided Mayotarō’s sword hand, and Namie was struck dead. Shigenobu’s ghost was never seen again. B T A H D 化け銀杏の精 : monster ginkgo spirit : bake ichō no rei, ichō no bakemono : ginkgo trees : soil, water, sunlight A : Bake ichō no sei are spirits of ginkgo trees (Ginkgo biloba). They are tall, with bright yellow bodies the color of ginkgo leaves in autumn. They wear tattered black robes and carry small gongs. B : Bake ichō no sei appear near ancient ginkgo trees and strike gongs. It is not known whether there is some purpose to this other than making those nearby feel unnerved. I : Ginkgo trees are beloved for their beauty, resistance to fire, and wind-breaking abilities. However, superstition also holds it is bad luck to have in a home garden. Ginkgoes are high ranking, holy trees. They belong at temples, shrines, and public places–not private gardens. Planting a ginkgo in one’s own garden is almost sacrilegious. In addition, ginkgoes grow tall very quickly. They darken houses, which alters the flow of yin and yang energy and attracts evil spirits. If the roots grow underneath a house, sickness and misfortune befall the family. Residents of homes with ginkgoes die young. O : Bake ichō no sei were first depicted in an 18th century yōkai scroll by Yosa Buson. Although Buson drew the ghost of an old ginkgo tree from Kamakura, he included no other details. Later, Mizuki Shigeru elaborated on this spirit, connecting it to the old superstitions about ginkgo trees. I T A D いが坊 : unknown; possibly chestnut burr priest : uwakuchi : unknown A : Igabō have blue skin and wear baggy robes. Their most prominent feature is their jaw, which is covered in several spikey protuberances. This causes them to resemble a blowfish or chestnut burr. B : What igabō do is a mystery. We know what they look like but nothing else. O : Igabō appear in several yōkai scrolls, but only as pictures. Aside from the name, there are no stories as to what they actually do. Their name is written phonetically. leaving no contextual clues about this yōkai. The word “iga” means “burr,” and due to the resemblance with the igabō’s spikey jaw, this yōkai may be the spirit of a chestnut burr. The work “igamiau” means to snarl, and this yōkai does have a snarling face. Most likely igabō was a silly pun about a snarling chestnut burr. Y T H D 柳⼥ : willow woman : willow trees : none A : Yanagi onna are spirits which appear near willow trees late at night. They take the form of young women, occasionally carrying children in their arms. B : Yanagi onna appear to passersby on dark nights and beg for help. They resemble ghosts like ubume and kosodate yurei– motherly spirits who seek the wellbeing of their children even in death. L : Long ago, a young woman was walking at night, carrying her baby. Suddenly the wind blew strong. The woman sought shelter under a nearby willow tree. However, the fierce wind caused the long, drooping branches of the willow to whip violently. The woman became entangled in the branches. Some of them wrapped around her throat. She struggled to escape, but the branches constricted her neck tighter and tighter. Finally, she was strangled to death. Since then, a ghostly woman carrying a baby appeared under the willow tree every night, cursing the willow as she cried. W F In Japan and China, willows have been associated with femininity since ancient times. The long, flexible leaves which gracefully bend in the wind, and the curved, sweeping shape of a willow tree’s trunk were a metaphor for the ideal woman– slender, graceful, and flexible. Willows have also long been associated with yōkai and ghosts–especially ghostly women. It was believed that willows became haunted more easily than other kinds of trees. This is because spirits are trapped by a willow’s long, slender branches. When the wind blows, a willow’s branches might tenderly caress your face like a lover or wrap around your umbrella and pull it from your hands. These were said to be the work of spirits trapped in the willow. Y T H D 柳婆 : willow hag : willow trees : men A : Yanagi baba are the spirits of ancient willow trees. They take of the form of hideous old women. B them. : Yanagi baba appear beneath willows and beckon men to I : Men who approach a yanagi baba meet with a variety of misfortunes. Some are bewitched by her call and get lost in the mountains. Others trip and fall or are suddenly struck with fever. O : Willow trees that stood for a long time were thought to gain the ability to change into beautiful young women. These transformed trees lure men to their dooms. These trees were not forever young, however. Truly ancient willows turned into hideous old hags. Warnings about willow spirits were given as reminders to travelers not to be negligent or careless on the road. This cautionary tale has a double meaning. On the surface it is warning related to the superstition about ghosts haunting willow trees. Below that, it serves as a warning about the sex trade. As the willow tree is a symbol of femininity, strange willow trees calling out to men on the roads is a nod to prostitution. A man who answers the call and is led astray by such a “willow” might lose his path, his money, or worse. S T H D 死神 : death spirit : places connected with death : none; they exist only to perpetuate death A : Shinigami are spirits of the dead which possess and harm the living. It is a broad term, but in general they look like humans with a grey, corpse-like pallor, and horrifying features. B : Shinigami are drawn to death. They lurk around bodies of the recently deceased. Shinigami thrive in areas tainted by evil– especially where grizzly deaths such as murders or suicides occurred. They haunt impure areas looking for humans to possess. I : Shinigami are spirits of possession–or tsukimono– which haunt people and alter their behavior. Their victims obsess over every bad thing they have done. They become obsessed with death, culminating in a desire to commit suicide. Shinigami are particularly fond of possessing wicked people; however, anyone is fair game to a Shinigami. Those unfortunate enough to see a shinigami are doomed to unnatural and violent deaths. Many unique local superstitions deal with shinigami. For example, in Kumamoto Prefecture it is believed that anyone attending an overnight vigil with a recently deceased body will be followed home by a shinigami. Upon returning home, they must immediately have a cup of tea or a bowl of rice and lie down to sleep. Otherwise, the shinigami will possess them. O : Shinigami are related to the common folk belief that evil begets evil. If a murder or a suicide takes place in a certain area, there is sure to be another murder or suicide in that same area soon. The souls of the wicked dead call out to the souls of the living. They goad them into furthering the cycle of death. A tragedy will repeat again and again until an area is ritually purified, and the souls of victims calmed. This theme runs through ancient legends such as The Tale of the Heike, to medieval ghost stories, and even in modern urban legends and film. Unless properly exorcised, this pattern of death can continue forever. I 縊⻤ T : strangling ghost A : iki, kubire oni, chōsatsuki, chōshiki (“hanging ghost”) H : the underworld A : Itsuki are the ghosts of humans who committed suicide by hanging. B : Itsuki come from Meikai, a shadowy underworld where spirits of the dead dwell. Meikai has a fixed population. To maintain equilibrium, a soul may be reborn in the living world only when a new soul arrives to take its place. The spirits of the dead eagerly await the deaths of the living; each death brings them closer to freedom. However, there is one more rule. The circumstance of death determines who gets reincarnated next. A soul may have to wait a long time until someone dies in the same manner, freeing it to leave the underworld. Itsuki grow weary of waiting for people to hang themselves. They take matters into their own hands. I : Itsuki call out to people who are alone and command them to hang themselves. The impulse is overpowering. Even a person with no troubles or worries suddenly feels a strong desire to die. O : The fear of itsuki stretches back to ancient times. Even today people believe the dead call out to the living to kill themselves. Urban legends tell of people receiving text messages from friends joking about hanging themselves–only to learn a day later that they actually did. Suicide notes occasionally mention victims heard ghosts instructing them to do it. Often there were no warning signs or indications that the victim was suicidal. And stories about strings of suicides–where one person after another kills themself in a similar manner, with seemingly no connection to the other victims– sometimes appear in the news. Such stories are rumored to be the work of spirits like itsuki. L : A young traveler stopped at an inn. During the night, he heard a voice muttering something nearby. He peeked into the next room and saw a woman holding a noose, wrapping it around her own neck. Up in the rafters, a dark, shadowy figure was perched, cajoling the woman to kill herself. Bursting into the room, the traveler cut the rope before the woman could kill herself. The spirit vanished. Afterwards, the woman had no recollection of what she had done. One evening in Kōjimachi, Edo, a rich man held a banquet. His friend promised to help but did not show. Only after the banquet was underway did he appear–and only then to make an excuse: “I’m sorry, something came up. I stopped by to tell you I can’t make it.” He turned to leave, but the host demanded to know what was so important to make him break his promise. “I’m going hang myself from Kuichigai Gate,” he replied. He again turned to leave. Everyone at the banquet thought he had gone mad. They refused to let him leave. They held him back and forced him to drink with them. Eventually he got drunk and no longer tried to leave. Late into the banquet, news came that a man hanged himself at Kuichigai Gate. The guests were shocked. The host became convinced that an itsuki had possessed his friend. It must have grown tired of waiting for him to return from the party and convinced a different man to kill himself instead. He demanded his friend explain what had happened. His friend confessed that the night was like a dream. From what he could remember, he had made his way to Kuichigai Gate. A stranger approached him, and a mysterious voice said: “Hang yourself here and die!” For some reason he could not refuse, but he begged to be allowed to excuse himself from the banquet first. The voice agreed, but told him to promptly return and kill himself after. The host asked his friend if he still wanted to kill himself. His friend began to shake with fear and absentmindedly mimed the action of wrapping a rope around his own neck. S T H D 七⼈ミサキ : seven spirits : anywhere, but often encountered near bodies of water : none A : Shichinin misaki are ghosts found in Shikoku and Western Japan. They are always seven in number. B : Shichinin misaki appear near bodies of water, such as along the seashore or by riverbanks. They bring disaster upon any who meet them. I : People who encounter shichinin misaki die shortly after, usually in the form of a mysterious, deadly fever. Their victims join the ranks of shichinin misaki, replacing the spirit who killed them. Only then can the killing spirit find peace. This ensures that their number always remains seven. O : The word misaki (御先) means “one who goes before,” and has several meanings. One refers to the retainers and servants who travel before a noble procession. Another refers to divine animals, particularly foxes, monkeys, or ravens which serve as messengers for higher ranking spirits. Finally, it can refer to bōrei––spirits who died unnatural deaths, who are able to possess and control the living. Misaki (岬) can also refer to a cape or a peninsula. This might hint at why shichinin misaki are frequently seen near the border between land and sea. There are several theories about how shichinin misaki began. They may be the ghosts of drowning victims, explaining why they are usually encountered near water. Some describe them as the spirits of Taira soldiers who died in a boar trap while fleeing their enemies during the Genpei War. Some say they are the spirits of seven wicked priests murdered by an angry mob. Others say they are the spirits of seven women, pilgrims thrown overboard at sea and drowned. The most popular story about shichinin misaki comes from Tōsa Province (present-day Kōchi Prefecture). During the Sengoku period, Kira Chikazane was a senior retainer and nephew of Chōsokabe Motochika. During succession crisis within the Chōsobake clan, Chikazane opposed his lord Motochika. As a result, he was ordered to commit seppuku. Chikazane’s seven retainers were forced to followed him in suicide. Afterwards, strange things were reported near the graves of Chikazane and his retainers. These were attributed to the restless spirits of the seven retainers. Motochika performed rituals to appease the spirits of Chikazane and his retainers. He built a shrine in Chikazane’s name, which still stands today (the Kira Shrine in Kōchi City). However, none of this had the effect of appeasing their anger. Even today, shichinin misaki are said to haunt Western Japan and Shikoku, and Kōchi City in particular. Traffic accidents and other strange occurrences are sometimes blamed on the restless shichinin misaki. K T H D ⾸かじり : head biter : graveyards; they appear on the autumn equinox : corpses A : Kubikajiri are ghosts who feed upon the heads of the dead. They have long, disheveled hair, discolored skin, and sunken eyes. They wear white burial robes and, like most Japanese ghosts, have no legs. B : Kubikajiri appear on the autumn equinox. They lurk around graveyards looking for freshly buried corpses. When they find one, they dig it up and devour it, leaving blood and gore over the ground. O : Kubikajiri come from Ippitsusai Bunchō’s painting of a ghost eating a man’s head in a graveyard. At some point, the painting was copied, and the yōkai was dubbed kubikajiri. There are two popular explanations for how kubikajiri appear. One says that kubikajiri are created when a person dies and is buried without their head. Their corpse then turns into a yōkai and begins to haunt graveyards for a fresh replacement head. Another explanation says that kubikajiri are the spirits the elderly who starved to death. During periods of famine, family members who were a burden–such as the old or infirm–were neglected and allowed to die to reduce the number of mouths to feed. Their spirits resented this neglect and turned into yōkai after death. After the person who neglected them dies, kubikajiri dig up their grave and devour their head. O T A H ⻤の寒念仏 : oni’s winter training : oni no nenbutsu (oni’s prayers) : urban areas, along roads A : Oni no kannebutsu is an oni undergoing a monk’s ritualistic winter training. It is one of the themes of Ōtsue (“paintings from Ōtsu”), a popular genre of folk painting. B : Kannebutsu is a part of Buddhist religious training. It involves getting up before dawn on cold winter mornings to patrol the streets and loudly recite prayers. Oftentimes devotees bang a gong and visit house to house to collect alms while chanting the name of Buddha. O : Ōtsu was a major station on both the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō roads connecting Edo with the rest of Japan. A great number of travelers passed through the city. It was an important destination for religious pilgrims, home to several important religious sites, including Enryakuji, Miidera, and Hiyoshi Taisha. Ōtsue were produced by Ōtsu’s residents and sold as souvenirs and protective charms to pilgrims and travelers. These paintings were immensely popular during the Edo period. They depicted common themes, usually with moral or satirical meanings. Oni no kannebutsu is one of the most popular Ōtsue themes. Traditionally, oni no kannebutsu pictures were sold as a remedy for infant colic. An oni in monk’s garb is like a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Their horns are the manifestation of the three poisons of Buddhism which are the root of all evil: delusion, attachment, and hatred. The more we express our ego, use things for our benefit, see things through our own eyes, and act in our own self-interest, the more our horns grow. It is said oni reside in the human heart. The Ōtsue looks ready to perform winter training. He wears a monk’s robes. He carries a gong, a wooden mallet, and a donation registry. The one thing he is missing is the most important: a clean soul. Oni no kannebutsu is a satire of monks and priests who dress and act pious, but who actually behave in a manner more fitting an oni than a buddha. This comical depiction of religious hypocrisy is a theme frequently found in yōkai art. There is another hidden message in oni no kannebutsu. One of the oni’s horns is broken. In other words, the oni is trying to break free from self-delusion. The broken horn shows that it has succeeded to some degree. It serves as a role model and a reminder of the path to salvation. If an oni can try to walk the path of enlightenment, then so can anyone. B べか太郎 T : unknown; a play on the name Tarō A : bekuwatarō, bekuwabō, beroritarō, peroritarō, akanbei H : streets, alleys, and places with spare food D : everything, even people A : Bekatarō is a short, ugly yōkai with a head of matted, greasy hair and a pudgy, naked body. B : Bekatarō’s signature move is to pull down its lower eyelids with its fingers and stick its tongue out: a typical gesture of mockery in Japan. O : Bekatarō appears in several yōkai pictures scrolls under many different names. Originally, it was just an illustration. Bekatarō had no story. Nothing is known about where it comes from or why it is making such a face. Bekatarō’s backstory was created by folklorist and comic artist Mizuki Shigeru. L : Long ago, there was a baby boy with an insatiable appetite. His parents named him Tarō. He could eat as much as twenty adults would eat. His parents couldn’t afford to keep feeding him, so they abandoned him. From then on, he lived on the streets. Tarō survived by begging strangers for food. But no matter how much food he was given, it was never enough. He was always hungry. Eventually, whenever people encountered Tarō on the streets, they avoided him or even ran away in fear. Tarō’s hunger grew to be so great that he would eat anything. He began to wonder what humans tasted like. Eventually he gave in to his curiosity. He started catching people and eating them. As a result, he transformed into a yōkai. D T 右も左も : right and left A : Dōmokōmo are mysterious, two-faced yōkai who wear kimono. They appear in numerous yōkai scrolls, however there are no folk tales detailing their history or origins.. O : No story or explanation was written when dōmokōmo was first painted. Whatever its original artist intended to represent is lost to history. However, dōmokōmo is also a word with an interesting folk origin. It is an abbreviated version of the phrase dōmokōmo naranai, which means “either way you look at it, it’s impossible.” While there’s no evidence linking dōmokōmo the phrase to dōmokōmo the yōkai, they are nonetheless frequently associated with each other. L : Long ago there were two doctors named Dōmo and Kōmo. Together they were the most skilled doctors in Japan, rivaled only by each other. One day, Dōmo and Kōmo decided to have a competition to see which was the better doctor. They agreed to perform surgery on each other in front of an audience to determine who had higher skill. Dōmo went first. He surgically removed Kōmo’s arm and then reattached it. His expertise was so great that it left no scar. Afterwards, Kōmo cut off Dōmo’s arm and reattached it. Like his rival, he left no mark. Both doctors had cut and reattached so precisely that it was impossible to say who was more skillful. They elected to perform a second, more difficult competition. Instead of arms, they would cut off each other’s heads and reattach them. By this time, a large crowd had gathered to watch the spectacle. The second competition went much like the first. Kōmo cut off Dōmo’s head and reattached it. Then Dōmo cut off Kōmo’s head and reattached it. Both performed masterfully. Neither was left with so much as a tiny scar. Again, the competition could not be decided. Finally, Dōmo and Kōmo decided they would cut off each other’s heads simultaneously. The doctors prepared as the crowd watched. They cut off each other’s head at the same time. Without their heads, neither doctor was able to continue the surgery. Nobody was skilled enough to reattach their heads, and Dōmo and Kōmo died. The townspeople who had gathered to watch could only say “dōmokōmo naranai”–a pun which translated one way means “neither Dōmo nor Kōmo won.” Translated another way it means “there was no way that was going to work.” N T jealousy” 為憎 : unknown; possibly a pun meaning “hate-filled A : Nikurashi resemble human women. Their kimono hang off their shoulders erotically, exposing parts of their breasts. Their hair sensuously tumbles down their shoulders. From the neck down they are the picture of temptation. However, from the neck up they are detestable. Their faces are puckered and bloated like a catfish. Their necks are long and ribbed. Their broad ears flap like an elephant’s. Their hands are curled and clawed like a beast’s. O : Nikurashi come from Bakemono tsukushi emaki, a scroll containing twelve mysterious yōkai which are not found in other scrolls. They exist as art alone. It is likely that nikurashi was created as a joke. The name sounds like the word nikurashii, which implies hatred caused by attraction. Nikurashi may be spirits of jealousy, their own ugliness making them detest what they find beautiful. J T 充⾯ : unknown; possibly a pun meaning “grimace” A : Jūmen look like human men, except for a few key features. Their ears are wide, protruding, and somewhat elephantine. They have red rings around their eyes, giving them a bloodshot, glaring look. Their mouths are stretched wide and their lips are fat and fishy. They are mostly bald, but have bristly facial hair. O : Jūmen come from Bakemono tsukushi emaki, which does not include any information beyond a name and an illustration. Everything else about them is left to the viewer’s imagination. Their name is a mystery as well. It has no meaning as written. However, written with different kanji the word jūmen could imply a bitter or sullen grimace. It is possible the artist based this yōkai on wordplay, making a pun of its ugly, sullen face. M T A ⾝の⽑⽴ : standing-up body hair : jūjūbō A : Minokedachi look like ugly, hairy, old men. Their backs are hunched, their arms curled like claws, and their lips pursed in a pensive, unpleasant manner. Their most prominent feature is their short, bristly body hair which grows all over and stands up on end. B : Nothing is known about about minokedachi’s behavior, but they look like someone who can’t help but complain about every little thing. I : There is little writing about minokedachi that still exists. It is unclear what they do. Some believe they cause those whom they possess to whine and gripe incessantly. Another theory is they may be spirits of fear or cowardice, exemplified by their hair standing on end. O : Minokedachi appear in several yōkai picture scrolls, such as Hyakki yagyo emaki, and Bakemono tsukushi emaki. Like many picture scroll yōkai, these pictures are the only record of their existence. No stories or written descriptions exist. Their true nature is up to the imagination. I T A いそがし : busy : human-inhabited areas A : Isogashi are blue-skinned monsters with floppy ears, big noses, and massive tongues which wag from their mouths. B : Isogashi run about frantically, as if there were a million things they need to do. I : Isogashi are tsukimono–a type of yōkai which possess humans and influence their behavior. Humans possessed by isogashi become restless and unable to relax. They constantly move about. Sitting around and doing nothing makes them feel as if they are doing something wrong. O : Isogashi first appeared as a nameless yōkai in the Muromachi period picture scroll Hyakki yagyō emaki. They do not appear in folklore or legends. This painting spawned two different yōkai. During the Edo period, the monster was copied with isogashi written beside it into an anonymous picture scroll. No other description was given besides the name. This was copied by several other picture scrolls, keeping the yōkai labeled as isogashi. Around the same time, Toriyama Sekien took the nameless yōkai from the original Hyakki yagyō emaki illustration and included it in his book Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. He named it tenjōname, the ceiling licker. Isogashi had a name but no story until the Shōwa period. Mizuki Shigeru gave the yōkai an origin as a spirit which possesses humans to make them feel restless. K T H ⻲姫 : turtle princess : Inawashiro Castle A : Kame hime is a spirit who haunted Inawashiro Castle in Fukushima Prefecture. She is the younger sister of Osakabe hime, a spirit who haunts Himeji Castle. B : Kame hime is a reclusive yōkai. She rarely appears before people. When she communicates, she does so through other yōkai in her service, such as shunobon and shitanaga uba. O : Her name comes from Inawashiro Castle’s nickname: Kameshiro (turtle castle). Inawashiro Castle was destroyed in 1868 during the Bōshin War. Today, nothing remains but the castle’s stone foundations. L : Kame hime first appeared in 1640, when Katō Akinari was the lord of Inawashiro Castle. His chamberlain, Horibe Shuzen, was in charge of the castle’s defenses. In December, Horibe Shuzen discovered a child he had never seen before running through the castle. The child turned and said, “Hey! You have not introduced yourself to the ruler of this castle yet. My lord is receiving visitors today, so hurry and pay your respects!” Shuzen was flabbergasted. “Impudent child! How dare you! Katō Akinari is the only lord of this castle. And I am his chamberlain!” The child laughed. “You’ve never heard of Osakabe hime of Himeji? Or of Kame hime of Inawashiro? Then you are already doomed.” Saying this, the child vanished. There was no sign of the child for some time. However, on New Year’s morning, when Shuzen joined the other retainers in the castle’s hall, a coffin and funeral instruments had been placed at his seat. He demanded to know who had put them there but none of the retainers had any idea. That night, Shuzen was awoken by the sound of people pounding mochi echoing throughout the castle. A few days later, Shuzen collapsed in the castle’s toilet. Two days after that, he was dead. Later that summer, a seven shaku (2.1 meters) tall ōnyūdō–a giant– was spotted collecting water by the rice fields just outside of the castle. Soldiers chased after it and cut the giant down in a single stroke. When they examined the body, they saw that it was a huge mujina–a shape-changing badger. Henceforth, there were no more strange occurrences at Inawashiro Castle. S T A H D 朱の盆 : scarlet tray : shunoban, shuban, shunobanbō : dark, lonely roads and buildings : carnivorous A : Shunobon are ferocious demons from the mountains of Niigata and Fukuoka. They have bright red skin and wear priest’s robes. Usually depicted with a single eye that glows like lightning, two-eyed shunobon also exist. Shunobon can grow up to 1.8 meters tall. Their heads are large in proportion to their bodies, with hair resembling long needles and mouths stretching from ear-to-ear in terrifying grins. When they gnash their fangs, it sounds like thunder. B : Shunobon are masters of psychological horror. Their primary activity is frightening unsuspecting humans, revealing their horrifying faces with exquisite timing. People who see a shunobon usually faint or even die from sheer fright. I : Shunobon usually work alone, but they occasionally cooperate with other yōkai. In some stories they help shitanaga uba capture humans to eat. Shunobon are also shown in the service of powerful yōkai like Kame hime and nurarihyon. O : Shunobon’s name refers to their large heads, which resemble broad trays. Their name was originally shunoban, however when Mizuki Shigeru portrayed them he changed their name to shunobon. Due to the popularity of Mizuki’s work, this became the common spelling of this yōkai’s name. L : Long ago, a young samurai was traveling alone through Aizu. He heard that monsters haunted this road, so he was afraid when the dark of evening fell. Not far ahead, he spotted another samurai walking in the same direction. He quickened his pace to catch up so he wouldn’t have to walk alone. The two men chatted about this and that, until finally they arrived on the subject of monsters. “I’ve heard that a creature called shunobon appears on this road at night. Have you heard this legend?” asked the young samurai. The other turned to him and said, “Does he look something like this?” As the samurai spoke, his skin became as red as blood. His hair grew into spikes and his eyes glowed like the stars. His mouth split from ear to ear revealing a row of razor-sharp fangs! The young samurai was so frightened that he fainted right in the road. Sometime later, he awoke. The monster was nowhere to be seen. The young samurai ran as fast as he could down the road, stopping at the first house he saw. When the woman who lived there saw the terror in the poor samurai’s eyes, she invited him inside. As he settled down, he told the woman about his horrible encounter. The woman consoled him. “You poor thing! What a horrible sight to see alone on the road. By the way, did the monster look something like this?” Her face transformed into the shunobon he had seen earlier. The samurai ran screaming from the house. He ran all the way back to his own home and hid in his futon. He was too scared to leave. After one hundred days, he succumbed to his fear and died. S T H D ⾆⻑姥 : long-tongued old woman : isolated hovels deep in the mountains : carnivorous, especially human flesh A : Shitanaga uba look like elderly women. They have extremely long tongues which can be over 1.5 meters long. B : Shitanaga uba live in dilapidated hovels deep in the mountains. They feed on lost travelers by licking the flesh and blood from their bodies. I : Shitanaga uba are known to cooperate with other yōkai–shunobon being the most famous example. They can also be found in the employ of powerful spirits such as Kame hime. L : One cold autumn evening, two men traveling from Echigo to Edo found themselves lost in the mountains. Night was approaching fast. Up ahead they spotted a lonely, crooked, old cottage alongside the road. They knocked on the door of the cottage and begged for shelter for the night. An old woman in her seventies was inside, spinning cloth from ramie. She welcomed the two men into her hovel and did her best to make them comfortable. She put dried leaves into the hearth to start a fire and boiled water to make tea. The two men were grateful for the simple hospitality. Soon they fell asleep. One of the travelers awoke from his slumber feeling strange. Squinting into the darkness, he saw the old woman leaning over his traveling partner, licking his face with an impossibly long tongue. Startled, the man coughed. The old woman slid back over to the hearth and resumed spinning ramie. A moment later there was a gruff voice at the window. “Oi, shitanaga uba! It’s shunobon. What’s taking you so long? Let me give you a hand.” A monster entered the hovel. It stood almost two meters tall and had a large scarlet face that resembled a lacquered tray. The traveler drew his sword and jumped at the monster. As he slashed, it vanished into thin air. The old woman grabbed the sleeping man and ran out the front door. A moment later, the entire hovel vanished. The traveler found himself in the middle of an abandoned field. Alone, helpless, and lost in the dark, the man huddled among the roots of a tree and waited until dawn. When the sun rose, there was no sign of the hovel or the old woman. In a thicket nearby, he discovered the remains of his traveling companion: a bleached white skeleton, licked completely clean. N T H D ⾁吸い : meat sucker : mountain roads between Mie and Wakayama Prefectures : human meat; especially that of young men A : Nikusui are vampiric monsters which hunt men late at night on mountain roads. They usually appear as beautiful women about 18 or 19 years old. B : Nikusui prey upon men traveling alone by lantern light. They come from out of the darkness and flirtatiously ask to borrow a lantern. When they get close enough, they snuff out the light. In the pitch dark, they bite their victims and suck the meat from their bodies. They leave nothing behind but skin and bones. Occasionally nikusui approach men in their bedrooms, seducing them and exhausting them with sex. Then they suck the meat from their prey at their leisure. I : To protect against nikusui, villagers along border between Mie and Wakayama Prefectures avoid going out at night. Those who absolutely must travel through the mountains at night protect themselves by preparing spare lanterns and burning coal. If a nikusui steals their lantern, they can throw lit coals at them to keep them away. O : Stories of nikusui are cautionary tales, warning men to keep away from strange women. A beautiful woman could figuratively “snuff out a man’s fire,” by draining his wealth and energy, and distracting him from more important things. Long ago people believed in jinkyo–a sickness caused by loss of semen. Overindulgence in sexual activity was believed to drain a man of his power, leaving him weak and anxious. Losing too much semen could be lethal. Thus, sexual promiscuity in men was frowned upon not only for social reasons, but for health concerns too. Nikusui represent the many dangers of overindulging in lust. L : A man named Genzō was hunting late at night on Mt. Hatenashi. Suddenly, a beautiful woman 18 or 19 years old appeared and giggled. Oddly, she carried no light even though it was quite dark. She asked to borrow Genzō’s lantern. Genzō had a bad feeling. He carried a bullet inscribed with a prayer to Amida Buddha. He loaded the bullet into his rifle and threatened to shoot the girl. She fled into the darkness. Genzō continued on his way. A short time later, a terrible monster over six meters tall charged out of the darkness at him. Genzō fired his rifle with the blessed bullet. The monster fell, and Genzō was able to get a closer look at its true form. It was a bleached white skeleton inside a loose bag of skin, with no meat at all. H T A H D ⾶縁魔 : flying fate demon : enshōjo (fate hindering woman) : human-inhabited areas : men, especially clergy A : Hinoenma are femme fatales of the yōkai world. It is an allegorical term warning about the dangers of beautiful women. East Asian folklore is full of tales of women who used their charms to destroy important men. The collapses of three of China’s dynasties are attributed to such women. Mo Xi was said to be responsible for the collapse of the Xia Dynasty, Daji for the Shang Dynasty, and Bao Si for the Western Zhou Dynasty. B : Hinoenma use their beauty to destroy men–especially good, upstanding men like monks. They feed on virility and lifeblood, causing their victims to become poor and weak. In the end, their men die and hinoenma move on to new victims. O : Hinoenma literally means “flying fate demon.” Fate in this case is the Buddhist concept of nidana–the cause-and-effect chain which links all things and leads to the cycle of reincarnation. Fate demons are creatures from Buddhism which disrupt a person’s spiritual progression. This is a reference to Mara, the demon king who tried to block the Buddha’s quest for enlightenment by tempting him with beautiful women. Sex was sinful to clergy because it was a worldly, carnal activity which distracted from the path of spirituality. Phrases like “bodhisattva on the outside, yasha on the inside” were meant to remind monks that no matter how pleasing a woman looked, her true nature was that of a demon. Women were dangerous to men’s wealth and status–eating their food, spending their money, and driving them into financial, social, and spiritual ruin. Lust being a barrier to spiritual enlightenment, it caused men to focus on carnal desire and worldly things. Under the spell of lust, men craved material wealth to maintain the extravagant lifestyles women demand. In other words, give a woman your heart and she’ll take your soul. Hinoenma can also mean “fiery Enma,” referring to the king of hell–a hint at the punishment for monks tempted by women. The name also evokes hinoe uma–the year of the fire horse–an event which occurs every 60 years in the Chinese calendar. Women born in these years are destined to bring ruin to others. L : Yaoya Oshichi was born in Edo in 1666, the year of the fire horse. In 1681, a great fire ravaged the city. While watching the conflagration, Oshichi spotted a handsome temple page named Ikuta Shōnosuke. She fell in love at first sight. Hoping to see him again, the following year she attempted arson. She was caught and was burnt at the stake for her crime. Since then, it has been believed that women born in the year of the fire horse are destined to have hot tempers and ruin their husbands by consuming all they own. This superstition continues today. The most recent year of the fire horse, 1966, saw a 25% drop in births compared to the previous and following years. Weddings have even been canceled by superstitious families after discovering that the bride was born in the year of the fire horse. J T 地獄太夫 : hell courtesan A : Jigoku tayū is a legendary figure from 15th century Sakai, Ōsaka. Her story appeared during the Edo period, when novels and art depicting life in the red lightred-light districts were popular. Jigoku tayū’s legend is intertwined with Zen master Ikkyū. Eccentric and iconoclastic, Ikkyū is one of Japanese Buddhism’s most influential figures. Jigoku tayū attempts to corrupt him while he attempts to save her. L : Long ago lived a young girl named Otoboshi. She was the daughter of a samurai. When her father was killed, she fled with her family into to Mount Nyoi. They were ambushed by bandits and Otoboshi was kidnapped and sold to Tamana, a rich brothel owner in the Takasu pleasure district of Sakai. She was trained to become a yūjo–an upper-class courtesan. Otoboshi grew into a beautiful, intelligent, and sharp-witted woman. Although her life had been full of misfortune, she believed it was the result of karma–sins committed in past lives. She took the name Jigoku (“Hell”) to mock her misfortunes. She wore kimono decorated with skeletons, fire, and scenes of hell. But in her heart she constantly recited the name of Buddha. She hoped to be freed from her terrible karma. Jigoku’s grace, beauty, and wit distinguished her from the other yūjo. She spoke with elegance. She recited poetry with unrivaled skill. Her unique name stood out from her competition, who had flowery names like Hotoke gozen (“Lady Buddha”). Jigoku quickly rose to the rank of tayū, the highest possible rank for a yūjo. Those who saw her were instantly charmed. Her beauty intimidated even the most pompous patrons. Cocky clientele who tried to best her in poetry contests were humiliated. She was the talk of the town. The hell courtesan was as brilliant as she was beautiful; as sarcastic as she was seductive; as terrifying as she was tempting. Word of this captivating courtesan caught the attention of the Zen monk Ikkyū. He visited Takasu and went to the Tamana brothel to meet the courtesan he had heard so much about. When Ikkyū appeared at the brothel, Jigoku recited a poem: Sankyo seba miyama no oku ni sumeyokashi Koko ha ukiyo no sakai chikaki ni If you live in the mountains It is best to stay Deep in the mountains This place is close to the border Of the floating world Her multi-layered poem was rich in metaphor and wordplay. Ikkyū did not miss Jigoku’s implication. She asked what a monk like him was doing in a pleasure district. Why step into a place of sin and attachment from which Buddhists seek refuge? Intrigued, Ikkyū replied with a poem of his own: Ikkyū ga mi wo ba mi hodo ni omowaneba Ichi mo yamaga mo onaji jūsho yo As for Ikkyū This body I have Means nothing to me A city and a mountain retreat Are both the same place He implied that a Zen priest has no attachment to his body. To the enlightened, the body does not truly exist. Nor is there any intrinsic difference between a brothel and a temple. They are one and the same. Ikkyū suspected he had found the hell courtesan. He began another poem: Kikishi yori mite otoroshiki jigoku ka na Seeing hell in person Is much more terrifying Than hearing about it Jigoku understood Ikkyū’s meaning. He had come to see the famous courtesan. He complimented her terrifying beauty and wit and asked if she was Jigoku. Jigoku answered by finishing his poem: Shi ni kuru hito no ochizaru ha nashi There is none who dies Who does not fall into hell Her poem played on Buddhist themes while boasting that all who come for her companionship fall madly in love with her. Jigoku was intrigued by the odd monk and invited him into the brothel. She offered him a vegetarian meal appropriate for a monk. He refused and instead asked for sake and carp. Monks were forbidden from indulging in alcohol, meat, and sex, so Jigoku grew suspicious. She sent girls to Ikkyū’s room to test his character. The girls sang, played drums and flute, and danced for Ikkyū. The monk reveled in their entertainment and even joined in. Jigoku observed secretly from the next room. Then she noticed something odd about the shadows they cast on the paper doors. She peeked into the room and saw that the dancers had becomes skeletons. Their white bones cavorted to the music. She entered the room, but as soon as she did, everyone turned back to normal. Ikkyū partied until he passed out. In the middle of the night the monk awoke and went to the veranda. Jigoku watched as Ikkyū, having indulged too much, vomited into the pond. When his vomit hit the water, it turned back into a live carp and swam away. The following morning Jigoku told Ikkyū what she saw the previous night. She asked if she had been dreaming, or if she had really seen dancing skeletons. Ikkyū answered her with one of his most important teachings: “When are we not dreaming? When are we not skeletons? We are all just skeletons wrapped with flesh patterned male and female. When our breath expires, our skin ruptures, our sex disappears, and superior and inferior are indistinguishable. Beneath the skin of the person we caress today, there is no more than a skeleton propping up flesh. Think about it! High and low, young and old, male and female: we are all the same. If you awaken to this one basic truth, you will understand.” Jigoku vowed to change her life and become a nun. Ikkyū refused her. He told her to remain a courtesan. He told to find her own form of enlightenment; that religion was hypocritical; and that a yūjo was more worthy than a nun. Jigoku became Ikkyū’s student. She remained in her brothel and Ikkyū visited her time and time again to meditate and pray together. Jigoku came to understand that all people are merely skeletons in bags of flesh. She found peace. She continued to work as a courtesan while studying and praying every day. She gave her earnings generously to charity. Jigoku eventually achieved enlightenment. Like most courtesans, Jigoku died at a young age. Ikkyū was by her side at her death. Her final words were a poem which expressed her last compassionate wish: Ware shinaba yakuna uzumuna no ni sutete uetaru inu no hara wo koyase yo When I die Do not burn me or bury me Throw me into a field So that I may feed The starving dogs Ikkyū laid her to rest in a field as she wished. He then built a grave for her nearby in the temple Kumedadera in the village of Yagi. K T K ⼩幡⼩平次 : none; this is his name A : Kohada Koheiji is an Edo period ghost connected to the theater. The events that inspired his story transpired around 1700, however nothing was written down until a hundred years later. In 1803, Santō Kyōden wrote Fukushū kidan Asaka no numa (“The Strange Tale of Revenge from Asaka Swamp”). Kohada Koheiji’s story was adapted into a kabuki play shortly after that. B : Kohada Koheiji’s ghost jealously guards its status as the best ghost actor ever. To this day, actors who perform adaptations of his story are haunted by strange occurrences, suspicious accidents, and even inexplicable injuries. L : During the time when Ichikawa Danjūrō II commanded the stage, there was a third-rate actor named Kohada Koheiji. He studied under master Unagi Tarōbē and was part of the Moritaza theater troupe. Koheiji was a terrible actor and an unattractive man. He had pale skin, sunken eyes, and matted hair. He had trouble landing even the smallest roles in any of Edo’s kabuki productions. Koheiji was married to a woman named Otsuka. She was the widow of Ikushima Hanroku, a disgraced actor who was executed for stabbing and killing the great Ichikawa Danjūrō I on stage. Koheiji loved Otsuka deeply, but she was embarrassed by him and thought him a fool. Koheiji’s manager felt sorry for him. He resorted to begging and bribing producers to find something, anything, for the struggling actor to perform. Finally, he landed a part for Koheiji with a traveling show in the countryside. Audiences were far less picky than in the capital. Because his sickly appearance meant the producers could save money on makeup, Koheiji was cast as a ghost. Koheiji believed this was his last chance to make it as actor. He did everything he could to make his performance believable. He studied the faces of dead, making note of the way their muscles hung limp and eyes stared blankly. He copied their rigid, lifeless poses. He practiced speaking in a haunting voice and walking with eerie grace. His hard work paid off. Koheiji’s ghost performance was widely acclaimed, and he suddenly found himself the talk of the countryside. The other actors in his troupe finally admitted that Koheiji was a great actor, even if only in the role of a ghost. While Koheiji was away acting in the countryside, Otsuka fell into the arms of another performer in the Moritaza–a taiko player named Adachi Sakurō. Sakurō stayed in Koheiji’s house in Edo with Otsuka and pretended to be the master of the house. Eventually, Otsuka asked Sakurō to get rid of Koheiji once and for all so that they could be together forever. At the time, Koheiji was performing in rural Asaka (in present-day Fukushima Prefecture). Sakurō’s brother, a bandit named Unpei, lived nearby. Sakurō decided to have Unpei help get rid of Koheiji. Sakurō traveled to Asaka, where Koheiji was surprised and delighted to have a Moritaza troupemate join his performance. Sakurō played the drums while Koheiji did his ghost act and the audience was highly entertained. The local magistrate awarded Koheiji a sum of five golden ryō for his performance, a very gracious sum. Between performances, Sakurō and Unpei planned the murder. One day the performance was canceled due to rain. Sakurō invited Koheiji to a swamp to go fishing. Far from observers, Sakurō struck Koheiji with his fishing rod and pushed him into the water. Then he held Koheiji’s head under until he drowned. Koheiji’s body sank to the bottom of the swamp. Sakurō went to Unpei’s secret hideout. Unpei met him there and informed him that their “guest” had arrived and was in the next room. Sakurō peeked into the room where Koheiji’s waterlogged corpse was lying on the floor. “How did he get here?” asked Sakurō. Unpei answered that it was already there when he arrived. Sakurō searched Koheiji’s body and found the five golden ryō. “Hah! Now his money and his wife are mine!” Suddenly, Koheiji’s body rattled and rolled over. He grabbed Sakurō’s wrist with hands as cold as ice and strong as iron. Sakurō screamed. He tried to break free, but its grip was too tight. He yanked his arm harder and harder until the corpse flopped on top him. Koheiji’s eyes popped open, and his gaze locked onto Sakurō. Unpei heard Sakurō’s scream and rushed in. The corpse had pinned his brother to the floor, its eyes blazed in a vengeful stare. Sakurō was paralyzed with fear. Unpei tried to pull the corpse off his brother, but it wouldn’t budge. Unpei drew his sword and lopped off Koheiji’s head with a single stroke. The head rolled across the room, but the body still gripped Sakurō’s wrist tightly. Unpei had to cut each of Koheiji’s fingers off one-by-one to free his brother. Sakurō jumped up and ran. He didn’t stop until he reached Edo. Sakurō arrived at Otsuka’s residence and called for her. In a panic, he told her everything that happened: the murder; the ghost; the icy cold grip of the corpse and its hateful eyes. Otsuka was bewildered and said, “Koheiji just came home a little while ago. He’s resting in the back room.” Sakurō could not believe it. He crept towards the room where Koheiji was said to be sleeping. When Sakurō entered the room, he saw a body lying behind a folding screen. He reached to pull the screen back, but a pale, blue hand grabbed the screen and held it fast. Sakurō pulled as hard as he could. Pop! Five severed fingers rolled around on the floor and instantly began to rot. Sakurō and the folding screen crashed to the floor. The smell of death filled the room. But there was no body. A tiny flame floated up into the air and flew out the window. While Sakurō was terrified, Otsuka was undisturbed. She was just relieved that Koheiji was dead. She arranged for a funeral. And then for a wedding. Half a year passed. Sakurō and Otsuka lived as husband and wife. They forgot about Koheiji altogether. Then one night, Sakurō awoke to find another man in bed between him and Otsuka. He leaped to his feet in a rage, but there was no one there. That moment, Sakurō began to doubt Otsuka’s fidelity. Their love started to fracture. One night while returning home from drinking, Sakurō saw a figure climb into his bedroom window. He peeked inside and saw a man in bed with Otsuka. Drunk and enraged, he drew his sword and ran into the house. Otsuka awoke in a panic and, without thinking, raised her hand in defense. She grabbed the sword’s blade and all five of her fingers were severed. They fell to the floor and rotted away, filling the room with the smell of death. The stranger was nowhere to be seen, but a cackling laugh came from above them. It was Koheiji’s voice! Otsuka fell to the floor in shock. Every night, Koheiji’s ghost returned to haunt them. Sakurō and Otsuka lost their minds. In life, Koheiji had perfected his ghost act so perfectly it was indistinguishable from the real thing. In death, Koheiji’s performance was even more terrifying and sublime. The haunting drove Otsuka deeper into madness. Otsuka’s treatments cost them nearly everything they owned– including the five golden ryō Sakurō had stolen from Koheiji. Otsuka never recovered. She suffered and died in madness. Sakurō gave his last coins to a priest for Otsuka’s funeral, but the priest was a con artist. He ran off with Sakurō’s money. Penniless and driven to insanity, Sakurō lived as a beggar. One day, he saw a priest who resembled the conman who had stolen his money. Sakurō screamed and attacked the priest. The priest beat Sakurō with his staff, knocking him off the road and into a pond. Bruised and soaked, Sakurō came to his senses. He crawled out of the pond to apologize, but the priest struck him over and over, beating him nearly to death. Finally, some strangers broke up the fight. They took Sakurō back to his house to rest, but his wounds were severe. He fell into a feverish insanity. He cried out in his delirium all night long. He never woke up. When his neighbors found him the next day, his body was bloated and discolored–like that of a drowned corpse. Sometime later, the great Ichikawa Danjūrō II heard the tragic story of the famous ghost actor Kohada Koheiji’s murder. He pitied Koheiji and offered up prayers for his soul. As Danjūrō prayed, the wet and bloated ghost of Koheiji appeared and drifted towards the acclaimed actor. Danjūrō glared at the apparition. “Koheiji. You really do make a fantastic ghost.” With those words of recognition, Koheiji’s ghost seemed to find peace and disappeared. F T A H D 札返し : fuda (charm) returner : fudahegashi (“charm ripper”) : homes, temples, and areas protected by charms : none A : Fudakaeshi resemble the classic image of a yūrei: kimono-clad, long-haired, semi-translucent ghosts whose image fades away towards the feet. B : A fudakaeshi’s goal is to remove fuda–protective charms that ward against evil spirits. Fuda are usually made of strips of paper decorated with images or calligraphy, such as a sutra, or the names of a god or buddha. Yōkai are not able to enter buildings or cross boundaries protected by these talismans. If a fudagaeshi succeeds in removing a fuda, the charm is broken and yōkai are free to pass. I : As spirits themselves, fudagaeshi cannot touch fuda to remove them. They must convince humans to remove fuda for them. They do this with threats or bribes that tempt the weak hearts of the greedy and foolish. Not surprisingly, those who agree to help evil spirits in this way do not receive any promised reward; instead they meet with calamity. O : The name fudakaeshi appears in Kyōka hyakumonogatari, a collection of comical yōkai-themed poems from the late Edo period. However, the concept of spirits attempting to remove protection charms goes back much further than that. L : An example of a fudakaeshi appears in the famous ghost story Botan dōrō (“The Tale of the Peony Lantern”). A ghost which has fallen in love with a living man is unable to enter his house because of the protective charms placed on it. She begs the man to remove the charms so that she can enter and spend the night with him. Eventually, her pleading moves his heart, and he removes the talismans. The ghost enters his home and sleeps with the man, but in doing so she drains his life away and he dies. M T A ⽬競 : staring contest : dokuro no kai (“the phenomenon of skulls”) A : Mekurabe are great mounds of skulls and severed heads which hold staring contests. B : A Mekurabe pile begins when individual skulls roll around and bump into each other. Eventually they clump together and form into a massive skull-shaped mound. Then they find someone to stare at. I : Mekurabe are known for one thing: staring at people. If you win the staring contest, the skulls vanish without a trace. If you lose? Nobody knows, as this was never written down. O : Mekurabe appear in Heike monogatari (“The Tale of the Heike”). The name was invented much later, appearing in Toriyama Sekien’s Konjaku hyakki shūi (“Gleanings of One Hundred Demons from Past and Present”). L : Taira no Kiyomori, the young general who had recently conquered all of Japan, stepped out into his garden one morning to discover an uncountable number of skulls. They rolled about, glaring at him. The surprised Kiyomori called for his guards. But nobody heard him. As Kiyomori watched, the skulls gathered in the middle of the garden. They clumped together, rolling up on top of each other until they formed a single giant mass. The pile of skulls was shaped like one enormous skull nearly 45 meters tall. The mass of skulls glared at Kiyomori from its countless eye sockets. Kiyomori took a breath and steadied himself. He steeled his resolved and glared back at the skulls. Eventually, the massive skull crumbled apart. The individual skulls melted like snowflakes in the sun and vanished without a trace. G T H D 五徳猫 : trivet cat : fireplaces : carnivorous A : Gotoku neko are a kind of nekomata–large yōkai cats with two tails. They wear an upside-down trivet on their heads like hats. The tips of their twin tails burn like torches. B : Just as ordinary cats like warmth, gotoku neko hang around fireplaces. They use bamboo pipes to blow air on the fire and stoke the flames. O : Gotoku neko was invented by Toriyama Sekien in his book Hyakki tsurezure bukuro (“An Idle Bag of One Hundred Vessels”). Its name comes from the gotoku–or trivet–that this yōkai wears like a hat. A gotoku is an iron ring with three or four legs used to hold a tea kettle or pot in a fireplace. It heats vessels while keeping them out of the ashes. Gotoku have occult connections of their own: a famous curse known as the shrine visit at the hour of the ox requires wearing a gotoku upside-down on your head. Gotoku also refers to the five virtues of Confucianism: benevolence, honesty, knowledge, integrity, and propriety. It is somewhat odd for a yōkai to be associated with virtues, but Sekien makes a joke of it by referring to a story from Tsurezure gusa (“Essays in Idleness”). There was a nobleman named Shinano no Zenji Yukinaga, who was set to perform shichitoku no mai (“the dance of seven virtues”). However, as he danced before the court, he forgot two of the virtues. As a result, he jokingly became known around the court for his dance of five virtues (gotoku). Sekien connects this wordplay to the yōkai by explaining that gotoku neko are often forgetful. Cats are often associated with superstitions about house fires. For example, if you let a cat sleep near the fireplace, your house will burn down. It was said that the sparks from the fireplace would ignite the cat’s tail, and then the flaming cat would run around the house igniting everything it touched. Although Sekien does not mention it, the flames on gotoku neko’s tails might be a reference to this superstition. B T A H D びろ〜ん : none; onomatopoeic : nuribotoke : unknown : unknown A : Biron are elongated, white, ghostly looking yōkai with drooping features, protruding teeth, and long tails. They have soft, flabby bodies with gelatinous consistency reminiscent of konnyaku jelly. B : Biron enjoy scaring humans by caressing their heads or necks with their long tails. I : Biron are not particularly harmful yōkai. They can be easily chased away by throwing salt at them, which causes them to vanish. O : Biron’s origins are shrouded in mystery. Supposedly, they are the result of a magical mishap by a shapeshifting yōkai who tried to transform into the shape of a buddha by chanting, “Biro! Biro! Biro~n!” But the spell failed, resulting in biron’s strange appearance. The oldest written description of biron is a 1972 yōkai encyclopedia by Satō Arifumi. Along with its illustration and description, he notes that it is also called nuribotoke. During an interview late in his life, Satō claimed that biron and its magical spell were recorded in a Heian or Edo period picture scroll which was reproduced in an Edo period booklet containing copies of Toriyama Sekien and other artists’ yōkai illustrations. Unfortunately, Satō could not remember the name of the booklet or its whereabouts. He died with it still a mystery. Other yōkai researchers have never found the book he described. Additionally, the 〜 character in biron’s name was not used during the period in which it was said to have originated, adding even more mystery to Satō’s claim. With no surviving older sources, biron is considered to be a creation of Satō Arifumi. N T H D 納⼾婆 : storeroom hag : storerooms, closets : whatever they can find in the storeroom A : Nando babā are hags who haunt storerooms and closets in western Japan. They look like short, ugly, balding old women in ragged clothing. B : Nando babā make their homes in storerooms, sheds, and closets. The darker and dirtier the better. They are shy and jumpy, so they prefer storerooms which remain closed and are rarely opened. I : Nando babā are not violent or harmful. When someone opens the storeroom door they scurry away and hide. If the door is opened suddenly and they are taken by surprise, they leap out of the storeroom screaming and chase people around the house. If struck on the head with a broom, they become disoriented. They run away and hide under the floorboards. In some areas, nando babā are believed to steal newborn infants. However, this is due to confusion between nando babā and a much more dangerous mountain hag called yama uba. O : In ancient Japanese religion, there were different tutelary deities for every part of the house. As ancient traditions were replaced by modern ones many customs died, and old forgotten gods became yōkai. Nando babā were probably once a kind of house god or protector spirit which inhabited and watched over storerooms. F T H 袋狢 : bag badger : homes A : Fukuro mujina look like mujina (badgers; however, this word sometimes refers to tanuki as well). They dress in human clothes and wear make-up, resembling ancient noblewomen. They carry large sacks over their shoulders. O : The name fukuro mujina was coined by Toriyama Sekien and appears in Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. His illustration was based on older yōkai picture scrolls. Sekien’s description includes a pun based on the old proverb “to price a badger in a hole.” The idiom means it is difficult to estimate the value of something you don’t possess. It is like the English phrase “to count your chickens before they are hatched.” Mujina are known to be shapeshifting tricksters. However, fukuro mujina originally appear in a collection of tsukumogami, or artifact spirits. It is likely that they are actually haunted bags taking on the appearance of mujina, rather than mujina pretending to be humans. K T H 絹狸 : silk tanuki : homes A : Kinutanuki are pieces of silk cloth which sprout heads, feet, and tails resembling tanuki. They are a kind of tsukumogami, household objects which have come to life. O : Toriyama Sekien invented kinutanuki for his book Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. Their name is a play on words. Traditionally, when silk was made, it was taken to a river and beaten with a wooden board called a kinuta to soften it. Tanuki are said to enjoy beating their bellies like drums. The name kinutanuki is a portmanteau of the words kinuta and tanuki and evokes both the beating of silk and tanuki’s bellies. According to folklore, tanuki possess the ability to enlarge their scrotums to up to eight tatami mats in size and shape them into various objects. Sekien’s description references a famous type of Japanese silk from Hachijō Island. Written with different kanji, hachijō also means “eight tatami mats.” This wordplay doubles down on his association of silk with tanuki. Tanuki are famed for their ability to change into various objects, however because kinutanuki appear in a book of tsukumogami it is likely that they are not tanuki disguised as silk, but pieces of silk which have grown a soul and taken on a tanuki’s appearance. H T H 払⼦守 : fly-whisk guardian : temples A : Hossumori are animated hossu–fly-whisks used by Buddhist priests. After many years of being handled by a Zen master, they have become enlightened themselves. O : Hossu are religious tools originating in India. To a meditating monk, flies and biting insects can be distracting and troublesome. However, killing is a grave sin in Buddhism–even swatting a fly or a mosquito is forbidden. A hossu is used to gently brush away insects which land on the body instead of killing them. In addition to their practical use of keeping insects away, hossu are symbolic tools of warding which drive away evil spirits and other intrusions which distract from focusing on the Buddha. Hossumori appear in Toriyama Sekien’s Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. He references a famous Zen teaching in which a student asks Zen master Jōshū whether dogs have buddha nature. Sekien suggests that if even a dog has a buddha nature, then perhaps a hossu used for nine years by a Zen master might also realize its buddha nature. Nine years refers to the nine years that Daruma (aka Bodhidharma), the founder of Zen Buddhism, spent in meditation. M T H ⽊⿂達磨 : wooden fish gong Daruma : temples A : Mokugyo daruma are animated mokugyo–fish-shaped wooden gongs used in Buddhist temples. After years of service helping monks to focus on their meditations, these gongs have become conscious and achieved enlightenment. O : Mokugyo are used to keep the rhythm when chanting sutras. They also help keep monks from falling asleep during meditation. Because fish sleep with their eyes open, it was believed that fish did not sleep at all. Thus, the fish is a reminder to avoid falling asleep while meditating. Toriyama Sekien describes mokugyo daruma in Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. He says that a mokugyo might possibly gain a soul and take on the features of Daruma (aka Bodhidharma), the founder of Zen Buddhism, after nine years of being used by ascetic practitioners. Like a mokugyo, Daruma is a symbol of wakefulness. He is said to have meditated for nine years straight without sleeping. Due to their shared symbolism, Sekien combined these two figures of wakefulness into one yōkai. S T H 鈴彦姫 : bell princess : shrines A : Suzuhiko hime are possessed bells (kagura suzu) used in Shintō rituals. They look like young women wearing the robes of an ancient princess or shrine maiden. Suzuhiko hime are decked with bells and have a large bell for a head. B : Suzuhiko hime do not cause any harm. They dance about under their own power in ritualistic movements, just as when they were played by shrine maidens. O : Bells have been used since ancient times in Shintō rituals to calm human souls as well as repel evil spirits. Importantly, they attract the attention of gods and call forth their presence. Although not specifically stated, it is likely that as with other artifact spirits, suzuhiko hime are born from old tools that are no longer in service. They animate themselves in a desire to be useful again. Suzuhiko hime are a creation of Toriyama Sekien. They appear in his book Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. Everything about this yōkai, from the meaning of its name, to what Sekien intended for it, can only be inferred from his brief description of it. Sekien’s description refers to a famous scene from Japanese mythology. Amaterasu, the sun goddess, had a violent quarrel with her brother Suzano’o, the god of storms. Afterwards she hid herself from the other gods in a cave. Without the sun, the world became cold and dark. The gods gathered outside of the cave and begged Amaterasu to come out, but she refused. Ame no Uzume, the goddess of dawn and revelry, came up with a plan. She stood upon an upturned tub and performed a wild, erotic dance, stripping off her clothes and baring herself to the other gods. Their loud, uproarious cheers could be heard by Amaterasu deep inside the cave. Eventually Amaterasu’s curiosity got the better of her. She left the cave to see what the commotion was about. The other gods quickly blocked the cave entrance so she could not go back inside, and light was returned to the heavens and the earth. Ame no Uzume’s performance is said to be the origin of kagura, the sacred music and dance of Shintō rituals. Kagura, in turn, is the origin of this yōkai. O T H 笈の化け物 : backpack monster : homes and temples where pilgrims might stay A : Oi no bakemono are the spirits of wooden backpacks known as oi. An oi which has been used for a long time may transform into this bird-like yōkai. They sprout heads with long, black hair, and have three-toed avian feet. B : Oi no bakemono carry broken sword blades in their mouths, resembling a bird’s pointed beak. They breathe fire. O : Oi are special backpacks carried on long journeys by itinerant Buddhist monks, pilgrims, and yamabushi (mountain ascetics who practice Shugendō). They contain Buddhist religious implements, clothing, tableware, and other necessities monks will need on their journeys. Oi no bakemono are found in the book Ehon musha bikō. One appears in the bedroom of Ashikaga Tadayoshi–a general and government administrator during the 14th century. Tadayoshi helped his brother Tadauji establish the Ashikaga shogunate, which ruled Japan for over 200 years. U T 雲外鏡 : mirror beyond the clouds A : Ungaikyō are haunted mirrors which show demons and monsters reflected in their surface. B : The spirits which haunts these mirrors, as well as the countless spirits which have been reflected in them over the years, can manipulate the reflections and cause them to appear as anything they like. People who gaze into an ungaikyō might see themselves looking back, transformed and monstrous. I : Ungaikyō can be used by humans to trap spirits. On the 15th night of the 8th month in the old lunar calendar, pour water into a crystal dish and reflect the light of the full moon. (In olden days this was a popular way of admiring the reflection of the night sky.) If that water is then used to paint the image of a yōkai onto a mirror, that spirit will inhabit the mirror. O : Ungaikyō appears in Toriyama Sekien’s book of tsukumogami, Hyakki tsurezure bukuro. Sekien based this yōkai on a mirror from an old Chinese myth. Called Shōmakyō (“demon revealing mirror”), this mirror had the ability to expose the true forms of demons masquerading as humans. King Zhou of the Shang dynasty used Shōmakyō to reveal that his beloved consort Daji was a wicked nine-tailed kitsune intent on ruining his kingdom. Her true form revealed, Daji fled the country. This set into action a chain of events that would see Daiji eventually wind up in Japan, where she was known as Tamamo no Mae. Shōmakyō was used time and time again to reveal the true nature of disguised spirits. Sekien postulated that such a mirror might pick up a little of the strangeness of each yōkai and demon it reflected, eventually becoming one itself. Perhaps the countless spirits reflected over the years slowly gained the ability to manipulate its reflections. More recently, ungaikyō has been described simply as a mirror which has transformed into a conscious being. Upon reaching one hundred years of age, the mirror develops a soul and is transformed into a yōkai–a common theme among tsukumogami. Ungaikyō has also been portrayed as one of the many transformations performed by tanuki. By sucking in air and inflating their bellies, a tanuki can display a picture on its bare belly similar to a television screen. This portrayal is not rooted in folklore; it comes from Daiei Films’ 1968-69 yōkai movies. Nonetheless, it has caught on and remains a popular version of ungaikyō. N T A H 鳴釜 : ringing kettle, crying kettle : narikama, kamanari : kitchens A : Narigama are spirits which inhabit iron kettles used to cook rice in old Japanese kitchens. They have long arms and legs, with bodies covered in dark hair as if wearing animal pelts. Flames lick the sides of the kettle which either serves as their head, or which they wear like a helmet. B : A narigama’s most amazing talent is the ability to predict the future. When water is boiled inside of a narigama, it rings out or even cries like an animal. I : An onmyōji or a priest can divine good and bad fortunes based on the sounds the narigama makes as its contents are boiled. Depending on the sound that it emits, it is possible to know whether the weather will be rainy or fair. O : Although they appear without a name or description, narigama are shown cavorting with other tsukumogami in some of the oldest yōkai picture scrolls. Toriyama Sekien later included narigama in Hyakki tsurezure bukuro and gave a brief history. According to Sekien, narigama were first described in Hakutaku zu (“The Book of the Hakutaku”), an ancient bestiary of all supernatural creatures in the world. Hakutaku zu states the narigama’s ability to “ring” is connected to an ancient oni named Renjo. The Edo period book Kansō kidan also describes Renjo as haunting kettles. When a narigama rings, if you stand three shaku (about ninety centimeters) away from it and loudly say the name “Renjo,” fires will descend into the earth, beneath the house. The haunting will end, and the household will be blessed with good fortune. At Kibitsu Shrine in Okayama Prefecture, priests still practice a folk ritual called narukama which involves boiling a kettle and examining the sounds it emits to predict good and bad fortunes. According to the Okayama tradition, the ritual’s powers derive not from Renjo, but from an ancient oni named Ura who long ago terrorized the region. Eventually Ura was slain. Even in death his head continued to cry out. Its flesh was eaten away to the bone by dogs, yet still cries emitted from its empty skull. Ura’s head was buried beneath the shrine’s kitchen to silence it. But it could still be heard groaning beneath the kettles. Finally, a priestess named Aso hime offered a sacrifice of food to Ura’s restless spirit. This quieted him at last. Since then, Ura’s spirit speaks from the crying kettle to foretell good and bad fortunes to the Kibitsu Shrine priests. Toriyama Sekien may have based his description on the narukama ritual, altering the legend and connecting it to ancient China in order to make it seem more authentic. N T H D 鷄の僧 : chicken monk : temples and monk’s hermitages : chickens A : Niwatori no sō are monks who have transformed into human-chicken hybrids. They have large, feathery tails and crow like roosters. Sometimes a chicken’s head protrudes from their mouths. B : Niwatori no sō crow and act like chickens, exposing monks who kill and eat animals. They are created by the vengeful spirits of chickens who were eaten. The chickens’ grudge manifest by transforming monks into monsters, providing evidence of sins that may have otherwise gone unpunished–in this case, the sins of stealing, killing, and eating animals. O : Sinful clergy receiving supernatural punishment is a common theme among yōkai folklore. Buddhist monks are expected to live austere lives. They wake before dawn to practice chanting. They spend their mornings copying scripture and meditating. They spend their afternoons begging for alms in the villages. One of the most important rules that monks live by is to never take a life. As such, they are forbidden from eating meat. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that every monk is a strict vegetarian. But a monk who kills and eats chickens can expect divine retribution. L : Niwatori no sō is found in Okada Gyokuzan’s 18th century book of illustrated yōkai tales Ehon yōkai kidan. A monk stole a chicken from his neighbor’s yard, killed it, and ate it. The neighbor noticed that one of his chickens was missing. When he questioned the monk, the monk grew outraged. He pointed at his shaved head and his monk’s robes. He chastised the neighbor that no monk would ever stoop to something like stealing, let alone killing and eating a chicken. He proceeded to lecture about compassion and charity, but as he spoke a loud “cock-a-doodle-doo!” came from his throat. An instant later, a chicken’s head erupted from his mouth and a feathery tail sprouted from his back. The monk transformed into a chicken monster, exposing his crime. S T A H D 鼈の幽霊 : softshell turtle ghost : suppon no bakemono : places where softshell turtles are eaten : none; thrives solely on vengeance A : Suppon no yūrei are vengeful ghosts of suppon– softshell turtles (Pelodiscus sinensis). They appear as giant ghosts with long, legless bodies, and prominent, pointed lips like softshell turtles. B : Like kitsune, tanuki, and other animals, suppon were believed to have powerful magical abilities. In addition, suppon were known for their tenacity. If one bit you it would never let go. Accordingly, the ghosts of suppon were believed to be particularly tenacious; their curses especially hard to break. I : Suppon no yūrei haunt humans involved in the catching, selling, and eating of softshell turtles. Their victims are usually people who have gorged on suppon meat, and the owners of bars and restaurants where suppon are served. There are several ways in which suppon no yūrei haunt their victims. Often, they manifest as another yōkai–a gigantic monk called a taka nyūdō. In this form they terrorize offending human. Another common method is to possess victims and cause them to take on the facial and body features of softshelled turtles. O : Suppon have been a delicacy in the far east for thousands of years. In addition to being used for food, they are believed to have restorative and invigorative powers. They are used in traditional Chinese remedies as well as modern energy drinks, vitamins, and other fad health supplements. L : One particularly tragic story tells of a man who made his living by catching and selling suppon. The deep and long-last grudge of all the suppon he caught manifested as a huge taka nyūdō. It stood over thirty meters tall and haunted him night after night. On top of that, his own baby was born disfigured with features resembling a softshelled turtle. The child had hair longer than his body, webbed fingers and toes, and large, round eyes. His lips were long and pointed, and because of the shape of his mouth he could not eat regular food. His parents had to feed him worms. S T A D C 塩の⻑次郎 : Salty Chōjirō : Shio no Chōji, umatsuki : horses A : Shio no Chōjirō was a wealthy man from Oshio no Ura, Kaga Province (present-day Ishikawa Prefecture). He is known for his love of horse flesh and the curse that this sinful pleasure brought upon him. His curse is also known as umatsuki–possession by a horse spirit. O : Shio no Chōjirō’s story is an old one with many variations. It appears in the Edo period story collection Ehon hyakumonogatari, however it was a well-known tale before then, with variations all over Japan. It may have been inspired in part by famous performance magician who lived in the late 17th century named Shioya Chōjirō. Shioya Chōjirō could perform sword swallowing and other tricks but was best known for his donbajutsu (“horse swallowing technique”) in which he would swallow a live horse before an audience. Illustrations of his performances appear to have been used as the basis for his illustration in Ehon hyakumonogatari. L : Long ago in lived a very wealthy man named Chōjirō who was quite fond of eating meat–a taboo practice in feudal Japan. His household kept over 300 horses. Every time one of his horses died, he pickled its meat in salt or miso to eat at his leisure. Thanks to this, he always had plenty of sinful meat to enjoy. As the years passed, Chōjirō’s horses dwindled in number. Consequently, so did his stock of pickled horse meat. One day his supply ran out altogether. He selected an old horse that was no longer capable of working, slaughtered it, and ate it. That was the moment his life changed. Chōjirō dreamed that the old horse appeared in front of him and snapped at his throat. The next evening, at the very minute that Chōjirō slaughtered the horse, its ghost appeared. It forced itself down his throat and into his stomach, where it began to violently thrash about. Every day after that, the haunting repeated. Chōjirō’s suffering was unbearable. He developed a high fever and hallucinated. He screamed and babbled, confessing his life’s sins in painful delirium to everyone he saw. Doctors examined him and priests prayed for him, but nothing helped. He descended into madness. Chōjirō’s condition continued to deteriorate. One hundred days after his haunting began, he succumbed to the horse’s curse. When his body was found, it was said has back was bent like an old horse who had spent a lifetime carrying heavy loads. N T D 寝肥 : sleep fattening : insatiable A : Nebutori is a supernatural illness that affects women who sleep too soon after meals. B : Women who eat and sleep right afterwards massively expand during the night. Their appetites grow, causing them to eat more and more, and consequently expand more and more. Eventually they become too big to even leave their rooms. In addition, they snore with enough force to shake a wagon on the street. Women with nebutori lose their sex appeal and develop loud, domineering personalities. If a home has ten futons, a woman with nebutori will take up seven of them and leave only three for her husband. O : Nebutori was a warning to women to maintain thin figures, gentle personalities, and to avoid oversleeping. It satirizes the stereotype of women who let themselves go once they capture a husband. A common Japanese superstition is that lying down after eating will turn you into a cow; nebutori is a twist on that concept. Nebutori is similar to other yōkai curses which mainly afflict women. It is described as more of a problem for the husband than for the wife, just as futakuchi onna is a punishment inflicted on miserly old men who are stingy with food, and rokuro kubi affects the daughters or wives of men who have committed terrible crimes. Even though these curses aflict women, they are presented as punishments for their husbands. Nebutori is sometimes blamed on tanuki or kitsune. Both animals can possess humans and cause them to do strange things. Tanuki in particular like to give their victims huge appetites. A T ⾜洗邸 : foot washing manor A : Ashiarai yashiki is a house in which a giant, dirty, hairy foot appeared and demanded to be washed. This bizarre Edo period phenomenon took place in Honjo (present-day Sumida Ward, Tōkyō), and is one of the Seven Wonders of Honjo. L :One night, at the manor of the hatamoto Aji no Kyūnosuke, a loud, booming voice was heard heard. It echoed like thunder: “WAAASH MYYY FOOOOOOT!” Suddenly there was a splintering crack, and the ceiling tore open. An enormous foot descended into the manor. It was covered in thick, bristly hair. It was filthy. The terrified servants scrambled to gather buckets, water, and rags. They washed the foot until it was thoroughly clean. Afterwards, the giant foot rose up through the roof and disappeared. For several nights, the same thing occurred. A booming voice demanded that its foot be washed. Then a giant foot crashed through the roof. Dutiful servants washed it clean. A few nights of this were all that Aji no Kyūnosuke could take. He ordered his servants not to wash the feet anymore. That night, a foot again crashed through the ceiling and demanded to be washed. The servants ignored it. Then the foot thrashed around violently, tearing up the manor and destroy its roof. Kyūnosuke complained to his friends about the nightly apparition and the destruction it was causing. One of them was so curious he offered to swap mansions with Kyūnosuke so he could see it for himself. Kyūnosuke happily agreed. However, after his friend moved in the giant foot never appeared again. There’s no conclusion as to what caused the strange occurrence. It has been blamed on a mischievous tanuki, for they have magical powers, and are notorious tricksters. On the other hand, “to wash your feet” is a Japanese idiom for rehabilitating a criminal. Someone whose feet have been washed can be said to have paid his debt to society. One interpretation of this story is that Aji no Kyūnosuke had committed some kind of crime, which caused this yōkai to appear and demand that he “wash his feet.” Y T A H 疫病神 : pestilence spirit : ekibyō gami, yakushin, ekiki, gyōyakujin : human-inhabited areas A : Yakubyō gami are evil spirits which spread infectious diseases and misfortune. They are invisible to the human eye but often depicted in art as grotesque monsters resembling oni. On rare occasions when yakubyō gami appear before humans, they take the form of elderly priests or old hags. B : Yakubyō gami travel from person to person and place to place, spreading sickness and misfortune wherever they go. They haunt a person or a household for a short time. Then, when their victims have become infected, they move on to their next target. I : There are many ways to protect against yakubyō gami. Ropes called shimenawa are strung around trees at the borders of villages to prevent evil spirits from entering. During the Edo period, images of powerful protective spirits–such as amabie, baku, hakutaku, hōnengame, jinja hime, kotobuki, Shōki, and so on– were hung in houses to frighten yakubyō gami away. Buddhist and Shinto talismans are still used today to ward off such spirits. People also try to appease yakubyō gami by honoring them as gods. Since ancient times, offerings of food have been regularly given by priests and government officials to prevent epidemics. Many of today’s popular festivals and celebrations have their roots in rituals designed to appease yakubyō gami. O : Yakubyō gami are among the most feared yōkai. They frequently appear in folklore and art of the second half of the 19th century, when several epidemics struck Japan. But belief that sickness and misfortune are caused by invisible spirits has always been a major part of Japanese folklore. Before we understood about infectious germs, people had no idea how diseases spread. The way sickness moves from person to person and house to house seemed very much like an invisible spirit visiting people and cursing them. Many yōkai fit into this category: amazake babā, bake kujira, kaze no kami, keukegen, korōri, momonjii, and yonaki babā are all examples of yakubyō gami. L : In 1820 in Edo, a samurai managed to capture a yakubyō gami as it entered his house. In exchange for its freedom, the spirit promised to spare everyone in the samurai’s family from sickness and misfortune. It gave him a written contract agreeing to never enter his house again. Afterwards, the samurai’s story and the entire contents of the contract were published in newspapers with instructions to keep it as a talisman. Before long, houses all over Edo each had their own printed copy of the yakubyō gami’s contract. M 箕借り婆 T : winnowing basket borrowing hag A : mikawari baba, mekari baba (“eye borrowing hag”) H : villages in Eastern Japan D : whatever scraps they can steal A : Mikari baba are greedy hags from the Kantō Region who look like old women missing one eye. They wear old straw hats and coats and carry a flaming torch in their mouths. B : Mikari baba appear in the winter and creep into villages. They go from house to house begging to borrow raincoats, winnowing baskets, or even just a few grains of rice. They even try to “borrow” an eye from a person’s head. Their greed compels them to scour gardens for every last grain of rice. Mikari baba search with their faces so close to the ground that the torches they carry in their mouths ignite fires. Mikari baba appear on fixed dates during the year. These dates vary from tradition to tradition, but usually fall on the eighth day of the second or twelfth month of the lunisolar calendar. These dates are rooted in ancient religious practices surrounding new year rituals and are referred to as kotoyōka (“eighth day events”). Mikari baba keep away from objects with multiple holes in them. This includes things like bamboo sieves and woven cages. The holes resemble eyes. Jealous, one-eyed yōkai like mikari baba detest or even fear such objects. Mikari baba often appear together with a smaller one-eyed yōkai called hitotsume kozō. Together they travel from house to house, writing the names of families in a ledger which they present to the gods of pestilence a few weeks later. The gods use their report to mete out sickness and misfortune to people as they see fit. I : In Chiba, Kanagawa, Tōkyō, and other places where mikari baba appear, villagers stay at home and remain quiet on set dates. Loud voices, lighting lamps, hairdressing, and bathing are avoided. Leaving the house after dark and entering the mountains are forbidden. Measures are taken to discourage mikari baba from approaching the house. Fallen grains of rice on the floor and in the gardens are gathered and made into a dango which is placed in the doorway to show that there is not even one grain of rice left to pick up. Bamboo baskets, sieves, and other woven objects with many “eyes” in them are hung outside of houses or placed on tall bamboo poles throughout villages to scare them away. O : The kanji in mikari baba’s name literally mean “winnowing basket borrowing hag.” This is likely a folk etymology that was invented after she was named. The word mikari has an older meaning, referring to a period of fasting and purification before ancient religious ceremonies. It was believed that yōkai were more likely to appear before religious festivals like New Year’s. People stayed home and refrained from work and normal activities prior to such events. This period of quiet isolation was called mikari or mikawari (“changing oneself”), referring to the interruption of regular daily life in preparation for religious festivities. Because it was forbidden for people to be outside during the mikari period, any person coming to your house was sure to be a yōkai. Mikari baba was the name given to one of these yōkai, and the kanji for her name were added later to reflect her behavior. K T H ⾵の神 : wind spirit : rides on the wind A : Kaze no kami are invisible evil spirits who cause sickness. They are usually portrayed in paintings as old, sickly, apelike demons wearing ragged loincloths. B : Kaze no kami travel on the wind, riding it from town to town in order to spread disease. They inflict suffering both through their control of the wind as well as through the illnesses they spread. I : Kaze no kami slip into homes through small cracks and crevices, sensing the temperature differences between the warmer inside air and colder outside air. When they encounter people, they exhale clouds of humid, yellow breath. Any human breathing this toxic air falls sick. In addition to spreading disease with their breath, kaze no kami control the flow of the wind itself. Workers whose livelihoods were greatly influenced by the wind, such as farmers and fishers, feared their capricious nature. In many places kaze no kami are enshrined as gods to avoid provoking their wrath. O : The yellow breath which kaze no kami exhale may be a representation of the yellow dust which falls heavily upon Japan in the early spring. Wind erosion of northern China’s Huangtu Plateau stirs up silt into the atmosphere. The silt travels eastward and falls upon Japan and other countries in the form of yellow dust. It can cause respiratory issues and even darken the sky on particularly heavy days. The combination of early spring’s temperature fluctuations, humid winds, and yellow dust often causes people to feel sick. In old times this was believed to be the work of malicious spirits. Advancements in medicine eventually ended the belief in wind spirits as carriers of disease, but the superstition is preserved in the Japanese language. The word for the common cold is kaze, which translates to “evil wind.” Similarly, the phrase kaze ni au–“to encounter the wind”–means to suddenly fall sick or to meet with misfortune. T T H D 恙⾍ : illness bug : deep in the mountains : human blood A : Tsutsugamushi are large, insect-like yōkai which live deep in the mountains along the Sea of Japan. Tsutsugamushi larvae are orange. Adults are red, with massive mandibles, long antennae, and a pincer-like tail. They feed on the blood and the life force of humans living in rural areas. B : Tsutsugamushi spend most of their lives hidden away from human eyes, but they emerge at night and creep into homes to drain the blood from villagers. They cause all kinds of illnesses in the people they feed upon, from fever, headache, muscle pain, coughing, and gastrointestinal symptoms, to hemorrhaging and blood clotting. They often kill their hosts. I : Doctors investigating the bodies of people suffering from or killed by these yōkai found that they all had one common symptom: dark lesions all over their bodies. Because no culprit was ever found, they concluded that a species of invisible yōkai was sucking people’s blood while they slept. The sickness caused by these yōkai was named tsutsugamushi disease. Because it was caused by a supernatural creature, it had to be treated by supernatural forces, such as the magic of an onmyōji. O : The sickness attributed to these yōkai is now known to be scrub typhus. It is caused by parasites transmitted to humans by harvest mites. It occurs all over of East Asia and the Pacific islands. It was a problem for troops on both sides of the Pacific War. If recognized early enough the disease can be treated. Without treatment it is often fatal. There are about one hundred different species of mites which transmit scrub typhus in Japan. In Japanese it is still called tsutsugamushi disease, and these mites are collectively called tsutsugamushi. The parasite which causes the illness is known as Orientia tsutsugamushi–named after the yōkai. K T H A 腰抜の⾍ : back dislocating bug : the lower back : Koshinuke no mushi look like dragonflies. B : Koshinuke no mushi appear suddenly and fly inside bodies, taking up residence in the lower back. I : After successfully entering their host, koshinuke no mushi entwine their long tails around the spine. When they squeeze the vertebrae, they cause strains, slipped disks, and other problems. When they strike the spine with their spiked tails, the host is overcome with acute pain. Their legs buckle and collapse. Their chest becomes tight and breathing becomes difficult. They break out in cold sweats. As this yōkai’s saliva spreads throughout the body, it causes heartburn, choking, and vomiting. Koshinuke no mushi infections can be treated by ingesting herbal remedies such as mokkō (Saussurea costus) and kanzō (Glycyrrhiza uralensis). K T H 腰痛の⾍ : lower back pain worm : the kidneys A : Koshiita no mushi are infectious yōkai worms with black heads, white bodies, and long, pointed beaks like birds. B back. : Koshiita no mushi live in the kidneys and affect the lower I : Koshiita no mushi use their beaks to peck at their host’s muscles from inside the body, causing all sorts of pain throughout the lower back. The lower back begins to feel heavy and sore, and in severe cases movement becomes impossible. Treatment is accomplished using the dried roots of the thistle mokkō (Saussurea costus). S T H ⼨⽩⾍ : segmented white worm, tapeworm : the abdomen A : Subakuchū are long worms with dragon-like faces and forked tails. B : Subakuchū don’t have a fixed home; they travel back and forth between the abdomen and the scrotum. Ordinarily they spend their time stretching left and right around the belly, wriggling up and down below the diaphragm. However, when their host’s body becomes cool, they slither into the scrotum and coil up, remaining motionless. I : People infected with subakuchū suffer from acute bouts of abdominal pain once or twice a year. The longer the subakuchū get, the more dangerous they become. By the time they reach 15 meters, the host is sure to die. They can be treated with acupuncture, although recovery is difficult. The trick for treating them is a secret which is only passed down orally. O : The su in subakū comes from one sun and refers to the segments of tapeworms. A sun is old Japanese unit of measurement equal to about 30.3 millimeters. K T H 噛み⼨⽩ : biting tapeworm : the abdomen A : Kamisubaku are long white worms that live just behind the liver. Their long bodies are segmented, and each segment has a tiny, biting mouth. B : As kamisubaku slither around their host’s insides, their many mouths snap and chew at the internal organs. This causes intense abdominal pain. I : Medicine cannot treat kamisubaku, but there is a magical curse that can kill it. Finely chop some hairs from the tail of a dapple-grey horse and mix it with buckwheat flour. Add sake of the finest grade, and knead the mixture into dough. The hairs of what was once a beautiful horse tail carry with them a residual resentment of being chopped up. When the host eats the dough, the bits that the kamisubaku ingest transfer that resentment into the tapeworms. Their long white bodies are then torn apart from the inside out. N T H 鳴き⼨⽩ : crying tapeworm : the abdomen A : Nakisubaku are long white worms with heads at both ends of their bodies. B : If you squeeze the belly of an infected person, the worms let out an audible cry. I : The only symptom of this infection is that the patient’s stomach growls. They are easily cleared out by ingesting nira (garlic chives, Allium tuberosum) and binrōshi (seeds of the areca palm, Areca catechu). I T H 陰の⻲積 : yin turtle shaku (a type of infection) : the abdomen A : In no kameshaku resemble turtles with grey heads and shells, and black arms and tails. Several white, snake-like worms coil around their bodies. B : In no kameshaku kill their hosts. Afterwards, they remain inside of the body as it decomposes. Finally, they emerge from the bellies the putrid corpse. I : In no kameshaku can treated by ingesting medicine made from kochia (Bassia scoparia). It is a strong herb with diuretic properties. If this herb is mixed with regular meals and ingested, the in no kameshaku will be exterminated. O : Shaku is one of a few categories that medieval doctors divided infectious spirits into. It was believed that different types of energies would accumulate as shaku in the organs until they became a large mass, which would then cause various symptoms to occur. Y T H 陽の⻲積 : yang turtle shaku (a type of infection) : the stomach A : Yō no kameshaku resemble turtles with speckled red shells with a circular pattern on the top. They have a blue umbrellalike growth on their heads which protects them against any medicines that their host might ingest. B : Yō no kameshaku feed upon cooked rice that their host eats. The host stays thin no matter how much they eat. I : To extermine yō no kameshaku, there is no treatment more effective than eating the peas of the pongam oiltree (Millettia pinnata). The pongam tree’s effectiveness is not due to any medicinal properties, but to something more like a curse. To be eaten, the peas of the pongam tree must be removed from their shells. The pea then carries the residual memory of being removed. Upon eating a pea, a kameshaku absorbs that memory. Because their blue umbrella-like growth resembles the shell of a pongam tree’s pea, the kameshaku is overcome with the desire to remove its umbrella. Once this happens, the kameshaku loses its resistance to medicine. The host can then be cured by ordinary medicine. K T H 気絶の肝⾍ : fainting liver worm : the liver A : Kizetsu no kanmushi are worm-like parasites with big round eyes, and long blue bodies covered in black speckles. B : Kizetsu no kanmushi infect in the liver. I : People infected with kizetsu no kanmushi experience a string of symptoms. First, they lose their hair, which the worm feeds on. Then, they experience tunnel vision. Moments later, they suffer shortness of breath. Finally, they collapse as if dead. This infection can be cured with the herb gokō (Origanum vulgare). T T H 頓死の肝⾍ : sudden death liver worm : the liver A : Tonshi no kanmushi have yellow bodies covered in black speckles. They have red mouths, and red tongues. The tops of their heads are black. Their tails are tipped with a white string-like appendage. B : Tonshi no kanmushi infect the liver. I : When a tonshi no kanmushi bites down on the liver, its host will immediately die. Mokkō (Saussurea costus) is an effective cure for this infection. K T H 肝の聚 : liver colony : the liver A : Kan no ju are long worms with white, snake-like bodies. The tips of their tails and ears are red. B : Kan no ju infect the liver as a huge colony of worms. I : When kan no ju mature, they crawl higher and higher up the body, chewing their way to the liver and into the torso. They elongate their bodies and straighten out, then they wriggle violently. This causes stiffness throughout the host’s body, followed by violent tremors which cannot be stopped. There are ways to treat this infection with acupuncture, but these secrets are only passed down orally. Treatment becomes more difficult after the kan no ju have reached maturity. S T A H ⼼積 : heart shaku (a type of infection) : bukuryō : the heart A : Shinshaku look like a red hear with black head and limbs, and a dotted belly. B : Shinshaku infect the torso between the belly button and the heart, right behind the solar plexus. I : People infected by shinshaku develop a fondness for burnt smells and bitter flavors. They smile and laugh thoughtlessly. They often have flushed cheeks. Their force of will and emotional strength become very weak. Chinese medicine holds that the consciousness exists in the chest, around the solar plexus–right where the shinshaku is found. Treatment is possible using secret acupuncture techniques passed down orally. Early treatment is important; after shinshaku reach maturity they become much more difficult to treat. K T A H 肝積 : liver shaku (a type of infection) : hiki : the liver A : Kanshaku roughly resemble a breast. Their heads look like nipples, and their sack-like bodies resembles breast tissue. They have two long moustache-like growths sprouting from their heads. B : Kanshaku live in the liver; however, they are born in the left side of the chest. They develop in the area of the pectoral muscles and fiercely headbutt their host’s organs as they crawl around inside the body. I : Symptoms of kanshaku infection include anger, irritability, and a short temper. The host’s face grows pale and sickly. They develop a craving for sour, acidic foods, and a revulsion towards oily foods. Treatment is accomplished by alternating acupuncture techniques. First, the left side of the torso is treated. After that, the spine around the 9th thoracic vertebra is treated. When the patient’s energy is low, the shaku’s energy will also be low. A slow treatment is performed. The body is stabbed very gently with the needle. The needle is left in place for some time, after which it is quickly removed. The puncture wound is massaged deeply. When the patient’s energy is high, the shaku’s energy is high. In this case, the body is stabbed quickly with the needle, and then the needle is violently wiggled about. After that, the needle is slowly removed. The puncture area is not massaged. H T A H 疱瘡神 : smallpox god : hōsōshin, imomyōjin, and other regional names : areas infected with smallpox A : Hōsōgami are yakubyō gami responsible for smallpox. They appear in many forms but are often depicted as small demons. B : Hōsōgami travel from town to town, infecting communities with smallpox. They have fearsome tempers reflected in the ferocity and virulence of smallpox. They are afraid of dogs, and hate the color red. This is because red symbolizes good health. A red rash was a sign of recovery from smallpox. I : In infected households, families erected smallpox shrines and begged the hōsōgami to spare their loved ones. Although hōsōgami were feared and considered evil, it was believed that they could be appeased with rituals and offerings. Red woodblock prints called akae were hung in houses to scare them off. Various objects, such as red-papered priest staves and red clothing, were believed to have protective powers. Other popular talismans were shaped like dolls, dogs, owls, sea breams, cows, and the redhaired yōkai shōjō. Images of Daruma, Shōki, and Kintarō were also popular charms. Some gods were more effective against smallpox than others. Shrines to the warrior Minamoto no Tametomo were thought to keep hōsōgami away. When Minamoto no Tametomo fled to Hachijō Island during the Hōgen Rebellion, smallpox ravaged every part of the country except for Hachijō Island. It was believed he drove the sickness from the islands. The Shintō god of healing Sukunabikona was also a popular figure to worship. Smallpox affected entire communities. Large rituals called hōsōgami okuri (“sending off the hōsōgami”) developed in response to outbreaks. People played drums, flutes, and bells, and sang, danced, and paraded around the streets to send away evil spirits. Shrines and stone pagodas were erected at the outskirts of villages to keep hōsōgami from entering. In some areas, it was thought hōsōgami were not the cause of smallpox, but saviors. In these cases, smallpox was a physical manifestation of evil inside the human body. The infected prayed to hōsōgami for protection and salvation. Survivors offered thanks to hōsōgami for saving them. O : Smallpox is believed to have made its first appearance in Japan in the Nara period, a time of great exchange with continental Asia. The first recorded epidemic in Japan crossed from the Korean peninsula to Japan in 735 CE. It is described in the Heian period history record Shoku nihongi. Japan’s earliest outbreaks started in Dazaifu, an important center of politics and international exchange. This made an ideal port of entry for smallpox. Dazaifu is also famous as the home of the exiled scholar Sugawara no Michizane. After Michizane’s death, an outbreak of smallpox and the deaths of several of his rivals, including the emperor, were blamed on his restless spirit. It was believed Michizane had become a tatarigami–a curse-spreading god. His curse only ended after his stripped titles were restored and he was enshrined as the kami Tenjin. L : An eyewitness account of a hōsōgami was reported in a Meiji period newspaper. A rickshaw reported that he gave a ride to a young girl about 14 or 15 from Midorichō to Asakusa. Midway through the ride it began to grow dark, so he pulled over to light a lantern. However, when he stopped, the girl had vanished from the back of his rickshaw. In her place was a barrel lid with a red staff mounted to it: a symbol of a hōsōgami. The young girl must have been a hōsōgami using a rickshaw to find her next victim. K T A H D ⻁狼狸 : cholera; literally “tiger wolf tanuki” : kororijū (“cholera beast”) : homes infected with cholera : corpses of cholera victims A : Korōri are chimeras made of parts of the three animals in their name: tiger, wolf, and tanuki. They have the body of a tanuki, the stripes of a tiger, and the ferocious maw of a wolf. B : Korōri were said to be responsible for spreading cholera in Japan in the late 19th century. I : Korōri take up residence in homes and infect families with cholera. They are occasionally seen fleeing homes after residents recovered. They can also be seen feeding on corpses of those who succumbed to the sickness. O : Many cholera outbreaks struck Japan during the late Edo and early Meiji periods. These epidemics killed hundreds of thousands of people and created an atmosphere of fear and unease. Because microbes responsible for cholera are invisible to the naked eye, people believed cholera was the work of evil spirits. It was sometimes blamed on possession by a type of kitsune called an osaki. Later, it was thought to be the work of a brand new yōkai which had never been seen before. The word cholera was imported in Japanese as korori. Various combinations of characters were used to write the sounds. One used the kanji for tiger (⻁ ko), wolf (狼 rō), and tanuki (狸 ri). This spelling elicited a new creature which combined the characteristics of those three animals. An 1877 newspaper article printed an illustration and description of the new beast, containing a disclaimer that korōri was not a real animal, but an imaginary representation of how fearsome the disease was. In other words, the yōkai korōri’s real identity is the fear of cholera, not than the disease itself. L : There were several korōri sightings during an 1862 cholera outbreak in Edo. A samurai recovering from the disease witnessed a strange beast resembling a weasel lurking about his home. He grabbed a piece of firewood and beat it to death. He roasted the animal and ate it. Later, in the same village, other families with cholera infections noticed a similar animal lurking around their homes. More and more sightings of these strange beasts were subsequently reported. They were even spotted emerging from the bodies of dead cholera victims. H T H はしか童⼦ : measles boy : areas infected with measles A : Hashika dōji is the personification of measles in Japanese prints. He is a large, ugly, muscular boy with red pox all over his body. O : Measles has been endemic to Japan since ancient times. A rite of passage that everyone went through at some point in their life, thirteen major epidemics were recorded during the Edo period alone. Various folk remedies were devised for measles over the centuries. Many of them resemble traditions of other infectious diseases like smallpox. Small shrines to the gods of disease were built to appease them so they would spare the lives of the infected. Images believed to have special warding powers were hung as talismans in homes where measles appeared. Images used to combat the spread of measles were called hashikae (“measles pictures”). They became popular towards the end of the Edo period when new ideas about medicine were beginning to arrive in Japan. They were produced in large quantities and distributed around infected areas during outbreaks. Hashikae served a dual purpose; not only were the images used for good luck and to keep the evil spirits who cause measles at bay, but they were also informative. They contained detailed instructions on disease prevention, including lists of things to abstain from and medicinal foods to eat. Important things to avoid during infection included sex, fish and shellfish, poultry, alcohol, oily foods, and pickled vegetables. Foods that were supposed to be helpful against measles included azuki beans, winter melon, lily, kanpyō, miso, sweet potato, black soybeans, barley, and zenmai. Some hashikae even described the history of measles in Japan and techniques to treat the infected. Hashika dōji was a popular figure in hashikae. He was often depicted being captured, tied up, and beaten by small, anthropomorphic figures representing the industries which suffered most during outbreaks. People with kegs for heads represent sake breweries, while tub-headed people represent bathhouses. The entertainment industries were represented by prostitutes or people with pleasure boats for heads. These figures all teamed up to defeat the gigantic Hashika dōji and save their industries. Hashikae also contained plenty of satire. Figures with medicine for heads representing doctors and medicine sellers are shown defending Hashika dōji by trying to hold back the angry mob. These industries thrived during outbreaks, and so they were thought not to want the disease defeated. A T A H D アマビコ : varies depending on the kanji used : amabiko nyūdō : oceans : unknown A : Amabiko are mysterious yōkai which emerge from the sea to deliver prophecies. They are ape-like, with protruding mouths, large round eyes, and big ears. Their bodies are covered in thick, long hair. They are usually depicted with three legs, although there are four-legged amabiko as well. B : Very little is known about amabiko as they only appear for a short time. They live in the seas around Japan and have been spotted in Kyūshū as well as along the coast of the Sea of Japan. Sightings continued throughout the latter half of the Edo period and into the Meiji period. I : Amabiko sightings follow the same pattern: an amabiko emerges from the sea, announces its name, and delivers a prophecy. It foretells a period of bountiful harvest followed by a period of disaster and disease. It instructs people to copy its image to use as protection. Then it disappears. O : uring the latter half of the 19th century, Japan experienced several epidemics. It was believed evil spirits were responsible for spreading disease, and an effective way to keep them away was to scare those spirits away by displaying pictures of powerful good spirits. The Edo period saw multiple prophetic savior yōkai who follow the same pattern as amabiko. These yōkai all appear briefly (usually from out of the sea), deliver a prophecy, and then vanish. Newspapers circulated these stories with illustrations of the yōkai so that people could hang them in homes as protective charms. Of the other amabiko-pattern yōkai (including amabie, arie, hakutaku, hōnengame, jinja hime, kudan, and others) amabie’s story and physical description are so similar to amabiko’s that they may be the same yōkai. The name amabie may have arisen from confusion between the characters コ (ko) and エ (e), which look similar in handwritten script. As amabiko’s name is usually written phonetically with katakana rather than kanji, its meaning remains vague. However, it is sometimes written using kanji, and the meaning changes from source to source. 尼彦 (nun boy), 天 彦 (heavenly boy), 海 彦 (sea boy), ⾬ 彦 (rain boy), and 天 ⽇ ⼦ (sunlight child) are some of the many ways to write amabiko. A T H D アリエ : none; this is its name : oceans : unknown A : Arie are prophetic aquatic yōkai with bulbous bodies covered in shiny scales. They somewhat resemble sea lions. They walk on four legs, and have long, thin tails. Their extended necks stick straight up from the center of their bodies, and they have hairy manes. B : Little is known about arie as there is only one recorded sighting. However, they fit the amabiko pattern of yōkai. They live in the ocean, can speak and deliver prophecies, and are powerful good spirits whose image alone is enough to repel evil and sickness. O : The only recorded arie sighting appeared in Kōfu hibi shinbun on June 17, 1876. The report was virtually identical to many other aquatic prophetic yōkai which appeared in the latter half of the 19th century. The article was printed along with an illustration of the arie. L : A strange creature was sighted in the waters off Higo Province (present-day Kumamoto Prefecture). After nightfall, the creature emerged from the water and began walking along the roadside calling out to people. Passersby were scared, so nobody approached the creature. Eventually the flow of traffic died out. A government official heard the rumors about the strange creature. He went to see it for himself. When he approached the creature, it spoke to him: “I am the leader of the scaled beasts of the sea. I am called arie.” The creature then foretold a six-year bumper crop and an outbreak of cholera. He informed the official that anyone who hung up its image and prayed to it would be protected from the disaster. After delivering its message the arie went back into the sea and was never seen again. H T A H D 豊年⻲ : fruitful year turtle : kame onna (“turtle woman”) : oceans : unknown A : Hōnengame are aquatic yōkai with fortune-telling abilities. They live in the seas around Japan. Hōnengame have bodies of large turtles, with broad, hairy tails protruding from their shells. They have heads of human women with long, flowing black hair. Horns often sprout from the tops of their heads. B : Hōnengame spend most of their lives deep in the sea, away from human activity. They rarely appear before humans, only coming to shore when they have an important message to deliver. I : Hōnengame deliver prophecies of bountiful harvests, which gives them their name. They also warn of coming epidemics, droughts, famines, or other disasters. Like many prophetic marine yōkai, their image was thought to have powerful protective abilities. Hōnengame illustrations printed in newspapers or sold as talismans and charms were believed to protect against disease and evil spirits. O : A hōnengame sighting was recorded in 1669. A turtle-like creature calling itself kame onna appeared on the shores of Echigo Province (present-day Niigata Prefecture). Its body glowed brilliantly, attracting a crowd of people. As they approached the creature, it spoke to them. It foretold a bumper crop which would be followed by an epidemic. It also informed them that if they were to hang its image in their homes and pray to it morning and night, they would avoid illness. Then the kame onna slipped back into the sea and was not seen again. A newspaper from 1839 describes a sighting from Kishū (presentday Wakayama and Mie Prefectures). On the 14th day of the 7th month, a hōnengame was captured alive by fishermen. It was measured as having a girth of 5.5 meters and a length of 1.71 meters. An illustration of the creature was circulated and used as a talisman against evil. U T H D 海出⼈ : person from the sea : oceans : unknown A : Umidebito are prophetic yōkai which live in the seas off Japan. They have the heads, arms, and torsos of human women and scales like fish or dragons. The lower half of their bodies are hidden inside large spiral shells like a conch or a sea snail. B : Umidebito spend their lives deep in the sea. They occasionally surface to deliver prophecies foretelling bountiful harvests and devastating illnesses. I : When umidebito surface, they ride the waves using their shell like a boat. They call out to humans, searching for someone to whom they can deliver their message. O : Umidebito follow the common pattern of prophetic yōkai. They emerge from the sea to deliver their warning and offer salvation in the form of their image. This theme was prevalent through the Edo and Meiji periods, increasing dramatically in the latter half of the 19th century. L : An umidebito was sighted in Fukushimagata, Echigo Province (present-day Niigata Prefecture) in mid-April of 1849. According to reports, a bright light was spotted during the evening off the shore. Witnesses heard a woman’s voice call out from the light. Most people were too afraid to approach the light, but a brave samurai named Shibata Chūsaburō approached the light to see it with his own eyes. As he approached, the voice said: “I am an umidebito who lives in these seas. A bumper crop lasting five years will begin this year in every province. However, in November, a great sickness will spread and kill 60% of the population. Those who see me or my picture will be spared. Go quickly and spread this message!” After delivering her prophecy the umidebito vanished. Y T H D ヨゲンノトリ : prophecy bird : holy mountains : unknown A : Yogen no tori are prophetic birds which resemble twoheaded crows. One head is black and the other white, both of which can speak. B : Yogen no tori are holy animals, sent by the gods when there is an important message to deliver. I : Yogen no tori deliver sacred messages to humanity. Merely an image of them is powerful enough to keep away diseasespreading evil spirits. Regularly looking at a picture of a yogen no tori is said to protect you from harm. O : Yogen no tori belong to the popular Edo period phenomenon of prophetic yōkai warning of outbreaks and offering their image as protection. Infectious diseases like cholera are spread by invisible means, and for most of history there were no known cures or effective methods of prevention. Amulets, talismans, and images of holy spirits might not have done much to prevent sickness, but the desire to cling to any promise of salvation in the face of an unknown threat is understandable. L : A cholera outbreak struck Japan in the summer of 1858. During the outbreak, a government official named Kizaemon from Kai Province (Yamanashi Prefecture) discovered the legend of the yogen no tori. He reported it in Bōshabyō ryūkō nikki, a journal which detailed the outbreak. According to his report, a yogen no tori was sighted in December of 1857 near Mount Haku in Kaga Province (Ishikawa Prefecture). The bird proclaimed, “Around August or September of next year a disaster will occur, killing 90% of the world’s population. Those who gaze upon my image morning and night and believe in me will be spared from this suffering.” Kizaemon believed the yogen no tori to be a messenger from the gods. He declared it to be a symbol of the great power of Kumano Gongen. An illustration of the bird was printed alongside the report so people could see it and receive its divine protection. K T A shūgen 狐の嫁⼊り : a fox’s wedding; sun shower : kitsune no yometori, kitsune no kon, kitsune no A : Kitsune no yomeiri are beautiful yet eerie processions which happen before the wedding of a kitsune. They appear as long strings of phantom lights stretching over a large area. Kitsune no yomeiri resemble old fashioned Japanese bridal processions, in which the bride would travel to her new home among a parade of lanterns. B : Kitsune weddings usually take place during the deep quiet of night, but they can also take place in the day during a sun shower. Rain falling while the sun shines was said to be a kitsune trick meant to send humans running indoors so that they could hold their wedding away from prying eyes. O : Whenever rain and sun appeared together, people believed that kitsune were having a wedding nearby. Today, the common Japanese phrase for a sun shower is kitsune no yomeiri. L : A folktale from Miyazaki Prefecture describes a kitsune no yomeiri. A man was traveling in the mountains one sunny day, when suddenly it began to rain. “A kitsune must be getting married!” he thought. He noticed a beautiful woman ahead of him on the road. She turned and smiled in his direction. He followed her, and every time she turned and smiled at him, his heart fluttered. The woman broke a few branches from a tree and slid them into her hair. They turned into beautiful hairpins. She traced her fingers along a large tree trunk and circled around it. Her clothing transformed into a fabulous white bridal kimono. “This woman must be a kitsune!” the man thought as he stared in amazement. The woman continued on to a bamboo grove. Countless kitsune began to emerge. They carried long ornate chests and a palanquin which they brought to the bride for her to enter. Each guest was wearing a splendid kimono decorated with a family crest. “I was right! It’s a kitsune wedding!” The man was excited to witness something so rare. The man followed the procession deeper and deeper into the mountains. It arrived at a large manor with a thatched roof. The kitsune entered the manor. “This must be where the ceremony will take place!” thought the man. He searched for a way to spy on the ceremony, finding a small hole high up in the wall. He climbed upon a large stone step and stretched his legs to reach the hole. From there he could see the manor’s interior. It was decorated with expensive dining tables, and kitsune were seated around them. “Why, it’s just like a human wedding!” he thought as he watched the ceremony. After some time, the man grew tired. He stepped down from the peephole and lit his pipe. As he puffed, the scenery changed before his eyes. What was a great straw-thatched manor just a moment ago became a wooden shrine. The stair he had been standing on became the pedestal of a great stone lantern. And the hole in the wall became the hole of the stone lantern. The guests and tables were nowhere to be seen. There was no sign that anything had taken place at all. Even though he was aware they were kitsune, he had still been bewitched by their magic. Y T A H D 妖狐 : strange fox : kitsune, bake gitsune : forests, fields, and mountains : omnivorous; especially fond of fried tofu A : Yōko literally means “strange fox.” It refers to magical foxes in the context of folklore. Normally they are referred to simply as kitsune; although terms like yōko and bake gitsune are helpful to distinguish between the animals and the folklore. Yōko appear essentially identical to ordinary, non-magical foxes. As they grow older and more powerful, they undergo physical changes. For every hundred years of life they acquire an additional tail, up to a maximum of nine. B : Kitsune have a complex society which mirrors human society. They are divided into two main categories: yako and zenko. Yako are wild kitsune who have no master. They are not concerned with social advancement, and enjoy playing tricks on humans. Zenko are good kitsune who serve the god Inari. They continue to acquire new social ranks and honors as they age, and they do not harm humans. Kitsune are most famous for their ability to change forms. To learn this skill, young kitsune place an object on their head, face the Big Dipper, and pray. The object is usually a human skull or a bone from a cow or a horse. Other objects may be incorporated into this spell to improve the disguise. For example, to disguise itself as a cook a kitsune might place a piece of kitchenware on its body. To transform into one of their favorite disguises–a beautiful young woman–they use leaves, a lily pad, or duckweed, which transforms into long, elegant hair. As kitsune grow more powerful, they no longer need props to create complex disguises. F F Almost every village in Japan has stories about kitsune creating mischief or performing good deeds for the locals. Some kitsune are well known across entire regions. Two kitsune in particular are so famous that everybody knows their names: Kuzunoha and Tamamo no Mae. Kuzunoha was kind and loving, and is a perfect example of a zenko, or good kitsune. She fell in love with a human and gave birth to Abe no Seimei, who became Japan’s most powerful sorcerer. Tamamo no Mae, on the other hand, was as wicked as kitsune can be. She tried to murder the emperor and destabilize the entire country, but she was thwarted by Abe no Yasuchika, a descendant of Abe no Seimei. Tamamo no Mae is remembered as one of the most dangerous yōkai ever to exist. Z T A H D 善狐 : good fox, virtuous fox : reiko, inari kitsune, osakitōge : forests, fields, mountains, and shrines : omnivorous A : Zenko are good kitsune who serve the gods and perform good deeds. B : Zenko society is extremely complex. It mirrors human society, with families and tribes, ranks, and various levels of awards and degrees. Sources disagree on the exact structure of zenko society. According to one common classification, Zenko are divided into five groups based on fur color: tenko (heavenly foxes), kinko (gold foxes), ginko (silver foxes), byakko (white foxes), and kokuko (black foxes). Another classification divides them into three social ranks with no regard for coloring: tenko (heavenly foxes), kūko (sky foxes), and kiko (spirit foxes). Still other classifications exist. Individual shrines such as the Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyōto often have their own degrees and ranks to bestow upon hard-working zenko. The one area where everyone agrees is that zenko stand in stark contrast to yako (wild foxes). Evil behavior frequently attributed to kitsune is always the work of yako, not zenko. Whereas yako have no interest in advancement in kitsune society, zenko work hard to improve themselves and increase their social standing. Zenko may occasionally play tricks or pranks on people, but they do not seriously harm or kill humans. Zenko serve the gods as messengers, facilitating communications between humans and kami. They are most often found in the service of the Shintō deity Inari or the Buddhist Dakini. Zenko can even be enshrined as gods themselves, or as manifestations or emanations of higher deities. O : Kitsune monogatari, part of the Edo period essay collection Kyūsensha manpitsu, is a well-known source on the structure of kitsune society. It claims to be the recorded words of a kitsune who possessed a human and discussed the different tribes of zenko and the ranks of kitsune society through its host’s mouth. The kitsune made a very clear point that there was a distinction between benevolent zenko and wicked yako. Y 野狐 T : wild fox A : nogitsune, yakan H : forests, fields, and mountains D : omnivorous; fond of wax, oil, sake, and lacquer; also feed on human life force A : Yako are low-ranking, wild kitsune that do not have divine souls or serve as messengers of the gods. They are known for tricking, tormenting, and possessing humans. All wicked kitsune are yako. However, not all yako are necessarily wicked. B : Yako are the lowest-ranking members of kitsune society. They are comfortable in this position and do not aspire to increase their standing. Yako are cautious and have a keen danger sense. They dislike bright light and hide from the sun. They are afraid of bladed objects and run from swords and knives. They are frightened of dogs as well. A yako disguised as a human might accidentally reveal their true form when startled by a barking dog. Yako recognize signs of human activity and hide when possible. However, they often sneak into villages at night to steal favorite foods: wax candles, lamp oil, lacquer, alcohol, and fried tofu. I : Yako are notorious tricksters. One of their favorite tricks is transforming into humans or objects. They use this power to play pranks, steal things, or punish those who have hurt them. They also seduce foolish men, using sex to drain their life force and increase their own power. Yako are famous for kitsunetsuki–possession by a kitsune. Sometimes they do this to punish humans they dislike. Other times it is simply for their own amusement. They prefer to possess women. They feed off women’s life force, draining energy from their victims. Despite frequent conflicts, yako occasionally have positive relationships with people. Stories tell of yako repaying people who do them good deeds. However, yako are notoriously unreliable. If you ask one to guard an object, it will only do so for a short time before it forgets its promise and wanders off. There are sometimes marriages between men and yako disguised as beautiful women. However, when the disguise is inevitably discovered these stories end in tragedy. O : Yako are known by different names. The most common one–nogitsune–is an alternate reading of the kanji in its name. Yakan is more archaic, and originally referred to a different animal. Yakan are beasts from Buddhist scriptures. The term literally means “wild dogs.” They are cunning, and resemble small, yellow dogs with fluffy tails. They can change their shape, and their true form is unknown. Yakan live in packs and howl at night like wolves. In the original Sanskrit yakan referred to jackals. Jackals were viewed as servants of evil spirits, as they linger around burial grounds and eat carrion. As jackals do not exist in China, when Buddhism was transmitted to China, yakan were assumed to be foxes, martens, or wild dogs. In Japan, yakan were associated with foxes and merged with native kitsune folklore. Thus, the evil behavior of jackals in Indian and Chinese folklore became the wicked deeds of kitsune. B T A H ⽩狐 : white fox : shirogitsune : forests, fields, mountains, and shrines A : Byakko are kitsune with pure white fur. They can have anywhere from one to nine tails depending on their age. B : Byakko are the most common of the tribes of zenko, or good kitsune. They are associated with Shintō and devote their lives to the service of the deity Inari. I : Byakko are revered by humans as messengers or even incarnations of the gods. Statues of byakko are frequently found as decorations inside of Inari shrine grounds. Images of byakko are often sold by shrines as charms. F L White-furred kitsune are often referred to by the name myōbu, an official rank for ladies in the imperial court. During the Heian period, a noblewoman named Shin no Myōbu regularly visited the Fushimi Inari Shrine and climbed to the top of Mount Inari to worship. Her devotion impressed an old kitsune named Akomachi who lived in the shrine. Akomachi offered protection and divine wisdom to Shin no Myōbu. Thanks to the kitsune’s divine guidance, Shin no Myōbu improved her standing in the court and was awarded a higher rank. She granted her old rank of myōbu to Akomach in gratitude. Since then, the kitsune of Mount Inari have been known as myōbu, in honor of the rank bestowed upon Akomachi. K T A D ⿊狐 : black fox : kurogitsune, kuroko, kokko, genko : forests, fields, mountains, and shrines A : Kokuko are rare kitsune who show themselves only during the reign of a peaceful leader. They have thick, black fur and are slightly larger than other kitsune. They have from one to nine tails depending on their age. Kokuko live in northern climates like Siberia and Hokkaidō. They seldom appear in Japan south of the Tōhoku region. B : Kokuko are one of the five families of zenko. They have pure, good hearts and stand in contrast to yako. In onmyōdō, kokuko are associated with the cult of the North Star. They are said to be incarnations of the Big Dipper. They also serve Inari, although they are far less common than byakko. L : In 1771, the lord of Hokkaidō, Matsumae Michihiro, married a noblewoman from Kyōto. His bride was a devoted worshipper of Inari, and frequently visited Inari shrines where kitsune made their homes. When she moved to be with her husband, many kitsune followed her. Unfortunately, she died soon after marrying. The kitsune who had accompanied her returned to Kyōto. One day, Michihiro’s retainers went hunting in the mountains. They saw a rare black kitsune and shot it. Michihiro was pleased when they brought the creature back. But shortly after that, strange things began to happen. Michihiro offered the rare kitsune’s meat as a present to one of his retainers. After eating it, the retainer became sick. He was immediately struck deaf. Death soon followed. Michihiro had the fur of the kitsune hung out to dry. However, every night a kitsune appeared at the castle and demanded the skin be returned. When Michihiro heard of this he refused. One morning after that, the skin was missing, torn off the drying frame. Then, local fishermen began complaining they could no longer catch herring. Michihiro was troubled. He believed the dead kitsune placed a curse on his domain. He consulted a temple and had the priest perform one hundred nights of prayers for the kitsune. On the ninety-ninth night, the priest had a vision. A black kitsune appeared to him, explaining it was one of the kitsune who came from Kyōto. It had made a family with a local kitsune and didn’t return with the others. After being killed by Michihiro’s retainers, it was unable to pass on. It remained as a vengeful spirit. It told that priest that if they would build a shrine, it could pass on and serve the area as a guardian spirit. The priest told Michihiro what the kitsune had told him. Michihiro built an Inari shrine for the black kitsune nearby and enshrined it there. That shrine exists today: the Genko Inari Shrine inside the Kumano Shrine in Matsumae, Hokkaidō. G T A H A Dakini. 銀狐 : silver fox : gingitsune : forests, fields, mountains, temples and shrines : Ginko are silver-furred kitsune who serve the goddess I : Ginko symbolize the moon, and serve as a counterpart to kinko, who symbolize the sun. Ginko and kinko are two of the five families of zenko. While byakko and kokuko are associated with the god Inari and Shintō, ginko and kinko are associated with the goddess Dakini and Buddhism. They are pure, holy spirits. They represent the moon and sun and usually work together. K T A H A ⾦狐 : gold fox : kingitsune : forests, fields, mountains, temples and shrines : Kinko are golden-furred kitsune who serve Dakini. I : Kinko symbolize the sun, while their counterparts ginko symbolize the moon. I D When Buddhism was brought into other countries, it merged with local belief systems to make it more acceptable to the populace. By the time Buddhism gained wide acceptance in China, it had absorbed many features of Chinese folk religion. In Japan, this mixture of Chinese and Indian Buddhism was syncretized further with Shintō. Each kami was said to be a local emanation of one of the many buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other spirits in Buddhist cosmology. Major figures syncretized based on similarities in iconography, stories, or features of their worship. The Chinese depiction of Dakini and the Japanese Inari shared enough similarities that they were associated with each other. The syncretization of Buddhist figures with Shintō deities can be a controversial subject. There are some who say that Inari and Dakini are two aspects of the same figure. Others say Inari and Dakini are completely different beings who were confused with each other. D T A H D 荼枳尼 : none; a transliteration of the Sanskrit term dakini : Dakiniten, Daten, Shinko’ō, Kiko Tennō : the sky : human hearts, blood, and flesh A : Dakini is an esoteric goddess and an important figure in Shingon Buddhism. She is the Japanese interpretation of dakini sky spirits from Indian cosmology. In Shintō-Buddhist syncretism she is associated with the kami Inari. Dakini is usually depicted as a beautiful, half-nude woman carrying a wish-granting jewel and riding a white fox. B : Dakini serves Benzaiten, the goddess of wisdom, and Daikokuten, the god of grain. She is said to be willing to grant any wish. I : Dakini is revered across Japan as a goddess of food, grain, foxes, and good fortune. She was an important goddess to the nobility and samurai classes during the Middle Ages. Both the shōgun and the emperor venerated Dakini, believing that failure to do so would bring an end to their rule. Secret rituals relating to Dakini worship were passed down orally through the imperial household and remain an integral part of imperial enthronement ceremonies. The deepest secrets of her esoteric worship are said to grant unlimited power. Among the gifts that Dakini granted her worshipers was knowledge of the future. Also was the ability to trap kitsune and use them to possess enemies. O :Dakini were originally a race of wrathful Indian sky spirits. They served Kali and looked like beautiful, nude women. Dakini were energetic, wise, and muse-like. They carried swords for cutting out hearts. Dakini feasted upon human flesh and drank blood from skulls. When they listened to the Buddha’s teachings, they converted to Buddhism. Along with this came a promise to stop killing people, and to feast only upon the meat of the recently dead. To ensure they wouldn’t starve, dakini were granted the power to see six months into the future. This way, they could wait near people who were going to die soon. When they died, dakini could feast upon their flesh before other carrion-eating demons arrived. Because they feed upon carrion, dakini were associated with jackals. Jackals did not exist in China, but they were described as clever, wicked, magical beasts who look like dogs and feed on humans. That description matched Chinese folklore about foxes who disguise themselves as beautiful women and feed on human life force. Jackals became synonymous with foxes. Dakini also became linked with foxes. As Buddhism was transmitted though India and China to Japan, dakini fused with other religious and folkloric concepts. In Japan, dakini changed from a race of sky spirits into a single figure resembling both a goddess and a demon. As a result of her long and complicated history, and the esoteric nature of her religious practice, Dakini is known by many different names. She is called Shinko’ō (“Dragon Fox Queen”), Kiko Tennō (“Noble Fox Empress”), and many more due to her syncretism with Inari. L : Genpei seisuiki, an extended narrative of the Tale of the Heike, describes an encounter with a servant of Dakini. Long ago, an impoverished young samurai named Taira no Kiyomori went hunting and shot a fox. To his surprise the fox transformed into a beautiful woman. She explained that she was a servant of Dakini. She promised that if Kiyomori spared her life, she would see to it that all his wishes would come true. Kiyomori let her go free and began to pray to Dakini. Sure enough, Kiyomori’s luck soon changed. His family rose to prominence and he became wealthy and powerful. The Taira became the most powerful samurai clan in Japan for a time. Kiyomori’s success is often credited to Dakini’s influence. A T A H D 阿紫霊 : “Azi” spirit : ashi, ashireiko : forests, fields, and mountains : omnivorous A : Ashirei are the lowest-ranking and youngest kitsune. This rank is held from infancy until one hundred years old. Consequently, the vast majority of kitsune belong to this rank. B : Around the age of fifty, kitsune begin ascetic training to develop magical skills. They travel to holy mountains and study ancient occult practices involving worship of the sun, moon, and stars. Young kitsune develop their shape shifting abilities at this age. By the time an ashirei has reached a hundred years of age, it has honed its magical skills enough to be promoted to the next rank: chiko. I :Because it is the most populous rank, kitsune which humans encounter are usually ashirei. Before they develop sufficient magical powers, ashirei are easily caught in snares, injured, or even killed by hunters and dogs. Only after a great deal of magical training can they pose a threat to humans. Once ashirei understands magic, they become dangerous to humanity. They may seek revenge against people who wronged their family. O : The term ashirei comes from Azi, an evil fox spirit from a 3rd century Chinese legend. Azi is pronounced Ashi in Japanese. A soldier named Wang Lingxaio was repeatedly lured away from his post by a beautiful woman named Azi. One day, he deserted his post completely. Wang’s commanding officer, Chen Hao, suspected the woman was a demon. Chen gathered his men and dogs and tracked Wang to a cave. They found him lying on the floor inside, half transformed into a fox. He was helpless, repeatedly calling out for Azi. After he was rescued, Wang confessed that the pleasure of being with Azi was incomparable to anything he had ever experienced. Azi’s name became synonymous for a beautiful, honey-mouthed temptress with a wicked heart and a cruel lust for torturing men. Her legendary seduction and destruction of a good man became the pattern for countless future kitsune stories. C T A H D 地狐 : earth fox : chikojin : forests and wilderness, often found near human areas : omnivorous A : Chiko are kitsune with a considerable amount of magical power. This is the second rank of kitsune society, above ashirei. Chiko have physical bodies and still resemble ordinary foxes, but they sprout additional tails as they age. The oldest and most powerful chiko can have up to nine tails. B : After one hundred years of age, a kitsune can advance from ashirei to chiko. Most chiko are between one hundred and five hundred years of age. For kitsune who wish to continue to advance, this is a period of intense ascetic practice. Chiko is the highest rank which yako can achieve. No matter how many years they may live, no matter how many tails they grow or how powerful they become, a yako will never advance beyond this social rank. This does not necessarily limit their power. Tamamo no Mae, the most famous and powerful nine-tailed kitsune, only held the rank of chiko. I : Chiko may be wicked, beneficent, or indifferent towards humans. All chiko are powerful; how they use this power depends upon whether they want to continue to rise in kitsune society or not. Chiko who advance to higher ranks must give up wicked deeds such as playing pranks on humans or draining their life force in order to gain more power. K T A H D 気狐 : spirit fox : senko (wizard fox) : usually found near Inari shrines : none; they no longer need food A : Kiko are between five hundred and a thousand years of age. Spiritual beings without true physical bodies, they can appear in many different forms. Kiko is the third rank of kitsune society, standing above ashirei and chiko, and below tenko and kūko. All kiko are zenko who serve the kami Inari. Most are white-furred (byakko) kitsune, but black (kokuko), gold (kinko), and silver-furred (ginko) kiko also exist. B : At around five hundred years of age, good chiko may advance to the next rank of society and become kiko. They shed their physical bodies, becoming spiritual entities. Their duty is to act as servants and messengers of the Shintō deity Inari Ōkami. The vast majority of kitsune in Inari’s service are kiko. Their magical skills are vaster than those of chiko, but they still have a great deal of service and training to complete before attaining the higher ranks of kūko and tenko. I : While lower-ranking kitsune like chiko are known for taking human form to drain the life force of humans, kiko are are less likely to act maliciously. Instead, kiko often take human form to help people. Some of them even fall in love with humans and live with them in disguise for many years. One of the best-known stories of a kitsune falling in love with a human is Kuzunoha, the mother of Abe no Seimei. K T A H D 空狐 : sky fox : Inari kūko : the sky : none; they no longer need food A : Kūko are ancient kitsune who have risen to the highest levels of kitsune society. A kitsune takes the rank of kūko after reaching three thousand years of age. As being of pure spirit, they do not have physical bodies. When they appear, they take on a rather human-like appearance, with ears resembling a fox, and no tails at all. They are telepathic, clairvoyant, and can even see the future. Their level of magical power is the highest it will ever be–on par with the gods. B : Although they are the oldest and most powerful kitsune, kūko are the second-highest ranked in kitsune society. Tenko are younger but ranked higher. This is because after three thousand years, kūko have reached a sort of retirement age where they are no longer working in the service of Inari. Younger kitsune still actively serve the gods, while a kūko’s duties are more like a privy council or a venerated elder. I : When kūko interact with human beings, it is only to do good. They might increase the prosperity of a temple or a household. They might help a good and honest person achieve fame for their skills. Or they might possess a pure-hearted but foolish person in order to teach them a lesson. When a kūko possesses a human, it doesn’t cause mental disorder or sickness in the way commonly associated with kitsune possession. L : The Edo period book Kyūsensha manpitsu tells a story of an encounter with a kūko. A kitsune who had been living in Kyōto for a long time decided to make a journey to Edo. Along the way, he stopped to rest at the house of a samurai named Nagasaki Genjirō. He decided to “borrow” the body of one of Genjirō’s servants–a sickly fourteen-year-old boy. He spoke through the boy and described to Genjirō the different ranks of kitsune society and the differences between good and bad kitsune. He explained that while yako often harm humans, zenko only possess stubborn or foolish humans to teach them important lessons. Zenko use their magic to help people. The kitsune explained that he was, in fact a zenko, merely inhabiting the servant’s body temporarily. The kūko remained in control of the servant’s body for five days. During this time, he entertained Genjirō’s household and neighbors with tales of the Genpei War, the Battle of Dannoura, and the Battle of Sekigahara. After everyone had been thoroughly entertained, the kūko departed the servant’s body–but not before he used his magic to cure the diseases and ailments the boy had been suffering from. As a gesture of thanks for Genjirō’s hospitality, the kūko left behind a signed calligraphic scroll containing the secret inner teachings of Hakke Shintō. T T A H D 天狐 : heavenly fox : amatsu gitsune : the sky : none; they no longer need food A : Tenko are good kitsune at least one thousand years old who possess god-like divine powers. Tenko is the highest rank in kitsune society. They can fly, they have clairvoyance, and they can see into the future. Tenko are spiritual beings without physical bodies. Their actual appearance depends upon the form they decide to take. They often appear as beautiful human-like goddesses with vulpine features: gold, silver, or white fur, and multiple (usually four) bushy tails. B : The rank of tenko is achieved after one thousand years of age by kiko who have been pure and have ceased to commit all wicked deeds. Their level of power is practically indistinguishable from a god’s. Only kūko are older and more powerful than tenko. However, the rank of kūko is something like retirement for kitsune; an elder stateman. Tenko is the pinnacle of kitsune society. I : Tenko are treated as gods by humans. They sometimes grant boons and favors to people who revere them. Like all kitsune, tenko can possess humans, but they do not do so to play pranks. A human possessed by a tenko gains the tenko’s power of clairvoyance and can predict future events. T =T ? In Nihon shoki, it is recorded that in 637 CE a meteor shot across the sky above Japan from east to west. As it fell, it shook the earth like thunder. A monk named Min who witnessed the event explained that it was not a shooting star, but an amatsu gitsune. The characters he used to write amatsu gitsune were the same characters used to write tengu. His explanation has become a source of debate over whether tenko and tengu are related to each other. Some sources say that tengu are the oldest tenko (i.e., kūko), while others dismiss this theory as nonsense. M T 政⽊狐 : Masaki the fox A : Masaki gitsune is powerful nine-tailed kitsune who appears in Kyokutei Bakin’s epic novel Nansō satomi hakkenden (“The Chronicles of the Eight Dogs”), finished in 1842. L : Long ago, when Kawagoi Moriyuki oversaw Shinobu no Oka Castle, a pregnant kitsune took shelter beneath the floorboards. Moriyuki’s kind wife let her stay there and give birth. When a footman named Kaketa Wanazō captured and killed the kitsune’s mate, Moriyuki’s wife took pity on the kitsune. She slipped her food to help raise her young. The cubs grew up healthy and left the nest. Then, the kitsune began to plan her revenge on Wanazō. Wanazō was having an affair with Masaki, the nanny of Moriyuki’s infant son Takatsugu. One night, Wanazō and Masaki secretly slipped away from the castle. The kitsune followed them. Once away from the safety of the castle, she transformed into a bandit and threatened Wanazō with a sword. Wanazō and Masaki ran for their lives. They slipped off the road into the river and drowned. The kitsune had her revenge, but she felt bad that the young Takatsugu lost his nanny. To repay the kindness Takatsugu’s mother had shown her, she transformed into Masaki and took her place as Takatsugu’s nanny. For two years Masaki the kitsune raised Takatsugu. One day, Masaki dozed off and part of her disguise failed. The young Takatsugu was startled. He cried out, “Nanny’s face turned into a dog!” Masaki knew if people learned that Takatsugu had been raised on beast’s milk, it would bring shame on him as a warrior. With tears in her eyes, she fled the castle before anyone could learn of her deception. Masaki moved to a field in Ueno and contemplated her life. Although she had lived for hundreds of years, she had not lived a meritorious life. Her divine power was low. She had killed people–even though they were her enemies. Masaki dedicated her life to charity and helping others. She disguised herself as an old woman and opened a tea shop. She sheltered travelers from the heat and cold. She gave refuge to orphans. She talked star-crossed lovers out of suicide pacts. She clothed and fed the hopelessly poor. Over twenty years, Masaki saved the lives of 999 people. In that time, she reached her one thousandth birthday. Her tail split into nine strands, and her fur became white. Masaki became clairvoyant, which is how she sensed that Takatsugu was in danger. Masaki summoned all nearby kitsune. They transformed into warriors and followed Masaki to rescue Takatsugu. After saving him, Masaki revealed her identity. She told him of their past connection and informed him that through her years of hard work and virtue she had earned the favor of the emperor of heaven. She was to transform into a koryū (“fox dragon”)–a kitsune so powerful and virtuous that it is indistinguishable from a dragon–and ascend to heaven, leaving the earthly world behind. Masaki left the teahouse and dove into Shinobazu Pond. A moment later, clouds formed, and rain began to pour from the sky. As the storm blew, a great white kitsune dragon emerged from the pond. The tea shop and all its tea utensils and furniture were sucked up into the sky. After a few moments, the thunder, wind, and rain subsided, the sky cleared, and Masaki disappeared. Y ⼋尾狐 T : eight-tailed fox A : Yao no kitsune are powerful kitsune with eight tails. O : An encounter with a yao no kitsune was recorded by Kasuga no Tsubone in Tōshō daigongen notto, a document of praise and thanks to the deified founder of the Edo shogunate Tokugawa Ieyasu. L : In 1637, Tokugawa Iemitsu came down with a terrible illness. As he lay on his deathbed, he experienced a revelation. He dreamed an eight-tailed kitsune appeared to him, sent from Nikkō Toshōgu. The kitsune told Iemitsu that he would recover from his sickness, and then it vanished. When Iemitsu awoke his fever was gone. He quickly recovered, just as the kitsune predicted. The eight-tailed kitsune from Nikkō Toshōgu and Iemitsu’s extraordinary recovery served as evidence of the divinity of Iemitsu’s grandfather. Iemitsu had a scroll commemorating the yao no kitsune commissioned from the shogunate’s official painter Kanō Tan’yū. O T ⼄姫狐 : princess fox A : Otohime gitsune is a kitsune who lived on a mountain called Hatahikiyama in what is now the village of Kyūhirota in Kashiwazaki City, Niigata Prefecture. She was known to the villagers only by her disembodied voice heard in the woods–nobody had ever seen her true form. Otohime was worshiped by the villagers as a goddess. B : Otohime was clairvoyant. Whenever the villagers called out to her from the base of her mountain, she answered their questions. L : When a farmer lost one of his tools, he approached the foot of Hatahikiyama and asked Otohime for help. A voice came from the woods and said that he had left it next to his shed. When some food was stolen from the village, Otohime’s voice told villagers the name of the thief and where he was hiding. The villagers recovered their food and chased away the thief. Soon, thanks to Otohime’s help, there were no wicked people left in the village. One autumn, a villager’s garden was torn up by wild animals and most of his vegetables were destroyed. Fearing he would run out of food during the winter, he set some traps deep in the woods to catch the beasts that destroyed his crops. Soon, the farmer heard a voice call out from deep in the forest. It was a call for help. It was the unmistakable voice of Otohime. The man hurried into the woods. He climbed up the mountain to where he heard the voice. Finally, he reached the exact spot where he had set his traps. There, caught in one of his snares, was the body of a large, beautiful, white-furred kitsune. But it was too late; she was dead. The voice of Otohime was never again heard in the village. O T おとら狐 : Otora the fox A : Otora gitsune is a one-eyed, three-legged kitsune from Aichi Prefecture. He is best known for kitsune tsuki–kitsune possession of a human. Otora gitsune was particularly renowned for possessing the sick and infirm. He had a powerful personality. Humans possessed by him adopted his mannerisms. B : People possessed by Otora gitsune exhibit a few telltale signs. They experience an excess of discharge from their left eye. Their left leg aches unexpectedly. They talk endlessly about the Battle of Nagashino, that time they got shot, and other personal adventures that they never experienced. I : Otora gitsune could usually be exorcised by a priest. However, there were times when his possession was exceptionally strong. In those cases, victims were recommended to travel to the Yamazumi Shrine in Hamamatsu for an exorcism. This is because Yamazumi Shrine is dedicated to wolves. Many rituals performed there invoke the power of wolves to chase away sickness and evil spirits. As kitsune are terrified of dogs and wolves, these exorcisms are particularly effective at curing kitsune tsuki. O : Otora gitsune lived in the Inari shrine grove at Nagashino Castle. After the Battle of Nagashino, the castle was burnt to the ground. Its Inari shrine was abandoned and never rebuilt. Otora gitsune became enraged and turned his vengeance against locals by possessing them. His first target was a woman named Otora, the daughter of a wealthy family. It is from her that the Otora gitsune got his name. From then on, Otora gitsune possessed villager after villager, causing mischief across the region. L : Otora gitsune became one-eyed as a result of the Battle of Nagashino. He was observing the battle from his grove when a stray bullet struck his left eye. There are a few stories about how he lost his left leg. Some say he was eavesdropping on a meeting of generals deep in Nagashino Castle when his shadow fell across the paper sliding door. The lord of the castle saw the shadow and, believing it to be a spy, swung his sword and severed the kitsune’s leg. Another version says that he transformed into a crow, perched on a wall, and cawed loudly every day. This annoyed a bowman who lived nearby. The bowman shot an arrow at the crow, severing its leg. Otora gitsune was killed by a hunter while napping on the banks of the Sai River in Nagano Prefecture. However, his legacy was carried on by his progeny. His grandchildren took up the name Otora gitsune and continued to possess people. They told their grandfather’s stories through human mouths. H T name ⽩蔵主 : literally “white storehouse keeper,” a Buddhist priest’s A : Hakuzōsu is both the name of a monk and the kitsune who killed him, took his place, and performed his duties faithfully. The story has been adapted many times over the centuries, with the names, places, and other details changing across different adaptations. O : Ehon hyaku monogatari places the story in Yamanashi Prefecture, at the base of Mount Atago. The kyōgen play Tsurigitsune is based on a 14th century version of this story from Shōrinji, a temple in Sakai, Osaka. L : Long ago lived a man named Yasaku. Yasaku made his living trapping foxes and selling their pelts in the market. An old, silver-furred kitsune lived in the mountains where Yasaku worked. The kitsune had lost all his friends and family members one by one to Yasaku’s traps until at last only he remained. He decided he would teach the trapper a lesson. The kitsune disguised himself as Yasaku’s uncle, a monk named Hakuzōsu. Then he paid Yasaku a visit. He scolded him for hunting foxes and asked him to stop. He preached the Buddhist precept that killing any living being is a grave sin. He referenced the legend of Tamamo no Mae, whose sins caused her to be transformed into a boulder as a punishment. He even gave Yasaku money in exchange for the rest of his snares. Yasaku agreed and promised to stop killing foxes. Pleased, the kitsune skipped back into the forest. However, the money did not support Yasaku for long. He quickly spent all he had been given. He visited his uncle to ask for more money. The old kitsune realized that if Yasaku spoke to Hakuzōsu his deception would be discovered. The kitsune went ahead of Yasaku and found the monk. He lured him into the forest and devoured him. Then he disguised himself as Hakuzōsu again. When Yasaku arrived, the kitsune scolded him for being wasteful and sent him away empty handed. For the next fifty years, the old kitsune lived in the temple as Hakuzōsu. He faithfully performed the monk’s duties every day. Nobody ever realized that Hakuzōsu was a kitsune in disguise. One day, a deer hunt took place at a nearby farm. Everybody in the village gathered to watch, including Hakuzōsu. However, when Hakuzōsu arrived, two of the hunters’ dogs smelled the kitsune and became agitated. They leaped upon Hakuzōsu and quickly ripped him to pieces. When the dogs were finally called off the old monk it was too late. All that was left was the torn body of an old, silverfurred kitsune. Although Hakuzōsu’s deception was exposed, the villagers feared that the kitsune’s spirit would return and curse them. They buried him in the shade of a nearby mountain and erected a small shrine. D T A 伝⼋狐 : Denpachi the fox : Konoha, Konoha Inari Daimyōjin A : Denpachi gitsune is a kitsune from Iidaka in Sōsa City, Chiba Prefecture. O : A kitsune named Konoha lived in a hole in the woods in Iidaka, near a major Buddhist seminary. Young men from all over eastern Japan went there to study. Konoha heard the young priests every day reciting their chants and performing their studies. He was intrigued. He wanted to study too. So Konoha disguised himself as a young man named Denpachi and slipped into the seminary, blending in with the other students. L : Every morning Konoha transformed into Denpachi and went to school early. When the other students and teachers arrived, Denpachi was already performing temple chores, sweeping floors and preparing meals. Denpachi was an exemplary student. He poured himself into his studies. He performed his ascetic training diligently and learned to comprehend the deepest esoteric mysteries. From time to time, he even instructed other students in some of the more difficult teachings. Denpachi came to be highly respected among his fellow students and the faculty. Though he was a diligent student, Denpachi was occasionally careless. Students and teachers discovered paw prints leading into and out of seminary buildings. Occasionally, leaves onto which Denpachi had copied the Lotus Sutra would be found in the gardens. Rumors spread that a kitsune was performing mischief at the seminary. Of course, nobody suspected Denpachi. For ten years, Denpachi continued to study diligently at Iidaka. One day, a high priest named Saint Nōke was installed as the new headmaster of Iidaka. There was a ceremony and a great banquet. Though alcohol was normally forbidden, the restriction was lifted for the evening and it turned into a night of wild drinking. The students, including Denpachi, drank themselves into a stupor. Denpachi became so drunk that he lost control over his disguise and transformed back into an animal. His deception revealed, the other students descended upon Denpachi. They tied him up and beat him nearly to death. Then they dragged him before Saint Nōke for judgment. Denpachi kneeled before the headmaster with tears in his eyes and begged for forgiveness. Saint Nōke listened to Konoha’s plea. He was touched by the kitsune’s sincerity, his success and diligence as a student, and his passion for helping others. He told the students, “For the teachings of the Lotus Sutra to have reached the heart of this lowly beast, it is truly a marvelous thing!” Saint Nōke forgave Konoha. Konoha promised to serve the temple as a guardian spirit and protector of the faith. Saint Nōke built a small shrine for him in one corner of the lecture hall’s front garden. Eventually Konoha came to be known as Konoha Inari Daimyōjin, a local deity who grants wishes to farmers, merchants, and students. His shrine still stands and remains a popular place of devotion. K T A 経蔵坊 : none; this is his name : Kyōzōbō, hikyaku gitsune (“postman fox”) A : Keizōbō is a kitsune who transformed into a young samurai and served Lord Ikeda Mitsunaka of Tottori Castle as a message runner during the 17th century. B : Keizōbō ran messages from Tottori Castle to Edo. He could make the journey in a record-breaking three days. Keizōbō was beloved by his lord for his talent and dedicated service. Keizōbō is the husband of Otonjorō, another famous kitsune from Tottori. L : Keizōbō was on his way to Edo to deliver an important message from Lord Ikeda. As he ran past a small village, a rich and delicious smell wafted up from the side of the road. A farmer was placing deep fried rats into snares. Keizōbō approached the farmer in the guise of a young samurai and asked him what he was doing. The farmer explained that he was laying traps for the foxes who had been destroying his fields. Keizōbō made a note of it and continued his run. Keizōbō arrived in Edo, delivered his message, then turned around and headed straight back to Tottori. He took the same route back, which took him by the same village he passed earlier. Once again, the mouth-watering aroma of fried rat tickled his nose. The smell was so enticing that even though he knew it was a trap, Keizōbō decided to try to snatch a fried rat. He moved as quickly as he could. But poor Keizōbō was not fast enough. He got caught in the snare and died. When Lord Ikeda heard that Keizōbō had died he was distraught. He had a shrine built on the side of the mountain near his castle, and Keizōbō’s spirit was enshrined there as a guardian deity. The Nakazaka Inari Shrine where Keizōbō is enshrined still stands in Tottori City. O T おとん⼥郎 : Otomi the prostitute A : Otonjorō is a kitsune who haunted the mountain pass of Tachimitōge. Otonjorō is a shortened version of Otomi jorō (Otomi the prostitute)–one of her many transformations. B : Otonjorō excelled at transforming herself and bewitching men crossing the mountains. She was famed for escaping capture over and over. L : One night, a merchant was traveling through Tachimitōge. On the road ahead he spotted a young woman in a kerchief. He thought she must be the wicked Otonjorō out hunting men. The woman called out to the merchant, “Oh merchant! Would you take me to the nearest village and help me find a man to take me as a bride?” The merchant decided to trick her before she could trick him. He would take her to his friend Jūbē’s house and capture her. He put on his best poker face and told her to come with him. The merchant led the woman to Jūbē’s house only to discover it was already decorated in preparation to receive a bride. It was late at night, but Jūbē’s servants welcomed him inside. They treated him with the warmest hospitality. Jūbē’s servants offered him a hot bath, which sounded wonderful to the road-weary merchant. He soaked in the tub for some time, and eventually the sky began to lighten. At dawn, the village’s farmers headed out into the fields. They called out, “Look! That man must have been bewitched by Otonjorō!” The merchant was startled to see they were all pointing at him! He suddenly realized he was sitting naked in a dung pot in the middle of a field, rubbing excrement all over his body. The whole night had been a trick. He became the laughingstock of the village. Another legend tells of a village headman who could no longer contain his anger with Otonjorō’s mischief. He called the villagers together and promised a reward to anyone who could exterminate the kitsune. A pair of braggadocious young men volunteered. The men ventured into the mountains to look for Otonjorō. When they reached Tachimitōge they spied a fox walking along a small river up ahead of them. They watched it rub river mud onto its body and transform into a young woman. She picked up a river stone and it transformed into a baby, which she cradled in her arms. The two men followed her until she entered a small mountain hovel. The men peeked into the hovel and saw an elderly couple cradling the baby. They burst in and told the couple they were bewitched by a kitsune and the baby was a stone. But no matter how much they explained, the old couple would not believe it. They insisted that the baby was their own grandchild. The young men had enough. To prove the baby was a stone, they snatched it out of the elderly couple’s arms and dropped it into a boiling pot. The baby screamed and died. It did not turn back into a rock. The young men were mortified. The couple overpowered them, tied them up, and called for help. A priest passing by heard the cries. He offered to take the two men to his temple where he would ensure they spent the rest of their lives praying for the soul of the dead child. The elderly couple agreed. They turned the young men over to the priest. He shaved their heads and took them to his temple deep in the mountains. Days passed. The two young men did not return home, and the villagers began to worry. They sent a search party. Near Tachimitōge, they discovered the two men sitting in a river, covered in mud. Their heads were shaved, and they were repeatedly hitting a river rock, chanting Buddha’s name. O T 尾無し狐 : the fox with no tail A : Onashi gitsune is an old, white-furred kitsune who haunted the Nagao cape in Aoya, Tottori Prefecture. B : Onashi gitsune was exceedingly cunning. Her preferred modus operandi was to transform into a middle-aged woman and bewitch people crossing the hills. O T 恩志の狐 : the fox from Onji A : Onji no kitsune is a wicked, elderly, brown-furred kitsune who haunted the area between Onji and Iwami in Tottori Prefecture. B : Onji no kitsune loved to trick people traveling in the mountains alone at night. He appeared some distance ahead of them and created a magical light. People would think it was the lantern of another traveler and follow the light. But Onji no kitsune would lead them deeper and deeper into the mountains and then abandon them. S T ショロショロ狐 : a nickname based on the sound of falling water A : Shoroshoro gitsune is a white-furred kitsune who haunted the road between Tanegaike and Shichi Mountain in Tottori Prefecture. B : Shoroshoro gitsune preferred to transform into a beautiful young woman to trick travelers. Her name comes from the “shoroshoro” sound of water falling in the foothills of Shichi Mountain. T I F K The eastern part of Tottori Prefecture was known as Inaba Province in the old days. This small region was home to several famous kitsune, who are known as the Inaba Five Kitsune. They are made up of Keizōbō, his wife Otonjorō, Shoroshoro kitsune, Onashi gitsune, and Onji no kitsune. Each lived in a different village in Inaba, and they show up over and over in the local legends of the region. Like most kitsune, the Inaba Five were fond of deep-fried rats. If you put up a bunch for sale, one of the Inaba Five was sure to come and try to trick you out of one. They transformed leaves into one sen coins and used them to buy the fried rats. If you were a seller, you would try to rip each coin in half before accepting it. If it did not rip, it was a genuine coin. But if it ripped, it was a transformed leaf, and the customer was a kitsune in disguise. O T おさん狐 : Osan the fox A : Osan gitsune is a kitsune from Western Japan. Tales of her mischief are found throughout Ōsaka, Hiroshima, and Tottori Prefectures, and most of the Chūgoku region. Whether these all refer to the same character or different kitsune named Osan is not clear. B : Osan gitsune was stylish and influential. She frequently traveled back and forth between her hometown and Kyōto and received ranks and honors from Fushimi Inari Shrine. I : Osan gitsune transformed into beautiful women to seduce men into betraying their wives and girlfriends. She was so seductive that men young and old would visit her again and again. Some of them even saw through her disguise, yet carried on their romantic flings. Osan gitsune was deeply jealous and vindictive. She was fond of starting lover’s quarrels to break couples up. Women who interfere in others’ relationships–particularly those involved in adulterous affairs–are sometimes called megitsune (fox women). This word is said to have originated from Osan gitsune. O : Osan gitsune is said to have lived near Eba, Hiroshima. She is beloved by the villagers of Eba, who claim her as their own despite her mischief. By the time she was 80 years old, she had given birth to over 500 foxes who lived in the vicinity. During food shortages after World War 2, the locals fed and took care of the city’s foxes. These are said to be Osan gitsune’s descendants. Today, she is memorialized in Eba with a bronze statue, and her spirit is enshrined in a small shrine at Marukoyama Fudōin. L : One of Osan gitsune’s favorite pranks was to disguise herself as a lion and set fire to her tail. In this guise she terrorized people traveling roads at night. One time she was captured by a merchant, who threatened to burn her alive. She begged him to let her go and promised that the following night she would transform into a daimyō’s procession for him–a rare sight indeed! The merchant agreed and released her. As promised, the following night a splendid daimyō’s procession approached the city. The merchant was thoroughly impressed. He approached the procession to praise the kitsune. However, it happened to be a real daimyō’s procession and not a kitsune’s trick. The daimyō was so offended by the merchant’s impudence that he had him beheaded. In Tottori, Osan gitsune lived in a place called Garagara near present-day Tottori City. She appeared to travelers day and night, and often lured them back to her home. One day she attempted to seduce a farmer named Yosobei. Yosobei knew that a kitsune lived in the area, and he was prepared to resist her temptations. When Osan gitsune approached him, he pretended to be seduced and followed her back to her house. There, he burned her with fire. Her disguised faltered and her true form was revealed. Osan gitsune begged for her life. Yosobei agreed to release her if she swore never to do harm again. She agreed and fled the area. Several years later, a man from Tottori encountered a beautiful young woman traveling alone on the roads. She approached him and asked if a man called Yosobei still lived in Tottori. The man told her that yes, Yosobei was alive and well. The woman exclaimed, “Oh god! How terrifying!” and ran away into the woods. O おこん狐 T : Okon the fox A Shizuoka. : Okon gitsune is a kitsune from Jitōgata in Makinohara, B : Okon gitsune was a malicious troublemaker who loved playing tricks on humans who lived near her home. Her signature prank was to attack travelers on the road and shave their heads. L : A fishmonger was carrying his daily catch through the hills when an elegant lady approached him to buy some fish. She was having a party and wanted every single fish he had. The fisherman was delighted. He had never sold his entire catch so quickly before. He happily traded his fish to the woman and went home early. When he told his wife what happened, she became suspicious. There were no families with that kind of money living anywhere near the hills. The fisherman agreed it was strange. He checked his purse. The coins the woman had paid with were gone and in their place was a handful of leaves. He realized he had been tricked by Okon gitsune. The fisherman decided to punish Okon gitsune. He grabbed his staff and went back to the hills. The hour grew late, but he could not find the kitsune anywhere. Then he heard a great commotion coming down the road. A daimyō’s procession was heading straight his way. The soldiers leading the procession ordered him to make way. The fisherman jumped off the road and prostrated himself. The ground rumbled as soldiers, horses, and the daimyo’s palanquin passed. As he bowed, he thought it odd that daimyō would process through this rural stretch of hills. Surely this was Okon gitsune playing another trick on him. This was his chance to catch her! He jumped up and approached the daimyō’s palanquin. As he reached for the palanquin’s door, a booming voice came from within: “INSOLENT PEASANT!” Such an impudent act meant death. The guards seized the fisherman and forced him to the ground. A daimyō stepped out of the palanquin. He drew his sword to cut off the fisherman’s head. The fisherman begged the daimyō to spare his life. The daimyo replied, “I will spare your life, but you will shave your head so all may see your impudence.” The guards held the fisherman down and shaved his head. He groveled in the dirt until the procession left. Everyone in the village would see how foolish he had been. He wrapped his head in a kerchief and sheepishly returned home. When he told his wife what happened, she again became suspicious. There was no way a daimyō would travel through such rural, backwater hills. The procession was clearly another one of Okon gitsune’s tricks. Her husband had been fooled again. But she pointed out that whether it was Okon gitsune or not, if he had remembered his manners, he would still have his hair. K 管狐 T : pipe fox A : izuna H : mountains and forests of central and eastern Japan; or the houses of their owners D : omnivorous A : Kudagitsune are a breed of tiny, thin, magical foxes, about the size of a rat. They can possess and manipulate humans and are usually found in the service of sorcerers and fortune tellers. Because of their diminutive size, they can be conveniently hidden on the body–tucked in a sleeve or pocket or carried inside of a matchbox or a bamboo pipe, from which they get their name. B : Wild kudagitsune behave like other small mammals such as foxes, stoats, and weasels. They keep to themselves and usually remain hidden from humans. Only rarely does a kudagitsune allow itself to be tamed and brought into a human household to serve as a magical familiar. I : Kudagitsune are used by sorcerers in divination rituals and to place curses upon people. They loyally serve an entire family. Families with kudagitsune use them to tell fortunes, make prophecies, and haunt their enemies. Or the enemies of their clients, if the price is right. When directed, kudagitsune cause sickness and ill fortune. As a result, such families are often shunned by their neighbors. Households with kudagitsune are called kuda mochi, kudaya, kuda tsukai, izuna tsukai or kudashō. Kuda mochi families can use their abilities to acquire any riches. They quickly accumulate wealth and power. However, such families can collapse just as swiftly as they rose. Kudagitsune breed quickly. Kuda mochi families can find themselves with seventy-five or more kudagitsune. Having too many kudagitsune brings a family to ruin. The tiny creatures eat them out of house and home. At the same time, culling them to keep their numbers in check risks angering a powerful magical animal. Giving them away to other families carries its own risks. O : Kudagitsune magic originated in the mountains of Nagano Prefecture, but has spread throughout central and eastern Japan. Because of their diverse range, kudagitsune are known by many different regional names. The most famous is izuna, from Mount Iizuna, a mountain with ancient ties to shamanism. O オサキ T : varies depending on the kanji used A : osaki gitsune H : forests and mountains; also found in homes and human bodies D : omnivorous; fond of azuki beans mixed with rice A : Osaki are small, magical mammals with fluffy tails split in two at the end. They resemble weasels, mice, or tiny foxes. Some accounts describe them as a cross between a fox and an owl, a little bit larger than a house mouse. Their fur is mottled and can be brown, grey, red, white, or orange. Their noses are white at the tip. Their ears look like human ears. Some have a black stripe running from nose to tail. B : Osaki are found in Nagano and throughout most of Kantō. In Tokyo, however, they are only found in the Okutama Mountains in the far west of the prefecture. This is because the Ōji Inari Shrine, the head kitsune shrine in Kantō, forbade low-ranking kitsune like osaki from entering the city. Osaki live in the mountains, but also sneak into human homes. They are usually invisible but will show themselves at the sound of a pot lid or a rice container being struck. They are extremely fast and appear and disappear suddenly. They reproduce quickly and form large packs which move like a swarm. Osaki have powerful magic and are often used by the gods as divine messengers. I : Osaki can enter human bodies, especially those who have wronged the osaki or its masters. Victims of osaki possession suffer bad luck and mysterious injuries. They develop fevers, mental and physical agitation, gluttonous appetites, and other eccentricities. Osaki possession can only be cured through exorcism. Villagers are cautioned not to torment wild osaki to avoid provoking their wrath. Osaki are kept by humans as magical servants. If kept happy, they bring great wealth to their owners. Families with osaki are called osaki mochi or osaki tsukai. When an osaki mochi family’s fortunes rise, they overflow with wealth while the fortunes of their neighbors mysteriously decline. Conversely, when an osaki mochi family’s fortunes fail, they plummet into ruin and never recover. Osaki ownership is passed down from generation to generation matrilineally. Great care is taken to keep osaki ownership secret. Osaki mochi families were historically shunned and mistrusted for their unnatural abilities. They withdraw from society and avoid contact with the outside world. Marriage is only permitted with other osaki mochi families. However, marrying into an osaki mochi family makes the other family osaki mochi too. If a bride was discovered to be secretly osaki mochi, trying to marry into a non-osaki mochi family, the wedding would be be called off. Once a family becomes osaki mochi, they are always osaki mochi. No magic ritual can remove osaki from a family line. In a way, the family does not possess the osaki; the osaki possess the family. O : Osaki descend from the nine-tailed kitsune Tamamo no Mae. When she was killed, her body transformed into a great cursed stone. When the stone was shattered by a priest, pieces of it flew through the air and landed in Gunma, where they transformed into the first osaki. Osaki can be written with several different kanji. One way is 尾 先 , meaning “tail tip,” referring to the shattered tips of Tamamo no Mae’s tails. Another way is 尾裂, meaning “split tail,” referring to the osaki’s two tails. Another way is 御先, which comes from the word misaki, referring to animal spirits employed by the gods as messengers. Ō T 王⼦の狐 : the foxes of Ōji A : Ōji Inari Shrine is famous for kitsune folklore. Located in Ōji in Kita City, Tōkyō, it is the head shrine for all kitsune in the Kantō region. B : Every year on New Year’s Eve, the kitsune of eastern Japan gather in Ōji to give thanks and make wishes for the new year. O : Before the 20th century, Ōji was a village of rice paddies and farms. Visiting kitsune gathered under a huge hackberry tree by the road. Magical fires used to light their way could be seen for miles around. Farmers and merchants in Edo would watch for the lights to predict the coming year’s fortunes. Inari is a god of the harvest and business, and many kitsune gathering at the shrine would mean a prosperous year. L : A rakugo story called Ōji no kitsune takes place in Ōji. A merchant returning from a visit to the Ōji Inari Shrine witnessed a kitsune transform into a beautiful woman. He looked around to see who her target would be. He was the only person around. Rather than becoming her target, the merchant decided to turn the tables and play a trick on her. He called out to the woman, “Otama! It’s me! Come, let’s have tea together!” He pointed to a nearby tea shop, Ōgiya. The kitsune thought she had found her mark and played along. They entered the shop and took a seat on the second floor. The merchant let the kitsune order as much as she wanted. Eventually, drunk and full, she fell asleep on the floor. The merchant went downstairs, ordered three dishes of tamagoyaki to go, and then told the shopkeeper that the woman upstairs would cover the bill. He slipped out. A server went upstairs to wake up the sleeping woman and ask her to pay. The kitsune was so shocked that her disguise failed, revealing her tail and ears. The staff chased her around the restaurant. They beat her with a broom. Finally, the kitsune managed to escape. She ran back to her hole in the ground and hid. The shopkeeper asked what all the commotion had been. When the staff told him what happened, he scolded them. “This shop owes its success to the Ōji Inari Shrine. How could you beat one of its kitsune?” Together, they went to the shrine to apologize and pray for forgiveness. Meanwhile, the merchant arrived at his friend’s house. As they shared the tamagoyaki, the merchant told his friend what had happened. His friend looked worried. “Kitsune are vindictive creatures. She will probably place a curse upon your family!” The following day, the merchant returned to Ōji to make amends. Near the place where he saw the kitsune the day before, a cub was playing near a hole in the ground. The merchant apologized to the cub for his behavior and left a wrapped present beside the fox hole as a sign of his contrition. The cub’s mother was inside the hole sulking. The cub told her that a human came by to apologize for tricking her and had left a present. She was skeptical, but let the cub to open the box carefully. It was filled with botamochi–rice cakes covered in brown, mashed sweet beans. “They look delicious mom! Can we eat them?” asked the cub. The kitsune replied, “No. Humans are vindictive creatures. That’s probably horse shit!” A First and foremost, I want to thank my wife for all the unseen effort she put into The Fox’s Wedding. We decided to produce this book as locally as possible, so while I painted in my studio she reached out to local printers to find one who could meet our needs. While I read amusing ghost stories, she contacted remote town halls and cultural centers to request information on obscure local yōkai that I insisted on including. She took care of my health, and she made sure I ate proper meals and slept on time instead of whatever I would have done if she wasn’t around. While The Fox’s Wedding was written, illustrated, put together, and published by me, there are many people whose work is an important part of this book. The beautiful typefaces used are The Fell Types, digitally reproduced by Igino Marini: www.iginomarini.com. The typeface used for Japanese text is Iwata Gyōsho. The illustrations were painted digitally in Clip Studio Paint using the fantastic GrutBrushes by Nicolai: www.grutbrushes.com. The text was edited by Zack Davisson: www.zackdavisson.com. Last but certainly not least, I want to thank my patrons and supporters who helped make this book a reality. That includes the backers who crowdfunded the project on Kickstarter and Backerkit, and those who have supported me for years on Patreon. They make it possible for me to research, translate, and illustrate yōkai full time. Over 5,500 people backed this project, which is so many that I had to move the list of names to the end of the book in order to fit everyone! Thank you all for your support. I hope you’ll continue to read my books in the future! The Fox’s Wedding is dedicated to everyone who helped crowdfund this book, including: A G Urquhart, A joy to help bring this to reality., A Kitsune named Hua Li, A Larger World Studios, A Tomlins, A. Banack, A. G. M. O. Prepok, A. Levi Midcap, A. Speakmon, A. Tipper, A.M. Lopez, A_Square, Aaron & Alyson Sturley, Aaron B., Aaron Bailey, Aaron Finkbeiner, Aaron Hanson, Aaron Morse, Aaron Pothecary, Aaron Rosenberg, Aaron Schindler, Aaron Teiser, Aaron W. Thorne, Aaron Ward, abbi.gitsune, Abbie Jordan, Abel Teo, Abhilash Lal Sarhadi, Abie McCauley, Abital & Daryl, Adam & Looie Krump, Adam Bargmeyer, Adam Benedict Canning, Adam Brousseau, Adam Dahlheim, Adam Everhardt, Adam Fleischer, Adam Gonzalez, Adam Hinrichs, Adam Jacobsen, Adam Johnston-Manley, Adam Kellenberger, Adam Nacov, Adam Normandin, Adam Nusrallah, Adam R Pippin, Adam Rusinak, Adam Signorelli, Adam Vickerman, Adam W. Roy, Adira Yohn, Adrian Hopwood, Adrian Loughman, Adrianne, Adric Waddell, Adrienne Choma, Aelfie, AEQEA, Agustin Angel, Aidan Castle, Aiden Junor, Aileen Kennedy, Aimee Fincher, Aimee Millspaugh, Aisha Laury, AJ and Christina for Henry and Sophia, AJ Etzweiler, AJ Stein, Aje Sakamoto, Akira Kessler, Akisame Sou, D.Johnston, Al Effendi, Al Rusk, Al Welch, Ala Mustafa Mohamed, Alaina, Alaina Grantham, Alan Agostinelli, Alan Brazelton, Alan Burnstine, Alan Loewen, Alana Melnick Haddox, Alasdair Sinton, Albert Lew, Albert Plana Mallorquí, Albertine Feurer-Young, Alberto Faria, Alberto Pérez-Bermejo, Alberto Villa Alvarado, Aleae Warlock, Aleatha, Alejandro Arque Gallardo, Alejandro San Martin Lamas, Aleks Marcetic, Aleksei Limos, Alem Al-Khamiri & Laura Edwards, Alex “MonsterChef” Neilson, Alex Cina-Bernard, Alex Clark, Alex Context, Alex Engel, Alex Fox, Alex Garcia, Alex Iptok Melluso, Alex Kartzoff, Alex Miller, Alex Murff, Alex Parker, Alex Porteous, Alex Schaeffer, Alex Wainwright- ‘Kaiju Curry House’ Podcast, Alex Yates, Alex Youngman, Alexa Landis, Alexander “Llama” Millar, Alexander Aprahamian, Alexander Burns, Alexander Comolli, Alexander Fandos, Alexander G. Cobian, Alexander Grey, Alexander Hughes, Alexander J. Martin, Alexander Kandiloros, Alexander Rennie, Alexander von Schlinke, Alexandra Bell, Alexandra Loaiza-Carrera, Alexandra Tolmie, Alexandra Washick, Alexandra White, Alexandre Moynier, Alexandru C Lepsa, Alexandru Făgădar, Alexia Diogo, Alexis Cicero, Alexis Gordon, Alexis Pettitt, Alexxander Shaw, Alexys Hillman, Alfapeto, Alfredo Reyes, Ali, Ali R. Malek, MD, Ali Walsh, Alia Schamehorn, Alice Fawcett, Alice Marks, Alice Marvaldi, Alice Ridgway, Alice Styczen, Alice Vandommele, Aliké Uwimana Chambers, Alisa Heletka, Alisha Walton, Alisha Yockey, Alison Cundiff, Alison Rognas, Alison Sky Richards, Alissa M Maxwell, Alistair Gilmour, Allan Joseph Medwick, Allen Bartley, Allen Baum, Allen Garvin, Allen Sorensen, Alley Livingston, Alli Tripp, Allison B, Allison Keiko, Allison Meyer, Allison Rittmayer, Allison-Marie Molnaa, AllMicksedUp, Ally “MattsyKun” Bishop, Allyson Russell, Altorl, Alvin KG Yap, Alvin kwa, Alwin Solanky, Aly Wilkins, Alyc Helms, Alysa Kataoka & Anthony Yoon, Alyson Blamey, Alyssa C, Alyssa Лиса Zakaryan, Alyssa Loney, Amalia Paulson, Amand Berry, Amanda “Kez” Astra, Amanda Dunnie, Amanda Gunn, Amanda Hilter, Amanda Kadatz, Amanda Koyumi Igaki-Aribon, Amanda L. Nordstrom, Amanda Lord, Amanda Patterson, Amanda Saville, Amanda T. Corbett, Amanda Watson, Amanda Wee, Amanda Zimmerman, Amandine Rebiffé, Amber East, Amber Galster, Amber Hyde, Amber Malzahn, Ambra Urso, Ambrosia J Webb, Amelia Barcroft, Amelia Koen, Amelia Temperley, Amir Ramsahaye, Ammon T, Amos, Amsel and Bryony Page von Spreckelsen, Amsel Leon Alston, Amy Barker, Amy Brewer, Amy Chatterton, Amy Driedger, Amy Fox, Amy Heather Nguyen, Amy L. Kendall, Amy Makin, Amy Marchant, Amy Smyth, Amy TaylorMitropoulos, Amy Winters-Voss, Amy Yonekawa, An Nguyen, Ana Soto, Anastasia Belodumova, Anca Grigorut, Ander Mendia, Anders Björkelid, Anders Jansson, Anders McCarty, André Le Deist, Andrea Bergner, Andrea Gates, Andrea Johnston, Andrea Kis, Andrea Landaker, Andrea M Bowes, Andrea Rhude, Andrea Romans, Andrea Yarhi, Andreanne Lamothe, Andreas Walters, Andres Renteria, Andrew “Hawkeye” Outram, Andrew & Kelly Blake, Andrew Bartel, Andrew Barton, Andrew Boon, Andrew Bowman, Andrew Choi, Andrew Foxx, Andrew Gershon, Andrew Gonzalez, Andrew H, Andrew Hart, Andrew Kavros & Alexis Kavros, Andrew Kilcup, Andrew Lacroce, Andrew Lang, Andrew Lohmann, Andrew Martin, Andrew Munsey, Andrew Murtland, Andrew Overhiser, Andrew PAppas, Andrew R Nay, Andrew S. Collins, Andrew Schnagl, Andrew Shue, Andrzej Kubera, Andy & Deb Dickinson, Andy Campbell, Andy Linderman, Andy Pearce, Ang Shu Yan Divya, Ang Zuan Kee, Angel Ludw, Ángel Martín Sánchez, Angela Daly-Coleborn, Angela Gunn, Angela Irene C. Feliciano, Angela Mashlan, Angela Mazur, Angela Mondragon, Angela R. Sasser, Angela Thomas, Angelia Pitman, Angelina J.I.Greco, Angelique Blansett, Angelique Gibson, Ania Bartkowiak, AnimalMother NJ, Anjali Shanti Changa, Anka S., Ann Glusker, Ann Kilgore Reay, Anna Alkire, Anna Giulia Compagnoni, Anna Kardby, Anna Lorenc, Anna Turner, Anna Vaughan Papworth, AnnaLynn Molitoris, Anne Brightman, Anne Robertz, Anne Schneider, Anne Snowdon, Anne-Louise Monn, AnneMarie Eriksson, Annette Wilkinson, Annie Will, Ant Jones, Anthony Ames, Anthony Bianchi, Anthony Clark, Anthony Gorczyca, Anthony Greenly, Anthony Perkins, Anthony Plescia, Anthony Rieger, Anthony Thompson, Anthony ‘Tony’ Peace, Antohammer paper miniatures, Anton Vettefyr, Antonia Mitova, Antonio Esteban, Antony Karl Karlytzky/Patrick - NZ, Antti Hallamäki, Antti Luukkonen, Anya Martin, Aoi Scarlet, April Berry, April Collins, April Gutierrez, Aquamarina, AR Takeshita, Aramis Garcia Gonzalez, Arbor Bayda, Archantael, Arec Rain, Ares Alt, Argent Fox, Aria Rei, Arianna & Laurence Shapiro, Arianna Fowler, Ariella Rivka “Wallaby” Weiss, Arigato from Shelley Garner, Arinn Dembo, Arisa Yoshida, Arizona’s Dad, Arjang Taiby, Arlais Sol’amaranth, Arlene Taylor, Arlieth, Arnaud D’haijère, Arnold Petit, Aron Tarbuck, Arron Capone-Langan, Art, Arthur A. Virtue-Stracke, Arthur Brendan Pembrook, Arthur Peregrine White, Arthur Trapp, Artur Derlatka, Arun Sharma, Ash Brown, Ash London Guy, Ash Miller, Asha and Myles Wolfe, Asha Cinnabar, Asha Storm, ashford2ashford, Ashkan T Paykar, Ashleigh Williams, Ashley & Evan Phillips, Ashley Durnall, Ashley Hankins, Ashley Hooper, Ashley M. Orndorff, Ashley Mathews, Ashley Niels, Ashley Soh, Ashley Underdown, Ashley Wilkes, Ashley Y, Ashli T., Ashton “Ashe” Agnes, Ashuri Taka, Asian Geek Squad, Aslam A, Astanex, Athena Austen Grey, Athena Miz, Aubrey Ang, Aubrey Hill, Aubrey Richardson, Audrey Herke, Audrey J Eldridge, Audrey SIMON, Aurélie Leclerc, Aurora Carnes, Aurora Elliott, Aurora Newton, Aurora S. Braig, Aurora Wolfe, Aurore DM, Austin & Kaeley Kunze, Austin C Appleby, Austin de Lumine, Austin Mills, Author Joel Norden, Autumn Beauchesne, Autumn G. Van Kirk, Autumn Kaviak, Autumn Russell’s Dad, Autumn Taylor, Ava Zelver Everett, Avery Bacon, Avry M. Phantong, AwesomeJacketDude, Aythami David Caraballo Arrocha, B Lammey, B R Dutcher, B.A. McLean, BABA, Babette Kraft, Baby Beluga, Backer #5720, BACON Baptiste, Bader Alomar, Bailey Widmer, Barbara Chang / Dedra, Barbara Painter, Barbie Wilson, Barclay T. Hygaard, Barney Menzies, Barokmeca, Barry E Moore, Barry Welling, Bartol van der Wingen, Bartosz V. Bentkowski, Bashar Tabbah, Bat, Bauer Raposo Benjamin, Baygl, BBK & BBK, Bearheart, Bearlycute, Beatrice Bowers, Beatty Sensei, Beauty, Becca Collis, Beck Torrey-Payne, Becki Grady, Becky Lutz, BehemothEmperor, Bekah Ewers, Belladonna Grimm, Bellatrix Aiden, Belle Taylor, BelovedKiki, Ben “Bairhanz” Williams, Ben & Jasmine Moretti, Ben & Ryn Noey-Thacker, Ben and Toni, Ben Clapper, Ben Cook, Ben Craton, Ben Hansen, Ben Haslar, Ben Hoogendoorn, Ben Kaiser, Ben Love, Ben MacCormack, Ben McFarland, Ben Mendelsohn, Ben Piper, Ben Schmoker, Ben Skirth, Ben Stinson, Ben Stones, Ben Trigg, Ben W Bell, Ben Wong, Beni Jenkins and Alexia Wolf, Benita K, Benjamin “BlackLotos” Welke, Benjamin “Zero” Sky, Benjamin Anderson, Benjamin B. Soon, Benjamin Eliasz, Benjamin Galliot, Benjamin Hatherley, Benjamin Hopman, Benjamin Radford, Benjamin Reinhart, Benoit Cecyre, Bernadette P., Berserk Art and Tattoo, Bert, Bertram Vogel, Beth Coll, Beth Zyglowicz, Bethanie Queen of Everything, Bethany Cai Graham, Bethany Einer, Bethany Neff, bethanyARTE, Betsy Aoki, Betsy Hathaway, Bette-Berg, Bianca Rumpp, BigTed, Bill Lewis, Billie Jo Beats, Billy Fox, Billy Tucci, Birdy, Björn Elmlund, BL Choo, BlackMN, Blaine Ross, Blandine Bayoud, Blee Chua, BLewisArts, Blythe & Matthew Hodgin, Bob + Grainne Hoyne, Bob Bouma, Bob Cook, Bob Goolsby, Bob Harrison, Bob Thayer, Bobby Mendenhall, Bobby Swift, Bonnie Ward, Boots McGuire, Boyd Mardis, Brackett-Urata Family, Brad Asari, Brad Gabriel, Brad Roberts, Bradford Stephens, Bradley White, Bram D, Brandi Babilya, Brandi Walsh, Brandon Duke, Brandon Fletcher, Brandon Hall, Brandon James Gabriel Eaglefather Stoltz, Brandon Lawrence, Brandon Lee Allendorf, Brandon Lennox Sheridan-Keller, Brandon Reuter, Brandon S Higa, Brandon Sams, Brandon Shields, Brandon Snyder and Joseph Williams, Brandon Stover, Braxton Galliher, BreAnna Sygit, Breanne Cremean, Brenda A. Sullivan, Brenda Lyons, Brendan Lambourne, Brendan Stork, Brenna Glenn, Brennan Bova, Brent Millard, Brent walker, Brent White, Bret Burks, Bret E Hall Jr, Brett Augustine, Brett Bursey, Brett Rioux, Bri Gonyea, Brian and Archie Hutchison, Brian Auriti, Brian Browne, Brian D. Alexander, Brian Dysart, Brian Edward Karlsson, Brian Gibbs, Brian Isserman, Brian Katchmer, Brian Medrano, Brian Monroe, Brian Patterson, Brian R. Bondurant, Brian Randeau, Brian Sebby, Brian Stuhr, Brian Suskind, Brian Vidovic, Brian Watanabe, Brian Wood, Brianne Bedard, Brice A Campbell, Briceson Tish, Bridget Laing, Bridget McLemore, Brigitte Colbert, Brin Greaner, Britt Leckman, Britta and Will, Brittany Yu, Brittney Cole, Britton Steel, Brock Otterbacher, Bronwen, Brook West, Brooke and Ryan Murray, Brooke Center, Brooxe Lahey, Bruce Strong, Bruno Canato, Bruno Durivage, Bruno Rodríguez Aniorte, Bryan Ezawa, Bryan Lee Davidson-Tirca, Bryan McCormick, Bryan Rosander, Bryan Sorak, Bryan Vestey, Bryce Orion Platt, Brynne A. Williamson-Lawson, Bugbears in San Francisco, Bunny M., C Gascoyne, C&R Locke, C. Coffman, C. Corrado, C. Davidson, C. Harris, C. Holliday, C. Markwood, C.M. “Buzz” Tremblay, C.P.M.Mills., Cade Cochran, Cailyn Toomey, Caitlin and Anthony Cooney, Caitlin Blomgren, Caitlin Hobbs, Caitlin LampeWilson, Caitlin R Kight, Caitlin Raleigh, Caitlin Strigaro, Caitlyn “Koenig” Smith, Caito & Jonah, Maddy & Ben, Cal Lister, Callan Griffiths, Callie Hadley Turney, Cally Steussy, Calvin D. Jim, Calvin Layne, Calvin-Khang Ta, Camella McMillion, Cameron Hamblen, Cameron LaVoy, Cameron Quinzel, Cameron Schaefer, Camille, William and Tim Rhodes, Capri Block Basel, Capy Head, Carina Baranova, Carissa Stevenson, Carissa White, Carl Carlson, Carl D. Rosa II, Carla Baglieri, Carla L., Carla M. Eble, Carlij Sikorski, Carlos E Restrepo, Carlos M Flores, Carlos Ovalle, Carlos Rehaag, Carlos Tkacz, Carlough, Carly and Tony Mace, Carmen Elisabeth Longbottom, Carol, Carol Ann Webb, Carol Austin, Carole Ann Webb, Carolin D., Carolina Alonso & Dylan Adelman, Carolyn Rogers, Carolynn Adderson, Carrie Kei, Carson Bennett, Cary “Frang” Sandvig, Caryn W, Casey Casdorph, Casey Elizabeth Arn, Casey Hanks, Casey, Marshall and Roxy, Cassandra Hansen, Cassidy Tebeau, Cat Leja, Caterina Roversi, Cates Eliasen, CatFish, Cath Evans, Catherine and Belle Fox, Catherine and Peter Christian, Catherine Dobson, Catherine Jordan, Catherine M. Wallace, Cathi Gertz, Cathy Green, catmilk, Cayla and Charles Peter Nystrom, Cecelia Rafferty, Cecilia Billheimer, Cecilia L Shifflett, Ceera Brandt, Ceol Fox, Cesar A. Velez, Cesar Loayza Campos, Chad Briggs, Chad Connelly Jr., Chad J Pocock, Chakrit Yau, Chaosengineer/Aporeia, Chaplain Christopher Mohr, Charise Arter (DNogitsune), Charles E. Hickle, Charles Hons, Charles Kowalski, Charles Makoto Kanavel, Charles Rhodes, Charlie, Charlie Katagiri, Charlie Perich, Charlie R. W. Gottlieb, Charlie Swarbrook, Charlie Taylor, Charlie Williams, Charlotte & Keira, Charlotte Beaudet, Charlotte Claridge, Charlotte Coneybeer, Charlotte K., Charlotte Lindau, Charme Chen, Charon Dunn, Chase Allen Strickland, Chase Rude, Chaz Hardesty, Chee Lup Wan, チェイフィン・レイ チェル, Chelle, Chelle Destefano, Chellygel, Chelsea Kano, Chelsea Kroeker Hebert, Chelsea P.T., Chelsea Sylvanus Aganda, Chelsie Hargrove, Chenhey, Cheryl, Cheryl Bush, Cheryl Fulton, Cheryl Soper Goode, Cheryl Vogel, Cheshire cat, CheshireCatSith, Chi Cornell, Chibi Okamiko, Chicory, Chikane B., Chloe A., Chong Ho Lee, Choong Ngan Lou, Chris “Squeeky” Sullivan, Chris & Tiffany Bowman, Chris and Doug Silvey, Chris and Jacqui Mitchell, Chris Aumiller, Chris Ber, Chris Carney, Chris Conkling, Chris Crowther, Chris Gallivan, Chris Hall, Chris Hartford, Chris Helton, Chris Holgate, Chris Huning, Chris L Rogers, Chris Landon, Chris Lauricella, Chris M. Hughes, Chris McCombs, Chris Mihal, Chris Mobberley, Chris nelso, Chris Okasaki, Chris Ols, Chris Reynolds, Chris Saia, Chris Shaffer, Chris Smith, Chris Spinder, Chris Suzuki, Chris T. Chung, Chris Walker & Hillary Sanborn, Chris Wuchte, Christel Gonzalez, Christian “Effi” Hellinger, Christian Bitz, Christian Claus Wiechmann, Christian Dacres, Christian Douven, Christian Holt, Christian Katsabas, Christian Lange, Christian Phipps, Christian Roese, Christian Sheppard, Christian Yuen, Christina Boyd, Christina Letourneau, Christina M. Hughes, Christina Marie, Christina Pederson, Christina Settingiano, Christine Choquette, Christine Fisher, Christine Gilpin, Christine Goldschmidt, Christine Goodnight, Christine Kern & Dusty Feeney, Christine Lee, Christoffer Nygaard, Christophe Van Rossom, Christopher A. G. Eccleston, Christopher and Meg <3, Christopher Charles, Christopher Cureton, Christopher D. Huelsman, Christopher D. Nichols, Christopher D. Sandford, Christopher DeJong, Christopher Emmanuel Lugo, Christopher Fisher, Christopher Glosson, Christopher Hall, Christopher Hill, Christopher Horn, Christopher Horsfield, Christopher Irvin, Christopher J Mills, Christopher Leslie, Christopher M Gasink, Christopher McKalpain, Christopher McQuillan, Christopher Miranda, Christopher Orr, Christopher P. Thompson, Christopher Redfearn-Murray, Christopher S. Perry, Christopher Stallings, Christopher Stieha, Christopher Tanaka, Christopher Zabawa, ChuChuEn, Chuck Callahan, Chuck Mock, Chuck Oldaker, Chuck Pell, Chuck Wilson, Chuyee Yang, Ciara & Rob, Ciarra Vaughn, Cin, Cindujan R., Cindy Lee Kennedy, Cintia de Carvalho, Cipriano Treviño, CJ Mitchell, Claire Dixon, Claire Higgins, Claire Iverson-Burt, Claire Smales, Clara Balmer, Clare Templey, Clark & Connie Gegler, Claudine, Claudio H P Lins, Clay Gardner, Clayton Freund, Clements Family, Cliff Norris, Cliff Winnig, Clifton Royston, Clint Rose, CM Rice-Howell, Coal The Coward, Cody Jackson, Cody L. Dobbs, Cody Saul, Coeli, Coldsnap Carlo, Colin Beadle, Colin Masterson, Colin Nisbet, Colin Perry, Comanga LLC, Concave Gallery, Conductive Music CIC, London, Conen Slusher, Connie Crum, Connie Fan, Connor Doughty, Connor Lewandosky, Connor McCain, Connor Palmer, Conor Elvidge, Conrad “Tuftears” Wong, Conrad Chuang, Constanza Mestre, Cooper “Niero Oni” Morris, Cooper Clan NY, Cooper Young, Cor Schadler, Corbett French, Corbie Mitleid, Corbin Brown, Cordelia Mortimer-Lee, Corey A Towne, Corey M Modrowski, Corey Sanderson, Cori Bennett, Cori H, Cori Paige, Corinna Bechko, Corrie Wheeler, Coudière Emilie, Court Heller, Courtney Chulsky, Courtney Gallegos, Courtney Lynch, Courtney McDowell, Courtney Menikheim, Courtney Palmer, Courtny Fenrich, CPT Bex, Cpt. Awesome, crackthefiresister, Craig Hackl, Craig S. Weinstein, Craig Smuda, Cremated Survivor, Cristacat, Cristian collado, Cristina Carballa Rosales, Cristina López-Ayala, Cristina Massaccesi, Cristina Soriano, Cristophlyz, Critiana Rayne, Crys Fung, Crystal Eio, Crystal White, CS Jennings, CsipekCzigola Gábor, Curacion Cameron, Curtis Taulbee, Curtis Y. Takahashi, Cyle Kelly, Cyndy Sims Parr, D & J Salter, D Patrick Beckfield, D Ryman, D Stow, D. Bobby E. Fry, D. Hrynczenko, D. Kleymeyer, D. Kloimwieder, D. P. Rider, D.J.Woodruff, D.R.Percell, D.Ron Martin, Dag, Dagmar Wyrmkin, Dai, Daimadoshi, Dakota Garland, Dakota J. George, Dakota Mellin, Dakota Streubel, Dakotah & Alexis Darnell, Dallas Hetrick, Damian & Catherine Lauria, Damian Gordon, Damian Tomczik, Damir Fatušić, Damon Griffin, Damon-Eugene Rich, Dan Grendell, Dan Jeffery, Dan Murray, Dan P, Dan Panda, Dan toth, Dana I., Dana Macalanda, Dana Maley, Dana Miller, Dana Rudnitsky, Dandansama, Dandelion, Danese Cooper, Dangomew, Dani and Thomas Andersen, Dani Arnold, Dani Hoots, Danica B., Daniel Barrett, Daniel Belanger, Daniel Blower, Daniel Choi, Daniel Clark, Daniel Cossai, Daniel Dahlberg, Daniel Drew, Daniel Evans, Daniel Gelon, Daniel J Harle, Daniel J. Tapanes, Daniel Joyce, Daniel Kurokawa, Daniel Markwig, Daniel McLane, Daniel McNeil, DANIEL PHANG, Daniel S. Lovasz, Daniel Stein, Daniel Sundborg, Daniel Thiele, Daniel Truong, Daniela Mendoza-Ruiz, Daniele Micocci (Kayth), Danielle “Dani” Moss, Danielle & Panton, Danielle C., Danielle Inman, Danielle Lombardi, Danita Doun, Danni Zhu, Dannii Laman, Danny Burns & Eric von Paternos, Danny T. Peterman, Danny Thai, Daphné AMERIO, Dara Grey, Darbury Laine, Darby Lifer, Darren Davis, Darren HJA, Darren McDonald, Darren Reed, Darrin Deeks, Darryl Johnson, Darryl Manning, Daryl G Morrissey, Daryl Hrdlicka, Daryl Lawton, das_frunk, Dave Alexander, Dave and Susie Adamson, David “Chtounet” Moreau, David & Bethany Childs, David and Erika Reichert, David Arlt, David Badger, David baity, David Ballard, David Bateman, David Bennett, David C. Chin, David CE, David Chambers, David Chart, David D. Eakin, David Deom, David Drum, David Edelstein, David Field, David Glass, David Glennie, David Griswold, David Hochman, David L. Donaldson, David Laine, David Lars Chamberlain, David Larson, David Lewis, David Magyari, David McDermott, David Millians, David Mitchell Clauson, David Nelson, David Palau, David Pardiac, David Parry, David R W Reynolds, David Ramey, David Ramon Santamarina, David Raposa, David Raynaud, David Robards, David Roberts, David Ruskin, David Saward, David Shi/史 岱 威 , David Stephenson, David Sternau, David Sundin, David Takashi Matsui, David Tiggemann, David Veasey, David W., David Wagner, David Wensky, Davina Tijani, Davis Banta, Dawn Ernster Yamazi, Dawn Oshima, Dawn S DuRall, Dawn Vogel, Dayv ‘THM’ Mitchell, D-dubya, Dean Glanville or Combopuddle, Dean Karalekas, Dean M, Dean Rutter, Deb Fuller, Debbie Marlene Bevers-Malone, Deborah Bonnema Perry, Deborah pettingill, Deborah Spiesz, Deborah V. De Bernardi, Dechlan Brody Stopher, Dee L Neff, Dee Perrault, Deirdre “Dee” Carey, Deirdre Morrison, Della LefflerDonnell, Delphine K. Ontai, Dena Stoner, Denis Ananiev, Denis Kol, Denis McCarthy, Deniz Kalyon, Denley Messerly, Dennis Yone, Dennys Antunish, Derek Betts & Nancy Rekku Betts, Derek Brazzell, Derek Gutrath, Desiree Lynn Cornell, Desmond Linley, Desmond White, Detectives, Devon Tackett, Diana “Foka” G, Diana Ault, Diana D’Émeraude, Diana Evers, Diana Pisani, Dianne Dimabuyo, Dianne Munro, Didi Dwiastuti, Diego Oondayo Garcia, Dillon “Shogun” Darr, Dillon Tome, Dinglehopper, Dino Hicks, Dirthavaren, DJ Winters, Dmitri B., Dmitrijus Chocenka, Dmitry Martov, Dom, Domanic Torrella, Domenic Merendino, Domenica Campanella, Dominick Cancilla, Dominik Gassen, Dominik Harris, Dominique O. Heffley, Don Prentiss, Don Tornberg, Donald Yasuo Sekimura, Donell Clauser, Donna A. Leahey, Donna Hutt Stapfer Bell, Donna Minar, Dorian Sanabria, Doug and Crystal Robinson, Doug Kidwell, Douglas Candano, Douglas Kolbicz, Douglas Thamm, Dr JoSa, Dr Katya V Shkurkin, Dr Paul Dale, Dr Tom Mansfield, Dr. Brian Nell, Dr. Chris Yeary, Dr. Erin M. Miracle, DVM, Dr. García, Dr. Joy Trujillo, Dr. Kirstyn Humni, Dr. Meghan L. Dorsett, Dr. Nick, Dr. Robert Hannigan, Dr. Susan B. Livingston, Dr. Unken, Dragan Stanojević - Nevidljivi, Draven Fiori, Drew (Andrew) South, Duncan, Duncan Lenox, Blaine Lenox and Jason Lenox, Duncan Westley Armstrong, Durval Pires, Dustin Ahonen, Dustin Casselberry, Dusty Higgins, Dyan Arnold, Dyl Cook, Dylan “Caligula” Distasio, Dylan Dalton, Dylan Metz, Dylan Myers, Dylan O, Dylan Schrader, Dynax, E & N Fowler, E. Francis Kohler, E.L. Winberry, E.X.B, Eco, Ed Freedman, Ed Mccutchan, Ed Romson, Edbert Fernando Widjaja, Edbury Raymond Enegren IV, Eddie Hobart, Eddie Joo, Edison Patiño Mazo, Edmund McIntosh, Edna Gamez, Edouard PERIN, EDUARDO VG AND KARLA MZ, Edward Chavers, Edward M. Aycock, Edward MacGregor, Edward Paul Dombrowski, Edward Stalker, Edwin Tjhin, Effandy, Egg, Ehedei Guzmán Quesada and Tatiana Alejandra de Castro Pérez, Ehenn, Eileen Holmes, Eilein, Eilidh, Eirene S. Hobbs, El Wood, Elaine M. Cassell, Elaine Maulucci, Eldrich Solmeyer, Eleanor Asher, Eleanor Munro, Elena Malamed, Elena Maureen Martinez, Elena T. Barnes, Eleonora Witzky, Eli Eaton, Eli Hamada McIlveen, Elia F., Elias Iraheta, Elisa M. Cimons RN, Elisa Townsh, Elisabeth D. Loijens, Elisabeth Hegerat, Elisabeth Oos, Elise Hart, Elisha Hamilton, Eliska Svarna, Eliza Woodrow, Elizabeth “Betz” Stump, Elizabeth and Paul, Elizabeth Armetta, Elizabeth Charlotte Grant, Elizabeth Cope, Elizabeth Davis of Dead Fish Books, Elizabeth Fox, Elizabeth Grace Williams, Elizabeth Gray, Elizabeth Lathrop, Elizabeth Payne, Elizabeth Swanser, Ella & Archie Fennell, Ella Foxglove, Ellen Adamson, Ellen Emerich Hart, Ellen Jane Keenan, Ellen Jokela Måsbäck, Ellen Kimura Eades, Ellie Beck, Ellie Gerrard, Elliot Cuskelly, Elliott Sawyer, Ellis, Ellis Putman, Ellixis, Elly Gausden, Elmo Dean, Elsa Marcel, Elwin Maglanque, Elysa Gray-Saito, Em Barnhill, Em Hodder, Em Jakse, Emanuele Vicentini, Ember Bridgford, Emerald L King, Emerson Rodríguez A, Emi V Tomijima, Emilie Smarr, Emily Bass, Emily Brander, Emily Coulter, Emily Ebertz, Emily Edmonds, Emily Lawrence, Emily Nelsen, Emily Pardoe-Billings, Emily Rivas, Emily Saidel, Emily Saito, Emily Talukdar, Emily Tilbury, Emily-Alice Wolf, emjrabbitwolf, Emma Brooke-Davidson, Emma Castleberry, Emma Dixon, Emma Holden Axiö, Emma Holohan, Emma Iles, Emma Laeser, Emma O’Brien, Emma Osborne, Emma Roberts, Emma Swann, Emma, Peter, Gabriella and Emilia Rossi, Emmanuel M Arriaga, Emmanuelle, Emmet and Jesse Golden-Marx, Emmet Kalish, Emmy Yamaguchi, Emo, Ender Kukul, Enjoy!, Enna Aedan Holmes, Envol Movement, Eoin Murray, Eoin Ryan, Epredator, Epros Weiss, Eri Feralova, Eric “Jinx” Bergman, Eric Ebbs, Eric Greenberg, Eric H Krieger, Eric J Wells, Eric keog, Eric L Richardson, Eric Lethe, Eric Mauer, Eric McCommon, Eric McLachlan, Eric O. Costello, Eric R., Eric Schulzetenberg, Eric Scott Petrucelli, Eric Steinbrenner, Eric T. Manchester, Eric Z. Willman, Eric Zawrotny, Eric, Samantha and Asher Deans, Erica, Erica “Vulpinfox” Schmitt, Erica Staab, Erick Reilly, Erik, Erik & Anna Meyer, Erik Archambault, erik norman berglund, Erik Peterson, Erik White, Erikku Arashi, Erin A Sayers, Erin Hyatt, Erin K. Parker, Erin Keuter Laughlin, Erin Lindell, Erin Lowe, Erin McCoy, Erin Palette, Erin Sara, Erin Shoemate, Erin Valenciano, Erin Voss, Erin York, Erin Yucel, Ernesson Chua-Chiaco, Ernie Moreno, Ernie W Cooper, Erykah Van, Eryn J. Dahlstedt, Eryn Lowenstein, Esben H., Estella Zorn, Estelle Franklin Holmberg, Estelle Lee, Esther Myers, Esther Phillips, Esther Weyer, Ethan Paul Campbell, Ethan Wilk, Ethan, Dorthy & Momo, Ether, EUGENE PLAWIUK, Eunice C., Eva Jade Cooper, Eva S., Evan Detlefs, Evan Digney, Evan M. Salce, Evan Pellnitz, Evan Zajdel, Eve Renee Greer, Evelyn Thompson, Evi Roberts, Evie Vincent, Ewen Cluney, F E O L T, F. Meilleur, F.R. McNeil, Fabian Brügel, Fabian Liessmann, Fabien Fernandez, Fabrice Chappuis, Faerrin Spann, Fahad Rashid, Faith Barnett, Falconette Foughx, Familia Pezzoli Figueroa, Fco Javier Aparicio Ferrer, Fearlessleader, felicia katz-harris, Felipe Carvallo, Felipe Kl, Felix A Barron Munoz, Felix F. Dossmann, Felix Stulken, Fennec Foxfire, Ferllando Setiawan, Ferret, ferry, Fil Tarjanyi, Filip Källman, Filiz Karahasan, Finn Darby, Finnley and Ronan Kury, Fiona Hampton, Fiona Holderbach, Fiona Wilson, Fionnbharr Remington, Fitzi, Flindt, Flora Bui Quang Da, Florence Forr, Florence L. S. Trahair, Florian Ubr, FoDeJo, FoolishImmoralFOOL, For Frank from Matt, for J.D. Stark, Forest Rogers, Forrest B. Fleming, Forrest Long, Fox and Bear, Fox Bloomberg, Fox Keif Gwinn, Fox Magrathea Circe, Fox Spirit Design, foxes.mn, Fran Messina, Frances Caddick, Frances McGregor, Frances Rodgers, Francesc Quilis, Francesca Richardson, Francisco Ferrer, Franck Gaudillat, François Labelle, Frank Acevedo, Frank Kergil, Frank Loose, Franki Kaye, Frankie Negron, Franklin Shea, Franklin Thijs, Fred Herman, Fred Moreau, Fred Springer, Freda Drake, PhD, Freddie & Christine Hirtzel, Freddie Kaplan, Frederick Ostrander, Fredrik Holmqvist, Freya M, Freya Ross, Freyja Khione Andersdottir, Fritz Sands, Frog, G, G, G Oxford & F Douthwaite, G R sheppard, GA Kozak, Gabe Young, Gabriel and Laura Thompson, Gabriel Bartholomew, Gabriel Golden, Gabriel Vieira, Gabriella Andrietta, Gabrielle Blaug, Gabrielle Menard, Gabrielle Sample, Gabrielle Walsh, Gaea DillD’Ascoli, Gaël Marchand, Gail de Vos, Gail M, Galen Skibyak, Gareth Davies, Gareth Dean, Gareth Maurice Poole, Garett Langer, Garrett Simpson, Garrick & Amanda Peterson, Garrick Dietze, Garrick Mason Wright, Gary Gaines, Gary Motyczka, Gary Phillips, Gary Rumain, Gayle Keresey, Gayle Yeomans, GC Lim, Gemma Denise, Gemma Palmer, Genesys Creed, Genevieve Cogman, Genevieve Martin, Genevieve Packer, Geneviève Vanier, Genni Stewart, Geo Holms, Geof Baum, Geoff Webb, geoff wrenn, GeoffM, Geoffrey D. Wessel, Geoffrey Schumann, George B. Schramm III, George CamilePerkins, George Clarke, George Deane, George Guzman, George Petty, George Reissig, George T. Kaparos, George VanMeter, Georgia Boyden, Georgia Freedman, Georgia Lillie, Georgina Ballantine, Gerald Smith, Gerhard Fertl, German R. Sanchez, Gerrit Deike, GhostCat, Ghyslain Hallé, Gian Pablo Villamil, Gianni Inzitari, Gigi Levens, Gigi Lin, Gilberto Prujansky, Gilles Poitras & Steven Farnum, Gina Collia, Gingy, Gino Luurssen, Glen Livesay, Glenn, Glenn & Reese, Glenn Adrian, Glenn Curtis, Glenn Strouhal, GMarkC, Goatframe, Gold, Goose, Gordhan Rajani, Gordon Garb, Gordon Sutherland, Grace Spengler, Gracelin Chan, Grady Fox, Graham Huffman, Graham Powers, Graham Steed, Granny, Grant B., Grant Harrell, Grant Kidwell, Grant Voakes, Grant William Ball, Grayraven, Grayson Culwell, Greg “schmegs” Schwartz, Greg Cobb, Greg Sheehan, Gregoire Monteil, Gregory Pearson, Gregory Romano, Gregory Teitelbaum, Gretchen Schroeder, Grey, Griz, Gropfanger, Groviglio Prinz, Guilherme Bouzan, Guillaume Ash, Guillaume Pv, Guillermo Sánchez Estrada, Gunnar Peter Holt, Guy Goodwin, Guy Hagg, Gwenn R, Gwenno Talfryn, Gwyn FatMon, H. B. Flyte, H. Michalek, H. Serotta, Haggai Kovacs, Hal Motley, @hamildong, Hamm, Hana Nin, Handon Black, Hannah Brown, Hannah Cleaveley, Hannah Lawther, Hannah Rei Joy Sanderson, Hannah S-J, Hannah Tharp, kitsune of the weird, Hannah VanWyck, Hannes Schulz, Hans D. Metaxenios, Hans Holm, Hareillustrations, Harper Behling, Harpreet Singh, Harriet Rankin, Harsh Thakar, Harvey Jesús López May, は す の は (hasunoha) @lotus_happa, Hastur, Hayley Deeken, Hayley E. Smith, Hayley G. Hofmar-Gle, Hayley L Morgan, Hazardous, Hazelyn Aquino, Heath Flor, Heath Hoxsie, Heather Allen, Heather Blanchard, Heather Crawford, Heather Kern, Heather Lee Ward, Heather Meyer Bradley, Heather Pierce, Heather Securo, Heather Spry, Heather St. Clair, Heather Trussell, Heather Whitman Carroll, Heather Winston, Hector Lopez, Heidi Aussie, Heidi Bottjer, Heike Fleischmann, Heinz Eder, Helen and Kate, Helen Febrie, Helen Gracie, Henning Colsman-Freyberger, Henrik “Hambone” Schmidt, Henrik Dahlström, Henry & Emily, Henry Ashtreemoss, Henry Kuah, Henry Tufts, Henry Z, Hester Kenneison, Hillary Harris Moldova, 東風森子, 悲 劇 の 大 名 , Hillel Cooperman, Himelda Pablo, Hiokie, Hirofumi Oyamada, Hitomi Meyer, Hollis Handel, Holly Kingham, Holly Mitchell, Holly Pelton, Holly Richards, Holly Y Conklin, Holly Young, HonOtoko, Hope Sabanpan-Yu, Horace Robison, Horus, Hrayr Tumasyan, Humphrey “Duif” Clerx, Hung Ken Chan, I backed this, I. Mennings, I. Thompson, Iain Murphy, Ian Bray, Ian Cheng, Ian Connor, Ian Elliott, Ian Goulet, Ian H., Ian K Ono, Ian Osborn, Ian Quinn, Ian S Scharrer, Ian S. Moroni, Ian Van Mater, Ian Vinten, Ian Yeager, Ignacio J Ceja, Ignis Matthews, Ike Scott H., Iliad, Iliana Simmons, Ilja Isphording, Ilona and Gordon Andrews, ImaginaryDreams, Imran Inayat, Imredave, In honor of Lia Kimiko, Ina Alexandria Gur, Inês Esteves, Inga Wyss-Delapena, Ingmar Weltin, Inktail Nekogami, Instagram Razanrip, Invader horizongreen, Ioannis Cleary, Irene, Irene Wibawa, Iria Sokoll, Irina Monk, Irina Warren, Iris Powell, Iris Sancho, Ironheart Artisans, Isabella and Verity Koxvold, Isabella Cocilovo-Kozzi, Isadora Raven, Ishan, Isit Doom Muenster Lady, Isla Dail, Isolde and Michael Schneider, Itoshiko & Toshiro Neko, Iván Contreras, Ivan LoTo, Ivan Philippovsky, Ivy Wui, I-Wei Feng, @iwritemonsters, Izzy B, Izzy Carr, Izzy Watts, J Darden-Jackson, J J Ezra, J. Asher Henry, J. Butchart, J. H. Schroeder, J. Jasper, J+K, J9 Vaughn, Jaci F., Jack Mitchell (KOI, IISS detached service), Jack p waite, Jackie G., Jackie Heezen, Jackie King, Jackie Moller, Jackie Winston, Jackson and Kai, Jacob Collins, Jacob Franklin, Jacob Goldstein, Jacob Lewis, Jacob M Gaudette, Jacob Minick, Jacob Rice, Jacob Saina, Jacob Smith, Jacob Smith, Jacque Howell, Jacqueline Hazen, Jacqueline Holler, Jacqueline M Hanchar, Jacqueline S. Beaulac, Jacqueline Skelton, Jacquelyn Reel, Jade Anderson, Jade Groves, Jade K, Jade Kukula and Ricky McKee, Jade M, Jade R, Jade Slocombe, Jaide Helton, Jaime De la Torre Torres, Jaime Hernandez, Jake Bamford, Jake Linton, Jake Wade-Stueckle, Jake William Smith, Jakob Frederiksen, Jakob Thomsen, Jakub Šén, Jalea Ward, Jameka Haggins, James, James, James “MysticFox” Cole, James & Amber Miller, James Alex Hogshead, James and Galia DeThomas, James and Julia Ford, James Birdsall, James Buckley, James Carr, James Conover II, James Coppard, James D Bail, James Dalton, James DiBenedetto, James H. Durborow II, James Harvey, James Hildebrandt, James J Delmark, James M. Dunn, James McGee, James N Psathas, James Preston, James R. Byerly, James Rapien, James Rose, James Thorpe, James Toulmin, James W. Keller, James White, James Wu, James-Henry Holland, Jamie Buckland, Jamie Butler, Jamie Cannon, Jamie Holl, Jamie Lawson, Jamie Merz, Jamie Norman, Jamie Pellerin, Jamien Yeoh, Jamila Hulbert Kepple, Jaminx, Jan Svihra, Jane Ellen, Jane Lawson, Jane Rayson, Janel Carr, Janell Sorensen, Janet Lehr, Janet T. O’Keefe, Janice Campbell, Janis Hirohama, Jan-Moritz Hatje, Jannis Radeleff, Japanime Games, Jarcy de Azevedo Junior, Jared lachmann, Jared Munsterman, Jasmine Benson, Jason & Lisa Mounteer, Jason Brick, Jason Buchanan, Jason Buell, Jason Duke, Jason Folkers, Jason Fox Cohee, Jason Gould, Jason Hunt, Jason Hurd, Jason King, Jason Leisemann, Jason Lindo, Jason Nomura, Jason Scheirer, Jason Schindler, Jason Silzer, Jason Tomlinson, Jason Washburn, Jason, Parker, Norrin, and Tristan Wong. The Yokkai fans!, Jasper Belle Will, Jasper Wang, Jateshi Jigoku, Jating Chen, Jaume Barallat, Javi & Pilipi, Jay Kominek, Jay Lyon, Jay V Schindler, JaYKub KolTun, Jazmin Collins, JC and Sarah Voskaya, Jeanne Edna Thelwell, Jeannette Will, Jeff and Sarah, Jeff Barnes, Jeff Gruhlke, Jeff Hartley, Jeff Lewis, Jeff Matsuya, Jeff Muse, Jeff Nath, Jeff Weber, Jefferson Svengsouk, Jeffery Wright, JEFFREY D SHERMAN, Jeffrey J Glenn, Jeffrey Osthoff, Jeffrey Park, Jeffrey Sauer, Jeffrey Scott, Jeffrey Welker, Jelena Milasinovic, Jemal Hutson, Jen P “Yoko”, Jen Strangeways, Jenjen4280, Jenn Diec, Jenn L. Jones, Jenn Moss, Jenna L Skeen, Jenna Love, Jenna Tulls, Jenni Juvonen, Jennie Crabtree, Jennie Falconer, Jennie Faries, Jennie Ocken, Jennifer A. Graham, Jennifer A. Ludwig, Jennifer A. Ross, Jennifer Beeson, Jennifer Brooks, Jennifer Carr, Jennifer E. Fenster, Jennifer Fincher-Beard, Jennifer G Tifft, Jennifer H. Williams, Jennifer Hejtmánková, Jennifer Hilmoe, Jennifer Joseph Hernandez, Jennifer Koca, Jennifer Lano, Jennifer Lopez, Jennifer Martin, Jennifer Teal, Jennifer V. Zee, Jennifer Vick, Jennifer Whatley, Jennifer Williams, Jennifer, Michael and CyKo, Jenny Hall, Jenny Starr, Jens Cramer, Jeremiah & Sunni Denton, Jeremiah Wopschall, Jeremy Christopher Morgan, Jeremy Diamond, Jeremy Girard, Jeremy Hunter, Jeremy Jacobs, Jeremy Kent, Jeremy Midwinter, Jeremy Pass, Jeremy Robichaud, Jeremy Suizo, Jericho Rath Velus, Jern Ern Chuah, Jerry Reed, Jess Bailey, Jess Taylor, Jess Thorp, Jesse Conn, Jesse Drenters, Jesse Irwin, Jesse McGatha, Jesse N. Hirschmann, Jessi Adrignola, Jessi Moths, Jessica “HawlSera” Nichols-Vernon, Jessica Dai, Jessica F Bradshaw, Jessica Faber, Jessica Gerken, Jessica Hate, Jessica Johnson, Jessica Leeman, Jessica Poll, Jessica Richardson, Jessica Sartore, Jessica Till, Jessica W., Jessica Wong, Jessie Reno, Jesspaul Nibber, Jesús Asvalia Sánchez López, Jethroh Mackenzie, Jetson, Jewel Clarke, Jhermaine & Ronald DeMayo, Jill & Rafe Yedwab, Jill Mitchell, Jim Bennett, Jim Catel, Jim Cox, Jim Demonakos, Jim Genzano, Jim Simpson, Jim Wolf, Jimmy “JR” Tyner 3rd, Jimmy A. Clay, Jin Hun Kim, Jo “Viqsi” Valentine-Cooper, Jo Robson, Joan Leslie Hernandez, Joan Sundt, Joanie Brosas, Joanna McPherson, Joanne Bernardi, Joanne Frankland, Joao Antonio Sarno Bomfim, Jocelyn C., Jocelyn Emerson, Jocy Caldera, Jodee Bucknole, Jodie Ellison, Joe Chapman, Joe Field, Joe Green, Joe McReynolds, Joe Menth, Joe Morgan, Joe Morris, Joe Napolitano, Joe Presley, Joel Archer, Joel Cannon, Joel Kreissman, Joel Simon jr, Joelle, Joey Cote, @JoeyGeeWhiz, Joey Weiser, Johan Eggink, Johann Jimenez, Johanna Mead, Johanna Norton, Johanna Ungeheuer, John & Samantha Harbison, John & Stephanie Bedford, John A. Callahan, John Averette, John B Dilts, John Broglia, John Budreski, John C, John Caboche, John Carberry, John Chambers, John Cook, John E Martin, John F. Brownell IV, John G Blake, John Gotobed, John H. Isles, John Hannan, John Hodge, John J. DiGilio, John Jennison, John Kasab, John Koontz, John Lawter, John Luckini, John M. Atkinson, John M. Portley, John Madigan, John McCloy, John McLean, John Morgan, John Ng, John O’Hagan, PsyD., John P Nguyen, John P. Racine, John Pramuan, John Pula, John R McShane, John Ridge, John Roelker, John Siegel, John Spies, John Still, John Tréinfhir, John V Willshire, John Waterworth, John Wesker, John William Bass, John わ か る か や Krah, Johnathan Byerly, Johnathan L Scanlon, Johnathon Shisler, Johnny Willems, Johnson Thurston, Jolyon Reese, Jon (WEKM) Krupp, Jon Messenger, Jon Phat Trinh, Jon Slater, Jonah Harmsen, Jonathan Cabildo, Jonathan CappIsaksen, Jonathan Ellerker, Jonathan Feeney, Jonathan K. Whitehouse, Jonathan Knell, Jonathan Lambert, Jonathan Lee, Jonathan Lin, Jonathan Louis Allen, Jonathan P. Smith, Jonathan Ross, Jonathan Rust, Jonathan Speed March, Jonathan Young, Jonathon Dyer, Joonas Kilpeläinen, Jordan Champion, Jordan H, Jordan Marchese, Jordan Parker, Jordan Santa Maria, Jordan Silver, Jordan Trygstad, Jordan W. Booth, Jorden Vorachak, Jordyn Schaeffer, Jörg Bennert, Jorge A. Perez, Jorge Antonio Amador Balderas, Jorge Quirós Marín, Jörgen Bengtsson, Jørgen Holand, Jose Angel Gonzalez Sr., José B. Velez Ortega, Jose L Ortiz, Jose Luis Equiza, Joseph A. Noll, Joseph B. Cunningham, Joseph Cotton, Joseph Everett Willis, Joseph F. Jaskierny, Joseph Farnes, Joseph J.J. Santi, Joseph Lenox, Joseph Moses, Joseph P. Elacqua, Josh Farley, Josh Gretz, Josh Howard, Josh Kopin 4 Emily Higgs, Josh Miller, Josh Pattison, Josh S. Talley, Josh Sobek, Josh Storey, Josh Zakerski, Josh Zuchowski, Joshera, Joshua Claussen, Joshua Collier, Joshua Empson, Joshua Furr, Joshua G Corsa, Joshua Kudo Newell, Joshua Landman, Joshua Leonard-Wirfs, Joshua Loui, Joshua Maestas, Joshua Ropiequet, Joshua Smith, Joshua Spencer, Joshua Sunderland, Jovan Humphrey, Jovan Koviljac, Joy Auburn, Joy Cerqueira, Joyce and Greg Chinn, Joyce Hazlerig, Joyce Mihara Boss, Jozef Kools, jp partida-newell, JP Petriello, jr. forasteros, jskc-CJC, Juan Caparas, Juan G. Oquendo, Jude Piper, JUDIKA ILLES, Judit Debreczeni, JUG, Jukka Raskinen, Jules M. B., Juli, Julia Alexandra Pőcze, Julia and Richard Anderson, Julia Horowit, Julia Koper, Julia Rosenlund, Julian Gluck, Juliann of Kintsugi Style, Julianna Ohl, Julie & Joseph, Julie and Clint Overton, Julie Johannessen, Julie Ransom Bullock, Julie Sprague, Juliet Marillier, Juliette Almira-Bohic, Juliette Hall, Julio Luna, June Chase, Juniper Skidmore, Jushin Stephyn Butcher, Jussi【勇士】 Myllyluoma, Just.SoManyCups, Justin Alvey, Justin Biolo, Justin Boese, Justin Caskey, Justin Hudgins, Justin McGeachy, Justin Redmond, Justin Thorpe, Justin Tidwell-Davis, Justin Wilson, Justin Wolfson, Justin Wood, Justine Dumais, Justine Travis, Justis, JW McMullin, K Arsenault Rivera, K P McKenna, K. G. Fenech, K. Kohl, K. R. Sluterbeck, K. Rousseau, K.D. Brogdon, K.F.E, K.J. Brule, Kachenka9, Kae “Skin and Canvas” Hutchens, Kai, Kai Okami Nova, Kai Yu, Kaiden Mollenkof, Kaileigh Robbins, Kairen Si, Kairin Simo, Kaitlin Logan, Kaitlin Thorsen, Kaitlyn Kalmas, Kaitlyn Mason, Kaizen, Kajaanan Mahendrarajah, Kaj-khan Hrynczenko, Kalum from The Rolistes, Kamiki, Kamimakuna, Kamiyu910, Kane Leal, Kara Dischinger, Kara Manning, Kara Nelson, Kara Shostr, Karatails, Karemah Coakley, Karen A. Wagner, Karen Brown, Karen Gemin, Karen Joan Kohoutek, Karen Kocik, Karen Lauzau, Karen Lytle Sumpter, Karen Orange, Karen Pabilonia, Karen Tan, Karen Zieman, Kari Hager, Karjan Amahel, Karl Ziellenbach, Karla Steffen, Karly VK, Karo Skibińska, Karra L, Kasidy Devlin, Kat & Aleric Vancil, Kat Andrews, Kat Cutright, Kat Englin, Kat Forrester, Kat Lovegrove, Kat Schempp, Kat Weinstein, Katarina Kientzle, Katarzyna Kubok, Katelyn Mason, Katelynn Cameron, Katerina Schuh, Katherine A. Winter, Katherine Barton, Katherine Isham, Katherine Kitt, Katherine Sunderland, Katherine Tombs, Katherine Yen, Kathleen David, Kathleen Leavis-Daoust, Kathleen Yu, Kathryn Dusell, Kathryn Eichholz, Kathryn Fenning, Kathryn Mulvaney, Kathy Fork, Katie Armstrong, Katie Beeman, Katie Bridges, Katie D. Coleman, Katie Dresel, Katie Huber, Katie Hynes, Katie Lohman, Katie Monk, Katie Moser, Katie Rayburn, Katie Ritter, Katja Petrovic, Katrina G. Figgett, Katrina Hennessy, Katrinka Mann, Katy Mastrocola, Kavita Manohar-Maharaj & Navin Ramkissoon, Kay James, Kay Miller (GaijinHistorian), Kay Nettle, Kay Watson, Kayla Albarado, Kayla Kolean, Kayla Marrie Odell, Kayla Martin, Kayla Theil, Kaylin Alexandra Tjebben, Kaysey, Kaytee Sumida, Kazeem Omisore, KC Straub, Keeyoni, Keir Alekseii, Keith Bacon, Keith E. Hartman, Keith Haus, Keith Robinson, Keith Smith, Kelila Chai, Kelley Greene, Kellie Crook, Kelly Gilb, Kelly Huitson, Kelly Lavelle, Kelly Phillips, Kelly Stanawa, Kellye M. Fares, Kelman Edwards, Ken Berg, Ken Hamada, Ken ‘Kilroy’ Reinertson, Ken Lovingood, Ken Rusiska, Kendra S., Kendric Bohannon, Keng Yew Choong, Kenned Doll, Kenneth Hadley, Kenneth Ma, Kenny Clem, Kenny Ho, Kent D Taylor, Kent Jenkins, Keri Thwaites, Keriann Gilson, Kerl-of-Fox-County, Kerry L. Huyghe, Kerry Stubbs, Kersti Myers, Kevin & Kati Owen, Kevin A. Daignault, Kevin A. Hildreth, Kevin A. Mitchell, Kevin B. Doyle, Kevin Behring, Kevin Bella, Kevin Brown, Kevin Chapman, Kevin Chung, Kevin Duong, Kevin Hopkins, Kevin Khong, Kevin ‘KT’ Thomas, Kevin O’Brien, Kevin S., Kevin Searle, Kevin Steinbach, Kevin Uhl, Khalid M. Rumjahn Jr., Khloe Sorensen, Kia Dunn, Kid Chameleon, Kieran Dean, Kieran Easter, Kieran Kittral, Kiersten Eckstrom, Kiki Valdani, Kim Andrews, Kim Brown, Kim Cheek, Kim Dyer, Kim M Yates, Kimber Johnson, Kimberly Burkard, Kimberly Fortier, Kimberly Foster, Kimberly Gilson, Kimberly Graham, Kimberly Larouche, Kimberly Simon, Kimberly Wesley, Kimcheebee, Kimera Ongaku, Kimmy Abildgaard, Kimseng, King rat, Kip Corr, Kip Umbreon, Kira Disén, Kira Graham, Kira Ordabajeva, Kirill Lokshin, Kirk A. Silas, Kirsten Bird, Kirsten Rasmussen, Kirstie Stanford, Kirsty M Steele, Kishikawa Masashi, Kit Baker, Kit Fox, Kit Steele, Kit William, Kitalpha Hart, Kitsune Heart, Kitsune Rei, Kitsune_117, Kitteh and Taigrr, Kitty, Kitty Freitag, Kitty Maer, Kiwi Rachar, Kiyoshi D. Igawa, Kizei, KJ Johanson, Klakken, Koh YiShan, Koji Cory, Kou.T, Kovar Fa, Kramer, Krastor, Kris & Ella & Helena Wauters, Kris Austen Radcliffe, Kriska Daltonhurst, Kristan Bullett, Kristen Armstrong, Kristen Volden, Kristen Wood, Kristian Handberg, Kristian Jansen Jaech, Kristian Zirnsak, Kristie Parker, Kristin Rudy, Kristina Gelzinyte, Kristjan Wager, Kristoff Schubilske, Kristopher and Kenya Zarns, Kristopher Bauer, Kristopher Ollie Bingham Scarlett Arroya Weides, Kristy Eighteen, KRL, Krystyn Ng, Krzysztof Nawratek, KT Wagner, Kumoh58, Kurt Johansen, Kurt Piersol, Kurt Zauer, Kwai Lam, Kwinten Deneckere, Kylan Kaneshiro, Kyle Duncan McInnes, Kyle Hall, Kyle Highful, Kyle I, Kyle K. Courtney, Kyle Kowalchuk, Kyle McLauchlan, Kyle Morgan, Kyle Rose, Kyle S., Kyle Schichler, Kyle Sourinho, Kyle Spiegel, Kyle von Schmacht, Kyler St. Clair, Kyllein McKelleran, L Panzarella, L. B. Collin, L. Ethan Cruze, L.A. Schweitzer, L.Schneider, L.Talis, Lady Katherine Ann King, Laekh Traumen, Lana Cooper, Lana Riordan, Lance Esgard, Lance Farrell, Lance Hosaka, Lance Van Meer, Landon King, Lanvrik, Lara Guidon, Lara Miyazaki, Larry and Colleen Beason, Larry Lonsby Jr, Lars I. Nielsen, Laura, Laura Boylan, Laura Burns, Laura Denham, Laura Feeney, Laura Hughes, Laura Jackson, Laura K. Deal, Laura M. Dobson, Laura Mainguy, Laura Mustain, Laura P. Gambel, Laura Packer, Laura Pittaluga, Laura Smith, Laura Stacey, Laura Zapata M.-B., Laure Woolverton, Laurel Shelley-Reuss, Lauren Anderson-Welsh, Lauren Carmack, Lauren Cremona, lauren e ball, Lauren McCauley-Moore, Lauren Merchant, Lauren Noelle Schmidt, Lauren Skidmore, Lauren Takaoka, Laurence Dallas, Laurenn McCubbin, Laurens Van Lint, Laurent De Buyst, Laurie Rollins, Lawjick, Lawrence David Hooper, Lawrence Denes, Lawrence M. Schoen, Lawrence R. Spivack, Lea Kaiaokamalie, Leah Bennett, Leah Warren, Lee Barnes, Lee C, Lee Facey, Lee Gurley, Lee J. LoBello, Lee-Sean Huang, Legend Henderson, Leib Morga, Leighton Elaha Rachael, Lelandra Undomiel, Lene Pagsuguiron, Leo Hourvitz, Leonard & Ann Marie Wilson, Leonora Addams, Leron Culbreath, Leske, Lesley Henderson, Leslie Anne Rogers, Leslie Muldoon, Leslie R. Chaffin, letoze, Levi Mason, Levi Miller, Lewis Hardie, Lex and Leah, Lexi Danielson-Francois, Lex-Man, LexParkJae Ferrer, Liam Brown, Liam Edward Marek Wilson, Liam tunmore, Liberty Lugo, Lien Lintermans, Lila T. Forro, Lili Kurotsuki, Lilia Schmidt, Liliana L, Lilith Rathbun, Lilith Wasmundt, Lilitu Babalon, Lilla Dent, Lilly Cromwell, Lilly Ibelo, Lily & Dara Barkhordar, Lily Chen, Lily-Rose Kihlstrom, LIM EN LING ALEXIS, Lin Clements, Lincoln, Owen & Emmett Peer, Linda “Druttercup” Evans, Linda A. Dominguez, Linda Griffiths, Linda Lombardi, Linda Rothenburger, Lindsay C. Garcia, Lindsay Inskeep, Lindsay Kippur, Lindsay Robinson, Lindsay Schroeder, Lindsay Slessor, Lindsey A Bordwell, Lindsey Goodwin, Lindsey McGowen, Linn Ahlbom, Linn Mobley, Linnea Nilsson, Linzi Keogh, Lionel & Heidi English, Lipton Family, Liry Priel, Lisa Deutsch Harrigan, Lisa Fields Clark, Lisa Homstad, Lisa Jones-Butts, Lisa K, Lisa Martincik, Lisa Nowinski, Lisa S., Lisa Trujillo-Galluzzo, Lise Morrow, LITTLE CROW D. GREENCROW, LittleYokaiGirl, Liz C, Liz Howard, LiZz Beltz and Michael Marra, Lizzy R, Logan Kennedy, Logan W. Faulkner, Lois Santiago, Loki Kruger, London Shine, Lone Phantom, Lord Bob, Loredana Lupu, Loren Eason, Lorenzo “Frank” Zappa, Loreto Collao, Loretta Widen, Lorraine Kidd, Loscro, LOTTA FREDRIKSSON, Lou Colwell, Louis Bodnia Andersen, Louis Chmielewski, Louis-Andre Pelletier, Louise Velma Jones, Love4 Lakas Shimizu, Lucas Luu, Lucas Potter, Lucas Young, Lucia Koonings, Lucia Soltis, Lucianne and Cara Heald, Lucile Barras, Lucy Fry, Lucy Mackley, Luigi Puzo, Luis Alberto de Seixas Buttes, Luis Alfonso Ramos Mena, Luisa Tong, Luisa V, LuisFe, Lukas F, Lukas Pennington, Łukasz Mętrak, Lukasz Nosek, Luke “Nuk3m” Williams, Luke Blair, Luke Kilmartin, Luke W., Lume, Luna, Lura Kaplan, Luzern Tan, Lyana A. Rodriguez, Lyani La Santa, Lydia Hayward, Lydia Savage, Lynette Deley, Lynn C. Li, Lynn Rosskamp, Lynne Whitehorn, Lyon Ramsey, Lyz King, LZJ, M Oehlert, M R Reece, M. “Yarnmonger” Colson, M. A. LaMothe, M. Carey, M. I. Osiecki, M. Inkmann, M. Miller, M. Tischhauser, M.C. Wong, Ma Kuro, Mace Berman, Maciej Cabaj, Mackenzie Sholtz, Maddy Laloli, Madelene Landry, Madeline Bernard, Madeline Wiltse, Madeline Zamoyski, Madison and Shingo, MadRubicante, Maecenas, Maeghan Stewart, Magan Reynard, Magdalena Peterswald, Maggie Birmelin, Maggie Katz, Maggie Keenan, Maggie Young, Magnus Black, Magnus Blystad, Magnus G Rönnb, Maia D., Maisie Battagler, Maite Balado, Mallory Caudron, malpertuis, Mandalay Wohlschlaeger, MANDEM, Mando Ramirez, Mandroo, Mandy B, Mandy Bartok, Mandy Marks, Manuel Avendano, Maralice Roy, Marc Poirier, Marc-André Thibeault, Marcel Wilhelm, Marcella Phelps, Marcelo Will, Marci Muti, Marcia Franklin, Marco Rosenberg, Marcos Nogas, Marcus Zonis, Marcy J. Bridges, Marden, Mare Matthews, Maré W., Marek Barcz, Marek Maryl Pospíšil, Marek Rozenberg-Holszanski, Marek Vincenc, Margaret Cza, Margret Wood, Margrethe Ravn, Marguerite Barnett, Marguerite DeLong, Maria Alldred, Maria Connor, Maria DeRosa, Maria Holland, Maria Johnson, Maria Kathryn Campolongo, Maria Khayutina, Maria Thieme, Mariah Bowline, Maricel Flores, Marie, Marie & Rutger Hill, Marie A. Ranney, Marie Aubry, Marie Barraillier, Marie Brennan, Marie Terskikh, Mariel Keli, Marina Smith, Marion Siegwald, Mariposa H Hernandez, Marisa Gray, Marissa Doyle, Marissa Owens, Mark “Ropey” Crosson, Mark and Jonna Kitsune, Mark and Kirsten, Mark Bradley, Mark C. Turner, Mark Cleary, Mark Cowper, Mark Dines, Mark Disp, Mark Esmann Bang, Mark Flemmich, Mark Glass, Mark Harrison, Mark Junichi Furuya, Mark Kettelkamp, Mark Koppany, Mark L Odom, Mark Laird, Mark Noone, Mark O’Toole, Mark Paul Petrick, Mark Sable, Mark smith, Mark Soenksen, Mark Solino, Mark Yamaguma, Markos Koffas, Marla Hellings, Marlene mcc, Marlowe House, Marsayus, MarshKaleido, Martha E Champion, Martha E. Winston, Martha Juncher, Martha Silver, Martin Glassborow, Martin J. Hoag, Martin Korn, Martin Schwarzmeier, Martin Stein & Scott Saxon, Martis, Martyn Bland, Martyn Wood, Mary Alyssa Reynolds, Mary and James Kendell, Mary Axtmann, Mary DuBoulay, Mary Jirsa, Mary Kennard, Mary L’Etoile, Mary M. Medlin, Mary McVaugh, Mary Nalasco, Mary Nunez, Mary Oliver, Mary Prince, Mary Remmel Wohlleb, Mary T Haynes, Maryanne Snell, Marybeth C. Bishop, Marybeth Thomas Tawfik, Marzie Kaifer, Masahiko Teranishi, Mason Ridgway, Mason Rose, Massimo Maniscalco, Mateusz Wojtas, Mathew Wajda, Mathieu Duval, Matt Allen, Matt Devine, Matt Hajcukiewicz, Matt Jansen, Matt Lichtenwalner, Matt Morgan, Matt Murphy, Matt P Mc, Matt Skibinski, Matt Wallis, Matthew & Crystal Tamura, Matthew A Dang, Matthew Aczel, Matthew Arnold, Matthew B Ander, Matthew Banning, Matthew Bluhm, Matthew C. George, Matthew Carey, Matthew Chang, Matthew Coates, Matthew Delanty, Matthew Dive, Matthew Eroskey, Matthew Gutermuth, Matthew Hill, Matthew Hood, Matthew Ian Stanford, Matthew J Coisman, Matthew Jones, Matthew M.K. Nguyen, Matthew Mack, Matthew Nelson, Matthew Pemble, Matthew Ross, Matthew Schwarz, Matthew ‘Senjak’ Goldman, Matthew Stephen C, Matthew Stolten, Matthew T Miller, Matthew T Scibilia, Matthew Tobias Woodle, Matthew Tompkins, Mattman Lof, Maureen M, Maureen Whitman, Mauro Ghibaudo, Max Dawson, Max Kaehn, Max P J Hollowday, Max Potts, Max Romero, Maximilian Johannes Schug, Maximilian Luu Tran, MaximilianH, Maxwell Bretl, Maxwell Guerrero, Maxwell Stevenson, Maxwell Yeager, maxx ramos, May B., Maybeline P., McKenzie Collins, McLane Dearing Mares, Meaghann Dynes, MeatyBits, Meds Medina, Meera “the Fierce”, Meg Pelliccio, Megan A. Smith, Megan and Joshua Jones, Megan Donart, Megan Elizabeth Moon, Megan Fisher, Megan Goode, Megan M Lalla-Hamblin, Megan-Rose Carnahan, Meghan Fashjian, Meghan Perry, Mel Colburn, Mel W, Melanie Rasch, Melanie Stark, Melgarh, Melinda Gatto, Melinda Shoop, Melinda Woodring, Melissa A. Williamson, Melissa Bucholz, Melissa Finkenbiner, Melissa Lundblad, Melissa Peters, MSc., Melissa Richmond, Melissa Smith, Melissa Tumbach, Melissa Y. Hamasaki, Melody Aimée, Melody Momo, Melri Nightwind, Meng Li, Mer Bishop and Rob Davis, Meredith and Brandon Jeffers, Merlin McGraw, Merri Cash, Merrill Harbour, Merrin Dekens-True, Mévyx, MHW Hill, Mia and Midnight, Mia Lima, Mia Lovatt, Mia SakuraiSpenny, Michael “Esker” Burborough, Michael “Gaijin Goombah” Sundman, Michael “Necro Monkey” Schultz, Michael & Charlene Dobashi, Michael A. Marunchak, Michael and Nicole Bettis, Michael Ball, Michael Barreda, Michael Charboneau, Michael D. Sanders, Michael Dalili, Michael Dzanko, Michael Ehli, Michael Elton Crye, Michael Estergren, Michael Fairall, Michael Ferriter, Michael Foertsch, Michael Francis Adams, Michael G. Bare, Michael Glick, Michael Harrington, Michael Hasslacher, Michael Jarrell Young, Michael Krzak, Michael Logan, Michael Lucero, Michael Mallon, Michael Melahn and Pam Parisi, Michael Meltzer, Michael Miley, Michael Mooney, Michael Nagara, Michael Niederman, Michael Pearl, Michael Penick, Michael Prunella, Michael R. Smith, Michael Ramsey, Michael Scott Brandon (Brandoloneous), Michael Studman, Michael Surbrook, Michael Thompson, Michael Tolzmann, Michael Trevors, Michael White, Michael Whoole, Michael Wolfgang Taft, Michael Woo, Michael Yeh, Michael Zettler, Michaela Knall, Michail Dim. Drakomathioulakis, Michal Valvoda, Michele Howe, Michele Paroli, Michelle Chowning, Michelle Garza, Michelle Goldsmith, Michelle Jones, Michelle Loftus, Michelle M. Pessoa, Michelle Moody, Michelle Osterfeld Li, Michelle Poirier, Michelle Schwengler, Michelle T., Michelle Thaller, Michelle Vucko, Michelle Wei, Mick Scott, Midori Hirtzel-Church, Mighty, Miguel Hundelt & Elizabeth HundeltAnderson, Mika Koykka, Mike (KirstGrafx) Lee, Mike Armour, Mike Barmo, Mike James, Mike Jermann, Mike Kennedy (kylethoreau), Mike Kortness, Mike Martin, Mike O, Mike Peterson, Mike Ratliff, Mike Schnebelen, mike slobodnik, Mike Snowdon, Mikel Cañadas Tanco, Mikey, Mikhail S. Rekun, Miki, Miki Hawkins, Miki White, Miko, Miles L, Millie Tansill, Min Taylor, Ming-Hua Kao, minionseah, Minna, Minny Tusa, @Mipha_pup, Mira Mäenpää, Miranda A. Suarez, Miranda Gast, Miranda Hoop, Mireya Graff, Miri Mogilevsky, Mish Liddle, Miss Denture Thief, Miss Klown, Miss Mochi, Mister Fishie, Misty and Kristy Puckett, Misty Brogan, Mitchel Barry, Mitchell Baker, Miyoshi, Mizore Loves Company, MMALP uit Delft, Moisés Bardera, Molly Francese, Molly Harrison, Molly Phillips, Molly Storm, Monica S., Monika Nowacka, Monte Cook Games, LLC, Monte M. Workman, MoonMoon, Morgan and Jon, Morgan Benson, Morgan Copeland, Morgan David Adams, Morgan Garvin, Morgan Meyer, Morgan. G, moriquenda, Morrigan von der Goltz, Morrison R. Nolan, Moses Lee B.B, Mossy Robinson, mowseler, Mr. Anthony M. Franklin, Mr. Sticky Pants, Ms. Annie Nohn, Ms. Becky Lani, Mychan & WeasleJo, Myki Tsuchiyama, Myokei Caine-Barrett, Myranda Sarro, Myszka and Misiu, N. Pham, Nabil Maynard, Nadine Wester, Nadirah Glanton, namohage, Nancy Edwards, Nancy Oda, Nancy Petru, Nanija, Naomi Asakura, Nara Asihwardji, Narin Leelaporn, Narrelle M Harris, Nat Benefer, Natalia Zmyslowska, Natalie Aoife O’Callahan, Natalie ‘Baba Yaga’ Schneider, Natalie Hasell, Natalie Silberman Wainwright, Natalie Zeller, Natalya Escoe, Nataša v. Kopp, Natasha Erickson, Natasha Nachazel, Natasha R Chis, Natasha Schexnayder, Natasya Pawanteh, Natasza Szulc, Nate Carter, Nathalie and Niels De Bisschop Vandezande, Nathalie Kovacs & Roy Ceustermans, Nathan Anderson, Nathan Clissold, Nathan Evans, Nathan F, Nathan Ganley, Nathan Hasz, Nathan John Haylett, Nathan Manosin, Nathan Mitchell, Nathan Painter, Nathan Rawlins, Nathan W Clark, Nathanael Sumrall, Nathanial Glover, Nathaniel Berneman, Nathaniel Diaz, Nathaniel Hernandez-Botma, Nathaniel J. Hockabout, Nathaniel J. Miller, Nathaniel Nodine, Nathaniel T, Nathaniel Wu, Natthew L., Nayu Shrestha, Neal Hill, Neala Schleuning, Nehemias Llerena, Neikun Rhei, Neil Coles, Neil Dickie, Neil Graham, Neil O’Brien, Neil Ratna, Nell Morningstar Ubbelohde, Nelle Stahl, NEMETHIL, Nervous Charmeleon, Newton Lilavois, NexumiTribe, Nic Dorman, Nicco Marcus, Nicholas and Carol Efstathiou, Nicholas Clough, Nicholas Edwards, Nicholas Genger-Boeldt, Nicholas Jaross, Nicholas Sweeney, Nick & Sarah Teodosio, Nick Chaimov, Nick Herold, Nick Sanders, Nick Suen, Nick T, Nick Terry, Nickawanna Shaw, Nickie Buckner, Nickki Lee Hill, Nickle, Nicky Crewe, Nicla Folla, Niclaz X. Jensen, Nico Vega, Nicola Osborne, Nicolas Burget, Nicole “Thornwolf” Dornsife, Nicole Fraser, Nicole Gawron, Nicole Hodson, Nicole James, Nicole Lindroos, Nicole Locklear, Nicole M. Babb, Nicole Neitzke, Nicole Teixeira, Nicole Whittington, Nicole Winkelmann & John Navarra & Laura Haxer, Nicolette Oathout, Nigel Deakin, Nigel King, Nigel Williams, NightEyes DaySpring, Nightsky, Niki Coppola, Nikki White, Niklas Axelsson, Nikolai Wisekal, Nina Alycia, Nina Kattwinkel, Nina Linger, Nina Pries, Nina Silver Ch., Nityananda M. Woodert, NJ Glassford, Noah Crawford, Noah El Alami, Noah Freeze, Noah Kutaka, Noah Levine, Noah Posthuma, Noel Cotten-Rowland, Noelle McMillin, Noelle Salwocki, Noona, Nora Noodle, Norbert Preining, Nuka-Lola, Nyssa Rodriguez, Nyssa Walker, Nyxx Grey, O.E. Knight, Oesteria, Ofer Fox, OgreM, Ohio Kimono, Olga Diem, Oliver Bogler, Olivia Erickson, Olivia Maria x J, Olivia Noel Long, Olivia Rule, Olivier Lejade, Omer Levy, omkondo, Omri Kimchi Feldhorn, Ondřej Olšanský, OneeNyan, Oriana Dunn, Orlaith McGrath, Oscar Garth, Oscar O’Neill-Pugh, Otis Valentine Hills, Otter Wolterink Hwang, Otterax Avalanche, OtterSilver, Owen Ing, Owen Michaël Peeters, Owen T Myers, Ozzy Barbosa, P, P. J. Reed, Pablo A Rodriguez, Paddy FInn, Paige Kimble, Paige Ozma Ashmore, Painless James, Pakawadee Vanapruk, Pamela J Garver, Pamela Phillips, Pamela Turner, Pan, Pāras Padania, Parelmoer Reijnders, Parker Mc, Parker Peters, Pascal Fischbach, Pascal Picavet, Patricia Tomli, Patrick BadgerPurcill, Patrick Curry, Patrick Dougherty, Patrick Downey, Patrick H., Patrick Herring, Patrick J Vaz, Patrick Jorgensen, Patrick Magisson, Patrick Padua, Patrick Wehner, Patrick ‘Winterfuchs’ Fittkau, Patrik Spånning Westerlund, Patryk Lewandowski, Patti Flynn, Patti Poblete, Paul “oyuki1311” Reynolds, Paul & Erik Schaffner, Paul & Laura Trinies, Paul Baptist, Paul Butler, Paul C. Defenbaugh, Paul Clark, Paul de Haan, Paul Evans, Paul F, Paul Gardiner, Paul Halbmayr, Paul J Hodgeson, Paul Morris, Paul Naseman, Paul Rigby, Paul Rose Jr., Paul Rossi, paul russell, Paul T Smith, Paul Thorgrimson, an old Buddhist crab, Paul Wagner, Paul Was, Paul Wolfe, Paul Zimmer, Paula and Phil PS, Paula O’Keefe, Pauline Martyn, Pauline Ts’o, Pauline Williamson, Pawel Daruk, PecYog, Pedro Ziviani, Peggy Delaney, Penn Family, Per Stalby, Perratone F., PERRY RULE, Persephone Digby Caesar, Pete McNally, Pete Tracy, Peter Boylan, Peter D Kelly, Peter Dyreborg, Peter E. Kim, Peter E. Midford, Peter J.S. Franks, Peter Joelson, Peter ‘Malkira’ Lennox, Peter Marier, Peter Prince, Peter W. Owens, Péter Werner, Petr Drahokoupil, Petr Hrehorovsky, Petra Vašendová, Petrov Neutrino, Petter Wäss, Phil Le Poulpe, Philip Hale, Philip Lazenby, Philip Montgomery, Philip W Nielsen, Philip W Rogers Jr, Philip Wiles, Philippe “Gunsō” Sergerie, Philippe Hintzen, Philippe Niederkorn, Phill Zitt, Phillip G. Massie, Phoenix Fae, Pier Francesco Donzelli, Pierce Ohlemacher, Pierre Mooser, Pingo, Piper Hernandez, Pippin Fisher Reed, Pitchayapol, Piya, Christina and Elliott Wannachaiwong, PJ Mayhair, PJ Nielson, Plunder, Pomegranate Muse & Jordan Hill, Pompilous Baleolus, Pope Winston, Portuga, Pragati Rana, Preceptor_Teeth, Preechaphol Choosri, Prescott Paulin, Presi, Presley Patterson, Protagonist Gaming, Pugsley, Punny cat, Purple Parfait, Py Lowrey, q leedham, Qaantar, Qristanay Shockley Harris, Queen Auset, Queen Ynci, Quentin Christensen, Quentin Foster, Quentin Humphrey, Quentin K. Anederson, Quigley Finch, Quinn Hansen, Quinn Kybartas, Qwon, R. Brian “Antlers” Scott, R. Brookes McKenzie, R. M. Young, R. Paul Steffens, R. W. Pauly, R.A. Fedde, R.J. Crash, R.J. Peloso Jr., R.S. Kennedy, Rabbit Stoddard, rachaar, Rachael Busher, Rachael Hixon, Rachael Lane, Rachel & Peter Carr, Rachel Ann Harding, Rachel Arrighi, Rachel Ashby, Rachel Borchers, Rachel Bussan, Rachel E. Robinson, Rachel Engle, Rachel Grange, Rachel Platt, Rachel Smith, Rachel Syrett, Rachel Szewczyk, Rachel Warble, Rachel Wood, Rachel Yeager, Rachelle, Rae Glitter, Rae Podrebarac, Raenna Caguioa, Rafe Lafornara, Rafi Rodr, Ragan Black, Rai Swanson, Raid Bugshan, Raina Wilcox, Rainbow, Ralph S. Hoefelmeyer, Ramona Lara, Randall Nichols, Raven and Derin Howlett, Raven Ikaera, Ray “VampyriKitty” Zhao, Raye Johnsen, Raymond Fujioka, Raymond Kloss, Raymond Tobias, Raymond Zapata, raymond.zhang, RC Ackerman, Re Knoxville, Reba Hickman, Rebeca Isabel Tellado, Rebecca, Rebecca Allen, Rebecca F., Rebecca L A Milne, Rebecca Lefebvre, Rebecca Lydia Lim Peace, Rebecca McDermeit, Rebecca McManamy, Rebecca Mutton, Rebecca Rauschenberger, Rebecca Rhodes, Rebecca Stoltz, Rebecca Switzer, Rebecca Tapley, Rebecca Tighe, Rebecca White, Rebecca Woolford, Rebecca Wright, Rebekah Conard, Rebekah McArthur, Red, RedJack23, Rednappingcat, redsixwing, Reggie “Shadow” Mare, Regina April Head, Regnant, Rei and Erica Rothberg, Reinier Perez Quinones, Reiumi, Rémi Létourneaw, Remy & Charlie, Ren Greenwood, Renata Aguiar, René Rusin, Renée Blaché, Reorg Raginwulf, Rev. Alicia M Aihara, Rev. Phillip Malerich, Reverance Pavane, Rez Alvarez, RF Percy, Rhett Yelverton, Rhonda S Denney, Rhyta Vyn Helkyreed, Ric Cheeks, Ric Wagner, Ricardo de Goes Correia, Ricardo José Pereira, Ricc Bonifacio, Riccardo “Musta” Caverni, Riccardo Sartori, Rich Barringer, Rich Lafferty and Candice Eisner, Rich Mottern, Rich Olcott, Rich Street, Richard, Richard Aldridge, Richard Banks, Richard Boykin, Richard Dufault, Richard J Hanson, Richard Jones, Richard Kemp, Richard L. de Campo, Richard Loh, Richard Milton, Richard Paul Glass, Richard T. Chandler, Richard Thomas Smith, Richardson, Rick Cicchelli, Rick Duangsawat, Rick LaRue, Rigby Wade, Righan Meehan, Riley Hagan, Rin Tsubaki, Riprope22, Ri-Qing Hu & Ebere Nwankwor, Rita Barrueto, Rita Lepine, Rob Auten, Rob Crowther, Rob Geist, Rob Geyer, Rob Roy Habaradas, Robbie Morgan, Robert McGann, Robert “ ジ ル ク ス - さ ん ” Peterson, Robert and Penny Rubow, Robert B. Tharp, Robert Baldridge, Robert Bowers, Robert Costelloe, Robert D. Seto, Robert DeBroeck, Robert E Lee Spilman V, Robert E. C. Aguilar, Robert E. Stutts, Robert Falconi, Robert Farley, Robert Golias, Robert H. Hudson Jr., Robert Hopkins-Knight, Robert J Duncan IV, Robert Lee Mayers, Robert M. Zaccano, Robert Musser, Robert Waldbauer, Robert Wynn, Robert Zimmermann, Roberto Mendieta, Roberto Sanchez, Robin Ellis, Robin G, Robin Li, Robin Meyer, Robyn Shipton, Rocio Almodovar, Rod Meek, Roderick Nagashima, Roger & Aaron, Roger Kristian Jones, Roger Lewin, Rogin, Roland Hornung, Romikus, Rommy Cortez-Driks, Romy Meyerson, Ron & Melody Hyatt, Ron Hatton, Ronald Le, Ronald Madplume, Ronan & Freya’s Wagon Tales, Rondo, Ronin Gaijin, Ronyo Faukx, Rory DeVore, Rory, Alex and Ravenna King, Rosa Story, RosarioPatric Mullen, Rosbolt Home for Wayward Youth, Rose Brown, Rose Luna Hillock, Roselia Aybar, Rosemary Callahan-Gray, Rosemary Taylor, roserose, Rosie C., Roslind Sanders, Ross MacTaggart, Rosslyn C Roach, Rowan Del Bosque, Rowan McComas, Roxana Samson, Royal Sapp, RPardoe, Rubiee Tallyn Hayes, RUBY O’HARE, Rudy Quin, Rune Bartlett, Russell B, Russell Karbach, Russell Peake, Rusty Katt, Rusty wald, Ruth and Matt, Ruth AshtonWard, Ruth Johnson, Ruth Stephens, Ry and Denise Moore, Ryan A. Campbell, Ryan Brent, Ryan Carr, Ryan D.G. Stout, Ryan Foster, Ryan Hatcher, Ryan Hertel, Ryan Holden, Ryan Jason Wyatt, Ryan McWilliams, Ryan Ogi, Ryan T. Johnston, Ryan Timothy Brown, Ryan W Roberts, Ryan W. Cahill, Ryan Webb, Ryan Worthington, RyanCrow, Ryan-James Cotton, Ryland H Garnett, Ryon Levitt, S Kasari, S. Moon, S. O’Neill, S.Gibbs, S.K. Buck, S.L. King, SaasideA, Sabina Kneisly, Sabrina C, Sabrina Ceslok, Sabrina Rau, Sadaf Seher Ahmed, Sadie Harmon, Sadie McFarlane, SaeYoung Lee, Sairah M. Cathcart, Salem Hanson, Sally Ward, SallyC, Sam and Alex Rosen, Sam Butler, Sam Hakoyama, Sam Houston, Sam Kalensky, Sam Kimelman, Sam Peters ( サ ム ), Sam Sheppeard-Boros, Sam Whittingham, Sam Wright, Samantha Alleman Moreau, Samantha Ashe, Samantha Flora Grace Hamilton, Samantha Ghormley, Samantha Michaelson, Samantha Mosher, Samantha Pitkin, Samantha Scheel, Sami Thomas, Sammii Lea, Sammy Lee, Sampson Family, Samuel Capadano, Samuel Foster, Samuel Singleton, Samuel W J Derbyshire, Samuel.R, Samuli Teerilahti, Sandy Barkeloo, Santiago Moreno, Santiago Russell, SaphDragon, Sara Bergstresser, Sara Elettra Zaia, Sara Heiderscheidt, Sara Kay, Sara Kleiman, Sara Ogden, Sara Perrott, Sara Rantschler, Sara Wrann, Sarah, Sarah A Lustgarten, Sarah A. Graybill, Sarah Bradshaw, Sarah Burns, Sarah Cooke, Sarah Coombs, Sarah DeLacey, Sarah Dicus, Sarah Elizabeth Carlin, Sarah Ellender, Sarah Evely, Sarah F McGinley, Sarah Fay Haarmann, Sarah Fennell, Sarah Gibson, Sarah Hoggan DVM, Sarah Jo M. Wolters, Sarah Klase Richardson, Sarah Liberman, Sarah Lifton, Sarah M., Sarah MacIntosh, Sarah Malyndriel Rial, Sarah Nicole Leichty, Sarah Pelzner, Sarah Richards, Sarah Rose, Sarah Shelnutt, Sarah Swanson, Sarah Teigler, Sarah Underwood, Sarah Wingo-Story, Sarai Porretta, Sara-Marie Hartwig, Saskia Nishimura, Sata and Cat Prescott, Satia Schutz, Savan Gupta, Savana Bell, Saverio Mori, Savonna Stender-Bondesson, Saya and Sabine E., Saya Gehrke, Sayaka, Sayaka Yajima, Scanner, Scarlet Wyvern, Schroeder Family (NJ), Schuyler Goodwin, Scott & Kate Moseley, Scott Anecito, Scott Bachmann, Scott Brazelton, Scott Burns, Scott Carlisle, Scott Crisostomo, Scott Harrison, Scott Hughes, Scott Joseph Jamieson, Scott Knauer, Scott Mahar, Scott McKie, Scott Monsour, Scott Moreland Jr, Scott Morrison, Scott R Bier, Scott Ragon, Scott Raun, Scott Simonini, Scott Thomas Miller, Scott Waites, Scott Walker, Scott Weingartner, Scott Wiggins, Lena Fan and Claudia Wiggins, Seamus A. Smith, Sean & Ryan Clay, Sean Callinan, Sean CeltiBear O’Leary, Sean D. Latasa, Sean Holland, Sean Humphrey, Sean K.I.W./Kelly Renee Steele, Sean Kent, Sean McAffee, Sean Mikles, Sean Pelkey, Sean Robbins, Sean Saile, Sean Sullivan, Sean Walsh, Sean.diz, Sebastian Deusser, Sebastian Larsson, Seet Siew Ling, Seeta Ghowry, Seimei, Sekieigitsune, Selina Tang, SEM, Sendie Prevereau, Seniya Joy Schluter, Seraphina Malizia, Seren Massey, Serena Bozzi, Serena R, Serenity Kaysdatter, Sergey Koptev, Seth Atwater Jr, Seth J. Wiener, Seth Kadath, Seth Rowley, Seth Sollenberger, Seth Urbina, Shafay Sajjad, Shalane Armstrong, Shaleezah Tajvidi & Caelan Maxon, Shana, Shane A. Young, Shane M Tysk, Shanendoah Darrow, Shaney Orrowe, Shannon M., Shannon McClennanTaylor, Shannon Pack, Shannon Rae Mathers, Shannon Spurlock, Shaquille Worthy, Sharon Acosta, Sharon Dolabaille, Sharon M. Fetter, Sharon Mellby, Sharon Reschka, Sharon Yu, Sharré Bakker, Shaula, Shaun Gilroy, Shaun Kelley, Shaun Sains, Shaun Tan, Shaun Thomas, Shawn Beard, Shawn Berg, Shawn C. Rowlands, Shawn Rose, Shawna Jacques, Shayna Kohan, Shayna MacLarty, Shea B.-Turner, Shea Rajala O’Donnell Root, Sheela Caraway, Sheena Ashby, Sheila & Tracy Mazur, Shelby Calvert, Shelley Sue, Sheri Grumbling, Sherri A. Williams, Sherrie Welch, Sherry Liu, Sherry Mock, Shervyn, Shiho Koumura, Shiloh Carlson, Shilpa Nair, Shin-ichiro Taguchi, Shirah Pollock, SHR, ShunnedOwl, Si Braybrooke-Gibbens, Sian nelson, Sierra Haslem Schroder, Sigvalk Blackthorne, Silje Helene Tangen, Silus, Silvandar, Simen Timian Thoresen, Simon Brooks, Simon Douw, Simon Gannon, Simon Le Guerrier, Simon M N Nielsen, Simon Ridge, Simon Roberts, Simon Stroud, Simone Golding, sin soracco, Sina K., Sixfootbunny, SJ Sanders, Skinny Jim Compton, Slawikaruga, Slybonsai, す み す ボ ブ , Smoothfin, Sneakingfox, Sonarra, Sonofsuns, Soo Thomas, Sophie and Stephan, Sophie Dameron, Sophie Grace Nash, Sophie J., Sophie Lagacé, Sophie Maia House, Sophie Masson, Sophie Nguyen, Sophie Parry, Sorcha Creighton and Ben Cowan, Sorella Fleer, Søren P. Jacobsen, Souji & Pongo, Soul Crack, Space Bamboo, Spencer Wile, Spider Betzalel Perry, Spiranthes, Spire106, Splinters of Jade Podcast, Squidly1, Squig, Squishumz Harumi Kimura, Stacey Anne Cole, Stacey Hayashi, Stacey Kadzewick, Stacey L Figore, Stacy Hosking, Stacy I, Stacy N Enzmann, Stake Belmont 64, Stan!, Stanislav Budarin, Stanislav Nazaruk, Star London, Stark Contrast, Starla Huchton, Stef Maruch, Stefan Laakso, Stefan Uitdehaag, Stefanie Fogle, Steinhäuser, Stenfos, Stenman - Sweden, Step Christopher, Steph “obskeree” Williamson, Steph Bauer, Steph FH, Steph K., Steph Xie, Stephan C, Stéphanie Banneux, Stephanie Conrad, Stephanie D., Stephanie Gauer, Stephanie Latour and Jordan Brudenell, Stephanie Lincoln, Stephanie Nordling, Stephanie Smith, Stephanie Trinity Turner, Stephanie Y Cheng, Stephen & Ashley Sherwood, Stephen A Turner, Stephen Beaudion, Stephen Conway, Stephen D. Sullivan, Stephen Dosman, Stephen G. Rider, Stephen H Brakel Packer, Stephen Hearn, Stephen Napoles, Stephen Shiu, Stephen Tigor, Stephen Walker, Stephen Wong, Stephi Muringer (MISSPLOSION), Stephy McMullan, Sterling Hada, Steve DiOrio, Steve Jasper, Steve Milkowski, Steve Rosenstein, Steve Schleef, Steve Sheets, Steve, Lana, Maia & Logan Burke, Steven C. Wallace, Steven Cronen, Steven Dajic, Steven Gray, Steven Moy, Steven S. Long, Steven Schwartz, Steven Walker, Steven Webb, Stevie Szymkiewicz, Stewart Falconer, Stewart Horne, Steψhen Hazlewood, Stirling Corgi, Stormsister, stormwolf2010, Stuart Atkins, Stuart Browning, Stuart Cleminson, Stuart Frowen, Stuart Fulcher, Stuart L. Burgdorf, Sue Tanida, Suere, Sukekiyo Tanaka, Summer Preuit, Sunshine Zott, Suprita Chatterjee, Susan and Lannie Beaure, Susan E Lund, Susan Fuerstenberg, Susan Hamm, Susan Hoe, Susan Inga, Susan J. Bailey, Susan Jorgenson and Michael Murray, Susan Kennedy, Susan Lane Singley, Susan S., Susanna Krawczyk, Susanne Ledingham and Nori Nishigaya, Susanne Stohr, Suzan & Daniel Campbell, Suzanne Coles, Suzanne Winterberger, Suzette Banick, Suzu Sims, Svafa, Sven Bade, Sven Davis, Sven Svenson, Sylia Hsu, Sylwia Geldmacher, Syrus Jones, T P Kennedy, T. Kiku Annon, T. McDonald, T.J. Hindley, T.M. Stoneburner, T.W. Falls, Tae Lawley-Watkins, tagno25, Takako H. Shimoda, Taki Soma, Taks, Takuman, Takumi, Tal Gur-Arye, Talal Alyouha and Fatma Ashkanani, Talon Spencer, Tam Whalen, Tammy Lupton, Tan Jia Yi, Tan Joyce, Tanaka Kamatari, Tania, Tanja Turja, Tanner Tucker, Tansy Exton, Tantari Kim, Tanya Itkin, Tanyisha Rusbridger, Tara Zuber, Taren JFKDR Robinson, Taryn, TashuCashew, Tasia Karoutsos, Tate Ottati, Tavia Moore, Tawa + Rowan, Taylor Ling, Taylor O’Donnell, Taylor VanWormer, Taylor Whittle, Taytime, Teagan Brady, Team Early, Tebs Yap, Tecla Calogiuri, Teddy Cooper, Teeanna Rizkallah, Teguki, teh ebil bunneh, Tenebrioun, TENG MING KIAT WILLIAM, Teraza Salmon, Teresa D. lynch, Teresa Dendy, Teresa Wagener, terradi, Terry E Roberts, Terynn, Tessa Floreano, Tetsuji Asakawa, Tetsuya Ishibashi, Tev Kaber, Thad Snell, Than Newell, Thanaboon Jearkjirm, Thao Nguyen, Tharathip Opaskornkul, The Amazing Rando, The Bers, the blackhound, The Brannan-Smith Family, The Braskat Arellanes Family, The Brown-Orth Family, The Bustamante Family, the Chapman family, The Duff Family, The Fitches, The Fox Family, The Geek Clan Robinson, The King Family, The Mad Yokai, The Murata Family, The Neilsen-Igaki-Reynolds Clan, The Old Gardener, The One & Owenly, The Rappleys, The Simmons Family, The Szumylos, The Toasty Family, The Travelers Guild, The Very Rev. Robert S. Cristobal, The Vogfather (Steven Leverenz), The Webb Family, The Yōkai Watcher, TheBlazedAce, Thedarkcloak & Cassandra, Theodore GoldsmithHaas, Theodore Orfanos, TherapyFox, Theresa Potratz, Thi Lynn Gallen, Thilo Mischke, Thomas “Direlda” Disher, Thomas Beard, Thomas Boulton, Thomas Bryski, Thomas D White, Thomas Granvold, Thomas Josep Wood, Thomas M Belcher, Thomas M. Cartier, Thomas M. Crockett, Thomas Miyoko, Thomas Payer, Thomas Römer, Thomas Sunderlin, Thuy N Vanorio, Tiah Schindelheim Rodriguez, Tiara L Carlson, Tiarra H., Tib Shaw, Tieg Zaharia, Tiernan Schellenger, Tiffany C Ross, Tiffany Metz, Tiffany Michelle Jeanty-Sinha, Tiffany Moore, Tiffany R Engle, Tiffany Tamaribuchi, Tiffany W.W, Tiger Sionnach Jackson, Tim Cooke, Tim Elrod, Tim Guy, Tim Koneval, Tim Sale, Tim Stroup, Tim Suter, Tim Szczesuil, Tim Wagner, Timan, Timo Naroska, Timo Schließmann, Timothy A. Morris, Timothy Gerritsen, Timothy Grubbs (on behalf of Katherine O’Brien), Timothy J McDevitt, Timothy Joseph Vollmer, Timothy Plymale, Tina Law-Walls, Tinker Tales Studios, Tira Fox, TiTi Navalta, TiTie Volten, TJ Carr, TJ Paul, TJ Volonis, Tobi Carlson, Tobias Gantner, Tobin Thomas Finkenstein, Toby ‘1000’ Hyder, Todd Allen McCullough, todd estabrook, Todd Guill, Todd Kevin Wolynski, Todd S. Tuttle of TNTComics. Com, Toivo Voll, Tom “Festerheart” Watson, Tom and Mel, Tom O’Dowd, Tom Stephenson, Tom Van Blarcom, Tom Voelske, Tomm Hulett, Tommaso Scotti, Tone Bonner, ToneDeaf, Tony Contento, Tony Ferguson, Tony Green, Tony Love and family, Tony Williamson, Toots, Toph Yamato, Tops Marasigan, Tosha AnnMarie Kristensen, Tove Bjerg, Tracey Menzies, Tracey Richardson, Tracy “Kit” Farrell, Tracy Hirano, Tracy Holland, Tracy Lini, Tracy Pinkelton, Traeonna ( ト レ イ ア ン ナ ), Travis J. Porter, Travis Prow, Travis Reardon, Trelvania, Trenton Wynter Brown, Tressa Green, Treve Hodsman, Trevor M Blanchard, Trevor Schadt, Trey Joel Wise, Trickster - J. Bijlsma & N. Vugts, Trina L Short, Trisha Swed, Tristan Ayton, Tristan Giese, Trix Laur, TS Luikart, Tuck V, Tuesday, Tufan Chakir, Tukwyla Lupher, Ty Barbary, Ty Gordon, Ty Kendall, Ty Larson, Ty Stringfellow, Tyler Albers, Tyler Buck, Tyler Chelf, Tyler Heibeck, Tyler Hinthorne, Tyler Hulsey, Tyler J Struble, Tyler James Box, Tyler L. Myers, Tyler Livingston, Tyler Ouellette, Tyler Q. Anderson, Tyler Rickert, Tyler Spicknell, Tyler Stealy, Typhoon Jim, Tyson La Rocca, Uechi108, Ursula M F Thompson, V Shadow, Vaclav Ceska, Valentina Gaëlle Venegoni, ValeriaRin, Valerie Grand Marschner, Valéry Creux, Van Trinh & Lee Eagling, Vanella Mead, Vanessa G., Vasilina Kult, Vassil Lozanov, Vaughan Monnes, Vayne Clennick, Vegard Borgen, Venetia Jackson, Vern McCrea, Vero & Carlos Kitsuné, Veronica Baker, Veronica Beaudion, Veronica Dickerson, Veronica Marie Elizabeth Ann Seton Muller Ensminger Carney, Veronica Skretta, Veronica Yoshida, Vicki Hsu, Victor Acord, Victor J. Tong, Victor Kotnik, Victor Meng, Victor W Allen, Victoria Clements, Victoria Efram, Victoria Hoyle, Victoria Louise Siddle, Vida Cruz, Viet-Tam Luu, VINBERDON, Vince Averello, Vincent Briday, Vincent Docherty, Vincent Grosjean, Vincent Hawkins, Vincent Mak, Vinko Lisnic, Virginia Ann Ullrich-Serna, Virginie V., Viviane Valenta, Vivie Verdi, Vivienne Vincent, Vlad Ardelean, Vlad Dolgopolov, VRex, VulpesAutomata & Yuki, W. David Lewis, W.P. Fleischmann, Wade Harrison III, Walker Glassmire, Walter F. Croft, Wanda Aasen, Warren Jacobsen & Derek Danielson, Wayne H. Suhiha, WeAreGeek, Weasalopes, Wendi morata, Wendy Ashmun, Wendy Walter, Wern212, Wesley Urschel, Wesley Verdin, WiBiTiKi Kaiju Company, WiiGi, @WildcardphotographyTX, Wilhelmina Hoops, Will Anderson, Will Reid, Will Schwab, Will Spooner, Will Svensen, William & Bobbie Moore, William Biersdorf, William Billings, William Blount, William Brubaker, William Ellery Samuels, Ph.D., William Graves, William H. Hettinger II, William Hawks, William Hiles, William K. Leung, William Lodge, William Meeks, William Nelsen, William P. “Ringbearer” Davis, William Patrick Cheney, William S. Thomas, William Seiyo Shehan, William Shuttleworth, William Vidrine, William W. Refsland, Willow Wideman, Wilmer Imperial, Winson Quan, Winston Kou, Winter Skye, winterbc, WolfenM, Wonszu, WoollyRedFox, Worlds of Cyn, Wouter Storme, Woz, WR Swindell, Wren Truesong, Wren Zori Kwiatkowski, Wrinde, Xan, Xavier Stout, @Xavirne, Xenia Rahel and Petra Fruzsina Unger, Xenia Steiner, XiangJun, Xue Yee, Y. van Hout, Yamaneko, Yang-Chieh Lee, 杨 金 辉 , Yasuko Alexander, Yavanna Rey, Yennefer Van Hayden, Yggdraasil, YiffYiff, Yo’el Erez, Yohanesu Größel, Yoshi Ota, Yoshiko Sawai, youkaiya, Youko Kurama, Yuichiro Hara, Yukiko Browne, Yu-Lan Chan, Yunna Erika Strøm, Yuu Gamon, Yves Yernaux, Yvette Absolom, Yvonne Solomon, Zaaaaane, Zacana, Zach M. Peters, Zach P, Zachary Borovicka, Zachary Butler-Jones, Zachary Foster, Zachary Lange, Zachary Morningstar, Zachary Thomas Tyler, Zack Davisson, Zackary Kirk-Singer, Zadara ‘Ahmira’ Phillips, Zain Syed, Zalia, Zandaia C., Zasabi, Zephyrys, Zerik Vishnil, Zeta, Zhevin Akeer, Zigoumi, zljuka_, Zo Guthrie/Fox and Moon Tea, Zoe & Mara, Zoe Piper, Zoe Rose LoMenzo, Zoe Skarupa, Zoï Gkourlias, Zola and Hiro, Zsófia Várady-Páll, Zuno Zoo Y R F R B Haibara Minwa Shūshū Group. Namikko: Makinohara-shi no minwa · densetsu. Makinohara: Makinohara Board of Education, 2008. Jinbunsha Henshūbu. Edo shokoku hyakumonogatari higashi nihon hen. Tōkyō: Jinbunsha, 2005. Jinbunsha Henshūbu. Edo shokoku hyakumonogatari nishi nihon hen. Tōkyō: Jinbunsha, 2005. Kyōgoku Natsuhiko and Tada Katsumi. Yōkai zukan. Tōkyō: Kokusho, 2000. Kyokutei Bakin. Nansō satomi hakkenden. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten, 1990. Mizuki Shigeru. Ketteihan nihon yōkai taizen: yōkai, ano yo, kamisama. Tōkyō: Kōdansha Ltd., 2014. Murakami Kenji. Yōkai jiten. Tōkyō: Mainichi Newspaper Co. Ltd., 2000. Nagano Hitoshi and Higashi Noboru. Sengokujidai no haramushi: Harikikigaki no yukaina byōmatachi. Tōkyō: Kokushokankōkai Inc., 2007. Oikawa Shigeru et al. This is Kyōsai! Tōkyō: The Tokyo Shimbun, 2017. Sasama Yoshihiko. Kaii · kitsune hyakumonogatari. Tōkyō: Yūzankaku, 1998. Takehara Shunsen. Tōsanjin yawa · ehon hyakumonogatari. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Shoten, 2006. Toriyama Sekien. Toriyama Sekien gazu hyakki yagyō zengashū. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Shoten, 2005. Yanagiya Sansa, Hara Masumu and Baba Kenichi. Ōji no kitsune: koten rakugo ōji no kitsune yori. Tōkyō: Akane Shobō, 2016. Yumoto Kōichi. Nihon no genjū zufu: ōedo fushigi seibutsu shutsugen roku. Tōkyō: Tōkyō Bijutsu, 2016. O Database of Images of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai. International Research Center for Japanese Studies. <http://www.nichibun.ac.jp/YoukaiGazouMenu/>. Folktale Data of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai. International Research Center for Japanese Studies. <http://www.nichibun.ac.jp/YoukaiDB/>. I Amabiko Arie Ashiarai yashiki Ashirei Bake ichō no sei Bekatarō Biron Byakko Chibusa enoki Chiko Chōchinbi Dakini Denpachi gitsune Dōmokōmo Fudakaeshi Fukuro mujina Ginko Gotoku neko Hainu Hakuzōsu Hashika dōji Hinoenma Hōnengame Hōsōgami Hossumori Igabō In no kameshaku Isogashi Itsuki Jigoku tayū Jūmen Kame hime Kamisubaku Kan no ju Kanshaku Kazenokami Y Kiko Kinko Kinu tanuki Kizetsu no kanmushi Kitsune no yomeiri Kodama nezumi Kohada Koheiji Kokuko Korōri Koshiita no mushi Koshinuke no mushi Kubikajiri Kuda gitsune Kūko Kyūso Masaki gitsune Mekurabe Mikari baba Minokedachi Mokugyo daruma Nakisubaku Nando babā Narigama Nebutori Nikurashi Nikusui Niwatori no sō Nojukubi Nomori Oi no bakemono Ōji no kitsune Okon gitsune Onashi gitsune Oni hitokuchi Oni no kannebutsu Onji no kitsune Ōtakemaru Otohime gitsune Otonjorō Otora gitsune Senbiki no ōkami Shichinin misaki Shikome Shinigami Shinshaku Shio no chōjirō Shitanaga uba Shoroshoro gitsune Shunobon Subakuchū Suppon no yūrei Suzuhiko hime Tearai oni Tengubi Tengu daoshi Tengu tsubute Tenko Tonshi no kanmushi Tsuchinoko Tsutsugamushi Umidebito Ungaikyō Yako Yakubyō gami Yama orabi Yanagi baba Yanagi onna Yao no kitsune Yō no kameshaku Yogen no tori Yōko Yonaki ishi Zenko Keizōbō Kidōmaru Osaki Osan gitsune