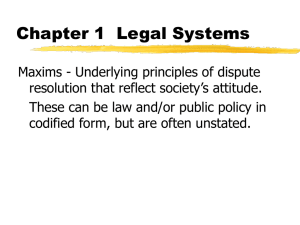

Week 1: Reasons and Arguments CH 9-26 Thursday, January 12, 2023 12:24 AM Notes by: keziaasah@trentu.ca How It Works - As you can see, critical thinking has extremely broad applications. Principles and procedures used to evaluate beliefs in one discipline can be used to assess beliefs in many other arenas. - The basics of good critical thinking are the same everywhere. Here are the common threads that make them universal. Claims and Reasons - Critical thinking is a rational, systematic process that we apply to beliefs of all kinds. Of course, we can really only evaluate beliefs that are made explicit; for obvious reasons, it’s hard to evaluate beliefs that are kept hidden from us. - We can only evaluate our own beliefs once we say (or maybe admit!) to ourselves, “This is what I believe.” And we can only evaluate other people’s beliefs by looking at the things those people actually say or write. So although we are interested in evaluating the quality of beliefs in general, we are mostly limited to evaluating beliefs that someone makes explicit by making some statement or claim. (We’ll say something about the role unstated beliefs can play in arguments and about how to bring them to light and assess them in Chapter 3.) - A statement is an assertation that something is or is not the case. (I am cold, a triangle has three sides, you are not a liar - Belief is just another word for statement or claim. Statements or claims are the kind of things that are either true or false - When you’re engaged in critical thinking, you’re mostly either evaluating statements or formulating them. In both cases your primary task is to figure out how strongly to believe them. The strength of your belief should depend on the quality of the reasons in favour of the statements. - Statements backed by good reasons are worthy of strong acceptance. Statements that fall short of this standard deserve only weaker acceptance at best - Sometimes you may not be able to assign any substantial weight at all to the reasons for or against a statement— there simply may not be enough evidence to decide rationally. Generally, when that happens, good critical thinkers do not just randomly choose to accept or reject a statement. They suspend judgment until there is enough evidence to make an intelligent decision Reasons and Arguments - Reasons provide support for a statement; by providing us with grounds for believing that a statement is true - Arguments: a group of statements in which some of them (the premises) are intended to support another of them(the conclusion) - Premise: In an argument, a statement or reason given in support of the conclusion - Conclusion: In an argument, the statement that the premises are intended to support - The statements (reasons) given in support of another statement are technic ally called the premises. The statement that the premises are intended to support is called the conclusion. - Arguments are the main focus of critical thinking; they are the most important tool we have for evaluating the truth of statements (our own and those of others) and for formulating statements that are truly worthy of acceptance. - Arguments are, therefore, essential for the advancement of knowledge in all fields. In everyday conversation, people use the word argument to indicate a debate or an angry exchange. In critical thinking, however, argument refers to The Power of Critical Thinking Page 1 use the word argument to indicate a debate or an angry exchange. In critical thinking, however, argument refers to the assertion of reasons in support of a statement. - The following are some simple arguments: 1. Because you want a job that will allow you to make a difference in the world, you should consider working for a charitable organization like Doctors Without Borders. Premise: Because you want a job that will allow you to make a difference in the world, Conclusion: you should consider working for a charitable organization like Doctors Without Borders. 2. The Globe and Mail’s Report on Business says that people should invest heavily in gold. Therefore, investing in gold is a smart move. [Premise] The Globe and Mail’s Report on Business says that people should invest heavily in gold. [Conclusion] Therefore, investing in gold is a smart move. 3. When Joseph takes the bus, he’s always late. And he’s taking the bus today, so I’m sure he’s going to be late. [Premise] When Joseph takes the bus, he’s always late. [Premise] And he’s taking the bus today, [Conclusion] so I’m sure he’s going to be late 4. Yikes! This movie is on Netflix, but it was never even shown in theatres. It’s not a good sign when a movie goes straight to video without ever being shown in theatres. This one must be pretty bad. Yikes! [Premise] This movie is on Netflix, [Premise] but it was never even shown in theatres. [Premise] It’s not a good sign when a movie goes straight to video without being shown in theatres. [Conclusion] This one must be pretty bad. 5. No one should drink a beer brewed by a giant corporation. Labatt’s Blue is brewed by a giant corporation, so no one should drink it. [Premise] No one should drink a beer brewed by a giant corporation. [Premise] Labatt’s Blue is brewed by a giant corporation. [Conclusion] So no one should drink it - Some are about what we should believe is true, while others are about what we believe should be done. But what all of these arguments have in common is that reasons (the premises) are offered to support or prove a claim (the conclusion). This logical link between premises and conclusion is what distinguishes arguments from all other kinds of discourse - Inference: the process of reasoning from a premise or premises to a conclusion based on those premises - This mental process of reasoning from a premise or premises to a conclusion based on those premises is called inference. We infer the conclusion of an argument from its premise or premises. Being able to identify arguments, to pick them out of a larger chunk of non-argumentative writing if need be, is an important skill on which many other critical thinking skills are based - consider this passage: Universal pharmacare would cost the Canadian government about $20 billion, which would have to be paid for through taxes. The Canadian government has considered introducing such a plan. That $20 billion paid through taxes would be less than the total amount currently being paid by Canadians privately for their prescriptions. Is there an argument here? No. This passage consists of several claims, but no reasons are presented to support any particular claim (conclusion). This passage can be turned into an argument, though, with some minor editing: Universal pharmacare would cost the Canadian government about $20 billion, which would have to be paid for through taxes. The Canadian government has considered introducing such a plan. The $20-billion plan would cost less than the total amount currently being paid by Canadians for their prescriptions. The Canadian gov ernment should go ahead and institute universal pharmacare. Now we have an argument because reasons are given for accepting a conclusion. - Here’s another passage: Allisha used the online banking app on her iPhone to check the balance of her chequing account. It said that the balance was $125. Allisha was stunned that it was so low. She called her brother to see if he had been playing one of his stupid pranks. He said he hadn’t. She wondered: was she the victim of bank fraud? “What The Power of Critical Thinking Page 2 had been playing one of his stupid pranks. He said he hadn’t. She wondered: was she the victim of bank fraud? “What danger can ever come from ingenious reasoning and inquiry? The worst speculative skeptic ever I knew was a much better man than the best superstitious devotee and bigot.” Where is the conclusion? Where are the reasons? There are none. This is a little story built out of descriptive claims, but it’s not an argument. It’s not trying to convince you, the reader, of anything. It could be turned into an argument if, say, some of the claims were restated as reasons for the conclusion that bank fraud had been committed. - Sometimes people also confuse explanations with arguments. An argument gives us reasons for believing that something is the case—that a claim is true or at least probably true. An explanation, though, tells us why or how something is the case. - Explanation: a statement or statements intended to tell why or how something is the case - Arguments have something to prove; explanations do not. - Look carefully at this pair of statements: 1. Adam obviously stole the money—he was the only one with access to it. 2. Yes, Adam stole the money, but he did it because he needed it to buy food. Statement 1 is an argument. Statement 1 tries to show that something is the case—that Adam stole the money—and the reason offered in support of this statement is that he alone had access to it. That’s why we should believe that he did it. Statement 2 is an explanation. Statement 2 does not try to prove that something is the case (that Adam stole the money). Instead, it attempts to explain why some thing is the case (why Adam stole the money). Statement 2 takes for granted that Adam stole the money and then tries to explain why he did it. - Indicator words: words that are frequently included in arguments and signal that a premise or conclusion is present - These words almost always introduce a premise—something given as a reason to believe some conclusion. Here are some common premise indicators: because, due to the fact that, inasmuch as, in view of the fact, being that, as indicated by - And here are some common conclusion indicators: therefore, it follows that, it must be that, thus, we can conclude that, as a result - using indicator words to spot premises and conclusions, however, is not foolproof. They’re just good clues. You will find that some of the words just listed are used when no argument is present. For example: ○ I am here because you asked me to come. ○ I haven’t seen you since Canada Day. ○ He was so sleepy he fell off his chair. The words “because,” “since,” and “so” are very often used as indicator words, but they are not being used that way in the sentences above - Note also that arguments can be put forth without the use of any indicator words - Arguments almost never appear neatly labelled for identification. They usually come embedded in a lot of statements that are not part of the arguments. The Power of Critical Thinking Page 3