Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome: Definition, Causes, Treatment

advertisement

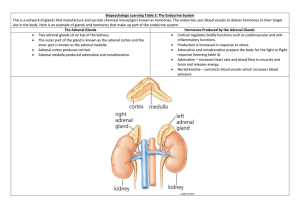

z WATERHOUSE FRIEDERICKSEN SYNDROME. Harry Jim Esther group 566 z DEFINITION Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) or hemorrhagic adrenalitis or Fulminant meningococcemia, is defined as adrenal gland failure due to bleeding into the adrenal glands, caused by severe bacterial infection (most commonly the meningococcus Neisseria meningitidis). Another definition is; acute and severe meningococcemia with hemorrhage into the adrenal glands ETIOLOGY z 1. Most common causes Group B streptococcus Pseudomonas aeruginosa S. pneumoniae Staphylococcus aureus 2. Rarely, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome can be caused by the use of medications that promote blood clotting. 3. Other causes include Low platelet counts Primary antiphospholipid syndrome Renal vein thrombosis Steroid use z Occur usually in infants or children younger than 10, occasionally in adults. The Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome may develop in 10 to 20 percent of children with meningococcal infection. This syndrome is characterized by: ✓ Large petechial hemorrhages in the skin and mucous membranes ✓ Fever ✓ Septic Shock ✓ Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation z CLINICAL PICTURE Onset of the syndrome is dramatically sudden. Nonspecific with fever (initially moderate, then high), rigors, cough, vomiting, and headache. Dysphagia, atrophy of of the tongue, and cracks at the corners of the mouth are also characteristic features. Soon a rash appears; first macular, not much different from om the rose spots of typhoid, and rapidly becoming petechial and purpuric with a dusky gray color and sometimes large purpuric cutaneous haemorrhages often followed by necrosis and sloughing. Exhibits a cyanotic pallor, patients are alert but pale with coldness and cyanosis of the extremities due to generalized vasoconstriction. Hypotension and rapidly leads to septic shock. z COMPLICATION Shock, extensive haemorrhage within the skin and fall into coma. Death usually after a few hours, adrenal insufficiency being the immediate cause. Patients who recover may suffer from extensive sloughing of the skin and loss of digits due to gangrene. MENINGITIS GENERALLY DOES NOT OCCUR. z DIAGNOSTIC METHOD There is hypoglycemia with hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, and the ACTH stimulation test demonstrates the acute adrenal failure. Leukocytosis but if leukopenia is seen, it became a very poor prognostic sign. C-reactive protein levels can be elevated or almost normal. Thrombocytopenia With alteration in and partial thromboplastin prothrombin time time (PTT) suggestive of diffuse intravascular coagulation (DIC). Acidosis and acute renal failure can be seen as in any severe sepsis. Meningococci can be readily cultured from blood or CSF or smears of cutaneous lesions. z PREVENTION Routine vaccination against meningococcus is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control for; All 11-18 year olds 2 People who have poor splenic function (who, for example, have had their spleen removed or who have sickle-cell disease which damages the spleen) 3. Who have certain immune disorders, such as a complement deficiency. z TREATMENT The treatment is as that for meningococcal infection, fulminant meningococcemia is a medical emergency and needs to be treated with adequate antibiotics as fast as possible. Ceftriaxone is an antibiotic commonly employed today. Ceftriaxone is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic. Like other third- generation cephalosporins, it has broad spectrum activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In most cases, it is considered to be equivalent to cefotaxime in terms of safety and efficacy. Benzylpenicillin was once the drug of choice with chloramphenicol as a good alternative in allergic patients. z Addition of adrenal support with hydrocortisone, given intravenously in a dose of 200 mg per square metre body surface per four hours. Hydrocortisone can sometimes reverse the hypoadrenal shock. Hypovolaemia is treated with colloids, dopamine and coagulation factors. Sometimes plastic surgery and grafting is needed to deal with tissue necrosis. z Case 1 A 4 year old, previously healthy boy has a short history of cough and malaise, which had also affected other family members. On attending the accident and emergency department he was found to have a fever of 39°C, an erythematous, blanching skin rash, mild pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy. A diagnosis of viral infection was made and he was sent home. Five days later his condition worsened, with shock and a confluent haemorrhagic rash. His temperature remained high and he was noted to be tachypnoeic. Clotting parameters, including D dimers, were abnormal and his platelet count was low, consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Despite resuscitation, he died. At necropsy there were signs of upper airway infection and z bilateral basal bronchopneumonia, with consolidation. Massive haemorrhage was present in the right adrenal gland, but not the left. There was no evidence of meningitis or haemorrhage elsewhere. Microvascular thrombi were not seen on histology. The cause of death was given as acute adrenal haemorrhage as a result of meningococcal septicaemia. Family members were given antibiotic prophylaxis and the consultant in communicable diseases was informed. Blood cultures and skin scrapings taken before death were unhelpful. Blood and pleural fluid taken aseptically at necropsy grew a heavy pure growth of ẞ haemolytic streptococcus group A. Other surface swabs also grew streptococcus group A. The isolates typed as the M1 strain and contained genes for toxins A and B (the cause of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome). Polymerase chain reaction for meningococcal DNA was negative. z Case 2 Case 2 was a 64 year old man who died suddenly and unexpectedly at home, with no known preceding illness. He had undergone a laparotomy following abdominal trauma at age 14 years, with splenectomy, and had a history of rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate. At necropsy a skin rash was noted. The lungs were congested and massive bilateral adrenal haemorrhages were present (fig 1). The spleen was absent and the upper peritoneum was studded with multiple soft splenunculi. The brain showed severe vascular congestion within the choroid plexus, with mild cerebral oedema. There was no evidence of meningitis or haemorrhage elsewhere and microvascular thrombi were not seen on histology. Postmortem blood cultures, taken aseptically, grew a pure growth of S pneumoniae. z Figure 1 Postmortem histology from case 2 showing massive adrenal haemorrhage, low power and (inset) high power. Haematoxylin and eosin stain. z