Flatland: Creativity, Tradition, and New Dimensions

advertisement

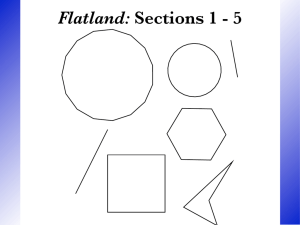

"Upward, Not Northward": Flatland and the Quest for the New ELLIOT L. GILBERT University of California, Davis When perceptible amounts of new phenomenal being come to birth, must we hold them to be in all points predetermined and necessary outgrowths of the being already there, or shall we rather admit the possibility that originality may thus instill itself into reality? William James, Some Problems of Philosophy^ "Your country of two dimensions is not spacious enough to represent me, a [Sphere] of three, but can only exhibit a slice or section of me, which is what you call a Circle. . . . You cannot indeed see more than one of my sections, or Circles, at a time, for you that as I rise in space my sections become smaller. See now, I will rise; and the effect upon your eye will be that my Circle will become smaller and smaller till it dwindles to a point and finally vanishes." Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland Kaluza showed that electromagnetism is actually a form of gravity, but not the What [he] was saying in his bold conjecture was that if we enlarge our vision of the that electromagnetism is only that part of the gravitational field which operates in the extra dimension of space we have failed to recognize. . . What he did provides a classic example of creative imagination. Paul Davies, Superforce^ IN 1980, THE ARION PRESS of San Francisco published a limited edition of Edwin A. Abbott's "romance of many dimensions," Flatland, printing the text on heavy, hand-laid paper in a single fan-fold gathering and providing for each copy elaborately machined aluminum covers and an equally formidable aluminum slipcase. This metallic sheathing of the volume argues, as the publisher no doubt intended it should, for the extraordinary value of the bibliographical objet—the fine paper and beautiful printing—^being so dramatically guarded. But it also, though perhaps less consciously, seems to assert the value of the text itself. ELT: VOLUME 34:4, 1991 suggesting that Flatland, as a cultural artifact of unusual importance, must be carefully protected and preserved. For the purely literary survival of the Flatland text no such heroic precautions are necessary. The slim book by schoolmaster and Church of England cleric Abbott, first published more than a century ago, has since run through twenty-five editions, a number of which are even now in print; thus, the work hardly needs to be rescued from neglect or oblivion.^ What may be in some need of protection and preservation, however, is the thematic significance of this perennially charming story, part sciencefiction adventure, part Socratic dialogue, a significance that appears to have struck even the earliest readers as mysterious. "The book seems to have a purpose,' wrote an 1884 reviewer in the Athenaeum, "but what that may be is hard to discover,'"* a judgment the New York Times seconded the following year when it described the first American edition of Flatland as "a very puzzling book."^ And nearly a hundred years later, Ray Bradbury, in his introduction to the Arion edition, suggests that Flatland continues to challenge interpretation, declaring that "Abbott pretends to be doing one thing, but is truly doing another.'"' So many readers over so long a period have surely not been wrong to sense in Abbott's provocative little book some unstated thesis, and it will be my own thesis here that in Flatland we are dealing with an unassuming but insightftol study of a persistent nineteenth-century preoccupation, the quest for new creative directions in a culture powerfully—if more and more uncomfortably—committed to history and tradition. In seeking sources for that new creativity, Abbott turns for help first to tradition and then to the individual but finds them both inadequate to the challenge, each capable only of reiterating what has already been done, what already exists. By the end of the book, therefore, he is left to posttilate an as yet unidentifiable third direction or third dimension from which, if any vita nuova is in fact possible, such an innovation must come. As to what, in Bradbury's words, Abbott "'pretends to be doing" in Flatland—what, that is, he overtly sets out to accomplish—that seems clear enough; he undertakes to "'edit" the memoir of an inhabitant of a two-dimensional universe who records the consequences of a visit he has received from a three-dimensional intruder. The two-dimensional memoirist's struggle with the concept of a third dimension gives Abbott an opportunity to discuss the analogous problems his own three- GILBERT: QubaT FOR THE NKW dimensional readers have with the concept of a fourth dimension, and as one recent commentator has put it in a testimonial to the author's success, the events and illustrations in Flatland offer "the clearest imagery of the fourth dimension to which [most non-experts] are likely to attain."' The nature of this success of Abhott's should he clearly understood. The editor of a recent edition oiFlatland tries to work up a kind of hogus astonishment in his readers at the prescience of Abhott's achievement by pointing out that when Flatland was written "Einstein was a mere child."® But the critic then goes on to concede that Abbott was writing during years when the abstract concept of multi-dimensionality was quite well known among mathematicians and physicists; just the moment, that is, when the lay public wotild have been ready for some dramatic and picturesque explanation of so intriguing an idea.^ And to offer such an explanation there could have been no one more appropriate than Abbott, who, as headmaster for more than thirty years of the City of London School, the most progressive boys' school of its day, and as the author of nearly fifty books on a wide variety of subjects, had devoted his life to making abstruse knowledge intelligible to non-specialist audiences. The titles alone of some of these books suggest their pedagogical intention: How to Write Clearly, English Lessons for English People, Shakespearian Grammar, designated on the title page as "for the use of schools," and Clue: A Guide Through Greek to Hebrew Scriptures. This last in particular demonstrates both Abbott's ambition and his skill as a popularizer of diffictilt subject matter, being no less than a treatise on the Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic sources and translations of the Bible, written—in Abbott's words—"to be made clear to the simplest intelligence. Even of the details a large number can be mastered without knowledge of any ancient language."^" Other of Abbott's books, especially Through Nature to Christ and The Kernel and the Husk, seek to cast light on the contemporary debate over the proper role of imagination in scientific theory, while still others, notably Philochristus, Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord, Onesimus, Memoirs of a Disciple of St. Paul, and Silanus, the Christian, take on the task of clarifying biblical themes as well as language." These last three works, all best-selling historical romances, stress, in a Carlyleian spirit, the inescapable "presentness'' of the past as well as offering the kind of imaginative, circumstantial recreation of an exotic culture that also makes Flatland so appealing. ELT: VOLUMK 34:4, 1991 Despite their great variety of subject matter, however, Abbott's books tend to return again and again to a few principal ideas, all of which, as we shall see, receive their most memorable expression in Flatland. In the historical romances, for example, particularly Philochristus, Abbott focuses on a favorite subject, represented by the struggle between the Scribes of Galilee, who try to teach the protagonist "not to trust the voice within [him], namely [his] conscience, but only to tradition and authority,"'"^ and Jesus, who speaks "not according to rule, nor out of any books or traditions, but as it were out of himself."" On the whole, in the familiar conflict between historical authority and personal inspiration—between tradition and self—as sources of knowledge, Abbott tends to prefer the interior to the exterior voice, new knowledge to old. But he is also aware of the dangers of an indiscriminate self-reflexiveness, and in his biography of Francis Bacon he quotes with approval Bacon's warning against solipsistically "impress[ing] the stamp of our own image on the creatures and works of God instead of carefully examining and recognizing in them the stamp of the Creator himself."" Abbott even goes so far, in Silanus, the Christian, as to assert that it is "much better (and less misleading) to remain in the old-fashioned belief that a good and wise God created the world in six days than to adopt a new belief that a bad or unwise or careless God—or a chance, or a force, or a power—evolved it in sixty times six sextillions of centuries."^^ Clearly, the ambivalence Abbott felt about this epistemological problem ran deep, perhaps deeper than he knew, though he openly acknowledges the paradox in the introduction he wrote for his father's Alexander Pope concordance, praising the poet on the one hand for his refusal to pursue novelty and on the other for his pioneering of modern English.^® The championing of modern English, and in particular the promotion of an English vernacular over a classical patrius sermo, is another of the forms Abbott's preference for the present over the past—the new over the old—characteristically takes in his works. In Shakespearian Grammar, for example, the writer speaks up for the teaching of English language and literature in the schools, arguing— modestly enough, to be sure—that "it is a positive gain to classical studies to deduct from them an hour or two every week for the study of English."" But he could be much livelier in his advocacy of the vernacular, vigorously attacking Bacon, for instance, for identifying Latin with the authoritative historical record and for considering English ephemeral. incapable of reaching and shaping the future. Of the Latin translation of his own Advancement of Learning Bacon had declared, "It is a book, I think, will live, and be a citizen of the world, as English books are not."'® Abbott takes considerable—if rather unclerical—pleasure in pointing out how wrong Bacon was. Ironically, for all the many ambitious, serious-minded works Abbott composed to promote his ideas about these issues of authority, inspiration, creativity, and faith, only the little jeu d'esprit of a volume he called Flatland, published pseudonymously in 1884, is still read today and has itself lived to be a citizen of the world. It is, of course, easy to understand why the book should continue to attract modern readers for whom the theological conflicts and linguistic skirmishes of the past no longer hold any interest. Speculation about unknown dimensions will always be appealing, and it was surely a stroke of genius for Abbott to populate his mathematical allegory with living geometrical figures—the two-dimensional protagonist is a Square, his three-dimensional visitor a Sphere—lending the story a timeless fairy tale charm. The verisimilitude provided by the Square's solemn efforts to describe the anatomy of Flatlanders and the structure of their social and political systems only adds to that charm. And then, the cultural issues—class warfare, for example, or the condition of women—that Abbott depicts as challenging the book's exotic inhabitants continue, with remarkably few changes in teiTns and form, to confront us today. Though these larger cultural implications of the story ought to have been clear enough to the work's original audience, the puzzlement of the first reviewers, their sense that something besides a discussion of dimensionality, something they couldn't quite grasp, was going on in the book, suggests that from the start Flatland seemed enigmatic. Perhaps the absence of its author's name from the title page was disorienting, depriving readers of the conventional expectations a book acknowledged to be by Abbott might have raised. And indeed there is a sense in which Flatland really is an anonymous work. In all his other books Abbott speaks to us authoritatively—as it were in his own name—on subjects about which he is, and is recognized to be, an expert. In Flatland, on the other hand, though the discussion of dimensionalty requires some small expertise, the voice we hear is very much that of a non-specialist literally an ordinary citizen of Flatland, a Square moyen sensuel who describes the details of his culture without comment or self-consciousness ELT: VOLUME 34:4, 1991 and without any apparent intention to instruct, except in mathematical matters. Naturally, in assembling those cultural details Abbott would have drawn upon his own social, political, and philosophical interests, but as the contemporary success of so many of his other books suggests, those interests closely paralleled the concerns of the society as a whole. Curiously, then, Flatland, for all its quirky geometric fantasy, is also a book to which we can turn today, more confidently than to many more serious historical studies, for an accurate representation of nineteenthcentury life and thought. The book is, indeed, almost an index to the intellectual, spiritual, and artistic preoccupations of the period. One early reviewer finds in the work, for example, "an effective satire on social differences,"'^ and such differences do in fact play a significant role in the story. As Abbott describes it, Flatland society is a rigorously hierarchical one with a structure that appears to be firmly rooted in the curious physiology of its members. The marks of Flatland aristocracy are regularity and manysidedness. All but the lowest orders of the culture (and women) are regular polygons, the equilateral triangles (or middle class) representing the first stage of respectability, squares, pentagons, and higher polygons (or gentlemen and nobles) intermediate levels, and the circles—actually figures with so many sides that they approach true curvature without in fact achieving it—the final or priestly stage. Below the equilaterals is the great swarm of irregular triangles (what the narrating Square refers to, with no apparent sense of impropriety, as "the wretched rabble of the Isosceles"), whose sharp angles constitute a life-threatening danger to the more cultivated, obtuse-angled polygons and who are consequently despised and shunned, though employed as expendable workers, soldiers, and guards. So absolutely is the social structure of Flatland determined by the physical distinctions among its inhabitants that though over the centuries there have been no fewer than 120 rebellions and 235 minor outbreaks instigated by the Isosceles, every one of these violent attempts to reorganize the culture has failed. The satire here of an essentialist British class system in the late nineteenth century is clear enough, and the scope of that satire is soon extended through a consideration of Flatland genetics. As we are informed by the Square, the laws of generation for regular polygons in the society decree that every son shall have one more side than his father, an amusing glance, we may suppose, not just at aristocratic pretensions GILBERT: QUEST FOR THK N E W but at a more general Victorian faith in progress.^" Abbott has, however, a further and subtler point to make here, developing the idea that because progress, defined in such a mechanical way as this, is entirely predictable, it is necessarily sterile and without hope of creativity, only demonstrating the futility of mere accumulation as a means of achieving the new, just as the repeated failures of the Isosceles's rebellions demonstrate the futility of attempting, by conventional means, to change the traditional political structures of Flatland society. The theme is, as I have said, one the author deals with frequently in his other works, and it grows in importance in Flatland as the story proceeds. Another approach to this theme is provided by the culture's virulent misogyny, from the outset one of the book's most conspicuous and controversial features. Not surprisingly, several of the first reviewers singled this element of the story out for special comment, most remarking on its satiric intent. The generally hostile New York Times critic, for example, concluded that what "little sense" the book appeared to make lay in its "appeal for the education of women,"^^ while the more supportive commentator for the Boston Advertiser applauded "the good natured mockery and absurd extravagance"^^ evident in Flatland's denigration of the female. But some early readers apparently mistook Abbott's straight-faced portrayal of that denigration for acquiescence, if not approval, since the preface to the second edition of the work was felt to require a defense of the book's author—ostensibly the Square—against charges of being "a woman-hater.'' And such a judgment of the author's attitude toward women in the story seems still to be possible. In the introduction to the 1980 Arion Press edition of Flatland, for example, Ray Bradbury speaks of the "amusing and perhaps irritating attitudes on women'' in the work but makes it clear that he is not among those irritated. Indeed, he accepts as both seriously intended and reasonable the book's assertion that intellectual and emotional distinctions between men and women, like the physical distinctions between Isosceles and Regular Polygons, are irremediable, simple facts of life that have not changed substantially in the century since Abbott first published Flatland and that are unlikely to change in the next hundred years. In a way, such a variety of readings testifies to the skill with which Abbott has entered into the unreflecting mind of his protagonist to present the condition of women in Flatland. Because (we learn from the Square) Flatland females, regardless of their pedigree or social position. are all born straight lines, they are more dangerous, and inevitably rank lower in the esteem of the culture, than the sharpest angled of Isosceles males. With the merest touch of their pointed bodies meaning death ("What can it be to run against a Woman, except absolute and immediate destruction"'''), these femmes faiales must be rigorously controlled by society, which obliges them, as safety precautions, to render themselves conspicuous by keeping their hindquarters always in motion (Abbott's wry comment, we may assume, on an exaggerated—and threatening— female sexuality), and to warn others of their approach by continually chanting what is called a "peace song." Then, because they lack any angle at all, Flatland ladies are virtually without brains and so receive no mental education, a fact that, according to the Square, burdens males with the necessity of leading a kind of bilingual, and I may almost say bi-mental, existence. With Women, we speak of "love," "duty," "right," "wrong," "pity," "hope,' and other irrational and emotional concepts, which have no existence, and the fiction of which has no object except to control feminine exuberances; but among ourselves, and in our books, we have an entirely different vocabulary and I may almost say, idiom. "Love"' then becomes "the anticipation of benefits"; "duty"' becomes "necessity" or "fitness"; and other words are correspondingly transmuted.^'* Whether we view this as a satire on Victorian over-protection of women, a sardonic version of Abbott's usual interest in the relationship between the patrius sermo and the vernacular, or a remarkable prefiguring of the concept of phallogocentrism,"^ we can certainly understand how, for the Times reviewer, Flatland might have appeared to be appealing for a change in the system of education for women. But behind such a hopeful appeal we, along with Bradbury, can also see Abbott defining, as he had done before in his discussion of the culture's class system, a condition seemingly so rooted in anatomical reality, so deeply entrenched in what might be described as the history of the germplasm, that no imaginable social or political reform can begin to resolve it; that under such circumstances no true creativity is possible. What is perhaps the story's most powerful single episode makes a similar point. During an historical period of unrest called the "Chromatic Sedition,'' a group of despised mutants or "irregulars,'' allying themselves with the culture's dissident females, had sought to change the structure of Flatland society so radically that, among other things, there would no longer have been any practical way of distinguishing between women and 398 GILBERT: Q U I B T FOR THE N E W priests. Abbott's parody here of both the woman's suffrage movement and fin de siecle aestheticism and decadence, together with his recognition of the hnk between these two major revolutionary forces of his own day, appears at first to suggest that change, that a new direction, is not impossible even in a society as rigid as Flatland's. But in the end anatomy proves to be destiny after all as the insurgent women discover that, given the physical limitations of their bodies and their world, they will be worse off under the proposed new freedom than under their traditional constraints. With this, they turn on their deviant allies and eagerly participate in their destruction, demonstrating once again that a desire for the new must be extraordinary indeed that can overcome genetic and geometric necessity. One creative response to a culture like Flatland's, so inflexibly structured by tradition and anatomy as to suppress all individual initiative and render any movement in a new direction impossible, would be, we might suppose, a powerful assertion of self, some ringing announcement of personal sovereignty. But as Abbott goes on to illustrate in his story, such self-assertion, leading inevitably to solipsistic self-delusion, is equally futile as an instrument of creativity. In one of the book's most striking episodes, the Square has a dream in which he is conducted by the Sphere on a visit to Pointland, an anomalous world inhabited by a single creature whose own being constitutes its entire universe. This "king" of what the Sphere calls "the abyss of No dimensions" leads a life of narcissistic contentment, continually singing his own praises in grammatically ambiguous language that makes no distinction between self and other: "Infinite beatitude of existence! It is; and there is none else beside It," the tiny monarch soliloquizes, addressing himself in the third person as the Square and the Sphere look on contemptuously "It fills all space, and what It fills. It is. What It thinks, that It utters; and what It utters, that It hears; and It Itself is Thinker, Utterer, Hearer. It is the One; and yet the All in All. Ah, the happiness of Being!"^'' Disgusted at the complacency of this puny, no-dimensional creature, trapped in what Walter Pater had already famously described as the prison of the mind, the Square tries, with a stern lecture, to shock the little king into a knowledge of his own limitations, into an awareness of the existence of others in the universe. But as the Sphere has predicted, decrying the solipsism of "people who cannot distinguish themselves from the world,' the tiny monarch easily assimilates the intrusive voice into his own private vision by assuming it comes from himself. "Ah, the joy, ah, the joy of Thought!" he chirps still more enthusiastically, his selfjustification slyly mimicking the Miltonic God or perhaps even the Whitmanic ego: "What can It not achieve by thinking! Its own Thought coming to Itself, suggestive of Its disparagement, thereby to enhance Its happiness! Sweet rebellion, stirred up to result in triumph! Ah, the divine creative power of the All in One!"" Creative power, however, is precisely what the king of Pointland lacks, as Abbott is at pains to make clear. For where the only source of knowledge is the self, as in the king's case, one soon exhausts the forms and ideas implicit in that knowledge and permitted by the configuration of that self, and then there is nowhere to turn for new forms and ideas. But how, then, we are left to wonder by the structure of Abbott's argument thus far, can creativity ever be achieved? If history, genealogy, and tradition on the one hand, and solipsistic self-absorption on the other, equally limit life to the established and predictable, to a recapitulation of what has already occurred, where exactly is the new to come from? The logical answer would seem to be that it must come from some source that is neither tradition nor self; and indeed it is to the identification of such a third source that Flatland devotes itself most energetically and originally, the book's nominal search for a third dimension in a twodimensional world—for a new spatial direction—neatly fusing mathematical and metaphysical quests. The key event in the story is the apocalyptic arrival of a Sphere, a solid creature from the universe of three dimensions, in the twodimensional world of Flatland just at midnight on the first day of the third millenium. The Sphere has come to Flatland to preach what he calls "the Gospel of the Three Dimensions," a mission he is allowed to undertake only once every thousand years, and he chooses for his potential apostle a respectable member of Flatland's professional class, a Square who, as a student of mathematics, seems a particularly promising candidate for enlightenment. Hovering above the plane surface of the host world, the visitor announces his presence to the astonished Square, whose immediate problem is to identify the direction from which the voice is coming. Because he is a two-dimensional creature existing in a two-dimensional universe, the Square knows only two directions, those designated on a map by the east/west and north/south axes. The Sphere, GILBERT: QUKST FOR speaking from a third direction, a direction perpendicular to the map-hke plane of Flatland, is, from the point of view of the Square, who lives entirely within the surface of that plane, speaking from nowhere. Not that the Sphere has any trouble making himself visible. This he easily accomplishes by passing his body downward through the Flatland plane, an action he is convinced will infallibly demonstrate the mysterious third direction he has come to reveal. But what to the Sphere seems so self-evidently a movement perpendicular to the Flatland surface is perceived very differently by the two-dimensional inhahitant of that surface. To the Square, who can see only whatever section of the descending Sphere is being cut by the plane at any given moment, his visitor appears first to be a point, then a small circle, then a series of increasingly larger circles, then smaller circles again, then a point, and then nothing.^^ That is, from the perspective of the Square, the Sphere's movement, consisting, as it appears to do, of the expanding and contracting of a circle, is entirely limited to the two familiar directions that define the Flatland plane and gives no hint whatever of perpendicularity. The Sphere decides to try another approach, intending this time to demonstrate the existence of three-dimensional objects by geometric analogy with two-dimensional ones. But he soon runs into a problem of terminology, particularly with the word "upward,' by which he means, once again, the direction perpendicular to Flatland's surface. To the Square, however, who, as the Sphere puts it, "has no power to raise his eye out of the plane of Flatland," "upward" can only mean the direction designated on a map as "Northward," and he says so. To which the exasperated Sphere replies, "No, not Northward; upward; out of Flatland altogether," and suiting action to words draws the terrified Square up into the space above the Flatland plane, up out of his universe's familiar two dimensions into an unimaginable third. It is tempting to see in all this a charming if pointed religious allegory of the sort we might reasonably expect from the author of Philochristus. There are the more than obvious references to gospels and apostles and millenia; there is the scene in which the Sphere, in another effort to illustrate perpendicular motion, gently drops down to touch the complaining Square's "interior," an amusing enactment of the inward response, sometimes indistinguishable from dyspepsia, evoked by spiritual enlightenment; there is the traditional martyr's fate of the Square who, finally convinced of the existence of a third dimension, tries and ELT: VOLUME 34:4, 1991 fails to persuade Flatland's priests of its reality, and in the end is imprisoned as a heretic and madman.^^ Ti-oating these elements of the book as religious allegory has the advantage both of seeing Flatland as something more than social satire or a clever mathematical primer and of confirming, on still another level, the intuition of many readers that the work may "'pretend to be doing one thing, but is truly doing another." In a recent essay, for example, Rosemary Jann examines the story as, among other things, its author's "rebuke to the rigid literalism of fundamentalist religion,' his effort to create a new alliance between scientific knowledge and religious faith.^" Still, the religious reading itself limits the scope of the story to the analysis of a particular kind of creativity, while in Flatland Abbott appears to be trying to press beyond any specific context toward a consideration of the creative act in general, toward an examination of the extraordinary thrust, in a hitherto untried direction, that is required to accomplish anything really new. And when, in the last page of his memoir, the unhappy Square records that "in my nightly visions the mysterious precept, 'Upward, not Northward', haunts me like a souldevouring Sphinx,"^^ he seems clearly to be confirming both the necessity and the elusiveness of that new direction; acknowledging, with fin de .siecle apprehension, the unavoidable but ineluctable demands that the coming century will make on a creativity perhaps unequal to the task. That the one hope for transcending cultural paralysis should be as uncertain as it appears to be at the end of Flatland reflects Abbott's ambivalence about the apocalyptic future which, to the late nineteenth century, appeared to be approaching so swiftly. Such authorial responsiveness to the spirit of the age is one more reason for valuing this little book, worthy after all of archival aluminum, as a kind of unintentional anthology of the period's most persistent concerns. It is remarkable to note how many of those concerns the author is able to touch on in a brief hundred pages: the relative merits of tradition and intuition as sources of knowledge, the burden of history, the appeal of novelty, the deceptiveness of progress, the limitations of hierarchy, the class struggle, the fear of women (often expressed as the threat of the female), the dangers of solipsism, the mysteries of creativity. Of these, this last, properly understood, subsumes all the others. As Kaluza puts it in my epigraph, "if we enlarge our vision of the universe to five dimensions there is really only one force field, and that is gravity.'' GILBERT: QUKST FOR THK NEW In Abbott's own parable of dimensionality, it is the mystery of creativity—what the book's dedication calls "the enlargement of the imagination"—that subsumes all those disparate nineteenth-century philosophical and historical elements catalogued above, elements that appear fragmented to us only because we lack a sufficiently spacious vision to see them as aspects of a single cultural "force field.' Historiography, the celebration of self, the emergence of the female, cultural matters too often studied in isolation from one another, all prove, in their focus on the overriding issue of the age's search for an elusive vita nuova, to be—so to speak—different cross-sections of the same sphere. In Flatland, one way in which fascination with the "mysteries of creativity' expresses itself is through the quest for a new language to define the long sought and greatly to be desired new direction. Champion of a vernacular English during so much of his pedagogical career, Abbott here identifies creativity with linguistic innovation, and in particular with a redefinition (which in the end, however, he is unable to supply) of the word "upward." For the unfortunate Square, imprisoned in the Pateresque cell of his own experience, there can be only the halfunderstood, visionary knowledge of what "upward" is not, can be only the conviction, amounting to a religious conversion, that "upward" is no longer—and can never again be—'"northward." As for what that unimaginable new direction is, if the equivocal conclusion of Flatland fails to say, it nevertheless seeks to prepare readers to know it when they see it: in Abbott's terms, a new dimension, expressed in a new language, leading to a new life. Notes 1. William James, Some Profe/ems o/"/*A//o,sop^V (New York: The Library of America, 1987), 1057, ^ 2. Paul Davies, Saperforce, (New York: Simon and 4. 15 November 1884, 622. 5. 23 February 1885. 6. Ray Bradbury, "Inlroduetion," Flalland (San every decade since the book's first appearance. the auLhor of Einsdnn: His Li/e and Times (Now York: in the U.S. explanalion. In 1880, fouryearsbefore the appearance ELT. VOLUME 34;'!, 1991 Hinton published "Wliul. is ihe Fourth Dimension?" in as Baron Pump\t\glon" The Oxford Thackeray, George thf Duhlin ilniversily Magazine, addressing hia ossay Lo luy audiouco. [linlons An Kpisixlf A quuitcr of i century of Flcidancl elaborated later, on Saintsbury, ed. (London, 1908), 9: 299. 21. New York 7Xmes, 2'S Vchruary ISSh. 22. Boston Atlvertiser, 1885. number of the goomclric fancies in Abbott's book. 10. VA\^'\n \ . Mihoil, Clue: A Guide Through Greek 23. Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland (New York: Dover Books, 1952), 12. 14. Quoted in Francis Sacon: An Account of His Life and Works (London: Macmillan, !885), 4 ! 1 . But nurses—and to learn the vocabulary and idiom of science' (50). Like the Square in Flalland, Abbott I scholars over the original language of the Gospels Rosemary Jann, "Abbott's Flatland: Scientific -s (Spring 1985), 478. Ail^'Tnpt Uj Illustrate 20. Compare Sotn€ of th€ Diffcri^nces HatU'ecH Thackeray's sardonic vision of aristocratic progress from The Book of Snobs: "Old