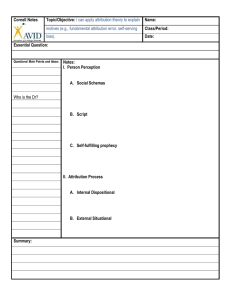

PERSON PERCEPTION When we interact with people in social settings, our perception of them differs from how we see non-living things. This happens mainly because we assess and judge people based on our assumptions and inferences about the intentions behind their actions. We often make assumptions about a person's inner state, which significantly shapes how we perceive and judge their actions. Person perception, a field in social psychology, explores how we form impressions of people we interact with in real or virtual social settings. It also delves into the cognitive process of deciding which information is paid attention to, registered, and encoded during interactions. Understanding how we evaluate this information and how it impacts our subsequent social behavior is also part of the study in person perception. IMPRESSION FORMATION We gather information about people from various sources, like written facts, what others tell us, or the person's observed behavior. During social interactions, we often form impressions based on visible features such as appearance, clothing, and communication style. We may even assume personality traits based on these characteristics. Impression formation is the process of combining diverse information to create a coherent picture of people around us. Understanding people is challenging, so we simplify it by explaining their personality in terms of traits. Traits act as the building blocks for how we perceive others. To form impressions, we often combine information about a person's traits, assigning positive or negative values and calculating an overall impression based on these traits. TRAIT CENTRALITY When we form an impression of a person, certain traits hold more significance than others. For instance, research has shown that we tend to give more weight to negative information about a person than positive details. Asch (1946) conducted a study where he presented two groups with traits describing an imaginary person. In one group, the person was described as "warm," while in the other, "cold" replaced "warm." The results revealed that the traits "warm" and "cold" significantly influenced the overall impression. In the "warm" condition, the person was seen as happy, successful, and popular, while in the "cold" condition, they were perceived as self-centered and unsociable. Another study replaced "warm-cold" with "polite-blunt," showing that the impact on the impression was less significant. This suggests that traits differ in their centrality value, with those having a greater influence on the overall impression considered to have higher trait centrality. FIRST IMPRESSION When we enter an interview room, join a new group, or meet a crucial client, we consciously strive to make a positive first impression. This emphasis on initial impressions stems from the primacy effect, as research (Luchins, 1957) shows that information received early holds more significance than later information. Social psychologists offer explanations for the primacy effect. First, once we form an initial impression, it influences how we process later information about the person. This means that subsequent information is interpreted to align with our first impression. For example, if we initially perceive someone as honest and later discover they haven't returned borrowed money, we might interpret it as financial constraints or forgetfulness, maintaining our initial impression. Second, the primacy effect suggests that we pay more attention to early information, often ignoring or giving less weight to later information once we feel we have enough to form a judgment. Despite its importance, the primacy effect doesn't always occur. In some situations, recent information has a stronger impact, known as the recency effect. This happens when there's a significant time gap after the initial impression, or when we're focused on assessing transient qualities like moods or attitudes. THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION When we interact with people, we focus on their behaviours and their impact. However, we're also curious about the reasons behind these behaviours, requiring us to make inferences beyond our general observations. For instance, if someone is very aggressive in public, we wonder why – is it their nature, a means to achieve a hidden goal, or influenced by the environment? Understanding these reasons helps us predict future behavior to navigate social situations effectively. This process of inferring causes behind others' behaviors is known as attribution. We typically attribute causes in terms of intentions, abilities, traits, motives, and situational factors. Various attribution theories explore how we interpret behaviours to infer their causes. HEIDER’S NAIVE PSYCHOLOGY Heider's Naive Psychology suggests that when we try to understand and infer the personality traits of people in our social interactions, their behavior can be influenced by both their personality attributes and the environment. Heider (1958) introduced the concept of causal attribution, which is the process of deducing the causes behind others' behavior. He argued that people, acting like "naive scientists," use commonsense reasoning similar to the scientific method to find out these causes in everyday interactions. According to Heider, when making causal attributions, people focus on determining whether behavior is attributed to the person's internal state (dispositional attribution) or to environmental factors (situational attribution). For instance, attributing aggressive behavior to internal characteristics like irritability is dispositional attribution, while attributing it to situational factors, such as provocation, is situational attribution. The decision to attribute behaviour to personal dispositions or situational factors depends on our evaluation of the strength of situational pressures on the actor. Strong situational pressure often leads to situational attribution. CORRESPONDENT INFERENCE THEORY Correspondent Inference Theory, proposed by Jones and Davis (1965), suggests that when inferring whether a person's behavior stems from personal dispositions, we initially focus on the intention behind that behavior. We then try to determine if these intentions were caused by inherent traits. However, making such inferences becomes challenging because a single behavior can have multiple effects. To strengthen our attributions, we aim to discern which effects the person genuinely intended and which were incidental. Our decision on which effects were intended depends on factors like how common they are, their social desirability, and how well they conform to normative perspectives. Firstly, the principle of non-common effects states that we infer a person's behavior corresponds to an underlying disposition when the behavior produces an exceptional or uncommon effect that couldn't result from any other behavior. Secondly, socially undesirable outcomes tend to lead us to infer behavior corresponding to an underlying disposition. Engaging in socially desirable behaviors indicates a tendency to appear normal, while low socially desirable behaviors are seen as a reflection of personal disposition. Lastly, the perceiver evaluates the normativeness of the behavior, considering what is normally expected in a given social situation. Behaviors that contradict social norms are attributed to personal dispositions, as they are seen as freely chosen and not forced upon the individual. Correspondent Inference Theory suggests that we are likely to conclude that others' behavior reflects their stable traits when the behavior is freely chosen, yields distinctive effects, and is low in social desirability. COVARIATION MODEL The Covariation Model, proposed by Kelley (1967, 1973), shifts the focus from attributing behavior based on a single instance to considering information gathered from multiple instances. In real-life situations, attributions are often made by observing a person's behavior over time. Kelley suggested that we apply the covariation principle to identify potential causes of behavior. The covariation principle involves examining three types of information: consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness. Consensus relates to how similarly people react to a given stimulus or event. High consensus occurs when many people react in the same way, while low consensus suggests individual variation. Consistency refers to the extent to which a person behaves similarly in different situations over time. High consistency indicates a stable behavior pattern, while low consistency suggests variability. Distinctiveness involves how uniquely a person responds to different stimuli or events. Low distinctiveness occurs when behavior is similar across various situations, whereas high distinctiveness indicates unique behavior in specific situations. The attribution for a behavior depends on the combination of consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness information associated with that behavior. People tend to attribute behavior to internal causes (personal characteristics) when consensus is low, distinctiveness is low, and consistency is high. Conversely, external causes (context or external factors) are often attributed when consensus is high, distinctiveness is high, and consistency is high. The Covariation Model emphasizes the importance of considering multiple instances to increase the accuracy of attributions. ATTRIBUTION OF SUCCESS AND FAILURE In the highly competitive environment we live in, people often assess our successes and failures, attributing them to various factors. For instance, the success of a sports team can be attributed to factors like the team's ability, effort, the difficulty of the task, or even luck. These factors can be categorized into four: ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck. To determine the actual reason behind success or failure, observers first consider the locus of control—whether it's within the individual (internal or dispositional attribution) or caused by external factors (external or situational attribution). Next, they assess the stability of the success or failure, determining whether the reason is a lasting characteristic (stable) or subject to change (unstable). Weiner (1986) proposed organizing these factors in a matrix along the dimensions of internality-externality and stability-instability. For example, ability is viewed as an internal and stable factor, while effort is internal and unstable. Task difficulty is an external and stable factor, while luck is external and unstable. Exceptional performances, whether positive or negative, are generally attributed to internal causes. Consistent performances over time are more likely attributed to stable causes, such as ability or task difficulty, while inconsistent performances are often attributed to unstable causes like varying efforts or luck/chance. Observers tend to attribute average performances to external causes, such as tough competition or misfortune. ERRORS AND BIASES IN ATTRIBUTION FUNDAMENTAL ATTRIBUTION ERROR The Fundamental Attribution Error is the tendency to overemphasize the influence of situational or external factors and underestimate the impact of dispositional or internal factors when attributing behavior. Jones and Harris (1967) demonstrated this error in an experiment with American college students who read an essay either supporting or criticizing the Castro government in Cuba. Participants were informed differently about whether the essay writer freely chose their position or it was assigned to them. Regardless of this information, participants tended to evaluate the writer's true attitude as consistent with the essay. Even when told that the writer had no choice in their position, participants still overestimated the writer's attitudinal disposition, attributing more importance to the choice component (dispositional or internal factor) and underestimating the impact of the no-choice condition (situational or external factor). This error arises from observers not fully applying the subtractive rule, leading to a skewed attribution of behavior. ACTOR OBSERVER BIAS Actor-Observer Bias refers to the tendency to attribute others' behavior to internal or dispositional factors while attributing our own behavior to situational or environmental factors (Jones & Nisbett, 1972). For instance, if a student fails an exam, they might attribute it to factors like a challenging question paper, strict evaluation, lack of preparation time, or sudden family engagements. However, when explaining similar results of other students, the student may attribute them to lack of ability, carelessness, or indiscipline. This bias is observed in clinical settings where practitioners tend to view clients' problems as internal and stable dispositions, while clients attribute their problems to situational factors. The perspective of actors (those involved) and observers (those watching) differs. Actors are more attuned to situational factors influencing their behavior, while observers focus more on the person's behavior rather than the context. As actors, we have a better understanding of our behaviors across various occasions and places, making information about situational factors readily available. Observers, on the other hand, see a person's behavior in a specific instance and situation. This difference in perspective leads to actors making situational attributions for themselves and observers making dispositional attributions for others. Observers often presume a higher consistency in others' behavior compared to their own, contributing to the bias. SELF SERVING BIAS Self-serving bias is the tendency to take credit for our achievements but avoid responsibility for our failures. We often attribute success to our own abilities (internal factors) while attributing failures to external factors like misfortune or task difficulty. This bias stems from a strong need to boost self-esteem when succeeding and to protect self-esteem when facing failures. Miller and Ross (1975) termed attributing successes internally as the self-enhancing bias and attributing failures externally as the self-protection bias. ULTIMATE ATTRIBUTION ERROR The Ultimate Attribution Error extends the self-serving bias to the group level. It reflects a strong tendency to defend our own group while making attributions. Pettigrew (1979) proposed that the relationship between two groups significantly influences the attributions made by members of each group for similar behaviors exhibited by the members of the other group. Positive and socially desirable behaviors of our own group members are attributed to internal qualities, while similar behaviors of the other group's members are attributed to external factors. Conversely, negative behaviors of our own group members are attributed to internal factors, whereas similar behaviors of the other group's members are attributed to internal traits. This error highlights the group-level biases in attributing behaviors based on intergroup relations.