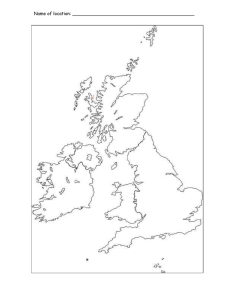

nl y Alisdair Gillespie and Siobhan Weare 1. The English Legal System Alisdair A. Gillespie, Professor of Criminal Law and Justice at Lancaster University and Siobhan O Weare, Senior Lecturer in Law at Lancaster University https://doi.org/10.1093/he/9780198868996.003.0001 Published in print: 31 May 2021 Abstract Pu rp os e s Published online: September 2021 This chapter provides an introduction to the English Legal System. Specifically, it explains the meaning of the terms ‘English’, ‘legal’, and ‘system’. It first provides an overview of the constituent parts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, namely England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. It describes the types of law that exist and attempts to define what law is. It then discusses the English legal system, which is based on common law and is an adversarial system. Keywords: England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, legal, system, common law, adversarial ud y system By the end of this chapter you will be able to: Define the United Kingdom. Identify how many legal systems exist in the United Kingdom. Begin to understand the concept of law and how laws differentiate from mere rules. St p. 1 The English Legal System (8th edn) Begin to think about ‘systems’ and understand the key issues within the English Legal System. Page 1 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 In this introductory chapter the words ‘English’, ‘Legal’, and ‘System’ will be discussed. These words are often used but it is not always clear why they are used in this phrase and why so many modules now refer to the English Legal System. This chapter will also prepare you for the later chapters as it will help put them into context. nl y 1.1 England The first word to examine is that of ‘England’. The question of identity is something that appears to be raised perpetually in the media, and countries are given numerous different wordings. In this country, it is common to refer to living in ‘Britain’, ‘the UK’, or the ‘United Kingdom’. The country does have a formal legal title, that of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The Queen, as O sovereign, has many other titles representing many of the dependent territories that exist but the title is as already stated—United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The latest version of the title became relevant in 1920 when Ireland was partitioned and twenty-six counties were given 2 ↵ demonstrates that ‘Britain’ or, more s 1 independence, forming the Republic of Ireland. The title also Pu rp os e correctly, ‘Great Britain’ is actually the main island grouping of which England is one part. 1.1.1 The constituent parts The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland consists of four countries (although one was originally a principality). The countries are England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. The status of Wales differs from England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Traditionally Wales was a principality (a province ruled by a prince) and this is a term that continues to be used by some, not least because the Crown Prince of the United Kingdom is known as the Prince of Wales and thus the logic, to some, is that it follows that Wales is a principality. Others disagree and argue that Wales is a country and should be accorded that title. In reality the distinction between principality and country is moot and either title could be used although it would seem that many in Wales itself dislike the term principality. Wales does differ from the other constituent countries in that it has not had its own legal ud y system since the sixteenth century, although this is beginning to change. 1.1.1.1 England and Wales Wales does not, as yet, have its own legal system (see, however, the Government of Wales Act 2006 discussed later—see ‘Welsh legislation’) and following the Laws of Wales Act 1535, Wales in effect became legally ‘annexed’ by England and ensured that the laws of England would apply in Wales too. This Act was passed by an English-only Parliament but part of its purpose was to ensure that there St p. 2 Introduction could be Welsh representation in the (then) English Parliament. A further Laws of Wales Act was passed in 1543 and gave further effect to the governance of Wales and the long title of the Act makes express reference to its status as a principality. This was followed by the Wales and Berwick Act 1746 that defined ‘England’ as including all of Wales. This Act was repealed by the Interpretation Act 1978, 3 but prior to this, its extent had been limited by the Welsh Language Act 1967, which re-introduced the concept of Wales as a country in its own right. Page 2 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 technically wrong. It is not the English Legal System; it is technically the Legal System of England and Wales. That this is correct can be seen when one examines the main legal institutions. The senior 4 courts are technically known as the Superior Courts of England and Wales. The body for solicitors, known as the Law Society, is actually the Law Society of England and Wales and the body for barristers, known as the Bar Council, is actually the General Council of the Bar for England and Wales. This extends to judicial offices with the Lord Chief Justice technically being the Lord Chief Justice for England and Wales. This was perhaps most obvious when Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd became Lord nl y Chief Justice and chose an obviously Welsh location for his barony. Welsh legislation As noted earlier, the Government of Wales Act 2006 (GoWA 2006) granted Wales a limited form of O legislative powers. Initially this was through ‘Assembly Powers’ which were, in essence, a form of 5 secondary legislation since each power required the approval of the Privy Council but following a referendum in 2011 (which was required under s 103) the Welsh Assembly was permitted the right to 6 s pass ‘Acts of the Assembly’. These legislative instruments are primary legislation in Wales and, unlike measures, do not require the approval of the Privy Council (although they do, as with UK legislation, Pu rp os e require Royal Assent). However, it would be wrong to say that Wales has yet reached the status of either Scotland or Northern Ireland in terms of devolved legislative powers, not least because its legislative competences are somewhat restricted. 7 A number of Acts of Assembly have been passed, including the Schools Standards and Organisation (Wales) Act 2013, the National Health Service Finance (Wales) Act 2014, and the Renting Homes (Wales) Act 2016. Despite the introduction of these Acts of Assembly, realistically it will be some years before the laws of England and Wales differ dramatically, and even then it will not affect the legal system since courts and both civil and criminal procedure are not devolved matters (cf the position in both Scotland and Northern Ireland). The COVID crisis in 2020 saw, for the first time, considerable difference between the laws of England and Wales. This will be considered more fully in Chapter 20. ud y Commission on Justice in Wales Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd was Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales from 2013 to 2017. Upon his retirement, the Welsh government asked him to chair a commission that reviewed the justice system in 8 Wales. It reported in 2019, recommending that the justice system in Wales and England should be separated. They found that, for example, the use of the Welsh language was inconsistent across courts in Wales, and there was a lack of understanding of local issues. St p. 3 The effect of this is that this book, along with every other book on this topic, and most modules, is The Commission believed that Wales should have responsibility for the justice system, including its prisons, police, and the judiciary. It noted that the Welsh Assembly was starting to produce its own laws, and, therefore, it was time for the Laws of Wales to be recognized as distinct from those in England, even if they were largely the same. More importantly, they noted that it was inappropriate that the professions and courts were administered in England. Page 3 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 While the UK government has not formally responded to the report, in part because it is a Welsh government report, the current Secretary of State for Justice and Lord Chancellor, Robert Buckland MP, has stated that his (and, presumably, the government’s) view is that the legal systems of England 9 and Wales are best shared. Accordingly, it does not seem that there will be formal separation any time soon. 1.1.1.2 Scotland nl y Scotland is a country and joined the United Kingdom as a result of an Act of Union. The history of England and Scotland is probably well known to most readers and involved numerous battles between the two countries, sometimes with England winning, sometimes with Scotland winning. Indeed some of the battles occurred after the union with perhaps the most notable being the uprising led by ‘Bonnie 10 who believed that he was the rightful heir to the throne. O Prince Charlie’ Prior to the countries uniting, England and Scotland shared a sovereign, when King James VI of Scotland assumed the throne of England as King James I. This continued even through the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 when King William III and Queen Mary II jointly ruled both thrones. The countries s were joined by the Act of Union 1707. In fact two statutes were passed as both the English and Pu rp os e Scottish Parliaments had to pass the Act. The effect of the Act was to extinguish the Parliaments of both England and Scotland and create a Parliament of the United Kingdom. This can be contrasted with the position with Wales where Welsh members simply joined the English Parliament. The seat of Parliament was Westminster and this continues to be the case regardless of devolution (see 1.1.2). Perhaps one of the most important aspects of the Act was the preservation of Scots law. Title 19 of the Act expressly preserved the Scottish Legal System and governed how appointments to the senior judiciary would be made. The principle of a separate legal system has continued throughout and devolution has merely altered the mechanics of this. That is not to say that Westminster does not have power to create Scottish laws since it clearly does—it is the Parliament of the United Kingdom—but there is no automatic assumption that laws passed will extend to Scotland (see 1.1.2). Despite the continuing existence of the Act of Union, there has always been a question of whether Scotland should gain independence. Following the formation of the Scottish government after the 2011 parliamentary election, in which the Scottish National Party won a clear majority, an agreement was ud y signed between the Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond and Prime Minister David Cameron on the holding of a referendum on Scottish independence. In September 2014, the Scottish referendum took place. The question on the ballot paper was ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’ Over 3,500,000 Scots voted in the referendum, with the ‘no’ vote winning a majority of 55%, with over 2,000,000 votes. Despite the continued union of the United Kingdom, following the vote the Smith Commission was set up to oversee the devolution of additional powers to the Scottish Parliament. St p. 4 Whilst the Smith Commission was not strongly welcomed by the Scottish National Party, it attracted 11 considerable support from the three main parties at Westminster at that time. As promised, new legislation was brought before the Houses of Parliament and the Scotland Act 2016 was given Royal Assent on 23 March 2016. The Scotland Act 2016 delegates more powers to the Scottish Parliament, including the power to pass laws in areas that were otherwise reserved to Westminster. Page 4 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 Chapter 20, ‘The Future in a Post-COVID World’) has led to calls for another independence referendum. Scotland voted overwhelmingly to stay within the ↵ EU and the First Minister has suggested that the 2014 referendum result has been set aside because voters, at that time, voted to remain within a United Kingdom in Europe. Whilst the Scottish Parliament has unveiled a draft Bill for a further referendum, this would not be sufficient as Westminster must give consent for a referendum to be held. Nevertheless, it would be politically difficult for Westminster to refuse if such a Bill were to nl y be passed by the Scottish Parliament. 1.1.1.3 Northern Ireland Northern Ireland is the most recent addition to the United Kingdom, it being created in 1920. Prior to that Ireland was a whole country and it was a member of the United Kingdom as a result of the Act of O Union 1801. There were many similarities between the Acts of Union 1707 and 1801 and it was intended that it would be a merger: Ireland did not become part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain but transformed it into a new body, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The s merger was political expediency: the two countries had shared the same King since the sixteenth century and there was close cooperation between the Parliaments but it was believed more appropriate Pu rp os e to create a single country. Like Scotland, Ireland retained its own legal status and although there were United Kingdom laws (ie laws that applied across the entire United Kingdom) there were also individual Irish laws. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries pressure grew for Ireland to have more responsibility for its own actions, in part as a reaction to injustices carried out by the British; a series of ‘Home Rule’ Bills (in effect devolution) failed but pressure grew for full independence following a series of insurrections. Eventually the United Kingdom Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920 which would partition Ireland. Twenty-six counties would become ‘Southern Ireland’ and six counties would become ‘Northern Ireland’. The division was broadly upon religious grounds with 12 Ulster (which included the six counties) being mainly Protestant and the twenty-six counties being mainly Roman Catholic. Of course this is a very crude approximation and there was a significant Protestant population in what was to be ‘Southern Ireland’ and vice versa. ‘Southern Ireland’ never came into existence because the twenty-six counties declared independence, ud y forming the Republic of Ireland (Eire). The United Kingdom recognized independence but felt that Ulster was the remainder of the previous Ireland, and, therefore, the UK became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The 1920 Act was eventually repealed by the Northern Ireland Act 1998 which was part of the devolution process (see 1.1.2) but also in pursuance of the Good Friday Agreement, an agreement between the Irish and UK governments to deal with the question of Irish unification. The current position is that both Eire and Northern Ireland remain two separate countries St p. 5 At the time of writing, the response to the vote to leave the EU in the UK-wide referendum (see within the island of Ireland. The government of Northern Ireland is unique within the United Kingdom in that it is based on power-sharing. The leadership of Northern Ireland is held in the First Minister and Deputy First Minister. While the latter sounds as though it subservient, both are equally ranked. They are elected on a joint ticket, requiring a majority of members of the Northern Ireland Assembly, but also a majority of the Ulster Page 5 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 largest party (who has ↵ been a Unionist politician), with the Deputy First Minister being the leader of the largest nationalist party. This book cannot consider the specifics of Northern Ireland political arrangements, but it is worth noting the significant differences between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom. nl y 1.1.2 The United Kingdom Whilst this book is about the English Legal System (but really the Legal System of England and Wales) it is necessary to pause briefly to consider the United Kingdom. The election of a Labour government to the Westminster Parliament in 1997 led to the process of devolution. Theoretically devolution does not affect purely English matters; the law continues to be passed by the Parliament at Westminster. O Devolution principally affects Northern Ireland and Scotland and this is outside the scope of this book although it is likely you will discuss them in Constitutional Law or similar modules. Westminster remains the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the devolution instruments expressly s preserve the right of Westminster to pass legislation that affects both Scotland and Northern Ireland. This is known as ‘extent’. Both prior to and following devolution, the convention is that if an Act of Pu rp os e Parliament is silent as to its extent (ie there is not a section within the Act of Parliament that discusses its extent) then it applies only to England and Wales. If the Act is to apply to either Scotland or Northern Ireland then a section within the Act will expressly state this and also the provisions that apply. Sexual Offences Act 2003 The Sexual Offences Act 2003 was a major piece of legislation that reformed the criminal law relating to sexual offending. Section 142 states: 142 Extent, saving etc. (1) Subject to section 137 and to subsections (2) to (4), this Act extends to England and ud y Wales only. (2) The following provisions also extend to Northern Ireland— (a) sections 15 to 25, 46 to 54, 57 to 60, 66 to 72, 78 and 79, (b) Schedule 2, (c) Part 2, and St p. 6 and Nationalist representatives. The First Minister has traditionally been held by the leader of the (d) sections 138, 141, 143 and this section. (3) The following provisions also extend to Scotland— (a) Part 2 except sections 93 and 123 to 129 and Schedule 4, and (b) sections 138, 141, 143 and this section. Page 6 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 By reading this section (don’t worry about the language used within it, this is explained in Chapter 2) it can be seen that the whole of the Act applies to England and Wales but that only certain parts of the Act apply to Northern Ireland (those mentioned in ↵ subsection (2)). So, for example, ss 1–5 which are not mentioned would not apply in Northern Ireland and even less of it applies to Scotland (principally only Part 2 of the Act and even then ss 93 and 123–9 do not apply). 1.2 Legal nl y The second word to examine is ‘legal’ which is the adjective for ‘law’ but what is ‘law’? One of the first things to note is that we talk about a ‘body of law’ meaning that there is more than one law. Indeed those of you who are studying for a law degree can find that out from your degree title. Most of you will be reading for the degree of LLB (Hons) but do you know what that stands for? It is the O abbreviation for Legum Baccalaureus which means Bachelor of Laws. Why is it that there are two ‘L’s? Law becomes Laws). 1.2.1 Classifying law s It is because in Latin the abbreviation for a plural is to repeat the first letter (whereas we use ‘s’, ie Pu rp os e Before considering what law is (which will require a brief examination of the philosophy of law) it is worth reflecting on the types of law that exist. Law can be classified in various ways and the approach that is taken to the law will be governed by its classification. 1.2.1.1 Substantive or procedural The first division that perhaps has to be discussed is that which exists between substantive and procedural law. It will be seen later that some theorists, most notably Hart, argue that law can be classified into primary and secondary rules. Primary rules are considered to be laws that set out rights, duties, and obligations. Secondary rules determine how the primary rules are to be recognized, interpreted, and applied. Whilst this can be considered relatively simplistic it does assist in our understanding of the distinction between substantive and procedural laws. What is the first thing you think about when you think of law? There is a reasonably high chance that it ud y will be crime (see 1.2.1.3). This is not uncommon because it is one of the few areas of law that most people know something about but also because it is an interesting area of law and one that the media deal with on a daily basis. The actual crime is substantive law, in other words substantive law is that which sets out the rule which must be followed. Where someone is suspected of breaching this substantive law, there has to be an investigation, prosecution, and trial. All of these areas are also governed by laws so that an individual is protected against arbitrary interference by the state. These St p. 7 laws differ from the rule that says a person cannot commit a crime but they are nonetheless laws, and must be followed. These rules are procedural law and they set out the framework by which the substantive law will be determined. Page 7 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 Section 1 Theft Act 1968 states: (1)A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it; and ‘thief’ and ‘steal’ shall be construed accordingly. This is a substantive law. It, in combination with s 7 (which prescribes the punishment for theft), states nl y that a person must not steal. Section 24 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 states: ↵ (a) anyone who is about to commit an offence; (b) anyone who is in the act of committing an offence; anyone whom he has reasonable grounds for suspecting is about to commit an offence; s (c) O (1) A constable may arrest without a warrant— Pu rp os e (d) anyone whom he has reasonable grounds for suspecting to be committing an offence. (2) If a constable has reasonable grounds for suspecting that an offence has been committed, he may arrest without a warrant anyone whom he has reasonable grounds to suspect of being guilty of it. This is procedural law. It sets out the circumstances when a police officer may arrest someone, those being (approximately) that a person has committed, or is about to commit, a breach of the substantive law. 1.2.1.2 Private or public law The next distinction that needs to be drawn is between private and public law. This is a more subtle ud y distinction as it straddles both substantive and procedural law; ie both substantive and procedural law could be either private or public law. A crude but effective separation is to suggest that private law concerns disputes that exist between citizens, and public law is disputes that exist between the state and the individual. It is perhaps the definition of ‘public’ that is more relevant since certain disputes between public bodies may actually give rise to private law matters. St p. 8 Substantive and Procedural Law Page 8 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 Example Private and public law Private Law Rhiannon agrees with Alison to purchase twenty-four bottles of red wine for the price of £150. When Rhiannon comes to collect them, there are only twenty bottles and yet Alison wants the full £150. If not resolved amicably it is quite possible that this dispute will end up before the nl y courts, with Rhiannon suing Alison for breach of contract. This is a classic example of private law as it is a dispute between two parties and does not 13 involve the state in its sovereign capacity. O Public Law Jack, a (fictitious) media commentator made derogatory statements about accountants in a newspaper. Sarah runs a campaign group that attempts to raise the profile of accountants. Sarah wishes to lead a march through Jack’s home town but the local police force refuses s permission. Pu rp os e This is a good example of public law. Sarah may think that the police force is acting unreasonably and may wish to apply to the courts to challenge this decision. This would be done through the process known as judicial review (considered at 17.3) and is a public law matter because it involves the relationship between a private citizen (Sarah) and the state (the police). ↵ AV Dicey, a nineteenth-century jurist, and someone who is considered to be one of the pre- eminent authorities on constitutional law, stated that there was, in England and Wales, no such thing as ‘administrative’ law. By this he meant to contrast the position with the continental-based systems (see 1.3) which have always believed that there is a distinction between public and private law matters. Indeed the continental system created separate courts and legal processes to resolve administrative disputes. Dicey argued that this was not the position within England and Wales because everyone was equal under the law, ie the state was bound by the same law as the citizen. ud y Whilst, during the nineteenth century, this may have been true it is extremely difficult to continue this approach today. The legal system has now created a specific court to deal with administrative law (called the Administrative Court) although it is, theoretically, within the ordinary court system since it merely constitutes part of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice. However, there is no doubt that the system has now become a body of law in its own right and there is now an express and specific procedure that governs administrative disputes. 14 St p. 9 1.2.1.3 Civil or criminal law It may seem that one of the more obvious distinctions to make is between civil and criminal law but, as we will see, this is not always a simple distinction. The distinction does not, as is sometimes believed, necessarily follow the private and public split. Page 9 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 it is easier to say this than to suggest that a crime is anything that is not civil. This is because it is generally easier to identify what is criminal rather than civil. The civil law encompasses many different bodies of law mixing both private and public law. Ordinarily criminal matters can be categorized as public law in that the state is becoming involved in its sovereign capacity in relation to a citizen. In criminal matters the state will ordinarily be the prosecutor (for offences that take place in the Crown Court this will normally be through the sovereign (known as Regina when the sovereign is female and Rex when the sovereign is male) and in magistrates’ courts ordinarily through the Director of Public nl y Prosecutions or Crown Prosecution Service (13.1.1)). Whilst many crimes will have a victim, who will almost certainly be a citizen, it is not necessarily a private dispute between citizens. Indeed the state can, if it so wishes, bring a prosecution regardless of the views of the victim (13.1.2.1). This would make it a public law matter. O However, criminal law can, under certain circumstances, be a private law matter too. Although the state sets out the legal framework and will ordinarily prosecute, there remains in England and Wales the right to undertake a ‘private prosecution’. This will be discussed elsewhere (13.1.5) but in essence means that a private citizen acts as the prosecutor and brings court proceedings. Whilst the state can s intervene it need not do so, and accordingly in that guise it would appear to be private law (because Pu rp os e the state is not present); but the laws are made on the assumption that the state will be the prosecutor so is this not still public law merely instigated privately? This is confusing but does demonstrate an important point: there are no clear answers in law and thus the divisions noted in this chapter will always be somewhat imprecise in practice. What then is a crime? An example of a crime was noted earlier (1.2.1.1) and theft (Theft Act 1968, s 1) is a good example of a simple crime. It is a law that prohibits ↵ something and carries with it a sanction for breaching the law. The courts have traditionally linked punishment with the idea of a 15 crime but this can in itself cause difficulty. There are many examples of situations where a person may appear to receive a punishment but it would not amount to a crime. A good example would be tax. If you need to complete a self-assessment tax form (to let the government know how much tax you must pay) there is a deadline by which you must submit it. If you miss this deadline then a surcharge (which is sometimes even called a ‘fine’) is payable. Is this a punishment? The person who receives it probably thinks so but a person surcharged in these circumstances is not considered to have a criminal ud y record or to have committed a crime. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has always adopted its own approach of what amounts to a ‘crime’ when adjudicating upon the European Convention on Human Rights. 16 In considering whether a matter is a crime the ECtHR said that domestic labelling (ie whether the state considered it to be a crime) was important but not conclusive. Other factors would include the purpose of any sanction and, in particular, its severity. As a general rule the stricter the ‘punishment’ the more likely it is that it will be considered a crime. St p. 10 Civil law is effectively anything that is not criminal. This may appear a trite statement but to an extent 1.2.2 What is law? Trying to define what law is, is a question that has taxed jurists and philosophers for centuries and will undoubtedly continue to do so. Some jurists, most notably Hart, never answered the question, appearing to suggest that it was the wrong question 17 and that the more appropriate question would be to consider what distinguishes law from other regulations or what the purpose of law is. Page 10 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 (eventually) refer to texts on legal theory, philosophy, or jurisprudence to consider (note I am not suggesting you will ever be able to answer) this question. Some of you will have the opportunity to study modules on jurisprudence or legal theory and this will be at the heart of the module. Law has to be more than just a simple set of rules and regulations. Every society has rules and regulations; most families will have a series of informal rules that must be obeyed. Would anyone categorize these as laws? Every university has a set of rules and some will even refer to the documents holding these rules as statutes. There may be a punishment for breaching some of these rules, but nl y again can it be suggested that a university rule is a law? It is sometimes said that a law must be of general application but this need not be the case. In Chapter 2 the concept of Private Acts of Parliament will be discussed and these are of limited application. The simplistic answer is to say that a law is something that is handed down from the state, and that in the United Kingdom it is a rule set out O by the Crown to which we, the subjects of the Crown, are bound. Are there limits to law, or where laws come from, however? It is necessary, at least briefly, to introduce some of the philosophical debates. s 1.2.2.1 Positivism Pu rp os e One of the more important theories of legal governance is known as positivism. There are a number of positivist theorists but the most important are Bentham and Austin, both nineteenth-century philosophers, and Hart, a twentieth-century jurist. Positivism ↵ focuses on what the law is rather than what it should be. It is often criticized as suggesting that even evil laws are valid and should be followed but this is a misunderstanding of positivism, 18 not least because positivism is not concerned with whether a law should be followed but simply what law is. Austin believed in the premise of commands. He believed that an action would either be mandated, 19 prohibited, not mandated, or not prohibited. In other words, he believed that there was an imbalance in the state and that the Sovereign Head of State had the power to issue commands that detailed how a citizen could act, and that any other principles (eg commands from God, individual commands of 20 employers) were not laws but merely moralistic or private requirements. Hart disagreed with this contention. He preferred the notion of rules rather than commands as he 21 believed the notion of ‘command’ was problematic. A significant problem with the idea of commands ud y is that it relies on an unfettered sovereign, ie nobody can command the sovereign. Yet this is not the case in many states where there are limits on what the state can do—sometimes referred to as the ‘Rule of Law’. Another key difficulty Hart had with the command theory is that a command requires a sanction, but does every law have a sanction? If one thinks of procedural law especially it is not easy to think of what a sanction would be. Hart argued that the basis of law was rules and that there were two types of rules: primary rules and secondary rules. St p. 11 It is beyond the scope of this introductory text to consider this question in detail and you should This, to an extent, mirrors the ‘substantive’ and ‘procedural’ rules that were discussed earlier. Hart also believed that these rules had to be set within a context of societal norms, ie that it was not just a fear of sanction that led people to follow the rules but the fact that they believed that it was ‘normal’ to do so. Page 11 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 Primary rules are those that apply directly to citizens. They are the rules that provide what our rights, duties, and obligations are. Secondary rules are those that govern the operation of the primary rules. They put them into nl y effect. 1.2.2.2 Natural law It has been noted already that a particular criticism of positivism is the belief that moral judgements O have little to do with law. Natural-law theorists believe that law is not simply that which our rulers create but that there is a ‘higher law’ that constrains laws. The concept of natural law dates back 22 millennia, probably first appearing in ancient Greek philosophies and was certainly strong in the s early years of the Christian Church with Aquinas, who later was made a saint, being one of the principal proponents of natural law. The influence of the Church in natural law is perhaps not ↵ Pu rp os e surprising since to someone of faith, the ‘higher’ law will be their God. Aquinas believed that there were four types of law: eternal law, natural law, divine law, and human law. 23 He believed that human law derived from natural law, so that natural law requires a law of murder and accordingly society must create such a law. Aquinas also believed that human law had to be compatible with natural law. For a human law to be valid and enforceable it must be consistent with 24 natural law, that being the requirements of the common good. Where a law is incompatible then Aquinas believed that it was unenforceable and unjust. A criticism of natural law is that it is not necessarily practicable. Austin, a positivist, suggested that if a crime was punishable by death it meant very little whether it was an unjust law or not since it would, in all probability, be followed leaving the ‘criminal’ dead but apparently secure in the knowledge that he has become a martyr. The argument of natural lawyers, however, is that it empowers judges not to follow the law. In a common-law-based system (see 1.3.1) it is accepted that judges are the guarantors of law and indeed they can create law. The suggestion is that where a law is incompatible with natural ud y law it should not be followed by judges. Modern natural-law theorists, most notably Finnis, argue that natural law can be equated with ethical 25 conduct and that it is about the creation of laws that are necessary for man to live ethically. This is an interesting approach and demonstrates one advantage of natural law, that it acts as a valid justification for the creation of many of the most fundamental laws (on murder, theft, marriage, and property), since without these basic laws society could not operate. St p. 12 Primary and Secondary Rules Natural law is, to an extent, considered to be the main opponent of positivism and yet there are a number of similarities between them. Both assume the concepts of rules and both accept that a state can produce the rules that surround us. Where the two appear to deviate is that natural law goes beyond positivism and seeks to discuss what the law should say. There is constantly a benchmark against which human laws will be measured, that of the ‘higher’ law. Page 12 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 One of the more recent philosophical theories on law is referred to as the ‘rights thesis’ and is propagated by Dworkin, a twentieth-century jurist. Dworkin rejected the principles of positivism because he believed that law was not simply based on a series of rules but on principles, policies, and 26 more general standards. Some of these standards will include morality and it has been suggested 27 that this can be equated, to an extent, with parts of natural law but it is different in that Dworkin did not believe that there is a ‘higher’ law, merely that the community has institutional morality, ie a nl y common base of principles to which its members adhere. The centre of Dworkin’s criticism is that law is based on the difference between rights (principles) and 28 policy (goals). The importance of policy was that it was a decision for the public good, a decision that influenced the community. This interplays with principles that give rise to individual rights and these may be contrary to the policy goal ↵ albeit for appropriate reasons. More than this, however, he O argues that judges are obligated to decide matters on the basis of principles (rights) and not policy. This distinction is based on a similar premise to the distinction between politics and the law. He later sought an interpretative approach to law. This is not interpretation as we understand it (ie s reviewing a statute and deciding what it means) but has a more philosophical abstract sense. Dworkin Pu rp os e believes that the law is a series of constructive interpretations, that in order for a judge to adjudicate on a problem he must look for a pattern that is discernible in the rights and policies relevant to the 29 issue. This theory of law fits the common-law system (1.3.1) because precedent is an important part of the interpretative approach. The previous decisions of judges help identify a pattern that could lead one to determine what the legal solution to a problem is. Alongside these principles, however, are the moral policies and Dworkin believed that a judge should attempt to make the law as ‘good’ as it can be, meaning that, where there are different alternatives, the one closest to the moral norm may be best. 30 This is also a response to the argument that positivism neglects amoral laws, whereas in the rightsbased approach the amoral law is unlikely to ever be the ‘best’ solution to a given problem and thus the judge will reinterpret the matter. 1.3 System The final word to examine is that of ‘System’. Identifying precisely what a system is can be open to ud y debate but it is probably more than the individual rules or laws and is instead the concept of how law is administered. In the same way that law can be divided into civil and criminal law (1.2.1.3), there are two systems, the criminal justice system and the civil justice system. Thus the system is how the law is to be applied and envelopes some procedural law together with the courts etc. 1.3.1 Common law St p. 13 1.2.2.3 Interpretative/rights theory The English Legal System is an example of a common-law-based system. This can be contrasted with the other principal system which is sometimes known as the civil system (which can be confusing as it does not mean civil as in the distinction between civil and criminal law) and more readily understood as the continental system. These two legal systems can be found throughout the world and their use reflects the geopolitical influence of Britain, Spain, and France. Accordingly, those areas of the world that were parts of the British Empire (eg the United States of America, Canada, Australia, New Page 13 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 whereas those that formed part of the French and Spanish empires (eg Continental Europe, Latin America, and certain parts of Africa) have adopted the continental approach. 1.3.1.1 Common-law system The principal hallmark of the common-law system is, as its name suggests, the recognition of something called ‘common law’. In England and Wales law is not only passed by ↵ Parliament nl y (known as statutory law) but also can develop from the previous decisions of courts. It is for this reason that precedent (which is explained in further detail in Chapter 3 but may be summarized here as the basis upon which certain courts set out rulings which they and other courts must follow) is so important to the common-law system. O The origins of the common law are contested. However, there is broad agreement that it emerged following the Norman Conquest and that King Henry II played a pivotal role in its development. Before the Conquest, and indeed for a period afterwards, different areas of England were governed individually by local laws and customs, rather than by a national legal system. Local courts were s governed by the King’s stewards, with the King himself (perhaps unsurprisingly) presiding over the Pu rp os e King’s Court (the Curia Regis), which followed him as he travelled around the country. The Curia Regis was the origin for the development of the Court of the Exchequer and the Court of Common Pleas, as well as the Court of King’s Bench. When Henry II came to the throne (1154–89) he introduced a series of reforms which sowed the seeds of the common-law system. In 1166 at the Assize of Clarendon, Henry II ordered the non-King’s Bench judges to travel around the country’s circuits and establish the ‘King’s peace’ by deciding cases. In doing so, rather than applying the piecemeal laws found in local areas, the judges applied the new laws of the state which were ‘common’ to all. In 1178, he appointed five members of the Curia Regis to sit permanently at a court in Westminster ‘to hear all the complaints of the realm and to do right’. This court was the origin of the Court of Common Pleas. Eventually the court separated into two, and the Court of the King’s Bench emerged, continuing to follow the King around the country. By the 1170s it was also possible to distinguish the work of the Exchequer from that of the rest of the Curia Regis, dealing with financial litigation and some matters of equity, eventually leading to the creation of the Court of the Exchequer. Thus, by the thirteenth century three senior courts existed, those of the ud y Common Pleas, the Kings Bench, and the Exchequer. The judicial decisions in these cases produced ‘common’ law, applicable to all in the country. The term ‘common law’ was used to distinguish between law that was decided by the Royal Courts in London and which was applied throughout the kingdom (thus a ‘common’ approach to the law), ecclesiastical (Church) law (which remained an important source and application of law until the nineteenth century), and local customary law. Eventually the common law took over the other sources St p. 14 Zealand, and certain African states) have all tended to follow the common-law-based system of law of law, especially as the reporting of decisions became more ordered and it was thus easier to see how judges were applying the law. The common law remains strong today and, whilst it is comparatively rare for the courts to create a new legal principle, there continues to be a significant amount of law that exists without statutory definition. Page 14 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 ↵ Where there is a ‘gap’ in the law the superior courts will sometimes continue to rely on their common-law powers. A good example of this is in respect of the protection of the vulnerable (particularly children) where the Family Division of the High Court of Justice claims an ‘inherent jurisdiction’ which means that it has the power to draw upon the common law to act in the best interests of the vulnerable person. nl y Common-Law Crime Perhaps the best example of a common-law crime is that of murder. The crime of murder is not 31 defined in statute. The definition has evolved through the common law with its basis in the definition given by Coke, an eighteenth-century judge. The definition has been amended by but its definition continues to be a matter of the common law. O 32 statute s Common law v equity Whilst we now refer to the system in England and Wales being a common-law system it is also Pu rp os e necessary to refer to the place of equity. Prior to the Judicature Acts of 1873 and 1875 equity was considered a parallel system to the common-law courts. It is not true to think of it as being separate to the common law as its jurisdiction was inextricably linked to the common law but the common-law courts were restricted to granting damages and so if somebody could not petition the court, or wished something other than damages, the common-law courts could not assist. There was also a belief that the common-law courts were too mechanistic and that the strict rules of law sometimes created unfairness. People began to petition the King (as Sovereign) for justice and he began to delegate these matters to the Lord Chancellor and eventually created a separate series of courts, the courts of Chancery, to resolve such matters. The courts of Chancery proceeded not on the basis of the strictures of common law but on the principles of justice and they could dispense equitable rather than legal resolutions, something based on fairness, and which incorporated other remedies, including injunctions and the ability to recognize beneficial, and not just legal, interests. Equity introduced a series of new and innovative resolutions but it became quickly apparent that in ud y many instances a dispute could be resolved either under the common law or equity and the two parallel systems often conflicted. In the Earl of Oxford’s case 33 the courts were called upon to decide whether common law or equity took priority. It is not necessary to consider the facts of this case in depth and you will probably read about it in Equity & Trusts but, in essence, there was an allegation that a judgment of the common-law courts had been obtained by bribery. The Chancery court issued an injunction preventing the common-law order being enforced and this led directly to a conflict between the two jurisdictions. It was ultimately resolved by it being ruled that in a dispute between the common St p. 15 law and equity, equity would prevail. The Judicature Acts of 1873 and 1875 resolved this tension by unifying the jurisdictions and creating one supreme court of judicature (now embodied by the Senior Courts of England & Wales). All courts— not just the courts of Chancery—were able to exercise the equitable remedies and hence now the part of the High Court that is seen as the successor to the common-law courts (the Queen’s Bench Division) readily issues equitable remedies such as injunctions or mandatory orders. It is important to note the Page 15 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 indeed you will do so when you study the module Equity and Trusts). Equity is based on a series of principles—known as equitable maxims—which continue to be used and which were considered to encapsulate the inherent fairness of equity. 1.3.1.2 Continental system The continental system differs from a common-law system in that it is based on the primacy of written nl y laws. Continental systems tend to be codified, meaning that the laws are all set out in a document. This is not only the hallmark of the continental system since in many common-law countries (most notably America) they have a codified criminal law whereby all of the crimes and procedural rules relating to the criminal justice system are set out in one document, commonly referred to as a Penal Code. O The codification system means that judges are not ‘creating’ new laws or rights but simply interpreting the laws set out by the legislature. Accordingly, if there is a ‘gap’ in the law then it cannot be filled by the judges. However, of course, in practice the concept of ‘interpretation’ is almost as fluid as the idea of judicial creations and the fact that many courts will ‘follow’ the decisions of other judges (even Pu rp os e in the way that the judges desire. s though they arguably do not have a formal system of precedent per se) means that the law will develop 1.3.2 An adversarial system The second hallmark of the English Legal System (and indeed all common-law systems) is that it is an adversarial system. This refers to how cases are adjudicated upon and can be distinguished from the inquisitorial system that is frequently found within the continental system. 1.3.2.1 Adversarial approach The adversarial approach to law is where the adjudication is seen as a contest between two or more sides and it is fought out before a neutral umpire (the judge and/or jury). The judge, whilst able to ask questions, should not seek to become an investigator and should rather concentrate on ensuring that 34 ud y both sides are obeying the procedural rules governing the presentation of their case. A central plank of the adversarial process is the fact that the parties, not the court, call witnesses. Both parties will gather their evidence, including asking witnesses to give statements. The parties will then decide which witnesses they are going to call to give evidence in court. The opposing party is able to challenge this evidence in two ways. The first is through calling their own witnesses who may provide an alternative viewpoint on the issues. The second, and more combative, method is to allow witnesses to be cross-examined. Cross-examination is where a party directly challenges the witnesses’ evidence St p. 16 jurisdictions did not merge and it is possible today to distinguish equity from the common law (and and puts the contrary case to them. The other key principle of the adversarial system is that of the importance of orality. In both the criminal and civil systems of justice there is still the assumption that providing live oral evidence is the best way of arriving at the facts. Indeed in a criminal trial where there is no dispute between the parties as to what the witness will say (ie there will be no cross-examination) then the statement given Page 16 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 by that person will be tendered as evidence. The way it is tendered is that it is read out aloud. It is quite possible, or indeed likely, that giving it to the jury to read would be at the very least as effective but the tradition of oral evidence continues. p. 17 It will be seen later in this book that changes are being made to the adversarial system in order ↵ to take the edge off some of its harshness (see in particular Chapters 17 and 19). However, these are only minor modifications and it is not a shift towards a purely inquisitorial system. nl y 1.3.2.2 Inquisitorial approach The continental system tends to adopt an inquisitorial approach. In this sense the court becomes the investigator itself. Rather than the judge being a neutral umpire, he is given the authority to seek out the truth by asking questions of the witnesses. The respective lawyers seek to control this questioning O by reference to the procedural rules and to this extent it can be argued the roles of counsel and the judiciary are almost mirrored. It has been suggested that one advantage of this model is that it ensures 35 that all relevant witnesses are heard whereas in the adversarial system, if a witness’s evidence is not s helpful to a side, he or she may not be called. Consideration was given to whether the English Legal System should move towards an inquisitorial 36 shift. Pu rp os e approach but the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice argued that this would be a significant cultural Arguably this is correct and it cannot be accidental that common-law systems tend to be adversarial with continental systems being inquisitorial, suggesting that any shift to either model may involve a rethink of the legal system as a whole. Summary In this chapter we have noted that: There is a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Whilst this is our formal state, it is constituted from four parts; England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Historically England annexed the law of Wales and so when we refer to the English Legal System we are actually including Wales too. Scotland and Northern Ireland have separate legal systems, these being retained as part of the Acts of Union ud y that created the United Kingdom. It is difficult to identify what precisely law is and it is probably a philosophical rather than a practical problem. Law is probably a collection of rules governing rights, duties, and obligations but the extent of these rules and where the authority comes from to use them is more open to debate. Law can be divided into different classifications including substantive and procedural, public and private, and St civil and criminal. These classifications affect how we think about law and what the law does. The English Legal System is based on the common law, meaning that judges are able to progress the law themselves. Decisions from previous court hearings still form part of our law. The English Legal System is an adversarial system meaning that a case is adjudicated by two competing sides presenting their evidence with a neutral judge or jury deciding which case they prefer. p. 18 ↵ Page 17 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 Notes 1. It is often erroneously said that the twenty-six counties constitute ‘Southern Ireland’, presumably as the opposite of ‘Northern Ireland’. However, this is both legally incorrect (the formal name of the state is The Republic of Ireland (in English) or Eire (in Gaelic)) and geographically incorrect since the County of Donegal is as northerly as the six counties that constitute Northern Ireland. 2. Since the term is derived from Brittany, a French region, what we understand to be Britain is ‘Great’ (meaning large) nl y Britain. 3. Welsh Language Act 1967, s 4. 4. Constitutional Reform Act 2005, sch 15. O 5. Government of Wales Act 2006, s 93. 6. ibid, s 107. 7. ibid, s 108. s 8. See https://gov.wales/commission-justice-wales <https://gov.wales/commission-justice-wales>. 9. Monidipa Fouzder ‘Buckland: united Wales and England “best for the law”’ (2020) Law Society Gazette, 9 Pu rp os e October (https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/buckland-united-wales-and-england-best-for-the-law/ 5105950.article <https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/buckland-united-wales-and-england-bestfor-the-law/5105950.article>). 10. More properly known as Charles Edward Stuart. 11. The general election of 2015 led to the Scottish National Party becoming the third-largest party in Westminster. The ‘three main parties’ prior to 2015 were the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats. 12. Although ‘Ulster’ is commonly now thought of as being Northern Ireland, it technically includes the counties of Cavan, Donegal, and Monaghan. 13. If the dispute existed between two councils, this would remain a private law matter even though it now involves two public (state) bodies. This is because the dispute is not with the state acting in its capacity as the state, ie the sovereign. ud y 14. Civil Procedure Rules, pt 54. 15. John Adams and Roger Brownsword, Understanding Law (4th edn, Sweet & Maxwell 2006) 147. 16. See, most notably, Welch v United Kingdom (1995) 20 EHRR 247. 17. Brian Bix, Jurisprudence: Theory and Context (7th edn, Sweet & Maxwell 2015) 6. St 18. ibid, 34. 19. James W Harris, Legal Philosophies (2nd edn, Butterworths 1997) 29. 20. ibid, 31. 21. Brian Bix, Jurisprudence: Theory and Context (7th edn, Sweet & Maxwell 2015) 38. 22. ibid, 70. 23. ibid, 71. 24. ibid, 71–2. Page 18 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021 25. ibid, 77. 26. James Penner and Emmanuel Melissaris, McCoubrey and White’s Textbook on Jurisprudence (5th edn, OUP 2012) 83. 27. ibid, 94. 28. ibid, 88–94. 29. Brian Bix, Jurisprudence: Theory and Context (7th edn, Sweet & Maxwell 2015) 95. nl y 30. ibid, 98. 31. Although its punishment now is: see Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965. 32. See Law Reform (Year and a Day Rule) Act 1996. O 33. (1615) 1 Rep Ch 1. 34. Jones v National Coal Board [1957] 2 QB 55. 35. Michael Zander, Cases and Materials on the English Legal System (10th edn, OUP 2007) 375. Pu rp os e s 36. ibid, 377. © Alisdair Gillespie and Siobhan Weare 2021 Related Links Test yourself: Multiple choice questions with instant feedback <https://learninglink.oup.com/ access/content/thomas-concentrate2e-student-resources/thomas-concentrate2e-diagnostic-test> Find This Title St ud y In the OUP print catalogue <https://global.oup.com/academic/product/9780198868996> Page 19 of 19 Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Staffordshire University; date: 07 October 2021