Death-Related Media Impact on Consumer Value & Scope Sensitivity

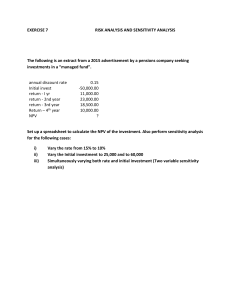

advertisement