Senior Workers' Employment in France: Determinants & Analysis

advertisement

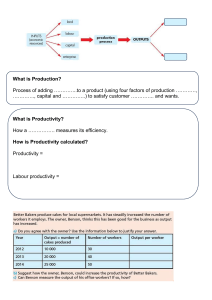

Should I stay or should I go ? The determinants of senior workers’ employment in France. By Leopold Lucquet, Julien Holh and Adrian Alvergne In this paper, we use the SRCV 2019 dataset on living resources and conditions to examine the old-age labour supply. Seniors are defined in this study as people aged between 55 and 64 years old and are further separated between two age cohorts. We evaluate the impact of a set of individual characteristics and work-related indicators on the willingness of seniors to pursue work for another year. Our main finding is that while the 55-59 years-old are sensitive to their health condition and work relationships, the 60-64 years-old work longer if their skillset remains relevant. JEL: J14, J26, J24 Keywords: Retirement, Employment, Labour demand, Economics of the elderly In March 2023, the French government enacted a law reforming the pension system. Since the bill proposal, a violent public outcry aroused and crystallized over one topical question: the shift of the legal retirement age (LRA) from 62 to 64 years old for approximately all workers. The LRA in France is deemed a symbol in the public debate. Changing it should have an impact on the employment of older workers, mainly through two obvious channels: (i) a longer commitment to the firms by delaying retirement (ii) an extended presence of older workers in the labour market (Aubert, 2012). Casting an attentive eye on seniors revealed that older workers are now concerned with issues relative to poverty and a smooth transition to retirement, which can be far from linear: they inform retirement decisions on working conditions and well-being. In 2020, the mean effective retirement age was 62.3 years (62 for men and 62.6 for women) – roughly two years more than in 2010. We thus focus most of our research effort on seniors aged between 55 and 64 years old, as it is the more sensitive to any reform. We know the determinants of labour supply to be multifold when it comes to senior workers. As pointed out by previous research, they fall into financial tradeoffs between the disutility of work and pension benefits - other social factors and incentives aside. On the other side, scholars focusing on firms showed that they can have equivocal hiring behaviour when considering the attributes - or lack thereof - of senior workers. Filling a gap between these strands of literature, this paper attempts to measure the effects of a set of older workers’ individual characteristics and work conditions on their decision to remain in labour for another year. The first papers on retirement decisions built on life-cycle models (Lazear, 1979), framing a tradeoff between work disutility and financial incentives, but failed to highlight the influence of social transfers. A second stream of the literature showed that both the structure and the changes in Social Security heavily inform latecareer labour supply: option models focused on overall income (Stock and Wise, 1990), and forward-looking models on discounted future pensions (Coile and Gru- 1 2 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 ber, 2007). Among Social security parameters, seniors react more vividly to a change in the statutory age of retirement than financial incentives (Behaghel and Blau, 2012; Heywood and Jirjahn, 2016), due to financial illiteracy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011) and heavy social norms (Seibold, 2021). Such models shed light on the spike in labour force exits of American seniors in the 1990s (Blau and Goodstein, 2010), but bear little explanation on the recent surge in senior employment and fail to disentangle the social security effect from other determinants. Adding further strain, the conclusions are inapplicable in France. Among these determinants are health conditions and adapted schedules (Oshio, Usui and Shimizutani, 2018): seniors who work part-time are willing to retire later. A second branch of the literature focused on the demand for senior labour, with the underpinning assumption that seniors have distinguishable features. “Deficit theories” assume that people lose their physical and mental capacities as they age 1 . Among sociologists, some have argued that the last 20 years’ neo-taylorian intensification of labour has made it impossible for firms to maintain low-intensity jobs that used to be suited for older workers (Gollac and Volkoff, 2007). Yet, the research on this topic thus far lacks empirical support (Allen, 2019). Regarding the peculiarities of French senior workers, political scientists held an “early-departure” culture accountable for the lack of labour participation past 55 (Guillemard, 2005). In 2021, more than half of seniors were employed (little less than 80% of the 55-59), this simple statistic shows that early exits from employment do not prevail. The SRCV database (2019) exhibits exit rates of 13% for the 55-64 cohort - 5.9% for the 55-59 and 26.7% for the 60-64. Rather than opting for early-retirement routes, older workers seem to retire at the legal retirement age or past it. As mentioned above, empirical works on the inner defaults of senior workers are weak and conflicting types of analysis coexist to explain senior unemployment. Although dominant effects have already been highlighted in the literature, we lack a coherent vision of the determinants of older workers’ employment along multifold dimensions (characteristics, work environment, etc.). In this study, we use the INSEE 2019 “Statistiques sur les Ressources et les Conditions de Vie” (SRCV, 2019) dataset and for the first time consider the perception of senior workers on both their individual and living conditions to examine their labour supply. We take a stand in looking more deeply into seniors as they see themself fit for the labour market. Our variable of interest is whether seniors intend to stay employed for another year; we differentiate between age groups to point out variations in preferences. Our main result is that while the 55-59 years-old are sensitive to their health condition and work relationships, the 60-64 years-old work longer if their skillset remains relevant. In a broader perspective, this research finds that labour-supply decision can not be accurately explained by individual characteristics and work-related indicators, especially when they are self-reported by workers. The rest of our study is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the French labour market for seniors to help comprehend the dynam1 Seniors who gained very ≪ specific ≫ human capital due to being specialized in one task will lose their productivity potential after a period of unemployment, which explains their low rate of return to employment (Hairault, 2012). Still, several inner characteristics of the senior workforce can influence HR departments in their choice. The value of seniors’ experience is said to have faded following the gradual codification of knowledge. Seniors restricted abilities regarding new technologies and new teamwork practices can also make them less valuable to firms. Mentored project 2 ENS de Lyon 3 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 ics at play and recent trends. Section 3 describes our dataset and discusses the methodology. Section 4 reports our results on the intention to pursue working in the next 12 months. Further discussion of the results is presented in Section 5. I. An overview of the labour market for seniors The labour participation of the 55-64 followed a U-shape pattern Since the 1970s and the emergence of mass unemployment, early retirement policies allowed seniors to leave the job market earlier, in a failed attempt to boost youth unemployment. Access to public early retirement was later restricted, but relaxed unemployment schemes for seniors turned into de facto alternative ways to retirement. Seniors were deemed as an ≪adjustment variable≫ of firms’ costcutting plans (Hairault, 2012). Until 2003, pension reforms were designed to improve the employment of young workers. The assumption that seniors squeeze younger workers out of employment has later been challenged 2 . They translated into a decline in senior labour participation down to a record-low in 2000. Figure 1. The labour market of the 55-64 year-olds Source: Insee (2021) Since then, policymakers swung around and rather focused on increasing seniors’ 2 Munnell and Wu (2013) debunked the myth that older workers should squeeze out younger generations from employment in the USA - with results consistent with studies on OECD countries and France where the employment rate of the 15-24-year-old doesn’t fall with the rise of senior employment. Both cohorts should rather be seen as a positive association in the labour market and within firms. Salem et al. (2010) came short to assert a definitive conclusion for France, although highlighted that older workers’ employment was not at the expense of youth. If not increased, the labour participation of young individuals did not fall with the hiring of seniors. Still, the need to remain cautious about causality must prevail: robust substitution between age groups measures could not be inferred nor simultaneity effects on both young and old workers be controlled for. Mentored project 3 ENS de Lyon 4 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 labour participation. Most reforms shifted the legal age of retirement3 – directly or indirectly, by increasing the duration of social contributions for full-rate pension eligibility. The swooping effect of this sequence is blatant as the employment of seniors jumped to former levels, making it a U-shape pattern (Fig.1) Both policies (statutory retirement age) and broader trends (health, education, sensitivity to the business cycle) are accountable for this recent surge. On the one hand, such policies automatically deferred the effective retirement age, leaving some people with no choice but to delay the liquidation of their pension. On the other hand, raising the age of eligibility encouraged employees or their employers to extend the duration of their employment, in anticipation of a longer retirement horizon: this is the horizon effect (Aubert, 2012). Slimmer routes to early retirement and a rising life expectancy (better health) could explain the turnaround of the millennium. As old-age participation grew, the labour force exits through unemployment and disability schemes remained stable, if not slowed down. Unemployment rates of senior workers were quite steady over the last 50 years. “Neither retired nor employed” older workers accounted for around 16% of the 55–64-year-olds. Public early-retirement schemes were tightened or closed in most OECD countries by the end of the 2010s – and now only account for 3% of retirees in France. As opposed to the 1990s economic slowdown, seniors’ employment rates didn’t chunk after the 2008 recession, showing that late-career labour supply became less sensitive to the business cycle and the level of unemployment. The rising educational attainment, by delaying entrance into the labour market also contributed heavily to the employment rates of older workers, who are more educated than previous generations (Grigoli, Koczan and Topalova, 2018). Differentiating for age groups reveals that the labour market for seniors is changing in lock steps (Fig.2): although the 55-59 years old rose above EU and OECD employment rate standards in the last decade (75.1% in 2021), the 60-64 cohort still fails to meet OECD levels (35% versus 52.2% in 2021). Population projections from Dares, ministère du Travail,, du Plein emploi et de l’Insertion and DARES (2023) indicate that the 55-59 years old already reached a steady employment rate, whereas that of the 60-64 are still expected to grow until 2040 (and stabilize at 60%). French policymakers attempted to boost senior hiring through financial and negotiation incentives. Still, both failed to bear decisive results (Behaghel, Crépon and Sédillot, 2008; Caser and Jolivet, 2014). Looking at senior females shows that among OECD countries, France has now one of the most balanced ratios of female to male older workers (92.5% in 2020), with respective rates of 51.8% and 56%. Since 2000, female employment accounted for 60% of the rise in the senior workforce and converged to male levels (Fig.3). Jointly working or jointly retiring ultimately depends on whether couples value more complementary leisure or revenue (Casanova, 2010; Chiappori, 1988). In couples where only one partner was affected by the French 1993 pension reform, 3 The 1993 and 2003 pension reforms bore insufficient effects on deferring retirement, mainly affecting men (Bozio, 2011), healthy and top-skilled workers (Rabaté, 2019). The 2010 pension reform induced a substitution effect (Rabaté and Rochut, 2020), and retirement was indirectly channelled through two alternative routes: unemployment and disability leave (Hairault, 2012). Regarding workers’ welfare, the impact of delaying retirement age depends on the spillover of education (Garrec and Lhuissier, 2017). When the social benefits of education are lower than private ones, low-skilled workers benefit from higher welfare if solely the skilled workers are affected by reforms. Mentored project 4 ENS de Lyon 5 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 Figure 2. The U-shape evolution of employment rates by age groups Source: Insee (2021) Figure 3. Male and female employment converge since 1975 Source: Insee (2021) the unaffected partner aligned their retirement plan (Stancanelli, 2017). While in France both men and women adapt to their partner’s retirement, the effect is more pronounced for men aligning with women in the USA (Coile, 2003) and for women adjusting to men in Norway. An international comparison amongst relevant OECD countries such as the USA, Germany, and Japan highlights both the progress and the remaining backwardness of France when it comes to employment-to-population ratios (Fig.4). Germany has known the steepest increase in the latter for senior workers for almost 20 years, mostly due to drastic reforms in the labour market with the implementation of part-time contracts, and low-wage jobs which lead to an increase in both old-age poverty and employment, as Germans pursue working for financial reasons, even past the retirement age (Hofäcker and Naumann, 2015). Due to a structural shortage in overall labour supply and concerning old-age poverty rates, Japan exhibits staggering employment rates for seniors, who navigate a labour Mentored project 5 ENS de Lyon 6 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 Figure 4. An international comparison Source: OECD (2021) market that has been adjusted accordingly, with flexible late-career contracts. The French effective age of retirement is also lagging by 3 years on average. This paper does not pursue this international comparison but rather strives to investigate the specific features of French senior labour supply and bring evidence as to why the rates are still lagging. II. Empirical Strategy The INSEE 2019 “Statistiques sur les Ressources et les Conditions de Vie” (SRCV) is a recent cross-sectional database, covering precise and in-depth factors relating to individual living conditions. One question in the surveys underlying the data meets our interest regarding labor participation. Individuals have been asked which professional status they see themselves in for the next 12 months. 3841 senior individuals – aged 55 to 65 years –answered the SRCV survey in 2019. The dummy ≪ Emp ≫ was created to capture whether each individual prospect would stay employed in the next 12 months. Both retirement and overall inactivity, which comprise alternative paths to retirement – unemployment, early retirement, and disability leave - were thus considered as 0 in the binary setting. The weight of personal characteristics and work conditions in labor participation was estimated through a set of dummies. Among inner factors, “health” captures the self-declared state of health of an individual, “comp”, is an indicator of competence based on whether an individual feels able to fully apply his skill range in his position, and “high educ” whether an individual reached secondary education or not. Regarding the professional environment, ”colleagues” takes the value of 1 if the respondent judges he has a good relationship with his co-workers, “fulltime” whether he is working full-time or part-time, and “permanent” captures permanent positions. “female” and “SPC”, the aggregated socio-professional categories, are designated as control variables. In the last model specification, we also control for variations in job satisfaction. Mentored project 6 ENS de Lyon 7 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 Emp = β0 + β1 health + β2 comp + β3 colleagues + β4 f ull time + β5 permanent + β6 high educ + β7 f emale + β8 SP C + β9 job sat The underlying question behind this regression is ≪do I see myself working for another year?≫. Whether this approach is sufficient to model a decision of labour supply is up for debate insofar as individuals may have a larger horizon than one year. As we focus on restricted groups that are near the legal age of retirement, this research builds upon the assumption that one-year projections consist of a fair proxy of retirement decisions. Results are separated into two age cohorts, 55-59 and 60-64. 60-64 are the ages when most people are eligible to full-rate retirement, depending on their individual regime and situation. As a lot of people are already retired, the age group 60-64 captures the situation of a very specific population: those who have already pursued working after 59 and are still considering working more. Not dividing by age groups would thus have led to misinterpretations and severe bias. The underlying question behind this regression is ≪ Do I see myself working for another year? ≫. Whether this approach is sufficient to model a decision of labour supply is up for debate insofar as individuals may have a larger horizon than one year. As we focus on restricted groups that are near the legal age of retirement, this research builds upon the assumption that one-year projections consist of a fair proxy of retirement decisions. Results are separated into two age cohorts, 55-59 and 60-64. At 60-64 most people are eligible to full-rate retirement, depending on their individual regime and situation. In our dataset, almost 49% of the 60-64 cohort consists of retirees, and people out of employment account for 65% of this group. Therefore, the study of the 60-64 years-old captures the situation of a very specific population: those who have already pursued working after 59 and are still considering working more. Not dividing by age groups would thus have led to misinterpretations and severe bias. III. Empirical analysis Expected retirement within 12-months among the 55-59 and 60-64 age groups In our dataset, 48.08% of the 55-64 were retired and 39.9% were employed. As there is a discrepancy between these rates and that of Insee Labor Force Surveys (53.1% employment rate in 2019), our results underestimate the effect of our variable of interest. For the 55-59 years old cohort health has a relatively strong influence on the intention to remain in employment with regard to other explanatory variables. Good health increases the likelihood of staying in employment by 0.256 in the 1st specification (1), and by 0.235 in the 5th specification (5). However, the standard errors of the health variable are relatively high. For model 1, the standard error is 4.22 and for model 6 it is 3.33. We know larger standard errors indicate lower precision and higher uncertainty in the estimated coefficients. Surprisingly seniors’ positive perception of their competence doesn’t raise their likelihood to Mentored project 7 ENS de Lyon 8 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 pursue work for another year. Workers aged 55-59 may not yet have seen their skills fade, and do not overwhelmingly value their competence. They are naturally more sensitive to their state of health than to their level of competence, which has not yet deteriorated enough to have an impact on the decision to remain in employment or not. The health effect is driven by specific and abnormal situations: Table 1—55-59 age group. Employment within 12-months (1) emp (2) emp (3) emp (4) emp (5) emp (6) emp 0.256∗∗∗ (4.22) 0.253∗∗∗ (3.79) 0.250∗∗∗ (3.78) 0.240∗∗∗ (3.32) 0.235∗∗∗ (3.33) 0.165∗ (2.22) comp 0.0614 (1.60) 0.0527 (1.37) 0.0404 (0.99) 0.0440 (1.09) −0.00367 (−0.09) colleagues 0.108∗ (2.18) 0.112∗ (2.29) 0.124∗ (2.27) 0.120∗ (2.27) 0.0874 (1.64) full time 0.0375 (1.17) 0.0320 (0.94) 0.0302 (0.87) 0.0348 (1.02) permanent 0.124∗∗ (3.06) 0.127∗∗ (3.01) 0.181∗∗∗ (3.99) 0.164∗∗∗ (3.70) health high educ 0.0314 (1.32) female SPC −0.0220 (−0.81) −0.00468 (−0.18) 0.0632∗∗ (2.62) 0.0628∗∗ (2.67) −0.00559∗∗∗ (−4.35) −0.00505∗∗∗ (−4.05) 0.189∗∗∗ (4.39) job satisfaction 0.621∗∗∗ (10.39) Constant Observations 1105 0.470∗∗∗ (5.66) 950 0.338∗∗∗ (3.69) 949 0.335∗∗∗ (3.33) 835 0.545∗∗∗ (4.98) 831 0.506∗∗∗ (4.65) 829 t statistics in parentheses ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 even if 55-59-year-olds are more likely than younger people to see their health deteriorate, work disability due to illness remains scarce. Indicators of stress and physical intensity at work are not independent, so only the general health indicator is kept in the model. The willingness to stay employed is reinforced for workers with indefinite contracts (permanent); although working part or full-time doesn’t affect the likelihood to remain employed. All else held fixed, seniors engaged in a permanent tenure have a 0.164 (6) - or 0.181 (5) - higher chance of staying in employment than seniors who aren’t. Keep in mind that this is a probability of their decision to leave that doesn’t necessarily encompass the firm’s decision. Whether seniors enjoy great relationships with their colleagues also increases their likelihood to remain in the labour force by 0.120 (5). As far as gender differences apply, being a female doesn’t increase the probability of quitting the labour force. If anything, women are more inclined to stay employed – although statistically significant, the coefficient is very low (0.0632 in specification 5). Controlling for Socio-professional categories, the effects mentioned above hold, and changes in SPC don’t bear an effect of magnitude on the likelihood to retire in the future. Finally, it is impossible to conclude the effect of educational attainment on the decision to retire. Although in theory, the longer the studies the longer workers have to contribute to reach pension eligibility. This assumption may be counter- Mentored project 8 ENS de Lyon 9 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 balanced by an income effect tied to higher educational attainment, as wealthy individuals may be inclined to retire earlier. As we do not have data on income, we leave this for further research. A positive job satisfaction increases the probability of a senior seeing themself work for another year but rules out the ”colleagues” effect. Work relationships are arguably comprised in the overall job satisfaction indicator. Interpretation of the intercept is tricky with binary dependent and explanatory variables. Yet, it appears that holding every variable at zero, the probability of remaining in the labour force for another year revolves around 0.5. Conversely, the 60-64 cohort is less sensitive to health concerns than to their perceived competence and technical ability to continue working. It is reasonable to think that a selection on the level of physical condition has already been at play beforehand and that the 60-64 cohort is filled with a peculiar senior population in employment, less affected by poor health. After running all specifications, we Table 2—60-64 age group. Employment within 12-months (1) emp (2) emp (3) emp (4) emp (5) emp (6) emp −0.0150 (−0.16) −0.0159 (−0.16) 0.0195 (0.17) 0.0240 (0.22) −0.0182 (−0.17) comp 0.154∗ (2.28) 0.141∗ (2.05) 0.158∗ (2.06) 0.167∗ (2.17) 0.135 (1.70) colleagues 0.0142 (0.17) 0.0211 (0.25) 0.0549 (0.55) 0.0730 (0.72) 0.0520 (0.51) full time −0.00538 (−0.11) 0.00634 (0.12) 0.0376 (0.66) 0.0358 (0.63) permanent −0.0442 (−0.73) health 0.00599 (0.07) high educ −0.109 (−1.79) 0.0859 (1.78) female SPC −0.0976 (−1.42) −0.101 (−1.45) 0.0653 (1.18) 0.0639 (1.17) 0.0860 (1.77) 0.0915 (1.87) −0.00149 (−0.59) −0.00136 (−0.54) job satisfaction 0.120 (1.54) 0.686∗∗∗ (8.72) Constant Observations 541 0.540∗∗∗ (4.38) 446 0.589∗∗∗ (4.18) 445 0.517∗∗ (3.09) 388 0.487∗ (2.34) 382 0.467∗ (2.18) 380 t statistics in parentheses ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 find perceived competence as the only significant explanatory variable: it lifts the probability to pursue work by 0.154 (2) and 0.167(5). Here, the job satisfaction coefficient, although identical (at 0.120) as that of the 55-59 age group, loses its significance. We note here again a high standard error of 2.05 (2) and 2.17 (5). That all but the competence determinant are uncorrelated and insignificant with future employment makes the interpretation of the results uneasy. The 60-64 age group could be so utterly different from their younger counterparts that none of the determinants of the 55-59 years-old’s employment applies to their own work Mentored project 9 ENS de Lyon 10 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 behaviour; or the results on the latter cohort should be revisited and questioned. As examining for other determinants than those listed in our regression tables is not part of our research plan, we leave this conendrum unresolved, but cautious that our results may be revisioned. Also, for each age group, it remains impossible to rule on the influence of education level in the decision to stay or leave employment; the coefficients vary between negative and positive values in the 95% confidence interval (and they are very small). Seniors appear far from being a homogeneous category of workers, as predicted in the snapshot of the labour market in the introduction, and differentiating between age groups proves to be mandatory in order to understand their motivation to remain in employment or to leave the labour force. IV. Discussion An inclusive working environment –namely in the form of good relationships with colleagues and satisfaction at work – tend to motivate workers aged 55-59 to stay in the labour force. This could be interpreted as the direct effect of corporate culture toward seniors, and fuel interest in studying the empirics of the early departure culture. After 59, the senior’s perception of their own competence plays a positive role in their participation. This could be a hint at the depreciated value of senior knowledge theory. The fact that the “younger” category of seniors is not affected by their perceived competence would tend to confirm this insight. Other tested factors have failed to demonstrate any effect, including the one which was said to have been effective in Japan – part-time and high education as determinants of a more senior-friendly workplace. As much as our regression results may indicate statistically significant and substantial relationships between working conditions, health and old-age labour supply these do not stand as causal explanations. This paper doesn’t intend to comprehensively model French labour participation but to test the influence of individual and work-related factors. Some missing variables could influence the ones tested and undermine this paper’s results. Still, no suspiciously high impact of tested factors is witnessed. Although this paper strives to examine some of the above-mentioned parameters, it is impossible not to leave other factors aside. Among the latter should be considered overall household analysis. There already is a recent strand of literature investigating couples’ joint retirement behaviour, but further research should also dive into other family incentives motivating retirement or late employment. As such, many major labour supply determinants are missing, namely regarding pension regime and financial status – hardly available in cross-sectional individual data covering workplace subjects. This is blatantly displayed in the significant value of the intercept. Our variables have been constructed as dummies, this makes our analysis and regressions more practical, but we have no nuance on the intensity of the determinants. Another important bias is that some variables influence each other. This is why we considered in our regressions that variables like ”stress” were already included in the variable ”health”. Attrition bias is also present in our population. When performing our regressions and with the presence of many missing values in our different independent variables, a large number of observations are deleted. The standard errors from our regressions are relatively high as Mentored project 10 ENS de Lyon 11 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 we have seen for the ”health” variable in Table 1 or the ”competence” variable in Table 2. We believe that this is due to several factors, notably the number of observations and therefore the attrition of the variables in our regressions, the inclusion in our model of irrelevant variables which increases the standard error. Several techniques can be used to reduce these standard errors such as the logarithmic transformation of variables or the use of more advanced regression techniques such as the ridge, lasso, or elastic net. Another flaw lies in the SRCV database itself. The variables capturing personal characteristics, such as competence, relationship with colleagues and state of health are all self-declarations. These are good indicators of how well the individual feels, and how these feelings shape his horizon toward retirement. As inherently subjective, they are less relevant regarding the actual capacity and working conditions. Although social categories were used as a control, further studies diving into sociological differences in perceptions at work would be welcomed. Furthermore, the individual’s interpretation of his self-capacity could also be the result of corporate policy. Whether the relationship with colleagues depends on individual social skills or work conditions installed by the management can be left to the reader’s judgment. The same goes for competence, which could also be subject to changes according to firms’ policies in senior training. Overall, this paper’s conclusions should be backed by cross-section data using annual interviews to allow in-depth comparisons between companies’ and employees’ points of view. This contribution would be instrumental in discussing the respective effect of the early departure culture and of individual characteristics. Comparing managers’ and seniors’ perspectives would also help shape more efficient inclusion policies. V. Conclusion Aside from social security, wealth and financial incentives for retirement, seniors do adjust their late-career labour supply on more personal grounds. They at least consider their health condition, skillset and work environment. Other determinants of interest disappointed: no empirical support could be provided to conclude on the influence of educational attainment, part-time work or even socio-economic line of work. VI. Acknowledgements We would like to thank our supervisor J. Goupille-Lebret for his help and the Economics Department of ENS de Lyon for the opportunity to embark on this research project. References Allen, Steven G. 2019. “Demand for Older Workers: What Do Economists Think? What Are Firms Doing?” National Bureau of Economic Research. Aubert, Patrick. 2012. “L’≪ effet horizon ≫ : de quoi parle-t-on ?” Revue française des affaires sociales, , (4): 41–51. Place: Paris Publisher: La Documentation française. Mentored project 11 ENS de Lyon 12 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 Behaghel, Luc, and David M. Blau. 2012. “Framing social security reform: Behavioral responses to changes in the full retirement age.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(4): 41–67. Publisher: American Economic Association. Behaghel, Luc, Bruno Crépon, and Béatrice Sédillot. 2008. “The perverse effects of partial employment protection reform: The case of French older workers.” Journal of Public Economics, 92(3-4): 696–721. Publisher: Elsevier. Blau, David M., and Ryan M. Goodstein. 2010. “Can social security explain trends in labor force participation of older men in the United States?” Journal of human Resources, 45(2): 328–363. Publisher: University of Wisconsin Press. Bozio, Antoine. 2011. “La réforme des retraites de 1993: l’impact de l’augmentation de la durée d’assurance.” Economie et statistique, 441(1): 39–53. Publisher: Persée-Portail des revues scientifiques en SHS. Casanova, Maria. 2010. “Happy together: A structural model of couples’ joint retirement choices.” Caser, Fabienne, and Annie Jolivet. 2014. “L’incitation à négocier en faveur de l’emploi des seniors. Un instrument efficace ?” La Revue de l’Ires, 80(1): 27– 48. Place: Noisy-le-Grand Publisher: I.R.E.S. Chiappori, Pierre-André. 1988. “Rational Household Labor Supply.” Econometrica, 56(1): 63–90. Publisher: [Wiley, Econometric Society]. Coile, Courtney. 2003. “Retirement incentives and couples’ retirement decisions.” Coile, Courtney, and Jonathan Gruber. 2007. “Future Social Security Entitlements and the Retirement Decision.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2): 234–246. Publisher: The MIT Press. Dares, ministère du Travail,, du Plein emploi et de l’Insertion, and DARES. 2023. “Les seniors sur le marché du travail en 2021.” Garrec, Gilles Le, and Stéphane Lhuissier. 2017. “Differential mortality, aging and social security: delaying the retirement age when educational spillovers matter.” Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16(3): 395–418. Publisher: Cambridge University Press. Gollac, Michel, and Serge Volkoff. 2007. “Santé au travail : une dégradation manifeste.” 179(2): 3–3. Place: Auxerre Publisher: Éditions Sciences Humaines. Grigoli, Francesco, Zsoka Koczan, and Petia Topalova. 2018. “Drivers of labor force participation in advanced economies: Macro and micro evidence.” Guillemard, Anne-Marie. 2005. “Politiques publiques et cultures de l’âge. Une perspective internationale.” Politix, 72(4): 79–98. Place: Louvain-la-Neuve Publisher: De Boeck Supérieur. Hairault, Jean-Olivier. 2012. Pour l’emploi des seniors. Assurance chômage et licenciements. Rue d’Ulm. Mentored project 12 ENS de Lyon 13 SENIOR EMPLOYMENT IN FRANCE May 2023 Heywood, John S., and Uwe Jirjahn. 2016. “The hiring and employment of older workers in Germany: A comparative perspective.” Journal for Labour Market Research, 49(4): 349–366. Publisher: SpringerOpen. Hofäcker, Dirk, and Elias Naumann. 2015. “The emerging trend of work beyond retirement age in Germany.” Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 48(5): 473–479. Publisher: Springer. Insee. 2021. “Emploi - Séries longues Activité, emploi et chômage en 2021 et en séries longues | Insee.” Lazear, Edward P. 1979. “Why is there mandatory retirement?” Journal of political economy, 87(6): 1261–1284. Publisher: The University of Chicago Press. Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. “Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States.” Journal of pension economics & finance, 10(4): 509–525. Publisher: Cambridge University Press. Munnell, Alicia, and April Wu. 2013. “Do Older Workers Squeeze Out Younger Workers?” Discussion Papers. Number: 13-011 Publisher: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. OECD. 2021. Pensions at a Glance 2021 : Paris:OECD Editions. OECD and G20 Indicators. Oshio, Takashi, Emiko Usui, and Satoshi Shimizutani. 2018. “Labor force participation of the elderly in Japan.” In Social security programs and retirement around the world: Working longer. 163–178. University of Chicago Press. Rabaté, Simon. 2019. “Can I stay or should I go? Mandatory retirement and the labor-force participation of older workers.” Journal of Public Economics, 180: 104078. Publisher: Elsevier. Rabaté, Simon, and Julie Rochut. 2020. “Employment and substitution effects of raising the statutory retirement age in France.” Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 19(3): 293–308. Publisher: Cambridge University Press. Salem, Mélika Ben, Didier Blanchet, Antoine Bozio, and Muriel Roger. 2010. “Labor force participation by the elderly and employment of the young: The case of France.” In Social security programs and retirement around the world: The relationship to youth employment. 119–146. University of Chicago Press. Seibold, Arthur. 2021. “Reference points for retirement behavior: Evidence from german pension discontinuities.” American Economic Review, 111(4): 1126–65. Stancanelli, Elena. 2017. “Couples’ retirement under individual pension design: A regression discontinuity study for France.” Labour Economics, 49: 14–26. Publisher: Elsevier. Stock, James H., and David A. Wise. 1990. “The Pension Inducement to Retire: An Option Value Analysis.” In Issues in the Economics of Aging. 205– 230. University of Chicago Press. Mentored project 13 ENS de Lyon