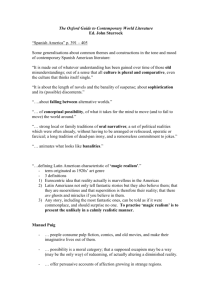

Magic Realism in the postcolonial: Chronicle of a Death Foretold Aditi Behl Nov 20, 2020 7 min read Magic Realism (el realismo magical) was a term first coined in 1949 by the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier to describe the matter-of-fact combination of the fantastic and every day in Latin American fiction. The term magic realism, originally applied in the 1920s to a school of painters, is used to describe the prose fiction of Jorge Luis Borges in Argentina, as well as the work of writers such as Gabriel García Márquez in Colombia, Isabel Allende in Chile, Günter Grass in Germany, Italo Calvino in Italy (all these countries have had brutal dictatorship suggesting ow the genre serves to offer subversion of dominant narratives). These writers interweave, in an ever-shifting pattern, “a sharply etched realism in representing ordinary events and descriptive details together with fantastic and dreamlike elements, as well as with materials derived from myth and fairy tales” (Abrams). The term magical realism was coined around 1924 by a German art critic named Franz Roh. What he called magical realism was simply painting where real forms are combined in a way that does not conform to reality. He called it an Expressionist painting. (Carpentier). The visual focus of this genre, for this reason, is very significant. Magic realism is closely related to the dreamlike depictions of the expressionist paintings. The Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez was published in 1981. Marquez is known for incorporating this style in his writing. Marquez told the Atlantic in 1973, he wrote magic realism because according to him, that’s just how life was in Latin America. “In Mexico, surrealism runs through the streets.” He was also influenced by the way his grandmother told stories: “She told things that sounded supernatural and fantastic, but she told them with complete naturalness.” This is precisely what magic realism is about. In this genre, one finds the transformation of the common and every day into the awesome and the unreal (Flores). The addition of magical elements to reality is not a forceful intrusion but a seamless blending. The magical elements are normalised and made every day. And sometimes this intrusion is so smooth that it is difficult to recognise. The magical elements are presented as ordinary or matter of fact. There is no sudden surprise. Also, the narrator does not deny or confirm if the magical elements exist or not. In Chronicle of a Death Foretold, there are various instances where the supernatural elements effortlessly blend with the reality to the point that it results in multiple meanings. For instance, Santiago Nasar’s mother is introduced to have a reputation as an interpreter of dreams. The narrator presents this fact as a matter of fact and in a much-normalised way of how the dreams were a reasonable way of interpretation. Later the narrator suggests how the mother has “some medicinal leaves on her temples and the eternal headache”. This reference to the eternal headache is representative of the magical realist elements. This detail is slipped very naturally in the narrative. The narrator even sees Santiago Nasar “in her memory” which could have both supernatural connotations or could symbolically just mean that the narrator saw Nasar through the mother’s perspective. Even Angela Vicario’s confession about her violator uses supernatural elements. “She looked into the shadows…from this world and the other…” The reference to the other world could be of dreams and desires. The shadows could mean supernatural references or simply a reference to her mind. This kind of ambiguity in meaning results from being unable to differentiate between reality and the supernatural which results from the smooth overlapping of the two elements. In magic realism the writer confronts reality and tries to untangle it, to discover what is mysterious in things, in life, in human acts. The principal thing is not the creation of imaginary beings or worlds but the discovery of the mysterious relationship between man and his circumstances (Leal). In Chronicle of a Death Foretold, with the use of magic realism, Marquez tries to question the dominant narrative and bring to view the hidden narrative. This genre is thus suited for political and social critique because it offers a secondary voice. For instance, Angela Vicario’s looking into the “the shadows…from this world and the other…” can be seen as a challenge to the dominant narrative of Santiago Nasar being the culprit. The reference to the other world can be read like the dream world which could represent Angela’s subconscious state of mind which randomly pointed Nasar to be the culprit. Even the bloodlessness of the knives of the Vicario brothers is an unrealistic detail. But this detail seems to suggest how the crime was not just the onus of the brothers but of the whole community. This also mirrors the lack of virginal blood and thus challenges the dominant patriarchal discourse. This bloodlessness could also be indicative of Santiago Nasar’s innocence since personal revenge is seen as justice. There was no physical flowing of blood to prove Angela’s modesty which led to the shedding of the blood of a scapegoat where Santiago is a random victim and the brothers are random criminal. This use of the supernatural element only subtly hints at the possibility of other narratives which could be the actual truth but did not surface because it does not comply with the hegemonic idea. In that sense, magical realist texts ask us to look beyond the limits of the knowable. It is thus truly postmodern in its rejection of the binarisms, rationalisms, and the reductive materialism of Western modernity (Parkinson). Marquez tries to draw this binary with the character of Bayardo San Roman who is mythicized by using supernatural elements. “He looked like a fairy”… “He reminded me of the devil”. He is constantly referred to as strange and mysterious. Legends are created around him which are borrowed from fantastical narratives which are incorporated effortlessly which construct him larger than life. Oral narratives are floated around in the community which idealises him. “It came to be said that he had wiped out villages and sown terror in Casanare as troop commander that he had escaped from Devil’s Island…” This form of mythicization represents Bayardo as the powerful patriarchal outsider whose accusation about the daughter of the community is considered to be the truth. The strangeness and mysterious contributes to this image of the outsider. In that sense, Bayardo San Roman could be the powerful Self which represents the dominant narrative and Santiago Nasar as the weak Other who is sacrificed as a scapegoat to strengthen the narrative of the Self. Furthering the argument, Bayardo San Roman could also be representative of the powerful coloniser who is looked up to and whose discourse becomes the truth. Rushdie sees magic realism as practised by Marquez as a development out of Surrealism that expresses a genuinely Third world consciousness. Magical Realism is different from fantasy writing because the latter deals with the creation of an alternative world whereas magical realism allows a different reality. This is why it is associated with Post-Colonial genres because it allows different cultural reality and questioning of the dominant reality (the voice of the coloniser). Michel Foucault’s theory of the possibility of multiple ‘discourses’ explains how every regime has an official version of the truth and this genre of magic realism questions the official version. It is subversive and destabilizes normative oppositions. The character of Santiago Nasar is of mixed race (half Arabic) and this explains why he must have been framed as the culprit since he is marginalised. The description of Santiago Nasar as a “fleeting passage” (like a ghost) brings in the supernatural element almost creating a mysterious aura around him. His mother is associated with a supernatural ability to interpret dreams. The dreams are spoken to have predictive value, not read using the dominant European Freudian discourse but with respect to cultural beliefs. The presence of the supernatural is often attributed to the primitive or ‘magical’ Indian mentality, which co-exists with European rationality suggesting the conflict between the two worlds: myths and superstition of the American Indians and the European rationalism (Chanady). The wedding as a backdrop is significant for the magic realism genre. It offers a particular sense of subversion which is required for the genre. Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque allows flouting of authority and inversion of social hierarchies which is only possible in the season of a carnival. In the novel, the wedding affects everyone’s rational state of mind and creates a sense of chaos. The theme of magic realism thus offers a sense of subversion and helps in the questioning of dominant discourses which otherwise remain dominant. The smooth narrative of magic realism combines the opposing ideas of magic and realism. This combination suggests how the extraordinary can exist within the ordinary. Marquez creates a world of absolute marvel where he uses the genre to not only create a gripping narrative but also subverts the classical idea of the dominant narrative voice. The whole community becomes guilty and Marquez uses multiple tropes to hint at this idea throughout the text. Thus the genre serves as a critique of the society especially in the context of the Post-Colonial discourse. Works Cited Abrams, M. H. “A Glossary of Literary Terms.” Massachusetts: Earl McPeek, 1999. Carpentier, Alejo. “The Baroque and the Marvellous Real.” Magical Realism. n.d. 102–104. Chanady, Amaryll Beatrice. Magical Realism and the Fantastic Resolved versus Unresolved Antinomy. New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. Flores, Angel. “Magical Realism in Spanish American Fiction.” Magical Realism. n.d. 113–116. Foreman, Gabrielle. “Past on Stories: History and the Magically Real.” Magical Realism. n.d. Leal, Luis. “Magical Realism in Spanish American Fiction.” Magical Realism. n.d. 119–123. Parkinson, Lois. “Magical Romance/Magical Realism: Ghosts in US and Latin American Fiction.” Magical Realism. n.d. 498. https://adibehl01.medium.com/magic-realism-in-the-postcolonial-chronicle-of-a-death-foretold1b0f42942405