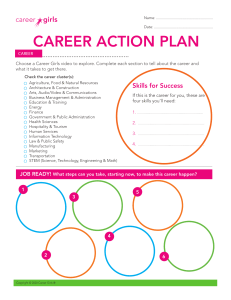

The Communication Review ISSN: 1071-4421 (Print) 1547-7487 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcrv20 Keynote Address: Media, Markets, Gender: Economies of Visibility in a Neoliberal Moment Sarah Banet-Weiser To cite this article: Sarah Banet-Weiser (2015) Keynote Address: Media, Markets, Gender: Economies of Visibility in a Neoliberal Moment, The Communication Review, 18:1, 53-70, DOI: 10.1080/10714421.2015.996398 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2015.996398 Published online: 20 Mar 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3007 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 27 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gcrv20 The Communication Review, 18:53–70, 2015 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1071-4421 print/1547-7487 online DOI: 10.1080/10714421.2015.996398 Keynote Address: Media, Markets, Gender: Economies of Visibility in a Neoliberal Moment SARAH BANET-WEISER Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA This is the keynote address I gave at the Console-ing Passions Conference in April 2014, in Columbia, Missouri. In this talk, I attempted to offer a broad picture of the contemporary gendered economy of visibility and what I am calling the marketing of “empowerment feminism.” It is reproduced here as a talk, without the typical conventions of a scholarly article. A part of it has been published in a special issue of Continuum, Issue 29, Vol. 2, 2015, edited by Amy Dobson and Anita Harris. I want to begin this talk by recognizing the incredible contributions of feminist media scholars who make it possible for me, and many others, to do the work we do. Console-ing Passions, founded in 1989, began as the product of feminist scholars like Julie D’Acci, Jane Feuer, Mary Beth Haralovich, Lauren Rabinowitz, and Lynn Spigel. Other feminist media scholars, such as Angela McRobbie, Jan Radway, Ian Ang, Susan Douglas, Tania Modeleski, Beretta Smith-Shomade, Ellen Seiter, Charlotte Brunsdon, Robin Means Coleman, Anne Balsamo, Mimi White, Michele Hilmes, and many others, recognized the ways in which everyday life—and all media platforms—are gendered, and encouraged us to think about what that means and what are the stakes of acknowledging the gender of everyday routines and practices. These scholars and others formed a theoretical and activist foundation for academics and practitioners all over the world, which is evidenced by all the excellent work presented at the Console-ing Passions conference over the past few days. These scholars also encouraged us to take pleasure seriously, as integral to the formation of identity, as a strategy of empowerment, as activism. For me, McRobbie’s Feminism and Youth Culture (1991), was especially Address correspondence to Sarah Banet-Weiser, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California, 3502 Watt Way, ASC 305, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281. E-mail: sbanet@usc.edu 53 54 S. Banet-Weiser important, as I was writing a dissertation about beauty pageants when it was published and was thinking about how the dominant feminist position on pageants at that time—that they are objectifying, misogynist events, and the women who participate in them are victims of false consciousness—was too sweeping an indictment of women. McRobbie’s work on girls and popular culture (i.e., 1991, 2004, 2009), her call to us to recognize how that which seems to be a clear example of consumption that “plays directly into the hands of corporate consumer culture” (McRobbie, 2009, p. 158) can also be read differently, perhaps as something potentially empowering, was absolutely crucial to my thinking. Indeed, such an insight made it possible for me to write that dissertation and eventually my book (Banet-Weiser, 1999). Perhaps most importantly for me, McRobbie has served as a model for my own thinking about ambivalence and contradiction within cultural spaces and artifacts (Banet-Weiser, 2012). McRobbie’s more recent work has been equally transformative for me: Her ideas about what postfeminism is as a context and an economy, and how dangerous the postfeminist landscape can be for female subjectivity, informs all of my recent work. Yet, when I first read the introduction to her 2009 book, The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture, and Social Change, I was puzzled to read that she sort of rebuked her earlier work, especially the idea of pleasure and ambivalence within consumer culture. As she suggested, she had “misjudged” by attributing “too much hope in the capacity of the world of women’s magazines, to take up and maintain a commitment to feminist issues, encapsulating a kind of popular feminism” (2009, p. 5). I actually don’t think she misjudged (and this might have to do with the fact that I based so much of my dissertation on Feminism and Youth Culture!). I remain invested in her earlier work. But I do think what she is tracing, in the publication of these two books—the first published in 1990, and Aftermath published in 2008—is crucial. This tracing maps a transformative shift in the context in which not only consumption, but also pleasure, takes place. In my own intellectual trajectory, I moved from taking beauty pageants seriously as a space of potential empowerment, to my current work where I look at girl empowerment organizations with a critical eye, especially in terms of the ambivalent spaces they occupy in contemporary culture. It was difficult initially to analyze pageants as complicated and potentially empowering. And, conversely, it is also difficult for me to critique girl empowerment organizations when the stated goal is about enabling girls to be more confident. But the impulse of both these projects is the same: Culture is simply too rich and complex to take at face value, and it is profoundly unproductive to approach a study of culture within binary frameworks. McRobbie’s insistence on this has been my guide throughout my work. The shift in McRobbie’s work maps onto a shift in the structures and infrastructures of the political and cultural economy. Keynote Address 55 In my own work, I see these shifts as one from the politics of visibility to economies of visibility. In my current work, I think through this shift and how it has encouraged an economy of visibility. This shift is not the replacement of one context with another, but rather one that overlaps, with spaces of ambivalence in between. Many feminist media studies scholars have long been invested in studying the politics of visibility. The politics of visibility usually describes the process of making visible a political category (such as gender or race) that is and has been historically marginalized in the media, law, policy, etc. As a politics of visibility, this process describes what is simultaneously a category and a qualifier that can articulate a political identity. Representation, or visibility, takes on a political valence. Here, the goal is that the coupling of the qualifier and “politics” can be productive of something else—hopefully, social change. “Politics,” then, is a descriptor of the practices of visibility, where visibility will hopefully result in political change. In the current environment, however, while the politics of visibility are still important, economies of visibility increasingly structure not just our mediascapes, but our cultural and economic practices and daily lives. Economies of visibility fundamentally transform politics of visibility, because political categories like race and gender have transformed their very logics from the inside out. In turn, political categories have also been restructured and have restructured themselves to stop functioning as qualifiers to politics (and thus no longer being productive of something else). Race and gender, as visibilities, are then self-sufficient, absorbent, and are therefore enough on their own. Economies of visibility do not describe a political process, but rather assume that visibility itself has been absorbed into the economy. The visibility of identities becomes an end in itself, rather than a route to politics (Gray, 2012). Here, economies are different from politics—politics implies a struggle, a recognition of inequity, and most importantly, a highlighting of dynamics of power. Politics references the ways in which systems are structured, and often works to change things at a structural level. So when, for example, media activists challenge networks or other platforms to change representational practices in media, it is done so as a way to change the way identities matter and are valued socially, politically, culturally. Economies, on the other hand, define themselves as sort of neutral; key to most business models, economies exist for the purposes of exchange and most of the time profit. Crucially, economies are about individuals— consumers, buyers, sellers. Economies privilege and give value to the individual within that economy. Economies of visibility are gendered and raced. I focus on girls and women here, because there is a specific imperative for girls and women to make themselves visible in the current moment. They are made more visible not only through media representation and production but also in 56 S. Banet-Weiser discourses of law and policy. Importantly, girls are also widely recognized as one of the most powerful consumer groups in the United States, and are marketed to relentlessly. There is, then, a more demanding imperative for girls and women to be visible, precisely because the bodies of women and girls are always understood as potentialities, in need of regulation and evaluation (see Banet-Weiser, 2013). What do economies of visibility look like? In her 1995 book, American Anatomies, Robyn Wiegman defined “economies of visibility” as “the epistemology of the visual that underlies both race and gender: that process of corporeal inscription that defines each as a binary, wholly visible affair” (1995, p. 8). Wiegman traces this visual inscription of the body historically, in both the pre– and post–Civil Rights eras, and links the economy of visibility to the proliferation of cinema, television and video and the representation of bodies as kinds of commodities. While surely media such as film and television continue to serve up bodies as narrative commodities, I’d like to extend Weigman’s definition to thinking about how economies of visibility work in an era of advanced capitalism and brand culture, postfeminism, and multiple media platforms. Specifically, I see economies of visibility as gendered economies, that function to make the feminine body central, not just in media representation, but also in law, policy, health, and discourses of sexuality. Defining economy in this context is important: On the one hand, I’m not making the argument that we can simply apply a business model onto the ways we construct our personal identities or understand social relations. That is, it is not the case that business strategies get plucked from the realm of economics and mapped neatly onto the realm of culture. Yet, I’m also not using “economy” or “market” as mere metaphors. Rather, I adopt a more nuanced account of the logics and moralities of both economics and culture as a way to understand how identities are constructed within the economy of visibility, and to ask what is at stake in this kind of construction. In particular, what is at stake for girls and women, and for culture, in adopting the logics and moralities of visibility as an end in itself? Every economy comprised different components. For example, as a basic concept, an economy relies on a space wherein forces of supply and demand operate, where buyers and sellers interact to trade or buy goods, where the value of products is deliberated, where consumers are identified, and where specific forms of labor and production occur. The current demand for visibility for girls and women is created in part because girls are seen as in crisis: this most recent “girl crisis” finds purchase in education, self-esteem programs, confidence, and leadership. The supply for visibility takes many forms, but is most clearly enhanced by social media—in an era where selfies are a common form of expression, As Sarah Projansky points out, the demand for visibility for girls is constant: As she says, “media incessantly look at and invite us to look at girls. Girls are Keynote Address 57 objects at which we gaze, whether we want to or not. They are everywhere in our mediascapes. As such, media turn girls into spectacles—visual objects on display” (Projansky, 2014, p. 5). In an economy for visibility, buyers and sellers interact to trade or buy goods. For example, this interaction manifests in YouTube partnerships, where posters can be offered a partnership with YouTube based on the number of hits they have accumulated. It manifests in empowerment organizations, where girls are seen as in need of being empowered, and which use corporate, nonprofit, and governmental funds to form organizations. It manifests in the form of the “girl effect” in international development discourse, where the girl is positioned as the prominent agent of social change and as the symbol for a “smarter economics.” The product in gendered economies of visibility is the feminine body. Its value is constantly deliberated over, evaluated, judged, and scrutinized through media discourses, law, and policy. The dual dynamic of regulating and producing the visible self work to not only serve up bodies as commodities but also create the body and the self as a brand (Banet-Weiser, 2012). Consumers are clearly identified in the economy of visibility. Like with all economies, some consumers are considered more valuable than others (though this does not mean that other sorts of consumers don’t exist). In the economy of visibility, the two most visible female consumers are those that Anita Harris calls “Can-Do girls” and “At-Risk girls” (Harris, 2004). The CanDo girl—typically White, middle class, and entrepreneurial—is positioned in opposition to the At-Risk girl—typically a girl of color or a working class girl, and one who is thus apparently more susceptible to poverty, drugs, early pregnancy, and fewer career goals and ambitions. Defining girls as Can-Do and At-Risk is in part the result of the current historical moment, where girlhood and womanhood is understood as both a site of possibility and a challenge. The visibility of Can-Do and At-Risk girls also creates a context of intense surveillance around girls, a practice of looking that traces their every move to see if it is one on the path to Can-Do or At-Risk. This constant surveillance, in turn, encourages girls’ participation in the circuits of media visibility. And of course, in every economy, there is labor and work. The kind of labor in a specific economy varies. In a gendered economy of visibility, there is a dominant presence of the affective labor of femininity. In a context of post-Fordist capitalism, as many have noted, the content and shape of work shifts, so that work becomes more and more about what Nancy Baym calls “relational labor,” which is “precarious, flexible, immaterial, service-oriented, and often tied to the management of one’s own and others’ emotions.” (Baym, forthcoming; see also Gregg, 2011; Weeks, 2011). Alongside dominant practices of neoliberal capitalism, where work is more “insecure and casualized” (Pratt & Gill, 2008, p. 3), other economies such as 58 S. Banet-Weiser the economy of visibility emerge, where work and labor are primarily selfcare and care work. This is in part because of labor shifts since the 1970s that Lisa Adkins describes as the “cultural feminization of work,” in which, regardless of gender, more workers are expected to incorporate relational work into their routine practices. Here, the labor of the Can-Do girl is especially visible, where girls and young women engage in particular forms of affective labor to make themselves marketable in an economy of visibility. Part of what characterizes the contemporary labor environment is a move away from what have been traditionally more stable jobs (because these jobs are no longer available) toward more precarious, informal ones, where girls and young women cultivate and acquire status as a form of currency, in order to make themselves marketable (Marwick, 2013). Of course, not every girl or woman can monetize their self-work, or their affective labor, in a way that is actually sustaining. The striving for marketability in an economy of visibility functions as what Lauren Berlant calls “cruel optimism,” where affective labor is normative and disciplinary, and works to bind “us into structures and relations that may, in classical Marxist terms, not be in our own real interests” (Berlant, 2011; Pratt & Gill, 2008). Finally, in economies of visibility, there are markets. In the current environment, I see these markets as industries that are built around both the “crisis” of girls and girls as consumers, industries that support and validate the Can-Do girl or invest in the At-Risk girl, that illuminate and make visible specific bodies over others. Again, these are the elements that comprise an economy of visibility: supply and demand, buyers and sellers, deliberation of value, products, consumers, and specific forms of labor and production. Though I laid them out here as separate elements, importantly, they are deeply interrelated and intertwined. In other words, the product in the economy of visibility is the feminine body, but women and girls are also the buyers; the consumers in this economy are also the products. The Can-Do and At-Risk girl can be conflated in the same girl, if one is empowered by her own choices but these choices place her At Risk. The markets for girls exist alongside literal, much more malicious markets in girls. These components are not discrete, but rather inform and constitute each other. In the following talk, I examine two different markets in the economy of visibility: The market for empowerment and the market for protection. THE MARKET FOR EMPOWERMENT In September 2013, New York City unveiled a new public health drive targeted at girls. The program, called the NYC Girls Program, is funded by then Mayor Michael Bloomberg (total cost US$330,000), and includes an afterschool program, physical fitness classes, and a Twitter campaign, #IAmAGirl. Keynote Address 59 The campaign is aimed at “improving girls’ self-esteem and body image,” and features ordinary kids with the tagline: “I’m Beautiful the Way I Am.” The program has a wide distribution plan, with ads on subways and bus stations, and a 30 second video that will be posted on YouTube, the campaign’s website, and played in city taxis. Empowerment is, as we know, a current buzzword—it is the keyword of postfeminism, but it is, and has been, an important term for other kinds of feminism as well; it is a word used relentlessly in marketing and branding; it is a political term, used to capture the need to address disenfranchisement. Because it is so malleable, it lends itself both to politics and commodification. When we talk about empowerment, then, it is crucial to be very specific about what we mean, and we must not simply state it as if it is self-evident. Instead, we must finish the statement with the necessary clause: empowerment for whom? And for what? What are we empowering girls to do? The claim of empowerment by organizations such as the NYC Girls Program is not the same use of empowerment as, say, advertising and marketing (and in the contemporary marketplace, female empowerment is used to sell things from tampons to technology). Yet, the claim of empowerment in girl empowerment organizations rests on a similar foundation as marketing and branding—that of the individual girl, one who is seen to be in crisis and at the same time recognized for her market potential. The NYC Girls Program is part of an exponential rise in “girl empowerment” organizations in the United States, which are variously corporate, nonprofit, and state-funded, in the past 15 years. The Girl Scouts, founded in 1912 and now with 3.2 million members, have more or less held the place of organizations that empower girls in the U.S. While organizations such as the Girl Scouts have long focused on building confidence in young girls, contemporary empowerment organizations and their emphasis on building feminine leadership skills, self-confidence, and healthy self-esteem seem unique to the current context. That is, the contemporary moment is not merely characterized by the commodification of empowerment, but it also positions the subjects of empowerment—girls—as particular kinds of economic subjects. It is, then, not only a process of commodification but a shift in gendered subjectivity. There are different, and contradictory, discourses and practices of femininity that are deeply interrelated in this moment, from a critical focus on the hypersexualization of girls and women in the media, to persistent efforts to empower girls, to postfeminist sex positivity, to the retraction of reproductive rights in the U.S. Girls are generally seen to be “in crisis”—whether because of the media, education, or public policy—and thus are in need of a resolution, found in empowerment organizations. And, since the late 1990s, there has been a remarkable increase in organizations that have the goal of empowering girls. Many of these organizations are well-known, like Girls, Inc. or the Dove Self-Esteem fund. Many others 60 S. Banet-Weiser are smaller and more localized. There are also dozens of empowerment initiatives, such as the recent Sheryl Sandberg’s Ban Bossy campaign and Cover Girl’s #Girls Can. These U.S.-based empowerment organizations emerge at around the same time that empowering girls becomes a central theme in international development discourse. For example, in the mid 2000s, the Nike Foundation, in partnership with the UN and the World Health Organization, coined the term “the Girl Effect,” to demonstrate the significance of empowering girls in a global economy (Koffman & Gill, 2013). Girls have been highlighted by development organizations as “the powerful and privileged agents of social change, indeed even as solutions to the global crisis and world poverty.” (Shain, 2013, p. 9), leading to what Koffman and Gill call the “girl-powering of development” (2013). Investing in girls in this discourse is, importantly, the right business move—it reflects what is called “smarter economics,” where the education of girls in developing nations are seen as the impetus for economic development and progress. Out of over a hundred girl empowerment organizations that have emerged in the U.S. since 1990, 87% have emerged since the late 1990s, with a sharp increase after 2000. Though these organizations all claim to be dedicated to empowering girls, they understand and define empowerment according to different criteria: Those founded in the early 21st–century generally focus on three factors: 40% focus on confidence, leadership, and self-esteem (including those that focus on health and fitness); 37% focus on poverty or risky behaviors (these are mostly international, located in developing countries); 19% focus on the education of specific tools, including media/filmmaking, writing, and STEM fields (Dejmanee, personal correspondence, September 20, 2013). Again, consumers in the economy of visibility are typically Can-Do or At-Risk girls, and the themes of girl empowerment organizations map onto this framework so that those with a focus on confidence, leadership, and self-esteem target the Can-Do girl, while those with a focus on global poverty and education target the At-Risk girl. We first need to think about why there has been such a dramatic increase in these organizations in the 21st century. This increased focus on the empowerment of girls is in part because girls have been identified as a group in “crisis” during this time—in terms of leadership, confidence and education—so that federal and state funding has been allocated to address the problem of girls in education, public discourse, and urban planning; and international development organizations have focused on the girl as the solution to a host of issues, including poverty and the global economy. Another reason there has been such an increase in empowerment organizations within the current moment is because, again, girls are seen as an incredibly lucrative consumer market. They are one of the fastest growing markets in the 21st century, and they are targeted endlessly through branding and marketing culture. Within this multilayered context, girls in crisis and Keynote Address 61 girls as consumers are seen as in need of empowerment. Girls are increasingly positioned within consumer culture as the hopeful solution to tough economic times, and are constantly marketed to because they are seen as financially lucrative. Importantly, these two positionings of girls—as in crisis and as powerful consumers—are mutually sustaining. In both of these subject positions, girls are seen as in need of empowerment, and in both, the definition of empowerment focuses on the individual girl as an entrepreneurial subject. This has allowed for the creation of a market of empowerment. The question that continues to linger, however, is empowerment for what? What are girls empowered to do, exactly? To address these questions, I look at two girl empowerment organizations, the Confidence Coalition, which focuses on confidence and leadership, and AfricAid, which focuses on educating girls in Africa so that they can be part of the official global economy. These two different organizations have different logics and mechanisms—both are nonprofit, but one is geared toward middle-class American girls, and the other geared toward girls in a vastly different economic context, that of global poverty. Without conflating the two contexts, I want to argue that both kinds of organization make visible the two primary consumers in an economy of visibility: the Can-Do and At-Risk girl. THE CONFIDENCE COALITION The Confidence Coalition was founded by the Kappa Delta sorority and, as their mission statement declares, they are dedicated to the “confidence movement” that intends to “build confidence in girls so that they can feel better about themselves, stand up to peer pressure, challenge media stereotypes and bullying behavior, and end abusive relationships.” (Confidence Coalition website) While certainly these are admirable goals, this organization (which is actually a coalition of different organizations) relies on conventional feminine routines, activities, and identities as activist practices. Perhaps most importantly, the Confidence Coalition focuses on the individual girl as an agent for change, thus putting the burden of confidence on her body, rather than addressing more structural and infrastructural mechanisms that encourage a lack of confidence for girls in the first place. Of course, confidence, self-esteem, and leadership are important elements of one’s subjectivity, especially for girls and women who have been encouraged to understand themselves as submissive, insecure, and subordinate. I am not challenging this. But what I am suggesting is that these individual aspects of empowerment lend themselves to commodification, precisely because they are so often expressed and understood within a postfeminist sensibility and a context of capitalist marketability. And, helping girls become more confident in the Confidence Coalition is not a feminist 62 S. Banet-Weiser issue with feminist goals. It is about individual girls and women and their subjectivities, not about the ways patriarchy depends on women being NOT confident. It is this tension, between the important goals of confidence and leadership with girls, and the commodification of these concepts, that then transforms this as an individual rather than a social, or feminist problem. For example, the Confidence Coalition asks girls to take a “pledge to be more confident.” This positions “confidence” as a choice, a commodity—girls, as consumers, just need to be confident, and then apparently it will happen. The various activities endorsed by the Confidence Coalition are typically to be undertaken individually. Their success, measured in terms of self-confidence, is also an individual accomplishment. One of the forms of activism promoted by the Confidence Coalition is the “Go Confidently” handbag collection. This is a campaign where members of the coalition donate handbags, which are then given to charity to give to girls who might not otherwise afford them. While this is not conventional commodity consumption in the sense that it is not a typical purchasing exchange, this campaign challenges little about traditional definitions of femininity as being overly focused on fashion and accessories and the body. More than that, this campaign squarely situates confidence as a commodity— something “you can carry!”—thus relegating empowerment to something that is individual and self-realizing and as part of an industry, instead of recognizing the way that institutionalized gender politics denies power to girls and women. Inserting “empowerment” into industry, or creating it as a kind of market, is not simply marketing spin. There are real stakes in understanding visibility as empowerment. The commodification of empowerment through visibility reifies empowerment as a dynamic force, and contains it as an end in itself, rather than as a starting point for material change and social justice. The “crisis in girls” and the need for confidence achieves momentum within the specific political economy of neoliberal capitalism, where girls are also recognized as important consumers. In fact, the crisis exists as a crisis precisely because there quickly emerged a market for dealing with its needs—which is a key component of the dynamics of neoliberal capitalism. And, as often occurs when markets emerge, the “crisis in girls” was transformed into a brand - a logo or slogan to attach to research reports, self-help books, and educational programs: It is “confidence you can carry!” AFRICAID Alongside those organizations such as the Confidence Coalition that hope to empower can-do girls, a number of non-profit organizations have emerged to help provide resources for those girls who are seen as at-risk. While there are certainly organizations that focus on local marginalized and disenfranchised Keynote Address 63 girls, the majority of groups that have emerged in the 21st century that focus on at-risk girls target those populations affected by global poverty. There is a seeming paradox here, where nonprofit organizations aiming to eradicate global poverty are also built upon the marketability of the “girl crisis,” or at least the ways in which this “crisis” leads to the profitability of girl empowerment in the current economy. So, while “can-do” girls, and the organizations that are created to support and validate this subject position, certainly can be seen as a “value-add” in the marketability of empowerment, the at-risk girls and the organizations that support them are similarly needed as logics for this same market. To be sure, these are different economic contexts, but some of the ways in which they invoke the girl as someone who is both in crisis and a potential economic subject are similar. Thus empowerment organizations often state that the lasting goal of focusing on girls in poverty in international development will be an “investment” in girls, because it is girls who can motivate financial growth. As Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill, Heather Switzer, Farzana Shain, and others have noted, the positioning of girls as the answer to global financial crises has resulted in what Nike has called “the Girl Effect,” where girls are seen as agents of change in development. Take, for example, the empowerment organization AfricAid. The tag line of this U.S. based nonprofit organization is “Reach Teach Empower,” and the mission statement of the group states that it is dedicated to supporting “girls’ education in Africa in order to provide young women with the opportunity to transform their own lives and the futures of their communities” (AfricAid website, my emphasis). Indeed, one event that AfricAid sponsored explicitly references the “Girl Effect:” The primary output of the organization is educational scholarships, with the specific aim “to empower African girls to be leaders.” The organization’s website follows a conventional humanitarian visual aesthetic, with pictures of smiling young African girls at school and at play, as well as an embedded video demonstrating one of the organization’s missions to support girls’ education in Tanzania. But it is not merely the humanitarian narrative that is embodied by organizations such as AfricAid. The narrative focus of empowerment organizations such as the Confidence Coalition on individual issues for girls—i.e., confidence, self-esteem, and body image—is the same narrative that mobilizes organizations that focus on girls who lack resources and are victims of poverty. The Girl Effect, that is, relies on the contrast between girls’ powerlessness and their exceptional capacity (Koffman & Gill, 2013). Within this frame, the Girl Effect, and the organizations that mobilize this discourse, position girls (especially those in the global South), not only as the key to international development but also as the perfect embodiment of a neoliberal subject. Girls in the global South are therefore seen as potential neoliberal subjects, hindered by poverty and patriarchy; they merely have to be harnessed by development organizations in order to realize neoliberal subjectivity. 64 S. Banet-Weiser In fact, it is precisely because of obstacles such as poverty that makes girls in the global South quintessential neoliberal subjects. As Koffman and Gill point out (2013), development initiatives such as the “Girl Effect” portray girls in poverty as “already entrepreneurial” because they have had to be resourceful: “Poverty, it seems, can be celebrated for the entrepreneurial capacities it stimulates” (Koffman and Gill, 2013, p. 90). The “empowerment” message of AfricAid might read a bit differently than the Confidence Coalition, but it still taps into a market of neoliberal empowerment. A postfeminist cultural landscape, neoliberal capitalism, and the normalization of the brand and lifestyle of “girl power” enables these organizations to follow an entrepreneurial business model that is encouraged and given shape by neoliberal capitalist practices, and in both we can see girls as an investment upon which these organizations thrive, and where “empowerment becomes a function of rational exchange.” (Switzer, 2013, p. 349). The goals and intentions of girls’ empowerment organizations are certainly important, and I am not questioning whatever impact they may have here. It is actually quite difficult to be critical of these kinds of organizations. However, it is important to attend to the discourses and practices that provide the logic for these organizations, as they validate the business logic of individual entrepreneurialism and thus have political ramifications for girls’ subjectivities. These are not the same political ramifications that are struggled over within feminist politics. Within the market of empowerment, organizations work to build financial profiles where girls are “human capital investments,” and validate their position as a kind of resolution to financial crisis. THE MARKET FOR PROTECTION There is a seemingly contradictory market emerging at the same time as the market for empowerment: the market for protection. However, these markets are not in opposition to each other, but are rather mutually sustaining. In the market for protection, girls are also seen as “worthy investments.” During the same period when we witness an increase in girl empowerment organizations and the emergence of a market for empowerment, we also see the emergence of another market, what I am calling the market for protection. As I hope to show, both the market for empowerment and protection, while seemingly encompassing different categories of analysis—one is about putting girls on display, the other is about containing girls—revolve around the individual girl and her body. But these markets are recognized as important within an economic context—they are simply “smarter economics” to invest in girls, whether they are Can Do or At Risk. This economic context is not a feminist context—it is not invested in restructuring systems so that Keynote Address 65 girls would not feel insecure in the first place. This lack of feminist politics as a context for empowerment encourages the market for protection, where girls and women are seen as untrustworthy with their personal and bodily choices. The market for protection, unlike the market for empowerment, has clear religious connections, in particular with evangelical culture, because this market focuses on the purity of the female body, and reinforces a religious-patriarchal organization of gender. Here, religion and politics intertwine to create a context that operates under the logics of the neoliberal market, with identifiable consumers, the value of the product—a women’s “purity”—that gets deliberated in public spaces, and an industry of merchandise connected to protecting women. The market for protection has two major components: Abstinence-only education and the purity movement, and the political rollback on women’s rights of the body in the 21st century. ABSTINENCE AND PURITY At the beginning of the 21st century, there was an increase in federal funding of abstinence education at U.S. public schools, and a general increase in the abstinence-until-married movements. Like girl empowerment groups, these initiatives and campaigns range from non-profits to for profit to state-funded. An industry has emerged around these campaigns, including merchandise and retail, public speaking, curriculum services, and literature. While theoretically one could argue that abstinence-only education is targeted to both boys and girls, it is clear that the primary address is to girls, and is focused on the question of “virginity”—a discourse which is almost always applied to girls (Valenti, 2009). Abstinence-only education is not new, but like girls’ empowerment groups, we have seen an exponential rise in these programs in the 21st century. We also see more federal money spent on these programs (while all other sources of federal funding for public school is being cut) in the middle of a global economic recession. The funding amounts have been somewhat uneven, but nonetheless consistent (this can be traced back to the Reagan administration). Federal funding for abstinence only education persists, even given an overwhelming body of research proving that these programs do not work, and that the goals of the federal expenditure have not been achieved. Funding for these programs grew exponentially from 1996 until 2009, particularly during the years of the George W. Bush administration. According to the Sexuality Information and Educational Council of the United States (SEICUS) public policy office, between 1996 and 2009, Congress funneled over one-and-a-half billion tax-payer dollars into abstinence-onlyuntil-marriage programs. While many of the groups are religious-based, there 66 S. Banet-Weiser is also an ostensibly non-religious federal agenda on abstinence only (these are called Welfare Title V, Abstinence till Marriage Fund and SPRANS). In 2010, the Obama administration cut a great deal of the federal money. However, one of the federal funding sources, Title V, was recently resurrected under the Affordable Care Act (which could be read as a way to appease conservatives who were up in arms about the ACA providing coverage for birth control). Importantly, the framing and discourse of Title V has shifted in the 21st century: Unlike other governmental acts that included abstinence education as part of preventing, say, teen pregnancy, the Title V abstinence-only-until-marriage program marked a significant shift in resources and ideology from preventing teen pregnancy to promoting abstinence from sexual activity outside of marriage, at any age. Every state, with the exception of California, has at one time accepted Title V abstinence only-until-marriage funds (and these end up often connected to religious organizations). This shift in rhetoric and ideology from prevention of pregnancy and STDs to preventing all sexual activity before marriage encourages the merging of abstinence-only education with what Jessica Valenti has called the purity movement (Valenti, 2009). Within the market for protection, abstinence-only education and purity discourse position the virginal female body as the product. As in the market for empowerment, consumers within the market for protection are girls and women, who are cast as vulnerable and in-crisis. Here again, girls are seen as worthy investments and important consumers. The investment in girls in the market of protection is about disempowering them through the regulating and policing of their bodies. With identifiable products and consumers, an industry has developed around abstinence and purity, in the form of organizations, speakers for hire, and retail merchandise. These are advertised and offered on a national abstinence clearinghouse website. Organizations such as Aim For Success, True Love Waits, the Pure Love Club, and Project Reality, ask young teens to commit to abstinence until married—and it should be noted that this seems to be an exclusively heteronormative definition of marriage, with many of the organizations defining marriage as “biblical.” For example, the organization True Love Waits asks young teens to make the True Love Waits Pledge: “Believing that true love waits, I make a commitment to God, myself, my family, my friends, my future mate, and my future children to a lifetime of purity including sexual abstinence from this day until the day I enter a biblical marriage relationship.” There are individual speakers for hire; motivational speakers, often comedians, who are hired by schools to present the value of abstinence. A few examples: Jason Evert, from the Pure Love Club, says: “A culture of immodest women will necessarily be a culture of uncommitted men” and “Sexuality is meant to be a gift between a husband and wife for the purpose of babies and bonding.” Justin Lookadoo, a former crime prevention specialist, says about girls: “Accept your girly-ness. You’re a girl. Be proud of all that means. You Keynote Address 67 are soft, you are gentle, you are a woman. Don’t try to be a guy. Guys like you because you are different from them. So let your girly-ness soar.” He also delivers this zinger: “Women shouldn’t be surprised, if they dress like a piece of meat, if men want to put them on the barbeque.” Almost all the speakers on the abstinence clearinghouse site are men, and there is an obvious heteronormativity and misogyny that shapes most of the rhetoric. It is this same discourse that shapes the purity movement: While purity is known as a religious-based movement, there are deeply intertwined relationships between religious purity movement and the federally funded abstinence-only education programs. Retail and merchandise are produced for the purity movement, such as the company, The Silver Ring Thing. This organization seems to revolve around the commodity object: the silver ring that represents one’s pledge to remain a virgin until married. For the Silver Ring Thing, one should only buy and wear the ring after attending a Silver Ring Thing event to discuss purity. They also sell replacement rings (I’m assuming not for people who decided to have sex, but then regretted it), new student ring packages, parent ring packages, and postevent rings for people who attended the events but didn’t have a chance to buy the rings. There are other retailers that are not as overtly religious (such as K-Mart, Target, and Hot Topic) that sell the rings and other purity merchandise alongside other products. Aside from organizations, speakers, and retail, there are other cultural forms associated with purity, such as Purity Balls—which are often federally funded— where young girls pledge their virginity to their fathers at a formal event. Finally, in the market for protection, abstinence and purity exist alongside a more overtly political dimension, the retraction of reproductive rights and other rights of the female body in the U.S. political sphere. At the same time as girl empowerment organizations are gaining traction, there is a parallel political and cultural context in the U.S., where the ostensibly “empowered” female body is under threat. While discourses of visibility and empowerment abound in popular culture and media, in political culture, the bodies of girls and women are increasingly disciplined through law, policy, and public discourse. This disconnect marks the difference between individual empowerment and feminist empowerment; in the first case, with the girls empowerment organizations, the focus is on empowering individual girls (and perhaps by extension, the global economy). While this is important, the focus is not on feminist empowerment. This allows for the market of protection to emerge in particular ways. In the past several years in the U.S., reproductive rights of women have been challenged through a variety of means, from federally funded abstinence programs just discussed to challenges to overturn Roe vs. Wade, to other antiabortion campaigns and restrictions. In 2011 alone, in every state in the U.S., legislators introduced more than 1,100 reproductive health and rights-related provisions. By the end of 2011, 135 of these provisions had 68 S. Banet-Weiser been enacted in 36 states, a dramatic increase from the year before. 68% of these new provisions—92 in 24 states—restrict access to abortion services. These provisions range in severity from conservative discourse trying to prevent health insurance companies to cover contraception to the larger context of public battles over rape and abortion laws. In 2011, for example, more than 200 Republican members of Congress co-sponsored House Resolution 3, the No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion Act, which contained language restricting the exception for federally funded abortions to “an act of forcible rape or, if a minor, an act of incest.” The Tea Party political movement, under the guise of “controlling government spending,” have introduced close to a thousand antiabortion bills in the United States since 2007. These legal struggles have been mirrored in popular and political discourse by the increasing aggressiveness of conservative politicians in making their views on rape and abortion known to the public (as is well known). Last year, at least four states have voted to ban all abortion coverage in private health care plans, Michigan most recently, and most states have limited coverage (more updated stats). The market of empowerment and the market for protection are mutually constitutive and sustaining. They both rely on the female body as product, they both identify girls as primary consumers, and they both deliberate over the cultural value of the body. Yet, the market for empowerment invokes empowerment as an individual characteristic or aspiration, not as a systemic, or feminist, politics of empowerment. The linkage here is that without a feminist definition of empowerment, contradictory markets such as the market for protection can emerge, again focusing on the individual girls body, but in this case as one to be protected. CONCLUSION It is easy to make an argument about these markets as yet another expression of voracious neoliberalism. And it’s easy in part because it is true. But I want to think through the ambivalence of capitalism, and also take seriously what this context enables as well as what it forecloses. In other words, it is important to take seriously the cultural value of emotion, affect, and desire, such as empowerment and confidence, that comes out of capitalist practices, and think about these values in terms of the potential of ambivalence, its generative power. For it is within these spaces that hope and anxiety, pleasure and desire, fear and insecurity are nurtured and maintained. It is here that we can think about what it means to move theory to everyday practice, and how approaching consumer culture, or neoliberalism, for that matter, is not a zero sum game. Investing in girls is important, and significant. But we need to think seriously about the reasons why girls are seen as good investments. It is Keynote Address 69 not necessarily about being fair in an unfair world, or challenging gender inequities that are wide-ranging and systemic. Yet, it is about gender inequality. In 2009, the President of the World Bank said that addressing “gender equality is smart economics.” In Obama’s recent State of the Union Address he said, “When women succeed, America succeeds.” I think we need to think through this, and take this as an opportunity to redefine the discourse here. To return to McRobbie, she argues that girls are seen as better economic subjects in a context in which feminism is losing ground and traction. They are also positioned as better economic subjects within an economy of visibility (McRobbie, 2009). In his recent work, Herman Gray has critiqued visibility, and what he calls the continuing “investment in the cultural politics of representation for the liberal subject of identity” (Gray, 2012). He questions what visibility might mean as a political practice in an era of what he calls “the proliferation of difference,” and he calls this the shift from race to difference. Gray’s focus is on race, specifically African American identity, but I want to think about what this means for gendered identity. That is, the cultural conditions that made it important to demand visibility in the first place—not enough representation, representation that is highly stereotypical, institutionalized sexism—have shifted in an age of postfeminism and advanced capitalism, so that that demand looks different. Rather, the demand for visibility as something that is not coupled with a political project is becoming more and more paramount. This, I see as a shift in how gender is articulated and experienced within an economy of visibility. Here, the shift might be thought of as from liberation to empowerment (Carole Stabile suggested this to me). In a postfeminist context, the historical feminist goals of “liberation” have transformed to empowerment, because ostensibly women and girls have been liberated. That is, liberation, problematic as it is as a concept, was understood within a context of feminism as a way to address structural inequalities. Empowerment is understood within a concept of “smarter economics” that sees gender as an important way to stimulate the economy. Since the connection is economic, the locus of empowerment is the individual girl. This is not unimportant. But like Gray’s concept of difference, empowerment as an individual attribute is both a commodity and a market for commodities. The markets for empowerment and protection are not merely metaphorical markets. Rather, girls are identified as key players in an international market, and we are told to invest in them. But when gender inequality is understood through an economic context rather than a feminist one, we might get smarter economics but not necessarily smarter politics. Both markets rely on the girl’s body as product, both deliberate over the cultural value of girls, and both are situated within an economy of visibility. Feminist politics allows us to question the ways in which these two markets are mutually constitutive, how they inform and validate each other. Feminist politics 70 S. Banet-Weiser insists on wondering why girls should be empowered to feel confident in a context that politically and legally does not trust them to make choices about their own bodies. REFERENCES Banet-Weiser, S. (1999). The most beautiful girl in the world: Beauty pageants and national identity. Berkeley: University of California Press. Banet-Weiser, S. (2012). AuthenticTM : The politics of ambivalence in a brand culture. New York: New York University Press. Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Gill, R. C., & Pratt, C. (2008). In the social factory? Immaterial labour, precariousness and cultural work. Theory, Culture & Society, 25. Gray, H. (2005). Cultural moves: African Americans and the politics of representation. Berkeley: University of California Press. Gregg, M. (2011). Work’s intimacy. London, England: Polity Press. Harris, A. (2004). Future girl: Young women in the twenty-first century. New York, NY: Psychology Press. Koffman, O., & Gill, R. (2013). ‘The revolution will be lead by a 12-year-old girl’: Girl power and global biopolitics. Feminist Review, 105, 83–102. Marwick, A. (2013). Status update: Celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. McRobbie, A. (1991). Feminism and youth culture: from Jackie to Just Seventeen. London, England: Macmillan. McRobbie, A. (2004). Post-feminism and popular culture. Feminist Media Studies, 4, 255–264. McRobbie, A. (2009). The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture and social change. London, England: Sage. Projansky, S. (2014). Spectacular girls: Media fascination and celebrity culture. New York: New York University Press. Shain, F. (2013). ‘The Girl Effect’: Exploring narratives of gendered impacts and opportunities in neoliberal development. Sociological Research Online, 18, 9. Retrieved from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/2/9.html Switzer, H. (2013). (Post) Feminist development fables: The Girl Effect and the production of sexual subjects. Feminist Theory, 14, 345–360. Valenti, J. (2009). The purity myth: How America’s obsession with virginity is hurting young women. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press. Weeks, K. (2011). The problem with work: Feminism, Marxism, antiwork politics and postwork imaginaries. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Wiegman, R. (1995). American anatomies: Theorizing race and gender. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.