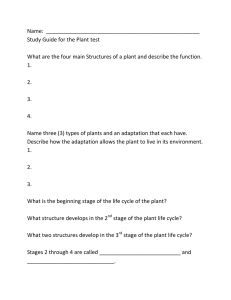

Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Science and Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envsci A framework for analyzing the implementation of climate adaptation policies in the agriculture sector at the subnational level Muhammad Mumtaz a, *, Jose A. Puppim de Oliveira b, 1 a b Department of Public Administration, Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan FGV - Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV EAESP and FGV EBAPE), Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Climate change Adaptation Agriculture Policy implementation Subnational governments Pakistan This study presents a new framework for assessing the effectiveness of the implementation of climate adaptation policies for the agriculture sector at the subnational level. The role of the subnational level in climate policy is highly relevant, especially on the heels of the Paris Agreement (PA) of 2015. However, there is limited literature on climate adaptation policy implementation at the subnational level in the agricultural sector. Climate adap­ tation policy in agriculture is generally discussed at the national level, and subnational climate adaptation policies rarely address agriculture. Thus, this study was conducted to fill this gap by establishing an analytical framework based on the two existing literatures, which are not connected: climate adaptation policies at the subnational level and adaptation policies in the agricultural sector. The core components of the framework are (i) locally driven initiatives, (ii) locally capable institutions, (iii) legally implementable measures, and (iv) effective intergovernmental relations. The framework is then applied to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) and Punjab, two provinces in Pakistan, a country highly dependent on the agricultural sector and one of the most vulnerable to climatic changes. We found that both provinces have locally driven policies and have made efforts to build capabilities in their public administrations to adapt to climate change in the agriculture sector. Punjab has advanced in several indicators of the components of the framework but still is weak in others, such as local monitoring and evaluation efforts. KPK has interesting efforts in the dissemination of farmers’ adaptation innovative initiatives (hidden adaptation), but still lags behind in the legal base for the policies. Finally, both provinces lack strong institutions for intergovernmental relations. 1. Introduction In the last decades, policymakers have attempted to address ’wicked problems’, such as climate change, by engaging stakeholders and different tiers of governance (Wamsler et al., 2020). The complex issue of climate change cannot be solved solely by the national governments without involving various arrangements of state and non-state actors at multiple levels of governance (Tompkins, Adger, 2005; Mumtaz and Ali, 2019). Countries have developed their policies collaboratively by involving non-state actors to address the issue of climate change effec­ tively (Weiss et al., 2013; Weber and Khademian, 2008). In these multi-stakeholder collaborative governance arrangements, the role of subnational governments is recognized as an important agent in effectively delivering public goods and services (Putnam et al., 1994; Savitch, Savitch et al., 2002; Furumo and Lambin, 2020). Subnational levels of government include all levels below the national level, such as provinces and municipalities (OECD, 2012). In this paper, in particular, ’subnational’ means provincial (state) government and local govern­ ments within the domain of provincial government. Many countries have followed the principles of ’localism’ and devolution of power and responsibilities to the subnational governments to strengthen the democratic process and effectively address the com­ plex implementation issues (Evans et al., 2013), which is also valid for climate policies. After the Paris Agreement (PA), subnational govern­ ments are considered the key to the effective implementation of climate policies, particularly adaptation policies. During almost two decades, subnational governments’ role in global climate governance has grown significantly (Bansard et al., 2017). Subnational governments have emerged as influential actors in international climate change policies, particularly through transnational networks (Picavet et al., 2023; * Corresponding author. E-mail address: m.mumtaz@fjwu.edu.pk (M. Mumtaz). 1 ORCID: 0000-0001-5000-6265 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2023.06.002 Received 4 January 2022; Received in revised form 18 March 2023; Accepted 2 June 2023 Available online 15 June 2023 1462-9011/© 2023 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 Macedo et al., 2023). It is normal to find subnational governments leading in innovation in climate policies and shaping climate gover­ nance (Roppongi et al., 2017). Various studies in the existing literature acknowledge the key role subnational climate policies play in global climate governance (Jörgensen, 2011). Moreover, subnational levels serve as laboratories of experimentation, and they could promote policy change through policy learning. In recent years, provincial (sub-national) and locally driven activities for tackling climate change have significantly increased (Qi and Wu, 2013). Subnational governments tended to prioritize mitigation actions (Puppim de Oliveira, 2009) in the past, but they have increas­ ingly got involved in adaptation initiatives more recently. Nevertheless, there are multiple challenges to establishing adapta­ tion policies at the subnational level in certain sectors, such as agricul­ ture, especially in the absence of any comprehensive framework for establishing and implementing climate adaptation policies at the sub­ national level. In the related literature, we could not find any framework to analyze climate change adaptation for the agriculture sector at the subnational level. We used Boolean logic to find the relevant literature using Scopus and the Web of Science (WoS) database (the details of searching the relevant literature are provided in the methodology sec­ tion). In Scopus, we found 1110 articles covering climate change adaptation and the agriculture sector while 33 documents appeared to cover climate change adaptation and subnational search. However, only one research article was found that covers climate change adaptation for agriculture at the subnational level (Shukla et al., 2021). On the other hand, the WoS database identified 1928 articles on climate change adaptation and the agriculture sector. For climate change adaptation and subnational search with Scopus, 31 documents including 30 research articles and one book chapter were found while 31 documents including 30 research articles and a book chapter have emerged on WoS. However, only 4 articles emerged for climate change adaptation at the subnational level in the agriculture sector. There is no such framework proposed in any of these articles. The scarcity of literature limits the understanding of how climate change adaptation for the agriculture sector can be assessed locally. Therefore, this study is conducted to advance the literature on climate adaptation at the subnational level for the agriculture sector by devel­ oping a framework for climate adaptation at the subnational level and applying it empirically. The framework can be used to assess adaptation policies at the subnational level in the agricultural sector in any other country and also be adapted to other economic sectors considering the sector comes under the subnational governmental domain. The next section provides a brief overview of the methodology adopted to develop a framework for the agriculture sector’s climate adaptation at the subnational level. Section three discusses the back­ ground of climate adaptation strategies for the agriculture sector at the subnational level. Section four overviews the implementation challenges for adaptation policies at the subnational level, which is used in section five to develop the established framework of this study. In section six, the proposed framework is applied to the case of Pakistan. Finally, the study ends with a conclusion, final remarks, and suggestions. in the agricultural sector at the national level (Section 3 below) and the literature on climate change adaptation policies at subnational/pro­ vincial level (Section 4 below). As such, the framework (Section 5) is the product of both inductive and deductive reasoning and it is also based on the existing literature on specific observations in the field of the agri­ cultural sector and also confirmed by the interviews. On Scopus, when we searched keywords (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("climate change adaptation") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (agriculture)) and limited the search until December 2022. We found 1408 articles. However, we further limited our search and included only journal articles in the En­ glish language then we found 1110 articles in Scopus. The same was applied in the WoS database, where initially we found 2234 while limiting to journal articles in the English language, and it appeared 1928. Additionally, all abstracts of the extracted articles were reviewed. This approach was only used to find the gaps in the literature and identify the main challenges pointed out by the authors to use in the construction of the framework. We applied a search for climate change adaptation and subnational on both databases to understand how climate change adaptation is studied and investigated at the subnational level. On Scopus, by using keywords (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("climate change adaptation") AND TITLEABS-KEY (subnational)), We found 33 documents comprising 29 research articles and each for a book, book chapters, letters, and a re­ view. However, by utilizing the WoS with the same keywords, we found 31 documents including 30 research articles and a book chapter. We thoroughly read all these documents and systematically reviewed where common challenges of climate change adaptation at subnational were identified and become major components of the framework. We further extended the search and included ’subnational’ in both research databases. Utilizing the Scopus search engine through using keywords (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("climate change adaptation") AND TITLEABS-KEY (agriculture) AND TITLE-ABS KEY (subnational)), we found only one article (Shukla et al., 2021). However, by using the WoS database engine with the same keywords, 4 articles were found (Shukla et al., 2021; Smucker, Nijbroek, 2020; Milhorance et al., 2021; Mil­ horance et al., 2022a,2022b). In the second step, a case study is a proper method to test the framework, as a purely quantitative analysis is not enough to explain a complex phenomenon. Pakistan is a good case to analyze climate adaptation in agriculture because it has prioritized the agriculture sector in its adaptation plans and has given the responsibility to subnational governments (provinces) to develop climate adaptation plans (Vij et al., 2017). The two provinces, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) were selected as two case studies to test the framework developed in the first step because both are involved in interventions to adapt the agriculture sector to climatic change, but they have different approaches. They also differ in terms of the size of the population and agricultural infrastruc­ ture development. These differences allow us to test the framework in diverse institutional contexts. Initially, we collected secondary information through policy docu­ ments including the Punjab Environmental Protection Act 2017, Punjab Climate Change Policy 2017, Punjab Provincial Climate Change Action Plan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Climate Change Policy, Khyber Pak­ htunkhwa Environmental Act 2014, and National Climate Change Policy of Pakistan. Moreover, we used government reports, such as budget allocation reports, and program evaluation reports, such as the climate change profile of Pakistan report of the Asian Development Bank in collaboration with the Pakistani government, Pakistan’s first national communication on climate change, and Pakistan’s second national communication on climate change. Considering the previous steps, the literature reviewed, and research question, semi-structured interviews were carried out with stakeholders keeping in view the components of the proposed framework in two provinces as well as from stakeholders in the national government and other organizations in Islamabad. Information from the interviews was used to triangulate with above mentioned policy documents. Informal 2. Methodology The methodology for this research has two steps. Firstly, a frame­ work is established by reviewing the related literature and identifying the gaps and challenges for implementing climate adaptation policies for the agriculture sector at the subnational level. Secondly, the established framework was applied (Section 6) to assess climate adaptation policies in the agriculture sector in two provinces of Pakistan using the case study as a research method (Ragin and Becker, 1992). In the first step, as the literature on climate change adaptation pol­ icies for the agricultural sector at subnational is limited, the components and subcomponents of the framework are essentially the main chal­ lenges identified by two related literatures: the literature on adaptation 127 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 policy directions from the governmental institutions, such as budget allocation and ad hoc initiatives (e.g., training courses) that may not be part of any policy documents were taken during the interviews in both provinces and were also part of the analysis. Thirty-six in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders from both provinces including governmental officials, members of non-governmental organization, farmers, agriculture extension workers, scientists, media personnel and environmentalists. We developed an interview guide with some leading questions and points of the framework we wanted to have information. Each interview lasted between 60 min and 90 min, and notes were taken, but they were not recorded. Most of the interviews were in English but some were in Urdu, especially with farmers. These interviews were done during first fieldwork research between November 2016 and April 2017, with follow-up interviews between 2019 and 2022, 3 informal interviews were conducted with the experts on the findings of the study. In the first fieldwork phase, six exploratory interviews were conducted in Pakistan with government officials and policy experts to understand the broad perspectives of climate change adaptation in the respective provinces and the national level. The interviews were analyzed and codified to identify the indicators’ implementation level in the four components identified in the framework (in Section 5 and Fig. 1). After the in­ terviews were completed, the interview notes and key observations were reviewed, codified, and summarized using the interview guide and translated into English if they were in Urdu. The list of respondents is given in Appendix-A. The interviews also helped to confirm the frame­ work’s components specified in the literature. 3. Climate adaptation strategies for the agriculture sector Climate-related risks affect agricultural development and manage­ ment. Climate change poses negative impacts on the agriculture sector and destabilizes the livelihoods of smallholders and farmers at the local level (Below et al., 2010). Climatic change impacts crop productivity Fig. 1. Proposed Framework of the Study Source: developed by the authors. 128 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 and local farmers’ ability to agricultural produce. It has been identified that almost 70% of people in developing countries live in rural areas where agriculture is the main livelihood and the agriculture sector is highly at risk due to the adverse impacts of climate change (Vermeulen et al., 2012). Uncertainties in climate change scenarios make it difficult to deter­ mine the precise impacts on future agricultural productivity. However, food security challenges are growing, and the situation will be worse by 2050 if the proper actions are not taken to adapt the agriculture sector to the future climate scenarios. Various studies have identified that sig­ nificant losses in the agriculture sector should be expected worldwide (Nelson et al., 2008). It is widely acknowledged that policies need to provide a supportive environment that guides governments in planning and executing adaptation interventions and enables farming commu­ nities to adapt to climate change (Berman et al., 2015). There is a growing consensus that local knowledge is important for effective adaptation (Mertz et al., 2009). Although the local farmers’ communities are adapting their agriculture practices to the changing climate (Knox et al., 2012), they are still vulnerable to climate change and variability (Ali and Erenstein, 2017). Local knowledge can play a promising role in addressing the challenges of climate change at the local scale for the agriculture sector. It is imperative to focus on framing local policies and plans to enhance public awareness regarding climate change risks and understand the significance of climate adaptation (Aslam and Rana, 2022). Local knowledge is based on practice and as­ sists farmers in making informed decisions about how to respond to environmental changes and how to improve the amount and quality of their yield (Newsham and Thomas, 2011). Farmers’ local knowledge has proved very useful for enhancing their adaptive capacity and designing climate adaptation policies (Mumtaz and Puppim de Oliveira, 2019). However, there is a lack of evidence in the literature to study local knowledge as a reflection of climate variability, its effects, and adap­ tations in agriculture (Ogalleh et al., 2012). Researchers, farmers’ communities, and government officials worldwide recognize that climate change adaptation is a priority issue for climate change (Soubry, 2017). But how can this be done most effectively? One of the biggest challenges is the need for climate change adaptation solutions to be context-specific (Soubry, 2017). A one size fits all approach to policy does not work, as climate, soil, and farming cul­ ture differ from place to place. This has led many to the conclusion that local participatory approaches to adaptation planning and building adaptive capacity should be encouraged. Therefore, considering the implications of climate change to the farmers and the agriculture sector, the voices in the local context are highly valuable. Agriculture has al­ ways adapted to the climate, with regionally specific adapted systems being observed worldwide (Ren et al., 2014; Singh and Singh, 2017). The adaptation policies towards the agriculture sector have to be based on how the local farmers understand climate-related risks and respond to those risks (Niles et al., 2013), together with other strategies. To effectively address the challenges for the agriculture sector, the concept of Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) was introduced. The CSA can be defined as an approach to transforming and reorienting agri­ cultural development under the new realities of climate change (Lipper et al., 2014). Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) defines the CSA as ’agriculture that sustainably increases productivity, enhances resilience (adaptation), reduces/removes GHGs (mitigation) where possible, and enhances achievement of national food security and development goals’ (FAO, 2013). Lipper et al. (2014) further identified that productivity, adaptation, and mitigations are critical for achieving this goal. Adaptation in the case of the CSA is utilized by reducing farmers’ exposure to short-term risks and strengthening their resilience by building their capacity to adapt and face long-term challenges. Particular attention is given to protecting the ecosystems that provide services to farmers and others. These services are essential for maintaining productivity and our ability to adapt to climatic changes. However, there is a need to have a proper set-up at the local scale to materialize the concept of the CSA. Here subnational governments have an important role in establishing better adaptation policies and action plans to ensure the implementation of the CSA mission. Scale up the CSA triggered to establish supportive agricultural pol­ icies, institutions, and financing at a different level of governance (Westermann et al., 2015). However, these responses depend on the information and socio-economic condition of the local farmers. For example, poor farmers ensure their survival, but wealthier farmers make decisions to enhance their productivity and maximize profits (Ziervogel et al., 2006). Various initiatives on climate adaptation towards the agriculture sector at different levels of government are taking place in the world depending on the nature of governance in a particular country (Zier­ vogel et al., 2006). Literature on adaptation measures to address climate change for the agriculture sector, such as (Clar and Steurer, 2019; Neset et al., 2019; Cattivelli, 2021), identified diverse initiatives are in effect depending on the regional and/or national conditions. Various conditions are pointed out in the literature for the effec­ tiveness of adaptation actions (Wise et al., 2014). These conditions are in the form of providing reasonable financial capacity and proper infor­ mation systems. Applicable technologies are also considered a contrib­ uting aspect to producing robust policies and implementing adaptation measures. Moreover, proper infrastructure, committed institutions, and an equity system can be helpful for effective adaptation actions. These important aspects of adaptation are considered the components of adaptive capacity (Oberlack and Eisenack, 2014). Adaptation literature dictates that sometimes adaptation measures are implemented with no or low costs (Rojas-Downing et al., 2017). However, in most cases, for the implementation of adaptation measures, there are costs or upfront investments (Hallegatte, 2009). Our search in the relevant literature shows a lack of evidence to explain how climate adaptation policies for agriculture at the subnational level are established and how they are implemented. The literature only emphasizes the importance of local climate adaptation strategies but clearly lacks how it should be done (Vij et al., 2017). To fill this gap, this study is conducted to develop a framework and bring evidence from the case of Pakistan. Climate change adaptation is mainly a local issue, especially in the agricultural sector (Kassie et al., 2015). Kassie et al. (2015) further argued that local government institutions such as provinces, districts, and municipalities know the need for adaptation strategies. These local institutions have comparatively better knowledge and ideas to deal with climate crises in all sectors, including agriculture (Mumtaz, 2021). However, there are challenges to establishing and operationalizing climate adaptation policies effectively in the agriculture sector at the local level. These challenges mainly include a weak capacity of in­ stitutions, an absence of local actors in policy framing, a lack of connection in intergovernmental relations, and a weak legal system (Mumtaz and Ali, 2019). Keeping in view the challenges for establishing climate adaptation policies for the agriculture sector and implementa­ tion gaps in these policies, we examine those gaps in light of the climate change adaptation literature at the subnational level. We map the po­ tential challenges for implementation (Section 4) and propose a frame­ work (Section 5) that can assess how effective climate adaptation policies are devised and implemented at the subnational/provincial level. 4. Mapping the implementation challenges for adaptation policies at the subnational level Effective actions through local and other subnational governments can bring significant results to address the challenges of climate change and its impacts on different sectors, including agriculture (Dawson, 2007). However, although progress has been made in developing a governance system for climate change adaptation at the local level, there are still multiple challenges, especially at the implementation 129 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 stage, due to a lack of harmonized sectoral and local planning systems (Madzwamuse, 2010; Mumtaz et al., 2019). As discussed in the previous section, various studies have suggested strategies for meeting the chal­ lenges of climatic impacts on the agriculture sector, but mostly at the national or international level. Thus, an analytical framework to un­ derstand how best adaptation policies at the subnational level can be developed and how best these policies work for the agriculture sector bringing together the two literatures (subnational adaptation policies and adaptation policies in the agricultural sector). Local adaptation policies for the agriculture sector are important because local governments are closer to local farmers and better posi­ tioned to adjust to changing climate (Mumtaz, 2023). As the climatic impacts are essentially local, adequate governance responses are required by individuals and communities locally (Adger, Kelly, 1999). As a result, the process of adaptation is strongly influenced by local contexts; choices and collective actions are impactful if taken by the local actors and institutions (Tanner et al., 2009). The international community focuses on long-term adaptation strategies by emphasizing local adaptation strategies in national development plans and policies (Hardee and Mutunga, 2010). Likewise, Yamin et al. (2005) argued an operational framework that links locally determined adaptation is needed with national and international policy. Local and regional planning and policy can play a major role in developing local farmers’ capacity and providing tools to support communities in their endeavors to tackle climate change as per local requirements (Mubaya et al., 2012). However, the literature identified some of the main challenges faced by subnational governments to develop and implement adaptation policies. These challenges have been identified by following a codifying process by organizing the research articles in common themes from the sys­ tematic literature review and triangulated with the opinions of in­ terviewers. The detailed process of identification of these challenges and establishing the framework components have been explained in the methodology section. These challenges are described below effectively: a) Lack of involvement of local actors is a real challenge for imple­ menting climate adaptation policies at the subnational level (Puppim de Oliveira, 2009). It is important to listen to the voices of local actors in policy framing and consider them as key stakeholders in implementing adaptation policies at the subnational level, especially in the agriculture sector, as they can bring knowledge and resources. The involvement of local actors in the early stages of the policy process brings support for policy implementation (Puppim de Oliveira, 2005). However, a study on local adaptation planning identifies that the local level has not been sufficiently involved in adaptation policy planning, thus resulting in a challenge in implementing such policies (Dhungana et al., 2017). Non-consultative policy processes at the local scale always pose a serious challenge to effective policy implementation (Pinto and Puppim de Oliveira, 2008). These local and non-state actors are fundamental to designing and implementing climate change actions at the local level (Bulkeley et al., 2009). In the case of adaptation policies for the agri­ culture sector, local farmers and their traditional knowledge are needed to shape subnational climate policies. These local actors and institutions are also essentially important for implementing these policies. b) Local institutions are critical for handling climate change impacts at the subnational level, but many places, especially developing countries, lack effective institutions at the subnational level. Subnational govern­ ments often do not have the institutional capacity or considerable financial resources necessary for taking climate change actions, espe­ cially adaptation measures (Mukheibir and Ziervogel, 2007). The weak local institutional arrangement, lack of infrastructure, scarcity of financial resources, and lack of proper involvement of local actors are the major barriers to the limited adaptation activities (Tiwari et al., 2014). The capability of local institutions can be enhanced by involving the local actors in the whole policy process while establishing adapta­ tion policies and action plans (Sumra et al., 2020; Kehler and Birchall, 2023). The capacity of subnational governments to deal with climate change may be strengthened by the participation of other subnational governments, civil society groups, NGOs, and the private sector. c) Absence of laws and litigation are other challenges to implementing policies at a local level (Setzer and Vanhala, 2019). Proper laws and litigation systems are key for any policy implementation, as many dis­ putes may emerge in the process. Legal and regulatory instruments or binding regulations require "actors to act within clearly defined boundaries of what is allowed and what is not " (Borrás and Edquist, 2013). Institutional stability, which can be brought through legal backing, is a driver to deliver intended actions, thus, making subnational policies effective or impactful (Anderton and Setzer, 2018). It is argued that [state and local] laws’ help to move the dialogue on climate regu­ lation forward’ (Osofsky, 2007). Laws and regulations for taking actions make the institutions and local actors accountable, and more impactful results can be achieved at the subnational level, fulfilling the one important legal aspect raised by Termeer et al. (2011). For instance, in cases where laws are not enforced, these instruments are typically backed by the threat of sanctions, such as fines or withdrawal of rights that also support some level of implementation. Thus, legal and regu­ latory instruments play a normative role in helping some actions and identifying them as acceptable, as well as further providing possibilities for sanctioning non-compliance (Herath and Rao, 2009). Therefore, legal backing for climate adaptation policies is an important prerequisite for successfully implementing policies at the subnational level. d) Inadequate institutional coordination is another major challenge for taking concrete actions and poses a threat to the proper implementation of adaptation policies at the subnational level. Weak institutional co­ ordination among governments is a major factor in the lack of effective climate change policies at a local scale. Policymakers worldwide have now recognized the necessity of integrating adaptive thinking in rele­ vant areas of public policy-making across different levels of governance (Urwin and Jordan, 2008). It is suggested that horizontal and vertical coordination and the combination of top-down and bottom-up ap­ proaches are the focus of adaptation policies to attain effective adap­ tation measures (Dessai and Hulme, 2004). The weak coordination between the national governments, states, and local authorities con­ tributes to inefficient implementation efforts of climate policies at a local level (Setzer, 2013). Thus, even though climate change is a global challenge, international and national efforts need to bring capability and financial resources to subnational governments and extend their help to the most vulnerable communities in the world, many of which rely on the agriculture sector. Facilitation and financial and technical support from developed coun­ tries and international organizations are effective by establishing a regular and proper linkage with subnational governments (Bodansky et al., 2014). Therefore, it is very important for subnational governments to have coordination mechanisms with institutions at the local, national, and international levels. 5. Proposed framework of the study Drawing from the literature on the challenges for climate adaptation at the subnational level above (Section 4), which were reflected for the agricultural sector, a framework to assess those challenges is developed as pictured in Fig. 1. Four main components were identified as necessary for addressing each of the four challenges fostering climate change adaptation at the subnational level in the agriculture sector: locally driven, institutionally capable, legally stable, and cooperative in inter­ governmental relations. Each component is formed by indicators iden­ tified in the implementation literature that can be qualitatively assessed (inside the circles in Fig. 1). 5.1. Locally driven Related institutions and local governance processes are important components for establishing a climate change policy at the subnational level and for its effective implementation (Pervin et al., 2013). 130 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 Collective efforts are key for good adaptive governance at the sub­ national/local level. Effective stakeholder engagement is necessary to plan climate policies, particularly for collective actions and facilitating social learning (Preston, 2013). The interaction among local farmers is strongly encouraged for effective climate adaptation (Muench et al., 2021). Adger et al. (2005) suggested that successful adaptation should balance efficiency, effectiveness, equity, and legitimacy. Our analysis based on the literature and interviews find that local institutions and involvement of all related stakeholders, such as local farmers, local media, agriculture extension departments, academics working on agri­ culture, and local and international NGOs, are important components for effective adaptive climate governance at a local level. Local actions through local actors are important in mainstreaming climate adaptation, especially for the agriculture sector (Nkiaka and Lovett, 2018). Moni­ toring and evaluation are key for effective climate adaptation actions at the subnational and local levels. Pradhan et al. (2017) suggested that the effectiveness of a policy is accessed through a proper evaluation mech­ anism so that any weak aspects can be identified and it can be addressed in due course of time. envisions that subnational entities are the main actors in global gover­ nance in their own right (Andonova and Mitchell, 2010). In climate legal governance, subnational governments can promulgate laws and new regulations to manage sectoral (including agriculture) challenges without regulations at the national and international levels (Michaelowa and Michaelowa, 2017). After the Paris Agreement (PA), the efforts of subnational govern­ ments have been strengthened, and they have different options to continue establishing climate-related commitments and engaging internationally (Allain-Dupré, 2011). After this transformation of governance structure, legislation regulating the agriculture sector at the subnational and local levels emerged (Thrän et al., 2020). Such inter­ national laws turning into local regulation by the subnational govern­ ments and backing local policies by international organizations are considered positive features of polycentric governance (Mearns et al., 2009). Therefore, subnational governments have an important mandate to legislate in the local context so that effective climate actions and implementation of global policies and international laws can be rein­ forced, particularly in the agricultural domain. Creating stable in­ stitutions and improving transparency and financial stability not only set rules of operation but also contributes to developing countries’ ac­ cess to international climate finance. Legislation lends credibility to governments’ commitments, making international agreements more likely and meaningful (Averchenkova and Bassi, 2016). 5.2. Institutionally capable Many studies have argued that scientific research, information net­ works, and capacity-building are prerequisites for effective climate change adaptation governance (Fünfgeld, 2015). Nkiaka and Lovett (2018) proposed that institutional arrangement is key to facilitating climate adaptation into sectoral policies, such as agriculture which is a key sector impacted by climate change (Mumtaz et al., 2019). Promoting research and innovation can be encouraged locally, for example, by involving local educational institutions focusing on agricultural educa­ tion. The involvement of these local institutions helps to uncover the climatic impacts on various sectors, including the agriculture sector. It will also provide novel, implementable, and acceptable solutions at the subnational level. Therefore, research and innovation in localized educational institutions are key for effective climate adaptation policies and governance for the agriculture sector at the subnational level. Effective agricultural policies and active agricultural extension de­ partments can be used to implement such policies at the subnational level in a better way. However, it has been seen that these institutions are generally weak to contribute while managing climate change in a local context, especially in the case of developing countries (Agrawal, 2010). Capability building can be improved by defining a task with proper responsibility, establishing a proper mechanism of coordination among the local institutions, and networking with national and inter­ national organizations, particularly those working towards climate change adaptation and agriculture. Climate adaptation actions require a considerable budget for local agriculture institutions. Allocation of a reasonable financial budget for climate actions is always needed. The lack of finances is a challenge for proper planning, which requires additional budgets for more climate-resilient development. 5.4. Intergovernmental relations Intergovernmental relations are critical to devise and implement public policies, especially when multi-sectorial approaches are involved (Urwin and Jordan, 2008). The adaptation literature argues that lack of coordination among the government units is the real challenge for the weak implementation of climate adaptation policies at the subnational level (Prasad and Sud, 2019; Vij et al., 2017). Some important studies, such as Njuguna et al. (2022), emphasized intergovernmental relations’ role in adaptation to climate change and establishing proper plans. Moreover, relations between policy actors (elected officials) and public administration (employed to implement policies and serve the govern­ ment of the day) must be strengthened (Alford et al., 2017). Thus, intergovernmental relations are key for establishing and implementing climate adaptation policies at the subnational level in agriculture, as adaptation requires efforts from different levels of governance. Multiple stakeholders and multisector interests are involved in agriculture such as forests, energy, water, and revenue and land de­ partments. However, inconsistencies between national and local adap­ tation policies and strategies exist (Zhao and Li, 2015). There is a need for integration and coordination to enhance the ability to adapt to climate change at a national, regional, and local level (Tonmoy et al., 2020). In many instances, local-level governments require support from the other tiers of government for better communication and coordina­ tion of the responses and resources (Birchall and Kehler, 2023). For example, the national government can provide technical and financial support for agricultural extension departments to improve their capa­ bilities. It has been seen that the agricultural departments and related institutions at the subnational level, especially in developing countries, are facing severe challenges in terms of technical and financial capa­ bilities while facing climate change (Huntjens et al., 2012). Therefore, the mobilization of such resources at the national level can help and facilitate local agricultural institutions to effectively address the chal­ lenge of climate change. In the next section, we apply the framework based on the four components and their indicators identified in the literature above to assess the effectiveness of climate change adaptation in the agriculture sector in two Pakistani Provinces. 5.3. Legally strong Legal aspects are important to devise climate measures, especially for implementing climate adaptation policies for the agriculture sector, as laws can provide a stable environment for investing time and resources. During the last two decades, legislation has been developed to promote climate actions and implement climate policies around the world (Lachapelle and Paterson, 2013). Laws create institutional arrangements that define responsibilities for actors in every sector, including the agriculture sector, to act as per their defined mandate (Crouch et al., 2007). On the heels of the governance structure shift from national to sub­ national, local governments have become key players in enacting legislation. In the environmental and climate contexts, this shift 131 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 policy measures to curb climate change, especially for agriculture. This study assesses the policy responses and applies the analytical framework in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) (see map in Fig. 2). Punjab is the second largest and most populous province in Pakistan. The province accounts for 57% of the total cultivated land and 69% of the total cropped area of Pakistan (Mahmood et al., 2016). It has about 57% of agricultural land and contributes 53% of Pakistan’s agricultural GDP (Hanif et al., 2010). The KPK is formerly named North West Frontier Province and has suffered heavily from natural climate disasters. Climate change is posing adverse impacts on agricultural productivity throughout the KPK. It was one of the most affected regions by the megafloods in 2010. Thus climate change has had a significant social and economic impact, as agriculture is the major livelihood of the people in the province. The agriculture sector contributes 48% of the total labor force and 40% to the GDP of the province (Khan, 2012). The established framework to assess the effectiveness of the imple­ mentation of adaptation policies at the subnational level in the previous sections (see Fig. 1) is applied in KPK and Punjab based on the material collected in the fieldwork and reflecting the year 2020. Table 1 indicates the results of our study. The levels of achievement of each indicator were identified after the analysis of policy documents and checked during the interviews in light of the established framework. The indicator achievement is marked as High Level (√√√), Medium Level (√√), and Low Level (√). High-level achievement means the initiative is fully operational, and an external evaluator can confirm it. The impacts of the implemented measures can also be observed. Medium-level achieve­ ment means some initiatives are partially implemented and moving in the right direction. These initiatives effects can be witnessed, but they have yet to lead to significant impacts. Low-level achievement means the initiatives in that component are at a very basic level of results, but the subnational governments are committed to implementing them. The full details of the criteria for each indicator are given in Appendix B. The assessment in Table 1 shows that both provinces have locally driven policies and have made efforts to build capabilities in their public administrations to adapt to climate change in the agriculture sector. Despite the advancements in Punjab, KPK still lags in the legal base for the policies. Finally, both provinces lack strong institutions for 6. Application of the framework in the Pakistani case Pakistan is ranked in the list of top 10 countries that are the most vulnerable to climate change (Faisal et al., 2020). As a result, policy responses of Pakistan are more focused on adaptation actions (Vij et al., 2017; Mumtaz and Ali, 2019; Mumtaz, 2021). After the 18th constitu­ tional amendment in 2010 in Pakistan, provinces/subnational govern­ ments are responsible for establishing and implementing climate change policies. The country has taken multiple initiatives for climate change adaptation at the federal level and at provincial levels. In this context, the agriculture sector is the backbone of the economy of Pakistan. It is considered the major sector for the country’s climate change policies and action plans. Pakistan is an agriculture-dependent country; almost 45% percent of the country’s labor force is in this sector (Rehman et al., 2015). Agriculture sector contributes to about 21.4% of Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP). Furthermore, about 60% of the country’s exports are dependent on the agriculture sector in Pakistan, which puts the economy under threat due to the negative impacts of climate change (Hanif et al., 2010). Considering the size of the agriculture sector to the rural livelihoods and Pakistan’s economy, the significance of adaptation strategies towards climate change is fundamental (Ali and Erenstein, 2017). At the federal level, the Ministry of Climate Change (MoCC) is the central body responsible for dealing with all climate change-related activities at the international level and establishing a coordination mechanism among the subnational/provincial governments. It also oversees the implementation progress of the provinces by regularly ar­ ranging meetings with them. According to Pakistan’s MoCC, "The min­ istry also deals with other countries, international agencies, and forums for coordination, monitoring, and implementation of environmental agreements." In 2017, Pakistan passed the climate change act 2017. With this act, three important institutions were established to improve climate change governance in the country further: the Pakistan Climate Change Council, the Pakistan Climate Change Authority, and the Pakistan Climate Change Fund. However, the formulation and imple­ mentation of climate policies are the responsibilities of the provincial governments in Pakistan. Subnational governments in Pakistan have taken several adaptation Fig. 2. Map of Pakistan. This map is taken from an Internet website. (http://www.maps-of-the-world.net/maps-of-asia/maps-of-pakistan/). 132 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 allocated to address the issue of climate change as it faces huge impacts like recurrent floods, heat waves, cyclones, drought, desertification, glacial melt, and sea level rise despite its minimal contribution to global warming. The KPK government has allocated a budget for climaterelated activities at the provincial level. This budget is almost 8% of the total developmental budget of the province (directly related to economic and social development such as education, health, social welfare, rural development, and scientific research). Similarly, in Pun­ jab, in 2015–17, the government allocated 20% of its budget to climate change-related projects in its public sector development program (Oxfam and Consortium, 2017). Laws and regulations are important to ensure the implementation of climate adaptation policies at any level of governance in the country. Pakistan passed the climate change act in 2017 and became one of the few countries that have passed such acts. The provincial governments in Pakistan have to coordinate their legal apparatus with this act. Punjab has established some laws in the form of the Punjab Environmental Protection Act, 1997 (No. XXXIV of 1997) (Amended 2012) and the Punjab Environmental Protection (Amendment) Act 2017-(Act XIX of 2017) to comply with climate change act 2017 while no such law enacted in the KPK in recent past adjusting with the 2017 act. However, both provinces need to work better in providing legal backing for accountability and transparency in implementing climate adaptation policies. Intergovernmental relations are essential for formulating and implementing climate adaptation policies at the subnational and local levels. We found that the intergovernmental relations in the KPK are weak while Punjab province is performing better in these relations but still lacking the strength to generate good support for climate adapta­ tion. The local institutions in KPK do not know much about the exact scope of each other work towards climate change but in the case of Punjab, the local institutions are closely connected, but they are familiar with the work of each other. Likewise, the respondent from the climate change center in KPK did not know about all the details of the MoCC due to weak vertical coordination. At the same time, the Punjab case appeared much more collaborative and was found effective in coordi­ nation with the MoCC. Government tenure (2013–2018), and political parties in federal and provincial governments were the same in Punjab and different in KPK. It is challenging to produce better intergovern­ mental relations when various political parties have different manifestos and governing approaches at the federal and provincial levels (Puppim de Oliveira, 2019). It is equally important to cooperate and work in line with international efforts to curb climate change. We noticed that it has yet to establish effective relations with international organizations in both provinces. For example, Pakistan has failed to secure large amounts of funds for climate adaptation from international donors, despite Pakistan being one of the most vulnerable countries. Asian Development Bank has provided a fund of $13.9 million, the Adaptation Fund (around $31.7 million), and the Fast Start Finance (around $31.7 million) for climate adaptation (Chaudhry, 2017). However, these are not sufficient funds, considering the vulnerability to climate change of the country. Table 1 Assessment of adaptation policies in Punjab and in the KPK. Component of proposed framework Indicators for the components of the proposed framework Achievements In KPK Achievements In Punjab Locally Driven Engagement of local actors Incorporation of hidden adaptation Research and innovation at Local academic institutions Locally Monitoring and Evaluation Local Institutionalization Institutional mechanism of coordination Allocation of financial budget Legal backing for implementing policies Legally accountability and transparency National, Subnational, and local-level institutional linkages Incorporation of International efforts √√ √√√ √√√ √√ √√ √√√ √ √ √√ √√ √√ √√ √√ √√ √ √√ √ √√ √ √√ √ √ Institutionally Capable Legally Strong Intergovernmental institutions relations intergovernmental relations. Both subnational governments have been keen to involve local actors in establishing adaptation action plans for the agriculture sector. For example, in 2015, the Punjab government launched a very compre­ hensive awareness campaign about climate change in local media, active involvement of agriculture extension departments, arrangement of various training programs for farmers, the establishment of various research centers across the province to measure or to quantify the im­ pacts of climate change on the agriculture sector. KPK is noted to be less effective in involving all the related stakeholders. However, KPK prov­ ince is found ahead in identifying new ways of adaptation in the form of hidden adaptation, i.e., initiatives emerging from the farmers based on their local knowledge and disseminating these initiatives to other areas. Without involving academics and research, and innovation, Punjab is reported ahead of KPK, as the province is much more resourceful in terms of research institutions in the agricultural sector. For example, in Punjab, the local farmers have changed their perceptions of climate change’s negative impacts as previously, the negative effects of climate change were considered a natural phenomenon. However, based on research-based evidence and conducting studies in local areas in the province, the farmers have changed their perceptions about climatic impacts. Proper monitoring and evaluation mechanisms at the local scales are lacking in both provinces. The capacity of local institutions in both provinces is not up to mark as the responsibility of implementing these policies came on their shoulders in 2010 after the 18th constitutional amendment. As per the rating of the proposed framework, both lies at a medium level in term of the capacities of local institutions. It may take time to develop the ca­ pacity of local institutions in both provinces. It is found that overall weak coordination among the local institutions is observed in the KPK and comparatively better in Punjab. For instance, there is no formal and regular interactions or institutional mechanism to discuss climate change issues among the local institutions in KPK. In Punjab, all 26 organizations related to climate change not only meet regularly but are highly familiar with the work scope of each other. The budget is being 7. Conclusion and final remarks Climate change adaptation is a new policy field and created a space for experimentation and new forms of governance. It is important to introduce new frameworks to study adaptive governance in different sectors and produce field base research studies to understand climate adaptation governance better. This paper established a framework for the formulation and implementation of climate adaptation policies for the agriculture sector at the subnational level. Based on the literature and confirmed in the analysis of the interviews, the important compo­ nents of this framework were defined as locally driven initiatives, capable local institutions, legally backing implementation, and proper intergovernmental coordination. Local responses to climate change are driving factors for climate adaptation governance. The success and 133 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 failure of an adaptive form of governance highly depend on local governance actions. In our case study, while applying the established framework based on the four components and their indicators, we identified important steps taken by the two provinces, such as the establishment of the provincial climate change policies in both prov­ inces, institutional capacity enhancement in Punjab, the establishment of linkage with academics in Punjab, involvement of farmers’ commu­ nity in climate adaptation for agriculture sectors in KPK and steps taken towards enhancement of capacity building in both provinces. Multiple stakeholders are involved in climate change governance at subnational levels in both provinces. Political leadership is active, especially in the KPK, to promote sound and sustainable steps to address climate change in the province. However, there is no such effective monitoring mech­ anism, and evaluation was observed in both provinces. The proposed framework can be further developed to support sub­ national governments in formulating and implementing climate adap­ tation policies, especially for the agriculture sector. This framework can be used in other countries for devising and analyzing climate adaptation policies, particularly for the subnational agriculture sector and gover­ nance initiatives. However, the framework can also be adjusted and applied in other sectors within the domain of subnational adaptation policies and action plans. Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft. Jose A. Puppim de Oliveira: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Declaration of Competing Interest The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Data Availability The relevant data details have been given in Appindex-A. Acknowledgements Jose A Puppim de Oliveira acknowledges the support of FAPESP (Grant #2017/50425-9), CAPES (Grant #88881.310380/2018-01), CNPq (Grant #303117/2022-2), and HEC (Grant #1-8/HEC/HRD/ 2017/8450) as well as FGV EAESP. Jose A. Puppim de Oliveira is also Visiting Fudan Chair Professor, Institute for Global Public Policy (IGPP), Fudan University, China.The authors contributed equally to the writing of the article. CRediT authorship contribution statement Muhammad Mumtaz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Appendix A Respondents’ Profiles. Respondent ID Respondents’ responsibilities/ roles Respondents’ Organization 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Inspector General Forests Director General Environment Charmain and member of board of governance Professor of Policy Study and Sustainable Development Head of Department Professor of water and climate change Senior Researcher for agriculture and climate change Senior Researcher for climate change and head for the water section Researcher for climate change and agriculture sector General Manager and compiling climate change data in Pakistan Director of Agronomic and an active member for climate negotiation and policies in Punjab PhD student working on climate adaptation and the agriculture sector Regional Director for agriculture extension department Deputy Director dealing with climate change in the Punjab region Farmer’s community(7 interviews) Director working on climate adaptation strategies Professor of Environmental Sciences Deputy Director and involved in framing climate policy in the KPK Professor of agriculture and climate change Manager dealing with agriculture extension in the KPK Chief Manager for planning in the agriculture sector Climate change policy researcher Director dealing with floods and rescues 24 Farmer’s community(7 interviews) Ministry of Climate Change Ministry of Climate Change Sustainable Development Policy Institute Center for Policy Study, COMSATS University, Islamabad Center for Climate Research and development Department of Meteorology, COMSATS University, Islamabad Global Change Impact Studies Center Global Change Impact Studies Center Pakistan Agriculture Research Council Pakistan Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission Ayub Agriculture Research Institute, Faisalabad University of Agriculture, Faisalabad Agriculture Extension Department in Faisalabad Environmental Protection Agency in Lahore, Punjab Farmers in Punjab Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation organization, Peshawar, Pakistan University of Peshawar Center for Climate Change, Peshawar Agriculture University Peshawar Agriculture extension department, Peshawar Establishment Division Peshawar KPK Pakistan Forest Institute, Peshawar Provincial Disaster Management Authority, KPK Farmers in the KPK Appendix B Criterion for Analysis. 134 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 Component of proposed framework Indicators for the components of the proposed framework √√√ √√ √ Locally Driven Engagement of local actors When there are evidences that all the related local actors are involved and their concerns are taken Evidences of involvement of local actors and they are partially satisfied with the actions taken Incorporation of hidden adaptation When the impact or the hidden adaptation are identified and included in action plans When the impact or the hidden adaptation are identified and willing to incorporate it in action plans Research and innovation at Local academic institutions When the climate related courses are there, climate studies are conducted and the research studies are quoted or cited in government’s documents When the policy implementation is monitored, evaluated, and used to improve/revise the initiatives A small number of research studies are conducted and partially the impact can be seen in public documents Local Institutionalization When the local institutions are involved in policy framing and implementation Institutional mechanism of coordination When the involvement of all related institutions are there in implementation phase When partial engagement of local institutions are seen. The concerns of all relevant departments are not addressed When some related institutions are there in implementation phase and some are missing Allocation of financial budget When the budget is allocated as per the required amount to address climate change When the laws are enacted and implementing actions are taken as per laws. When the proper accountability and transparency system is there. The evidences show that institutions are being accountable for their actions. When at the local, subnational, and nation level are at the same page and there is coherence for actions taken at these level When there are evidences of involvement of international organization for actions taken at subnational level. Securing of reasonable funding from international funds. Viable governments’ commitment to involve local actors. This is written in documents or seen by the government people When the local governments recognized the hidden adaptation but yet to include in their existing plans when the importance of research and innovation is recognized by the subnational government When the monitoring and evaluation for implementation of subnational policies are emphasized When the importance of local institutions are highlighted by the subnational government When the coordination among local institutions are emphasized but yet to take steps to properly involve them When there is will and plan to set climate change budget Locally Monitoring and Evaluation Institutionally Capable Legally Strong Legal backing for implementing policies Legally accountability and transparency Intergovernmental institutions relations National, Subnational, and local level institutional linkages Incorporation of International efforts References When the policy implementation is monitored and but no evidence the use for improve/revise the initiatives When the budget is allocated but it is not reasonable amount to address climate change When some laws are enacted but implementing actions are taken as per laws. When the accountability and transparency system is there but no evidences that institutions are being accountable for their actions. When at the local, subnational, and nation level are not in the same line for actions taken. When there are no evidences of involvement of international organizations for actions taken at subnational level. Limited or no fund is secured from international funds. When the legal backing is promoted but yet to enact any law. When the accountability and transparency system is recognized but yet to incorporate it in actionable form When the linkage among the local, subnational, and nation level is recognized but there is no evidence that how they are taking steps When the relations with international organizations are recognized but yet to take practical steps Birchall, S.J., Kehler, S., 2023. Denial and discretion as a governance process: How actor perceptions of risk and responsibility hinder adaptation to climate change. Environ. Sci. Policy 147, 1–10. Bodansky, D., Hoedl, S., Metcalf, G.E., Stavins, R.N., 2014. Facilitating linkage of heterogeneous regional, national, and sub-national climate policies through a future international agreement. Harv. Proj. Clim. Agreem. Borrás, S., Edquist, C., 2013. The choice of innovation policy instruments. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80 (8), 1513–1522. Bulkeley, H., Schroeder, H., Janda, K., Zhao, J., Armstrong, A., Chu, S.Y., Ghosh, S., 2009. Cities and climate change: the role of institutions, governance and urban planning. Change 28, 30. Cattivelli, V., 2021. Climate adaptation strategies and associated governance structures in mountain areas. the case of the alpine regions. Sustainability 13 (5), 2810. Chaudhry, Q., 2017. Climate change profile of Pakistan. Asian Dev. Bank, Manila, Philipp. Clar, C., Steurer, R., 2019. Climate change adaptation at different levels of government: Characteristics and conditions of policy change. In: Natural Resources Forum, Vol. 43. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK, pp. 121–131 (May). Crouch, C., Streeck, W., Whitley, R., Campbell, J.L., 2007. Institutional change and globalization. Socio-Econ. Rev. 5 (3), 527–567. Dawson, R., 2007. Re-engineering cities: a framework for adaptation to global change. Philosophical transactions of the royal society of london a: mathematical. Phys. Eng. Sci. 365 (1861), 3085–3098. Dessai, S., Hulme, M., 2004. Does climate adaptation policy need probabilities? Clim. Policy 4 (2), 107–128. Dhungana, N., Khadka, C., Bhatta, B., Regmi, S., 2017. Barriers in local climate change adaption planning in Nepal. JL Pol. ’Y. Glob. 62, 20. Evans, M., Marsh, D., Stoker, G., 2013. Understanding localism. Policy Stud. 34 (4), 401–407. Adger, W.N., Kelly, P.M., 1999. Social vulnerability to climate change and the architecture of entitlements. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 4 (3), 253–266. Agrawal, A., 2010. Local institutions and adaptation to climate change. Soc. Dimens. Clim. Chang.: Equity vulnerability a Warm. World 2, 173–178. Alford, J., Hartley, J., Yates, S., Hughes, O., 2017. Into the purple zone: deconstructing the politics/administration distinction. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 47 (7), 752–763. Ali, A., Erenstein, O., 2017. Assessing farmer use of climate change adaptation practices and impacts on food security and poverty in Pakistan. Clim. Risk Manag. 16, 183–194. Allain-Dupré, D., 2011. Multi-Lev. Gov. Public Invest.: Lessons Crisis. Anderton, K., Setzer, J., 2018. Subnational climate entrepreneurship: innovative climate action in California and São Paulo. Reg. Environ. Change 18 (5), 1273–1284. Andonova, L.B., Mitchell, R.B., 2010. The rescaling of global environmental politics. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 255–282. Aslam, A., Rana, I.A., 2022. Impact of the built environment on climate change risk perception and psychological distancing: empirical evidence from Islamabad, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Policy 127, 228–240. Averchenkova, A., Bassi, S., 2016. Beyond Target.: Assess. Political Credibil. pledges Paris Agreem. Bansard, J.S., Pattberg, P.H., Widerberg, O., 2017. Cities to the rescue? assessing the performance of transnational municipal networks in global climate governance. Int. Environ. Agreem.: Polit., Law Econ. 17 (2), 229–246. Below, T., Artner, A., Siebert, R., Sieber, S., 2010. Micro-level practices to adapt to climate change for African small-scale farmers. A Rev. Sel. Lit. 953, 1–20. Berman, R.J., Quinn, C.H., Paavola, J., 2015. Identifying drivers of household coping strategies to multiple climatic hazards in Western Uganda: implications for adapting to future climate change. Clim. Dev. 7 (1), 71–84. 135 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 Mumtaz, M., de Oliveira, J.A.P., Ali, S.H., 2019. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Agricultural Sector: The Case of Local Responses in Punjab, Pakistan. Climate Change and Agriculture. Intech Open. Nelson, R., Howden, M., Smith, M.S., 2008. Using adaptive governance to rethink the way science supports Australian drought policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 11 (7), 588–601. Neset, T.S., Wiréhn, L., Opach, T., Glaas, E., Linnér, B.O., 2019. Evaluation of indicators for agricultural vulnerability to climate change: the case of Swedish agriculture. Ecol. Indic. 105, 571–580. Newsham, A.J., Thomas, D.S.G., 2011. Knowing, farming and climate change adaptation in North-Central Namibia. Glob. Environ. Change 21 (2), 761–770. Niles, M.T., Lubell, M., Haden, V.R., 2013. Perceptions and responses to climate policy risks among California farmers. Glob. Environ. Change 23 (6), 1752–1760. Njuguna, L., Biesbroek, R., Crane, T.A., Tamás, P., Dewulf, A., 2022. Designing fit-forcontext climate change adaptation tracking: Towards a framework for analyzing the institutional structures of knowledge production and use. Clim. Risk Manag. 35, 100401. Nkiaka, E., Lovett, J.C., 2018. Mainstreaming climate adaptation into sectoral policies in Central Africa: Insights from Cameroun. Environ. Sci. Policy 89, 49–58. Oberlack, C., Eisenack, K., 2014. Alleviating barriers to urban climate change adaptation through international cooperation. Glob. Environ. Change 24, 349–362. OECD, 2012. The Interface Between Subnational and National Levels of Government. OECD. Ogalleh, S.A., Vogl, C.R., Eitzinger, J., Hauser, M., 2012. Local perceptions and responses to climate change and variability: the case of Laikipia District, Kenya. Sustainability 4 (12), 3302–3325. Osofsky, H.M., 2007. Local approaches to transnational corporate responsibility: Mapping the role of subnational climate change litigation. Pac. McGeorge Glob. Bus. Dev. LJ 20, 143. Oxfam & Consortium, I.2017, Climate Public Expenditure Review (CPER) in Punjab (2015–17). 〈http://www.indusconsortium.pk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Climat e-Public-Expenditure-2.pdf〉. Pervin, M., Sultana, S., Phirum, A., Camara, I.F., Nzau, V.M., Phonnasane, V., Anderson, S. , 2013. A framework for mainstreaming climate resilience into development planning. International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK. Picavet, M.E.B., de Macedo, L.S., Bellezoni, R.A., Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., 2023. How can transnational municipal networks foster local collaborative governance regimes for environmental management? Environ. Manag. 71, 505–522. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00267-022-01685-w. Pinto, R.F., Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., 2008. Implementation challenges in protecting the global environmental commons: The case of climate change policies in Brazil. Public Adm. Dev.: Int. J. Manag. Res. Pract. 28 (5), 340–350. Pradhan, N.S., Su, Y., Fu, Y., Zhang, L., Yang, Y., 2017. Analyzing the effectiveness of policy implementation at the local level: a case study of management of the 2009–2010 drought in Yunnan Province, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 8 (1), 64–77. Prasad, R.S., Sud, R., 2019. Implementing climate change adaptation: lessons from India’s national adaptation fund on climate change (NAFCC). Clim. Policy 19 (3), 354–366. Preston, B.L., 2013. Local path dependence of US socio-economic exposure to climate extremes and the vulnerability commitment. Glob. Environ. Change 23 (4), 719–732. Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., 2009. The implementation of climate change related policies at the subnational level: an analysis of three countries. Habitat Int. 33 (3), 253–259. Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., 2019. Intergovernmental relations for environmental governance: cases of solid waste management and climate change in two Malaysian States. J. Environ. Manag. 233, 481–488. Puppim de Oliveira, J.A.P., 2005. Enforcing protected area guidelines in Brazil: what explains participation in the implementation process? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 24 (4), 420–436. Putnam, R.D., Leonardi, R., Nanetti, R.Y., 1994. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princet. Univ. Press. Qi, Y., Wu, T., 2013. The politics of climate change in China. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 4 (4), 301–313. Ragin, C.C., Becker, H.S., 1992. What is a case?: Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry. Cambridge University Press. Rehman, A., Jingdong, L., Shahzad, B., Chandio, A.A., Hussain, I., Nabi, G., Iqbal, M.S., 2015. Economic perspectives of major field crops of Pakistan: An empirical study. Pac. Sci. Rev. B: Humanit. Soc. Sci. 1 (3), 145–158. Ren, B., Zhang, J., Li, X., Fan, X., Dong, S., Liu, P., Zhao, B., 2014. Effects of waterlogging on the yield and growth of summer maize under field conditions. Can. J. Plant Sci. 94 (1), 23–31. Rojas-Downing, M.M., Nejadhashemi, A.P., Harrigan, T., Woznicki, S.A., 2017. Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Clim. Risk Manag. 16, 145–163. Roppongi, H., Suwa, A., Puppim De Oliveira, J.A., 2017. Innovating in sub-national climate policy: the mandatory emissions reduction scheme in Tokyo. Clim. Policy 17 (4), 516–532. Savitch, H.V., Savitch, H.V., Kantor, P., Vicari, S.H., 2002. Cities in the international marketplace: The political economy of urban development in North America and Western Europe. Princeton University Press. Setzer, J., 2013. Environmental paradiplomacy: the engagement of the Brazilian state of São Paulo in international environmental relations. Lond. Sch. Econ. Political Sci. (LSE). Faisal, M., Chunping, X., Akhtar, S., Raza, M.H., Khan, M.T.I., Ajmal, M.A., 2020. Modeling smallholder livestock herders’ intentions to adopt climate smart practices: an extended theory of planned behavior. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (31), 39105–39122. FAO, 2013. Climate-smart agriculture sourcebook executive summary. Indones. Farmers gear face Chall. Clim. Change. 〈http://www.fao.org/indonesia/news/detailevents /ru/c/1110775/〉. Fünfgeld, H., 2015. Facilitating local climate change adaptation through transnational municipal networks. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 12, 67–73. Furumo, P.R., Lambin, E.F., 2020. Scaling up zero-deforestation initiatives through public-private partnerships: A look inside post-conflict Colombia. Glob. Environ. Change 62, 102055. Hallegatte, S., 2009. Strategies to adapt to an uncertain climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 19, 240–247. Hanif, U., Syed, S.H., Ahmad, R., Malik, K.A., Nasir, M., 2010. Economic impact of climate change on the agricultural sector of Punjab [with comments]. Pak. Dev. Rev. 771–798. Hardee, K., Mutunga, C., 2010. Strengthening the link between climate change adaptation and national development plans: lessons from the case of population in National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs). Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 15 (2), 113–126. Herath, T., Rao, H.R., 2009. Encouraging information security behaviors in organizations: role of penalties, pressures and perceived effectiveness. Decis. Support Syst. 47 (2), 154–165. Huntjens, P., Lebel, L., Pahl-Wostl, C., Camkin, J., Schulze, R., Kranz, N., 2012. Institutional design propositions for the governance of adaptation to climate change in the water sector. Glob. Environ. Change 22 (1), 67–81. Jörgensen, K. , 2011. Climate initiatives at the subnational level of the Indian states and their interplay with federal policies. In 2011 ISA Annual Convention (pp. 16–19). Kassie, B.T., Asseng, S., Rotter, R.P., Hengsdijk, H., Ruane, A.C., Van Ittersum, M.K., 2015. Exploring climate change impacts and adaptation options for maize production in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia using different climate change scenarios and crop models. Clim. Change 129 (1–2), 145–158. Kehler, S., Birchall, S.J., 2023. Climate change adaptation: How short-term political priorities trample public well-being. Environ. Sci. Policy 146, 144–150. Khan, M.A., 2012. Agricultural development in Khyber Pakhtun Khwa: prospects, challenges and policy options. Pak. A J. Pak. Stud. 4 (1), 49–68. Knox, J., Hess, T., Daccache, A., Wheeler, T., 2012. Climate change impacts on crop productivity in Africa and South Asia. Environ. Res. Lett. 7 (3), 34032. Lachapelle, E., Paterson, M., 2013. Drivers of national climate policy. Clim. Policy 13 (5), 547–571. Lipper, L., Thornton, P., Campbell, B.M., Baedeker, T., Braimoh, A., Bwalya, M., Henry, K., 2014. Climate-smart agriculture for food security. Nat. Clim. Change 4 (12), 1068. Macedo, L., Jacobi, P., Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., 2023. Paradiplomacy of cities in the global south and multilevel climate governance: evidence from Brazil (in press). Glob. Public Policy Gov. Madzwamuse, M., 2010. Climate governance in Africa: adaptation strategy and institutions. A Synth. Rep. Submitt. Heinrich Böll Stift. Mahmood, Z., Iftikhar, S., Saboor, A., Khan, A.U., Khan, M., 2016. Agriculture land resources and food security nexus in Punjab, Pakistan: an empirical ascertainment. Food Agric. Immunol. 27 (1), 52–71. Mearns, L.O., Gutowski, W., Jones, R., Leung, R., McGinnis, S., Nunes, A., Qian, Y., 2009. A regional climate change assessment program for North America. Eos, Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 90 (36), 311. Mertz, O., Mbow, C., Reenberg, A., Diouf, A., 2009. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and agricultural adaptation strategies in rural Sahel. Environ. Manag. 43 (5), 804–816. Michaelowa, K., Michaelowa, A., 2017. Transnational climate governance initiatives: designed for effective climate change mitigation? Int. Interact. 43 (1), 129–155. Milhorance, C., Le Coq, J.F., Sabourin, E., Andrieu, N., Mesquita, P., Cavalcante, L., Nogueira, D., 2022a. A policy mix approach for assessing rural household resilience to climate shocks: Insights from Northeast Brazil. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 20 (4), 675–691. Milhorance, C., Sabourin, E., Chechi, L., Mendes, P., 2022b. The politics of climate change adaptation in Brazil: framings and policy outcomes for the rural sector. Environ. Polit. 31 (2), 183–204. Mubaya, C.P., Njuki, J., Mutsvangwa, E.P., Mugabe, F.T., Nanja, D., 2012. Climate variability and change or multiple stressors? Farmer perceptions regarding threats to livelihoods in Zimbabwe and Zambia. J. Environ. Manag. 102, 9–17. Muench, S., Bavorova, M., Pradhan, P., 2021. Climate change adaptation by smallholder tea farmers: a case study of Nepal. Environ. Sci. Policy 116, 136–146. Mukheibir, P., Ziervogel, G., 2007. Developing a Municipal Adaptation Plan (MAP) for climate change: the city of Cape Town. Environ. Urban. 19 (1), 143–158. Mumtaz, M., 2021. Role of civil society organizations for promoting green and blue infrastructure to adapting climate change: Evidence from Islamabad city, Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 309, 127296. Mumtaz, M., 2023. Intergovernmental relations in climate change governance: A Pakistani case. Glob. Public Policy Gov. 3, 116–136. Mumtaz, M., Ali, S.H., 2019. Adaptive governance and sub-national climate change policy: a comparative analysis of Khyber Pukhtunkhawa and Punjab provinces in Pakistan. Complex., Gov. Netw. 5 (1), 81–100. Mumtaz, M., Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., 2019. Impacts of water crises on agriculture sector and governance challenges in Pakistan. Cuvillier Verlag,, Germany, pp. 270–281. 136 M. Mumtaz and J.A. Puppim de Oliveira Environmental Science and Policy 147 (2023) 126–137 Tonmoy, F.N., Cooke, S.M., Armstrong, F., Rissik, D., 2020. From science to policy: development of a climate change adaptation plan for the health and wellbeing sector in Queensland, Australia. Environ. Sci. Policy 108, 1–13. Urwin, K., Jordan, A., 2008. Does public policy support or undermine climate change adaptation? exploring policy interplay across different scales of governance. Glob. Environ. Change 18 (1), 180–191. Vermeulen, S.J., Campbell, B.M., Ingram, J.S.I., 2012. Climate change and food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 37, 195–222. Vij, S., Moors, E., Ahmad, B., Uzzaman, A., Bhadwal, S., Biesbroek, R., Gioli, G., Groot, A., Mallick, D., Regmi, B., 2017. Climate adaptation approaches and key policy characteristics: cases from south Asia. Environ. Sci. Policy 78, 58–65. Wamsler, C., Schäpke, N., Fraude, C., Stasiak, D., Bruhn, T., Lawrence, M., Schroeder, H., Mundaca, L., 2020. Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environ. Sci. Policy 112, 227–235. Weber, E.P., Khademian, A.M., 2008. Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public Adm. Rev. 68 (2), 334–349. Weiss, T.G., Seyle, D.C., Coolidge, K., 2013. The Rise of Non-State Actors in Global Governance: Opportunities and Limitations. Discussion Paper. One Earth Future Foundation, 2013,, Broomfield. Westermann, O., Thornton, P.K., Förch, W., 2015. Reach. more Farmer.: Innov. Approaches scaling Clim. -smart Agric. Wise, R.M., Fazey, I., Smith, M.S., Park, S.E., Eakin, H.C., Van Garderen, E.A., Campbell, B., 2014. Reconceptualising adaptation to climate change as part of pathways of change and response. Glob. Environ. Change 28, 325–336. Yamin, F., Rahman, A., Huq, S., 2005. Vulnerability, adaptation and climate disasters: a conceptual overview. IDS Bull. 36 (4), 1–14. Zhao, D., Li, Y.-R., 2015. Climate change and sugarcane production: potential impact and mitigation strategies. Int. J. Agron. 2015. Ziervogel, G., Bharwani, S., Downing, T.E., 2006. Adapting to climate variability: pumpkins, people and policy. In: Natural resources forum, Vol. 30. Wiley Online Library,, pp. 294–305. Setzer, J., Vanhala, L.C., 2019. Climate change litigation: a review of research on courts and litigants in climate governance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 10 (3), e580. Shukla, R., Gleixner, S., Yalew, A.W., Schauberger, B., Sietz, D., Gornott, C., 2021. Dynamic vulnerability of smallholder agricultural systems in the face of climate change for Ethiopia. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 (4), 044007. Singh, R., Singh, G.S., 2017. Traditional agriculture: a climate-smart approach for sustainable food production. Energy, Ecol. Environ. 2 (5), 296–316. Smucker, T.A., Nijbroek, R., 2020. Foundations for convergence: Sub-national collaboration at the nexus of climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and land restoration under multi-level governance in Kenya. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 51, 101834. Soubry, B., 2017. How can governments support adaptation to climate change by smallscale farmers? A case study from the Canadian Maritime provinces. A Case Study Can. Marit. Prov. Sumra, K., Mumtaz, M., Khan, K., 2020. National Water Policy of Pakistan: A Critical Analysis. J. Manag. Sci. 14. Tanner, T., Mitchell, T., Polack, E., Guenther, B., 2009. Urban governance for adaptation: assessing climate change resilience in ten Asian cities. IDS Work. Papers, 2009 (315), 1–47. Termeer, C., Dewulf, A., Van Rijswick, H., Van Buuren, A., Huitema, D., Meijerink, S., Wiering, M., 2011. The regional governance of climate adaptation: a framework for developing legitimate, effective, and resilient governance arrangements. Clim. Law 2 (2), 159–179. Thrän, D., Schaubach, K., Majer, S., Horschig, T., 2020. Governance of sustainability in the German biogas sector—adaptive management of the Renewable Energy Act between agriculture and the energy sector. Energy, Sustain. Soc. 10 (1), 1–18. Tiwari, K.R., Rayamajhi, S., Pokharel, R.K., Balla, M.K., 2014. Does Nepal’s climate change adaption policy and practices address poor and vulnerable communities. JL Pol. ’Y. Glob. 23, 28. Tompkins, E.L., Adger, W.N., 2005. Defining response capacity to enhance climate change policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 8 (6), 562–571. 137