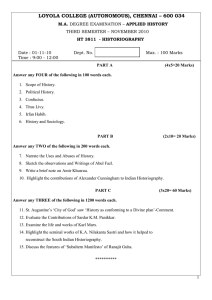

The Rise and Growth of Islamic Historiography Penned by: Dr. S.S. Waheedulla Hussaini Quadri Multani In this article we are going to discuss the rise and growth of Islamic Historiography. Before discussing the topic at length, it is incumbent upon us to know the meaning of historiography. The word historiography is extracted from the Greek historiographia: historia, history and graphia, graphy, mean craft of writing history. In Arabic it is known as ‘Ilm al-tārīkh. Academically historiography grows up as a part of knowledge in ancient Greece by Herodotus. In its most general sense, the term refers to the study of historians' methods and practices. Historiography itself is a discipline dealing with the methods of writing history and the techniques of the historical research and documentation. Historiography is therefore an important component of historical education, because it is a guide for evaluating the interpretation of historical events, to consider different ways of viewing the same evidence and many different answers to vexed historical questions. According to the WordNet Search engine at Princeton University, historiography is defined as “a body of historical literature” or “the writing of history.”1 According to the Concordia University of Wisconsin, historiography is “the written record of what is known of human lives and societies in the past and how historians have attempted to understand them.”2 In combining these two definitions, the term ‘historiography’ ultimately means the writing of history and how historians come to understand written records. 1 2 "WordNet Search." Princeton University. <http://wordnet.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=historiography>. "Historiography." Concordia University (2008) 15 Jun 2008. <http://www.cuw.edu/Academics/programs/history/historiography.html>. 1 Due to the historian’s own worldview, ideological bent, explanation based on their assigned readings, historian often disagree over why events happen and the ways in which history happens, according to various schools of thought, this leads to multiple explanations, which at times, are diametrically opposed to each other. As students progress into upper-level courses in the Department of History, they must move from the mastery of facts and analysis of primary sources encouraged by lower-level courses to a richer and deeper understanding of how history is written and the fact that events and ideas are open to interpretation. Therefore, historiography can be described as the study of how historians interpret the past and how history itself is written or handed down throughout the ages, with a particular focus on its different methods, perspectives and interpretations instead of just looking at chronology and details. That is why historiography is referred as meta-level analysis of descriptions of the past, the study of historical writing and principles of evaluating historical sources. Historiography includes the various factors like credibility of the sources used, the motives of the author composing the history, cultural, social and political lenses through which we are viewing the historical facts and events. In essence, we are trying to understand not just what a book or article is saying, but from what perspective was it written. In other words the term historiography basically refers to the writing of history based on the critical examination of sources, the selection of particular details from the authentic materials in those sources, and the synthesis of those details into a narrative that stands the test of critical examination. This means that the historiographer does not merely accept the content of a source at face value, but traces the source looking for various motifs in its formation. In a nutshell, we may conclude that the historiography is the narrative presentation of history based on critical evaluation, selection of material from primary and secondary sources and subject to scholarly criteria. It has been rightly said that the 2 historiography is based on the assumption that history is not a concrete set of facts but an ongoing discussion about the past. Historiography is important for all historians regardless of the audience they are addressing because it offers a level of transparency that allows others to see where you are getting your information from. To begin to understand historiography in the strict true sense it is important to recognize first, that ‘the past’ and ‘history’ are not the same thing. The past refers the people, societies and events of times gone by, whereas history is the process by which we try to understand and explain the past. In other words history is the story of our past, and the study of it plays a vital role in our knowledge. Thus History can be defined as "A continuous, chronological record of important or public events and the study of past events".3 In ancient times, even before the appearance of writing, historical concepts and some elements of historical knowledge existed among all peoples in orally transmitted tales and legends and in the genealogies of ancestors. Arab also relying instead on the more plaint medium of orality in pre-Islamic era, as a result Arabs also produced very little written material. Orality’s highest register was apparently occupied by poetry, particularly the ode. Before Islam, Makkah was a center of Arabic poetry. Poetry offered a currency in which a wide variety of cultural transactions could be made, and it is in poetry that we can also recover some sense of the pre-Islamic Arabs’ conceptions of time and fate. Annual festivals were held every year that brought together the best poets from all over the Arabian Peninsula. Exuberant attendees would memorize the exact words that their favorite poets recited and quote them years and decades later. The Arabs preserved their histories, genealogies detailed description of the heroic deeds of the tribes and clans in a form of poems and they use to memorize them. The poetry is to be known as the archive of the Arabs. The Arabs encouraged children to memorize them, that is why formal writing system and verbal transmission from generation to generation by word of mouth rather than ink and paper. 3 Judy Pearsall and Bill Tumball, The Oxford English Reference Dictionary, p. 669. 3 The advent of Islam, clear-cut injunctions of the Holy Qur’ān and numerous prophet traditions4 on the importance of knowledge and pen paved the way for the growth of historiography in Arabia, oral tradition, storytelling, verbal transmission evolved into writing and passing on and recording of knowledge become a timehonored tradition. Allāh Himself makes an oath with pen. Qur’ān says, 5 ُ ن ۚ َو ْالقَلَ ِم َو َما يَ ْس َط ُرون “Nūn6, By the pen and by what they write”7 According to some scholars8, Nūn9 in the verse-1 refers to the ink container10 because the shape of ‘Arabic alphabet Nūn is just like the shape of the inkwell. Al-Qalam refers to pen. According to Scholars there are three main opinions about the pen referred here. 1) The pen which is the first creation of Allāh.11 2) The pen used by the angels to write our deeds.12 3) As the symbol of knowledge The oath is quite astonishing, since the object of the oath is seemingly an insignificant point, a piece of reed or something resembling the same and a little According to a ḥadīth the ink of scholars is weighed on the Day of Judgement with the blood of martyrs and the ink of scholars outweighs the blood of martyrs. (Ibn-i Jawzī fi ‘Ilal). The reason being that martyr is engaged in defense work while an ‘ālim (scholar) builds individuals and nations along positive lines. In this way he bestows a real life to the world. Here Scholars’ ink, refers to writing, particularly history. 5 Transliteration: Nūn wal qalami wamā yasṭurūn. 6 Allāh swore by the pen because it is with this pen that the Wise Remembrance, i.e., the Guarded Tablet, was written. 7 The Qur’ān, chapter no. 68 verse nos. 1-2. 8 For detail see ‘Abdullāh bin ‘Abbās, Tanwīr al-Miqbās min Tafsīr Ibn ‘Abbās, English tr by Mokrane Guezzou, p. 786. 9 Nūn is one of the ḥurūf-i muqaṭt‘āt (the disjointed letters). There are twenty nine Sūrahs in the Qur’ān that begin with such words. At some places, there is only letter such as Nūn, Qāf and Ṣwād. At other places two letters appear for example, Yā-Sīn, Ṭā-Ha and Ḥā-Mīm. Some begin with three like Alif Lām Mīm, some start with four like Alif Lām Mīm Ṣwād and even five letters like Kāf Hā Yā ‘Ayn Ṣwād but five is the largest amount. 10 It is also said that Nūn is one of the names of the Lord; it stands for the letter Nūn in Allāh’s name al-Raḥmān (the Beneficent). Tanwīr al-Miqbās min Tafsīr Ibn ‘Abbās, English tr by Mokrane Guezzou, p. 786. 11 This is the pen through which destinies of every creation has been written down till the end of times. The Prophet said, "Indeed, the first created by Allāh is the Pen, and He said to him, “Write!”. It asked “What should I write?” and Allāh replied, “Write a decree of all things until the Day of Judgement comes." (Abū Dāwūd) 12 “Not a word does he utter but there is a sentinel by him, ready (to note it),” The Qur’ān, 50:18. 4 4 black material. Nonetheless, it is the fountainhead of all human civilizations, advancements, and development of sciences, awakening of thought, formation of religions and schools of thought, and the springhead of human guidance and awareness such that human life thereby falls into pre-historic and historic eras. Human history begins by the discovery of writing through which man was able to record the story of his life and left behind. Therefore, Abul Fidā Ismā‘īl bin ‘Umar bin Kathīr (701-774 /1300-1373)13 writes that Allāh is alerting His creatures to what He has favored them with by teaching them the skill of writing, through which knowledge is attained. The Qur’ān further says. 14 علَّ َم ِب ۡالقَلَ ِم َ ک ۡاۡلَ ۡک َر ُم الَّ ِذ ۡی َ ُّا ِۡق َر ۡا َو َرب “Read: And thy Lord is the Most Bounteous Who has taught man by the pen”15 The spirit of the Qur’ān conducive to historical research and development of historiography. Apart from several important functions and great benefits, the vital role of a pen in human life is that it is alone is the repository of human civilization and culture. It exists in order to preserve the past knowledge. This is the secret of the evolution of human civilization, and this is the reason why man is superior to other animals. A crow still follows the procedure to make the same nest as he did million years ago. It has neither made any changes nor progress. But on the other hand man has reached the moon. All this progress has been possible because the experience and knowledge of the past was preserved and man continued to add his own experience to the vast store of knowledge from which he benefits constantly. And all this is owing to the pen. 13 All dates are given according to both the Islamic and Gregorian Calendars. Transliteration: Iqra’ wa rabbukal akramullazī ‘allama bilqalam. 15 The Qur’ān, 96:4-5. 14 5 Historiography originated with the aim of elaborating the Qur’ānic view of religious history, according to which Adam was the first bearer of the divine message and Muḥammad the last. The abundance of other historical data in the holy Qur’ān provided the followers of Islam with an incentive to study history. As a result of the quick and everlasting impact of the above cited Qur’ānic verses on the Muslims of the Arab and their firm response to the teachings of the Qur’ān and the Ḥadīth, they took conscious effort to preserve and transmit the holy Qur’ān. According to the tradition of Ṭabarī, there are forty two persons who were engaged in wrote down the revelations during the lifetime of the noble Muḥammad (PBUH) itself.16 Muslim historians considered historiography to be the third source of knowledge after the research of Qur’ān and Sunnah. The holy Qur’ān and the Sunnah of the Prophet forms the major sources of Islamic Jurisprudence and so, they both constitute the source of historical writing. From historical point of view the Qur’ān is the first, the most authentic and the oldest available source of history of Islam. Due to preservation and recitation of the Qur’ān from the very beginning by Prophet and his followers five times a day in obligatory prayer, we can says that what is referred to in the Qur’ān is also, historically, the most dependable version of the event. Historian describes the genesis, history of prophethood, social conditions and evils prevail in ‘Arabia before advent of Islam, references to all these events are to be found in the Qur’ān. Tafsīr of the holy Qur’ān was another important aspect of the intellectual activities that directly influenced the historical literature as well as the historiographical attitudes of the early Muslims. Jāmi‘ al-Bayān fī Tafsīr alQur’ān, considered one of the standard books on the subject of exegesis. It is a collection of traditional exegesis giving historical, lexicographical, grammatical 16 A.M. Khan, Historical Value of The Qur’ān and The Ḥadīth, p. 31. Some of the scriber of the Holy Qur’ān are listed as follows: Abū Bakr, Uthmān and ‘Alī ‘Āmir bin Fuhaira, Zubair bin al-‘wām, Ubayy bin Ka‘b, Ḥanzalah bin al-Rabī‘, Zaid bin Thābit, Ubayy bin Fāṭimah, Mughīrah bin Mushīr, al-‘Ala bin al-Ḥadramī, Khālid bin alWalīd, ‘Abdullāh bin Arqam, Shurhabil bin Ḥasana, ‘Abdullāh bin Rawāḥah, Mu‘āwiyah, Yazīd bin Abī Sufyān, Thābit bin Qais, Khālid bin Sa‘īd and Ābān bin Sa‘īd. 6 and legal information. Tafsīr and historiography shared an interest in collecting the complete information on the individual prophets. Defining Tafsīr as a genealogical literature is not only a way of describing the internal mechanism of this genre, but it also helps us study its historical development by allowing us to determine which works were essential in the history of the genre. Tafsīr acquired the stability of a defined genre via the network of cited authorities and the connections between the different authorities inside a particular corpus of citations. The historiography of Tafsīr in the Arab world is very rich. Tafsīr historiography in the Arab world was conscious of the latest developments in Orientalism. Modern Arabic historiography of Tafsīr is thus a complicated affair and reflects the deep rifts in the Islamic religious tradition on the eve of modernity. Prophet of Islam discouraged his followers, in the initial stages of his mission, to write about him in order to prevent any confusion between his sayings and the Qur’ān.17 However the reports about the alteration of this attitude in a later stadium encouraged the biographers to write sīrah or biographical collections at the end of the first and beginning of the second Islamic century. Prophet’s approval to write the Qur’ān, the Ḥadīth and the biography of the Prophet opened the way for the production of more than 590 historical books in one millennium, including the campaigns of the noble prophet (maghāzī) and the conquests (futūḥ). One of the peculiarities of Muslim historiography was the liking for encyclopedic dictionaries of famous men. The earliest of these were devoted to the Companions of Muḥammad and to the early transmitters of the Muslim traditions. For a thousand years extremely diverse types of biographical collections have continued to appear in the Muslim world. Muslim historians compiled more historical works than were collectively compiled in any other language. A survey of the historical works conducted by F. Wustendfeld showed the number of works written during 17 Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim´s ḥadīth collection narrated from Abī Sa‘īd al-Khudrī. 7 the first millennium as 590 books.18 While Ḥājī Khalīfah (1018-1068/1609-1657), the author of ( کشف الظنون عن اسامی الکتب والفنونKashfuz zunūn ‘an asāmī al-kutūb wal funūn) gives a list of 1,300 history books written in ‘Arabic during the first few centuries of Islam. Muslim historiography had maintained close relationship with the other religious sciences in Islam, particularly Ḥadīth. Because narratives regarding Muḥammad and his companions came from various sources, it was necessary to verify which sources were more reliable. In order to evaluate these sources, various methodologies were developed, such as the science of biography, science of ḥadīth and isnād (chain of transmission). These methodologies were later applied to other historical figures in the Muslim world. Since validating the sayings of Muḥammad is a major study isnād, accurate biography has always been of great interest to Muslim biographers, who accordingly attempted to sort out facts from accusations, bias from evidence, etc. From its earliest origins, a zealous effort to record only true statements about or by the Prophet from authoritative testimony, beginning with eyewitnesses, led to careful attention to the chain of transmission isnād whereby one successive authority passed information, often orally, down to the next. This tendency developed a scientific and critical attitudes essential in the development of historiography and historical outlook. Ḥadīth is a record of Muḥammad's words and deeds. Ḥadīth literature is an important source of the history of Islam, its advent, expansion and fundamental teachings, as well as of the life and Traditions of the Prophet of Islam, which the Companions of the Prophet preserved from the very beginning, and which, during the subsequent years attained the position of a permanent branch of knowledge. Muslims engineered an interplay between orality and literacy, between the spoken and the written word, and this interplay lies at the heart of the science of ḥadīth. This being the queen of 18 D.S. Margoliouth, Lectures on Arabic Historians, Calcutta, 1930, p. 1. 8 Islamic sciences, it also underpins other branches of knowledge. This is particularly the case for history, since many historians were first and foremost jurists, and it was from ḥadīth transmission, rather than history writing, that they would have derived their academic skills and social prestige.19 Historiography discusses writing about the past that might be described by the Arabic word tārīkh, commonly used for history or chronology, is derived from the root ‘arkh’ which means recording the time of an event; and tārīkh is actually the ‘time’ when a particular event took place. The word tarkih has a two-fold meaning. It usually means the past, be it prehistoric, ancient, medieval, modern or even contemporary, such as is recorded in a diary. But it can also describe our thinking, teaching and writing about the past that is, a discipline or branch of learning.20 Thus, tārīkh is the science of committing anecdotes and their causes to writing with reference to the time of their occurrence. In pre-Islamic times, Arabs had no permanent calendar. They used to remember or record historical material according to important incidents of their age. For example, the tribes settled in Hijaz and nearby areas, remembered the date of an event from their famous battle-days (ayyām) like the battle of Bāsūs or Fijār etc., while the Yemenite tribes counted it by the destruction of Ma‘rib Dam, and people of Ṣan‘a by the invasion of their land by the Abyssinian colonialists. But the use of permanent calendar was introduced during the rule of the second caliph ‘Umar (d. 23/643), when he appreciated a letter properly dated by his governor in Yemen Ya‘lā bin Umayyah, who had apparently followed the practice of the Yemenites. ‘Umar wanted to introduce a permanent Islamic calendar and after much deliberation adopted the Immigration (hijrah) of the noble prophet to Madīnah, as a suitable starting point of such a calendar. So he advised the Muslims 19 20 Chase F. Robinson, Islamic Historiography, p. 174. Chase F. Robinson, Islamic Historiography, preface, p. xvi. 9 in general, and the state officials in particular, to use the hijrah era for recording the date and time. In this manner Islamic historiography, a highly elaborate and systematic development of historical writing and thought about the past, begins in the seventh century, its first subject being the life and deeds or military expeditions or campaigns (maghāzī) of Muḥammad himself21, whose hijrah to Madīnah in 622 C.E. provided a firm date on which to anchor an Islamic chronology. Muslim contribution to the development of the science and knowledge, especially in the field of historiography under the Umayyad (42-132/662-750) and ‘Abbāsids (132656/750-1258) was remarkable. As early as the eighth and ninth centuries, which marked a formative period in the development of Islamic historiography, evidence ‘for an exchange of historiograhpic ideas amongst Muslims, Christans and Jews’ was already discernible.22 Sīrah (biography), maghāzī (expedition), ansāb (genealogies), ṭabaqāt (classical sketches), akhbār (information) and tārīkh (annals) were the main sources of Islamic historiography. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians have studied that topic using particular sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches. Scholars discuss historiography topically – such as the historiography of the British Empire, the historiography of China or the Islamic historiography. The study of Islamic historiography gives us an opportunity to have an indepth understanding of what history stand for in the classical, medieval and contemporary periods. Islamic historiography will be an indispensable source for the historiographical traditions of Islam. Islamic historiography means written material concerning the events from the early period of Islam, i.e., 17th century Muḥammad participated in twenty seven ghazawāt. The first ghazwā he participated in was the Invasion of Waddan in August 623. For detail see Sa‘d, Ibn, Kitāb al-ṭabaqāt al-kabīr,,vol. ii, p. 4; Ṭabarī, al, The History of al-Ṭabarī, p. 12. 22 Chase Robinson, Islamic Historiography, p. 48. Robinson cites the example that Orosius’ Historiae adversus paganos was translated into Arabic in Spain in the tenth century. But Franz Rosenthal, in A History of Muslim Historiography, pp. 80-81, does not think that his particular translation had any sort of influence on Muslim historiography. 21 10 from Muḥammad’s first revelation in AD 610. Islamic historiography is the product of a long development. Firstly, during its origin phase, i.e., the eight and early ninth centuries, the main characteristic of Islamic historiography is the explosive growth of historical narration, the literature of this era is termed as akhbār (pl. of khabar,23) which is an account of the past composed for historical interest rather than to shed light on Islamic law and often devoted to the relation of a single event. This phase was followed by a period of authoritative collecting and pruning, which produced the great bulk of the surviving texts. Secondly, the authority of original writers that is, recognizable ‘authors’ had emerged in Islamic historiography, as it had in the law and belles letters. It was a period of excessive academic achievement in the history of Islamic historiography. During this period historical study reached a stage which led to the appearance of the great historians like al-Madā’inī (d. 228/843), and al-Balādhurī (d. 280/893).24 Abul Ḥasan ‘Alī bin Muḥammad bin ‘Abdullāh bin Abī Sayf (134-228/752843), better known as al-Madā’inī from al-Madā’in, was an early Arab scholar, prolific writer and highly productive scholar with many-sided interests, great and extremely reliable specialist in the akhbār.25 He wrote over 200 works, (only two of which are extant today26 and even these only in later recessions made by is students.) including such diverse fields like zoology, geography, Arabic literature and poetry, but is best known as a historian. He was an important compiler, 23 It refers to a piece of information, report about historical events and normally consists of (1) a transmission chain of authorities (isnād) from the witness of the event to the compiling historian, and (2) the actual text (matn) of historical information. A general term for a single unit of narrative, whether historical or literary. A khabar can sometimes, albeit rarely, mean a ḥadīth, tradition of the Prophet. 24 For detail see Chase F. Robinson, Islamic Historiography, p. 39. 25 The Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. v, p. 947. 26 Two adab works of his have survived to us; the Kitāb al-Ta‘āzī, “The Book of Condolences” (extant in part), and another work with the title Risālat al-Mutazawwijāt min Quraysh, “Epistle on Qurashi Wives”, which has been edited with the title Kitāb al-Murdifāt min Quraysh, “The Qurashi Women Who [Married One Husband] After another. For further detail see Nawādir al-Makhṭuṭāt, edt. by Abd al-Salam Harun, vol. I, pp. 63-87. The main reason for lost of his works was, al-Madā’inī too, disseminated his works principally through lectures and study circles. His works, it seems, did not circulate widely in manuscript form; they were not books proper. Rather, they circulated as notebooks written down by his students. 11 evaluator, and organizer of historical and literary narratives. Most of his works survive only as quoted in the works of later authors.27 He was active under the ‘Abbāsids in Iraq in the first half of the 9th century. He wrote a number of books like Kitāb al-dawlah or Book of Nations,28 Kitāb al-awā’il or Book of Firsts, Kitāb al-murdifāt min Quraysh or The Qurashi Women Who [Married One Husband] After Another”, Kitāb al-ta‘āzī wal marāthī, or “The Book of condolences and Elegiac Orations”, Kitāb al-asāwira or Book of Horsemanship and Kitāb shihnāt al-barīd, a work on the constitution of the postal service which evidently had direct bearing on the field of administrative geography and history. 29 An important part of his works deals with historical subjects, reaching from the origins of Islam until his own days. Al-Madā’inī is quoted some 40 times in the volumes I/1 and I/2 of the Ansāb al-ashrāf written by al-Balādhurī. Al-Balādhurī’s direct and aural student relationship with al-Mada’ini is corroborated by the fact that in the rare occasions where he uses the isnād with exact technical terms, he says to have transmitted from al- Madā’inī by qira.30 Ahmad bin Yaḥyā al- Balādhurī (d. 279/893) was a 9th century Persian historian, traditionist and a boon companion of the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861), who is also considered one of Islams pre eminent historians. He was one of the chief authorities for the period during which the Arab state was in process of formation. He was also one of the eminent Middle Eastern historians of his age who wrote a book on the early conquests called ( فتوح البلدانFutūḥ al-buldān) or ‘the conquest of the lands’) is a comprehensive history of the Islamic conquests of the seventh century arranged by areas conquered and based on documents. It is an extensive biography which contains genealogical information and presents the episodic and personal character of early Islamic historiography from the Prophet and Ṭabarī, The History of al-Ṭabarī, tr. into English by Franz Rosenthal, vol. xxi, p. 45. It is book all about the events of the revolution and beginning of the ‘Abbāsid rule. It is an important early source on the matter. 29 Ibn Nadīm, Fihrist/ Persian, p. 171; Baghdadi, Tārīkh, vol. v, pp. 198-199; al-Safadi, Wāfī, vol. vi, pp. 184-185 & 444. 30 Fihrist, vol. I, p. 113, n. 57. 27 28 12 his companions to the Umayyad and ‘Abbāsid times in the episodic format and conversational framework.31 This work not only covers the conquests of lands from Arabia west to Egypt, North Africa, and Spain and east to Iraq, Iran and Sind but also covers the formation of the Arabic State, from Madīnah to Maghrib, to Andalusia, Persia, Sicily, Rhodes and Crete by the Early Arabs. It is also an important source of information on local administration and chief Muslim families. Phillip K. Hitti as regard the book opines that “The book shares with other books of Arabic history the advantage of tracing the report back to the source. Being a synopsis of a larger work, its style is characterized by condensation whereby it gains in conciseness but loses in artistic effect and clearness. Certain passages are mutilated and ambiguous. It is free from exaggeration and the flaws of imagination. Throughout the work the sincere attempt of the author to get to the fact as it happened and to record it as it reached him is felt. The chapters on colonization soldier’s pay, land tax, coinage and the like make it especially valuable.”32 He also wrote an extant work on genealogy, called ( انساب اۡلشرافAnsāb alashrāf) or genealogies of the nobles, which is a digest of a larger one, included extensive biographical information, emphasizing the importance of family tradition and ancestry as source of loyalty and examples for descendants. ‘Abbāsid reign is considered as the golden age of Islam. ‘Abbāsid caliphate covered an extensive realm that stretched across the African and Asian continents, from the western reaches of Carthage on the Mediterranean to the Indus River Valley in the east, spanning prime regions over which the Greeks, Romans, 31 For detail about the structure of Futūḥ al-buldān, see Francis C. Murgotten, Al-Balādhurī, futūḥ al-buldān, vol. ii, pp. 31-34. 32 Futūḥ al-buldān, vol. i, p.7. 13 Persians, and Turks had gone to war during the previous thousand years. 33 But the most outstanding factor that rendered this age illustrious in the world annals is the fact that it witnessed the most momentous intellectual awakening in the history of Islam. Historical records and legends are unanimous in placing the most brilliant period of the seat of the ‘Abbāsid caliphate. During the caliphate of Harun alRashid (145-193/763-809), though, not more than half a century old, the city of Baghdad had by that time grown from nothingness to a centre of exceptional wealth and international importance standing alone as the Byzantium rival. Then, Baghdad became a new symbolic center in political and religious terms and a city with no peer throughout the whole wide world.34 Another important area of focus that enhanced the historical writing at this period was the scholars’ responses to the increasing influence of adab, (a moral and intellectual training) and in doing so they were able to modify historical contents, forms and perspectives. This gradual shift took history to a new and more ‘secular’ environment. The early Muslim dogmatic view of the purpose of history writing was to obtain the pleasure of Allāh.35 But, the Qur’ān stressed the need of historical knowledge as a moral exhortation to the faithful. The Qur’ān says, ُ اَفَلَ ۡم َي ِس ۡی ُر ۡوا ِفی ۡاۡلَ ۡر ِ فَ َی ۡن َع َل ۡی ِہ ۡم ۫ َو ِل ۡل فک ِف ِر ۡين َ عا ِق َب ُۃ الَّ ِذ ۡينَ ِم ۡن قَ ۡب ِل ِہ ۡمؕ دَ َّم َر اللّٰ ُہ َ َف کَان َ ظ ُر ۡوا َک ۡی 36 َ ک ِبا َ َّن اللّٰ َہ َم ۡولَی الَّ ِذ ۡينَ فا َمنُ ۡوا َو ا َ َّن ۡال فک ِف ِر ۡينَ َۡل َم ۡو فلی ل ُہ ۡم َ اَمۡ ثَالُ َہا فذ ِل “Have they not travelled in the land to see the nature of the consequence for those who disbelieved before them? They were mightier than thee in power and (in the) traces (which they) left behind them in the earth. Yet Allāh seized them for their sins and they had no protector from Allāh”.37 33 Tayeb El-Hibri, Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography, p. 1. J. Lassner, The Shaping of Abbasid Rule, pp. 169-175; C. Wendell, Baghdad: Imago Mundi and Other Foundation Lore, pp. 99-128. 35 Al-Sakhawi, Al-E‘lan bi al-Taubikh li man Dhamma Ahl al-Taurikh, (Urdu) trans. Into English by Dr. Muḥammad Yusuf, p. 109. 36 Transliteration: Afalam yasīru fil arzi fa yanzurū kayfa kāna ‘āqibatullazīna min qablihim, dammarallāhu ‘alayhim wa lil kāfirīna amthāluhā, zālika biannallāha mawlal lazīna āmanū wa annal kāfirīna lā mawlā lahum. 37 The Qur’ān 47:11-12. 34 14 The basis of Qur’ānic storytelling is emphatically moral and spiritual. In other words, Allāh Almighty demands from us to look first and foremost at the moral aspects of a nation's history. It is obvious from the above cited verse that to look at history Islamically is to keep an eye on the moral, spiritual and ethical dimensions of all episodes in history, however big or small. Muslim historian were highly influenced by the worldview of rendering service to Islam by studying and writing history because, to them, the overriding aim of studying history is purely moral and ethical. While modern historians focus on different dimensions of history and offer different bases for the interpretation of history based on their respective belief systems, for instance the chief tenets of Marxists historiography are the centrality of social class and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. The main purpose of Muslims historian was to produce such a historical works which brought with it the political wisdom and conversational skill which assured success in this world and the humility and piety which assured blessedness in the other world.38 Due to Qur’ānic teachings Muslims have to learn as accurately and objectively as possible the facts of history so the Qur’ānic principles could be correctly applied, that is why we found Qur’ān had a correspondingly great influence not only on Muslims’ perception of history but also on Islamic historiography. The blink of an eye in the slow-moving world of ancient empires and tightly held traditions the political and religious landscape of the Mediterranean world was redrawn by ‘Arab Muslims, who were responding to what God had ordered them to do. Franz Rosenthal defines Muslim historiography in the History of Muslim Historiography: “Muslim historiography has at all times been united by the closest ties with the general development of scholarship in Islam, and the position of historical knowledge in Muslim education has exercised a decisive 38 Franz Rosenthal, A History of Muslim Historiography, pp. 60-61. 15 influence upon the intellectual level of historical writing....The Muslims achieved a definite advance beyond previous historical writing in the sociological understanding of history and the systematisation of historiography. The development of modern historical writing seems to have gained considerably in speed and substance through the utilization of a Muslim Literature which enabled western historians, from the seventeenth century on, to see a large section of the world through foreign eyes. The Muslim historiography helped indirectly and modestly to shape present day historical thinking.”39 Muslims certainly exported both historical material and historiographic forms. For example, that rabbis took up the ṭabaqāt scheme from their Muslim counterparts, and that well-placed Christians such as Theophilus of Edessa, the ‘astronomer royal’ of the caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775-785), wrote a history that drew, among other things, upon Islamic material.40 During the late first century hijrī writers such ‘Urwah bin al-Zubayr bin alAwwām al-Asadī (d. 94/713) and Muḥammad bin Muslim bin Ubaydullāh bin Shihāb al-Zuhrī (d. 124/742) began to assemble chronologies from the various word of mouth reports and scattered documents. Thus as time moved further away from Muḥammad’s days, Muslims grew increasingly interested in understanding their community’s past. During the second century hijrī (the eighth century CE) complete historical accounts begin to emerge. The earliest and most influential work was that of Muḥammad bin Ishāq bin Yasār bin Khiyār or simply Ibn Ishāq (85-159/ 704-770) whose work in the field of sīrah is considered as primary source. The original version of his work has been lost but Ibn Hishām (d. 218/834) fortunately edited it. 39 40 Franz Rosenthal, A History of Muslim Historiography, p.17. Chase Robinson, Islamic Historiography, p. 48. 16 Ibn Ishāq’s work on sīrah is the earliest complete biographical account to survive and dates to approximately 150 years or so after Muḥammad’s time. The late second and third centuries witnessed a further development in historical writing, with the growth of coherent and fluid narrative accounts. These histories tended to concentrate on a number of key topics. These included accounts of Muḥammad’s life, as well as treatments of the early conquests. Local histories were also written. The works pertaining to this era, accessible to us are The sīrah, or Life of Prophet Muḥammad by Ibn Hāshim, The section of the Annals of al-Ṭabarī dealing with the life of noble prophet (PBUH), The maghāzī or History of the noble prophet’s campaigns by al-Wāqidī, The ṭabaqāt of Ibn Sa‘d the secretary of al- Wāqidī.41 Abū Sa‘īd Abdul Malik bin Kuraib al-Asma‘ī (122-216/740-831) was the most eminent of all those who transmitted orally historical narrations, anecdotes, stories, and rare expressions of the language. Authored of Futūḥ al-salātīn, in which he discussed at length the biographies of the pre-Islamic rulers and kings and also mentioned the socio-cultural aspects of the Arabs and their civilization. But arguably the most important work from this period was that of Abū Ja’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī42 (224-310/839–923), who recognized as the father of Islamic history, one of the earliest, most prominent Persian historian and exegete of the Qur’ān. He became known primarily by his History. No study of medieval Islamic historical literature would be complete without considering him. He very often quotes his sources verbatim and traces the chains of transmission (isnād) to an original source. Chief virtues as a historian were his conciliatory and moderate approach, accurate chronology, scrupulous faithfulness in reproducing authorities and seeking harmonious agreement between conflicting opinions which earned him the respect of scholars and officials. Like Christian analysts, he depended on the 41 42 Syed Mahmud al-Nasir, Islam Its Concepts & History, p. 75. The adjective ending with the alphabet ‘i’ denotes a relationship of one kind or another, e.g., ‘al-Ṭabarī’, (geographic, ‘the person from Ṭabarīstān’, Note: The word Ṭabarīstan is derived from the Persian root word, ṭabar, which means land of the axe, so named because the early Muslim settlers there were forced to clear the woods with axes. For detail see Samānī, Ansāb, p. 39; Yāqūt, Mu‘jam, vol. iii, p. 503), Ḥanafī’ (academic, ‘the person who follows the legal thinking of Imām Abū Ḥanīfah’) and al-Hāshmī (Clan, the person from the clan of the Hāshim). 17 Hebrew Bible, though the world he inhabited was basically Egypt and Muslim Asia rather than Western Christendom. He wrote extensively on the topic of history, theology and Qur’ānic commentary. He wrote a universal history of the world which survives in a complete form entitled ( تاريخ الرسل والملوکTārīkh al-rusul wa al-mulūk), or History of Prophets and Kings, often referred to ( تاريخ طبریTārīkh-i Ṭabarī) which explores the history of the ancient nations, the prophets, the rise of Islam and the history of the Islamic World down to the year 302/915. It was completed in the year 350/961. It contains a host of earlier material not to be found elsewhere. It is renowned for its detail and accuracy concerning Muslim and middle Eastern history. By common consent this monumental and voluminous work (consists of 10 chapters and divided into 40 volumes of 200 pages each) considered as the most important universal history produced in the world of Islam. Al-Ṭabarī’s most extensive historical work is said to represent “the highest point reached by Arab historical writing during its formative period”. 43Among the many students who attended his lectures was famous historian of his time, al-Mas‘ūdī. An Arab historian and geographer, Abul Ḥasan ‘Alī bin al-Ḥusayn bin Ali al- Mas‘ūdī (283-345/896-956) was born into a family of Kufan origin which traced its pedigree back to ‘Abdullāh bin Mas‘ūd, a companion of the noble prophet Muḥammad (PBUH). He was a major figure in Muslim historical writing of the Middle Ages. He referred to as the Herodotus of the Arab by M. d’Ohsson,44 and was included in the list of the famous historian and traditionist like Abu ‘Ali Aḥmad bin Muḥammad bin Ya‘qūb bin Miskawayh (320-421/932-1030) and Abul Fazl Muḥammad bin Ṭāhir bin Aḥmad al-Shaybānī al-Maqdisī (448-507/10561113). Mas‘ūdī approach to his task was original: he gave as much weight to social, economic, religious and cultural matters as to politics. He authored substantial and major surviving historical work entitled مروج الذہب و معادن الجواہر 43 44 Muslim Writers on Judaism & the Hebrew Bible from Ibn Rabban to Ibn Ḥazm. p. 43. G. Sarton, in refereeing to al- Mas‘ūdī, spoke of “the Muslim Pliny”, while E. Renan compared him to Pausanias. Muslim Writers on Judaism & the Hebrew Bible from Ibn Rabban to Ibn Ḥazm. p. 46. 18 (Murūj al-zahab wa ma‘ādin al-jawāhir) or The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems which is divided into one hundred and thirty two chapters and was completed in the year 335/947 during the Buwayhid45 reign and was revised in the year 345/956. It is a work in which Mas‘ūdī combined pre-Islamic history, geography, astronomy, ethnography, the atmosphere, the earth, rivers and seas, the various regions of the world, the history of non-Muslim nations, and their religious beliefs, therefore, it could be called an encyclopedia of general culture. This classical world history is not the compilation of an armchair historian but the careful record of a man who actively pursued knowledge back to its sources. The range of Mas‘ūdī’s written sources is very extensive. It encompasses not only the well-known Muslim works on history, geography, astronomy, philosophy and theology but also a wealth of other, non-Muslim material.46 This book quickly became famous and established the author’s reputation as a leading historian. It is an historical account in Arabic of the beginning of the world starting with Adam and Eve up to and through the late ‘Abbāsid Caliphate. It is composed in a format that contains both historically documented facts, ḥadīths or sayings from reliable sources and stories, anecdotes, poetry and jokes that the author had heard or had read elsewhere. Due to its reliance on and references to Islam this style of history writing makes up an example of what constitutes Islamic Historiography in general. Khālidī states that Mas‘ūdī’s own observations form a valuable part of his work. And that In contrast to Ṭabarī, who provides little or no information on the lands and peoples of his own day, Mas‘ūdī often corroborated or rejected geographical and other data acquired second-hand.47 45 Bowayhids dynasty (322-454/934-1062), Islamic dynasty of pronounced Iranian and Shii character, represents native rule in western Iran and Iraq and dominated the Iranian politics for over 100 years. The founder of Bowayhids Dynasty is ‘Ali bin Buya, and originated from Lahijan in Dailam. Buwayhid dynasties took power in Fars (southwestern Iran, 934-1062); Rayy (366-420/977-1029); Jibal (320-419/932-1028); Kerman (324-440/9361048). From 333-447/945-1055, a Buwayhid dynasty ruled Baghdad and most of Iraq. 46 Mas‘ūdī, Tanbīh, pp. 154-155. 47 Khalidi, Tarif, Islamic Historiography: The Histories of Mas‘ūdī, p. 4. 19 Abul Fazl Muḥammad bin Ṭāhir bin Aḥmad al-Shaybānī al-Maqdisī (448507/1056-1113) or al-Muqaddasī, i. e., the native or inhabitant of the Holy City from Jerusalem, flourished in Bust, Sijistān in the early and mid-tenth century C.E. He was a Mathematician and astronomer. Author of encyclopedic dimensions, entitled ( کتاب البدع والتاريخKitāb al-bad‘ wal-tārīkh), or The book of the Creation and of History, a summary of the knowledge of his day based not simply on Muslim, but also on Iranian and Jewish sources. It was written around the years 355/966. 48 It is a historical treatise with strong theological overtones, which not only describes the history and doctrine of Islam but also compares it with other religions, including Judaism and Christianity.49 World map from Maqdisī’s work with the Kaaba as centre50 Muslim Writers on Judaism & the Hebrew Bible from Ibn Rabban to Ibn Ḥazm. p. 48. Theodore Pulcini, Gary Laderman, Exegesis as Polemical Discourse: Ibn Ḥazm on Jewish and Christian Scriptures, p. 38. 50 Taken from ; Gabriel Ferrand; Relations des voyages et textes geographiques.. .. livre de la creation et de l’histoire d’Abou-Zeid Ahmed Ben Sahl el-Balkhi. Publie et traduit par Cl. Huart - Maqdisi, Mutahhar bin Tahir, fl. 966. 48 49 20 Ghazan Khān (r. 694-703/1295–1304) commissioned to his vizier Rashid alDin (645-718/1247–1318) to write a history of the Mongols. During the reign of Oljeitu (r. 703-716/1304–16), this text was expanded into the (جامع التواريخJāmi‘ altawārikh) or Compendium of Chronicles the historical work composed in the period 1300-10. The Persian scholar, statesman and historian learned not only in history but also in theology, philosophy, and science. He composed a more truly Universal History or History of the World, which covered not only the Islamic world but also included data on the popes and emperors of Europe and on Mongolia and China. The breadth of coverage of the work has caused it to be called "the first world history". As its title suggests, the work is a compilation of materials not only on Islamic and Persian history, but also on the Mongols and other peoples with whom they came into contact: Turks, Franks, Jews, Chinese, and Indians. It was also considered one of the grandest projects of the Ilkhanate period (654-735/1256-1335)51, "not just a lavishly illustrated book, but a vehicle to justify Mongol hegemony over Iran. The heyday of historiography in Iran, however, was the Ilkhanate period and writing of history became a firmly established art in Iran and the adjacent Muslim countries. One of the most penetrating thinkers about historiography in any time or place was undoubtedly, Walī al-Dīn ‘Abd al-Raḥmān bin Muḥammad bin Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr Muḥammad bin al-Ḥasan Ibn Khaldūn (732-808/13321406), who was a master of religious learning, outstanding judge, writer on logic, astronomer, economist, historian, Islamic scholar, theologian, ḥāfiz, jurist, lawyer, mathematician, military strategist, nutritionist, philosopher, social scientist and 51 Genghis's grandson, Halāgu Khān (r. 654-663/1256–65) assumed the title of ill-Khan, meaning lesser Khan, subordinate to the Great Khan ruling in China. The Ilkhanid dynasty was based, originally, on Genghis Khan's campaigns in the Khwarazmian Empire in 1219–1224. It was established by Halāgu Khan in the 13th century and was to be ruled for seventy years by Halāgu and his descendants. This dynasty was based primarily in Iran as well as neighboring territories, such as present-day Azerbaijan, and the central and eastern parts of present-day Turkey. It was a breakaway state of the Mongol Empire, which was ruled by the Mongol House of Halāgu. For detail see Andre Wink, Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest 11th – 13th Centuries, vol. ii, p. 13. 21 statesman. He also considered as Father of Historical writing and modern philosophy of history and historiography especially for his historiographical writings in the Muqaddimah (Latinized as Prolegomena) and Kitāb al-‘Ibar (Book of Advice). The first detailed studies on the subject of historiography itself and the first critiques on historical methods appeared in the works of the Arab Muslim historian and historiographer Ibn Khaldūn. His intellectual legacy is unique and notwithstanding the lapse of centuries, still maintains its value, vigor and modernity and occupies a high place among the monuments of world thought. He developed one of the earliest non-religious philosophies of history. Arab historian Ibn Khaldūn’s masterpiece Muqaddimah (“Introduction”) reveals his ideas about history—something chroniclers hardly ever did. It is also held to be a foundational work for historiography. It is the most theoretically sophisticated programme of historical thought produced by any pre-modern historian, be the Christian, Muslim or otherwise. The subjects Khaldūn considered in his work include historiography historical method, philosophy of history, ecology, sociology, geography, demography, culture, economics, public finance, population, society and state, religion, politics, natural sciences of biology and chemistry and the social context of knowledge. In his muqaddimah he bitterly criticize the mistakes regularly committed by his contemporary historians and the difficulties which await the historian in his work. His historical method also laid the groundwork for the observation of the role of state, communication, propaganda and systematic bias in history, leading to his development of historiography. He also wrote a book entitled ( کتاب العبرKitāb al-‘Ibar)52, or “Book of Lesson”, is only an introduction to his large history or his general history. It is divided into three large books. (1) Society and its inherent phenomena, such as 52 The full title of this book is : کتاب العبر و ديوان المبتدا والخبر فی ايام العرب والعجم والبربر و من عاصرھم من ذوی السلطان اۡلکبر (Kitāb al-‘ibar, wa dīwān al-mubtadā wal khabar, fī ayyāmil ‘arabi wal ‘ajami wal barbari, wa man ‘āsirahum min zawīl sultān al-akbar) or Book of Lessons, Record of Beginnings and Events in the history of the Arabs and Berbers and their Powerful Contemporaries. 22 sovereignty, authority, earning one’s livelihood, trades, sciences, and causes and reasons appertaining to them. (2) History of the Arabs, their generations and dynasties from the creation to the present time, containing the annals of some of the contemporary nations and great men and their dynasties, such as the Pontains, the Syrians, the Persians, the Jews, the Copts, the Greeks, the Romans, the Turks and the Franks. (3) The history of the Berbers and tribes appertaining to them, such as the Zanata, their origin and generations, and their kingdom and dynasties in North Africa.53 Late in his life he had the opportunity to discuss history with the Mongol emperor Timur the Lame, who was besieging Damascus. Timur wrote his own memoirs, and he was evidently interested not only in what Khaldūn knew about North Africa but also in his philosophy of history. Jamāl al-Dīn Abī al-Ḥajjāj, Yusūf bin ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Mizzī (654743/1256-1342) was an Islamic scholar, who authored a book entitled تہذیب الکمال فی ( أسماء الرجالTahzīb al-kamāl fī asmā al-rijāl) which contains the biographies of 8,640 narrators, including Companions, punctuated by places and countries of origin of the reporters. The names of the biography subjects are arranged in alphabetical order in contrast to the original work. Muḥammad bin Aḥmad bin Uthmān bin Qayyūm Abū ‘Abdullāh Shams alDīn Zahbī (673-748/1274-1348), a historian of Islam. He authored nearly 100 works, some of them of considerable size. Few famous works among them are Tārīkh al-Islām al-kabīr (Major History of Islam); Siyar a‘lām al-nubalā (Lives of the Elite of the Nobility), twenty three volumes, a unique encyclopedia of biographical history; Tahzīb tahzīb al-kamāl, an abridgement of al-Mizzi's abridgement of al-Maqdisī’s al-Kamāl fī Asmā al-rijāl, a compendium of historical biographies for ḥadīth narrators cited in the six major ḥadīth collections [The two Ṣaḥīḥs and the four sunan]; Tazkirat al-ḥuffāz (The memorial of the ḥadīth masters). 53 Muḥammad ‘Abdullāh Enan, Ibn Khaldūn His Life and Work, p. 151. 23 Renowned scholar, Abul Fidā Ismā‘īl bin ‘Umar bin Kathīr (701-774/13001373) is considered as one of the most authoritative sources on Islamic History. He authored the famous Encyclopedia of Islamic History, viz, al-Bidāya wal nihāyah (" )البداية والنهايةthe beginning and the end" is one of the best-known works of Islamic historiography. This invaluable historical work is considered to be one of the most authoritative and comprehensive sources on Islamic history. As per the words of Ibn Kathīr himself, he compiled history of mankind starting from the creation of universe, creatures and everything in or out of it. It is an excellent reference on the history of the prophets, sīrah, the history of early Islam, the history of Sham, Iraq and history up to time of author, i.e., eight century hijrah (fourteenth century CE).54 Its primary value is in the details of the politics of Ibn Kathīr’s own day. The Mamlūk era (648-923/1250-1517) is also distinguished by having produced a core of literature, so to speak, on historical thought and theory, a genre that set the stage for the later development of Muslim historiography in general.55 Under the Mamlūks, Cairo became a major intellectual and artistic center and grew into arguably the largest city in the region. During the Mamlūk period, Arabic encyclopedic literature was at its peak in the scholarly centers of Egypt and Syria. Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad bin ‘Abdul Wahhāb al-Nuwayrī’s (d. 733/1333) Nihāyat al‘arab fī funūn al-adab (The Ultimate Ambition in the Branches of Erudition), a 31volume encyclopedic work composed at the beginning of the 14th century and divided into five parts: (i) heaven and earth; (ii) the human being; (iii) animals; (iv) plants; and (v) the history of the world. In the fifth book on history, where single chapters swell to the size of entire volumes, al-Nuwayrī introduces a form of textual navigation that seems to have been unprecedented in Islamic historiography. Rather than structure this fann according to the widely prevalent annalistic arrangement, he opts for a different method, which he outlines in the preface to Book V: 54 A unique feature of the book is that it not only deals with past events, but also talks about future events mentioned by the noble prophet Muḥammad (PBUH) until the Day of Judgment. 55 Franz Rosenthal, A History of Muslim Historiography; see also Khalidi, Historical Thought, chapter 5, History and siyāsah. 24 “When I saw that all those who wrote the history of the Muslims had adopted the annalistic form rather than that of dynastic history, I realized that by this method the reader was being deprived of the pleasure of an event which held his preference and of an affair which he might discover. The chronicles of the year draw to a close in a way which denies awareness of all the phases of an event. The historian changes the year and passes from east to west, from peace to war, by the very fact of passing from one year to another ... The account of events is displaced and becomes remote. The reader can only follow an episode which interests him with great difficulty... I have chosen to present history by dynasties and I shall not leave one of them until I have recounted its history from beginning to end, giving the sum of its battles and its achievements, the history of its kings, of its kingdom and of its highways.”56 The famous historian Ibn Khaldūn (d. 808/1406) used it as a source for his own history.57 The writing of history continued to be a normal feature of Muslim civilization in the more advanced Islamic societies. In several countries, notably in parts of India, the first works that deserve the name of history appeared only after the Muslim conquest or the conversion to Islam. After the 12 th century Arabic ceased to be the main language of Muslim historiography. Distinguished histories were written in Persian in the 13th century, and subsequently Turkish and other vernaculars came to be used by historians in different parts of the Islamic world. But, in its isolation from non-Muslim influences and its traditional interests, Islamic historiography underwent no intrinsic change until the 19 th century, when it began to be affected by the impact of modern Western civilization. Donald P. Little, “The Historical and Historiographical Significance of the Detention of Ibn Taymiyya,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 4 (1973), p. 315 57 For Ibn Khaldūn’s debt to the Nihaya, see Donald P. Little, An Introduction to Mamluk Historiography: An Analysis of Arabic Annalistic and Biographical Sources for the Reign of al-Malik an-Nasir Muḥammad bin Qalaun, p. 96. 56 25