Colonial Planning in Africa: Tanzania, South Africa, Ghana

advertisement

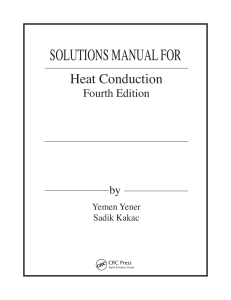

5 COLONIAL PLANNING CONCEPT AND POST-COLONIAL REALITIES The Influence of British Planning Culture in Tanzania, South Africa and Ghana Wolfgang Scholz, Peter Robinson and Tanya Dayaram Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Introduction The British Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 was adopted in many British colonies and even updated versions of the legislation retained the major features in several countries (cf. Payne, 2001). Land use planning standards including land use zoning were based on the model of a low density, green city that reflected the ideals of a colonial version of the Garden City combined with ideologies of a city’s sanitation and health concerns. This concept may have been adequate for colonial towns with modest growth that were physically and socially contained through restrictions of rural-urban migration. However, it cannot cope with the high urban growth rates since independence and, above all, it cannot be implemented by weak public administrations with limited resources (cf. Ambe, 1999; Payne, 2001). Furthermore, it is hardly suitable for the current process of urbanization under poverty where the majority of settlers can only afford small plots and where large plots in planned areas lead to high costs for infrastructure supply (Kombe, 2011). Many countries still use a masterplan approach although it is not suitable to guide rapid and mostly informal urban development. Despite having decentralization processes on the political agenda, in many countries it is not functioning well since local authorities lack funds and qualified staff to perform their given duties. This chapter looks at three different countries in Africa (Tanzania, South Africa and Ghana) which all share a British planning system and analyses processes of adaption and transformation in the current planning legislation and implementation. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 68 Wolfgang Scholz et al. The Planning System and Legal Framework in Tanzania In Tanzania local government units are district authorities and town authorities. The district authorities include the district council, township authorities and village and Mtaa (sub-ward) governments. These are the administrative institutions with full mandate for land use planning in their areas. However, central government institutions control and approve local planning schemes. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. TABLE 5.1 Administrative levels and Spatial Planning Instruments in Tanzania Level Size National 44,928,923 Central people (2012) Government: 963,000 km² Ministry of Planning Regional 30 regions, size from ca. 330 km² to ca. 68,000 km² District – Rural 169 districts, size from ca. 28 km² to ca. 45,000 km² Institution Spatial Planning Instruments Description National plans: Long-term, 5-year annual plans and annual budgets Expenditure plans for different sectors, infrastructure and socioeconomic development. Allocation of funds to different ministries and regional authorities. Expenditure plans for different sectors and for infrastructure and socioeconomic development within the region. Allocation of funds for different sectors. Addressing spatial development problems in the region. Location and development of settlements, including hierarchy of centres. Guiding the provision of services and social infrastructure. Guiding public sector agencies in locating projects. Budgeting and allocation of funds to different sectors in the district. Central Government: Prime Minister’s office for Regional Administration and Local Government (PMO-RALG) Regional plans and Regional Integrated Plans (RIDEPS): socio-economic and infrastructure planning Division of Human Settlements, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD) Regional physical plans, district, municipal, village development plans District Council under direct supervision of PMO-RALG Division of Human Settlements represented in the district by the respective District Town Planning Office District Annual Development Plan District Physical Identifies priority Plan sector and projects for investment. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 69 Level Size Institution District – Urban Different categories: City: >600,000 inhabitants Urban councils Annual Development under direct Plan supervision of PMO-RALG in respect of spatial plans Municipality: >80,000 inhabitants Town: >30,000 inhabitants Township: >9,000 inhabitants >250 families Division of Human Settlements represented by the Municipal planning office District – Village Village Council approved by the District Council Directorate of Human Settlements Development Spatial Planning Instruments Description Budgeting and allocation of funds to different sectors in the urban district/council. Identifies priority sector and projects for investment. Land use planning General schemes dealing with Planning Scheme (master residential, commercial, industrial, recreational, plan, interim land use plan or open spaces, agriculture, strategic urban institutional, and so on. development plan – SUDP) Village Development Plan Village Land Use Plan Registration by the Regional Administration and Local Government. The plan deals with land resources assessment and shows how the village land should be used. Main land uses are: farms, grazing areas, forest, residential, sites for community services, roads, and so on. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. (Source: Burra and Kyessi (2008, p. 159), modified and updated by the authors) In Tanzania, the British Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 was adopted via the Town and Country Planning Act of 1956, Cap 378 and it is still the main legislation for urban planning in Tanzania. It covers the following land use planning related issues: • • • • • • use of land and buildings; intensity of use of land and occupancy rate; size, form and construction materials of buildings; siting of buildings; alignments and reservation of land for roads and other physical infrastructure; and preservation of natural and man-made features as well as regulating and controlling disposal of refuse and pollutants. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 70 Wolfgang Scholz et al. Concerning the planning processes and actors involved it defines: • • • • the procedures for declaring planning areas; the contents of planning schemes and their twofold nature (general and detailed plans); who will prepare and approve plans and the relationship among involved actors; and procedures for development control. Land use planning is also regulated through technical and administrative guidelines issued by the Directorate of Human Settlements Development and by-laws formulated by the respective local authorities. Local authorities are responsible for plan preparation while the Minister is responsible for approving plans. Table 5.2 provides an overview of the spatial planning related legal framework. After independence in 1961, the colonial planning standards were modified but with little attention to post-colonial socio-economic realities. The 1956 Town and Country Planning Law was only recently reviewed (Urban Planning Act, 2007) but by and large the contents have remained the same. The internal draft for the recent revision of plot size standards is far beyond what urban poor dwellers can afford, it does not support sustainable and compact urban development or optimal use of scarce resources including public finances for basic infrastructure services (Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, 2011: see Table 5.3). Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. TABLE 5.2 Planning-related legislation in Tanzania Year Planning Legislation 1956, as revised in 1961 1964 Town and Country Planning Ordinance Cap 378 Government Notice Nº 678 of 4th December 1964: Modification of Planning Schemes Regulations Local Government (Urban Authorities) Act no 8 National Land Policy National Environmental Policy Town and Country Planning Ordinance (Town Planning Space Standards) Regulations Regional Administration and Local Government Act Land Act no 4 Local Government (urban and district) Act no 6 National Human Settlements Development policy The Town and Country Planning (Urban farming) Regulation National Transport Policy Environmental Management Act Unit Title Act 1982, as revised in 1999 1995 1997 1997 1997 1999 1999 2000 2001 2003 2004 2008 (Source: Burra and Kyessi (2008, p.158), updated by the authors) Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 71 Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. It still reflects colonial concepts of a Garden City and low densities due to sanitation and health reasons. Current urban land use planning standards still require large plot sizes that are too expensive for the Government to service and unaffordable by most social groups, especially the urban poor. Kombe (2011) highlighted the costs for different infrastructure standards in relation to plot sizes. He concluded that for the stipulated plot sizes, infrastructure costs would be prohibitive. This reduces the ability of local government to fulfil its obligations of service delivery and contributes to the shortage of building land. The cost of basic infrastructure services in comparison to full service infrastructure (e.g., including private water pipes and sewage) only doubles in the case of small plots of 100 m². However, for larger plot sizes, e.g., according to the official land use planning standards (min. 400 m², see Table 5.3), the costs increase by more than three times. This is mainly due to the increased total length of infrastructure service lines such as roads, water pipes, storm water drains, and so on, in relation to the number of costumers or households being served. The unmet demand for affordable building land is thus largely covered by the informal land supply system which operates with average plot sizes of about 100–200 m². It can thus be argued that inappropriate planning standards, especially the plot sizes, have compounded the problems of urban governance, mushrooming informal settlements and the absence of basic infrastructure services even in most of the new planned and surveyed areas (authors’ fieldwork, 2011). For decades, there has been hardly any planned residential settlement in Dar es Salaam that meets the needs for low-income groups. Even areas planned and designed for the urban poor (so called high-density areas), where plots were offered below market prices, did not reach the target groups because they could not afford the land prices requested or were bypassed in the allocation process. In some cases, rising land prices even forced residents to sell allocated plots (authors’ fieldwork, 2010). TABLE 5.3 Proposed revised plot size standards (current standards are in brackets) Density Plot size in (m2) High Medium Low Super low (new category in the draft) 300-600 (400-800) 601-1200 (801-1600) 1201-1600 (1601-4000) 1601-2500 Maximum Maximum Minimum Minimum Minimum coverage plot ratio setbacks front setbacks side setbacks rear (%) (m) (m) (m) 40 0.4 3 1.5 30 (25) 25 (15) 20 0.3 (0.25) 0.25 (0.2) 0.2 3 3 5 4 7 7 1.5 (2) 3 (5) 5 (10) 7 (Source: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, Internal draft 2011, not published) Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. 72 Wolfgang Scholz et al. An initiative of the Government of Tanzania (Dar es Salaam 20,000 Plots Project) which aimed at providing planned, surveyed and allocated plots to reach all income groups has failed due to high service costs, disadvantageous locations and non-transparent allocation procedures (Kombe and Kreibich, 2007, p.157). In many locations of the 20,000 Plot Projects, prices for plots skyrocketed from an initial average of TSh 400,000 (1 € = 2,100 TSh in October 2013) for a high density plot (charged by the Government upon allocation) to TSh 5 million (price in the land market) in less than five years. This is more than ten times the official price charged and reflects the development of land prices for surveyed areas (authors’ fieldwork, 2011). Most of the urban poor, therefore, can only find a place for living in the informal settlements where they can access smaller plots at affordable prices for land that is not serviced. In exchange they will have to cope with higher costs for services and utilities like urban transport and water from street vendors. The lack of buildable land provided through the formal system has also increased the development pressure on existing settlements. The growing commercial and service sector in the current market-led economy has given rise to land use changes towards commercial activities in residential areas. Many property owners are changing their houses to accommodate economic activities such as shops, offices, and workshops due to higher rent expectations. Land use changes from residential to commercial activities are taking place since plots for commercial activities are not sufficiently available on the land market due to an insufficient designation of plots for commercial activities in former and current planning schemes (author’s fieldwork, 2011). Another aspect of the pressure on land is the redevelopment of plots with multi-storey buildings following increased land values. While this development tends to support a more compact city, most construction activities under redevelopment ignore the need for adequate setbacks, leading to inadequate space between buildings. The planning standards in Table 5.3 do not consider multistorey constructions and their higher demand for setbacks. They were designed for single-storey buildings as the dominant type during colonial times and do not deal with floor ratios or setbacks in relationship to the height of the building (authors’ fieldwork, 2010). These facts show the need for re-thinking central elements of the statutory land use planning system focusing on the increasing pressure on land, the need to guide urban development effectively, to create more functional settlements, to assist the urban poor to access affordable building land, and to release financial assets for the urban economy. The Act is currently under review to take into account key socioeconomic changes, particularly the large unplanned parts of cities which could not be governed by the existing instruments and management practices that are in force. However, it is not expected to change the general underlying concepts of colonial legislation and urban models. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 73 Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Planning procedures in Tanzania There have been some changes in the urban planning system during the last two decades. The planning system is changing from a rather technocratic to a more participatory and strategic planning approach. Also it is intended to involve more stakeholders and to follow a bottom-up approach by introducing Environmental Planning and Management (EPM) at municipal or district level. Planning has changed from strict master planning to a more flexible strategic planning approach. The aim is to integrate unused capacities at the grassroots level to supplement the role of public administrations in defining and achieving strategic urban development objectives. As far as possible it needs to incorporate local administrative institutions and locally-based conflict resolution mechanisms. Efforts to depart from the present approach to a local and community based planning and management of change are however made through international donor-funded programs. UN-Habitat facilitated implementation of a program on sustainable urban development planning (Sustainable Cities Programme, SCP) in ten municipalities, including Dar es Salaam. It involves demand-based planning and execution of projects with local communities, taking as point of departure the inhabitants’ own initiatives and resource capacities. The success of such efforts, nevertheless, requires changes within the institutional framework for planning to, inter alia, empower communities, facilitate, and enhance their initiatives, rather than mere controls and prescriptive form of planning. The Sustainable Dar es Salaam Project (SDP) was one example being implemented in Tanzania from 1993 to 1999. Its main objective was to strengthen municipal planning and management capacity and improve the participation of stakeholders in the urban management needs of the city. With the launching of the SDP, a collaborative planning approach – the strategic urban development planning – was initiated and adopted within the planning system. This was a new form of planning which reflects the process view of planning. It employs the participation of more actors than just experts from outside. It focuses on participation of stakeholders and communities in managing issues of their concern. The strategic urban development planning is seen as a realistic approach in providing solutions to urban problems rather than the use of master plans that are difficult to implement. In order to improve on the traditional master planning approaches, and in addressing the continuously complex urban development processes, this approach adopts a more dynamic, continuous and consensual vision building and policymaking process. The output of the strategic planning process is not just a physical development plan for the city but a set of interrelated strategies aimed at enabling all public, private and community initiatives to promote economic growth, provide basic infrastructure services and enhance the quality of the environment. These and other new approaches have thus attempted to move away from the rigid formality of blueprint urban master plans. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 74 Wolfgang Scholz et al. While the SDP experiment can be seen as a success story (despite its dependency on donor funds for the extensive stakeholder involvement), its planning output has not been approved by the Ministry. The planning document of SDP provides options for future development and sets preferences for land uses according to suitability criteria only. The Ministry, however, expected a comprehensive future land use plan and no open final decisions on future land uses. This conflict between process orientated flexible planning and the demand of the authorities for a final land use plan led to the development of new general planning guidelines: “combining the advantages of both” (Lupala, 2013). Today in Tanzania, both general planning schemes, like a Strategic Urban Development Plan, and detailed planning schemes have to follow documented stakeholder meetings on the one hand and produce planning documents with defined future land uses on the other. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Critical review While in theory, the planning approach has changed to a more participatory one, there is a need for a deeper look into the reality of implementation on the ground. The change towards a free market economy in the 1990s had implications on spatial planning and land use policies. However, the “failure to [adjust the legislation] made the 1956 Planning Ordinance irrelevant for guiding settlement development” (Burra and Kyessi, 2008, p.161). Furthermore, there is “no evidence of satisfactory grass-root participation in local planning and management of development” (Burra and Kyessi, 2008, p.161). Planning practice is still dominated by the Ministries of the central government. Recently enacted laws and national policies tried to establish links with the local and grass root institutions (see Table 5.2): The Local Government (Urban Authorities) Act (1982); The Regional Administration and Local Government Act (1997); The Local Government Reform Agenda (1996–2000); The National Land Policy (1995) and The Land Act (1999). These acts aimed at empowerment and mobilization of local communities in planning and managing land. However, as Burra and Kyessi stated: “The law requires that planning schemes are deposited for public examination in a period of three months before they are approved by the Minister. This is rarely done with respect to general planning schemes and never with regard to detailed planning schemes. In the past, this practice deprives residents of their democratic right to contribute in shaping the built environment, and the legal opportunity to participate in the planning process to safeguard their interests in land and property development.” (2008, p.161) All urban settlements with populations above 30,000 have today a general planning scheme but approved village land use plans exist only for few villages and “most of Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 75 these plans, particularly village land use plans are rarely implemented or land use change decisions followed up” (Burra and Kyessi, 2008, p.161). There is also lack of awareness of planning regulations in institutions at the grassroots level of the Government (Mtaa, ward level). For instance, in the sub-ward office (Mtaa) of Sinza, Dar es Salaam, the copy of the land use and layout plan was missing. It seems that in the understanding of residents as well as local leaders, planning only focuses on the change of land use at the plot level, approved individually by the local leaders, and not according to the general or detailed planning scheme. Thus individual decisions do not correlate to the existing plans or general regulations. Permissions to build, extend or to change the use of a building are issued by local leaders mostly based on the political influence of the applicant overruling a planner’s technical statement and thus in disregard of public interests. Therefore, conflicting land uses easily emerge. Such permissions focus only on the plot itself, and ignore the neighbors’ plot and the construction on it (concerning size, height, setbacks and land use) (authors’ fieldwork, 2012). It can be summarized that the economic as well as political changes declared through liberalization policies have not been incorporated sufficiently in the planning system or practice and the participation of stakeholders is still limited. Impact of Planning Practices in South Africa Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. This section discusses aspects of Town Planning legislation which have (or should have) had an impact on urban structure and form of settlements for low-income people in South Africa since the mid-twentieth century. In order to provide a sharp focus, the emphasis will be on the province of Natal (later called KwaZuluNatal). South African planning legislation has evolved through three phases: • • • Early foundations (up to 1990) Transition (around 1990 to 2000) Contemporary (from 2000 to 2013) At various stages, Natal has led the way in changing town planning legislation and practice in South Africa; examples include: the establishment of the Town and Regional Planning Commission in 1951; the Package of Plans in the 1980s; early experiments with integrated development planning in the 1990s; and the Planning and Development Act of 2008 (see Table 5.4). Early foundations (up to 1990) During the early and middle of the twentieth century, town planning legislation in South Africa was strongly influenced by English Town and Country Planning Acts. In particular, the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act was the foundation upon which most of the Provincial Town Planning Ordinances were formulated. In the Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. 76 Wolfgang Scholz et al. South African context, it is significant that the apartheid era dates from the 1948 general election in which the Nationalist Party came to power. For example, the Natal Town Planning Ordinance set out to “consolidate and amend previous laws relating to the establishment of townships, the sub-division of land, layout of land for building purposes or urban settlement and the preparation of town planning schemes” (RSA, 1949, p. 1). During the second half of the twentieth century successive changes in emphasis in UK Town Planning law and practice (such as the advent of Structure Plans after 1968) were reflected in adjustments to South African town planning legislation and practice. The influence of USA and European town planning can also be traced from about the 1960s. The standards and norms used in the planning and development of the low-income settlements and townships that were formulated in the 1950s remained the cornerstone for the next 40 or so years, with no more than minor adjustments. Throughout this first period, settlements and townships for low-income people were planned and developed by the public sector (mainly central government but also by some of the large municipalities). The most influential guidelines were a book published in 1951 by T. B. Floyd entitled Guidelines for Township Layout; and the NBRI’s (1983) Guidelines for the Provision of Engineering Services in Residential Townships which provided local authorities with a set of standard guidelines on infrastructure design service and provision for residential townships. Subsequent revisions were known as the Red, Brown and Green Books. Neither the guidelines nor the standards proposed in these documents were legally enforceable but were widely used in practice (Behrens and Watson, 1996, pp. 30–32). Examples of the type of urban form that resulted are large urban townships such as Soweto and KwaMashu, situated on the then outer fringe of Johannesburg and Durban respectively, other large, more remote townships such as Botshabello (56 km from Bloemfontein), Madadeni (24 km from Newcastle) and many smaller townships located between 5 and 10 km away from the towns on which they depended for services and facilities. These so-called townships were planned according to the British master plan New Town model. The urban form was characterized by uniform plot sizes of 280–300 m² for free-standing houses which were known as NE 51 – short for Non-European 1951 – typology of houses. The two dominant types were 41.4 m² and 51.2 m², three-room houses with external or internal toilets. This lot size determined the density of formal townships for Africans throughout the country. The advent of informal settlements began during the mid-1970s as people began leaving the black rural Homelands and started migrating into the edges of towns and cities in the so called “white areas”. The first phase continued until around 1990 when the watershed changes in the South African political scene began to gain momentum in the early 1990s. Table 5.4 provides a timeline summary of these changes together with the case studies selected to show how legislation and guidelines from each period worked out on the ground. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 77 TABLE 5.4 Timeline of legislation and examples of urban housing projects Year Legislation/guidelines 1947 1948 1949 1951 1951 UK Town and Country Planning Act Nationalist Party in power in SA Natal Town Planning Ordinance 27 Group Areas Act T. B. Floyd’s Guidelines for Township Layout 1952–1970s Building of large townships for African, Colored and Indian citizens Development of Soweto (between 1950 and 1960) KwaMashu (completed 1970) 1957–1971 1962 From mid-1970s 1976 1976 1983 1986 1988 1990 Event/project Proclamation 293 Informal settlements start emerging around most large cities and towns Urban Foundation established SAICE / SAITRP guidelines on the planning and design of township roads and storm water drainage Blue Book – Guidelines for the Provision of Engineering Services in Residential Townships Repeal of Group Areas Act Green Book Announcement of unbanning of ANC Nelson Mandela released Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. (Source: authors) Transition phase (1990 to 2000) As it became apparent that a new era was in the making, progressive Town Planners and other built environment professionals began to take the opportunity of impending changes in legislation across the board to shake off the shackles of what were regarded as overly rigid and inflexible town planning legislation with associated regulations and practice guidelines. Thus began a decade of formulating new approaches to settlement and township planning. It was a time when new legislation was being formulated and innovative approaches to settlement development were being tested on the ground. In two significant cases, interim legislation was introduced to manage settlement development during the period when old legislation was being replaced. The Less Formal Townships Establishment Act (RSA, 1991) and the Development Facilitation Act (RSA, 1995) both aimed at speeding up the urban development process with a particular focus on poor communities. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 78 Wolfgang Scholz et al. The underlying principles of the DFA formed the basis for changes to planning legislation in the contemporary period (see the text box below). Development Facilitation Act (RSA, 1995) Principles a. b. c. d. e. f. g. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. h. Promote the integration of the social, economic, institutional and physical aspect of land development; Promote integrated land development in rural and urban areas in support of each other; Promote the availability of residential and employment opportunities in close proximity to or integrated with each other; Optimize the use of existing resources including such resources relating to agriculture, land, minerals, bulk infrastructure, roads, transportation and social facilities; Promote a diverse combination of land uses, also at the level of individual erven or subdivisions of land; Discourage the phenomenon of urban sprawl in urban areas and contribute to the development of more compact towns and cities; Contribute to the correction of the historically distorted spatial patterns of settlements in the Republic and to the optimum use of existing infrastructure in excess of current needs; and Encourage environmentally sustainable land development practices and processes. Other innovations related to informal settlement upgrading included, for example, the adoption of integrated approaches to planning at urban and regional scales; new institutional arrangements for delivery; and new forms of urban development finance; and a more flexible approach to planning and standards (see the text box below on “Innovative planning and urban development practices in the Transition Phase”). Innovative planning and urban development practices in the Transition Phase • • Adoption of integrated approaches to development planning at regional, sub-regional and local scales. Institutional/delivery agencies such as Independent Development Trust, Cato Manor Development Association and the housing companies set up under the auspices of the Urban Foundation. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 79 • • • • • • • • • Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. • • • Large-scale urban reconstruction as in Cato Manor which became the crucible for innovation with a view to replicability. Urban development finance arrangements facilitated by the State Presidential Projects and the European Union. New forms of housing finance including capital subsidy. Informal settlement upgrading – For example, Besters Camp. Recognition of the need for Project Preparation as an explicit element of the process of linking poor communities to the funding sources becoming available from government and international donor agencies. The Project Preparation Trust was set up in 1993 to fulfil this need and remains in full operation to date. Negotiated standards and norms for infrastructure, services e.g. in Wiggins West Fast Track in Cato Manor where Housing Support Centre assisted residents to use their subsidy funding effectively. Clustering of public facilities (primary and secondary school, sports fields, a community hall and a library) on 2 ha sites in Multi-Purpose Community Centres built in Cato Manor made multi-purpose trips possible. “The approach has a significant impact socially, visually and by clustering, set preconditions for an integrated approach to the management of the facilities thereby reducing operating costs” (Dewar and Kaplan, 2004, p.66). KZN province developed a Manual (TPI, 2008a) Guidelines for Planning of Facilities in KwaZulu-Natal. More flexible forms of planning such as spatial concept plans, precinct plans and spatial development frameworks and capital investment frameworks, as well as recognition of the value of mixed use areas, nodes of different scale and character and development of different types of movement corridors. New approaches to layout planning as advocated by Behrens and Watson in their handbook Making Urban Places (1996). Involvement of a variety of stakeholders in land and housing development processes. Ascendency of planning and development advocacy organizations (such as the Built Environment Support Group in Durban and Pietermaritzburg, Planact in Johannesburg, Development Action Group in Cape Town and Coreplan in East London). The Urban Foundation was a highly effective policy think-tank and implementation facilitator. The second phase continued until 2000 when a major demarcation process changed the municipal and planning legislation landscape. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 80 Wolfgang Scholz et al. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Contemporary phase (from 2000 to 2013) In December 2000 the Municipal Systems Act came into effect marking the beginning of the contemporary era. This Act gave legal form to the integrated approach to development planning that had evolved through practice in the transition phase. The contemporary phase may be characterized by the new form of plans, called Integrated Development Plans (IDP), Spatial Development Frameworks and Land Use Management Plans, which started replacing older types of plans such as Structure Plans and Town Planning Schemes. All municipalities were required by law to produce an IDP in 2002 and to review this under provincial supervision every 5 years. The last decade has witnessed significant delivery of housing, basic services and facilities to the poor. Between 1994 and 2010 the housing program had constructed some 2.4 million RDP houses nationally. The proportion of Africans living in formal housing has risen from 53% in 1996 to 71% in 2011, and there are now more than 5.8 million African households who own their own homes, the majority of them outright without owing any money on them. The transfer of title deeds to occupants of township housing (by 2001 over 300,000 houses had been transferred), as well as the RDP housing is partly responsible for this trend. Over half of all African households now have a flush toilet, up from a third in 1996, and the majority of African households use electricity for cooking and lighting, which used not to be the case (Holborn, 2013, p.3). At the same time there have been a number of shifts in policy in response to lessons from the ground. In the early 2000s, for example, the South African housing policy had been strongly criticized for supplying standardized products to individual beneficiaries instead of supporting communities to progressively resolve their housing problems (Khan, 2003, pp. 77–84; Baumann, 2003, pp. 85–114). In response a new national housing policy called Breaking New Ground was introduced. It re-emphasized guiding principles of the DFA and recognized the potential of housing development as a means of spatial restructuring. The policy introduced new instruments such as additional funding for the purchase of welllocated land, higher subsidies for social housing in restructuring zones, and a program for upgrading informal settlements. As a result, there has been an increase in delivery of social housing. Another important policy shift occurred around 2010, when the terminology and emphasis shifted away from slum eradication to a more progressive and incremental approach to upgrading of informal settlements. About the same time the names of national and provincial Housing departments were changed to Human Settlement indicating a more holistic perspective. In 2011, eThekwini (metropolitan Durban) municipality embarked on an innovative program to provide interim services in informal settlements which are neither on the short-term program for upgrading nor located in dangerous places such as floodplains and unstable land. New planning legislation has been introduced during this phase. The Planning Profession Act (RSA, 2002) led to the re-establishment of a statutory organization Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 81 responsible for regulating the planning profession. SACPLAN is currently reviewing the competencies and standards for planners, accreditation processes for Planning Schools and professional registration procedures. It is still too early to assess the effects of recent legislation such as the KZN Planning and Development Act (RSA, 2008) and Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (RSA, 2012) on settlement and urban form. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Lessons from South Africa The South African experience between the early 1950s and early 1990s was one of little more than small changes in the planning legislation and the guidelines used by practitioners for township layout and the provision of infrastructure services, as well as delivery of houses. Since then there have been a number of changes in the underlying planning philosophies and a plethora of new legislation. However, this has not always led to much change on the ground. The urban form of Welbedacht (an RDP housing project started in 2000) is very similar to that of KwaMashu in the late 1960s. That said, it is clear that the KwaMashu of 2012 (over 50 years old) is a far better performing settlement than it was in the 1960s. In part this is due to the growth of the metropolitan area to the north and the improved accessibility to jobs and public transport; in part it is the result of large numbers of small and sometimes bigger efforts and investments by the residents to customize their settlement to their needs. Most of these efforts have been informal; not all have been positive. Two of the better examples of settlement development are Besters and Cato Manor. In both cases, these were developed by innovative institutions (IDT and CMDA), using enabling legislation (LEFTEA) that was not too prescriptive and involved extensive facilitation by the development agencies to engage the community, local authority and contractors about standards and end product. The enabling legislation has recently been replaced by permanent new planning legislation. Looking back over the contemporary phase there are a number of distinct improvements, as well as some areas of concern. The improvements include: • • • • a uniform system of planning for all areas, urban and rural; an explicit developmental focus with emphasis on service delivery; linking of the integrated development plans to budgets of municipalities and service providers; increased community participation in the planning process. The main concerns are: • that the very sophisticated planning system which has been introduced will be difficult to implement on account of limited human resources and institutional infrastructure; Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 82 Wolfgang Scholz et al. • • • that the duality which exists between formal and informal systems in almost all facets of development may not have been adequately catered for; that planners and administrators of planning procedures will experience difficulty in making the adjustment to the new forms of planning; and that the municipal demarcation and form of planning will be subject to further changes. One lesson arising from this is that appropriate planning legislation and procedures are necessary but not sufficient conditions for creation of well performing settlements. Suitably resourced and capacitated development agencies are a vital ingredient. Another lesson is the huge advantage of having enough flexibility in the operating environment to allow scope and capacity to negotiate about allocation processes, levels of services and built forms. Many of the changes have resulted from initiatives and programs far wider than planning legislation. However, planning has played a significant role which suggests an emerging awareness of the role of planners in the interface zone with the work of other built and natural environment and development professionals. Decentralization in Ghana: Theory and Practice Similar to the two examples above, the planning legislation in Ghana is based on the British planning system and planning culture (Figure 5.1). The Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD) which is still in place was established in 1945 under the Town and Country Planning Ordinance (CAP 84). The duties of the Town and Country Planning Department are mainly: Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. • • • • • • • to formulate and review land use standards for all settlements; to revise settlement legislation; to guide the preparation of settlement structure plans and the management of urban growth; to guide and assist District Assemblies (DA) to establish their own planning departments; to organize training needs of national, regional and district town and country planning departments; to monitor planning related programmes and projects nationwide; and to analyze and review national policy. However, for a long time and under different political systems, the country followed an extended process of decentralization. In 1988 and 1989 the then military government of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) launched a decentralization program which was meant to give power to the people and bring democracy to the doorstep of the people, which was the political philosophy of the government at the time (Ayee, 2013, p. 624). With the Constitution of 1992, upon the return of the country to democratic Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 83 Ministry and Sector Agencies .. ~ ~ ,. ...... National Development Planning Commission ""''III (National Co-ordination body) ~ ~ Regional Coordinating Council ,, (Regional Planning Co-ordinating Unit) District Assemblies (District Planning Co-ordinating Unit) ,, ... .... ...... I ~ ~ ~ ~ Urban/Town/Area and Zonal Council ,,. Legend -+ ~ ~ • Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Unit Committees FIGURE 5.1 Development Plans Planning Guidelines Structure of the planning system in Ghana (Source: authors, based on Inkoom 2008, p. 68) rule, the aim was to first ensure development decision-making at both national and local levels by restructuring the administrative and the political machinery and, secondly, the attainment of functional efficiency and environmental harmony through the reorganization of the system of spatial development and hence the creation of two new institutions: The Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD), dealing with programs and activities of decentralization coordinating national policies for local governments, and the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC), which is responsible for consistency and execution of development policies. The NDPC also guides and assists the 216 Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 84 Wolfgang Scholz et al. Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDA) in the preparation of district development plans, being at the same time the legal institution responsible for the approval of these plans. Furthermore, it cross-checks the district development plans to go in line with the national development plan. The new decentralized planning and decision-making system had three main objectives: • • • to create an institutional framework for public and community participation in national development to ensure optimal resource mobilization, allocation and utilization for development; to provide opportunities for greater participation of local people in development planning and efficient management of local resources; and to establish effective channels of communication between the national government and local communities with increased administrative effectiveness at both levels (Inkoom, 2008, p. 69). TABLE 5.5 Overview of the different planning authorities Level Population Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. 250,000 and above Metropolitan Assemblies (Accra, Kumasi, Shama Ahanta East, Tamale, Tema and Cape Coast) Municipal Assemblies 95,000 and above (56) District Assemblies 75,000 and above Zonal Councils 3,000 and above Urban Councils 15,000 and above Town Councils 5,000–15,000 Area Councils Less than 5,000 Unit Committee 500–1,500 Duties and plans Metropolitan Assembly as planning authority. Development Plan/Structure Plans including Planning Schemes of Local Plans Municipal Assemblies as planning authority. Development Plan/Structure Plans, Local Plans District Assemblies as planning authority. Development Plan/ Structure Plans, Local Plans Parts of the Municipal Assemblies based on the Electoral Commission demarcations. Sub District Local Action Plan Part of District Assemblies. Output: Sub District Local Action Plan Part of Metropolitan and District Assemblies for local participation. Sub District Local Action Plan Grouped settlements which have populations of less than 5,000. Sub District Local Action Plan Bodies for direct participation of the people at lowest level. Implementation and Monitoring of self-help projects. Community and Local Action Plan (Source: based on Inkoom (2008), updated by the authors) Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 85 Between the national and district levels, ten Regional Co-ordinating Councils (RCC) were established. They are responsible for coordinating, monitoring and evaluating of decisions of the MMDAs as well as harmonizing their plans. Those without planning departments are supported by the regional offices of the Town and Country Planning Department. As a result of the 1992 Constitution, Ghana has enacted the following legal framework for planning: • • • • The The The The Civil Service Law 1993 (PNDCL 327); Local Government Act 1993 (Act 462); National Development Planning Commission Act 1994 (Act 479); National Development Planning (Systems) Act 1994 (Act 480). The main idea is that planning should not only deal with land use planning and urban design aspects, but contribute to the economic, social and environmental development on local and national levels. With the National Development Planning (Systems) Act of 1994, the top-down planning approach with one central planning unit for the entire country has been replaced by a more decentralized approach. This Act, together with Local Government Act, designates the local authorities as the planning authorities (see Table 5.5). Community participation is seen as integral part of the process. The new planning system in practice The process of decentralization will be analyzed along the following topics: institutional and organizational set-up; capacity; participation; and politics of the creation of districts. As Ayee and Dickovick (2010, p. 31) argue, “Ghana has several achievements to its credit in the area of decentralization but they are partial and incomplete”. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Capacity Simply, the Town and Country Planning Department lacks capacity to support the local units. In 2005, 54 of the total of 138 districts (39%) still had no town and country planning establishment, and 87 had weak or little planning capacity due to lack of planning officers (Inkoom, 2008, p. 72). Therefore, knowledge and skills available in the districts to facilitate the planning process are limited. Planning requires some basic skills as identification of development challenges, analysis, priority setting and documentation. These skills are limited at the DA level and lacking at both the Area Council and Unit Committee levels (Bandie, 2007, p. 9). The author also states that they are presently ineffective in the performance of their mandated functions, including community mobilization for planning decision-making and advocacy. In some communities, the members of the local Unit committees do not even meet to plan community activities and have never taken responsibility for organizing community-wide consultative meetings Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 86 Wolfgang Scholz et al. (Bandie, 2007, p. 9). Furthermore, there are many parallel institutions that do not coordinate their activities; in addition they have inadequate personnel, old and archaic laws, old and archaic planning standards and guidelines, inadequate logistics and inappropriate planning methods. Institutional and organizational set-up In theory, the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) sets the general planning framework for all other institutions to operate. There is, however, an overlap with other institutions, e.g. the Lands Commission (LC) and the Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD). All are, among many others, involved in spatial planning. Inkoom (2008) describes the dilemma as follows: Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. “As a result, planning conflicts occur through inadequate co-ordination and co-operation among land development agencies. For instance, during the preparation of the land management component of the National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) it was noted that there are as many as 22 institutions concerned with land management. This is compounded by a weak land administration system, some inadequate and out-dated legislation and contradictory policies and policy actors among various public land agencies. This can make planning a rather difficult task with potential to create environmental problems.” Furthermore, the performance of the TCPD is limited because it has been placed at various times under 15 or more different ministries. These frequent changes have a negative impact on its performance. The idea of decentralization and locally based decision-making is constrained by the fact that many Assembly members, who are also members of the Unit Committees and Area Councils, are not in regular contact with their constituent communities. Most of them actually reside outside their electoral areas. This limits their influence on local level development (Bandie, 2007, p. 9). DAs have to follow the procedures, guidelines and goals of the Ministries of the central government. The decentralized units of the DAs are still tied to the apron strings of their mother departments at the national level because their activities are financed by them. There is also little control over staff at the district level as recruitments are done at the national level and posted to the Districts. This leads to the problem that people’s real needs and preferences on the ground might differ from national programs and projects: “For example, in the Sissala district a study found out that whilst the people’s three most preferred projects were identified as water, dam construction, and education, the Sissala District Assembly had over the period under review, focused on education, local government as its priority development sectors.” (Bandie, 2007, p. 10) Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 87 Furthermore, assembly members are also members of political parties and have to follow the agenda of the party leaders (Bandie, 2007, p. 15). There is also an unclear role of civil society organizations and traditional leaders in the decision-making process opening the door for decisions based on individual influence and political power. Another crucial factor related to limited capacities on the lower level is described by Inkoom: “With the advent of the District Assemblies Common Fund, the districts were charged with preparing 5-year development plans. The problem has been that in most cases these plans were prepared by consultants and/or few officers of the DA with the result that plans suffer implementation problems because of ignorance of content by stakeholders, apathy and a lack of commitment among others.” (2013, p. 73) The majority of the Zonal/Urban/Town and Area Councils are without offices and secretaries. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Participation Traditionally, participation is conducted through public forums or by representation. Discussions at these meetings are open to all, but in practice a few vocal individuals dominate the discussions. In most cases women and the marginalized, though they may be present, may not make any contribution or challenge any decision (Inkoom, 2008, p. 73). The possibility to participate goes beyond gender and domination factor and can be constrained simply by accessibility. Accessibility of a community to other communities and the district center influences information flow and the potential for the participation of the community. Communities with good transportation or a closer location to the offices are in a better position to receive information and to participate than those in more remote areas. This is especially related to the Northern Region. Despite transportation also large size of some units also limits interactions among their members. Usually Unit Committees comprise of five to ten communities. In the Northern Region it can go beyond 30 communities (see also Bandie, 2007, p.10). Accountability A major challenge in the decentralization process is accountability. Decentralization only works if officers and political leaders are accountable to their local residents. However, 30% of the officers in the district including the District Chief Executive are appointed by and accountable to the central government. In many cases the allegiance is to the central government directives without any reflection on local needs and priorities. The weak local structures and the indifferent roles of civil Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 88 Wolfgang Scholz et al. society organizations in local governance support the potential abuse of power (Bandie, 2007, p. 14). Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Politics in district creation The number of districts doubled (without the sufficient capacities and funds) from 1988 with 65 to 2007 with 138 and increased further to 170 in 2008 and to 212 in 2012. It seems to reflect a success in the decentralization process; however, it needs a critical view. There are two fundamental approaches towards decentralization of governmental power: fragmentation and consolidation (cf. Marshall and Douglas, 1997; Box and Musso, 2004; Fox and Gurley, 2006). Consolidation is reflected in a preference for strong, centralized administration with few governmental levels and units. The idea is that it will lead to economies and efficiencies in the provision of local services. It would also focus political responsibility and assure a more integrated governmental response to area-wide problems. Consolidation emphasizes the need to improve administrative efficiency, reduce the regional impacts of decisions made by multiple units of government, and address inequities in service provision caused by fragmentation of tax bases and administrative authority. Supporters of the consolidation approach stress that for regional planning, addressing changes and challenges in social and economic developments such as rapid population growth, economic decline, environmental concerns, hard services infrastructure needs or the impact of technological change, the consolidation approach is more comprehensive and can better support an integrated regional land use planning (Ayee, 2013, pp. 625–627). Fragmentation highlights the value of achieving greater allocative efficiency and responsiveness to resident preferences through the location choices freely made by individuals (Box and Musso, 2004). The economic theory argues that individuals benefit from separating into smaller, more homogeneous communities that are better able to match services to local preferences: “The fragmented system, it is argued, makes for more efficient and effective services, and better governance” (Ayee, 2013, p. 627). Obviously, the creation of districts in Ghana follows rather the fragmentation perspective. This, however, does not consider the rationale for the creation of districts. A key issue is the economic viability of the districts. The majority are not self-reliance and depend highly on subsidies and funds from the central government due to a weak own tax base which in turn questions first their creation and secondly their independence in decision-making. “Functional effectiveness – that is, large units – of governments are necessary for the efficient and effective provision of public services has been sacrificed for democratic and political expediency; that is, small units are more conducive to grass roots democracy, a sense of belonging, a high rate of individual participation, and close contact between political elites, leaders, and ordinary citizens. … The central government has in some cases used Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 89 district capitals as a means of either rewarding the communities for their support during elections or shoring up support for the future.” (Ayee, 2013, pp. 631 and 637) The time of the creation of new districts close to elections is an important factor to consider. Political considerations are overshadowing the aim to create viable and functioning districts and district capitals. Their function as focal points for socio-economic development in the district with better infrastructural facilities are used as a political tool to support some areas while others can be victimized for political reasons. Conclusion The case of decentralization in Ghana is more than a success story of democratization of political decisions and participation. It can be also seen as a political tool to support particular areas or groups. The districts themselves are not economically and politically independent entities but rather local structures of the central government which are highly dependent on government funds. In many cases they are too large to guarantee participation of the local residents and at the same time too small to run efficiently and independently. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Conclusion and Way Forward Despite the differences between the case study countries – Tanzania, South Africa and Ghana – there are some lessons to learn and conclusions to draw. All countries face problems with the application of outdated planning laws which are based on colonial rules and reflect a totally different understanding of the size, function and role of the cities. They were designed for well-organized, smaller cities with limited urban growth and not for rapid urbanization. The current high degree of informality in African cities can be therefore understood not as a phenomenon of the African city per se but rather as a result of inappropriate and not applicable planning laws. Berrisford (2013, p. 1) summarizes the current situation: “As competition for land intensifies in Africa’s rapidly growing towns and cities, planning laws assume a fundamental importance. They determine how urban growth is managed and directed. In most countries outdated, inappropriate and unintegrated laws are exacerbating urban dysfunction.” Furthermore, the countries face serious problems between the underlying understanding of a state and its governmental power and procedures on the one hand (adopted from colonial times) and traditional leaders and party leaders on the other hand which do not necessarily accept legal frameworks and administrative procedures and decision-making processes. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 90 Wolfgang Scholz et al. We argue that the development of towns and cities are hardly ever influenced by statutory or formal planning policy, because of the strength of customary landholders and leaders and the weakness in the current institutional arrangement for planning delivery. The reform of planning law is a necessary step for better management of urbanization in Africa. However, current approaches tend to focus on the establishment of a parallel system to the current legal framework (Sustainable Cities Programmes from UN Habitat, various donor-driven projects on settlement upgrading, urban management projects or, for example, the LEFTEA in South Africa) instead of starting from zero to create a new and appropriate planning system which reflects African urban realities, capacities and traditions. Berrisford (2013, p.1) therefore stresses in the publication Counterpoint: The promotion of “one-size-fits-all” and “model” planning laws from outside the continent has not served Africa well. Invariably it has created further legal uncertainty and a series of unanticipated, often pernicious consequences. This Counterpoint argues that more progressive, realistic urban planning in Africa will require a radically different approach to planning law reform. This is essential for sustainable and equitable urban development in Africa. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Obviously, the authors are not in the position to design new planning legislation, but from the case studies, we can draw some conclusions and identify key entry points and requirements for a new planning framework. Starting from the observation by Watson and Agbola (2013, p. 3) that: “The plans assumed an orderly and law-abiding population that was willing to comply with zoning and building laws and formally employed families. For most inhabitants of African cities, outdated planning laws are an irrelevance – until deployed against them by the vindictive or opportunistic. Most urban development in Sub-Saharan Africa is occurring in a completely non-planned and non-transparent manner – despite the existence of master plans” Reform of planning (and associated urban development laws) should be guided by the legal principle of intra vires (within the legal power) which means you are permitted to do anything except what is specified as not allowed. The prevailing principle of ultra vires (beyond the legal powers) means you can only do what is specifically permitted. A new system of planning law to manage land use in existing and new urban areas (planned and unplanned) should be tailor-made for each country so as to be understood, relevant and enforceable given the particular traditions, decision-making processes and capacities of key role players. Emphasis should be on identification of the absolute minimum of what is NOT permitted in terms of uses and changes of use. Areas of a city which have more capacity can Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 91 introduce more nuanced land use management measures on top of the minimum. The legislation/regulations should be formulated taking into account activities and decisions by all stakeholders (e.g. more than planning permission, but to include licensing, building regulations, and so on) and be able to be easily understood by residents, businesses, local leaders, and administrators. The approval system needs to be designed on a one-stop basis to ensure prompt, transparent decision-making. Another issue to address is the parallel system of governmental legal procedures, including the planning legislation and traditional local leaders (e.g. in Ghana) or leaders of the ruling party or village committees (e.g. in Tanzania) who are also dealing with planning-related topics including land management. This parallel system can benefit from loopholes in and failure of the legal planning system and receives, in many cases, a higher degree of trust from local residents due to tradition. It can also be seen as still a problem of the state following colonial legislation and procedures which are not recognized by the majority of the residents; this again displays the weakness of the government in applying colonial laws but also highlights the attitude of local residents who would rather follow a wellknown person or authority on the ground than a written law. A new planning system should therefore reflect these political power relations and make use of traditional local leaders by cooperating them into planning procedures. There is the need to involve all stakeholders including civil society and non-governmental organizations in the development process. The examples of Tanzania and Ghana clearly reflect the parallel system. The idea of decentralization in Ghana could have been an appropriate approach; however, it failed due to the strong influence of the central government and its politics and parallel structures between traditional local leaders and understaffed district offices. Decentralization has come with decentralized development planning. Political authorities must have the will and commitment, national bureaucrats must accept to cede power and control, and sub-national governments must also develop capacity to govern. While the topic above goes far beyond planning-related issues and deals more with the situation of the post-colonial state itself, let’s have a closer look at the need to revise the planning legislation. Watson and Agbola (2013, p. 2) stated that: There is little enthusiasm for reform from within. Yet planning is the single most important tool that governments have at their disposal for managing rapid urban population growth and expansion. If inclusive and sustainable planning replaced outdated, controlling and punitive approaches it would underpin more equitable and economically productive urban development in Africa. Crucially, change depends on planners who are innovative problem solvers and willing to collaborate with all parties involved in the development process, including local communities. In order to achieve these goals, there is a need to revise planning education as well. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 92 Wolfgang Scholz et al. In many countries, the course design and the underlying urban models including text books have been imported from Europe in the 1970s and 1980s. “The education of these future planners requires thorough reappraisal of existing teaching methods, the introduction of new ones, and remodelled curricula” (Watson and Agbola, 2013, p. 2). One positive development is the initiative of the Association of African Planning Schools (AAPS) to revise the current planning education at African planning schools focusing on: informality; access to land; climate change; collaboration between planners; communities, civil society as well as other interested parties; and addressing the mismatch between spatial planning and infrastructure planning (Watson and Agbola, 2013, p. 6). However, the authors from AAPS are aware that: On graduation, they (planning practitioners) might be expected to implement outdated planning legislation, or design golf courses or gated communities for the wealthy. But unless planning students are exposed to the prevailing conditions and trends in African cities, and encouraged to consult and interact with local communities to assess how planning might best address these, they will merely advance the marginalisation of the planning profession – and of the poor – in Sub-Saharan Africa. (Watson and Agbola, 2013, p. 6) Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. References Ayee, J. (2013). The Political Economy of the Creation of Districts in Ghana, Journal of Asian and African Studies, 48. Ayee, J. R. A. and Dickovick, J. T. (2010). Comparative Assessment of Decentralization in Africa: Ghana Desk Study, Report prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, DFD-I-00-04-00227-00. Bandie, B. (2007). Without title, Paper Presentation at the Best Practices Conference on Decentralisation in Ghana, Accra: Institute of Local Government Studies, Madina. [online] Available at: www.discap.org/Publications/Paper_presented_by_Bandie_ NDPC_%20BP_Conference_May2007.pdf [Accessed 22 August 2014]. Baumann, T. (2003). Housing Policy and Poverty in South Africa, in Khan, F. and Thring, P., Housing Policy and Practice in Post-Apartheid South Africa, Johannesburg: Heinemann. Behrens, R. B. and Watson, V. (1996). Making Urban Places. Principles and Guidelines for Layout Planning, Cape Town: Urban Problems Research Unit, University of Cape Town. Berrisford, S. (2013). How to make planning law work for Africa, London: Africa Research Institute. Box, R. C. and Musso, J. A. (2004). Experiments with local federalism: Secession and the neighborhood council movement in Los Angeles, The American Review of Public Administration, 34 (3): 259–276. Burra, M. and Kyessi, A. (2008). Tanzania, in International Manual Of Planning Practice, The Hague: ISoCaRP. Calderwood, D.M. (1956). Town Planning: with particular reference to housing layout, Pretoria: National Building Research Institute. Cato Manor Development Association, Review 1994–2002, (CMDA) Durban, 2003. Dewar, D. and Kaplan, M. (2004) Disjuncture between project design and realities on the ground, in Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. Colonial Planning Concept and Post-colonial Realities 93 Robinson, P., McCarthy, J. and Forster, C. (2004) Urban Reconstruction in the Developing World. Learning through an international best practice, Sandown: Heinemann: 132–144. Floyd. T. B. (1951). Guidelines for Township Layout, Pretoria: National Building Research Institute. Fox, W. F. and Gurley, T. (2006). Will consolidation improve sub-national governments? World Bank Working Paper, 3913: 1–45. Godehart, S. (2006). The transformation of Townships in South Africa, The case of kwaMashu, Durban, Spring Research Series (49) University of Dortmund. Greater Cato Manor Development Forum (GCMDF) (1992). A policy framework for Greater Cato Manor, Durban: Report to GCMDF. Holborn, L. (2013). Fast Facts No. 9 September, Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations. Inkoom, D. (2008). Ghana, in: International Manual of Planning Practice, The Hague: ISoCaRP. Khan, F. (2003).Housing Poverty and the Macroeconomics, in Khan F and Thring P, Housing Policy and Practice in Post-Apartheid South Africa, Johannesburg: Heinemann. Kombe, W. (2011). The Cost of Urbanisation in Tanzania. Paper presented at the expert workshop on 10th August 2011, Dar es Salaam. Kombe, W. J. and Kreibich. V. (2007). The Governance of Informal Urbanisation in Tanzania, Dar es Salaam: Mkuki ya Nyoto Publishers. Lupala, J. (2013).Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Tanzanian Association of Planners, Dar es Salaam. Marshall, J. A. and Douglas, D. J. A. (1997). The Viability of Canadian Municipalities: Concepts and Measurements. Toronto: UCURR Press. Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, United Republic of Tanzania (2011). Plot size standards, unpublished internal draft. National Building Research Institute (NBRI) (1983). Guidelines for the Provision of Engineering Services in Residential Townships. Pretoria: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. Njoh, Ambe J. (1999). Urban planning, housing and spatial structures in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nature, impact and development implications of exogenous forces, Aldershot: Ashgate. Payne, G. (2001). The impacts of regulation on the livelihood of the poor. Paper prepared for the ITDG research project: Regulatory guidelines for urban upgrading Project Preparation Trust (PPT) (2011). Information Document: eThekwini’s Basic Interim Services Programme, Durban. Republic of South Africa (1949). Natal Town Planning Ordinance No. 27. Republic of South Africa (1991). Less Formal Township Establishment Act. Republic of South Africa (1997). Housing Act 107. Republic of South Africa (2000). Development Facilitation Act. Republic of South Africa (2000). National Housing Code Republic of South Africa (2002).The Planning Profession Act. Republic of South Africa (2008). Planning and Development Act 6. Republic of South Africa (2012). Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act. Ryser, J. and Franchini, T. (eds) (2008). International Manual of Planning Practice, ISoCaRP, The Hague. Ryser, J. and Ng, W. (eds.) (2005). Making spaces for the creative economy, REVIEW 01, The Hague: ISoCaRP. The Planning Initiative Team (TPI) (2008a). Guidelines for Planning Facilities in KwaZuluNatal, Standards series volume 84, KwaZulu-Natal, Provincial Planning and Development Commission. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07. 94 Wolfgang Scholz et al. Copyright © 2015. Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. The Planning Initiative Team (TPI) (2008b). Assessment of Planning Standards in KwaZuluNatal, Standard series volume 84, KwaZulu-Natal, Provincial Planning and Development Commission. Watson, V. and Agbola, B. (2013). Who will plan African Cities? London: Africa Research Institute. Silva, C. N. (2015). Urban planning in sub-saharan africa : Colonial and post-colonial planning cultures. Taylor & Francis Group. Created from corvinus on 2023-11-20 07:48:07.