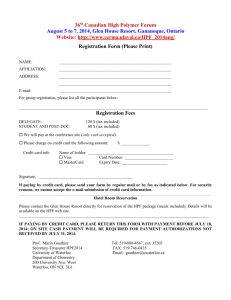

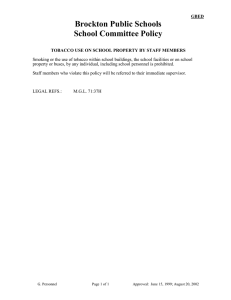

Received: 15 February 2023 Accepted: 13 July 2023 DOI: 10.1111/add.16332 RESEARCH REPORT US tobacco companies selectively disseminated hyper-palatable foods into the US food system: Empirical evidence and current implications Tera L. Fazzino 1,2 | Daiil Jun 1,2 1 Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA 2 Cofrin Logan Center for Addiction Research and Treatment, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA | Lynn Chollet-Hinton 3 | Kayla Bjorlie 1,2 Abstract Background and aims: US tobacco companies owned leading US food companies from 1980 to 2001. We measured whether hyper-palatable foods (HPF) were disproportionately developed in tobacco-owned food companies, resulting in substantial tobacco- 3 Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, USA Correspondence Tera Fazzino, Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, 1415 Jayhawk Boulevard, 4th Floor, Lawrence, KS 66046, USA. Email: tfazzino@ku.edu Funding information There was no funding for this study. related influence on the US food system. Design: The study involved a review of primary industry documents to identify food brands that were tobacco company-owned. Data sets from the US Department of Agriculture were integrated to facilitate longitudinal analyses estimating the degree to which foods were formulated to be hyper-palatable, based on tobacco ownership. Setting and cases: United States Department of Agriculture data sets were used to identify HPF foods that were (n = 105) and were not (n = 587) owned by US tobacco companies from 1988 to 2001. Measurements: A standardized definition from Fazzino et al. (2019) was used to identify HPF. HPF items were identified overall and by HPF group: fat and sodium HPF, fat and sugar HPF and carbohydrates and sodium HPF. Findings: Tobacco-owned foods were 29% more likely to be classified as fat and sodium HPF and 80% more likely to be classified as carbohydrate and sodium HPF than foods that were not tobacco-owned between 1988 and 2001 (P-values = 0.005–0.009). The availability of fat and sodium HPF (> 57%) and carbohydrate and sodium HPF (> 17%) was high in 2018 regardless of prior tobacco-ownership status, suggesting widespread saturation into the food system. Conclusions: Tobacco companies appear to have selectively disseminated hyperpalatable foods into the US food system between 1988 and 2001. KEYWORDS Addictive food, fat, food environment, formulation, policy regulation, sodium I N T R O D U CT I O N which may come at great expense to public health [3]. Federal regulation can serve as a powerful counterweight to protect population Product formulation is an important public health issue. Food health. and drug products sold to consumers may contain chemicals During the US tobacco epidemic of the 1950s, tobacco compa- and ingredients that may negatively impact consumer health [1, 2]. nies formulated cigarette products to maximize their addictiveness at Furthermore, products such as tobacco and highly palatable foods the expense of public health, and incurred federal regulation as a may be designed to maximize public consumption and industry profits, result [4, 5]. Tobacco companies maximized the addictiveness of their Addiction. 2023;1–10. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/add © 2023 Society for the Study of Addiction. 1 FAZZINO ET AL. cigarettes by using a specific nicotine content delivery threshold out and consume HPF [24, 25]. These consequences are similar to (≥ 0.7 mg) and manipulating the form of nicotine to maximize its deliv- other substances of abuse, including nicotine [19]. Our previous work ery upon inhalation [4, 6]. They also added ingredients to increase the revealed that the prevalence of HPF, particularly HPF with elevated palatability and acceptability of cigarettes, such as menthol and fat and sodium, increased substantially in the US food system sugar [7]. Thus, tobacco companies used product formulation as a key during the past 30 years, with the steepest increase during 1988– tool in maximizing the addictiveness of their cigarettes. In addition to 2001 [26], the primary period of tobacco company ownership in the product formulation, tobacco companies also used aggressive and food system. targeted marketing strategies to promote wide use of their products The purpose of the study was to determine the degree to which [4, 7]. Tobacco companies advertised heavily to children to expressly tobacco companies formulated their food products to be hyper- preserve the viability of the tobacco market for future generations, palatable, relative to food companies that were not tobacco-owned. and promoted menthol cigarettes to minoritized racial and ethnic We hypothesized that HPF may be an addictive agent disproportion- communities [4, 7]. Following revelations of these practices in the ately developed in tobacco-owned food products, resulting in sub- 1990s, the US federal government responded by regulating the avail- stantial tobacco-related influence on the US food system. ability and marketing of tobacco products [4]. In part as a response to tobacco industry regulation, the largest US tobacco companies, Phillip Morris (PM) and RJ Reynolds METHODS (RJR), diversified their investments by buying into the US food industry [8, 9]. In the early 1980s PM bought major US food compa- The study was conducted in 2022 at the University of Kansas. The nies including Kraft and General Foods. By 1989, PM’s combined study involved a two-part process in which (1) tobacco industry docu- Kraft–General Foods was the largest food company in the world ments were searched to identify a comprehensive list of food brands [8, 10]. RJR had a slower trajectory of entry to the food industry that were owned by PM and RJR; and (2) food system data sets from and bought into the US beverage market in the 1960s, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) were used to acquiring a limited number of specialty convenience food brands identify foods that were and were not tobacco-owned from 1988 (e.g. puddings and maple syrup brands) throughout the 1970s to 2018. Databases were integrated to facilitate longitudinal analyses [11, 12]. However, in 1985 RJR purchased major cookie and cracker estimating the likelihood that food products were formulated to be brand Nabisco, which doubled company food profits in a single year hyper-palatable based on tobacco-ownership status. and solidified their status as a leader in the US food industry [13]. Years selected for the study corresponded to tobacco company Collectively, PM- and RJR-owned companies dominated the US food leadership in the US food system and the availability of data sets from system between the late 1980s to the early 2000s [14–17]; thus, the USDA. The years 1988 and 2001 were selected to represent a companies that specialized in creating addictive tobacco products period in time during which US tobacco companies dominated the US led the development of the US food system for > 20 years (see food market [14–17]. The anchor year of 1988 was selected based on Fazzino [18] for a detailed review of industry activities). In this data availability from the USDA, and aligned with the 1989 merger of regard, evidence has revealed that RJR and PM directly applied their Kraft–General Foods by PM, which facilitated PM’s leadership in the tobacco product formulation strategies to their food company prac- food system [8]. The year 2001 represented the final period that both tices [8, 9]. Tobacco-owned food subsidiaries learned product for- companies led industry sales [16]. The date of 2018 represented the mulation strategies from company tobacco scientists, which included most recently available data set from the USDA on branded foods in adding a variety of appealing colors to their sugar-sweetened bever- the food system at the time of the study. ages, and adding sugar and caffeine to maximize consumption [8]. However, no further research has examined the ways in which the application of tobacco product formulation techniques may have Classification of tobacco-owned food brands influenced the US food system. Prior studies have described how certain foods may have addic- To identify food brands and products that were owned by PM and tive qualities similar to those of tobacco products and other sub- RJR, internal industry documents were reviewed through the Univer- stances of abuse [18, 19]. Such foods, termed hyper-palatable foods sity of California San Francisco’s Industry Documents Library (IDL), a (HPF), may be an addictive agent that tobacco companies developed repository of primary source industry documents that is freely avail- in their food products. HPF are designed with combinations of able to researchers and the general public [27]. A systematic, iterative palatability-inducing ingredients (fat, sugar, sodium and/or carbohy- search process was conducted to identify documents that reported all drates) that create an artificially rewarding eating experience [20]. brands and food products owned by PM and RJR to facilitate their These combinations of nutrients do not occur in nature; as a result, subsequent identification in the USDA food data sets (detailed below). these foods can excessively activate brain reward neurocircuitry The search process is summarized herein and reported in detail in the [21, 22] and facilitate excess caloric intake [23]. Repeated Supporting information section. Searches were conducted in the Truth consumption of HPF over time may result in dysregulation of food Tobacco Industry Documents Collection and the Food Industry Docu- reinforcement processes, leaving individuals highly motivated to seek ments Collection. Initial searches were conducted broadly to identify 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 2 the types of industry documents that most comprehensively reported comparison of the HPF status of foods that were tobacco-owned in all tobacco-owned brands and food products (see Supporting informa- 1988, relative to the same food items that were not tobacco-owned tion section for more details). A second refined search focused on col- (e.g. saltine cracker). Secondly, a longitudinal file was created with lecting reports, tobacco-owned food items that were present in 1988 and 2001. This shareholder reports), which typically contained comprehensive food summary-style company reports (e.g. annual facilitated an analysis of the HPF status of tobacco-owned food items brand listings. A third search was conducted to identify any remaining between 1988 and 2001, relative to the same types of food that were summary-style tobacco company reports available in the IDL not cap- not tobacco-owned. Finally, the HPF status of food items with versus tured in the first two search rounds. Twenty-five documents were col- without a history of tobacco ownership as of 2018 were compared lected and reviewed in detail, and a total of 373 tobacco-owned cross-sectionally to test whether previous tobacco ownership may be brands were identified (Supporting information, Table S1). In addition, associated with the HPF items available in the current food environ- most reports also provided performance comparisons with competitor ment. Prevalence rates of HPF throughout branded foods previously products/companies, which were used to identify brands that were tobacco-owned and foods not previously tobacco-owned were also not tobacco-owned at the same period. quantified. Data sources on food hyper-palatability Measure of hyper-palatability Following the search of industry documents, tobacco-owned foods Foods were identified as HPF using the standardized definition from were identified in publicly available data sets from the USDA, which Fazzino et al. [20]. The definition was informed by evidence indicating are considered representative of the US food system. Figure 1 depicts a combination of palatability-inducing ingredients (fat, sugar, carbohy- the data sets used in the study. Data sets were compiled to represent drates and/or sodium) at specific thresholds may induce hyper- three periods of time: 1988, 2001 and 2018. The NHANES-III palatability. The definition specifies quantitative combinations of 24-hour dietary recall assessment (conducted from 1988 to 1994) nutrients at thresholds that may yield hyper-palatability: (1) fat and was used to identify tobacco-owned foods as of 1988 [28]. The USDA sodium (FSOD), (2) fat and simple sugars (FS) and (3) carbohydrate Standard Reference Databases for 1997, 1998 and 1999 and the and sodium (CSDO) (detailed in the Data analysis section, below) [20]. 2001 Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies were used to The HPF definition has excellent convergent validity for identifying identify tobacco-owned food items between 1997 and 2001 [29–32]. foods hypothesized to be hyper-palatable [20], strong discriminant The 2018 Branded Foods Database was used to characterize previ- validity for foods hypothesized to not be hyper-palatable (e.g. raw ously tobacco-owned foods for 2018 [33]. A parallel process was con- fruit) [20] and is distinct from constructs such as energy density and ducted to identify food items not tobacco-owned for respective time- ultra-processed foods [20, 34]. Furthermore, evidence indicates HPF periods, informed by competitor products identified in tobacco indus- may be the target of clinically defined binge-eating episodes [35] and try documents. that highly processed HPF may be the target of food addiction [36], Several data files were compiled for analysis (see Figure 1). First, a matched-cases file was created to facilitate a cross-sectional FIGURE 1 Data-sets and corresponding analyses. supporting the premise that HPF may have strong addictive properties. 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 3 TOBACCO COMPANIES AND HPF FAZZINO ET AL. Identification of hyper-palatable foods previously tobacco-owned in 2018. Modified Poisson regression models with robust standard errors (fixed effects only) were used to The HPF definition was applied to all food data in accordance with characterize the magnitude of the differences via prevalence ratios the published measure (detailed in the Supporting information (PR). The study analyses were not pre-registered. section) [20]. The percentage of kilocalories (kcal) from fat, sugar and carbohydrates (following subtraction of fiber and sugar) and percentage of sodium by weight in grams were calculated. Items that met RE SU LT S criteria for at least one of the following were classified as HPF: (1) FSOD (> 25% kcal from fat, ≥ 0.30% sodium), (2) FS (> 20% kcal fat, > 20% kcal sugar) and (3) CSOD) (> 40% kcal carbohydrates, Tobacco company food brand ownership and representation in the study data-sets ≥ 0.20% sodium) [20]. A total of 105 tobacco-owned food items and 587 nontobacco-owned food items were present in both data sets used in the Data analysis longitudinal analyses (1988 and 2001), yielding a total sample size of 692. The 105 foods identified as tobacco-owned were representative Figure 1 depicts analyses conducted with corresponding data sets. of the brands and food items sold by PM and RJR, owners of the larg- First, a McNemar’s χ2 test was conducted with the matched pairs of est food companies in the US market [17, 37]. RJR’s largest food foods to determine whether there were differences in the HPF status brands were Nabisco and Planters Lifesavers [17] and the following of foods that were tobacco-owned relative to matched food items products led sales as of 1989: cookies and crackers from sub-brands that were not tobacco-owned in 1988. Three additional McNemar’s Oreo, Grams (Nabisco/Teddy), Ritz and Premium [17], all of which χ2 tests were conducted to determine whether there were differences were represented in the data set. PM-owned Kraft–General Foods in the status of foods that were tobacco-owned for each HPF group comprised the following categories: cereals/baked goods, grocery (FSOD, FS and CSOD) [20] relative to the same foods that were not products (e.g. Miracle Whip, side dishes), processed meats (e.g. Oscar tobacco-owned. Mayer hot dogs/sausages) and frozen/convenience meals [16, 37]. To examine whether tobacco company ownership of food items These food categories comprised 75% of PM’s total food sales was associated with change in the likelihood that foods were classified between 1989 and 1993 [37], and all types of foods were represented as HPF in 2001 relative to 1988, a modified Poisson regression model in the data set. RJR and PM largely retained these principal brand lines with mixed effects and robust standard errors using sandwich variance throughout their ownership in the food system [to 2001 (RJR) or estimation was used to estimate risk ratios (RRs) accounting for 2007 (PM)] [15, 16]. Thus, the identified tobacco-owned foods were repeated measures, with a random intercept for food item to account highly representative of the overall product lines and highest volume for correlated HPF status among repeated food items and fixed sales products from RJR and PM in 1988–2001. effects for database year and tobacco-ownership status. Three parallel models were also constructed with each HPF group (FSOD, FS and CSOD) as dichotomous outcomes to determine if tobacco company ownership was differentially associated with type of HPF. In addition, Matched-pairs analysis of food item hyper-palatability and tobacco ownership in 1988 an interaction effect of year by tobacco ownership was added and tested as a fixed effect for all primary models to determine if An examination of 145 matched pairs of food items indicated that in change in HPF status depended upon tobacco company ownership. 1988, there were no significant differences in the likelihood that Tobacco-owned foods represented the following categories: cook- tobacco-owned food items were hyper-palatable, relative to their ies, crackers, meats and cheeses, frozen foods, salad dressings, cereals matched food items that were not tobacco-owned (HPF: McNemar’s and bakery items. Therefore, foods that were from the same food cate- χ2 = 0.100, P = 0.752; FSOD HPF: McNemar’s χ2 = 0.063, P = 0.803; gories but owned by a non-tobacco food company were included as FS HPF: McNemar’s χ2 = 0.0001, P = 0.999; and CSOD HPF: comparator foods in the primary longitudinal analyses. To examine the McNemar’s χ2 = 0.450, P = 0.502). Findings from this analysis suggest impact of tobacco ownership on HPF availability within the broader US that during the time that tobacco companies purchased and devel- food environment, a second set of modified Poisson regression models oped food companies, they did not selectively acquire food products with robust standard errors for RR estimation included all food items that were hyper-palatable. that were not tobacco-owned from any food category (3371 items), together with the tobacco-owned items, and included HPF, FSOD HPF, FS or CSOD HPF as the outcome in four separate models. Finally, to understand the current status of the food system in the Food item formulation by year and tobacco company ownership: 1988–2001 context of prior tobacco ownership, we calculated the proportion of HPF overall and each group (FSOD, FS and CSOD) among foods that Findings from the repeated-measures Poisson models are reported in were ever tobacco-owned, relative to food items that were not Table 1. Results indicated that tobacco company ownership was 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 4 TABLE 1 Food item hyper-palatability by year and tobacco company ownership. Year β (SE) P-value Risk Ratio (95% CI) HPF overall 1988 (ref ) – – 2001 −0.005 (0.015) 0.746 0.995 (0.966, 1.025) Tobacco-owned 0.010 (0.050) 0.849 1.010 (0.916, 1.113) 1988 (ref) – – 2001 −0.006 (0.024) 0.793 0.994 (0.949, 1.041) Tobacco-owned 0.257 (0.099) 0.009 1.293 (1.065, 1.569) 1988 (ref) – – 2001 −0.066 (0.040) 0.097 0.936 (0.865, 1.012) Tobacco-owned −0.796 (0.220) < 0.001 0.451 (0.293, 0.694) Fat and sodium HPF Fat and sugar HPF Carbohydrate and sodium HPF 1988 (ref) – – 2001 0.075 (0.063) 0.232 1.078 (0.953, 1.218) Tobacco-owned 0.593 (0.213) 0.005 1.810 (1.193, 2.745) Note: Model specified random intercept for food item and fixed-effect for database year. Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HPF = hyper-palatable foods; SE = standard error. significantly associated with the likelihood that food items were contrast to primary model findings, tobacco ownership was not sig- FSOD HPF and CSOD HPF, showing that tobacco ownership was nificantly associated with fat and sugar HPF items (RR = 0.867, consistently associated with food item hyper-palatability for FSOD P = 0.550; Table 2). and CSOD over time (P-values = 0.005–0.009; Table 1). Tobaccoowned foods were 29% more likely to be classified as fat and sodium HPF (RR = 1.293) and 80% more likely to be classified as carbohy- Differences in food item hyper-palatability in 2018 drate and sodium HPF (RR = 1.809) between 1988 and 2001, relative to the same types of foods that were not tobacco-owned (Table 1). Differences in the hyper-palatability of foods that were ever tobacco- Figure 2 displays the predicted probabilities that food items were owned (n= 5031) in 2018 relative to food items that were not previ- FSOD HPF and CSOD HPF for tobacco-owned items and non- ously tobacco-owned (n= 112105) were examined. As of 2018, the tobacco-owned items. There was no significant association between proportions of HPF among foods that were and were not previously tobacco company ownership and the likelihood that food items were tobacco-owned were consistently very high (75.2 versus 76.9%), HPF overall (Table 1). In addition, tobacco company ownership was regardless of ownership status (PR = 0.977; P = 0.165; Table 3). There associated with a lower likelihood that food items were fat and sugar were, however, statistically significant differences in the proportion of HPF (RR = 0.451, P = 0.0003; Table 1), suggesting that tobacco foods that were classified as FSOD HPF, FS HPF or CSOD HPF based companies consistently avoided fat and sugar HPF in their products. on prior tobacco ownership (Table 3). The prevalence of FSOD HPF No significant interaction effects between tobacco ownership and was high overall (60.6 versus 57.9%), and there was a small but year were observed for HPF overall (FSOD HPF, FS HPF or CSOD statistically significant 4% greater prevalence of FSOD HPF among HPF; P-values = 0.088–0.825), suggesting that the likelihood that previously tobacco-owned items (PR = 1.046, P = 0.014; Table 3). food items became HPF across years did not vary according to tobacco ownership (see Supporting information, Table S2 for full model results). DI SCU SSION Similar to the primary findings, models that included all food system data indicated that tobacco company ownership was signifi- Products sold to US consumers, such as tobacco and hyper-palatable cantly associated with an increased likelihood that foods were foods, may be designed to maximize public consumption at great risk FSOD HPF (RR = 1.485, P = 0.0001) and CSOD HPF (RR = 1.725, to public health [3]. In this regard, commonalities between the prac- P = 0.005) over time (Table 2). Furthermore, tobacco company own- tices of US tobacco and food companies have been highlighted for ership was significantly associated with a higher likelihood that food the past 20 years [3, 38, 39]. This paper underscores the fact that items were HPF overall (RR = 1.320, P = 0.0001; Table 2). In these commonalities are the direct result of shared ownership: US 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 5 TOBACCO COMPANIES AND HPF FAZZINO ET AL. FIGURE 2 ownership. Predicted likelihood of food item classification as fat and sodium HPF and carbohydrate and sodium HPF by tobacco company tobacco giants Phillip Morris and RJ Reynolds owned leading US food between 1988 and 2001, a time during which tobacco-owned food companies between the 1980s and early 2000s and dominated the companies led the US food industry [15–18, 37]. The three types of US food system in sales per year [15–18, 37]. Our prior work docu- HPF have distinct formulations (fat and sodium HPF; fat and sugar ments the dramatic rise in HPF prevalence in the US food system dur- HPF; carbohydrates and sodium HPF), and our evidence suggests that ing the past 30 years [26]. Our current study findings indicate that tobacco companies may have selectively targeted the promotion and one reason for this rise may be that tobacco companies were more dissemination of two types of HPF, specifically fat and sodium HPF likely to disseminate foods that were hyper-palatable into the food and carbohydrate and sodium HPF. The tobacco companies’ food system between 1988 and 2001, relative to food companies that product portfolios were heavily represented by meal-based items such were not tobacco-owned. Foods that were tobacco-owned were 29% as meats, cheeses and frozen dinners, which typically meet criteria as more likely to be fat and sodium HPF and 80% more likely to be car- fat and sodium HPF [20, 26]. Thus, the development of fat and bohydrate and sodium HPF during 1988 and 2001 relative to foods sodium HPF align with their food company portfolios. Additionally, that were not tobacco-owned. Finally, analyses of the most recent tobacco companies owned leading cookie and cracker brands data (2018) revealed that the prevalence of HPF overall, and fat and (e.g. Nabisco) [20], which produced foods that may be carbohydrate sodium HPF specifically, was extremely high among branded foods and sodium HPF, which is also consistent with our findings. However, that were previously tobacco-owned, as well as those that were not, using the same rationale, cookie products often align with fat and suggesting widespread saturation of HPF in the US food system. sugar HPF, and thus it is curious that tobacco companies did not Our findings indicate that tobacco companies were consistently selectively disseminate these products into the food system. In fact, involved in the dissemination of HPF into the US food system our evidence indicated that tobacco-owned food companies were less 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 6 TABLE 2 Food item hyper-palatability by year and tobacco company ownership-full food system. β (SE) Year P-value Risk Ratio (95% CI) HPF overall 1988 (ref) – – 2001 0.021 (0.011) 0.049 1.021(1.000, 1.043) Tobacco-owned 0.278 (0.048) <0.001 1.321 (1.203, 1.450) Fat and sodium HPF 1988 (ref) – – 2001 0.003 (0.015) 0.830 1.003 (0.974, 1.034) Tobacco-owned 0.396 (0.091) <0.001 1.486 (1.244, 1.775) Fat and sugar HPF 1988 (ref) – – 2001 0.018 (0.026) 0.489 1.018 (0.967, 1.072) Tobacco-owned −0.142 (0.238) 0.550 0.868 (0.545, 1.382) Carbohydrate and sodium HPF 1988 (ref) — 2001 0.054 (0.029) 0.063 1.056 (0.997, 1.118) Tobacco-owned 0.546 (0.194) 0.005 1.725 (1.180, 2.522) Note: Model specified random intercept for food item and fixed-effect for database year. Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HPF = hyper-palatable foods; SE = standard error. TABLE 3 Differences in food item hyper-palatability in 2018 based on history of tobacco company o ownership. Percentage tobacco-owned (n/N) Percentage not tobacco-owned (n/N) HPF 75.2% (3784/5031) FSOD HPF Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) P-value 76.9% (86284/112105) 0.977 (0.946, 1.009) 0.165 60.6% (3047/5031) 57.9% (64879/112105) 1.046 (1.009, 1.085) 0.014 FS HPF 35.8% (1801/5031) 25.6% (28375/112105) 1.414 (1.348, 1.483) < 0.001 CSOD HPF 17.2% (865/5031) 22.4% (25156/112105) 0.766 (0.715, 0.819) < 0.001 Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; CSOD = carbohydrate and sodium HPF; HPF = hyper-palatable foods; FS = fat and sugar HPF; FSOD = fat and sodium HPF. likely to promote fat and sugar HPF relative to food companies that HPF availability in our current food environment. Foods that were were not tobacco-owned. Considered within the context of the ever tobacco-owned showed slightly higher relative prevalence (4%) broader food system, in the 1990s to the early 2000s there was a of fat and sodium HPF classification in 2018 relative to foods that growing concern regarding sugar contributing to obesity risk [40], and were never tobacco-owned, suggesting that history of tobacco com- US dietary recommendations included reducing/moderating sugar pany ownership may still distinguish foods that are fat and sodium consumption, particularly from sweets and snacks [41]. To induce HPF. However, the prevalence of fat and sodium HPF was high overall hyper-palatability, food companies have limited nutrients to modify (> 57%) and the percentage difference was small (2.7%). Thus, it may (fat, sugar/carbohydrates and sodium) [42]; thus, tobacco companies be that companies that were not tobacco-owned observed the suc- may have avoided promoting HPF with elevated fat and sugar, and cess and market competitiveness of tobacco-owned food companies, instead focused on foods that could be enhanced with sodium, and began producing HPF to remain competitive in the market. Similar thereby remaining under the detection of most nutritional advice and instances in which tobacco companies observed competitor successes public scrutiny. with cigarettes, and subsequently changed product formulations to Our analyses indicate that the proliferation of HPF in prior remain market-competitive, occurred during the tobacco epidemic [4]. decades during tobacco company-ownership may have influenced The same process may explain the small differences observed in the 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 7 TOBACCO COMPANIES AND HPF FAZZINO ET AL. proportion of carbohydrate and sodium HPF that were and were not previously tobacco-owned in 2018. Overall, findings of the current C O N C LU S I O N S A N D P U B L I C H E A LT H IMPLICATIONS study suggest that tobacco company involvement in the US food system may have had long-standing consequences for the availability of This study found that US tobacco companies appear to have selec- HPF, which currently saturate the US food environment [26]. tively disseminated fat and sodium HPF and carbohydrate and sodium Our study found strong evidence indicating that tobacco compa- HPF products into the US food system between 1988 and 2001, and nies were consistently involved with HPF products over time; how- that these products have become highly prevalent in the US food ever, we did not find direct evidence of product reformulation, and environment today. Despite growing scientific evidence regarding the further work is needed to understand and characterize tobacco com- addictive properties of HPF [19], there are no federal regulations pany involvement in this area. In this regard, our matched-pairs analy- addressing HPF accessibility. The state of the food environment for sis determined no observed difference in the proportion of HPF by US consumers bears a striking resemblance to the US environment in tobacco ownership in 1988, suggesting that tobacco companies did the 1950s during the tobacco epidemic, before the US federal gov- not acquire products that were already HPF in 1988. However, our ernment regulated the availability of tobacco products [4]. Similar longitudinal analyses did not yield significant interaction effects efforts are needed to regulate the availability of HPF, in light of our between tobacco ownership and year, which may have indicated evidence indicating that the same tobacco companies may have been product reformulation. The discrepancy may be due to differences in influential in shifting the profile of US foods towards greater hyper- food items that (1) directly matched based on tobacco ownership sta- palatability. tus in 1988; and (2) matched longitudinally in 1988 and 2001. Further work involving historical analysis of tobacco documents in the UCSF AUTHOR CONTRIBU TIONS Industry Documents Library may identify ways in which tobacco com- Tera L. Fazzino: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (lead); inves- panies considered product formulation and the degree of company tigation (lead); methodology (equal); supervision (lead); writing—origi- intent in potential reformulations. Given that the Industry Documents nal draft (lead). Daiil Jun: Data curation (equal); investigation (equal); Library contains millions of documents with varied content, format methodology (equal); validation (supporting); visualization (support- and text form (e.g. meeting notes, e-mail exchanges, hand-written ing); writing—review and editing (equal). Lynn Chollet-Hinton: Formal notes in the margins of report documents), machine-learning models analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (equal); with natural language processing methods may facilitate document supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); visualization (sup- review and novel discovery of tobacco industry activities that may porting); writing—review and editing (equal). Kayla Bjorlie: Validation have directly impacted the US food environment. Addressing tobacco (equal); visualization (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). industry involvement in the food system also relates to broader commercial determinants of health, providing an example of ways in which AC KNOW LEDG EME NT S one industry may have substantial involvement in seemingly unrelated None. public health risk. In this regard, researchers have recently called for expanding considerations of commercial determinants of health DECLARATION OF INTERESTS beyond the examination of single industries or single products [43], None. and the work reported in this study presents an example of ways to engage with the complexity of cross-industry activities. Future work DATA AVAILABILITY STAT EMEN T in this and other areas should embrace the interconnections among Data are available upon request from the lead author. industries to more clearly understand the collective drivers of public health harms. The study had several limitations. First, the primary analyses were conducted on a longitudinal data set that was constructed among sev- ET HICS S TAT E MENT No data from human subjects were used in the study; all data are publicly available from the USDA/CDC. eral USDA data sets that were not explicitly designed for integration. As a result, our study includes a subset of items that were tobacco- ORCID owned and suitable for matching. However, the foods were highly Tera L. Fazzino https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2896-9791 representative of the overall product lines and highest volume sales from PM and RJR from 1988 to 2001 [17, 37], thus yielding confidence in the representativeness of the data. In addition, our study RE FE RE NCE S 1. was not able to examine longitudinal change in HPF between 2001 and 2018 because there was not a sufficient overlap of foods across databases. Our cross-sectional analyses provide a current picture of the US food system and association with previous tobacco ownership, although causality cannot be inferred from our cross-sectional nor broader longitudinal analyses. 2. 3. Asch P. Consumer safety regulation: putting a price on life and limb Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1988. Amchova P, Kotolova H, Ruda-Kucerova J. Health safety issues of synthetic food colorants. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;73:914–22. Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C, Sheron N, Neal B, Thamarangsi T, et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet. 2013;381:670–9. 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 8 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. Ciresi M, Walburn R, Sutton T. Decades of deceit: document discovery in the Minnesota tobacco litigation. William Mitchell Law Rev [internet]. 1999;25(2):477–566. Available at: https://open. mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol25/iss2/10 Pringle P. The chronicles of tobacco: an account of the forces that brought the tobacco industry to the negotiating Table. William Mitchell Law Rev [internet]. 1999;25(2):387–95. Available at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol25/iss2/6 Slade J, Bero LA, Hanauer P, Barnes DE, Glantz SA. Nicotine and addiction: the Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA. 1995;274: 225–33. Lee YO, Glantz SA. Menthol: putting the pieces together. Tob Control. 2011;20:ii1–7. Nguyen KH, Glantz SA, Palmer CN, Schmidt LA. Tobacco industry involvement in children’s sugary drinks market. BMJ. 2019; 364:l736. Nguyen KH, Glantz SA, Palmer CN, Schmidt LA. Transferring racial/ethnic marketing strategies from tobacco to food corporations: Philip Morris and Kraft General Foods. Am J Public Health. 2020; 110:329–36. zxhj0223—Philip Morris Companies Inc. Annual Report 1988…— Industry Documents Library [internet]. 1988 [cited 2023 Jul 3]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/#id= zxhj0223. Accessed 3 Mar 2022. rfvw0229—Fact Sheet—Food Industry Documents RJ Reynolds [internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available at: https://www. industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/food/docs/#id=rfvw0229. Accessed 3 Mar. myng0099—RJ Reynolds Industries 1979 (790000) Annual Report…—Truth Tobacco Industry Documents [internet]. 1979 [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf. edu/tobacco/docs/#id=myng0099. Accessed 3 Mar. ryjh0062—Annual Reports RJR Nabisco—Truth Tobacco Industry Documents [internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 30]. Available at: https:// www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=ryjh0062. Accessed 20 Feb. yjhj0223—Philip Morris Companies Inc. (19990000) Annual Report…—Truth Tobacco Industry Documents [internet]. 1999 [cited 2023 Jul 12]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf. edu/tobacco/docs/#id=yjhj0223. Accessed 6 Jan. njhg0188—RJR Nabisco 1997 (970000) Operating Plan—Truth Tobacco Industry Documents [internet]. 1997 [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/ docs/#id=njhg0188. Accessed 29 Mar. pfnw0189—10-K Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 and 1…—Truth Tobacco Industry Documents [internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/ tobacco/docs/#id=pfnw0189. Accessed 23 Feb 2022. sfdv0082—Securities and Exchange Commission Form 10-K AN…—Truth Tobacco Industry Documents [internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/ tobacco/docs/#id=sfdv0082. Accessed 11 Mar. Fazzino TL. The reinforcing natures of hyper-palatable foods: behavioral evidence for their reinforcing properties and the role of the US Food industry in promoting their availability. Curr Addict Rep. 2022; 9:298–306. Gearhardt AN, DiFeliceantonio AG. Highly processed foods can be considered addictive substances based on established scientific criteria. Addiction. 2023;118:589–98. Fazzino TL, Rohde K, Sullivan DK. Hyper-palatable foods: development of a quantitative definition and application to the US food system database. Obesity. 2019;27:1761–8. DiFeliceantonio AG, Coppin G, Rigoux L, Edwin Thanarajah S, Dagher A, Tittgemeyer M, et al. Supra-additive effects of combining fat and carbohydrate on food reward. Cell Metab. 2018;28:33–44.e3. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. Small DM, DiFeliceantonio AG. Processed foods and food reward. Science. 2019;363:346–7. Fazzino TL, Courville AB, Guo J, Hall KD. Ad libitum meal energy intake is positively influenced by energy density, eating rate and hyper-palatable food across four dietary patterns. Nat Food. 2023;4: 144–7. Morales I, Berridge KC. ‘Liking’ and ‘wanting’ in eating and food reward: brain mechanisms and clinical implications. Physiol Behav. 2020;227:113152. Gilbert JR, Burger KS. Neuroadaptive processes associated with palatable food intake: present data and future directions. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;9:91–6. Demeke S, Rohde K, Chollet-Hinton C, Sutton C, Kong K, Fazzino T. Change in hyper-palatable food availability in the US food system over 30 years: 1988 to 2018. Public Health Nutr. 2022;26: 182–9. University of California San Francisco. Industry Documents Library [internet] [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available at: https://www. industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/ US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (Hyattsville, MD). [internet] [cited 2021 Oct 22]. What We Eat in America, NHANES III (1988–1994). Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes3/default.aspx. Accessed 12 Jan 2022. USDA Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for standard reference, release 11 [internet]. United States department of Agriculture; 1997 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available at: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsvillemd-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/methods-andapplication-of-food-composition-laboratory/mafcl-site-pages/sr11sr28/. Accessed 11 Feb 2022. USDA Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 12 [internet]. US Department of Agriculture; 1998. Available at: https://www.ars.usda. gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutritionresearch-center/methods-and-application-of-food-compositionlaboratory/mafcl-site-pages/sr11-sr28/. Accessed 11 Apr 2022. USDA Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 13 [internet]. US Department of Agriculture; 1999 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available at: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/ beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/methods-and-applicationof-food-composition-laboratory/mafcl-site-pages/sr11-sr28/. Accessed 8 Mar 2022. USDA Agricultural Research Service. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 2001–2002 [internet]. Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center; 2002. Available at: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/ food-and-nutrient-database-dietary-studies-fndds. Accessed 29 May 2022. Pehrsson P, Haytowitz D, McKillop K, Moore G, Finley J, Fukagawa N. USDA branded food products database Beltsville, MD: USDA Agricultural Research Service; 2018. Fazzino TL, Dorling JL, Apolzan JW, Martin CK. Meal composition during an ad libitum buffet meal and longitudinal predictions of weight and percent body fat change: the role of hyper-palatable, energy dense, and ultra-processed foods. Appetite. 2021;167: 105592. Bjorlie K, Forbush KT, Chapa DAN, Richson BN, Johnson SN, Fazzino TL. Hyper-palatable food consumption during binge-eating episodes: a comparison of intake during binge eating and restricting. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55:688–96. Gearhardt AN, Davis C, Kuschner R, Brownell KD. The addiction potential of hyperpalatable foods. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4: 140–5. 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 9 TOBACCO COMPANIES AND HPF 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. FAZZINO ET AL. ymbl0000—Philip Morris Companies Inc. Five Year Plan 890…— Industry Documents Library [internet]. 1993 [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available at: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/#id= ymbl0000. Accessed 7 Feb 2022. Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food? Milbank Q. 2009;87:259–94. Chopra M, Darnton-Hill I. Tobacco and obesity epidemics: not so different after all? BMJ. 2004;328:1558–60. Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:505–8. Johnson RK, Frary C. Choose beverages and foods to moderate your intake of sugars: the 2000 dietary guidelines for Americans—What’s all the fuss about? J Nutr. 2001;131:2766S–2771S. Moss M. Salt, sugar, fat: how the food giants hooked us [internet]. New York, NY: Random House Trade; 2014 [cited 2019 May 21] 480 p. Available at: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/ 209536/salt-sugar-fat-by-michael-moss/9780812982190 43. Lacy-Nichols J, Nandi S, Mialon M, McCambridge J, Lee K, Jones A, et al. Conceptualising commercial entities in public health: beyond unhealthy commodities and transnational corporations. Lancet. 2023;401:1214–28. SUPPORTING INF ORMATION Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article. How to cite this article: Fazzino TL, Jun D, Chollet-Hinton L, Bjorlie K. US tobacco companies selectively disseminated hyper-palatable foods into the US food system: Empirical evidence and current implications. Addiction. 2023. https:// doi.org/10.1111/add.16332 13600443, 0, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16332 by Universidad de Vigo, Wiley Online Library on [11/09/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License 10