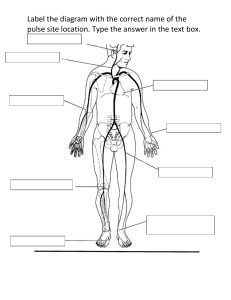

Physical Diagnostics – Vascular Examination DR.LIKA KHORBALADZE Vascular system: The vascular system is made up of the vessels that carry blood and lymph fluid through the body. It's also called the circulatory system. The arteries and veins carry blood all over the body. They send oxygen and nutrients to the body tissues. And they take away tissue waste. The lymph vessels carry lymphatic fluid. This is a clear, colorless fluid made of water and blood cells. The lymphatic system is part of the immune system that helps rid the body of toxins and waste. It does this by filtering and draining lymph away from each region of the body. Vascular system: The vessels of the blood circulatory system are: Arteries. These are blood vessels that carry oxygenated blood away from the heart to the body. Veins. These are blood vessels that carry blood from the body back into the heart. Capillaries. These are tiny blood vessels between arteries and veins that distribute oxygen-rich blood to the body. Lymphatic vessels: vessels that carry Lymph. Examination: History Taking • • • • • Age & Sex Limbs affected Bilateral or Unilateral Mode of onset Pain: Intermittent Claudication - is muscle pain that happens when person is active and stops when one rest. It's usually a symptom of blood flow problems like peripheral artery disease. Rest pain Examination: History Taking • Effect of heat, cold, emotional stress. • History of Superficial Phlebitis • Past Medical History: Embolism Myocardial Infarction Diabetes Mellitus Examination: History Taking • Trauma Accidents - fractures, Injury to the arms or legs; Changes in the muscles or ligaments Stabs - straight trauma of vessels Gunshot – primary and secondary injury of vessels Examination: History Taking • Personal History: – Smoking. – Fatty Diet – Poor Lifestyle – no exercise • Impotence • Occupational history – sedentary lifestyle General Examination: General inspection: How does patient look? ➢ pain in the thigh, calf or buttocks while or exercising. walking ➢Pale or bluish skin ➢Lack of leg hair or toenail growth ➢Sores on toes, feet, or legs that heal slowly or not at all ➢Decreased skin temperature, or thin, brittle, shiny skin on the legs and feet ➢Weak pulses in the legs and the feet ➢Gangrene ➢Impotence ➢ Wounds that won’t heal over pressure points, such as heels or ankles ➢Numbness, weakness, or heaviness in muscles ➢Burning or aching pain at rest, commonly in the toes and at night while lying flat ➢Restricted mobility ➢Thickened, opaque toenails ➢Varicose veins Physical Examination • Inspection • Palpation • Auscultation • Comparison • Special tests Inspection: Inspect and compare the upper limbs: Peripheral cyanosis: bluish discolouration of the skin associated with low SpO2 in the affected tissues (e.g. may be present in the peripheries in PVD due to poor perfusion). Peripheral pallor: a pale colour of the skin that can suggest poor perfusion (e.g. PVD). Tar staining: caused by smoking, a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease (e.g. PVD, coronary artery disease, hypertension). Xanthomata: raised yellow cholesterol-rich deposits that are often noted on the palm, tendons of the wrist and elbow. Xanthomata are associated with hyperlipidaemia (typically familial hypercholesterolaemia), another important risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Gangrene: tissue necrosis secondary to inadequate perfusion. Typical appearances include a change in skin colour (e.g. red, black) and breakdown of the associated tissue. Inspection: Inspect and compare the lower limbs: colour (e.g. red, black) and breakdown of the associated tissue. • Peripheral cyanosis: bluish discolouration of the skin associated with low SpO2 in the affected tissues (e.g. may • Missing limbs, toes, fingers: due to amputation secondary to critical ischaemia. be present in the peripheries in PVD due to poor perfusion). • Scars: may indicate previous surgical procedures (e.g. bypass surgery) or healed ulcers. • Peripheral pallor: a pale colour of the skin that can suggest poor perfusion. • Hair loss: associated with PVD due to chronic impairment of tissue perfusion. • Ischaemic rubour: a dusky-red discolouration of the leg that typically develops when the limb is dependent. Ischaemic rubour occurs due to the loss of capillary tone • Muscle wasting: associated with chronic peripheral vascular disease. associated with PVD. • Xanthomata: raised yellow cholesterol-rich deposits that • Venous ulcers: typically large and shallow ulcers with irregular borders that are only mildly painful. These ulcers may be present over the knee or ankle. Xanthomata are associated with hyperlipidaemia (typically familial most commonly develop over the medial aspect of the hypercholesterolaemia), another important risk factor for ankle. cardiovascular disease. • Arterial ulcers: typically small, well-defined, deep ulcers • Paralysis: critical limb ischaemia can cause weakness and that are very painful. These ulcers most commonly paralysis of a limb. To perform a quick gross motor develop in the most peripheral regions of a limb (e.g. the assessment, ask the patient to wiggle their toes. ends of digits). • Gangrene: tissue necrosis secondary to inadequate perfusion. Typical appearances include a change in skin Certain physical appearances should always prompt an awareness of cardiac abnormalities Genetic disorder Associated cardiac manifestation Marfan's syndrome Aortic regurgitation (aortic dissection) Down's syndrome ASD, VSD Turner's syndrome Coarctation of the aorta Spondyloarthritides, eg, ankylosing spondylitis Aortic regurgitation ASD: atrial septal defect; VSD: ventricular septal defect Facial signs associated with cardiac conditions Facial sign Description Possible cardiac association Malar flush Redness around the cheeks Mitral stenosis Xanthomata Yellowish deposits of lipid around the eyes, palms, or tendons Hyperlipidemia Corneal arcus A ring around the cornea Age, hyperlipidemia Proptosis Forward projection or displacement of the eyeball; occurs in patients with Graves' disease Atrial fibrillation Palpation: Temperature Place the dorsal aspect of your hand onto the patient’s upper limbs to assess temperature: •In healthy individuals, the upper limbs should be symmetrically warm, suggesting adequate perfusion. •A cool and pale limb is indicative of poor arterial perfusion. Capillary refill time (CRT) Measuring capillary refill time (CRT) in the hands is a useful way of assessing peripheral perfusion: •Apply five seconds of pressure to the distal phalanx of one of a patient’s fingers and then release. •In healthy individuals, the initial pallor of the area you compressed should return to its normal colour in less than two seconds. •A CRT that is greater than two seconds suggests poor peripheral perfusion. •Prior to assessing CRT, check that the patient does not currently have pain in their fingers. Palpation: Taking the pulse - Taking the pulse is one of the simplest, oldest, and yet most informative of all clinical tests. Peripheral signs associated with infective endocarditis Peripheral sign Description Cardiac association Clubbing Broadening or thickening of the Infective endocarditis, cyanotic tips of the fingers (and toes) with congenital heart disease increased lengthwise curvature of the nail and a decrease in the angle normally seen between the cuticle and the fingernail Splinter hemorrhages Streak hemorrhages in nailbeds Infective endocarditis Janeway lesions Macules on the back of the hand Infective endocarditis Osler's nodes Tender nodules in fingertips Infective endocarditis Palpation: Taking the pulse - Abnormal pulses Type of pulse Pulse characteristics Most likely cause Regularly irregular – 2nd-degree heart block, ventricular bigeminy Irregularly irregular – Atrial fibrillation, frequent ventricular ectopics Slow rising Low gradient upstroke Aortic stenosis Waterhammer, collapsing Steep up and down stroke (lift arm so that wrist is above heart height) Aortic regurgitation, patent ductus arteriosus Bisferiens A double-peaked pulse – the second peak can be smaller, larger, or the same size as the first Aortic regurgitation, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Pulsus paradoxus An exaggerated fall in pulse volume on inspiration (>10 mm Hg on sphygmomanometry) Cardiac tamponade, acute asthma Bounding Large volume Anemia, hepatic failure, type 2 respiratory failure (high CO2) Pulsus alternans Alternating large and small volume pulses Bigeminy Peripheral pulses: Radial pulse Palpate the patient’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery. Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm, palpating for at least 5 cardiac cycles. Brachial pulse Palpate the brachial pulse in each arm, assessing volume and character: •Support the patient’s right forearm with your left hand. •Position the patient so that their upper arm is abducted, their elbow is partially flexed and their forearm is externally rotated. •With your right hand, palpate medial to the biceps brachii tendon and lateral to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. •Deeper palpation is required (compared to radial pulse palpation) due to the location of the brachial artery. Peripheral pulses Peripheral pulses should also be documented, as peripheral vascular disease is an important predictor of coronary artery disease: •femoral – feel at the midinguinal point (midway between the symphysis pubis and the anterior superior iliac spine, just inferior to the inguinal ligament) •popliteal – feel deep in the center of the popliteal fossa with the patient lying on their back with their knees bent •posterior tibial – feel behind the medial malleolus •dorsalis pedis – feel over the second metatarsal bone just lateral to the extensor hallucis tendon Blood pressure (BP) Measure the patient’s blood pressure in both arms Wide pulse pressure (more than 100 mmHg of difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure) can be associated with aortic regurgitation and aortic dissection. A more than 20 mmHg difference in BP between arms is abnormal and is associated with aortic dissection. Palpate the carotid pulse If no bruits were identified, proceed to carotid pulse palpation: 1. Ensure the patient is positioned safely on the bed, as there is a risk of inducing reflex bradycardia when palpating the carotid artery (potentially causing a syncopal episode). 2. Gently place your fingers between the larynx and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to locate the carotid pulse. 3. Assess the character (e.g. slow-rising, thready) and volume of the pulse. Sensation Slowly progressive peripheral neuropathy is common in patients with significant peripheral vascular disease. This results in a glove and stocking distribution of sensory loss. Acute critical limb ischaemia causes rapid onset parathesia in the affected limb. Gross peripheral sensation assessment Perform a gross assessment of peripheral sensation: 1. Ask the patient to close their eyes whilst you touch their sternum with a wisp of cotton wool to provide an example of light touch sensation. 2. Ask the patient to say “yes” when they feel the sensation. 3. Using the wisp of cotton wool, begin to assess light touch sensation moving distal to proximal, comparing each side as you go by asking the patient if it feels the same: If sensation is intact distally, no further assessment is required. If there is a sensory deficit, continue to move proximally until the patient is able to feel the cotton wool and note the level at which this occurs. Auscultation: Auscultate the carotid artery Prior to palpating the carotid artery, you need to auscultate the vessel to rule out the presence of a bruit. The presence of a bruit suggests underlying carotid stenosis, making palpation of the vessel potentially dangerous due to the risk of dislodging a carotid plaque and causing an ischaemic stroke. Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope between the larynx and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle over the carotid pulse and ask the patient to take a deep breath and then hold it whilst you listen. Be aware that at this point in the examination, the presence of a ‘carotid bruit’ may, in fact, be a radiating cardiac murmur (e.g. aortic stenosis). Auscultation Auscultate the aorta and renal arteries Auscultate over the aorta and renal arteries to identify vascular bruits suggestive of turbulent blood flow: Aortic bruits: auscultate 1-2 cm superior to the umbilicus, a bruit here may be associated with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Renal bruits: auscultate 1-2 cm superior to the umbilicus and slightly lateral to the midline on each side. A bruit in this location may be associated with renal artery stenosis. Special Tests: Modified Allen’s test To perform a modified Allen’s test: 1. Ask the patient to clench their fist. 2. Apply pressure over the radial and ulnar artery to occlude both vessels. 3. Ask the patient to open their hand, which should now appear blanched. If the hand does not appear it suggests you are not completely occluding the arteries with your fingers. 4. Remove the pressure from the ulnar artery whilst maintaining pressure over the radial artery. 5. If there is adequate blood supply from the ulnar artery, the normal colour should return to the entire hand within 5-15 seconds. If the return of colour takes longer, this suggests poor collateral circulation Do not perform arterial blood gas sampling on a hand that does not appear to have an adequate collateral blood supply. It should be noted that there is no evidence performing this test reduces the rate of ischaemic complications of arterial sampling. Special Tests: Adson's Test Purpose of Test: Test for the presence of Thoracic Outlet syndrome, specifically compression between the Anterior and Middle Scalene Muscles. Test Position: Standing. Performing the Test: Palpate the radial pulse on the affected side with the elbow fully extended. Have the patient rotate their head to the side being tested and extend the neck. Next, abduct, extend, and laterally rotate the shoulder. From this position, have the patient take a deep breath and hold. Assess the pulse response. A positive test is a decrease in pulse vigor from the starting position to the final position. Importance of Test: Patients with Vascular types of thoracic outlet syndrome often describe their pain as a fullness, heaviness, clumsiness, or weakness in their arm. The patient may also have subjective complaints of swelling, either permanent or intermittent. When performing Adson's Test, the examiner is placing the patient in a position that compresses the subclavian artery between the anterior and middle scalene, thus resulting in a decrease in pulse strength. When performing Adson's Test, it is important to test the contralateral side as well to understand the patient's normal radial pulse. Special Tests: Buerger’s test Buerger’s test is used to assess the adequacy of the arterial supply to the leg. To perform Buerger’s test: 1. With the patient positioned supine, stand at the bottom of the bed and raise both of the patient’s feet to 45º for 1-2 minutes. 2. Observe the colour of the limbs: The development of pallor indicates that peripheral arterial pressure is unable to overcome the effects of gravity, resulting in loss of limb perfusion. If a limb develops pallor, note at what angle this occurs (e.g. 25º), this is known as Buerger’s angle. In a healthy individual, the entire leg should remain pink, even at an angle of 90º. A Buerger’s angle of less than 20º indicates severe limb ischaemia. 3. Sit the patient up and ask them to hang their legs down over the side of the bed: Gravity should now aid reperfusion of the leg, resulting in the return of colour to the patient’s limb. The leg will initially turn a bluish colour due to the passage of deoxygenated blood through the ischaemic tissue. Then the leg will become red due to reactive hyperaemia secondary to post-hypoxic arteiolar dilatation (driven by anaerobic metabolic waste products). Ankle-brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) Measurement Measure the brachial pressure 1. With the patient lying on the examination couch, place the sphygmomanometer cuff over the left arm proximal to the brachial artery and position the Doppler probe on the brachial artery at a 45° angle (medial to the biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa). 2. Inflate the cuff 20-30 mmHg above the pressure at which the Doppler pulse is no longer audible and then deflate the cuff slowly, noting the pressure at which you first detect a pulse from the Doppler. This represents the systolic pressure in the vessel being assessed. 3. Now repeat steps 1 and 2 on the right brachial artery to assess systolic pressure. 4. Record the higher of the two systolic readings for use when calculating ABPI. Ankle-brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) Measurement Measure the ankle pressure 1. Place the sphygmomanometer on the left ankle and position the Doppler probe over the posterior tibial artery, which is located posterior to the medial malleolus. 2. Inflate the cuff 20-30 mmHg above the pressure at which the Doppler pulse is no longer audible and then deflate the cuff slowly, noting the pressure at which you first detect a pulse from the Doppler. This represents the systolic pressure in the vessel being assessed. 3. Keep the sphygmomanometer in the same location but re-position the Doppler probe over the dorsalis pedis artery of the left foot, which is located lateral to the extensor hallucis longus tendon. 4. Assess the systolic pressure in the dorsalis pedis artery of the left foot by repeating step 2. 5. Record the highest of the two pressures obtained from dorsalis pedis (DP) and the posterior tibial artery (PTA) for use when calculating the left ABPI. 6. Repeat the same process on the right leg to calculate the right ABPI. Calculate ABPI BPI Interpretation >1.2 Calcified vessels often cause unusually high ABPI results. In this scenario, further assessments such as duplex ultrasound and angiography are advised to accurately assess perfusion. Left ABPI = (highest pressure of either left PTA or DP) ÷ (highest brachial pressure) Right ABPI = (highest pressure of either right PTA or DP) ÷ (highest brachial pressure) Erroneous results can occur due to: Incorrectly positioned cuff Irregular pulse (e.g. atrial fibrillation) 1.0-1.2 Normal result Mild arterial disease: typical 0.8-0.9 presenting features include mild claudication. 0.50.79 Moderate arterial disease: typical presenting features include severe claudication. <0.5 Severe arterial disease: typical presenting features include rest pain, ulceration and gangrene. This is also known as critical limb ischaemia. Calcified vessels (e.g. diabetes) Thank you