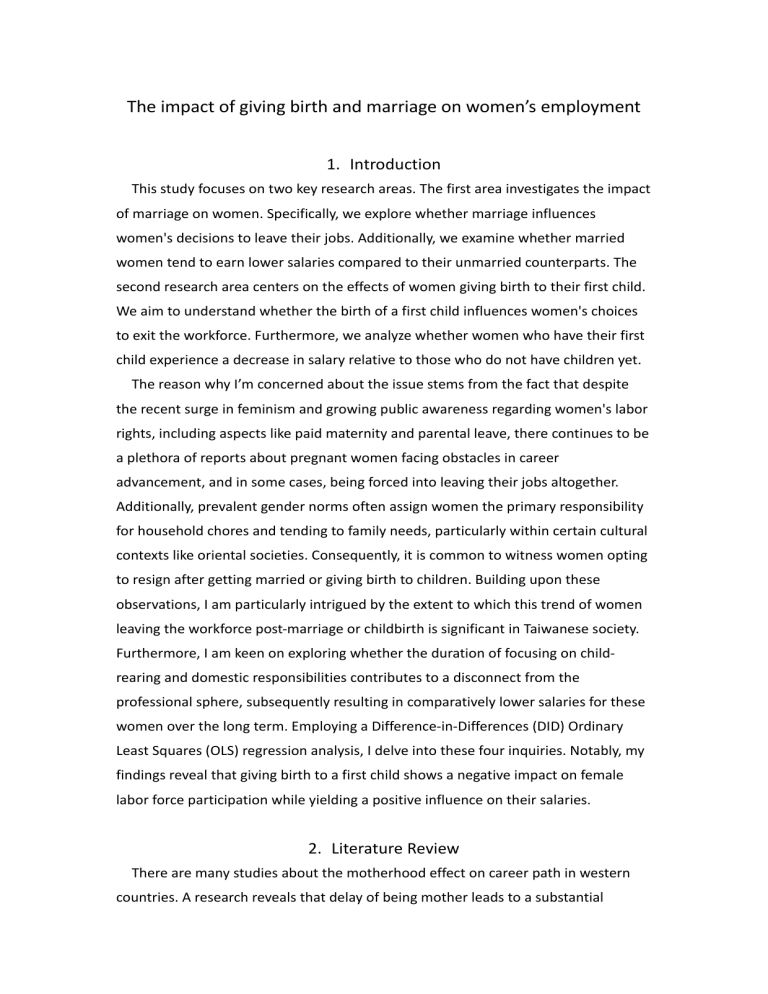

The impact of giving birth and marriage on women’s employment 1. Introduction This study focuses on two key research areas. The first area investigates the impact of marriage on women. Specifically, we explore whether marriage influences women's decisions to leave their jobs. Additionally, we examine whether married women tend to earn lower salaries compared to their unmarried counterparts. The second research area centers on the effects of women giving birth to their first child. We aim to understand whether the birth of a first child influences women's choices to exit the workforce. Furthermore, we analyze whether women who have their first child experience a decrease in salary relative to those who do not have children yet. The reason why I’m concerned about the issue stems from the fact that despite the recent surge in feminism and growing public awareness regarding women's labor rights, including aspects like paid maternity and parental leave, there continues to be a plethora of reports about pregnant women facing obstacles in career advancement, and in some cases, being forced into leaving their jobs altogether. Additionally, prevalent gender norms often assign women the primary responsibility for household chores and tending to family needs, particularly within certain cultural contexts like oriental societies. Consequently, it is common to witness women opting to resign after getting married or giving birth to children. Building upon these observations, I am particularly intrigued by the extent to which this trend of women leaving the workforce post-marriage or childbirth is significant in Taiwanese society. Furthermore, I am keen on exploring whether the duration of focusing on childrearing and domestic responsibilities contributes to a disconnect from the professional sphere, subsequently resulting in comparatively lower salaries for these women over the long term. Employing a Difference-in-Differences (DID) Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis, I delve into these four inquiries. Notably, my findings reveal that giving birth to a first child shows a negative impact on female labor force participation while yielding a positive influence on their salaries. 2. Literature Review There are many studies about the motherhood effect on career path in western countries. A research reveals that delay of being mother leads to a substantial increase in earnings of 9% per year of delay, an increase in wages of 3%, which shows that taking care of children have a large impact on female’s career (Miller 2009). Because of the incentives of delaying fertility which is associated with women career success, the fertility rate declines and women, especially those with high incomes, postpone the time they give birth to children in U.S recently (Caucutt et al. 2002). Other research studying groups of retired women also shows that the long-term benefits of delayed childbearing includes better living standards and economic wellbeing (Hofferth 1984). We all know that it isn’t easy for women to taking care of new born. So, will women quit after pregnancy? A research studies U.S employed women shows that pregnancy itself has no effect on labor force exit, while preschool children increase the hazard of labor force exit for full-time workers because it takes much time and energy to take care of small age children (Budig 2003). Another study points out additional child appears to decrease the probability that a woman will be working at any particular point in time, and each birth appears to decrease total lifetime labor force participation by one year or more (SmithLovin and Tickamyer, 1978; Cramer, 1980). Although many women chose to quit their jobs, the cost of withdrawing is very high actually. Therefore, there are some factors that affect the probability of quitting, for example, high education, wages, and job-specific training (Desai et al. 1991). Aside from giving birth to babies, many studies confirm marriage bonus for males and marriage penalty for females and show that married men’s salaries are higher than women’s on average. There are many reasons for the phenomenon, such as household specification (Hersch and Stratton, 2000), selection (Ginther and Zavodny, 2001) or employer preference (McDonald, 2020). Considering that most researches of above topics done in western countries, I try to find out the causal relation of marriage and giving birth on salary and job quit decision by using Taiwan household data in my study. Culture difference may result in different answers of same topic. Because it is mentioned above factors like education and seniority are important, I will control them in my research and further add individual and time fixed effects to control factors I can’t observe. 3. Data and Sample The data I use is Panel Study of Family Dynamics from Survey Research Data Archive (SRDA). This panel dataset tracks Taiwanese family members, primarily adults, from 1999 up to the present. The survey comprehensively explores various aspects of family dynamics, including family structure, interactions, religiosity, and many other dimensions. For this study, I select data ranging from 2010 to 2014. The specific columns used include samples’ gender, education level, marriage status, the year they get married, working status, seniority, working hour per week, the year they give birth to the first child, and salary. Throughout the data cleaning process, I remove salary outliers and all missing values, including respondents answering they didn’t know or refused to reply. 3.1 Married Sample The treatment group consists of people who got married in 2013, while the control group includes individuals who remained unmarried between 2010 and 2014. The sample selection was limited to individuals aged between 26 and 40. 3.1.1 Dependent variable – Salary In the examination of the relationship between marriage and salary, the dataset comprises a total of 1998 samples, divided into a treatment group (n = 219) and a control group (n = 1779). Below are summary statistics tables that present pretreatment and post-treatment data for different genders. For the purpose of the tables, a value of 0 denotes the control group, while a value of 1 signifies the treatment group. Among females, the treatment group consistently demonstrates higher mean salaries than the control group. Intriguingly, post-marriage, the mean salary for women in the treatment group experiences an increase of 41804 units. In contrast, the control group's female participants see a more modest increase of 1893 units, resulting in a final mean salary of 36443. For males, a similar pattern emerges, where the treatment group consistently maintains higher salaries than the control group. The salary disparity between the two groups also widens post-treatment. Table 1. Pre-treatment summary table (Female) Table 3. Pre-treatment summary table (Male) Table 2. Post treatment summary table (Female) Table 4. Post treatment summary table (Male) The covariates' summary statistics for both the treatment and control groups are presented below. Following the implementation of a two-sample t-test to compare these groups, all resulting p-values exceed 0.05. This indicates that under a 95% confidence level, the two groups are composed of samples with comparable educational levels, ages, weekly working hours, and seniority. However, t-test result of female salary before treatment shows that salary between treatment and control groups is significantly different, and that treatment group mean income is higher. Table 5. Treatment group covariates Table 6. Control group covariates 3.1.2 Dependent variable – Working status Within this dataset, the treatment group includes 254 samples, while the control group comprises 2238 samples. The variable "y_work" is used to denote participants' working status, where a value of 1 signifies active employment during the examination period, and 0 denotes the absence of a job. As we can see, a noteworthy trend emerges regarding the working rates among different groups. For women who have never been married, their working rates show an increase over a two-year period. In contrast, women who were married in 2013 demonstrate a decline in working rates following the treatment. Specifically, their working rate decreases from 0.93 prior to treatment to 0.84 post-treatment. As for males, the working rates for both the treatment and control groups remain relatively stable after the treatment period, showcasing minimal changes in either group. Table 7. Pre-treatment summary table (Female) Table 9. Pre-treatment summary table (Male) Table 8. Post treatment summary table (Female) Table 10. Post treatment summary table (Male) The summary statistics for covariates within both the treatment and control groups are outlined below. These groups possess comparable covariate characteristics, establishing similarity under t-test analysis and a 95% confidence level. Nonetheless, a distinct observation emerges when examining the working rate variable (y_work) of both genders prior to the treatment. The t-test results reveal a significant difference in the working rates of the two groups, with the mean value of the treatment group exceeding that of the control group. This discrepancy raises the possibility of selection bias, suggesting that individuals with employment might be more popular in marriage market. . Table 11. Treatment group covariates Table 12. Control group covariates 3.2 Giving Birth Sample The treatment group consists of people who gave birth to their first child in 2013 and the control group consists of people who didn’t give birth to any children from 2010 to 2014. 3.2.1 Dependent variable – Salary In the analysis of the dependent variable, salary, the control group includes 2341 samples, whereas the treatment group comprises 170 samples. Both genders' tables show treatment group samples’ salaries are slightly higher than the control group. However, a common trend emerges after the treatment intervention; salaries in both groups display a similar pattern of increase, progressing at nearly equivalent rates. Table 13. Pre-treatment summary table (Female) Table 15. Pre-treatment summary table (Male) Table 14. Post treatment summary table (Female) Table 16. Post treatment summary table (Male) Treatment and control groups have different mean age, and housework (weekly engagement in household tasks) at a 95% confidence level. Additionally, the results of the t-test indicate a significant difference in mean salary among male participants, with the treatment group displaying a higher average income. Table 17. Treatment group covariates Table 18. Control group covariates 3.2.2 Dependent variable – Working status Within this study's sample, the treatment group includes 226 samples, while the control group comprises 2936 samples. First, we examine the female participants. Prior to the treatment (birth of the first child), both groups exhibit nearly identical work rates. However, following childbirth, there is a drastic decline in work rates among women, plummeting from 0.86 to 0.61, reflecting a substantial decrease of 0.25. Conversely, among the male participants, the work rates remain relatively stable both before and after the treatment period in both groups. Table 19. Pre-treatment summary table (Female) Table 21. Pre-treatment summary table (Male) Table 20. Post treatment summary table (Female) Table 22. Post treatment summary table (Male) Under a 95% confidence level, the treatment and control groups display comparable covariate characteristics, with the exception of housework time per week, where the treatment group reports higher involvement in household tasks. Moreover, a significant divergence is observed in the work rates of males within the treatment and control groups, in which the work rate in the treatment group surpasses that of the control group. Table 23. Treatment group covariates Table 24. Control group covariates In conclusion, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations within this research. As indicated by the balanced test conducted earlier, individuals who underwent marriage or parenthood tended to possess jobs or higher salaries, implying the presence of selection bias in the data. 4. Empirical method For this study, I choose to use the Difference-in-Differences (DID) Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression method. This approach operates under the assumption that, in the absence of treatment, the outcomes of both the treatment and control groups move in a parallel way. The regression model and the meanings of the variables for the two research topics are outlined as follows. 4.1 Married (1) y_work ~ treatment + post + treat_post + education +seniority + working_hour + age + age2 (2) salary ~ treatment + post + treat_post + education +seniority + working_hour + age + age2 4.2 Giving Birth (1) y_work ~ treatment + post + treat_post + education +seniority + working_hour + age + age2 + housework (2) salary ~ treatment + post + treat_post + education +seniority + working_hour + age+ age2 + housework y_work Having a job or not, 0 for not and 1 otherwise treatment Married or giving birth to babies or not, 0 for not and 1 otherwise post 0 means post treatment data and 1 otherwise treat_post Interaction between “treatment” and “post” variables education Education level, from 1 to 15. 1 means not educated and 15 means doctoral degree seniority Years of working experience working_hour Weekly working hour housework Weekly hours devoted to household chores Table 25. Variable table To assess the assumption of equal trends, I expanded the dataset to include the year 2010, and the results are presented below. When examining the figures concerning the impact of marriage on salary as the dependent variable, they exhibit a consistent trend. However, in the case of figures with working status as the dependent variable, the trend is not uniform. This discrepancy could potentially weaken the statistical power of our regression analysis. Figure 1. Married and working status DID graph (Female) Figure 2. Married and salary DID graph (Female) Figure 3. Married and working status DID graph (Male) Figure 4. Married and salary DID graph (Male) Regarding the topic of giving birth, most figures display a consistent trend except for the one illustrating the relationship between salary and childbirth (female). Figure 5. Giving birth and working status DID graph (Female) Figure 7. Giving birth and working status DID graph (Male) Figure 6. Giving birth and salary DID graph (Female) Figure 8. Giving birth and salary DID graph (Male) 5. Results 5.1 Married 5.1.1 Working status Below is the DID regression results of two genders with covariates included or not included. The DID coefficients for both genders are not statistically significant, suggesting that getting married might not significantly impact individuals' decisions to continue with their jobs. Table 26. OLS regression result table with working status as dependent variable 5.1.2 Salary When examining the influence of marriage on salary, none of the DID coefficients are statistically significant across all genders. This suggests that the results do not align with the anticipated marriage penalty for females or marriage bonus for males. Table 27. OLS regression result table with salary as dependent variable 5.2 Giving birth to babies 5.2.1 Working status The DID coefficients for females are consistently significant (model 1 at a 95% confidence level and model 2 at 90%), with a standard error of approximately 0.2. These coefficients are -0.047 and -0.035 respectively. Conversely, the DID coefficients for males aren’t statistically significant. From column (2), we deduce that when a woman gives birth to her first child, her working rate experiences a decrease of 0.035, aligning with the findings of numerous prior studies. Table 28. OLS regression result table with working status as dependent variable 5.2.2 Salary The DID coefficient is only statistically significant at the 90% confidence level when the female model includes covariates, and none of the DID coefficients for males achieve significance. In Model 2, the DID coefficient exhibits a positive value of approximately 6351, with a standard error of 3503. This suggests that when a woman gives birth to her first child, her salary could potentially increase by NTD 6351. This finding appears unusual and divergent from most prior studies, as it contradicts the intuitive notion that women might face hindrances to career advancement or have less time available for their jobs due to the responsibilities of childcare. Table 29. OLS regression result table with salary as dependent variable 6 Discussion and Conclusion This study primarily highlights the impact of giving birth on females, affecting both salary and job retention, while no discernible influence of marriage emerges across genders. Specifically, the findings reveal that the birth of a first child exerts a negative influence on female labor force participation while having a positive effect on their salaries. This may stem from the consideration that women perceive the demands of managing childcare and work commitments as time-consuming and challenging, prompting some to opt for leaving their jobs. Additionally, cultural norms might contribute to the decrease in work rates after giving birth, as they frequently assign women the primary responsibility for childcare. However, the unexpected result of the relationship between giving birth and salary needs further investigation. However, there are certain limitations to this research. Firstly, extending the duration of the data collection period is necessary to effectively observe these effects. Specifically, I believe that the impact of marriage might not become immediately apparent within just one year after the treatment occurs. Secondly, the potential for omitted bias exists, including factors such as personality, job quality, socioeconomic status, and more. I intend to incorporate entity or time fixed effects to mitigate this concern in the future. Furthermore, it's important to note that the size of the treatment group samples is quite limited. Lastly, the issue of selection bias arises due to the possibility that both marriage and giving birth involve a selective process. As a result, the individuals within the treatment and control groups might inherently possess different characteristics.