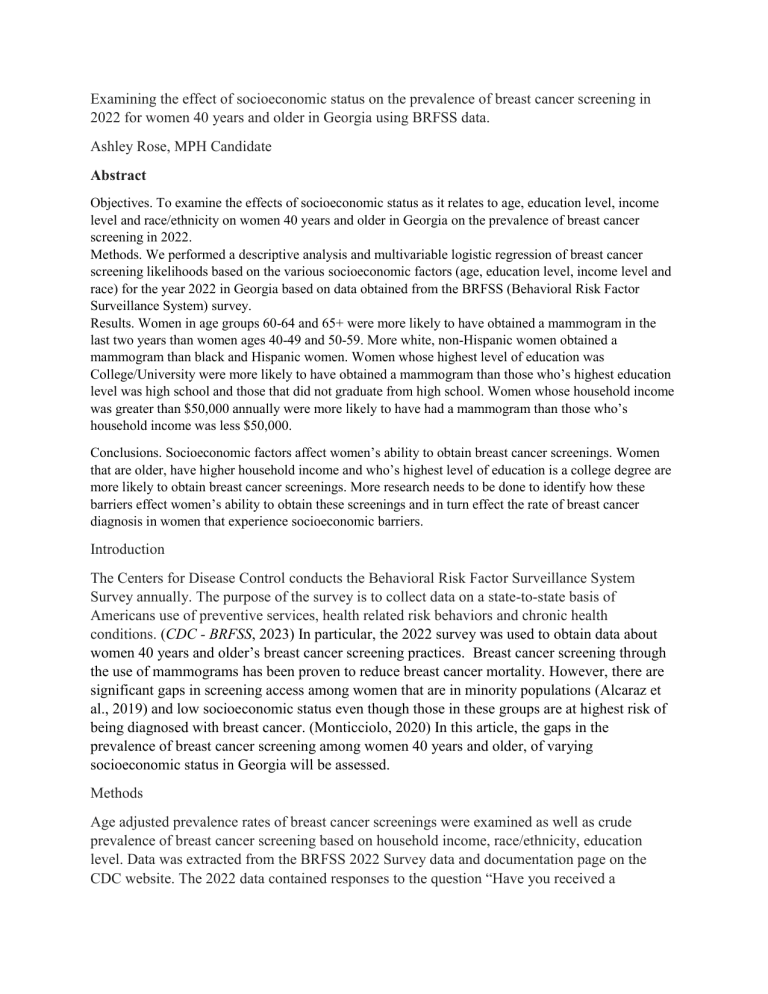

Examining the effect of socioeconomic status on the prevalence of breast cancer screening in 2022 for women 40 years and older in Georgia using BRFSS data. Ashley Rose, MPH Candidate Abstract Objectives. To examine the effects of socioeconomic status as it relates to age, education level, income level and race/ethnicity on women 40 years and older in Georgia on the prevalence of breast cancer screening in 2022. Methods. We performed a descriptive analysis and multivariable logistic regression of breast cancer screening likelihoods based on the various socioeconomic factors (age, education level, income level and race) for the year 2022 in Georgia based on data obtained from the BRFSS (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) survey. Results. Women in age groups 60-64 and 65+ were more likely to have obtained a mammogram in the last two years than women ages 40-49 and 50-59. More white, non-Hispanic women obtained a mammogram than black and Hispanic women. Women whose highest level of education was College/University were more likely to have obtained a mammogram than those who’s highest education level was high school and those that did not graduate from high school. Women whose household income was greater than $50,000 annually were more likely to have had a mammogram than those who’s household income was less $50,000. Conclusions. Socioeconomic factors affect women’s ability to obtain breast cancer screenings. Women that are older, have higher household income and who’s highest level of education is a college degree are more likely to obtain breast cancer screenings. More research needs to be done to identify how these barriers effect women’s ability to obtain these screenings and in turn effect the rate of breast cancer diagnosis in women that experience socioeconomic barriers. Introduction The Centers for Disease Control conducts the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey annually. The purpose of the survey is to collect data on a state-to-state basis of Americans use of preventive services, health related risk behaviors and chronic health conditions. (CDC - BRFSS, 2023) In particular, the 2022 survey was used to obtain data about women 40 years and older’s breast cancer screening practices. Breast cancer screening through the use of mammograms has been proven to reduce breast cancer mortality. However, there are significant gaps in screening access among women that are in minority populations (Alcaraz et al., 2019) and low socioeconomic status even though those in these groups are at highest risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer. (Monticciolo, 2020) In this article, the gaps in the prevalence of breast cancer screening among women 40 years and older, of varying socioeconomic status in Georgia will be assessed. Methods Age adjusted prevalence rates of breast cancer screenings were examined as well as crude prevalence of breast cancer screening based on household income, race/ethnicity, education level. Data was extracted from the BRFSS 2022 Survey data and documentation page on the CDC website. The 2022 data contained responses to the question “Have you received a mammogram in the last two years” so comparison between previous two years was not done. The data file was converted from XPT format and imported into SAS 9.4 for data analysis. Each variable was age adjusted. Socioeconomic status has a multitude of definitions, in this case the focus was on race/ethnicity. Education, and income level. Race/ethnicity was defined as White, non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic. P values were calculated using chi squares tests. Results Age Adjusted Odds ratios were estimated for the based on the BRFSS survey data for 2022. Odds ratios for Age group were produced by comparing the likelihood of each age group to have obtained a mammogram to age group 40-49. Based on this, women 65+ (1.74 AOR) were more likely to have had a mammogram. White, non-Hispanic women were more likely than Hispanic women to obtain a mammogram (AOR 1.26 vs 0.671 respectively). Black women were more likely to have obtained a mammogram than both white and Hispanic women. Women whose highest level of education is a college degree is more likely to obtain a mammogram than those with less than a high school diploma and those with a high school diploma. Women whose annual household income was over $100,000 were more likely to obtain a mammogram than those whose income was $15,0000-$24,999 (AOR 2.74 vs 1.3). The p.value yielded for each category was less than the level of significance indicating that the likelihood of women over the age of 40 in Georgia obtaining a mammogram varies based on socioeconomic status. Table 1. Age Adjusted Prevalence and Odds Ratios for Breast Cancer Screening Rates Based on Socioeconomic Status defined by income level, education level and race/ethnicity. Have you obtained a mammogram in the last two years? Age Adjusted Prevalence 95% C.I. Age Adjusted Odds Ratio(C.I.) Yes (n(%)) No (n(%) AOR (CI) 40-49 338(60.6) 184(39.4) 0.67(0.36,1.26) 50-59 510(71.9) 199(28.1) 1.45(1.06,1.99) 60-64 355(79.3) 105(20.8) 1.65(1.15,2.37) 65+ 1449(74.9) 494(25.1) 1.74(1.232,2.45) Race/Ethnicity White, non Hispanic Black, non Hipsanic 1761(69.8) 720(30.2) 1.26(1.03,1.56) 745(76.9) 186(23.1) 1.84(0.41,8.26) Age Group Hispanic 71(66.4) 33(33.6) 0.671(0.359,1.26) 156(56.1) 108(43.9) 1.00(0.724,1.43) 626(68.6) 239(31.4) 1.33(0.94,1.87) 1116(78.4) 332(21.6) 1.9(1.35,2.68) 257(60.4%) 159(39%) 1.3(0.74,2.36) 259(63.7) 108(36.3) 0.74(0.44,1.26) 35,000-49,999 293(67.4) 102(32.6) 0.965(0.58,1.60) 50,000-99,999 100,000199,999 613(73.2) 198(26.8) 1.65(1.01,2.69) 369(79.2) 90(20.8) 2.74(1.57,4.79) Education Level Less than Highschool High School diploma College Degree Household Income 15,00024,9999 25,000034,999 Discussion Overall, the prevalence of breast cancer screening through mammography is higher among those that would be of higher socioeconomic status. Of note, women of Hispanic descent, women with less than a high school diploma and women whose income is less than $50,000 per year are far less likely to obtain a mammogram. A higher prevalence of screening was seen in Black nonHispanic women than in white women, a noteworthy change that can be attributed to successful intervention strategies such a local campaign geared towards minority women like the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. (Li et al., 2020) Although white women have a higher incidence of breast cancer, black women experience higher rates of breast cancer mortality, thus why they are programs tailored for targeted education, outreach and preventive screening services. (Breast Cancer Facts & Figures, n.d.) This study has limitations as factors such as health insurance, type of coverage, recommendation guidelines, transportation access and specific geographic factors were not included in the analysis. (Castaldi et al., 2022) All factors that could be considered under the scope of socioeconomic status can potentially affect a woman’s level of accessibility to preventive screenings. The survey data was also collected using a landline-based phone survey method which means that respondents would be limited to women that have this kind of telephone in their home. Nonetheless, this analysis displays a difference in breast cancer screening prevalence across various socioeconomic factors which can lead to further research to detail why this is, the impact it has on mortality rates and possible interventions that can be performed. Public Health Implications. More research to examine the impact of other factors such as recommendation guidelines should be addressed. Age can introduce bias in these rates due to such guidelines. Adjustments to the guidelines accordingly can potentially have an impact on the prevalence of preventive breast cancer screenings as it relates to age. Interventions need to be developed with the thought of systemic racial and cultural barriers in mind. Such data can be useful in informing policies and surveillance methods for improvement in the uptake of preventive screenings among this population. (Monticciolo et al., 2018) References Alcaraz, K. I., Wiedt, T. L., Daniels, E., Yabroff, K. R., Guerra, C. E., & Wender, R. C. (2019). Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21586 Breast cancer facts & figures. (n.d.). American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-figures.html Castaldi, M., Smiley, A., Kechejian, K., Butler, J., & Latifi, R. (2022). Disparate access to breast cancer screening and treatment. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01793-z CDC - BRFSS. (n.d.). https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html Li, L., Ji, J., Besculides, M., Bickell, N. A., Margolies, L., Jandorf, L., Taioli, E., Mazumdar, M., & Liu, B. (2020). Factors associated with mammography use: A side‐by‐side comparison of results from two national surveys. Cancer Medicine, 9(17), 6430–6451. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3128 Monticciolo, D. L. (2020). Current guidelines and gaps in breast cancer screening. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 17(10), 1269–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.002 Monticciolo, D. L., Newell, M. S., Moy, L., Niell, B. L., Monsees, B., & Sickles, E. A. (2018). Breast cancer screening in Women at Higher-Than-Average Risk: Recommendations from the ACR. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 15(3), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2017.11.034