Mary-Jane Schneider - Introduction to Public Health-Jones & Bartlett Learning

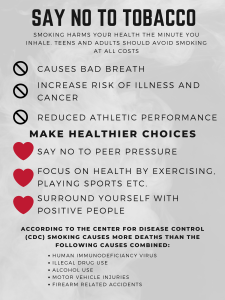

advertisement