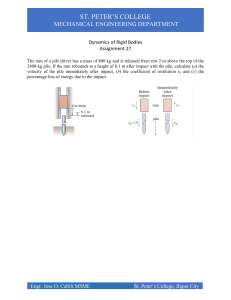

Technical Manual for LPile 2016 (Using Data Format Version 9) A Program for the Analysis of Deep Foundations Under Lateral Loading by William M. Isenhower, Ph.D., P.E. Shin-Tower Wang, Ph.D., P.E. L. Gonzalo Vasquez, Ph.D., P.E. January 14, 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Ensoft, Inc. All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of Ensoft, Inc. Date of Last Revision: January 14, 2016 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... xiii Chapter 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 1-1 Compatible Designs .............................................................................................................. 1 1-2 Principles of Design.............................................................................................................. 1 1-2-1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1-2-2 Modelling of Nonlinear Response of Soil ..................................................................... 2 1-2-3 Limit States ................................................................................................................... 2 1-2-4 Step-by-Step Procedure ................................................................................................. 2 1-2-5 Suggestions for the Designing Engineer ....................................................................... 3 1-3 Modeling a Pile Foundation ................................................................................................. 5 1-3-1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 1-3-2 Example Model of Individual Pile with Axial and Lateral Loading ............................. 7 1-3-3 Computation of Foundation Stiffness ........................................................................... 8 1-3-4 Concluding Comments .................................................................................................. 9 1-4 Organization of Technical Manual ....................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading ............................................................ 11 2-1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 11 2-1-1 Influence of Pile Installation and Loading on Soil Characteristics ............................. 11 2-1-2 Models Used in Analyses of Laterally Loaded Single Piles ....................................... 14 2-1-3 Computational Approach for Single Piles ................................................................... 21 2-1-4 Pile Buckling Analysis ................................................................................................ 22 2-1-5 Analysis of Critical Pile Length .................................................................................. 23 2-1-6 Occurrences of Lateral Loads on Piles ........................................................................ 24 2-2 Derivation of Differential Equation for the Beam-Column and Methods of Solution ....... 30 2-2-1 Derivation of the Differential Equation ...................................................................... 30 2-2-2 Solution of Reduced Form of Differential Equation ................................................... 34 2-2-3 Solution by Finite Difference Equations ..................................................................... 40 Chapter 3 Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock ......................................................... 49 3-1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 49 3-2 Experimental Measurements of p-y Curves........................................................................ 51 3-2-1 Direct Measurement of Soil Response ........................................................................ 51 3-2-2 Derivation of Soil Response from Moment Curves Obtained by Experiment ............ 51 3-2-3 Nondimensional Methods for Obtaining Soil Response ............................................. 53 3-3 p-y Curves for Cohesive Soils ............................................................................................ 54 3-3-1 Initial Slope of Curves................................................................................................. 54 3-3-2 Analytical Solutions for Ultimate Lateral Resistance ................................................. 57 3-3-3 Influence of Diameter on p-y Curves .......................................................................... 63 3-3-4 Influence of Cyclic Loading ........................................................................................ 64 iii 3-3-5 Introduction to Procedures for p-y Curves in Clays .................................................... 66 3-3-6 Procedures for Computing p-y Curves in Clay ........................................................... 69 3-3-7 Response of Soft Clay in the Presence of Free Water................................................. 69 3-3-8 Response of Stiff Clay in the Presence of Free Water ................................................ 75 3-3-9 Response of Stiff Clay with No Free Water ................................................................ 84 3-3-10 Modified p-y Formulation for Stiff Clay with No Free Water .................................. 88 3-3-11 Other Recommendations for p-y Curves in Clays ..................................................... 89 3-4 p-y Curves for Cohesionless Soils ...................................................................................... 89 3-4-1 Description of p-y Curves in Sands ............................................................................. 89 3-4-2 Reese, et al. (1974) Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Sand ............................ 94 3-4-3 API RP 2A Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Sand ....................................... 100 3-4-4 Other Recommendations for p-y Curves in Sand ...................................................... 106 3-5 p-y Curves for Liquefied Soils.......................................................................................... 107 3-5-1 Response of Piles in Liquefied Sand ......................................................................... 107 3-5-2 Method of Rollins et al. (2005a) ............................................................................... 108 3-5-3 Simplified Hybrid p-y Model .................................................................................... 110 3-5-4 Modeling of Lateral Spread....................................................................................... 116 3-6 p-y Curves for Loess Soils ................................................................................................ 116 3-6-1 Background ............................................................................................................... 116 3-6-2 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Loess ......................................................... 118 3-7 p-y Curves for Cemented Soils with Both Cohesion and Friction ................................... 125 3-7-1 Background ............................................................................................................... 125 3-7-2 Recommendations for Computing p-y Curves .......................................................... 126 3-7-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Soils with Both Cohesion and Internal Friction ................................................................................................................................ 128 3-7-4 Discussion ................................................................................................................. 131 3-8 p-y Curves for Rock .......................................................................................................... 132 3-8-1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 132 3-8-2 Descriptions of Two Field Experiments.................................................................... 133 3-8-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Vuggy Limestone ...................................... 138 3-8-4 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Weak Rock ................................................ 138 3-8-5 Case Histories for Drilled Shafts in Weak Rock ....................................................... 141 3-9 p-y Curves for Massive Rock ........................................................................................... 146 3-9-1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 146 3-9-2 Shearing Properties of Massive Rock ....................................................................... 146 3-9-3 Determination of Rock Mass Modulus ..................................................................... 148 3-9-4 Determination of pus Near the Ground Surface ......................................................... 150 3-9-5 Determination of pud at Great Depth ......................................................................... 152 3-9-6 Determination of Initial Tangent Stiffness of p-y Curve Ki ...................................... 153 3-9-7 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Massive Rock ............................................ 153 3-10 p-y Curves in Piedmont Residual Soils .......................................................................... 154 3-11 Response of Layered Soils ............................................................................................. 155 3-11-1 Layering Correction Method of Georgiadis ............................................................ 156 3-11-2 Example p-y Curves in Layered Soils ..................................................................... 158 3-11-3 Modified Equations Using Equivalent Depth ......................................................... 163 3-12 Modifications to p-y Curves for Pile Batter and Ground Slope ..................................... 166 iv 3-12-1 Piles in Sloping Ground .......................................................................................... 166 3-12-2 Effect of Batter on p-y Curves in Clay and Sand .................................................... 169 3-12-3 Modeling of Piles in Short Slopes ........................................................................... 170 3-13 Shearing Force Acting at Pile Tip .................................................................................. 171 Chapter 4 Special Analyses ........................................................................................................ 172 4-1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 172 4-2 Computation of Top Deflection versus Pile Length ......................................................... 172 4-3 Analysis of Piles Loaded by Soil Movements .................................................................. 175 4-4 Analysis of Pile Buckling ................................................................................................. 176 4-4-1 Procedure for Analysis of Pile Buckling ................................................................... 176 4-4-2 Example of An Incorrect Pile Buckling Analysis ..................................................... 178 4-4-3 Evaluation of Pile Buckling Capacity ....................................................................... 179 4-5 Pushover Analysis of Piles ............................................................................................... 181 4-5-1 Procedure for Pushover Analysis .............................................................................. 181 4-5-2 Example of Pushover Analysis ................................................................................. 182 4-5-3 Evaluation of Pushover Analysis .............................................................................. 183 4-6 Computation of Foundation Stiffness Matrix ................................................................... 183 Chapter 5 Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity....................... 188 5-1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 188 5-1-1 Application ................................................................................................................ 188 5-1-2 Assumptions .............................................................................................................. 188 5-1-3 Stress-Strain Curves for Concrete and Steel ............................................................. 189 5-1-4 Cross Sectional Shape Types .................................................................................... 191 5-2 Beam Theory .................................................................................................................... 191 5-2-1 Flexural Behavior ...................................................................................................... 191 5-2-2 Axial Structural Capacity .......................................................................................... 194 5-3 Validation of Method........................................................................................................ 195 5-3-1 Analysis of Concrete Sections................................................................................... 195 5-3-2 Analysis of Steel Pipe Piles....................................................................................... 206 5-3-3 Analysis of Prestressed-Concrete Piles ..................................................................... 208 5-4 Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 211 5-5 Reference Information ...................................................................................................... 212 5-5-1 Standard Concrete Reinforcing Steel Sizes ............................................................... 212 5-5-2 Prestressing Strand Types and Sizes ......................................................................... 213 5-5-3 Steel H-Piles .............................................................................................................. 214 Chapter 6 Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope ................................................................... 216 6-1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 216 6-2 Proposed Methods ............................................................................................................ 216 6-3 Review of Some Previous Applications ........................................................................... 218 6-4 Analytical Procedure ........................................................................................................ 218 6-5 Alternative Method of Analysis ....................................................................................... 221 6-6 Case Studies and Example Computation .......................................................................... 222 6-6-1 Case Studies .............................................................................................................. 222 6-6-2 Example Computation ............................................................................................... 222 v 6-6-3 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 225 References ................................................................................................................................... 226 Name Index ................................................................................................................................. 234 vi List of Figures Figure 1-1 Example of Modeling a Bridge Foundation ............................................................... 18 Figure 1-2 Three-dimensional Soil-Pile Interaction .................................................................... 20 Figure 1-3 Coefficients of Pile-head Stiffness Matrix ................................................................. 20 Figure 2-1 Models of Piles Under Lateral Loading, (a) 3-Dimensional Finite Element Mesh, and (b) Cross-section of 3-D Finite Element Mesh, (c) Brom’s Model, (d) MFAD Model ..................................................................................................... 27 Figure 2-2 Model of a Pile Under Lateral Loading and p-y Curves ............................................ 29 Figure 2-3 Distribution of Stresses Acting on a Pile, (a) Before Lateral Deflection and (b) After Lateral Deflection y ......................................................................................... 30 Figure 2-4 Variation of Shear Stresses in Pile and Soil for Displaced Pile ................................. 31 Figure 2-5 Illustration of General Procedure for Selecting a Pile to Sustain a Given Set of Loads ........................................................................................................................ 33 Figure 2-6 Analysis of Pile Buckling........................................................................................... 34 Figure 2-7 Solving for Critical Pile Length ................................................................................. 35 Figure 2-8 Simplified Method of Analyzing a Pile for an Offshore Platform ............................. 36 Figure 2-9 Analysis of a Breasting Dolphin ................................................................................ 38 Figure 2-10 Loading On a Single Shaft Supporting a Bridge Deck ............................................ 39 Figure 2-11 Foundation Options for an Overhead Sign Structure ............................................... 40 Figure 2-12 Use of Piles to Stabilize a Slope Failure .................................................................. 41 Figure 2-13 Anchor Pile for a Flexible Bulkhead ........................................................................ 42 Figure 2-14 Element of Beam-Column (after Hetenyi, 1946) ..................................................... 43 Figure 2-15 Sign Conventions ..................................................................................................... 45 Figure 2-16 Form of Results Obtained for a Complete Solution ................................................. 46 Figure 2-17 Boundary Conditions at Top of Pile......................................................................... 47 Figure 2-18 Values of Coefficients A1, B1, C1, and D1 ................................................................ 50 Figure 2-19 Representation of deflected pile ............................................................................... 53 Figure 2-20 Case 1 of Boundary Conditions ............................................................................... 54 Figure 2-21 Case 2 of Boundary Conditions ............................................................................... 55 Figure 2-22 Case 3 of Boundary Conditions ............................................................................... 56 Figure 2-23 Case 4 of Boundary Conditions ............................................................................... 57 Figure 2-24 Case 5 of Boundary Conditions ............................................................................... 57 Figure 3-1 Conceptual p-y Curves ............................................................................................... 61 vii Figure 3-2 p-y Curves from Static Load Test on 24-inch Diameter Pile (Reese, et al. 1975) ..... 64 Figure 3-3 p-y Curves from Cyclic Load Test on 24-inch Diameter Pile (Reese, et al. 1975) ......................................................................................................................... 65 Figure 3-4 Plot of Ratio of Initial Modulus to Undrained Shear Strength for Unconfinedcompression Tests on Clay ....................................................................................... 67 Figure 3-5 Variation of Initial Modulus with Depth .................................................................... 68 Figure 3-6 Assumed Passive Wedge Failure in Clay Soils, (a) Shape of Wedge, (b) Forces Acting on Wedge ...................................................................................................... 69 Figure 3-7 Measured Profiles of Ground Surface Heave Near Piles Due to Static Loading, (a) Ground Surface Heave at Maximum Load, (b) Residual Ground Surface Heave ........................................................................................................................ 70 Figure 3-8 Ultimate Lateral Resistance for Clay Soils ................................................................ 72 Figure 3-9 Assumed Mode of Soil Failure Around Pile in Clay, (a) Section Through Pile, (b) Mohr-Coulomb Diagram, (c) Forces Acting on Section of Pile ......................... 73 Figure 3-10 Values of Ac and As................................................................................................... 74 Figure 3-11 Development of Scour Around Pile in Clay During Cyclic Loading, (a) Profile View, (b) Photograph of Turbulence Causing Erosion During Lateral Load Test .................................................................................................................. 76 Figure 3-12 p-y Curves in Soft Clay,(a) Static Loading, (b) Cyclic Loading .............................. 82 Figure 3-13 Example p-y Curves in Soft Clay Showing Effect of J ............................................ 83 Figure 3-14 Shear Strength Profile Used for Example p-y Curves for Soft Clay ........................ 85 Figure 3-15 Example p-y Curves for Soft Clay with the Presence of Free Water ....................... 85 Figure 3-16 Annular Gapping Developed Around Pile After Cyclic Loading ............................ 87 Figure 3-17 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Static Loading in Stiff Clay with Free Water ........................................................................................................................ 88 Figure 3-18 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Cyclic Loading of Stiff Clay with Free Water ........................................................................................................................ 91 Figure 3-19 Example Shear Strength Profile for p-y Curves for Stiff Clay with No Free Water ........................................................................................................................ 93 Figure 3-20 Example p-y Curves for Stiff Clay in Presence of Free Water for Cyclic Loading ..................................................................................................................... 93 Figure 3-21 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curve for Static Loading in Stiff Clay without Free Water ................................................................................................................ 95 Figure 3-22 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Cyclic Loading in Stiff Clay with No Free Water ................................................................................................................ 96 Figure 3-23 Ratio of Expansion versus Number of Cycles of Loading for Stiff Clay without Free Water ................................................................................................... 97 viii Figure 3-24 Example p-y Curves for Stiff Clay with No Free Water, Cyclic Loading .............. 98 Figure 3-25 Geometry Assumed for Passive Wedge Failure for Pile in Sand ........................... 101 Figure 3-26 Assumed Mode of Soil Failure by Lateral Flow Around Pile in Sand, (a) Section Though Pile, (b) Mohr-Coulomb Diagram ................................................ 103 Figure 3-27 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Static and Cyclic Loading in Sand ........... 105 Figure 3-28 Values of Coefficients Ac and As for Cohesionless Soils ................................... 106 Figure 3-29 Values of Coefficients Bc and Bs for Cohesionless Soils ....................................... 107 Figure 3-31 Example p-y Curves for Sand Below the Water Table, Static Loading ................. 110 Figure 3-32 Coefficients C1, C2, and C3 versus Angle of Internal Friction ............................... 112 Figure 3-33 Value of k for API Sand Procedure ........................................................................ 113 Figure 3-34 Value of k versus Friction Angle for Fine Sand Used in LPile .............................. 114 Figure 3-35 Example p-y Curves for API Sand Criteria ............................................................ 116 Figure 3-36 Example p-y Curve in Liquefied Sand ................................................................... 118 Figure 3-37 Recommended Method for Computing Residual Shear Strength of Liquefied Soil for Use in Hybrid p-y Model ........................................................................... 122 Figure 3-38 Factor 50 as Function of SPT Blowcount .............................................................. 123 Figure 3-39 Possible Intersection Patterns of Residual and Dilative p-y Curves in Hybrid p-y Model................................................................................................................ 124 Figure 3-40 Example of Non-intersecting Curves ..................................................................... 124 Figure 3-41 Example of Curves with One Intersection of Dilative and Residual Curves ......... 125 Figure 3-42 Example of Curve with One Intersection of Dilative Curve and Residual Plateau .................................................................................................................... 125 Figure 3-43 Example of Curve with Two Intersection Points ................................................... 126 Figure 3-37 Idealized Tip Resistance Profile from CPT Testing Used for Analyses. ............... 128 Figure 3-38. Generic p-y curve for Drilled Shafts in Loess Soils .............................................. 129 Figure 3-39 Variation of Modulus Ratio with Normalized Lateral Displacement .................... 132 Figure 3-40 p-y Curves for the 30-inch Diameter Shafts ........................................................... 133 Figure 3-41 p-y Curves and Secant Modulus for the 42-inch Diameter Shafts. ........................ 133 Figure 3-42 Cyclic Degradation of p-y Curves for 30-inch Shafts ............................................ 134 Figure 3-43 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for c- Soil ..................................................... 136 Figure 3-44 Representative Values of k for c- Soil.................................................................. 139 Figure 3-46 p-y Curves for Cemented c- Soil .......................................................................... 142 Figure 3-47 Initial Moduli of Rock Measured by Pressuremeter for San Francisco Load Test ......................................................................................................................... 145 ix Figure 3-48 Modulus Reduction Ratio versus RQD (Bienawski, 1984) ................................... 146 Figure 3-49 Engineering Properties for Intact Rocks (after Deere, 1968; Peck, 1976; and Horvath and Kenney, 1979) ................................................................................... 147 Figure 3-50 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curve in Strong Rock ................................................ 148 Figure 3-51 Sketch of p-y Curve for Weak Rock (after Reese, 1997) ....................................... 149 Figure 3-52 Comparison of Experimental and Computed Values of Pile-Head Deflection, Islamorada Test (after Reese, 1997) ....................................................................... 152 Figure 3-53 Computed Curves of Lateral Deflection and Bending Moment versus Depth, Islamorada Test, Lateral Load of 334 kN (after Reese, 1997) ............................... 153 Figure 3-54 Comparison of Experimental and Computed Values of Pile-Head Deflection for Different Values of EI, San Francisco Test ...................................................... 154 Figure 3-55 Values of EI for three methods, San Francisco test ............................................... 155 Figure 3-56 Comparison of Experimental and Computed Values of Maximum Bending Moments for Different Values of EI, San Francisco Test ...................................... 155 Figure 3-57 p-y Curve in Massive Rock .................................................................................... 156 Figure 3-58 Equation for Estimating Modulus Reduction Ratio from Geological Strength Index ....................................................................................................................... 159 Figure 3-59 Poisson’s Ratio as Function of Stress Wave Velocity Ratio .................................. 160 Figure 3-60 Model of Passive Wedge for Drilled Shafts in Rock ............................................. 161 Figure 3-61 Degradation Plot for Es .......................................................................................... 165 Figure 3-62 p-y Curve for Piedmont Residual Soil.................................................................... 165 Figure 3-63 Illustration of Equivalent Depths in a Multi-layer Soil Profile .............................. 167 Figure 3-64 Soil Profile for Example of Layered Soils ............................................................. 169 Figure 3-65 Equivalent Depths of Soil Layers Used for Computing p-y Curves ...................... 169 Figure 3-66 Example p-y Curves for Layered Soil .................................................................... 170 Figure 3-67 Pile in Sloping Ground and Battered Pile .............................................................. 177 Figure 3-68 Soil Resistance Ratios for p-y Curves for Battered Piles from Experiment from Kubo (1964) and Awoshika and Reese (1971) .............................................. 180 Figure 4-1 Pile and Soil Profile for Example Problem .............................................................. 183 Figure 4-2 Variation of Top Deflection versus Depth for Example Problem ............................ 183 Figure 4-3 Pile-head Load versus Deflection for Example........................................................ 184 Figure 4-4 Top Deflection versus Pile Length for Example ...................................................... 184 Figure 4-5 Evaluation of Soil Modulus from p-y Curve Displaced by Soil Movement ............ 186 Figure 4-6 Examples of Pile Buckling Curves for Different Shear Force Values ..................... 188 Figure 4-7 Examples of Correct and Incorrect Pile Buckling Analyses .................................... 189 x Figure 4-8 Typical Results from Pile Buckling Analysis .......................................................... 190 Figure 4-9 Pile Buckling Results Showing a and b ................................................................... 190 Figure 4-10 LPile Dialog for Controls for Pushover Analysis .................................................. 191 Figure 4-11 Pile-head Shear Force versus Displacement from Pushover Analysis ................... 192 Figure 4-12 Maximum Moment Developed in Pile versus Displacement from Pushover Analysis .................................................................................................................. 193 Figure 4-13 Example of Stiffness Matrix of Foundation ........................................................... 194 Figure 4-14 Coefficients of Pile-head Stiffness Matrix ............................................................. 195 Figure 5-1 Stress-Strain Relationship for Concrete Used by LPile ........................................... 199 Figure 5-2 Stress-Strain Relationship for Reinforcing Steel Used by LPile.............................. 200 Figure 5-3 Element of Beam Subjected to Pure Bending .......................................................... 202 Figure 5-4 Validation Problem for Mechanistic Analysis of Rectangular Section.................... 206 Figure 5-5 Free Body Diagram Used for Computing Nominal Moment Capacity of Reinforced Concrete Section .................................................................................. 213 Figure 5-6 Bending Moment versus Curvature.......................................................................... 214 Figure 5-7 Bending Moment versus Bending Stiffness ............................................................. 215 Figure 5-8 Interaction Diagram for Nominal Moment Capacity ............................................... 215 Figure 5-9 Example Pipe Section for Computation of Plastic Moment Capacity ..................... 216 Figure 5-10 Moment versus Curvature of Example Pipe Section ............................................. 216 Figure 5-11 Elasto-plastic Stress Distribution Computed by LPile ........................................... 218 Figure 5-12 Stress-Strain Curves of Prestressing Strands Recommended by PCI Design Handbook, 5th Edition............................................................................................. 219 Figure 5-13 Sections for Prestressed Concrete Piles Modeled in LPile .................................... 221 Figure 6-1 Scheme for Installing a Row of Piles in a Slope Subject to Sliding ........................ 227 Figure 6-2 Scheme for Stabilizing Piles with Grade Beam and Anchor Pile Group ................. 227 Figure 6-3 Forces from Soil Acting Against a Pile in a Sliding Slope, (a) Pile, Slope, and Slip Surface Geometry, (b) Distribution of Mobilized Forces, (c) Free-body Diagram of Pile Below the Slip Surface................................................................. 229 Figure 6-4 Influence of Stabilizing Pile on Factor of Safety Against Sliding ........................... 230 Figure 6-5 Matching of Computed and Assumed Values of hp ................................................. 231 Figure 6-6 Soil Conditions for Analysis of Slope for Low Water ............................................. 233 Figure 6-7 Preliminary Design of Stabilizing Piles ................................................................... 234 Figure 6-8 Load Distribution from Stabilizing Piles for Slope Stability Analysis .................... 235 xi List of Tables Table 3-1 Terzaghi’s Recommendations for Soil Modulus for Laterally Loaded Piles in Stiff Clay (no longer recommended) ........................................................................ 79 Table 3-2 Representative Values of 50 for Soft to Stiff Clays .................................................... 81 Table 3-3 Representative Values of k for Stiff Clays................................................................... 89 Table 3-4 Representative Values of 50 for Stiff to Hard Clays ................................................... 89 Table 3-5 k Values Recommended by Terzaghi for Laterally Loaded Piles in Sand ............... 100 Table 3-6 Representative Values of k for Fine Sand Below the Water Table for Static and Cyclic Loading ....................................................................................................... 108 Table 3-7 Representative Values of k for Fine Sand Above Water Table for Static and Cyclic Loading ....................................................................................................... 108 Table 3-8 Results of Grout Plug Tests by Schmertmann (1977) ............................................... 144 Table 3-9 Values of Compressive Strength at San Francisco .................................................... 146 Table 3-10 Values of Material Index mi for Intact Rock, by Rock Group (from Hoek, 2001) ....................................................................................................................... 158 Table 3-11 Typical Properties for Rock Masses (from Hoek, 2001) ......................................... 160 Table 3-12 Tablulated Values of As as Function of z/b ............................................................ 171 Table 3-13 Computed Values of pu and F1 for the Sand in Figure 3-64 as Function of Depth ...................................................................................................................... 172 Table 3-14 Equivalent Depths of Tops of Soil Layers Computed by LPile .............................. 172 Table 3-15 Equivalent Depths of Example p-y Curves Computed by Hand and by LPile ........ 173 Table 5-1 LPile Output for Rectangular Concrete Section ........................................................ 207 Table 5-2 Comparison of Results from Hand Computation versus Computer Solution............ 214 xii Chapter 1 Introduction 1-1 Compatible Designs The program LPile provides the capability to analyze individual piles for a variety of applications in which lateral loading is applied. The analysis is based on solution of a differential equation describing the behavior of a beam-column with nonlinear support. The solution obtained ensures that the computed deformations and stresses in the foundation and supporting soil are compatible and consistent. Analyses of this type have been in use in the practice of civil engineering since the 1950’s and the analytical procedures that are used in LPile are widely accepted. The one goal of foundation engineering is to predict how a foundation will deform and deflect in response to loading. In advanced analyses, the analysis of the foundation performance can be combined with that those for the superstructure to provide a global solution in which both equilibrium of forces and moments and compatibility of displacements and rotations is achieved. Analyses of this type are possible because of the power of computer software for analysis and computer graphics. Calibration and verification of the analyses is possible because of the availability of sophisticated instrumentation and data acquisition systems for observing the behavior of structural systems. Some problems can be solved only by using the concepts of soil-structure interaction. Presented herein are analyses for isolated piles that achieve the pile response while simultaneously satisfying the appropriate nonlinear response of the soil. In these analyses, the pile is treated as a beam-column and the soil is modelled with nonlinear Winkler-spring mechanisms. These mechanisms can accurately predict the response of the soil and provide a means of obtaining solutions to a number of practical problems. 1-2 Principles of Design 1-2-1 Introduction The design of a pile foundation to sustain a combination of lateral and axial loading requires the designing engineer to consider factors involving both performance of the foundation to support loading and the costs and methods of construction for different types of foundations. Presentation of complete designs as examples and a discussion many practical details related to construction of piles is outside the scope for this manual. The discussion of the analytical methods presented herein address two aspects of design that are helpful to the user. These aspects of design are computation of the loading at which a particular pile will fail as a structural member and identification of the level of loading that will cause an unacceptable lateral deflection. The analysis made using LPile includes computation of deflections, bending moments, and shear forces developed along the length of a pile under 1 Chapter 1 – Introduction loading. Additional considerations that are useful are computation of the minimum required length of a pile foundation, computation of pile-head stiffness relationships, and the evaluation of the buckling capacity of a pile that extends above the ground line. 1-2-2 Modelling of Nonlinear Response of Soil In one sense, the design of a pile under lateral loading is no different that the design of any foundation. First, one needs to determine the loading of the foundation that will cause failure and then apply a global factor of safety or alternatively to apply load and resistance factors to set the allowable loading capacity of the foundation. What is different for analysis of lateral loading is that the limit states for evaluating a design cannot be found by solving the equations of static equilibrium alone. Instead, the lateral capacity of the foundation is found by first solving a differential equation governing the pile’s behavior and then evaluating the results of the solution. Furthermore, as noted below, use of a closed-form solution of the differential equation, as with the use a constant modulus of subgrade reaction, is inappropriate in the vast majority of cases. To illustrate the nonlinear response of soil to lateral loading of a pile, curves of response of soil obtained from the results of a full-scale lateral load test of a steel-pipe pile are presented in Chapter 2. This test pile was instrumented for measurement of bending moment and was driven into overconsolidated clay with free water present above the ground surface. The results of static load testing definitely show that the soil resistance is nonlinear with pile deflection and increases with depth. With cyclic loading, frequently encountered in practice, the nonlinearity in load-deflection response is greatly increased. Thus, if a linear analysis shows a tolerable level of stress in a pile and of deflection, an increase in loading could cause a failure by collapse or by excessive deflection. Therefore, a basic principle of compatible design is that nonlinear response of the soil to lateral loading must be considered. 1-2-3 Limit States In many instances, failure of a pile is initiated by a bending moment that would cause the development of a plastic hinge. However, in other instances the failure could be due to excessive deflection, or, in a small fraction of cases, by shear failure of the pile. Therefore, pile design is based on a decision of what constitutes a limit state for structural failure or excessive deflection. Then, computations are made to determine if the loading considered exceeds the limit states. A global factor of safety is normally employed to find the allowable loading, the service load level, or the working load level. Alternatively, an approach using load and resistance factors may be employed. However, analyses employed in applying load and resistance factors is implemented herein by using upperbound and lower-bound values of the important parameters. 1-2-4 Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Collect all relevant data, including the soil profile, soil properties, magnitude and type of loading, and performance requirements for the structure. 2. Select a pile type and size for analysis. 3. Compute curves of nominal bending moment capacity as a function of axial thrust load and curvature; compute the corresponding values of nonlinear bending stiffness. 2 Chapter1 – Introduction 4. Select p-y curve types for the analysis, along with average, upper bound, and lower bound values of input variables. 5. Make a series of solutions, starting with a small load and increasing the load in increments, with consideration of the manner the pile is fastened to the superstructure. 6. Obtain curves showing maximum moment in the pile and lateral pile-head deflection versus lateral shear loading and curves of lateral deflection, bending moment, and shear force versus depth along the pile. 7. Change the pile dimensions or pile type, if necessary and repeat the analyses until a range of suitable pile types and sizes have been identified. 8. Identify the pile type and size for which the global factor of safety is adequate and the most efficient cost of the pile and construction is estimate. 9. Compute behavior of pile under working loads. Few of the examples presented in this manual need to follow all steps indicated above. However, in most cases, the examples do show the curves that are indicated in Step 6. 1-2-5 Suggestions for the Designing Engineer As will be explained in some detail, there are five sets of boundary conditions that can be employed; examples will be shown for the use of these different boundary conditions. However, the manner in which the top of the pile is fastened to the pile cap or to the superstructure has a significant influence on deflections and bending moments that are computed. The engineer may be required to perform an analysis of the superstructure, or request that one be made, in order to ensure that the boundary conditions at the top of the pile are satisfied as well as possible. With regard to boundary conditions at the pile head, it is important to note the versatility of LPile. For example, piles that are driven with an accidental batter or an accidental eccentricity can be easily analyzed. It is merely necessary to define the appropriate conditions for the analysis. As noted earlier, selection of upper and lower bound values of soil properties is a practical procedure. Parametric solutions are easily done and relatively inexpensive and such solutions are recommended. With the range of maximum values of bending moment that result from the parametric studies, for example, the insight and judgment of the engineer can be improved and a design can probably be selected that is both safe and economical. Alternatively, one may perform a first-order, second moment reliability analysis to evaluate variance in performance for selected random variables. For further guidance on this topic, the reader is referred to the textbook by Baecher and Christian (2003). If the axial load is small or negligible, it is recommended to make solutions with piles of various lengths. In the case of short piles, the mobilization shear force at the bottom of the pile can be defined along with the soil properties. In most cases, the installation of a few extra feet of pile length will add little cost to the project and, if there is doubt, a pile with a few feet of additional length could possibly prevent a failure due to excessive deflection. If the base of the pile is founded in rock, available evidence shows that often only a short socket will be necessary to anchor the bottom of the pile. In all cases, the designer must assure that the pile has adequate bending stiffness over its full length. 3 Chapter 1 – Introduction A useful activity for a designer is to use LPile to analyze piles for which experimental results are available. It is, of course, necessary to know the appropriate details from the load tests; pile geometry and bending stiffness, stratigraphy and soil properties, magnitude and point of application of loading, and the type of loading (either static or cyclic). Many such experiments have been run in the past. Comparison of the results from analysis and from experiment can yield valuable information and insight to the designer. Some comparisons are provided in this document, but those made by the user could be more site-specific and more valuable. In some instances, the parametric studies may reveal that a field test is indicated. Such a case occurs when a large project is planned and when the expected savings from an improved design exceeds the cost of the testing. Savings in construction costs may be derived either by proving a more economical foundation design is feasible, by permitting use of a lower factor of safety or, in the case of a load and resistance factor design, use of an increased strength reduction factor for the soil resistance. There are two types of field tests. In one instance, the pile may be fully instrumented so that experimental p-y curves are obtained. The second type of test requires no internal instrumentation in the pile but only the pile-head settlement, deflection, and rotation will be found as a function of applied load. LPile can be used to analyze the experiment and the soil properties can be adjusted until agreement is reached between the results from the computer and those from the experiment. The adjusted soil properties can be used in the design of the production piles. In performing the experiment, no attempt should be made to maintain the conditions at the pile head identical to those in the design. Such a procedure could be virtually impossible. Rather, the pile and the experiment should be designed so that the maximum amount of deflection is achieved. Thus, the greatest amount of information can be obtained on soil response. The nature of the loading during testing; whether static, cyclic, or otherwise; should be consistent for both the experimental pile and the production piles. The two types of problems concerning the performance of pile groups of piles are computation of the distribution of loading from the pile cap to a widely spaced group of piles and the computation of the behavior of spaced-closely piles. The first of these problems involves the solutions of the equations of structural mechanics that govern the distribution of moments and forces to the piles in the pile group (Hrennikoff, 1950; Awoshika and Reese, 1971; Akinmusuru, 1980). For all but the most simple group geometries, solution of this problem requires the use of a computer program developed for its solution. The second of the two problems is more difficult because less data from full-scale experiments is available (and is often difficult to obtain). Some full-scale experiments have been performed in recent years and have been reported (Brown, et al., 1987; Brown et al., 1988). These and additional references are of assistance to the designer (Bogard and Matlock, 1983; Focht and Koch, 1973; O’Neill, et al., 1977). The technical literature includes significant findings from time to time on piles under lateral loading. Ensoft will take advantage of the new information as it becomes available and verified by loading testing and will issue new versions of LPile when appropriate. However, the material that follows in the remaining sections of this document shows that there is an 4 Chapter1 – Introduction opportunity for rewarding research on the topic of this document, and the user is urged to stay current with the literature as much as possible. 1-3 Modeling a Pile Foundation 1-3-1 Introduction As a problem in foundation engineering, the analysis of a pile under combined axial and lateral loading is complicated by the fact that the mobilized soil reaction varies in proportion to the pile movement, and the pile movement, on the other hand, is dependent on the soil response. This is the basic problem of soil-structure interaction. The question about how to simulate the behavior of the pile in the analysis arises when the foundation engineer attempts to use boundary conditions for the connection between the structure and the foundation. Ideally, a program can be developed by combining the structure, piles, and soils into a single model. However, special purpose programs that permit development of a global model are currently unavailable. Instead, the approach described below is commonly used for solving for the nonlinear response of the pile foundation so that equilibrium and compatibility can be achieved with the superstructure. The use of models for the analysis of the behavior of a bridge is shown in Figure 1-1(a). A simple, two-span bridge is shown with spans in the order of 30 m and with piles supporting the abutments and the central span. The girders and columns are modeled by lumped masses and the foundations are modeled by nonlinear springs, as shown in Figure 1-1(b). If the loading is threedimensional, the pile head at the central span will undergo three translations and three rotations. A simple matrix-formulation for the pile foundation is shown in Figure 1-1(c), assuming twodimensional loading, along with a set of mechanisms for the modeling of the foundation. Three springs are shown as symbols of the response of the pile head to loading; one for axial load, one for lateral load, and one for moment. The assumption is made in analysis that the nonlinear curve for axial loading is not greatly influenced by lateral loading (shear) and moment. This assumption is not strictly true because lateral loading can cause gapping in overconsolidated clay at the top of the pile with a consequent loss of load transfer in skin friction along the upper portion of the pile. However, in such a case, the soil near the ground surface could be ignored above the first point of zero lateral deflection. The practical result of such a practice in most cases is that the curve of axial load versus settlement and the stiffness coefficient K11 are negligibly affected. The curves representing the response to shear and moment at the top of the pile are certainly multidimensional and unavoidably so. Figure 1-1(c) shows a curve and identifies one of the stiffness terms K32. A single-valued curve is shown only because a given ratio of moment M1 and shear V1 was selected in computing the curve. Therefore, because such a ratio would be unknown in the general case, iteration is required between the solutions for the superstructure and the foundation. The conventional procedure is to select values for shear and moment at the pile head and to compute the initial stiffness terms so that the solution of the superstructure can proceed for the most critical cases of loading. With revised values of shear and moment at the pile head, the model for the pile can be resolved and revised terms for the stiffnesses can be used in a new solution of the model for the superstructure. The procedure could be performed automatically if a computer program capable of analyzing the global model were available but the use of 5 Chapter 1 – Introduction independent models allows the designer to exercise engineering judgment in achieving compatibility and equilibrium for the entire system for a given case of loading. a. Elevation View Lumped masses Foundation springs b. Analytical Model K33 K22 Moment M K11 K33 Rotation K11 0 0 K11 x P 0 0 0 0 Q x 0 y V K K 22K K23H 22 23 0 K 32 K33 My K 32 K 33 M c. Stiffness Matrix Figure 1-1 Example of Modeling a Bridge Foundation 6 Chapter1 – Introduction The stiffness K11 is the stiffness of the axial load-settlement curve for the axial load P. This stiffness is obtained either from load test results or from a numerical analysis using an axial capacity analysis program like Shaft or APile from Ensoft, Inc. 1-3-2 Example Model of Individual Pile with Axial and Lateral Loading An interesting presentation of the forces that resist the displacements of an individual pile is shown in Figure 1-2 (Bryant, 1977). Figure 1-2(a) shows a single pile beneath a cap along with the three-dimensional displacements and rotations. The assumption is made that the top of the pile is fixed or partially fixed into the cap and that biaxial bending and torsion reactions will develop because of the three-dimensional translation and rotation of the cap. The reactions of the soil along the pile are shown in Figure 1-2(b), and the load-transfer curves are shown in Figure 1-2(c). The argument given earlier about the curve for axial displacement being single-value pertains as well to the curve for axial torque. However, the curve for lateral deflection is certainly a function of the shear forces and moments that cause such deflection. When computing lateral deflection, a complication may arise because the loading and deflection may not be in a two-dimensional plane. The recommendations that have been made for correlating the lateral resistance with pile geometry and soil properties all depend on the results of loading in a twodimensional plane. q y Axial Py x u Px My Mx Axial Pile Displacement, u z Mz Pz p Axial Soil Reaction, q Lateral y Torsional Pile Displacement, Lateral Soil Reaction, p t Lateral Pile Displacement, y Torsional Soil Reaction, t (a) Three-dimensional pile displacements (b) Pile reactions 7 Torsional (c) Nonlinear load-transfer curves Chapter 1 – Introduction Figure 1-2 Three-dimensional Soil-Pile Interaction 1-3-3 Computation of Foundation Stiffness Stiffness matrices are often used to model foundations in structural analyses and LPile provides an option for evaluating the lateral stiffness of a deep foundation. This feature in LPile allows the user to solve for coefficients, as illustrated by the sketches shown in Figure 1-3, of pile-head movements and rotations as functions of incremental loadings. The program divides the loads specified at the pile head into increments and then computes the pile head response for each individual loading. The deflection of the pile head is computed for each lateral-load increment with the rotation at the pile head being restrained to zero. Next, the rotation of the pile head is computed for each bending-moment increment with the lateral deflection at the pile head being restrained to zero. The user can thus define the stiffness matrix directly based on the relationship between computed deformation and applied load. For instance, the stiffness coefficient K33, shown in Figure 1-1(c), can be obtained by dividing the applied moment M by the computed rotation θ at the pile top. P P M −M −V V 0 0 0 0 Stiffnesses K22 and K23 are computed using the shear-rotation pile-head condition, for which the user enters the lateral load V at the pile head. LPile computes pile-head deflection and reaction moment −M at the pile head using zero slope at the pile head (pile head rotation = 0). Stiffnesses K32 and K33 are computed using the displacement-moment pile-head condition, for which the user enters the moment M at the pile head. LPile computes the lateral reaction force, −H, and pile-head rotation using zero deflection at the pile head ( = 0). K22 = V/ and K32 = –M/ . K23 = –V/ and K33 = M/ . Figure 1-3 Coefficients of Pile-head Stiffness Matrix 8 Chapter1 – Introduction Most analytical methods in structural mechanics can employ either the stiffness matrix or the flexibility matrix to define the support condition at the pile head. If the user prefers to use the stiffness matrix in the structural model, Figure 1-3 illustrates basic procedures used to compute a stiffness matrix. The initial coefficients for the stiffness matrix may be defined based on the magnitude of the service load. The user may need to make several iterations before achieving acceptable agreement. 1-3-4 Concluding Comments The correct modeling of the problem of the single pile to respond to axial and lateral loading is challenging and complex, and the modeling of a group of piles is even more complex. However, in spite of the fact that research is continuing, the following chapters will demonstrate that usable solutions are at hand. New developments in computer technology allow a complete solution to be readily developed, including automatic generation of the nonlinear responses of the soil around a pile and iteration to achieve force equilibrium and compatibility. 1-4 Organization of Technical Manual Chapters 2, 3, and 4 provide the user with background information on soil-pile interaction for lateral loading and present the equations that are solved when obtaining a solution for the beam-column problem when including the effects of the nonlinear response of the soil. In addition, information on the verification of the validity of a particular set of output is given. The user is urged to read carefully these latter two sections. Output from the computer should be viewed with caution unless verified, and the user’s selection of the appropriate soil response (p-y curves) is the most critical aspect of most computations. Not all engineers will have a computer program available that can be used to predict the level of bending moment in a reinforced-concrete section at which a plastic hinge will develop, while taking into account the influence of axial thrust loading. Chapter 5 of this manual describes features of LPile that are provided for this purpose. LPile can compute the flexural rigidity of the pile sections as a function of the developed bending moments. Finally, Chapter 6 includes the development of a solution that is designed to give the user some guidance in the use of piles to stabilize a slope. While no special coding is necessary for the purpose indicated, the number of steps in the solution is such that a separate section is desirable rather than including this example with those in the User’s Manual for LPile. 9 Chapter 1 – Introduction (This page was deliberately left blank) 10 Chapter 2 Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading 2-1 Introduction Many pile-supported structures will be subjected to horizontal loads during their functional lifetime. If the loads are relatively small, a design can be made by building code provisions that list allowable loads for vertical piles as a function of pile diameter and properties of the soil. However, if the load per pile is large, the piles are frequently installed at a batter. The analyst may assume that the horizontal load on the structure is resisted by components of the axial loads on the battered piles. The implicit assumption in the procedure is that the piles do not deflect laterally which, of course, is not true. Rational methods for the analysis of single piles under lateral load, where the piles are vertical or battered, will be discussed herein, and methods are given for investigating a wide variety of parameters. The problem of the analysis of a group of piles is discussed in another publication. As a foundation problem, the analysis of a pile under lateral loading is complicated because the soil reaction (resistance) at any point along a pile is a function of pile deflection. The pile deflection, on the other hand, is dependent on the soil resistance; therefore, solving for the response of a pile under lateral loading is one of a class of soil-structure-interaction problems. The conditions of compatibility and equilibrium must be satisfied between the pile and soil and between the pile and the superstructure. Thus, the deformation and movement of the superstructure, ranging from a concrete mat to an offshore platform, and the manner in which the pile is attached to the superstructure, must be known or computed in order to obtain a correct solution to most problems. 2-1-1 Influence of Pile Installation and Loading on Soil Characteristics 2-1-1-1 General Review The most critical factor in solving for the response of a pile under lateral loading is the prediction of the soil resistance at any point along a pile as a function of the pile deflection. Any serious attempt to develop predictions of soil resistance must address the stress-deformation characteristics of the soil. The properties to be considered, however, are those that exist after the pile has been installed. Furthermore, the influence of lateral loading on soil behavior must be taken into account. The deformations of the soil from the driving of a pile into clay cause important and significant changes in soil characteristics. Different but important effects are caused by driving of piles into granular soils. Changes in soil properties are also associated with the installation of bored piles. While definitive research is yet to be done, evidence clearly shows that the soil immediately adjacent to a pile wall is most affected. Investigators (Malek, et al., 1989) have suggested that the direct-simple-shear test can be used to predict the behavior of an axially loaded pile, which suggests that the soil just next to the pile wall will control axial behavior. However, the lateral deflection of a pile will cause strains and stresses to develop from the pile 11 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading wall to several diameters away. Therefore, the changes in soil characteristics due to pile installation are less important for laterally loaded piles than for axially loaded piles. The influence of the loading of the pile on soil response is another matter. Four classes of lateral loading can be identified: short-term, repeated, sustained, and dynamic. The first three classes are discussed herein, but the response of piles to dynamic loading is beyond the scope of this document. The use of a pseudo-horizontal load as an approximation in making earthquakeresistant designs should be noted, however. The influence of sustained or cyclic loading on the response of the soil will be discussed in some detail in Chapter 3; however, some discussion is appropriate here to provide a basis for evaluating the models that are presented in this chapter. If a pile is in granular soil or overconsolidated clay, sustained loading, as from earth pressure, will likely cause only a negligible amount of long-term lateral deflection. A pile in normally consolidated clay, on the other hand, will experience long-term deflection, but, at present, the magnitude of such deflection can only be approximated. A rigorous solution requires solution of the threedimensional consolidation equation stepwise with time. At some time, the pile-head will experience an additional deflection that will cause a change in the horizontal stresses in the continuum. Methods have been developed, as reviewed later, for getting answers to the problem of short-term loading by use of correlations between soil response and the in situ undrained strength of clay and the in-situ angle of internal friction for granular soil. Such “backbone” solutions are important because they can be used for sustained loading in some cases and because an initial condition is provided for taking the influence of repeated loading into account. Experience has shown that the loss of lateral resistance due to repeated loading is significant, especially if the piles are installed in clay below free water. The clay can be pushed away from the pile wall and the soil response can be significantly decreased. Predictions for the effect of cyclic loading are given in Chapter 3. Four general types of loading are recognized above and each of these types is further discussed in the following sections. The importance of consideration and evaluation of loading when analyzing a pile subjected to lateral loading cannot be overemphasized. Many of the load tests described later in this chapter were performed by applying a lateral load in increments, holding that load for a few minutes, and reading all the instruments that gave the response of the pile. The data that were taken allowed p-y curves to be computed; analytical expressions are developed from the experimental results and these expressions yield p-y curves that are termed “static” curves. Repeated loadings were applied as well, as will be discussed in a following section. 2-1-1-2 Static Loading The static p-y curves can be thought of as backbone curves that can be correlated to some extent with soil properties. Thus, the curves are useful for providing some theoretical basis to the p-y method. From the standpoint of design, the static p-y curves have application in the following cases: where loadings are short-term and not repeated (probably not encountered); and for sustained loadings, as in earth-pressure loadings, where the soil around the pile is not susceptible to consolidation and creep (overconsolidated clays, clean sands, and rock). 12 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading As will be noted later in this chapter, the use of the p-y curves for repeated loading, a type of loading that is frequently encountered in practice, will often yield significant increases in pile deflection and bending moment. The engineer may wish to make computations with both the static curves and with the repeated (cyclic) curves so that the influence of the loading on pile response can be seen clearly. 2-1-1-3 Repeated Cyclic Loading The full-scale field tests that were performed included repeated or cyclic loading as well as the static loading described above. An increment of load was applied, the instruments were read, and the load was repeated a number of times. In some instances, the load was forward and backward, and in other cases only forward. The instruments were read after a given number of cycles and the cycling was continued until there was no obvious increase in ground line deflection or in bending moments. Another increment was applied and the procedure was repeated. The final load that was applied brought the maximum bending moment close to the moment that would cause the steel to yield plastically. Four specific sets of recommendations for p-y curves for cyclic loading are described in Chapter 3. For three of the sets, the recommendations that are given are for the “lower-bound” case. That is, the data that were used to develop the p-y curves were from cases where the ground-line deflection had substantially ceased with repetitions in loading. In the other case, for stiff clay where there was no free water at the ground surface, the recommendations for p-y curves are based on the number of cycles of load application, as well as other factors. The presence of free water at or near the ground surface for clay soils can be significant in regard to the loss of soil resistance due to cyclic loading (Long, 1984). After a deflection is exceeded that is based on the “elastic” response of the soil, a space opens between the pile and the soil when the load is released. Free water moves into this space and on the next load application, the water is ejected and soil may be eroded. This erosion causes a loss of soil resistance in addition to the losses due to remolding of the soil resulting from the cyclic strains. At this point, the use of judgment in the design of the piles under lateral load should be emphasized. If, for example, the clay is below a layer of sand, or if a provision could be made to supply sand around the pile, the sand will settle into the opening around the pile and partially restore the soil resistance that was lost due to the cyclic loading. Pile-supported structures are subjected to cyclic loading in many cases. Some common cases are wind loading on overhead signs and high-rise buildings, traffic loads on bridges, wave loadings on offshore structures, impact loads against docks and dolphin structures, and ice loads against locks and dams. The nature of the loading must be considered carefully. Factors to be considered are frequency, magnitude, duration, and direction. The engineer will be required to use a considerable amount of judgment in the selection of the soil parameters and response curves. 2-1-1-4 Sustained Loading If the soil resisting the lateral deflection of a pile is overconsolidated clay, the influence of sustained loading would probably be small. The maximum lateral stress from the pile against the clay would probably be less than the previous lateral stress; thus, the additional deflection due to consolidation and creep in the clay should be small or negligible. 13 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading If the soil that is effective in resisting lateral deflection of a pile is a granular material that is freely-draining, the creep would be expected to be small in most cases. However, if the pile is subjected to vibrations, there could be densification of the sand and a considerable amount of additional deflection. Thus, the judgment of the engineer in making the design should be brought into play. If the soil resisting lateral deflection of a pile is soft, saturated clay, the stress applied by the pile to the soil could cause a considerable amount of additional deflection due to consolidation (if positive pore water pressures were generated) and creep. An initial solution could be made, the properties of the clay could be employed, and an estimate could be made of the additional deflection. The p-y curves could be modified to reflect the additional deflection and a second solution obtained with the computer. In this manner, convergence could be achieved. The writers know of no rational way to solve the three-dimensional, time-dependent problem of the additional deflection that would occur so, again, the judgment and integrity of the engineer will play an important role in obtaining an acceptable solution. 2-1-1-5 Dynamic Loading Two types of problems involving dynamic loading are frequently encountered in design: machine foundations and earthquakes. The deflection from the vibratory loading from machine foundations is usually quite small and the problem would be solved using the dynamic properties of the soil. Equations yielding the response of the structure under dynamic loading would be employed and the p-y method described herein would not be employed. With regard to earthquakes, a rational solution should proceed from the definition of the free-field motion of the near-surface soil due to the earthquake. Thus, the p-y method described herein could not be used directly. In some cases, an approximate solution to the earthquake problem has been made by applying a horizontal load to the superstructure that is assumed to reflect the effect of the earthquake. In such a case, the p-y method can be used but such solutions would plainly be approximate. 2-1-2 Models Used in Analyses of Laterally Loaded Single Piles A number of models have been developed for the pile and soil system. The following are brief descriptions for a few of them. 2-1-2-1 Elastic Pile and Soil The model shown in Figure 2-1(a) depicts a pile in an elastic soil. A model of this sort has been widely used in analysis. Terzaghi (1955) gave values of subgrade modulus that can be used to solve for deflection and bending moment, but he went on to qualify his recommendations. The standard equation for a beam-column was employed in a manner that had been suggested by earlier writers such as Hetenyi (1946). Terzaghi stated that the tabulated values of subgrade modulus should not be used for cases where the computed soil resistance was more than one-half of the bearing capacity of the soil. However, he provided no recommendations for the computation of bearing capacity under lateral load, nor did he provide any comparisons between the results of computations and experiments. The values of subgrade moduli published by Terzaghi proved to be useful and provide evidence that Terzaghi had excellent insight into the problem. However, in a private conversation with Professor Lymon Reese, Terzaghi said that he had not been enthusiastic about 14 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading writing the paper and only did so in response to numerous requests. The method illustrated by Figure 2-1(a) serves well in obtaining the response of a pile under small loads, in illustrating the various interrelationships in the response, and in giving an overall insight into the nature of the problem. The method cannot be employed without modification in solving for the loading at which a plastic hinge will develop in the pile. P M V (a) (b) P M M V V kh Lateral Translational Spring k Vertical Side Shear Moment Spring Center of Rotation kb Base Moment Spring kb Base Shear Translational Spring (c) (d) Figure 2-1 Models of Piles Under Lateral Loading, (a) 3-Dimensional Finite Element Mesh, and (b) Cross-section of 3-D Finite Element Mesh, (c) Brom’s Model, (d) MFAD Model 15 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading 2-1-2-2 Analysis Using the Finite Element Method The case shown in Figure 2-1(b) is the same as the previous case except that the soil has been modeled by finite elements. No attempt is made in the sketch to indicate an appropriate size of the element mesh, boundary constraints, special interface elements, most favorable shape of elements, or other details. The finite elements may be axially symmetric with non-symmetric loading or full three-dimensional models. The elements of various types may be used. In view of the computational power that is now available, the model shown in Figure 21(b) appears to be practical to solve the pile problem. The elements can be three-dimensional and material models may be nonlinear. However, the selection of an appropriate material model for the soil involves not only the parameters that define the model, but methods for dealing with other factors such as volume change and unloading. These factors also include development of tensile stresses in the soil, modeling of layered soils, development of separation and closure of gapping between pile and soil during repeated loading, and the changes in soil characteristics that are associated with the various types of loading and construction. Yegian and Wright (1973) and Thompson (1977) used a plane-stress finite element model and obtained soil-response curves that agree well with results at or near the ground surface from full-scale experiments. The writers are aware of research that is underway with threedimensional, nonlinear, finite and boundary elements, and are of the opinion that in time such a model will lead to results that can be used in practice. 2-1-2-3 Rigid Pile and Plastic Soil Broms (1964a, 1964b, 1965) employed the model shown in Figure 2-1(c) to derive equations for the loading that causes a failure, either because of excessive stresses in the soil or because of a plastic hinge, or hinges, in the pile. The rigid pile is assumed and a solution is found using the equations of statics for the distribution of ultimate resistance of the soil that puts the pile in equilibrium. The soil resistance shown hatched in the Figure 2-1(c) is for cohesive soil, and a solution was developed for cohesionless soil as well. After the ultimate loading is computed for a pile of particular dimensions, Broms suggests that the deflection at the working load may be computed by the use of the model shown in Figure 2-1(c). Broms’ method makes use of several simplifying assumptions but is useful for the initial selection of a pile for a given soil and for a given set of loads. 2-1-2-4 Rigid Pile and Four-Spring Model for Soil The model shown in Figure 2-1 (d) was developed for the design of short, stiff piles that support transmission towers (DiGioia, et al., 1989). The loading applied to the pile head includes shear force, overturning moment and axial load. The four reaction spring types are: a rotational spring at the pile tip that responds to the rotation of the tip, a linear spring at the pile tip that responds to the axial movement of the tip, a set of linear springs parallel to the pile wall that respond to vertical movement of the pile, and a set of linear springs normal to the sides of the pile that respond to lateral deflection. The model was developed using analytical techniques and tested against a series of experiments performed on short piles. However, the experimental procedures did not allow the independent determination of the curves that give the forces as a function of the four different 16 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading types of movement. Therefore, the relative importance of the four types of soil resistance has not been found by experiment, and the use of the model in practice has been limited to the design of short, stiff foundations with length to diameter ratios typically less than five. 2-1-2-5 Nonlinear Pile and p-y Model for Soil The model shown in Figure 2-2 represents the one utilized by LPile. The loading on the pile is two-dimensional consisting of shear, overturning moment, and axial thrust. No torsion or out-of-plane bending is included in the model. The horizontal lines across the pile are meant to show that it is made up of different sections; for example, a steel pipe could be used with changes in wall thickness or step-tapered as shown here. The difference-equation method is employed for the solution of the beam-column equation to allow the different values of bending stiffness to be addressed. In addition, it is possible to vary the bending stiffness with respect to the bending curvature that is computed during the iterative solution. P M y V p y p y p y p y p y x Figure 2-2 Model of a Pile Under Lateral Loading and p-y Curves An axial thrust load is included and is considered in the solution with respect to its effect on bending, but not in respect to the development of axial settlement. However, as shown later in this manual, the computational procedure allows for the determination of the magnitude of the axial thrust load at which a pile will buckle. The soil around the pile is replaced by a set of nonlinear springs that indicate that the soil resistance p is a nonlinear function of pile deflection y. The nonlinear springs and the corresponding curves that model their behavior are widely spaced in the figure, but are actually spaced at every nodal point on the pile. As may be seen, the p-y curves are nonlinear with respect to depth x along the pile and lateral deflection y. The top p-y curve is drawn to indicate that the pile may deflect a finite distance with no soil resistance. The second curve from the top is drawn to show that the soil resistance is deflection softening. There is no reasonable limit to the variations in the resistance of the soil to the lateral deflection of a pile. 17 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading As will be shown later, the p-y method is versatile and provides a practical means for design. The method was first suggested by McClelland and Focht (1956). Two technological developments during the 1950’s made implementation of the method possible: the development of digital computer programs for solving a nonlinear, fourth-order differential equation; and the development of electrical resistance strain gauges for use in obtaining soil-response (p-y) curves from full-scale lateral load tests of piles. The p-y method was developed originally from proprietary research sponsored by the petroleum industry in the 1950’s and 1960’s. At the time, large piles were being designed for to support offshore oil production platforms that were to be subjected to exceptionally large horizontal forces from storm waves and wind. Rules and recommendations for the use of the p-y method for design of such piles are presented by the American Petroleum Institute (2010) and Det Norske Veritas (1977). The use of the method has been extended to the design of onshore foundations. For example, the Federal Highway Administration (USA) has sponsored a reference publication dealing with the design of piles for transportation facilities (Reese, 1984). The method is being cited broadly by Jamiolkowski (1977), Baguelin, et al. (1978), George and Wood (1976), and Poulos and Davis (1980). The method has been used with apparent success for the design of piles; however, research is continuing up to the present. 2-1-2-6 Definition of p and y The definitions of the quantities p and y as used in this document are necessary because other definitions have been used. The sketch in Figure 2-3(a) shows a uniform distribution of radial stresses, normal to the wall of a non-displaced cylindrical pile. This distribution of stresses is correct for a pile that has been installed without bending. If the pile is displaced a distance y (the amount of the displacement is exaggerated in the sketch for clarity), the distribution of stresses becomes non-uniform and will be similar to that shown in Figure 2-3 (b). The stresses will have decreased on the backside of the pile and increased on the front side. Some of the unit stresses have both normal and shearing components. p y (a) (b) Figure 2-3 Distribution of Stresses Acting on a Pile, (a) Before Lateral Deflection and (b) After Lateral Deflection y 18 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Integration of the unit stresses around the perimeter of the pile results in the lateral load intensity p, which acts opposite to the direction of pile displacement y. The dimensions of p are force per unit length of the pile. These definitions of p and y are convenient in the solution of the differential equation and are consistent with those used in the solution of the elastic beam equation. Direction of Pile Displacement The distribution of shear stresses in the soil around the pile is known to be more complex than the simplified version shown in Figure 2-3. The results of a nonlinear finite element stress analysis to determine the distribution of shear stresses around a laterally load pile is shown in Figure 2-4. Figure 2-4 Variation of Shear Stresses in Pile and Soil for Displaced Pile The reader should note the fineness of the finite element mesh utilized in the analysis presented in Figure 2-4. Experience has found that use of fine meshes is necessary to obtain stress distributions in the pile that are accurate enough to permit evaluation of the bending moment developed in the pile. 2-1-2-7 Procedure for Developing Experimental p-y Curves Most models for p-y curves have been derived from analyses of full-size load tests. When performing a load test on a pile subjected to lateral loading, strain gages may be installed along the length of the pile. This permits direct measurement of strain and evaluation of the curvature developed at the locations of the strain gages. Values of bending moment at the locations of the strain gages can be computed from the values of curvature. Other direct measurements are the applied lateral load and displacement of the pile head in terms of lateral displacement and pilehead rotation. All other structural responses in the pile and the inferred lateral load transfer from the pile to the soil must be inferred from the available measurement of pile response under load. 19 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading The quality of the interpreted results from the load test depends on the quantity, accuracy, and consistency of the direct measurements on pile response. In contrast to the direct measurements on the pile behavior, it is neither simple nor practical to make direct measurements in the soil and rock surrounding the pile. Usually, the soil properties at the site are measured prior to the construction of the test pile, but no measurements of soil behavior are measured during the performance of the load test. The method used to develop the experimentally measured p-y curve is the following. At each level of pile-head loading, first fit analytical curves to the measured values of pile curvature and bending moment developed along the length of the pile. Compute values of lateral load intensity, p, along the length of the pile by computing second derivative of bending moment versus depth. Next, compute the lateral displacement profile along the length of the pile by double integrating the curve of curvature along the length of the pile. Lastly, tabulate the corresponding values of p and y at the depths of the measurements. After this has been done for all levels of loading, it is possible to plot the p-y curves at each depth of measurement. 2-1-2-8 Comments on the p-y method The most common criticism of the p-y method is that the soil is not treated as a continuum, but instead as a series of discrete springs (i.e. the Winkler model). Several comments can be given in response to this valid criticism. The recommendations for the computation of p-y curves for use in the analysis of piles, given in Chapter 3, are based for the most part on the results of full-scale experiments, where the “continuum effect” was explicitly satisfied. Further, Matlock (1970) performed some tests of a pile in soft clay where the pattern of pile deflection was varied along its length. The p-y curves that were derived from each of the loading conditions were essentially the same. Thus, Matlock found that experimental p-y curves from fully instrumented piles could predict, within reasonable limits, the response of a pile whose head is free to rotate or is fixed against rotation. The methods for computing p-y curves derived from correlations to the results of fullscale experiments have been used to make computations for the response of piles where only the pile-head movements were recorded. These computations, some of which are shown in Chapter 6 of the User’s Manual for LPile, show reasonable to excellent agreement between computed predictions and experimental measurements. Finally, technology may advance so that the soil resistance for a given deflection at a particular point along a pile can be modified quantitatively to reflect the influence of the deflection of the pile above and below the point in question. In such a case, multi-valued p-y curves can be developed at every point along the pile. The analytical solution that is presented herein could be readily modified to deal with the multi-valued p-y curves. In short, the p-y method has some limitations; however, there is much evidence to show that the method yields information of considerable value to an analyst and designer. 2-1-3 Computational Approach for Single Piles The general procedure to be used in computing the behavior of many piles under lateral loading is illustrated in Figure 2-5. Figure 2-5 (a) shows a pile with a given size embedded in a soil with known properties. A lateral load V, axial load P, and moment M are acting at the pile head. The design loading presumably would have been found by considering the unfactored 20 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading loads acting on the superstructure. Each of the loads is decreased or increased by an appropriate load factor and, for each combination of loads, a solution of the problem is found. A curve can be plotted, such as shown by the solid line in Figure 2-5 (b), which will show the maximum bending moment developed in the pile as a function of the level of loading. With the value of the nominal bending moment capacity Mnom for the section that takes into account the axial loading, the “failure loading” can be found. An assumption is made that development of a plastic hinge at any point in the pile would not be acceptable. The failure loading is then divided by a global factor of safety to find the allowable loading. The allowable loading is then compared to the loading from the superstructure to determine if the pile that was selected was satisfactory. An alternate approach makes use of the concept of partial safety factors. The parameters that influence the resistance of the pile to lateral loading are factored and the curve shown by the dashed line is computed. As shown in Figure 2-5, smaller values of the failure loading would be found. The values of allowable loading would probably be about the same as before with the loading being reduced by a smaller value of partial safety factor. In the case of a very short pile, the performance failure might be due to excessive deflection as the pile “plows” through the soil. The design engineer can then employ a global factor of safety or partial factors of safety to set the allowable load capacity. As shown in Figure 2-5(b), the bending moment is a nonlinear function of load; therefore, the use of allowable bending stresses, for example, is inappropriate and perhaps unsafe. A series of solutions is necessary in order to obtain the allowable loading on a pile; therefore, the use of a computer is required. P M Loading V Loading at Failure Mult Allowable Loading Maximum Bending Moment (a) (b) Figure 2-5 Illustration of General Procedure for Selecting a Pile to Sustain a Given Set of Loads The next step in the computational process is to solve for the deflection of the pile under the allowable loading. The tolerable deflection is frequently limited by special project requirements and probably should not be dictated by building codes or standards. Among factors 21 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading to be considered are machinery that is sensitive to differential deflection and the comfort of humans on structures that move a sensible amount under loading. The computation of the load at failure requires values of the nominal bending moment capacity and flexural rigidity of the section. Because the analyses require the structural section to be stressed beyond the linear-elastic range, a computer program is required to compute the nonlinear properties of the section. These capabilities are included in the LPile program. General guidelines about making computations for the behavior of a pile under lateral loading are presented in this manual. In addition, several examples are presented in detail in the User’s Manual for LPile. However, it should be emphasized that a full design involves consideration of many other factors that are not addressed here. 2-1-4 Pile Buckling Analysis A common design problem is the analysis of the pile buckling capacity. In this problem, shown in Figure 2-6(a), a pile that extends above the ground line is subjected to a lateral load V and an axial load P. As part of the design process, the engineer desires to evaluate the axial load that will cause the pile to buckle. The lateral load is held constant at the maximum value and the axial load is increased in increments. The deflection yt at the top of the pile is plotted as a function of axial load, as shown in Figure 2-6(b). A value of axial load will be approached at which the pile-head deflection will increase without limit. This load is selected for the buckling load. It is important that the buckling load be found by starting the computer runs with smaller values of axial load because the computer program fails to obtain a solution at axial loads above the buckling load. An example analysis of pile buckling is presented in Section 4-4 of this manual and an example problem is presented in the User’s Manual for LPile. P yt P V Buckling Load yt (b) (a) Figure 2-6 Analysis of Pile Buckling 22 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading 2-1-5 Analysis of Critical Pile Length Another common design problem is illustrated in Figure 2-7. A pile is subjected to a combination of loads, as shown in Figure 2-7(a), but the axial load is relatively small so that the length of the pile is controlled by the magnitude of the lateral load. Factored values of the loads are applied to the top of a pile that is relatively long and a computer run is made to solve for the lateral deflection yt and a point may be plotted in Figure 2-7(b). A series of runs are made with the length of the pile reduced in increments. Connecting the points for the deflection at the top of the pile yields the curve in Figure 2-7 (b). These computations and generation of the critical length curve can be automatically performed by LPile for individual load cases that include pilehead shear force(either shear and moment, shear and fixed rotation, or shear and rotational stiffness pile-head loading conditions). The curve in Figure 2-7 (b) shows that the value of yt is unchanged for pile lengths longer than a length that is termed Lcrit and that values of lateral deflection are larger for smaller values of pile length. The designer will normally select a pile for a particular application whose length is somewhat greater than Lcrit. Another use of the critical length is to determine the length of pile required not to accumulate a permanent inclination of the pile after lateral loading. The shorter a pile is relative to the critical length, the more likely it is to develop a permanent inclination after loading. Thus, if it is required that a structure remain upright within a specified tolerance, the foundation piles should be longer than the critical length. P M yt V Lcrit L Lcrit Pile Length Figure 2-7 Solving for Critical Pile Length 2-1-6 Occurrences of Lateral Loads on Piles Piles that sustain lateral loads of significant magnitude occur in offshore structures, waterfront structures, bridges, buildings, industrial plants, navigation locks, dams, and retaining walls. Piles can also be used to stabilize slopes against sliding that either have failed or have a low factor of safety. The lateral loads may be derived from earth pressures, wind, waves and 23 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading currents, earthquakes, impact, moving vehicles, and the eccentric application of axial loads. In numerous cases, the loading of the piles cannot be obtained without consideration of the stresses and deformation in the particular superstructure. Structures where piles are subjected to lateral loading are discussed briefly in the following paragraphs. Some general comments are presented about analytical techniques. The cases that are selected are not comprehensive but are meant to provide examples of the kinds of problems that can be attacked with the methods presented herein. In each of the cases, the assumption is made that the piles are widely spaced and the distribution of loading to each of the piles in a group is neglected. 2-1-6-1 Offshore Platform An offshore platform is illustrated in Figure 2-8(a). A three-dimensional analysis of such a structure is sometimes necessary, but often a two-dimensional analysis is adequate. The preferred method of analysis of the piles is to consider the full interaction between the superstructure and the supporting piles. However, in many analyses, the piles are replaced by nonlinear load-transfer reactions: axial load versus axial movement, lateral load versus lateral deflection, and moment versus lateral deflection. A simplified method of analyzing a single pile is illustrated in the figure. h = 6.1 m St h Mt 3.5EI c M d = 838 mm Ic = 5.876 x 10-3 m4 4m V V M d = 762 mm Ip = 3.07 x 10-3 m4 E = 2 x 108 kPa (a) (b) (c) Figure 2-8 Simplified Method of Analyzing a Pile for an Offshore Platform The second pile is shown in Figure 2-8(b). In typical conditions, the annular void between the jacket leg and the head of the pile was sealed with a flexible gasket and the annular space is filled with grout. Consequently, it is usually assumed that the bending and lateral deflection in the pile and jacket leg will be continuous and have the same curvature. The sketch in Figure 2-8(c) shows that the stiffness of the braces was neglected and that the rotational restraint at the upper panel point was intermediate between being fully fixed and 24 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading fully free. The assumption is then made that the resultant force on the bent can be equally divided among the four piles, giving a known value of Pt. The second boundary condition at the top of the pile is the value of the rotational restraint, Mt/St, which is taken as 3.5EIc/h, where EIc is the combined bending stiffness of the pile and the jacket leg. The p-y curves for the supporting soil can be generated, and the deflection and bending moment along the length of the pile can be computed. The above method is approximate. However, a pile with the approximate geometry can be rapidly modeled by the p-y method. In addition, there may be structures for which the pile head is neither completely fixed nor free and the use of rotational restraint for the pile-head fixity condition is required. The implementation of the method outlined above is shown by Example 3 in the User’s Manual for LPile provided with LPile. In addition to investigating the exact value of pile-head rotational stiffness, the designer should consider the rotation of the superstructure due principally to the movement of the piles in the axial direction. This rotation will affect the boundary conditions at the top of the piles. 2-1-6-2 Breasting Dolphin One application of a pile under lateral load is a large pile used as a foundation for a breasting dolphin. Figure 2-9(a) depicts a vessel with mass m approaching a freestanding pile. The velocity of the vessel is v and its kinetic energy on impact with the dolphin would be ½mv2. The deflection of the dolphin could be computed by finding the area under the load-deflection curve that would equate to the energy of the vessel. The design engineer should be concerned with a number of parameters in the problem. The level of water could vary due to tide levels, requiring a number of solutions. The pile could be tapered to give it the proper strength to sustain the computed bending moment while at the same time making it as flexible as possible. With the first impact of a vessel, the soil will behave as if it were under static loading (assuming no inertia effects in the soil) and would be relatively stiff. With repeated loading on the pile from berthing, the soil will behave as if under cyclic loading. The appropriate p-y curves would need to be used, depending on the number of applications of load. A single pile, or a group of piles, could support a primary fender, but the exact types and sizes of cushions or fenders to be used between the vessel and the pile need to be selected on the basis of the vessel size and berthing velocity. It should be noted that fenders must be mounted properly above the waterline to prevent damage to the berthing vessels and that the lateral spacing of breasting dolphins will depend on the overall length of the vessel and the vessel’s curvature near the bow and stern. 25 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Load m, v Breasting Dolphin Deflection Figure 2-9 Analysis of a Breasting Dolphin 2-1-6-3 Single-Pile Support for a Bridge A common design used for the support of a bridge is shown in Figure 2-10. The design provides more space under the bridge in an urban area and may be aesthetically more pleasing than multiple columns. As may be seen in the sketch, the primary loads that must be sustained by the pile lie in a plane perpendicular to the axis of the bridge. The loads may be resolved into an axial load, a lateral load, and a moment at the ground surface or, alternately, at the top of the column. The braking forces are shown properly in a plane parallel to the axis of the bridge and can be large, if heavily loaded trucks are suddenly brought to a stop on a downward-sloping span. The deflection that may be possible in the direction of the axis of the bridge is probably limited to that allowed by the joints in the bridge deck. Thus, one of the boundary conditions for the piles for such loading could be a limiting deflection. If it is decided that significant loads can be acting simultaneously in perpendicular planes, two independent solutions can be made, and the resulting bending moments can be added algebraically. Such a procedure would not be perfectly rigorous but should yield results that will be instructive to the designer. 26 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Loads From Traffic Loads From Braking and Wind Forces From Dead Loads From Wind and Other Forces Figure 2-10 Loading On a Single Shaft Supporting a Bridge Deck 2-1-6-4 Pile-Supported Overhead Sign The sketches in Figure 2-11 show two schemes for piles to support an overhead sign. Many such structures are used in highways and in other transportation facilities. Similar schemes could be used for the foundation of a tower that supports power lines. The loadings on the foundation from the wind will be a lateral load and a relatively large moment; a small axial load will result from the dead weight of the superstructure. The lateral load and moment will be variable because the wind will blow intermittently and will gust during a storm. The predominant direction of the wind will vary; these factors should be taken into account in the analysis. The sketch in Figure 2-11(a) shows a two-pile foundation. The lateral load and axial load will be divided between the two piles, and the moment will be carried principally by tension in one pile and compression in the other. The lateral load will cause each of the piles to deflect, and there will be a bending moment along each pile. In performing the analysis for lateral loading, py curves must be derived for the supporting soil with repeated loading being assumed. A factored load must be used, and the degree of fixity of the pile heads must be assessed. The connection between the piles and the cap may be such that the pile heads are essentially free to rotate. Alternatively, the design analysis may be made assuming that the pile heads are fixed against rotation. 27 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Wind Load Wind Load Column Dead Load Pile Cap Column Dead Load Two-Shaft Foundation (a) Single-Shaft Foundation (b) Figure 2-11 Foundation Options for an Overhead Sign Structure The pile heads, under almost any designs, will likely be partially restrained, or at some point between fixed and free. An interesting exercise is to take a free body of the pile from the bottom of the cap and to analyze its behavior when a shear and a moment are applied at the end of this “stub pile. “ The concrete in this instance will serve a similar function as the soil along the lower portion of the pile. The rotational restraint provided by the concrete can be computed by use of an appropriate model, perhaps by using finite elements. At present, an appropriate analytical technique, when a pile head extends into a concrete cap or mat, is to assume various degrees of pile-head fixity, ranging from completely fixed to completely free, and to design for the worst conditions that results from the computer runs. The sketch in Figure 2-11(b) shows a structure supported by a single pile. Shown in the figure is a pattern of soil resistance that must result to put the pile into equilibrium. In performing the analyses, the p-y curves must be derived as before, but, in this instance, the conditions at the pile head are fully known. The loading will consist of a shear and a relatively large moment, and the pile head will be free to rotate. Because the axial load will be relatively small, studies will probably be necessary to determine the required penetration of the pile so that the tip deflection will be small and the pile will not behave as a “fence post. “ Of the two schemes, selection of the most efficient scheme will depend on a number of conditions. Two considerations are the deflection under the maximum load at the top of the structure and the availability of equipment that can construct the large pile. 2-1-6-5 Use of Piles to Stabilize Slopes An application for piles that is continuing interest is the stabilizing of slopes that have failed or are judged to be near failure. The sketch in Figure 2-12 illustrates the application. A bored pile is often employed because it can be installed with a minimum of disturbance of the soil near the actual or potential sliding surface. 28 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Figure 2-12 Use of Piles to Stabilize a Slope Failure The procedures for the design of such a pile are described in some more detail later in this manual. The special treatment accorded to this particular problem is due to its importance and because the technical literature fails to provide much guidance to the designer. 2-1-6-6 Anchor Pile for a Tieback The use of a pile as the anchor for a tieback anchor is illustrated in Figure 2-13. A vertical pile is shown in the sketch with the tie rod attached below the top of the pile. The force in the rod can be separated into components; one component indicates the lateral load on the pile and the other the axial load. The p-y curves are derived with proper attention to soil characteristics with respect to depth below the ground surface. The loading will be sustained and a proper adjustment must be made, if time-related deflection is expected. The analysis will proceed by considering the loading to be applied at the top of the pile or, preferably, as a distributed load along the upper portion of the pile. In the case of the anchor that is shown in Figure 2-13, the load is applied at some distance below the pile head. The anchor pile can be modelled using the methods presented in Section 3-8-1-6 in the User’s Manual for LPile. 2-1-6-7 Other Uses of Laterally Loaded Piles Piles under lateral loading occur in many structures or applications other than the ones that were mentioned earlier. Some of these are high-rise buildings that are subjected to forces from wind; structures subject to unbalanced earth pressures; pile-supported retaining walls; locks and dams; waterfront structures such as piers and quay walls; supports for overhead pipes and for other facilities found in industrial plants; and bridge abutments. The method has the potential of analyzing the flexible bulkhead that is shown in Figure 2-13. The sheet piles (or tangent piles if drilled shafts or bored piles are used) can be analyzed as a pile, if the p-y curves are modified to reflect the soil resistance versus deflection for a wall, rather than of an individual pile. Research on the topic has been performed (Wang, 1986) and has been implemented in the computer program PYWall from Ensoft, Inc. 29 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Tie-back Anchor Pile (Dead Man) Sheet Pile Wall Figure 2-13 Anchor Pile for a Flexible Bulkhead 2-2 Derivation of Differential Equation for the Beam-Column and Methods of Solution The equation for the beam-column must be solved for implementation of the p-y method, and a brief derivation is shown in the following section. An abbreviated version of the equation can be solved by a closed-form method for some purposes, but a general solution can be made only by a numerical procedure. Both of these kinds of solution are presented in this chapter. 2-2-1 Derivation of the Differential Equation In most instances, the axial load on a laterally loaded pile is of such magnitude that it has a small influence on bending moment. However, there are occasions when it is desirable to include the axial loading in the analytical process. The derivation of the differential equation for a beam-column foundation was presented by Hetenyi (1946). The derivation is shown in the following paragraphs, though the notation differs from that used by Hetenyi. The assumption is made that a bar on an elastic foundation is subjected not only to the vertical loading, but also to the pair of compressive forces Px acting at the centroid of the end cross-sections of the bar. If an infinitely small unloaded element, bounded by two verticals a distance dx apart, is cut out of this bar (see Figure 2-14), the equilibrium of moments (ignoring second-order terms) leads to the equation M dM M Px dy Vv dx 0 ..........................................(2-1) or 30 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading y x y Px S M Vv Vn Vv dx Vv+dVv y+dy M+dM Px x Figure 2-14 Element of Beam-Column (after Hetenyi, 1946) dM dy Px Vv 0 . ....................................................(2-2) dx dx Differentiating Equation 2-2 with respect to x, the following equation is obtained d 2M d 2 y dVv Px 2 0 ................................................(2-3) dx dx 2 dx The following definitions are noted: d 2M d4y EI 4 dx 2 dx dVv p dx p Es y where Es is equal to the secant modulus of the soil-response curve. And making the indicated substitutions, Equation 2-3 becomes EI d4y d2y P E s y 0 ...............................................(2-4) x dx 4 dx 2 The direction of the shearing force Vv is shown in Figure 2-14. The shearing force in the plane normal to the deflection line can be obtained as 31 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Vn = Vv cos S – Px sin S ..................................................(2-5) Because S is usually small, we may assume the small angle relationships cos S = 1 and sin S = tan S = dy/dx. Thus, Equation 2-6 is obtained. Vn Vv Px dy .........................................................(2-6) dx Vn will mostly be used in computations, but Vv can be computed from Equation 2-6 where dy/dx is equal to the rotation S. The ability to allow a distributed force W per unit of length along the upper portion of a pile is convenient in the solution of a number of practical problems. The differential equation then becomes as shown below. d4y d2y EI 4 Px 2 p W 0 .............................................(2-7) dx dx where: Px = axial thrust load in the pile, y = lateral deflection of the pile at a point x along the length of the pile, p = soil reaction per unit length, EI = flexural rigidity, and W = distributed load along the length of the pile. Other beam formulas that are needed in analyzing piles under lateral loads are: Vv EI d3y dy Px .....................................................(2-8) 3 dx dx d2y M EI 2 ...........................................................(2-9) dx and, S dy .............................................................(2-10) dx where Vv = horizontal shear in the pile, M = bending moment in the pile, and S = slope of the elastic curve relative to the x-axis of the pile. 32 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Except for the axial load Px, the sign conventions that are used in the differential equation and in subsequent development are the same as those commonly employed in the mechanics for beams, with the axes for the pile rotated 90 degrees clockwise from the axes for the beam. The axial load Px does not normally appear in the equations for beams. The sign conventions are presented graphically in Figure 2-15. A solution of the differential equation yields a set of curves such as shown in Figure 2-16, with a compressive axial load being defined as positive in sign. The mathematical relationships for the various curves that give the response of the pile are shown in the figure for the case where no axial load is applied. Slope (L/L) Deflection (L) y y(+) S (+) x Moment (F*L) y y M (+) x x P (+) Axial Force (F) Soil Resistance (F/L) Shear (F) y y y V (+) p (+) x x x Figure 2-15 Sign Conventions The assumptions that are made in deriving the differential equation are: 1. The pile is initially straight and has a uniform cross section, 2. The pile has a longitudinal plane of symmetry; loads and reactions lie in that plane, 3. The pile material is homogeneous, 4. The proportional limit of the pile material is not exceeded, 5. The modulus of elasticity of the pile material is the same in tension and compression, 6. Transverse deflections of the pile are small, 7. The pile is not subjected to dynamic loading, and 8. Deflections due to shearing stresses are small. 33 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Assumption 8 can be addressed by including more terms in the differential equation, but errors associated with omission of these terms are usually small. The numerical method presented later can deal with the behavior of a pile made of materials with nonlinear stress-strain properties. y S M V p Figure 2-16 Form of Results Obtained for a Complete Solution 2-2-2 Solution of Reduced Form of Differential Equation A simpler form of the differential equation results from Equation 2-4, if the assumptions are made that no axial load is applied, that the bending stiffness EI is constant with depth, and that the soil modulus Es is constant with depth and equal to . The first two assumptions can be satisfied in many practical cases; however, the last of the three assumptions seldom occurs or is ever satisfied in practice. The solution shown in this section is presented for two important reasons: (1) the resulting equations demonstrate several factors that are common to any solution; thus, the nature of the problem is revealed; and (2) the closed-form solution allows for a check of the accuracy of the numerical solutions that are given later in this chapter. If the assumptions shown above are employed and if the identity shown in Equation 2-11 is used, the reduced form of the differential equation is shown as Equation 2-12. 4 4 EI Es .....................................................(2-11) 4 EI d4y 4 4 y 0 ......................................................(2-12) 4 dx The solution to Equation 2-12 may be directly written as: 34 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading y e x (C1 cos x C 2 sin x) e x (C 3 cos x C 4 sin x) ..........................................(2-13) The coefficients C1, C2, C3, and C4 must be evaluated for the various boundary conditions that are desired. A pile of any length is considered later but, if one considers a long pile, a simple set of equations can be derived. An examination of Equation 2-13 shows that C1 and C2 must approach zero because the term ex will increase without limit. The boundary conditions for the top of the pile that are employed for the solution of the reduced form of the differential equation are shown by the simple sketches in Figure 2-17. A more complete discussion of boundary conditions for a pile is presented in the next section. Spring (takes no shear, but restrains pile head rotation) Mt y Vt Vt Free-head y Fixed-Head (a) Vt y Partially Restrained (b) (c) Figure 2-17 Boundary Conditions at Top of Pile 2-2-2-1 Solution for Free-head Pile The boundary conditions at the top of the pile selected for the first case are illustrated in Figure 2-17(a) and in equation form are: at x = 0, d 2 y Mt ..........................................................(2-14) dx 2 EI d 3 y Vt ...........................................................(2-15) dx 3 EI The differentiations of Equation 2-13 are made and the substitutions indicated by Equation 2-14 yield the following. 35 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading C4 Mt .........................................................(2-16) 2 EI 2 The substitutions indicated by Equation 2-15 yield the following. C3 C 4 Vt .....................................................(2-17) 2 EI 3 Equations 2-16 and 2-17 are used and expressions for deflection y, slope S, bending moment M, shear V, and soil resistance p can be written as shown in Equations 2-18 through 2-22. y 2b 2 e -bx Vt cos x M t (cos x sin x) ...............................(2-18) b 2V 2 M S e x t (sin x cos x) t cos x ............................(2-19) EI V M e x t sin x M t (sin x cos x) .................................(2-20) V e x Vt (cos x sin x) 2M t sin x ................................(2-21) V p 2 2 e x t cos x M t (cos x sin x) .............................(2-22) It is convenient to define some functions that make it easier to write the above equations. These are: A1 e x cos x sin x ..............................................(2-23) B1 e x cos x sin x ..............................................(2-24) C1 e x cos x ......................................................(2-25) D1 e x sin x ......................................................(2-26) Using these functions, Equations 2-18 through 2-22 become: y 2Vt C1 36 Mt B1 ...............................................(2-27) 2 EI 2 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading S 2Vt 2 M Vt A1 Mt C1 ...............................................(2-28) EI D1 M t A1 ....................................................(2-29) V Vt B1 2M t D1 ..................................................(2-30) p 2Vt C1 2M t 2 B1 .............................................(2-31) Values for A1, B1, C1, and D1, are shown in Figure 2-18 as a function of the nondimensional distance x along the pile. 2-2-2-2 Solution for Fixed-head Pile For a pile whose head is fixed against rotation, as shown in Figure 2-17(b), the solution may be obtained by employing the boundary conditions as given in Equations 2-32 and 2-33. dy 0 .............................................................(2-32) dx At x = 0, EI d3y Vt .........................................................(2-33) dx 3 Using the procedures as for the case where the boundary conditions were as shown in Figure 2-5(a), the results are as follows. C3 C 4 Vt ....................................................(2-34) 4 EI 3 The solution for long piles is given in Equations 2-35 through 2-39. y S Vt A1 ..........................................................(2-35) Vt D1 ......................................................(2-36) 2 EI 2 37 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading A1, B1, C1, D1 -0.25 0.0 0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 x A11 B11 C11 D1 1 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5 5.0 5.5 A1 e x cos x sin x B1 e x cos x sin x C1 e x cos x D1 e x sin x 6.0 Figure 2-18 Values of Coefficients A1, B1, C1, and D1 M Vt B1 .........................................................(2-37) 2 V Vt C1 ............................................................(2-38) p Vt A1 ........................................................(2-39) 2-2-2-3 Solution for Pile with Rotational Restraint It is sometimes convenient to have a solution for a third set of boundary conditions describing the rotational restraint of the pile head, as shown in Figure 2-17(c). For this boundary 38 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading condition, the rotational spring does not take any shear, but does restrain the rotation of the pile head. These boundary conditions are given in Equations 2-40 and 2-41. At the pile head, where x = 0, the rotational restrain is controlled by EI d2y dx 2 M t ........................................................(2-40) dy St dx and the pile-head shear force is controlled by d 3 y Vt ...........................................................(2-41) dx 3 EI Employing these boundary conditions, the coefficients C3 and C4 can be evaluated, and the results are shown in Equations 2-42 and 2-43. For convenience in writing, the rotational restraint Mt /St is given the symbol k. C3 Vt (2 EI k ) ..................................................(2-42) EI ( 4 3 k ) C4 k Vt ..................................................(2-43) EI ( 4 3 k ) These expressions can be substituted into Equation 2-13, differentiation performed as appropriate, and substitution of Equations 2-23 through 2-26 will yield a set of expressions for the long pile similar to those in Equations 2-27 through 2-31 and 2-35 through 2-39. Timoshenko (1941) stated that the solution for the “long” pile is satisfactory where L is greater than 4; however, there are occasions when the solution of the reduced differential equation is desired for piles that have a nondimensional length less than 4. The solution can be obtained by using the following boundary conditions at the tip of the pile. At x = L, d2y 0 (bending moment, M, is zero at pile tip)............................(2-44) dx 2 and d3y 0 (shear force, V, is zero at pile tip) .................................(2-45) dx3 When the above boundary conditions are used, along with a set for the top of the pile, the four coefficients C1, C2, C3, and C4 can be evaluated. The solutions are not shown here, but new values of the parameters A1, B1, C1, and D1 can be computed as a function of L. Such computations, if carried out, will show readily the influence of the length of the pile. 39 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading The reduced form of the differential equation will not normally be used for the solution of problems encountered in design; however, the influence of pile length and other parameters can be illustrated with clarity. Furthermore, the closed-form solution can be used to check the accuracy of the numerical solution shown in the next section. 2-2-3 Solution by Finite Difference Equations The solution of Equation 2-7 is necessary for dealing with numerous problems that are encountered in practice. The formulation of the differential equation in finite difference form and a solution by iteration mandates a computer program. In addition, the following improvements in the solutions shown in the previous section are then possible. The effect of the axial load on deflection and bending moment can be considered and problems of pile buckling can be solved. The bending stiffness EI of the pile can be varied along the length of the pile. Perhaps of more importance, the soil modulus Es can vary with pile deflection and with the depth of the soil profile. Soil displacements around the pile due to slope movements, seepage forces, or other causes can be taken into account. In the finite difference formulations, the derivative terms are replaced by algebraic expressions. The following central difference expressions have errors proportional to the square of the increment length h. dy ym 1 ym 1 dx 2h d 2 y ym 1 2 ym ym 1 dx 2 h2 d 3 y ym 2 2 ym 1 2 ym 1 ym 2 dx3 2h 3 d 4 y ym 2 4 ym 1 6 ym 4 ym 1 ym 2 dx 4 h4 If the pile is subdivided in increments of length h, as shown in Figure 2-19, the governing differential equation, Equation 2-7, in difference form with collected terms for y is as follows: y m 2 Rm 1 y m 1 (2 Rm 1 2 Rm Px Qh 2 ) y m ( Rm 1 4 Rm Rm 1 2 Px h 2 k m hH 4 ) .................................(2-46) y m 1 (2 Rm 2 Rm 1 Px h 2 ) y m 2 Rm 1Wh 4 0 40 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading y ym+2 h h ym+1 ym h ym-1 h ym-2 x Figure 2-19 Representation of deflected pile where Rm = EmIm (flexural rigidity of pile at point m) and km = Esm. The assumption is implicit in Equation 2-46 that the magnitude of Px is constant with depth. Of course, that assumption is not strictly true. However, experience has shown that the maximum bending moment usually occurs a relatively short distance below the ground line at a point where the value of Px is undiminished. This fact plus the fact that Px, except in cases of buckling, has little influence on the magnitudes of deflection and bending moment, leads to the conclusion that the assumption of a constant Px is generally valid. For the reasons given, it is thought to be unnecessary to vary Px in Equation 2-46; thus, a table of values of Px as a function of x is not required. If the pile is divided into n increments, n+1 equations of the sort as Equation 2-46 can be written. There will be n+5 unknowns because two imaginary points will be introduced above the top of the pile and two will be introduced below the bottom of the pile. If two equations giving boundary conditions are written at the bottom and two at the top, there will be n+5 equations to solve simultaneously for the n+5 unknowns. The set of algebraic equations can be solved by matrix methods in any convenient way. The two boundary conditions that are employed at the bottom of the pile involve the moment and the shear. If the possible existence of an eccentric axial load that could produce a moment at the bottom of the pile is discounted, the moment at the bottom of the pile is zero. The assumption of a zero moment is believed to produce no error in all cases except for short rigid piles that carry their loads in end bearing, and when the end bearing is applied eccentrically. (The case where the moment at the bottom of a pile is not equal to zero is unusual and is not treated by the procedure presented herein.) Thus, the boundary equation for zero moment at the bottom of the pile requires 41 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading y1 2 y0 y1 0 .....................................................(2-47) where y0 denotes the lateral deflection at the bottom of the pile. Equation 2-47 is expressing the condition that EI(d2y/dx2) = 0 at x = L (The numbering of the increments along the pile starts with zero at the bottom for convenience). The second boundary condition involves the shear force at the bottom of the pile. The assumption is made that soil resistance due to shearing stress can develop at the bottom of a short pile as deflection occurs. It is further assumed that information can be developed that will allow V0, the shear at the bottom of the pile, to be known as a function of y0 Thus, the second equation for the zero-shear boundary condition at the bottom of the pile is R0 y 2 2 y 1 2 y1 y 2 Px y 1 y1 V0 ..............................(2-48) 3 2h 2h Equation 2-48 is expressing the condition that there is some shear at the bottom of the pile or that EI(d3y/dx3) + Px (dy/dx) = V0 at x = L. The assumption is made in the equations that the pile carries its axial load in end bearing only, an assumption that is probably satisfactory for short piles for which V0 would be important. The value of V0 should be set equal to zero for long piles (2 or more points of zero deflection along the length of the pile). As noted earlier, two boundary equations are needed at the top of the pile. Four sets of boundary conditions, each with two equations, have been programmed. The engineer can select the set that fits the physical problem. Case 1 of the boundary conditions at the top of the pile is illustrated graphically in Fig 220. (The axial load Px is not shown in the sketches, but Px is assumed to act at the top of the pile for each of the four cases of boundary conditions.). For the condition where the shear at the top of the pile is equal to Pt, the following difference equation is employed. Vt +M +V yt+2 yt+1 yt yt-1 yt-2 h Figure 2-20 Case 1 of Boundary Conditions Vt Rt yt 2 2 yt 1 2 yt 1 yt 2 Px yt 1 yt 1 .........................(2-49) 3 2h 2h 42 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading For the condition where the moment at the top of the pile is equal to Mt, the following difference equation is employed. Mt Rt h2 y t 1 2 y t y t 1 .............................................(2-50) Case 2 of the boundary conditions at the top of the pile is illustrated graphically in Figure 2-21. Here the pile is embedded into a concrete pile cap for which the rotation is known. Often the rotation can be assumed as zero, at least for the initial trial analyses. Equation 2-49 is the first of the two needed equations. The second needed equation is for the condition where the slope St at the top of the pile is known. yt+2 yt+1 yt +Vt St yt-1 yt-2 1 Figure 2-21 Case 2 of Boundary Conditions St yt 1 yt 1 .......................................................(2-51) 2h Case 3 of the boundary conditions at the top of the pile is illustrated in Figure 2-22. It is assumed that the pile continues into a superstructure and is a member in a frame. The solution for this problem can proceed by cutting a free body at the bottom joint of the frame. A moment is applied to the frame at that joint, and the rotation of the frame is computed (or estimated for the initial trial analysis). The moment divided by the rotation, Mt /St, is the rotational stiffness provided by the superstructure and becomes one of the boundary conditions. To implement the boundary conditions in Case 3, it may be necessary to perform an initial solution for the pile, with an estimate of Mt /St, to obtain a preliminary value of the moment at the bottom joint of the superstructure. The superstructure can then be analyzed for a more accurate value of Mt /St, and then the pile can be re-analyzed. One or two iterations of this sort should be sufficient in most instances. 43 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Pile extends above ground surface and in effect becomes a column in the superstructure yt+2 yt+1 yt +Vt yt-1 h yt-2 Figure 2-22 Case 3 of Boundary Conditions Equation 2-49 is the first of the two equations that are needed for Case 3. The second equation expresses the condition that the rotational restraint Mt /St is known. Rt y 2 yt yt 1 M t h 2 t 1 ..............................................(2-52) yt 1 yt 1 St 2h Case 4 of the boundary conditions at the top of the pile is illustrated in Figure 2-23. It is assumed, for example, that a pile is embedded in a bridge abutment that moves laterally a given amount; thus, the deflection yt at the top of the pile is known. It is further assumed that the bending moment is known. If the embedment amount is small, the bending moment is frequently assumed as zero. The first of the two equations expresses the condition that the moment Mt at the pile head is known, and Equation 2-50 can be employed. The second equation merely expresses the fact that the pile-head deflection is known. yt Yt .............................................................(2-53) Case 5 of the boundary conditions at the top of the pile is illustrated in Figure 2-24. Both the deflection yt the rotation St at the top of the pile are assumed to be known. This case is related to the analysis of a superstructure because advanced models for structural analyses have been recently developed to achieve compatibility between the superstructure and the foundation. The boundary conditions in Case 5 can be conveniently used for computing the forces at the pile head in the model for the superstructure. Equation 2-53 can be used with a known value of yt and Equation 2-51 can be used with a known value of St. 44 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading Foundation moves laterally yt+2 Mt yt+1 yt yt-1 Pile-head moment is known, may be zero h yt-2 Figure 2-23 Case 4 of Boundary Conditions St yt yt+2 yt+1 yt 1 yt-1 yt-2 St Figure 2-24 Case 5 of Boundary Conditions The five boundary conditions at the top of a pile should be adequate for virtually any situation but other cases can arise. However, the boundary conditions that are available in LPile, with a small amount of effort, can produce the required solutions. For example, it can be assumed that Vt and yt are known at the top of a pile and constitute the required boundary conditions (not one of the four cases). The Case 4 equations can be employed with a few values of Mt being selected, along with the given value of yt. The computer output will yield values of Vt. A simple plot will yield the required value of Mt that will produce the given boundary condition, Vt. LPile solves the difference equations for the response of a pile to lateral loading. Solutions of some example problems are presented in the User’s Manual for LPile. In addition, case studies are included in which the results from computer solutions are compared with experimental results. Because of the obvious approximations that are inherent in the difference45 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading equation method, a discussion is provided of techniques for the verification of the accuracy of a solution that is essential to the proper use of the numerical method. The discussion will deal with the number of significant digits to be used in the internal computations and with the selection of the increment length h. However, at this point some brief discussion is in order about another approximation in Equation 2-46. The bending stiffness EI, denoted by R in the difference equations, is correctly represented as a constant in the second-order differential equation, Equation 2.-9. EI d2y M ...........................................................(2-9) dx 2 In finite difference form, Equation 2.9 becomes Rm ym 1 2 ym ym 1 M m ............................................. (2.54) h2 In building up the higher ordered terms by differentiation, the value of R is made to correspond to the central term for y in the second-order expression. The errors that are involved in using the above approximation where there is a change in the bending stiffness along the length of a pile are thought to be small, but may be investigated as necessary. 46 Chapter 2 – Solution for Pile Response to Lateral Loading (This page was deliberately left blank) 47 Chapter 3 Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-1 Introduction This chapter presents the formulation of expressions for p-y curves for soil and rock under both static and cyclic loading. As part of this presentation, a number of fundamental concepts are presented that are relevant to any method of analyzing deep foundations under lateral loading. Chapter 1 presented the concept of the p-y method, and this chapter will present details for the computation of load-transfer behavior for a pile under a variety of conditions. A typical p-y curve is shown in Figure 3-1a. The p-y curve is just one of a family of p-y curves that describe the lateral-load transfer along the pile as a function of depth and of lateral deflection. It would be desirable if soil reaction could be found analytically at any depth below the ground surface and for any value of pile deflection. Factors that might be considered are pile geometry, soil properties, and whether the type of loading, static is cyclic, sustained, or dynamic. Unfortunately, common methods of analysis are currently inadequate for solving all possible problems. However, principles of geotechnical engineering can be helpful in gaining insight into the evaluation of two characteristic portions of a p-y curve. Soil Resistance, p b b p c a a d Pile Deflection, y y (b) (a) b p a e y (c) Figure 3-1 Conceptual p-y Curves 49 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The p-y curve in Figure 3-1(a) is meant to represent the case where a short-term monotonic loading was applied to a pile. This case will be called “static” loading for convenience and will seldom, if ever, be encountered in practice. However, the static loading curve is useful because analytical procedures can be used to develop expressions to correlate with some portions of the curve, and the static curve serves as a baseline for demonstrating the effects of other types of loading. The three curves in Figure 3-1 show a straight-line relationship between p and y from the origin to point a. If it can be reasonably assumed that for small strains in soil there is a linear relationship between p and y for small values of y. Analytical methods for computing the slopes of the initial portion of the p-y curves, Esi, are discussed later. Recommendations will be given in this chapter for the selection of the slope of the initial portion of p-y curves for the various cases of soils and loadings that are addressed. The point should be made, however, that the recommendations for the slope of the initial portion are meant to be somewhat conservative because the deflection and bending moment of a pile under light loads will probably be somewhat less than computed by use of the recommendations. There are some cases in the design of piles under lateral loading when it will be unconservative to compute more deflection than will actually occur; in such cases, a field load test must be made. The portion of the curve in Figure 3-1(a) from points a to b shows that the value of p is strain softening with respect to y. This behavior is reflecting the nonlinear portion of the stressstrain curve for natural soil. Currently, there are no accepted analytical procedures that can be used to compute the a-b portion of a p-y curve. Rather, that portion of the curves is empirical and based on results of full-scale tests of piles in a variety of soils with both monotonic and cyclic loading. The horizontal, straight-line portion of the p-y curve in Figure 3-1(a) implies that the soil is behaving plastically with no loss of shear strength with increasing strain. Using this assumption, some analytical models can be used to compute the ultimate resistance pu as a function of pile dimensions, soil properties, and depth below the ground surface. One part of a model is for soil resistance near the ground surface and assumes that at failure the soil mass moves vertically and horizontally. The other part of the model is for the soil resistance deep below the ground surface and assumes only horizontal movement of the soil mass around the pile. Figure 3-1(b) shows a shaded portion of the curve in Figure 3-1(a). The decreasing values of p from point c to point d reflect the effects of cyclic loading. The curves in Figures 3-1(a) and 3-1(b) are identical up to point c, which implies that the soil behaves identically for both type of loading at small deflections. The loss of resistance shown by the shaded area depends on the number of cycles of loading. A possible effect of sustained, long-term loading is shown in Figure 3-1(c). This figure shows that there is a time-dependent increase in deflection with sustained loading. The decreasing value of p implies that the resistance is shifted to other elements of soil along the pile as the deflection occurs at some particular point. The effect of sustained loading should be negligible for heavily overconsolidated clays and for granular soils. The effect for soft clays must be approximated at present. 50 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-2 Experimental Measurements of p-y Curves Methods of getting p-y curves from field experiments with full-sized piles will be presented prior to discussing the use of analysis in getting soil response. The strategy that has been employed for obtaining design criteria is to make use of theoretical methods, to obtain p-y curves from full-scale field experiments, and to derive such empirical factors as necessary so that there is close agreement between results from adjusted theoretical solutions and those from experiments. Thus, an important procedure is obtaining experimental p-y curves. 3-2-1 Direct Measurement of Soil Response A number of attempts have been made to make direct measurements in the field of p and y. Measurement of lateral deflection involves the conceptually simple process using a slope inclinometer system to measure lateral deflection along the length of the pile. The method is cumbersome in practice and has not been very successful in the majority of tests in which it was attempted. Measurement of soil resistance directly involves the design of an instrument that will integrate the soil stress around the circumference at a point along the pile. The design of such an instrument has been proposed, but none has yet been built. Some attempts have been made to measure total soil stress and pore water pressure at a few points around the exterior of a pile with the view that the soil pressures at other points on the circumference can be estimated by interpolation. The method has met with little success for a variety of reasons, including changes in calibration when axial loads are applied to the pile and failure to survive pile installation. The experimental method that has met with the greatest success is to instrument the pile to measure bending strains along the length of the pile, typically using spacing of 6 to 12 inches (150 to 300 mm) between levels of gages. The data reduction consists of converting the strain measurements to bending curvature and bending moment, the obtaining lateral load-transfer than double differentiation of the bending moment curve versus depth, and obtaining lateral deflection by double integration of the bending curvature curve versus depth. 3-2-2 Derivation of Soil Response from Moment Curves Obtained by Experiment Almost all successful load test experiments that have yielded p-y curves have measured bending moment using electrical-resistance strain gages. In this method, curvature of the pile is measured directly using strain gages. Bending moment in the pile is computed from the product of curvature and the bending stiffness. Pile deflection can be obtained with considerable accuracy by twice integrating curvature versus depth. The deflection and the slope of the pile at the ground line are measured accurately. It is best if the pile is long enough so that there are at least two points of zero deflection along the lower portion of the pile so that it can be reasonably assumed that both moment and shear equal zero at the pile tip. Evaluation of soil resistance mobilized along the length of the pile requires two differentiations of a bending moment curve versus depth. Matlock (1970) made extremely accurate measurements of bending moment and was able to do the differentiations numerically (Matlock and Ripperger, 1958). This was possible by using a large number of gages and by calibrating the instrumented pile in the laboratory prior to installation in the field. However, most investigators fit analytical curves of various types through the points of experimental bending moment and mathematically differentiate the fitted curves. 51 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The experimental p-y curves can be plotted once multiple of curves showing the distribution of deflection and soil resistance for multiple levels of loading have been developed. A check can be made of the accuracy of the analyses by using the experimental p-y curves to compute bending-moment curves versus depth. The computed bending moments should agree closely with those measured in the load test. In addition, computed values of pile-head slope and deflection can be compared to the values measured during the load test. Usually, it is more difficult to obtain agreement between computations and measurement of pile-head deflection and slope over the full range of loading than for bending moment. Examples of p-y curves that were obtained from a full-scale experiment with pipe piles with a diameter of 641 mm (24 in.) and a penetration of 15.2 m (50 ft) are shown in Figures 3-2 and 3-3 (Reese et al., 1975) . The piles were instrumented for measurement of bending moment at close spacing along the length and were tested in overconsolidated clay. 3,000 x = 12" x = 24" x = 36" 2,500 x = 48" x = 60" Soil Resistance, p, lb/in. x = 72" x = 96" 2,000 x = 120" 1,500 1,000 500 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 Deflection, y, inches Figure 3-2 p-y Curves from Static Load Test on 24-inch Diameter Pile (Reese, et al. 1975) 52 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3,000 x = 12" x = 24" x = 36" x = 48" x = 60" x = 72" Soil Resistance, p, lb/in. 2,500 x = 84" x = 96" x = 108" x = 120" 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 Deflection, y, inches Figure 3-3 p-y Curves from Cyclic Load Test on 24-inch Diameter Pile (Reese, et al. 1975) 3-2-3 Nondimensional Methods for Obtaining Soil Response Reese and Cox (1968) described a method for obtaining p-y curves for cases where only pile-head measurements are made during lateral loading. They noted that nondimensional curves could be obtained for many variations of soil modulus with depth. Equations for the soil modulus involving two parameters were employed, such as shown in Equations 3-1 and 3-2. Es k1 k 2 x ..........................................................(3-1) or Es kxn .............................................................(3-2) Measurements of shear force, bending moment, pile-head deflection, and rotation at the ground line are necessary. Then, either of the equations is selected to develop expressions for 53 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock pile-head deflection and rotation in terms of Es and the two parameters (either k1 and k2 or k and n) are solved for a given applied load and moment. With an expression for soil modulus for a particular load, the soil resistance and deflection along the length of the pile can be then computed. The reader is referred to Reese and Cox (1968) for additional details. The procedure is repeated for each of the applied loadings. While the method is approximate, the p-y curves computed in this fashion do reflect the measured behavior of the pile head. Soil response derived from a sizable number of such experiments can add significantly to the existing information. As previously indicated, the major field experiments that have led to the development of the current criteria for p-y curves have involved the acquisition of experimental moment curves. However, nondimensional methods of analyses, as indicated above, have assisted in the development of p-y curves in some instances. In the remaining portion of this chapter, procedures are presented for developing p-y curves for clays and for sands. In addition, some discussion is presented for producing p-y curves for other types of soil. 3-3 p-y Curves for Cohesive Soils 3-3-1 Initial Slope of Curves The conceptual p-y curves in Figure 3-1 are characterized by an initial straight line from the origin to point a. A mass of soil with an assumed linear relationship between compressive stress and strain, Ei, for small strains can be considered. If a pile is caused to deflect a small distance in such a soil, one can reasonably assume that principles of mechanics can be used to find the initial slope Esi of the p-y curve. However, some difficulties are encountered in making the computations. For instance, the value of Ei for soil is not easily determined. Stress-strain curves from unconfined compression tests were studied (see Figure 3-4) and it was found that the initial modulus Ei ranged from about 40 to about 200 times the undrained shear strength c (Matlock, et al., 1956; Reese, et al., 1968). There is a considerable amount of scatter in the ratio values. This is probably due to the variability of the soils at the two sites that were studied. The ratios of Ei to c would probably have been higher had an attempt been made to get precise values for the early part of the curve. Stokoe (1989) reported that values of Ei in the order of 2,000 times c are found routinely in resonant column tests when soil specimens are subjected to shearing strains below 0.01 percent. Johnson (1982) performed some tests with the self-boring pressuremeter and computations with his results gave ratios of Ei to c that ranged from 1,440 to 2,840, with the average of 1,990. These studies of the initial modulus from compressive-stress-strain curves of clay seem to indicate that such curves are linear only over a limited range of strains. If the assumption is made that a program of subsurface investigation and laboratory testing can be used to obtain values of EI, the following equation for a beam of infinite length (Vesić, 1961) can be used to gain some information on the subgrade modulus (initial slope of the p-y curve): 54 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 4 0.65 Ei b E si b EpI p 1 / 12 Ei ...........................................(3-3) 2 1 Ei /c 0 100 200 300 0 Manor Road Lake Austin Depth, m 3 6 9 12 Figure 3-4 Plot of Ratio of Initial Modulus to Undrained Shear Strength for Unconfined-compression Tests on Clay Where: b = pile diameter, Ei = initial slope of stress-strain curve of soil, Ep = modulus of elasticity of the pile, and Ip = moment of inertia of pile, respectively, and = Poisson’s ratio. While Equation 3-3 may appear to provide some useful information on the initial slope of the p-y curves (the initial modulus of the soil in the p-y relationship), an examination of the initial slopes of the p-y curves in Figures 3-2 and 3-3 clearly show that the initial slopes are strongly influenced by depth below the ground surface. The initial slopes of those curves are plotted in Figure 3-5 and the influence of depth below the ground surface is apparent. Yegian and Wright (1973) and Thompson (1977) conducted some numerical studies using two-dimensional finite element analyses. The plane-stress case was employed in these studies to reflect the influence of the ground surface. Kooijman (1989) and Brown, et al. (1989) 55 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock used three-dimensional finite element analyses as a means of developing p-y curves. In addition to developing the soil response for small deflections of a pile, all of the above investigators used nonlinear elements in an attempt to gain information on the full range of soil response. Initial Soil Modulus, Esi, MPa 0 200 400 600 800 0 Pile 1 Static Depth, meters 0.6 1.2 1.8 2.4 Pile 2 (Cyclic) 3.0 Figure 3-5 Variation of Initial Modulus with Depth Studies using finite element modeling have found the finite element method to be a powerful tool that can supplement field-load tests as a means of producing p-y curves for different pile dimensions, or perhaps can be used in lieu of load tests on instrumented piles if the nonlinear behavior of the soil is well defined. However, some other problems may arise that are unique to finite element analysis: selecting special interface elements, modeling the gapping when the pile moves away from a clay soil (or the collapse of sand against the back of a pile), modeling finite deformations when soil moves up at the ground surface, and modeling tensile stresses during the iterations. Further development of general-purpose finite element software and continuing improvements in computing hardware are likely to increase the use of the finite element method in the future. 3-3-2 Analytical Solutions for Ultimate Lateral Resistance Two analyses are used to gain some insight into the ultimate lateral resistance pu that develop near the ground surface in one case and at depth in the other case. The first analysis is 56 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock for values of ultimate lateral resistance near the ground surface and considers the resistance a passive wedge of soil displaced by the pile. The second analysis is for values of lateral resistance well beneath the ground surface and models the plane-strain (flow-around) behavior of the soil. The first analytical model for clay near the ground surface is shown in Figure 3-6. Some justification can be presented for making use of a model that assumes that the ground surface will move upward. Contours of the measured rise of the ground surface during a lateral load test are shown in Figure 3-7. The p-y curves for the overconsolidated clay in which the pile was tested are shown in Figures 3-3 and 3-4. As shown in Figure 3-7(a) for a load of 596 kN (134 kips), the ground-surface moved upward out to a distance of about 4 meters (13 ft) from the axis of the pile. After the load was removed from the pile, the ground surface subsided to the profile as shown in Figure 3-7 (b). y Ft Ft W Ff x H Ft Fn Fp Fs Ff W Fp Fn Fs b (a) (b) Figure 3-6 Assumed Passive Wedge Failure in Clay Soils, (a) Shape of Wedge, (b) Forces Acting on Wedge The use of plane sliding surfaces, shown in Figure 3-6, will obviously not model the movement that is indicated by the contours in Figure 3-7; however, a solution with the simplified model should give some insight into the variation of the ultimate lateral resistance pu with depth. Summing the forces in the vertical direction yields Fn sin W Fs cos 2Ft cos F f .....................................(3-4) where = angle of the inclined plane with the vertical, and W = the weight of the wedge. 57 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The expression for W is bH 2 W tan ........................................................(3-5) 2 25 mm 19 mm 3 mm 6 mm 596 kN 13 mm (a) Heave at maximum load 3 mm 0 kN 13 mm 6 mm (b) Residual heave 4 3 2 1 0 Scale, meters Figure 3-7 Measured Profiles of Ground Surface Heave Near Piles Due to Static Loading, (a) Ground Surface Heave at Maximum Load, (b) Residual Ground Surface Heave where: = unit weight of soil, b = width (diameter) of pile, and H = depth of wedge. The resultant shear force on the inclined plane Fs is Fs ca bH sec ........................................................(3-6) 58 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock where ca is the average undrained shear strength of the clay over depth H. The resultant shear force on a side plane is Ft ca H 2 tan ........................................................(3-7) 2 The frictional force between the wedge and the pile is Ft ca bH ...........................................................(3-8) where is a reduction factor. The above equations are solved for Fp, and Fp is differentiated with respect to H to solve for the soil resistance pc1 per unit length of the pile. pc1 ca btan (1 ) cot bH 2ca H (tan sin cos ) .................(3-9) The value of can be set to zero with some logic for the case of cyclic loading because one can reason that the relative movement between pile and soil would be small under repeated loads. The value of can be taken as 45 degrees, if the soil is assumed to behave in an undrained mode. With these assumptions, Equation 3-9 becomes pc1 2ca b bH 2.83ca H ............................................(3-10) However, Thompson (1977) differentiated Equation 3-9 with respect to H and evaluated the integrals numerically. His results are shown in Figure 3-8 with the assumption that the value of the term /ca is negligible. The cases where is assumed as zero and where is assumed 1.0 are shown in the figure. Also shown in Figure 3-8 is a plot of Equation 3-10 with the same assumption with respect to /ca. As shown, the differences in the plots are not great. The curve in Figure 3-8 from Hansen (1961a, 1961b), indicated by the blue line, is discussed on page 72. The equations developed above do not address the case of tension in the pile. If piles are designed for a permanent uplift force, the equation for ultimate soil resistance should be modified to reflect the effect of an uplift force at the face of the pile (Darr, et al., 1990). The second of the two models for computing the ultimate resistance pu is shown in the plan view in Figure 3-9(a). At some point below the ground surface, the maximum value of soil resistance will occur with the soil moving horizontally. Movement in only one side of the pile is indicated; but movement, of course, will be around both sides of the pile. Again, planes are assumed for the sliding surfaces with the acceptance of some approximation in the results. A cylindrical pile is indicated in the figure, but for ease in computation, a prismatic block of soil is subjected to horizontal movement. Block 5 is moved laterally as shown and stress of sufficient magnitude is generated in that block to cause failure. Stress is transmitted to Block 4 and on around the pile to Block 1, with the assumed movements indicated by the dotted lines. Block 3 is assumed not to distort, but failure stresses develop on the sides of the block as it slides. 59 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock pu cb 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 0 0 2 = 1.0 (Thompson) pc1 2ca b bH 2.83ca H 4 H b =0 (Thompson) 6 8 pu cb 2.567 5.307 1 0.652 H b H b 10 Figure 3-8 Ultimate Lateral Resistance for Clay Soils The Mohr-Coulomb diagram for undrained, saturated clay is shown in Figure 3-9(b) and a free body of the pile is shown in Figure 3-9(c). The ultimate soil resistance pc2 is independent of the value of 1 because the difference in the stress on the front 6 and back 1 of the pile is equal to 10c. The shape of the cross section of a pile will have some influence on the magnitude of pc2; for the circular cross section, it is assumed that the resistance that is developed on each side of the pile is equal to c (b/2), and pc 2 6 1 c b 11c b ............................................(3-11) Equation 3-11 is also shown plotted in Figure 3-8. Thompson (1977) noted that Hansen (1961a, 1961b) formulated equations for computing the ultimate resistance against a pile at the ground surface, at a moderate depth, and at a great depth. Hansen considered the roughness of the wall of the pile, the angle of internal friction, and unit weight of the soil. He suggested that the influence of the unit weight be neglected and proposed the following equation for the equals zero case for all depths. 60 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 5 2 c 4 5 6 3 1 1 1 c 5 6 5 2 4 3 3 4 Pile Movement 2 (a) c 2c (b) cb/2 6b 1b pu cb/2 (c) Figure 3-9 Assumed Mode of Soil Failure Around Pile in Clay, (a) Section Through Pile, (b) Mohr-Coulomb Diagram, (c) Forces Acting on Section of Pile pu cb 2.567 5.307 1 0.652 H b H b .................................................(3-12) Equation 3-12 is also shown plotted in Figure 3-8. The agreement with the “block” solutions is satisfactory near the ground surface, but the difference becomes significant with depth. 61 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Equations 3-10 and 3-11 are similar to Equations 3-20 and 3-21, presented later, that are used in the recommendations for two of the models of p-y curves. However, emphasis was placed on experimental results. The values of pu obtained in the full-scale experiments were compared to the analytical values, and empirical factors were found by which Equations 3-10 and 3-11 could be modified. The adjustment factors that were determined are shown in Figure 310 (see Section 3-3-8 for more discussion), and it can be seen that the experimental values of ultimate resistance for overconsolidated clay below the water table were far smaller than the computed values. The recommended method of computing the p-y curves for such clays is presented later. Ac and As 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 0 2 Ac x b As 4 6 8 Figure 3-10 Values of Ac and As 3-3-3 Influence of Diameter on p-y Curves The analytical developments presented to this point indicate that the term for the pile diameter appears to the first power in the expressions for p-y curves. Reese, et al. (1975) described tests of piles with diameters of 152 mm (6 in.) and 641 mm (24 in.) at the Manor site. The p-y formulations developed from the results from the larger piles were used to analyze the behavior of the smaller piles. The computation of bending moment led to good agreement between analysis and experiment, but the computation of ground line deflection showed considerable disagreement, with the computed deflections being smaller than the measured ones. No explanation could be made to explain the disagreement. O’Neill and Dunnavant (1984) and Dunnavant and O’Neill (1985) reported on tests performed at a site where the clay was overconsolidated and where lateral-loading tests were 62 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock performed on piles with diameters of 273 mm (10.75 in.), 1,220 mm (48 in.), and 1,830 mm (72 in.). They found that the site-specific response of the soil could best be characterized by a nonlinear function of the diameter. There is good reason to believe that the diameter of the pile should not appear as a linear function when piles in clays below the water table are subjected to cyclic loading. However, data from experiments are insufficient at present to allow general recommendations to be made. The influence of cyclic loading on p-y curves is discussed in the next section. 3-3-4 Influence of Cyclic Loading Cyclic loading is specified in a number of the examples presented in Chapter 1; a notable example is an offshore platform. Therefore, a number of the field tests employing fully instrumented piles have employed cyclic loading in the experimental procedures. Cyclic loading has invariably resulted in increased deflection and bending moment above the respective values obtained in short-term loading. A dramatic example of the loss of soil resistance due to cyclic loading may be seen by comparing the two sets of p-y curves in Figures 3-2 and 3-3. Wang (1982) and Long (1984) did extensive studies of the influence of cyclic loading on p-y curves for clays. Some of the results of those studies were reported by Reese, et al. (1989). The following two reasons can be suggested for the reduction in soil resistance from cyclic loading: the subjection of the clay to repeated strains of large magnitude, and scour from the enforced flow of water near the pile. Long (1984) studied the first of these factors by performing some triaxial tests with repeated loading using specimens from sites where piles had been tested. The second of the effects is present when water is above the ground surface, and its influence can be severe. Welch and Reese (1972) report some experiments with a bored pile under repeated lateral loading in overconsolidated clay with no free water present. During the cyclic loading, the deflection of the pile at the ground line was in the order of 25 mm (1 in.). After a load was released, a gap was revealed at the face of the pile where the soil had been pushed back. In addition, cracks a few millimeters in width radiated away from the front of the pile. Had water covered the ground surface, it is evident that water would have penetrated the gap and the cracks. With the application of a load, the gap would have closed and the water carrying soil particles would have been forced to the ground surface. This process was dramatically revealed during the soil testing in overconsolidated clay at Manor (Reese, et al., 1975) and at Houston (O’Neill and Dunnavant, 1984) . The phenomenon of scour is illustrated in Figure 3-11. A gap has opened in the overconsolidated clay in front of the pile and it has filled with water as load is released. With the next cycle of loading on the pile, the water is forced upward from the space. The water exits from the gap with turbulence and the clay is eroded from around the pile. Wang (1982) constructed a laboratory device to investigate the scouring process. A specimen of undisturbed soil from the site of a pile test was brought to the laboratory, placed in a mold, and a vertical hole about 25 mm (1 in.) in diameter was cut in the specimen. A rod was carefully fitted into the hole and hinged at its base. Water a few millimeters deep was kept over the surface of the specimen and the rod was pushed and pulled by a machine at a given period and a given deflection for a measured period. The soil that was scoured to the surface of the specimen was carefully collected, dried, and weighed. The deflection was increased, and the 63 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock process was repeated. A curve was plotted showing the weight of soil that was removed as a function of the imposed deflection. The characteristics of the curve were used to define the scour potential of that particular clay. Boiling and turbulence as space closes (a) (b) Figure 3-11 Development of Scour Around Pile in Clay During Cyclic Loading, (a) Profile View, (b) Photograph of Turbulence Causing Erosion During Lateral Load Test The device developed by Wang was far more discriminating about scour potential of a clay than was the pinhole test (Sherard, et al., 1976), but the results of the test could not explain fully the differences in the loss of resistance experienced at different sites where lateral-load tests were performed in clay with water above the ground surface. At one site where the loss of resistance due to cyclic loading was relatively small, it was observed that the clay included some seams of sand. It was reasoned that the sand would not have been scoured readily and that particles of sand could have partially filled the space that was developed around the pile. In this respect, one experiment showed that pea gravel placed around a pile during cyclic loading was effective in restoring most of the loss of resistance. However, O’Neill and Dunnavant (1984) report that “placing concrete sand in the pile-soil gap formed during previous cyclic loading did not produce a significant regain in lateral pile-head stiffness. “ While both Long (1984) and Wang (1982) developed considerable information about the factors that influence the loss of resistance in clays under free water due to cyclic loading, their work did not produce a definitive method for predicting the loss of resistance. Thus, the analyst should be cautious when making use of the numerical results presented here with regard to the behavior of piles in clay under cyclic loading. Full-scale experiments with instrumented piles at a particular site are recommended for those cases where behavior under cyclic loading is a critical design requirement. 64 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-3-5 Introduction to Procedures for p-y Curves in Clays 3-3-5-1 Early Recommendations for p-y Curves in Clay Designers used all available information for selecting the sizes of piles to sustain lateral loading in the period prior to the advent of instrumentation that allowed the development of p-y curves from experiments with instrumented piles. The methods yielded values of soil modulus that were employed principally with closed-form solutions of the differential equation. The work of Skempton (1951) and the method proposed by Terzaghi (1955) were useful to the early designers. The method proposed by McClelland and Focht (1956), discussed later, appeared at the beginning of the period when large research projects were conducted. This model is significant because those authors were the first to present the concept of using p-y curves to model the resistance of soil against lateral pile movement. Their paper is based on a full-scale experiment at an offshore site where a moderate amount of instrumentation was employed. 3-3-5-2 Skempton (1951) Skempton (1951) stated that “simple theoretical considerations” were employed to develop a prediction model for load-settlement curves. The theory can be also used to obtain p-y curves if it is assumed that the ground surface does not affect the results, that the state of stress is the same in the horizontal and vertical directions, and that the stress-strain behavior of the soil is isotopic. The mean settlement, , of a foundation of width b on the surface of a semi-infinite elastic solid is given by Equation 3-13. qbI I 2 ......................................................(3-13) E where: q = foundation pressure, I = influence coefficient, = Poisson’s ratio of the solid, and E = Young’s modulus of the solid. In Equation 3-13, the value of Poisson’s ratio can be assumed to be 0.5 for saturated clays if there is no change in water content, and I can be taken as /4 for a rigid circular footing on the surface. Furthermore, for a rigid circular footing, the failure stress qf may be taken as equal 6.8 c, where c is the undrained shear strength. Making the substitutions indicated and setting = 1 for the particular case 1 b 4c q ..........................................................(3-14) E qf 65 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Skempton noted that the influence value I decreases with depth below the ground surface and the bearing capacity factor increases; therefore, as a first approximation Equation 3-14 is valid at any depth. In an undrained compression test, the axial strain is given by 1 3 E E ....................................................(3-15) Where E is Young’s modulus at the principal stress difference of 1 3 . For saturated clays with no change in water content, Equation 3-15 may be rewritten as 2c 1 3 .................................................... (3-16) E 1 3 f Where 1 3 f is the principal stress difference at failure. Equations 3-14 and 3-16 show that, for the same ratio of applied stress to ultimate stress, the strain in the footing test (or pile under lateral loading) is related to the strain in the laboratory compression test by the following equation. 1 b 2 The equation above can be rearranged as 1 2 b .......................................................... (3-17) Skempton’s reasoning was based on the theory of elasticity and on the actual behavior of full-scale foundations, led to the following conclusion: “Thus, to a degree of approximation (20 percent) comparable with the accuracy of the assumptions, it may be taken that Equation 3-17 applies to a circular or any rectangular footing.” Skempton stated that the failure stress for a footing reaches a maximum value of 9c. If one assumes the same value for a pile in saturated clay under lateral loading, pu becomes 9cb. A p-y curve could be obtained, then, by taking points from a laboratory stress-strain curve and using Equation 3-17 to obtain deflection and 4.5 b to obtain soil resistance. The procedure would presumably be valid at depths beyond where the presence of the ground surface would not reduce the soil resistance. Skempton presented information about laboratory stress-strain curves to indicate that 50, the strain corresponding to a stress of 50 percent of the ultimate stress, ranges from about 0.005 to 0.02. That information, and information about the general shape of a stress-strain curve, allows an approximate curve to be developed if only the strength of the soil is available. 66 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-3-5-3 Terzaghi (1955) In a widely referenced paper, Terzaghi discussed several important aspects of subgrade reaction, including the resistance of soil to lateral loading of a pile. Unfortunately, while his numerical recommendations reveal that his knowledge of the problem of the pile was extensive, Terzaghi did not present experimental data or analytical procedures to validate his recommendations. Terzaghi’s recommendations for the coefficient of subgrade reaction for piles in stiff clay were based on a concept that the deformational characteristics of stiff clay are “more or less independent of depth.” Consequently, he proposed that p-y curves should be constant with depth and that the ratio between p and y should be defined by a constant T. Therefore, his family of py curves (though not defined in such these terms) consisted of a series of straight lines, all with the same slope, and passing through the origin of the p-y coordinate system. Terzaghi recognized, of course, that the pile could not be deflected to an unlimited extent with a linear increase in soil resistance and that a lateral bearing capacity exists for laterally loaded piles. Terzaghi stated that the linear relationship between p and y was limited to values of p that were smaller than about one-half of the maximum lateral load-transfer capacity. Table 3-1 presents Terzaghi’s recommendations for stiff clay. The units have been changed to reflect current practice. These values of T are independent of pile diameter, which is consistent with theory for small deflections. Table 3-1 Terzaghi’s Recommendations for Soil Modulus for Laterally Loaded Piles in Stiff Clay (no longer recommended) Consistency of Clay Stiff Very Stiff Hard qu, kPa 100-200 200-400 > 400 qu, tsf 1-2 2-4 >4 Soil Modulus, T, MPa 3.2-6.4 6.4-12.8 > 12.8 Soil Modulus, T, psi 460-925 925-1,850 > 1,850 3-3-5-4 McClelland and Focht (1956) McClelland and Focht (1956) wrote the first paper that described the concept of nonlinear lateral load-transfer curves, now referred to as p-y curves. In this paper, they presented the first nonlinear p-y curves derived from a full-scale, instrumented, pile-load test. Significantly, this paper shows conclusively that lateral load transfer is a function of lateral pile deflection and depth below the ground surface, as well as of soil properties. McClelland and Focht recommended testing of soil using consolidated-undrained triaxial tests with the confining pressure set equal to the overburden pressure. The results of the shear test should be plotted as the compressive stress difference, , versus the axial compressive strain, . The p-values of the p-y curve are then scaled from the stress-strain curve using p 5.5 b ......................................................... (3-18) 67 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock and the values of pile deflection y are scaled using y 0.5 b .......................................................... (3-19) These equations are similar in form to those developed by Skempton, but the factors used for lateral defection are different (0.5 used by McClelland and Focht and 2 used by Skempton). 3-3-6 Procedures for Computing p-y Curves in Clay Five procedures are provided for computing p-y curves for clay. Each procedure is based on the analysis of the results of experiments using full-scale instrumented piles. In every case, a comprehensive soil investigation was performed at each load test site and the best estimate of the undrained shear strength of the clay was found. In addition, the physical dimensions and bending stiffness of the piles were accurately evaluated. Experimental p-y curves were obtained by one or more of the techniques described earlier. Euler-Bernoulli beam theory was used and mathematical expressions were developed for p-y curves for use in a computer analysis to obtain values of lateral pile deflection and bending moment versus depth that agreed well with the experimental values. Loadings in all load tests were both short-term (static) and cyclic. The p-y curves that resulted from the two tests performed with water above the ground surface have been used extensively in the design of offshore structures around the world. 3-3-7 Response of Soft Clay in the Presence of Free Water 3-3-7-1 Background Matlock (1970) performed lateral-load tests with an instrumented steel-pipe pile that was 324 mm (12.75 in.) in diameter and 12.8 meters (42 ft) long. The test pile was driven into clay near Lake Austin, Texas that had an average shear strength of about 38 kPa (800 psf). The test pile was exhumed after the first test and taken to Sabine Pass, Texas, and driven into soft clay with a shear strength that averaged about 14.4 kPa (300 psf) in the significant upper zone. The initial loading was short-term. The load was applied to the pile long enough for readings of strain gages to be taken by an extremely precise device. A rough balance of the external Wheatstone bridge was obtained by use of a precision decade box and the final balance was taken by rotating a 150-mm-diameter drum on which a copper wire had been wound. A contact on the copper wire was read on the calibrated drum when a final balance was achieved. The accuracy of the strain readings was less than one microstrain, but some time was required to obtain readings sequentially from the top of the pile to the bottom and back up to the top again. The pressure in the hydraulic ram that controlled the load was adjusted as necessary to maintain a constant load because of the creep of the soil under the imposed loading. The two sets of readings at each point along the pile were interpolated with time to find the value at a selected time, assuming that the change in moment due to creep had a constant rate. The accurate readings of bending moment allowed the soil resistance to be found by numerical differentiation, which was a distinct advantage. The disadvantage was the somewhat indeterminate influence of the creep of the soft clay. The test pile was extracted, re-driven, and tested a second type with cyclic loading. Readings of the strain gages were taken under constant load after specified numbers of cycles of 68 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock loading. The load was applied in two directions, with the load in the forward direction being more than twice as large as the load in the backward direction. After a significant number of cycles, the deflection at the top of the pile was either stable or creeping slowly, so an equilibrium condition was assumed. The p-y curves for cyclic loading are intended to represent a lowerbound condition. Thus, a designer might possibly be computing an overly conservative response of a pile, if the cyclic p-y curves are used and if there are only a small number of applications of the design load (the factored load). 3-3-7-2 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Soft Clay for Static Loading The following procedure is for short-term static loading and is illustrated by Figure 312(a). As noted earlier, the curves for static loading constitute the basis for indicating the influence of cyclic loading and would be rarely used in design if cyclic loading is of concern. 1. Obtain the best possible estimates of the variation of undrained shear strength c and effective unit weight with depth. Also, obtain the value of 50, the strain corresponding to one-half the maximum principal stress difference. If no stress-strain curves are available, typical values of 50 are given in Table 3-2. Table 3-2 Representative Values of 50 for Soft to Stiff Clays 2. Consistency of Clay 50 Soft 0.020 Medium 0.010 Stiff 0.005 Compute the ultimate soil resistance per unit length of pile, using the smaller of the values given by the equations below. avg J pu 3 x x cb .............................................. (3-20) c b pu 9 c b .......................................................... (3-21) where = average effective unit weight from ground surface to p-y curve,1 avg x = depth from the ground surface to p-y curve, c = shear strength at depth x, and b = width of pile. 1 Matlock did not specify in his original paper whether the unit weight was total unit weight or effective unit weight. However, API RP2A specifies that effective unit weight be used. Most users have adopted the recommendation by API and this is the implementation chosen for LPile. 69 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 1 1 p 0.5 pu 0 p y 3 0.5 pu y50 0 1 y y50 8.0 (a) p pu 1 For x xn (Depth where Flow AroundFailureGoverns 0.72 0.5 0.72 0 0 3 1 y y50 x xr 15 (b) Figure 3-12 p-y Curves in Soft Clay,(a) Static Loading, (b) Cyclic Loading Matlock (1970) stated that the value of J was determined experimentally to be 0.5 for soft clay and about 0.25 for a medium clay. A value of 0.5 is frequently used for J for offshore soils in the Gulf of Mexico. The value of pu is computed at each depth where a p-y curve is desired, based on shear strength at that depth. Equations 3-20 and 3-21 are solved simultaneously to find the transition depth, xr, where the transition in definition of pu by Equation 3-20 to 3-21 occurs. In general, the minimum value of xr should be 2.5 pile diameters (see API RP2A, 2010, Section 6.8.2). If the unit weight and shear strength are constant in the soil layer, then xr is computed using 70 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock xr 6cb 2.5 ................................................... (3-22) b Jc LPile has two versions of the soft clay criteria. One version uses a value of J equal to 0.5 by default. This is the version used by most users. The second version is identical in computations as the first, but the user may enter the value of J at the top and bottom of the soil layer. LPile does not perform error checking on the input value of J. If the p-y curve with variable J (API soft clay with user-defined J) is selected, the user should consider the advice by Matlock for selecting the J value discussed on page 82. The net effect of using a J value less than 0.5 is to reduce the strength of the p-y curve. An example of the effect of J on a p-y curve at a depth of 5 feet for a 36-inch diameter pile in soft clay with c = 1,000 psf and = 55 pcf is shown in Figure 3-13. 1,200 1,000 p, lbs/inch 800 600 400 J = 0.5 J = 0.25 200 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 y, inches Figure 3-13 Example p-y Curves in Soft Clay Showing Effect of J 3. Compute deflection at one-half the ultimate soil resistance, y50, from the following equation: y50 = 2.5 50b ....................................................... (3-23) 4. Compute points describing the p-y curve from the origin up to 8 y50 using 1 p p u 2 y ...................................................... (3-24) y 50 71 3 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The value of p remains constant for y values beyond 8 y50. 3-3-7-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Soft Clay for Cyclic Loading The following procedure is for cyclic loading and is illustrated in Figure 3-12(b). As noted earlier in this chapter, the presence of free water at the ground surface has a significant influence on the behavior of a pile in clay under cyclic loading. If the clay is soft, the assumption can be made that there is free water, otherwise the clay would have dried and become stiffer. A question arises whether or not to use these recommendations if a thin stratum of stiff clay is present above the soft clay and the water table is at the interface of the soft and the stiff clay. In such a case, free water is unlikely to be ejected to the ground surface and erosion around the pile due to scour would not occur. However, the free water in the excavation, under repeated excursions of the pile, could cause softening of the clay. Therefore, the following recommendations for p-y curves for cyclic loading can be used with the recognition that there may be some conservatism in the results. 1. Construct the p-y curve in the same manner as for short-term static loading for values of p less than 0.72pu. For lateral displacements in this range, there is not significant degradation of the p-y curve during cyclic loading. 2. If the depth to the p-y curve is greater than or equal to xr (Equation 3-22), select p as 0.72pu for y equal to 3y50 (Note that the number 0.72 is computed using Equation 3-24 as 1/2 * 31/3 = 0.721124785 ~ 0.72). 3. If the depth of the p-y curve is less than xr, note that the value of p decreases from 0.72pu at y = 3y50 down to the value given by Equation 3-25 at y = 15y50. x p 0.72 pu xr ..................................................... (3-25) The value of p remains constant beyond y = 15y50. 3-3-7-4 Recommended Soil Tests for Soft Clays For determining the various shear strengths of the soil required in the p-y construction, Matlock (1970) recommended the following tests in order of preference. 1. In-situ vane-shear tests with parallel sampling for soil identification, 2. Unconsolidated-undrained triaxial compression tests having a confining stress equal to the overburden pressure with c being defined as one-half the total maximum principalstress difference, 3. Miniature vane tests of samples in tubes, and 4. Unconfined compression tests. Tests must also be performed on the soil samples to determine the total unit weight of the soil, water content, and effective unit weight. 3-3-7-5 Examples An example set of p-y curves was computed for soft clay for a pile with a diameter of 610 mm (24 in.). The soil profile that was used is shown in Figure 3-14. The submerged unit weight was 6.3 kN/m3 (40 pcf). In the absence of a stress-strain curve for the soil, 50 was taken as 0.02 72 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock for the full depth of the soil profile. The loading was assumed to be static. The p-y curves were computed for the following depths below the ground surface: 1.5 m (5 ft), 3 m (10 ft), 6 m (20 ft), and 12 m (40 ft). The plotted curves are shown in Figure 3-15. 0 2 Depth, meters 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 0 10 20 30 40 50 Shear Strength, kPa Figure 3-14 Shear Strength Profile Used for Example p-y Curves for Soft Clay 250 Load Intensity p, kN/m 200 150 Depth = 2.00 m Depth = 3.00 m Depth = 6.00 m Depth = 12.00 m 100 50 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 Lateral Deflection y, meters Figure 3-15 Example p-y Curves for Soft Clay with the Presence of Free Water 73 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-3-8 Response of Stiff Clay in the Presence of Free Water 3-3-8-1 Background Reese, Cox, and Koop (1975) performed lateral-load tests with instrumented steel pipe piles that were 641 mm (24 in.) in diameter and 15.2 m (50 ft) long. The piles were driven into stiff clay at a site near Manor, Texas. The clay had an undrained shear strength ranging from about 96 kPa (1 tsf) at the ground surface to about 290 kPa (3 tsf) at a depth of 3.7 m (12 ft). The loading of the pile was applied in a similar manner to that described for the tests performed by Matlock (1970). A significant difference was that a data-acquisition system was employed that allowed a full set of readings of the strain gages to be taken in about a minute. Thus, the creep of the piles under sustained loading was small or negligible. The disadvantage of the system was that the accuracy of the curves of bending moment was such that curve fitting was necessary in doing the differentiations. As in the case of the Matlock recommendations for cyclic loading, the lower-bound pile response is presented. Cyclic loading was continued until the lateral pile deflection and bending moments appeared to stabilize. The number of cycles of loading was in the order of 100; and 500 cycles were applied later in a reloading test. O’Neill and Dunnavant (1984) reported that an equilibrium condition was not reached during cyclic loading of piles at the Houston site. It is likely that the same result would have been found at the Manor test site. However, the l00 cycles of loading that were applied at Manor at a load at which the pile was near its ultimate bending moment and the loading was more than would be expected during an offshore storm or under other types of repeated loading. The diameter appears to the first power in the equations for p-y curves for cyclic loading. However, based on lateral tests performed later on piles of larger diameter, there is reason to believe that a nonlinear relationship for diameter may be required for piles of greater diameter. During the load test with cyclic loading, an annular gap developed between the soil and the pile after deflection at the ground surface of perhaps 10 mm (0.4 in.) and scour of the soil at the face of the pile due to ejected water, as shown in Figure 3-11, began at that time. The open gap remained at the conclusion of the load test. A photograph showing the annular gap is shown in Figure 3-16. There is reason to believe that scour would be initiated in overconsolidated clays after a given deflection at the mudline rather than at a given fraction of the pile diameter, as indicated by the following recommendations. However, insufficient data are available at present to justify a change in the recommended procedures. However, engineers could recommend a field test at a particular site in recognition of some uncertainty regarding the influence of scour on p-y curves for overconsolidated clays. 3-3-8-2 Recommendations for Use A frequent question posed by engineers when selecting p-y criteria for stiff cohesive soils is “Under what conditions should the criteria for stiff clay in the presence of free water be used?” There is no definitive answer to this question, but general recommendations can be made to guide the user. 74 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Erosion Figure 3-16 Annular Gapping Developed Around Pile After Cyclic Loading The user of LPile should consider several factors, including the position and depth of the layer in the soil profile, access of free water to the stiff clay from the surface or adjacent or interbedded water-bearing sand layers, and the presence of fissuring in the clay. The position of the stiff clay in the soil profile is important. If the depth range of the stiff soil is in the upper portion is below a depth equal to 10 to 12 piles diameters below the ground surface, the lateral pile deflection is highly likely to be too small for an opening to develop around the pile. In this case, the p-y model for stiff clay without free water should be chosen. If the stiff clay layer is within the depth range of 10 to 12 pile diameters of the surface and inflow of free water is possible from surface water, a high water table, or water-bearing sand layers adjacent to the stiff clay. In such conditions, the development of an annulus around the pile due to erosion of soil from around the pile during cyclic loading is more likely to occur. In such conditions, the p-y model for stiff clay with free water should be chosen. If the soil is highly fissured and has access to free water, the presence of fissuring will contribute to the degradation of the lateral load-transfer from the pile to the soil. As such, the presence of fissuring should encourage the selection of the p-y model for stiff clay with free water. If the soil is not fissured and is largely intact and dense, the development of erosion from around the pile is much less likely. Another important factor to consider is the possible presence of a clean sand layer (i.e. sand without fines) above the stiff clay layer. If clean sand is present, it may be possible for some sand from the layers above to fill any gap that develops around the pile in the stiff clay layer, 75 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock thereby counter-acting some of the negative effects of erosion. If this condition is present, a reasonable choice would be to select the p-y model for stiff clay without free water. 3-3-8-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves for Static Loading The following procedure is for computing p-y curves in stiff clay with free water for short-term static loading and is illustrated by Figure 3-17. As before, these curves form the basis for evaluating the effect of cyclic loading, and they may be used for sustained loading in some circumstances. 1. Obtain values of undrained shear strength c, effective unit weight , and pile diameter b at depth x. 2. Compute the average undrained shear strength ca over the depth x. 3. Compute the soil resistance per unit length of pile, pc, using the smaller value of pct or pcd computed using Equations 3-26 and 3-27. pct 2ca b bx 2.83ca x ............................................ (3-26) pcd 11cb ........................................................ (3-27) 4. Choose the appropriate value of As from Figure 3-10 on page 74 for modifying pct and pcd and for shaping the p-y curves or compute As as a function of x/b using As 0.2 0.4 tanh0.62 x / b ............................................ (3-28) p p pc 2 y y50 1.25 y As y50 poffset 0.055 pc A y s 50 0.5pc Ess y50 50b 0.0625 pc y50 Esi k s x 0 y50 As y50 6y50 18y50 y Figure 3-17 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Static Loading in Stiff Clay with Free Water 76 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 5. Establish the initial linear portion of the p-y curve, using the appropriate value of ks for static loading or kc for cyclic loading from Table 3-3 for k. p (kx) y ......................................................... (3-29) Table 3-3 Representative Values of k for Stiff Clays Average Undrained Shear Strength* ks (static loading) kc (cyclic loading) 50-100 kPa (1,000-2,000 psf) 135 MN/m3 (500 pci) 55 MN/m3 (200 pci) 100-200 kPa (2,000-4,000 psf) 270 MN/m3 (1,000 pci) 110 MN/m3 (400 pci) 200-400 kPa (4,000-6,000 psf) 540 MN/m3 (2,000 pci) 220 MN/m3 (800 pci) *The average shear strength should be computed as the average of shear strength of the soil from the ground surface to a depth of 5 pile diameters. It should be defined as one-half the maximum principal stress difference in an unconsolidatedundrained triaxial test. Note: Conversions of stress ranges are approximate in this table. 6. Compute y50 as y50 50b .......................................................... (3-30) using an appropriate value of 50 from results of laboratory tests or, in the absence of laboratory tests, from Table 3-4. Note that the strain values of 50 are dimensionless. Table 3-4 Representative Values of 50 for Stiff to Hard Clays 7. Average Undrained Shear Strength 50 50-100 kPa (1,000-2,000 psf) 0.007 100-200 kPa (2,000-4,000 psf) 0.005 200-400 kPa (4,000-6,000 psf) 0.004 Compute the first parabolic portion of the p-y curve using the following equation. The value of pc is computed using the smaller of the two values computed using Equations 326 for shallow wedge failure conditions or Equation 3-27 for deep flow-around failure conditions. 77 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock y p 0.5 pc y 50 0.5 .................................................... (3-31) Equation 3-31 should define the portion of the p-y curve from the point of the intersection with Equation 3-29 to a point where y is equal to Asy50 (see note in Step 10). 8. Establish the second parabolic portion of the p-y curve, y p 0.5 pc y50 0.5 y As y50 0.055 pc As y50 1.25 ............................... (3-32) Equation 3-32 should define the portion of the p-y curve from the point where y is equal to Asy50 to a point where y is equal to 6Asy50 (see note in Step 10). 9. Establish the next straight-line portion of the p-y curve, p 0.5 pc 6 As 0.411 pc 0.0625 pc y 6 As y 50 ........................ (3-33) y 50 Equation 3-33 should define the portion of the p-y curve from the point where y is equal to 6Asy50 to a point where y is equal to 18Asy50 (see note in Step 10). 10. Establish the final straight-line portion of the p-y curve, p 0.5 pc 6 As 0.411 pc 0.75 pc As ................................... (3-34) or p pc 1.225 As 0.75 As 0.411 ...................................... (3-35) Equation 3-34 should define the portion of the p-y curve from the point where y is equal to 18Asy50 and for all larger values of y, see the following note. Note: The p-y curve shown in Figure 3-17 is drawn, as if there is an intersection between Equation 3-29 and 3-31. However, for small values of k there may be no intersection of Equation 3-29 with any of the other equations defining the p-y curve. Equation 3-29 defines the p-y curve until it intersects with one of the other equations or, if no intersection occurs, Equation 3-29 defines the full p-y curve. 3-3-8-4 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves for Cyclic Loading A second pile, identical in dimensions to the pile used for the static loading, was tested under cyclic loading conditions. The following p-y computation procedure is for cyclic loading conditions and its form is illustrated in Figure 3-18. As may be seen from an examination of the p-y curves that are recommended, the results of load tests performed at the Manor site showed a very large loss of soil resistance. The data from the tests have been studied carefully and the recommended p-y curves for cyclic loading accurately reflect the behavior of the soil present at the site. Nevertheless, the loss of resistance due to cyclic loading for the soils at Manor is much 78 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock more than has been observed elsewhere. Therefore, the use of the recommendations in this section for cyclic loading will yield conservative results for many clays. Long (1984) was unable to show precisely why the loss of resistance occurred during cyclic loading. One observation was that the clay from Manor was found to lose volume by slaking when a specimen was placed in fresh water. Thus, the clay at the site of the load test was quite susceptible to erosion from the hydraulic action of the free water flushing from the annular gap around the pile as the pile was pushed back and forth during cyclic loading. p y 0.45 y p p Ac pc 1 0.45 y p 2.5 Esi kc x A c pc Esc 0.085 pc y50 y p 4.1As y50 Esi kc x 0 y50 50b 0.45yp 0.6yp 1.8yp y Figure 3-18 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Cyclic Loading of Stiff Clay with Free Water 1. Obtain values of undrained shear strength c, effective unit weight , and pile diameter b. 2. Compute the average undrained shear strength ca over the depth x. 3. Compute the soil resistance per unit length of pile, pc, using the smaller of the pct or pcd from Equations 3-26 and 3-27. 4. Choose the appropriate value of Ac from Figure 3-10 on page 74 or compute Ac as a function of x/b using Ac 0.2 0.1tanh1.5x / b ............................................. (3-36) 5. Compute yp using y p 4.1Ac y50 ....................................................... (3-37) 6. Establish the initial linear portion of the p-y curve, using the appropriate value of ks for static loading or kc for cyclic loading from Table 3-3 for k. and compute p using Equation 3-29. 79 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 7. Compute y50 using Equation 3-30. 8. Establish the parabolic portion of the p-y curve, y 0.45 y p p Ac pc 1 0.45 y p 2.5 ........................................... (3-38) Equation 3-38 should define the portion of the p-y curve from the point of the intersection with Equation 3-29 to where y is equal to 0.6yp (see note in step 9). 8. Establish the next straight-line portion of the p-y curve, p 0.936 Ac pc 0.085 pc ( y 0.6 y p ) ................................... (3-39) y 50 Equation 3-39 should define the portion of the p-y curve from the point where y is equal to 0.6yp to the point where y is equal to 1.8yp (see note on Step 9). 9. Establish the final straight-line portion of the p-y curve, p 0.936 Ac pc 0.102 pc y p ........................................... (3-40) y 50 Equation 3-40 defines the p-y curve from the point where y equals 1.8yp and all larger values of y (see following note). Note: Figure 3-18 is drawn, as if there is an intersection between Equation 3-29 and Equation 3-38. There may be no intersection of Equation 3-29 with any of the other equations defining the p-y curve. If there is no intersection, the equation should be employed that gives the smallest value of p for any value of y. 3-3-8-5 Recommended Soil Tests for Stiff Clays in the Presence of Free Water Triaxial compression tests of the unconsolidated-undrained type with confining pressures equal to in-situ total stresses are recommended for determining the shear strength of the soil. The value of 50 should be taken as the strain during the test corresponding to the stress equal to onehalf the maximum total-principal-stress difference. The shear strength, c, should be interpreted as one-half of the maximum total-principal-stress difference. Values obtained from triaxial tests might be somewhat conservative but would represent more realistic strength values than other tests. The unit weight of the soil must be determined. 3-3-8-6 Examples Example p-y curves were computed for stiff clay for a pile with a diameter of 610 mm (24 in.). The soil profile that was used is shown in Figure 3-19. The submerged unit weight of the soil was 7.9 kN/m3 (50 pcf) over the full depth. In the absence of a stress-strain curve, 50 was taken as 0.005 for the full depth of the soil profile. The slope of the initial portion of the p-y curve was established by assuming a value of k of 135 MN/m3 (500 pci). The loading was assumed as cyclic. The p-y curves were computed for 80 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock the following depths below the ground surface: 0.6 m (0.2 ft), 1.5 m (5 ft), 3 m (10 ft), and 12 m (40 ft). The plotted curves are shown in Figure 3-20. 0 2 Depth, meters 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 0 50 100 150 200 Shear Strength, kPa Figure 3-19 Example Shear Strength Profile for p-y Curves for Stiff Clay with No Free Water 250 Depth = 1.00 m Depth = 2.00 m Depth = 3.00 m Depth = 12.00 m Load Intensity p, kN/m 200 150 100 50 0 0.0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 Lateral Deflection y, meters 0.03 0.035 Figure 3-20 Example p-y Curves for Stiff Clay in Presence of Free Water for Cyclic Loading 81 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-3-9 Response of Stiff Clay with No Free Water 3-3-9-1 Background A lateral-load test was performed at a site in Houston, Texas on a drilled shaft (bored pile), with a diameter of 915 mm (36 in.). A 254-mm (10 in)-diameter steel pipe instrumented with strain gages was positioned at the central axis of the pile before concrete was placed. The embedded length of the pile was 12.8 m (42 ft). The average undrained shear strength of the clay in the upper 6 m (20 ft) was approximately 105 kPa (2,200 psf). The experiments and their interpretation were reported in the papers by Welch and Reese (1972) and by Reese and Welch (1975). The same experimental setup was used to develop both the static and the cyclic p-y curves, contrary to the procedures employed for the two other experiments with piles in clays. The load was applied in only one direction rather than in two directions, also in variance with the other experiments. A load was applied and maintained until the strain gages were read with a high-speed data-acquisition system. The same load was then cycled for a number of times and held constant while the strain gages were read at specific numbers of cycles of loading. The load was then increased and the procedure was repeated. The difference in the magnitude of successive loads was relatively large and the assumption was made that cycling at the previous load did not influence the readings for the first cycle at the new higher load. The p-y curves obtained for these load tests were relatively consistent in shape and showed the increase in lateral deflection during cyclic loading. This permitted the expressions of lateral deflection to be formulated in terms of the stress level and the number of cycles of loading. Thus, the engineer can specify a number of cycles of loading (up to a maximum of 5,000 cycles of loading) in doing the computations for a particular design. 3-3-9-2 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves for Stiff Clay without Free Water for Static Loading The following procedure is for short-term static loading and the p-y curve for stiff clay without free water is illustrated in Figure 3-21. 1. Obtain values for undrained shear strength c, effective unit weight , and pile diameter b. Also, obtain the values of 50 from stress-strain curves. If no stress-strain curves are available, use a value of 50 of 0.010 or 0.005 as given in Table 3-2, the larger value being more conservative. 2. Compute the ultimate soil resistance, pu, per unit length of pile using the smaller of the values given by Equation 3-20 or Equation 3-21. Note that in the use of Equation 3-20, the shear strength is taken as the average between the ground surface and the depth being considered, J is taken as 0.5, and the average effective unit weight of the soil should reflect the position of the water table. 82 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p p pu y p 0.5 pu y50 1 4 y 16y50 Figure 3-21 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curve for Static Loading in Stiff Clay without Free Water avg avg J 0.5 pu 3 x x cb 3 x x cb .............................(3-20) b b cavg cavg pu 9 c b ...........................................................(3-21) 3. Compute the deflection, y50, at one-half the ultimate soil resistance using Equation 3-23. y50 2.5 50b ........................................................ (3-23) 4. Compute points describing the p-y curve from the relationships below. p y p u 2 y50 0.25 ..................................................... (3-41) 4 p y y50 2 ....................................................(3-42) pu 5. Beyond y = 16y50, p is equal to pu for all values of y. 3-3-9-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves for Stiff Clay without Free Water for Cyclic Loading The following procedure is for cyclic loading and the p-y curve for stiff clay without free water is illustrated in Figure 3-22. 83 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock pu N1 N3 N2 yc = ys + y50 C log N3 yc = ys + y50 C log N2 yc = ys + y50 C log N1 16y50+9.6(y50)logN1 y 16y50+9.6(y50)logN3 16y50+9.6(y50)logN2 Figure 3-22 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Cyclic Loading in Stiff Clay with No Free Water 1. Determine the p-y curve for short-term static loading by the procedure previously given. 2. Determine the number of times the lateral load will be applied to the pile. 3. Obtain the value of C for several values of p/pu, where C is the parameter describing the effect of repeated loading on deformation. The value of C is found from a relationship developed by laboratory tests, (Welch and Reese, 1972), or in the absence of tests, from 4 p ....................................................... (3-43) C 9.6 pu 4. At the value of p corresponding to the values of p/pu selected in Step 3, compute new values of y for cyclic loading from yc y s y50C log N ................................................. (3-44) Cyclic deflection is computed from the ratio p/pu using 4 p 4 p yc y50 2 y50 9.6 log N ................................(3-45) pu pu where: yc = deflection under N-cycles of loading, ys = deflection under short-term static loading, 84 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock y50 = deflection under short-term static loading at one-half the ultimate resistance computed using Equation 3-23, and N = number of cycles of loading. The net effect of cyclic loading is to expand the p-y curve in the y-direction. The ratio of expansion is defined as the ratio of cyclic deflection over static deflection for an equal ratio of p/pu. The expansion ratio as a function of number of cycles of loading is shown in the figure below. As an example, the width of a p-y curve for 2,000 cycles of loading is approximately three times “wider” than the static p-y curve. 3.5 Ratio of Expansion 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 1 10 100 1000 10000 Cycles of Loading Figure 3-23 Ratio of Expansion versus Number of Cycles of Loading for Stiff Clay without Free Water 3-3-9-4 Recommended Soil Tests for Stiff Clays Triaxial compression tests of the unconsolidated-undrained type with confining stresses equal to the overburden pressures at the elevations from which the samples were taken are recommended to determine the shear strength. The value of 50 should be taken as the strain during the test corresponding to the stress equal to one-half the maximum total-principal-stress difference. The undrained shear strength, c, should be defined as one-half the maximum totalprincipal-stress difference. The unit weight of the soil must also be determined. 3-3-9-5 Examples An example set of p-y curves was computed for stiff clay above the water table for a pile with a diameter of 610 millimeters (24 in.). The soil profile that was used is shown in Figure 385 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 19. A unit weight for soil of 19.0 kN/m3 (125 pcf) was assumed for the entire soil profile. In the absence of a stress-strain curve, 50 was taken as 0.005. Equation 3-43 was used to compute values for the parameter C and it was assumed that there were to be 100 cycles of loading. The p-y curves were computed for the following depths below the ground line: 0.6 m (2 ft), 1.5 m (5 ft), 3 m (10 ft), and 12 meters (40 feet). The plotted curves are shown in Figure 324. 400 Load Intensity p, kN/m 300 200 Depth = 0.60 m Depth = 1.50 m Depth = 3.00 m Depth = 12.00 m 100 0 0.0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.2 Lateral Deflection y, meters 0.25 0.3 Figure 3-24 Example p-y Curves for Stiff Clay with No Free Water, Cyclic Loading 3-3-10 Modified p-y Formulation for Stiff Clay with No Free Water The p-y formulation for stiff clay with no free water was described in Section 3-3-9. The p-y curve for stiff clay with no free water is based on Equation 3-41, which does not contain an initial stiffness parameter k. Although the formulation for stiff clay without free water has been used successfully for many years, there have been cases reported from the Southeastern United States where load tests on full-size piles have found that the initial slope of the load-deformation response modeled using the original formulation is too stiff. The ultimate load-transfer resistance pu used in the p-y formulation is consistent with the theory of plasticity and has also correlated well with the results of load tests. However, the soil resistance at small deflections is influenced by factors such as soil moisture content, clay mineralogy, clay structure, possible desiccation, and pile diameter. Brown (2002) has recommended using a field-calibrated k value to modify the initial portion of the p-y curves if one has the results of lateral load test for calibration of the initial stiffness k. Judicious use of this modified p-y formulation enables one to obtain improved predictions with experimental readings that may be used later for design computations. 86 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The user may select an initial stiffness k based on Table 3-3 on page 89 or from a sitespecific lateral load test. LPile will use the lower of the p values computed using Equation 3-29 or Equation 3-41 for pile response as a function of lateral pile displacement. One drawback of the modified p-y formulation for stiff clay with no free water is that pvalues for a p-y curve computed at the ground surface will always be zero. This is not the case for the unmodified formulation. 3-3-11 Other Recommendations for p-y Curves in Clays As noted earlier in this chapter, the selection of the set of p-y curves for a particular field application is a critical feature of the method of analysis. The presentation of three particular methods for clays does not mean the other recommendations are not worthy of consideration. Some of these methods are mentioned here for consideration and their existence is an indication of the level of activity with regard to the response of soil to lateral deflection. Sullivan, et al. (1980) studied data from tests of piles in clay when water was above the ground surface and proposed a procedure that unified the results from those tests. While the proposed method was able to predict the behavior of the experimental piles with excellent accuracy, two parameters were included in the method that could not be found by any rational procedures. Further work could develop means of determining those two parameters. Stevens and Audibert (1979) reexamined the available experimental data and suggested specific procedures for formulating p-y curves. Bhushan, et al. (1979) described field tests on drilled shafts under lateral load and recommended procedures for formulating p-y curves for stiff clays. Briaud, et al. (1982) suggested a procedure for use of the pressuremeter in developing p-y curves. A number of other authors have also presented proposals for the use of results of pressuremeter tests for obtaining p-y curves. O’Neill and Gazioglu (1984) reviewed all of the data that were available on p-y curves for clay and presented a summary report to the American Petroleum Institute. The research conducted by O’Neill and his co-workers (O’Neill and Dunnavant, 1984; Dunnavant and O’Neill, 1985) at the test site on the campus of the University of Houston developed a large volume of data on p-y curves. This work will most likely result in specific recommendations in due course. 3-4 p-y Curves for Cohesionless Soils 3-4-1 Description of p-y Curves in Sands 3-4-1-1 Initial Portion of Curves The initial stiffness of stress-strain curves for sand is a function of the confining pressure and magnitude of shearing strain; therefore, the use of mechanics for obtaining the initial Es for pile design sands is complicated due to the complex strain fields around a pile. The p-y curve at the ground surface will be characterized by zero values of p for all values of y, because the vertical effective stress at the surface is zero. The initial slope of the p-y curves and the ultimate resistance on the p-y curve will increase approximately linearly with depth. A presentation of the recommendations of Terzaghi (1955) is of interest here, but it is now recognized that his coefficients probably are meant to reflect the slope of secants to p-y 87 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock curves rather than the initial moduli. As noted earlier, Terzaghi recommended the use of his coefficients up to the point where the computed soil resistance was equal to about one-half of the ultimate bearing stress. In terms of p-y curves, Terzaghi recommended a series of straight lines with slopes that increase linearly with depth, as indicated in Equation 3-46. Es k x .......................................................... (3-46) where k is a constant giving the variation of soil modulus with depth, and x is the depth below ground surface. Terzaghi’s recommended values for k values in both US customary units and SI units are presented in Table 3-5. The k values recommended by Terzaghi in Table 3-5 are now known to be too conservative. Users of LPile are advised to use the values recommended by Reese and Matlock presented later in this manual because those values are based on load tests of fully instrumented piles and are supported by high quality soil investigations. Terzaghi’s recommended values were based on a literature review conducted in the early 1950’s, not a direct evaluation of pile load testing results, and should be recognized as being preliminary recommendations. Terzaghi later acknowledged around 1958 that he had some doubts about the source data and he ceased recommending use of the values shown in Table 3-5. 3-4-1-2 Analytical Solutions for Ultimate Resistance Two models are used for computing the ultimate resistance for piles in sand. These models follow a procedure similar to that used for clay. The first of the models for the soil resistance near the ground surface is shown in Figure 3-25. The total lateral force Fpt (Figure 325(c)) may be computed by subtracting the active force Fa, computed by use of Rankine theory, from the passive force Fp, computed for the model by assuming that the Mohr-Coulomb failure condition is satisfied on vertical wedge side planes defined by ADE and BCF, and on the sloping wedge surface defined by AEFB in Figure 3-25(a). The directions of the resultant forces are shown in Figure 3-25(b). Solutions other than the ones shown here have been developed by assuming a friction force on the pile-soil interface surface defined by DEFC (assumed to be zero in the analysis shown here) and by assuming the water table to be within the wedge (the unit weight is assumed to be constant in the analysis shown here). Table 3-5 k Values Recommended by Terzaghi for Laterally Loaded Piles in Sand Relative Density Loose Medium Dense k, MN/m3 (pci) Dry or Moist Sand Submerged Sand 0.95 - 2.8 0.53 - 1.7 (3.5 - 10.4) (2.1 - 6.4) 3.5 - 10.9 2.2 - 7.3 (13.0 - 40.0) (8.0 - 27.0) 13.8 - 27.7 8.3 - 17.9 (51.0 - 102.0) (32.0 - 64.0) 88 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock B Fs A y Ff F Fs C Fn x D W H Fp Fn Ft Fp (b) Fp (a) E b Pile of Diameter b Fs Fn F Ff W Fpt Fa (c) Figure 3-25 Geometry Assumed for Passive Wedge Failure for Pile in Sand The total lateral force Fpt may be computed by following a procedure similar to that used to solve the equation in the clay model (Figure 3-6). The resulting equation is K H tan tan tan H Fpt H 2 0 tan tan 3 tan( ) cos tan( ) 2 3 ............... (3-47) K Ab 2 K 0 H tan tan sin tan H 3 2 where: = the angle of the wedge in the horizontal direction = is the angle of the wedge with the ground surface, b = is the pile diameter, H = the height of the wedge, K0 = coefficient of earth pressure at rest, and KA = coefficient of active earth pressure. The ultimate soil resistance near the ground surface per unit length of the pile is obtained by differentiating Equation 3-47 with respect to depth. 89 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock K H tan sin tan b H tan tan ( pu ) sa H 0 ............... (3-48) tan( ) cos s tan( ) H K0 H tan tan sin tan K Ab Bowman (1958) performed some laboratory experiments with careful measurements and suggested values of from /3 to /2 for loose sand and up to for dense sand. The value of is approximated by the following equation. 45 ......................................................... (3-49) 2 The model for computing the ultimate soil resistance at some distance below the ground surface is shown in Figure 3-26(a). The stress 1 at the back of the pile must be equal or larger than the minimum active earth pressure; if not, the soil could fail by slumping. The assumption is based on two-dimensional behavior; thus, it is subject to some uncertainty. If the states of stress shown in Figure 3-26(b) are assumed, the ultimate soil resistance for horizontal movement of the soil is pu sb K AbH tan8 1 K0bH tan tan4 ............................ (3-50) The equations for (pu)sa and (pu)sb are approximate because of the elementary nature of the models that were used in the computations. However, the equations serve a useful purpose in indicating the general form, if not the magnitude, of the ultimate soil resistance. 3-4-1-3 Influence of Diameter on p-y Curves No studies have been reported on the influence of pile diameter on p-y curves in sand. The reported case studies of piles in sand, some of which are of large diameter, do not reveal any particular influence of the pile diameter. However, virtually all of the reported lateral-load tests, except the ones described later, have used only static loading. 90 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 5 4 2 4 4 3 3 2 3 1 1 5 6 5 6 5 1 Pile Movement 2 (a) tan (b) Figure 3-26 Assumed Mode of Soil Failure by Lateral Flow Around Pile in Sand, (a) Section Though Pile, (b) Mohr-Coulomb Diagram 3-4-1-4 Influence of Cyclic Loading As noted above, there are very few reports of testing of piles subjected to cyclic lateral loading. In these reports, two types of behavior have been observed and noted. There is clear evidence that the repeated loading on a pile in predominantly one direction will result in a permanent deflection of the pile in the direction of loading. It has been observed during load testing that when a relatively large cyclic load is applied in one direction, the upper section of the pile will deflect enough to allow grains of cohesionless soil to fall into the open 91 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock gap at the back of the pile. Thus in such a case, the pile cannot return to its initial position after cyclic loading ceases causing the development of the permanent deflection. Observations of the shearing behavior of sand near the ground surface during cyclic loading support the idea that the void ratio of sand is approaching a critical value. This means that dense sand will loosen and loose sand will densify under cyclic loading. A careful study of the two phenomena mentioned above should provide information of use to engineers. Full-scale experiments with detailed studies of the nature of the sand around the top of a pile, both before and after loading, would be a welcome contribution. 3-4-1-5 Early Recommendations The values of subgrade moduli recommended by Terzaghi (1955) provided some basis for computation of lateral pile response, but Terzaghi’s values could not be implemented into practice until the digital computer and the required programs became widely available. There was a period of a few years in the 1950’s when engineers were solving the difference equations using mechanical calculators. The piles supporting some early offshore platforms constructed during this era were designed using this method. Parker and Reese (1971) performed some small-scale experiments, examined unpublished data, and recommended procedures for predicting p-y curves for sand. The method of Parker and Reese was little used in practice because the method of Cox, et al. (1974), described later, was based on a comprehensive load testing program on full-sized piles and became available shortly afterward. 3-4-1-6 Field Experiments An extensive series of field tests were performed at a site on Mustang Island, near Corpus Christi, Texas (Cox, et al., 1974). Two steel-pipe piles, 610 mm (24 in.) in diameter, were driven into sand in a manner to simulate the driving of an open-ended pipe and were subjected to lateral loading. The embedded length of the piles was 21 meters (69 feet). One of the piles was subjected to short-term loading and the other to cyclic loading. The soil at the test site was classified as SP using the Unified Soil Classification System,. The sand was poorly graded, fine sand with an angle of internal friction of 39 degrees. The effective unit weight was 10.4 kN/m3 (66 pcf). The water surface was maintained at 150 mm (6 in.) above the ground surface throughout the test program. 3-4-1-7 Response of Sand Above and Below the Water Table The procedure for developing p-y curves for piles in sand is shown in detail in the next section. The piles that were used in the experiments, described briefly below, were the ones used at Manor, except that the piles at Manor had an extra wrap of steel plate. 3-4-2 Reese, et al. (1974) Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Sand The Reese, et al. (1974) following procedure is for both short-term static loading and for cyclic loading for a flat ground surface and a vertical pile. The shape of the p-y curves computed using this procedure is illustrated in Figure 3-27. 92 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p u pu m m pm yu ym k pk yk kx y 3b/80 b/60 Figure 3-27 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for Static and Cyclic Loading in Sand 1. Obtain values for the depth of the p-y curve x, angle of internal friction , effective unit weight of soil , and pile diameter b (Note: use effective unit weight for sand below the water table and total unit weight for sand above the water table). 2. Compute the following parameters: 2 , 45 , K0 0.4 , and K A tan 2 45 ..................... (3-51) 2 2 3. Compute the ultimate soil resistance per unit length of pile, ps, using the smaller of pst or psd ps = min[pst, psd] .................................................... (3-52) where: K x tan sin tan pst x 0 (b x tan tan ) .................... (3-53) tan( ) cos tan( ) K 0 x tan (tan sin tan ) K Ab psd K A b x(tan8 1) K0 b x tan tan4 ............................. (3-54) 4. Compute the y value defining point u using 93 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock yu 3b ........................................................... (3-55) 80 Compute pu defining point u for static loading conditions using pu As ps ......................................................... (3-56) or for cyclic loading conditions using pu Ac ps .......................................................... (3-57) Obtain the appropriate value of As or Ac from Figure 3-28 as a function of the nondimensional depth and type of loading (either static or cyclic). Compute ps using the appropriate equation, either Equation 3-53 or Equation 3-54. As or Ac 2 1 0 3 0 1 2 x b Ac As 3 4 5 x 5.0, A 0.88 b 6 Figure 3-28 Values of Coefficients Ac and As for Cohesionless Soils 5. Compute the y-value at point m using ym b .......................................................... (3-58) 60 Compute pm at point m for static loading conditions using 94 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock pm Bs ps .......................................................... (3-59) or for cyclic loading conditions using pm Bc ps .......................................................... (3-60) Obtain the appropriate value of Bs or Bc from Figure 3-29 as a function of the nondimensional depth and the type of loading (either the static or cyclic). Use the appropriate equation for ps. The two straight-line portions of the p-y curve, beyond the point where y is equal to b/60, can now be determined. Bs or Bc 2 1 0 3 0 1 Bs (static) Bc (cyclic) 2 x b 3 4 5 x 5.0, Bc 0.55, Bs 0.50 b 6 Figure 3-29 Values of Coefficients Bc and Bs for Cohesionless Soils 6. Establish the initial straight-line portion of the p-y curve, p k x y ......................................................... (3-61) Use the appropriate value of k from Table 3-6 or 3-7. If the input value of k is left equal to zero, LPile will compute a default value using the curves shown in Figure 3-34 on page 114. Whether the sand is above or below the water table will be determined from the input value of effective unit weight. If the effective unit weight is less than 77.76 pcf (12.225 kN/m3) the sand is considered to be below the water table. If the input value of is greater than 45 degrees, a k value corresponding to 45 degrees is used by LPile. 95 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Table 3-6 Representative Values of k for Fine Sand Below the Water Table for Static and Cyclic Loading Relative Density Loose Medium Dense 5.4 16.3 34 (20.0) (60.0) (125.0) Recommended k MN/m3 (pci) Table 3-7 Representative Values of k for Fine Sand Above Water Table for Static and Cyclic Loading Recommended k Loose 6.8 (25.0) MN/m3 (pci) Relative Density Medium Dense 24.4 61.0 (90.0) (225.0) If the sand profile is coarse or well-graded sand, the user may consider using a higher value of k that those suggested in the tables above. While experimental data for k in wellgraded sands is poorly documented, use of values 10 to 50 percent higher may be appropriate in dense and very dense well-graded sands that do not contain any compressible minerals such as mica. 7. Fit the parabola between point k and point m as follows: a. Compute the slope of the p-y curve between point m and point u using m pu p m ........................................................ (3-62) yu y m b. Compute the power of the parabolic section using n pm ........................................................... (3-63) m ym C pm ........................................................... (3-64) y1m/ n c. Compute the coefficient C using 8. Compute the y value defining point k using n C n 1 y k ........................................................ (3-65) kx Compute the p value defining point k using 96 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock pk k x yk 9. Compute p-values along the parabolic section of the p-y curve between points k and m using p C y1/ n .......................................................... (3-66) Note: The curve in Figure 3-27 is drawn as if there is an intersection between the initial straight-line portion of the p-y curve and the parabolic portion of the curve at point k. However, in some instances there may be no intersection with the parabola. Equation 361 defines the p-y curve until there is an intersection with another portion of the p-y curve or if no intersection occurs, Equation 3-61 defines the complete p-y curve. If yk is in between points ym and yu, the curve is tri-linear and if yk is greater than yu, the curve is bilinear as shown in Figure 3-30. p Lower k x kx Higher k x kx y Figure 3-30 Illustration of Effect of k on p-y Curve in Sand 3-4-2-1 Recommended Soil Tests Fully drained triaxial compression tests are recommended for obtaining the angle of internal friction of the sand. Confining pressures should be used which are close to or equal to the effective overburden stresses at the depths being considered in the analysis. Tests must be performed to determine the unit weight of the sand. However, it may be impossible to obtain undisturbed samples and frequently the angle of internal friction is estimated from results of some type of in-situ test. The procedure above can be used for sand above the water table if appropriate adjustments are made in the unit weight and angle of internal friction of the sand. Some smallscale experiments were performed by Parker and Reese (1971) and recommendations for the p-y curves for dry sand were developed from those experiments. The results from the Parker and 97 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Reese experiments should be useful in checking solutions from results of experiments with fullscale piles. 3-4-2-2 Example Curves An example set of p-y curves was computed for sand below the water table for a pile with a diameter of 610 mm (24 in.). The sand properties are assumed to be an angle of internal friction of 35 degrees and a submerged unit weight of 9.81 kN/m3 (62.4 pcf). The loading was assumed as static. The p-y curves were computed for the following depths below the mudline: 1.5 m (5 ft), 3 m (10 ft), 6 m (20 ft), and 12 meters (40 feet). The plotted curves are shown in Figure 3-31. 4,000 Load Intensity, p, kN/m 3,500 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 Lateral Deflection, y, meters 1.5 m 3.0 m 6.0 m 12 m Figure 3-31 Example p-y Curves for Sand Below the Water Table, Static Loading 3-4-3 API RP 2A Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Sand 3-4-3-1 Background of API Method for Sand This procedure is recommended by the American Petroleum Institute in its manual for recommended practice for designing fixed offshore platforms (API RP 2A). Thus, the method has official recognition. The API procedure for p-y curves in sand was based on a number of field experiments. There is no difference for ultimate resistance (pu) between the Reese et al. criteria and the API procedure. The API method uses a hyperbolic tangent function for computation of the curve. The main difference between those two criteria will be the initial modulus of subgrade reaction and the shapes of the curves. 98 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-4-3-2 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves Using the API Sand Method The following procedure is for both short-term static loading and for cyclic loading as described in API RP2A (2010). 1. Obtain values for the angle of internal friction , the effective unit weight of soil, , and the pile diameter b. 2. Compute the ultimate soil resistance at a selected depth x. The ultimate lateral bearing capacity (ultimate lateral resistance pu) for sand has been found to vary from a value at shallow depths determined by Equation 3-67 to a value at deep depths determined by Equation 3-68. At a given depth, the equation giving the smallest value of pu should be used as the ultimate bearing capacity. The value of pu is the lesser of pu at shallow depths, pus, or pu at great depth, pud , where: pus (C1 x C2b) x ................................................. (3-67) pud C3b x ........................................................ (3-68) where: pu = ultimate resistance (force/unit length), lb./in. (kN/m), = effective unit weight, pci (kN/m3), x = depth, in. (m), = angle of internal friction of sand, degrees, C1, C2, C3 = coefficients determined from Figure 3-32 as a function of , or from: 1 C1 tan K P tan K 0 tan sin 1 tan cos C2 K P K A C3 K P2 K P K 0 tan K A where K p tan 2 45 2 and K 0 0.4 99 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 5 100 90 4 80 3 60 C2 50 2 Values of C3 Values of C1 and C2 70 40 C1 30 C3 1 20 10 0 0 20 25 30 35 40 Angle of Friction, degrees Figure 3-32 Coefficients C1, C2, and C3 versus Angle of Internal Friction b = average pile diameter from surface to depth, in. (m). 3. Compute the load-deflection curve based on the ultimate soil resistance pu which is the minimum value of pu calculated in Step 2. The lateral soil resistance-deflection (p-y) relationships for sand are nonlinear and, in the absence of more definitive information, may be approximated at any specific depth x by the following expression: kx p A pu tanh A pu y ................................................ (3-69) where A = factor to account for cyclic or static loading. Evaluated by: A = 0.9 for cyclic loading. 100 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock x A 3.0 0.8 0.9 for static loading, b pu = smaller of values computed from Equation 3-67 or 3-68, lb./in. (kN/m), k = initial modulus of subgrade reaction, pci (kN/m3). Determine k from Figure 3-33 as a function of angle of internal friction, , y = lateral deflection, in. (m), and x = depth, inches (m). f, Friction Angle, degrees 28 29 Very Loose 36 30 Medium Loose 41 Dense 45 Very Dense 300 80 70 Fine Sand Above the Water Table 250 60 200 150 40 k, MN/m3 k, lb/in3 50 30 100 Fine Sand Below the Water Table 20 50 10 0 0 20 40 60 80 0 100 Relative Density, % Figure 3-33 Value of k for API Sand Procedure2 2 It should be noted that Figure 3-32 has been corrected and differs from a similar figure presented in API RP-2A. The positions of the labels for relative density on the bottom axis have moved to their correct positions, the label for friction angle at the division line between dense and very dense sand has be corrected to the correct value of 41 degrees, and the scale in SI units has been added. 101 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock LPile will assign a default value for k if the user enters a value of zero. The value of k is determined from the angle of friction and it is assumed that the sand is fine. The equations used by LPile to determine k as a function of friction angle for fine sand are shown in Figure 3-34. Whether the sand is above or below the water table will be determined from the input value of effective unit weight. If the effective unit weight is less than 77.76 pcf (12.225 kN/m 3) the sand is considered to be below the water table. If the input value of is greater than 45 degrees, a k value corresponding to 45 degrees is used by LPile. The two correlation lines intersect at a friction angle value of 27.6423 degrees and a k value of 10.2068 pci. If the input value of is less than 27.6423 degrees, the value of k linearly varies from a value of zero at zero degrees to a value of 10.2068 pci at 27.6423 degrees If the sand profile is coarse or well-graded sand, the user may consider using a higher value of k that those suggested in the Figure 3-34. While experimental data for k in well-graded sands is sparse, use of k values 10 to 50 percent higher may be appropriate in dense and very dense well-graded sands that do not contain any compressible minerals such as mica. 400 350 Fine Sand Above the Water Table k = 0.4168 2 - 8.1254 - 83.664 300 k, psi 250 200 150 100 50 Fine Sand Below the Water Table k = 0.0166 3 - 1.5526 2 + 58.43 -769.18 0 25 30 35 40 , Angle of Friction, Degrees 45 Figure 3-34 Value of k versus Friction Angle for Fine Sand Used in LPile 3-4-3-3 Example Curves An example set of p-y curves was computed for sand above the water table, using the API criteria. The soil properties are unit weight = 0.07 pci, and internal-friction angle = 35 degrees. The sand layer exists from the ground surface to a depth of 40 feet. The pile is of 102 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock reinforced concrete; the geometry and properties are: pile length = 25 feet, diameter = 36 in., moment in inertia = 82,450 in.4 and the modulus of elasticity = 3.6 106 psi. The loading is assumed as static. The p-y curves are computed for the following depths: 20 in., 40 in., and 100 inches. A hand calculation for p-y curves at a depth of 20 in. was made to check the computer solution, as shown in the following. 1. List the soil and pile parameters = 0.070 pci = 35 degrees b = 36 inches 2. Obtain coefficients C1, C2, C3 from Figure 3-32. C1 = 2.97 C2 = 3.42 C3 = 53.8 3. Compute the ultimate soil resistance pu. pus = (C1 x + C2 b) x = [(2.97)(20 in.) + (3.42)(36 in.)](0.07 pci)(20 in) = 255 lb./in. pud = C3 b x = (53.8)(36 in. )(0.07 pci) (20 in.) = 2,711 lb./in. pu = pus = 255 lb./in. (smaller value) 4. Compute coefficient A A = 3.0 – (0.8) (x)/(b) = 3.0 – (0.8)(20 in.)/(36 in.) = 2.56 5. Compute p for different y values. If y = 0.1 inch, k (above water table) = 140 pci (from Figure 3-33) kx p A pu tanh A pu y (140 lb./in. 3 )(20 in.) p (2.55)(255 lb./in. ) tanh (0.1 in.) (2.55)(255 lb./in. ) p 264 lb./in. (computer output = 264.012 lb./in.) If y = 1.35 in. kx p A pu tanh A pu y (140)(20 in.) p (2.55)(255 lb./in.) tanh (1.35 in.) 3 (2.55)(255 lb/in. ) p 653 lb./in. (computer output = 652.93 lb./in.) 103 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The check by hand computations yielded exact values for the two values of deflection that were considered. The computed curves are presented in Figure 3-35. 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 0.0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1.0 1.25 1.5 1.75 2.0 Lateral Deflection y, in. Depth = 20.00 in. Depth = 40.00 in. Depth = 100.00 in. Figure 3-35 Example p-y Curves for API Sand Criteria 3-4-4 Other Recommendations for p-y Curves in Sand A survey of the available information of p-y curves for sand was made by O’Neill and Murchison (1983), and some changes were suggested in the procedure given above. Their suggestions were submitted to the American Petroleum Institute and modifications were adopted by the API review committee. Bhushan, et al. (1981) reported on lateral load tests of drilled piers in sand. A procedure for predicting p-y curves was suggested. A number of authors have discussed the use of the pressuremeter in obtaining p-y curves. The method that is proposed is described in some detail by Baguelin, et al. (1978) . 3-5 p-y Curves for Liquefied Soils 3-5-1 Response of Piles in Liquefied Sand The lateral resistance of deep foundations in liquefied sand is often critical to the design. Although reasonable methods have been developed to define p-y curves for non-liquefied and, 104 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock considerable uncertainty remains regarding how much lateral load-transfer resistance can be provided by liquefied sand. In some cases, liquefied sand is assumed to have no lateral resistance. This assumption can be implemented in LPile either by using appropriate p-multiplier values or by entering a very low friction angle for sand. When sand is liquefied under undrained conditions, some suggest that it behaves in a manner similar to the behavior of soft clay. Wang and Reese (1998) have studied the behavior of piles in liquefied soil by modeling the liquefied sand as soft clay. The p-y curves were generated using the model for soft clay by equating the cohesive strength equal to the residual strength of liquefied sand. The strain factor 50 was set equal to 0.05 in their study. Laboratory procedures cannot measure the residual shear strength of liquefied sand with reasonable accuracy due to the unstable nature of the soil. Some case histories must be evaluated to gather information on the behavior of liquefied deposit. Recognizing the need to use case studies, Seed and Harder (1990) examined cases reported where major lateral spreading has occurred due to liquefaction and where some conclusions can be drawn concerning the strength and deformation of liquefied soil. Unfortunately, cases are rare where data are available on strength and deformation of liquefied soils. However, a limited number of such cases do exist, for which the residual strengths of liquefied sand and silty sand can be determined with a reasonable accuracy. Seed and Harder found that a residual strength of about 10 percent of the effective overburden stress can be used for liquefied sand. Although simplified methods based on engineering judgment have been used for design, full-scale field tests are needed to develop a full range of p-y curves for liquefied sand. Rollins et al. (2005b) have performed full-scale load tests on a pile group in liquefied sand with an initial relative density between 45 and 55 percent. The p-y curves that were developed from these studies have a concave upward shape, as illustrated in Figure 3-36. This characteristic shape appears to result primarily from dilative behavior during shearing, although gapping effects may also contribute to the observed load-transfer response. Rollins and his co-workers also found that p-y curves for liquefied sand stiffen with depth (or initial confining stress). With increasing depth, small displacement is required to develop significant resistance and the rate at which resistance develops as a function of lateral pile displacement also increases. 105 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p y 150 mm Figure 3-36 Example p-y Curve in Liquefied Sand Following liquefaction, p-y curves in sand become progressively stiffer with the passage of time as excess pore water pressures dissipate and return to hydrostatic levels. The shape of a p-y curve appears to transition from concave up to concave down as pore water pressures decrease. A model based on load tests has been developed by Rollins et al. (2003) to describe the observed load-displacement response of piles in liquefied sand as a function depth. 3-5-2 Method of Rollins et al. (2005a) The expression developed by Rollins et al. (2005a) for p-y curves in liquefied sands at different depths is shown below is based on their fully-instrumented load tests. Coefficients for these equations were fit to the test data using a trial and error process in which the errors between the target p-y curves and those predicted by the equations were minimized. The resulting equations were then compared, and the equation that produced the most consistent fit was selected. p0.3 m A By ≤ 15 kN/m .............................................(3-70) C A 3 107 z 1 6.05 ...................................................(3-71) B 2.80( z 1) 0.11 .....................................................(3-72) C 2.85z 1 0.41 .....................................................(3-73) Where: p0.3 m = soil resistance in kN/meter for a reference pile with a diameter of 0.3 meters, y = lateral deflection of the pile in millimeters, z = depth in meters (see note in last paragraph of this section, and 106 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock A, B, C are functions of the depth in meters. Note that the engineering units of pile diameter is in meters, pile displacement is in millimeters, depth is in meters, and computed values lateral load transfer are in kilonewtons per meter. The end of the upward curve is at a displacement of 150 mm only if p0.3 m is less than 15 kN/m at a y value of 150 mm. If p0.3 m reaches 15 kN/m at a value of y smaller than 150 mm, the upward curve is ended at that value of y. If the pile diameter differs from 0.3 m, the value of p is scaled by a diameter modification factor. The diameter modification factor is discussed below. Rollins et al. (2005a) studied the diameter effects for different sizes of piles and recommended using a modification factor for adjusting Equation 3-70. The modification factor for pile diameters between 0.3 and 2.6 meters is Pd 3.81 ln b 5.6 ...................................................(3-74) where b is the diameter of the pile or drilled shaft in meters. The p value for the reference diameter of 0.3 meters can be multiplied by Pd to obtain values for p values for piles of varying diameters using the equation below. p( y) Pd p0.3 m .......................................................(3-75) Note that the diameter modification factor has been experimentally validated for pile diameters ranging from 0.3 to 2.6 meters. For pile diameters smaller than 0.3 meters, the procedure is to compute p0.3 m for a diameter of 0.3 meters then multiply by the ratio of the pile diameter over 0.3 meters. Thus, for pile diameters less than 0.3 meters, the diameter modification factor is computed from b b Pd 3.81ln 0.3 m 5.6 1.0129 .........................(3-76) 0.3 m 0.3 m Where the pile diameter b is in meters. For pile diameters greater than 2.6 meters, the value of Pd is constant and equal to 9.24. Application of Equation 3-70 should generally be limited to conditions comparable to those from which it was derived. These conditions are: Relative density between 45 and 55 percent, Lateral soil resistance less than 15 kN/meter for the reference diameter of 0.3 meters, Lateral pile deflection less than 150 mm (0.15 m), Depths of 6 meters or less, and Position of the water table is near to or at the ground surface. 107 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock In some cases, the liquefying layer may not be at the surface. In such cases, the depth variable (z) may be modified to a depth equal to the initial vertical effective stress divided by an effective unit weight of 10 kN/m3, which is generally representative of the unit weight of the sand at the site. 3-5-3 Simplified Hybrid p-y Model Franke and Rollins (2013) developed the simplified hybrid p-y spring model that combines the features of the Rollins et al. (2005a) model and the residual strength model suggested by Wang and Reese (1998) . In this model, two p-y curves are computed. One curve is the curve computed using the Rollins et al. (2005a) method. The second curve is based on the Matlock method for p-y curves in soft clay under static loading conditions in which the cohesive strength of the soil is based on the Seed and Harder (1990) curves of residual strength of liquefied soils. Franke and Rollins (2013) developed a model that combines the curves for dilative liquefied sand developed by Rollins, et al. (2005a) with the Reese and Wang (1998) concept of a residual strength curve computed using the residual strength curve developed by Seed and Harder (1990). This model is referred to as the hybrid model for liquefied sands. The concept used to formulate the hybrid model is to compute the p-y curves for the dilative behavior based on the equations developed by Rollins, et al. (2005a) and for the residual strength behavior based on the soft clay equations for static loading conditions developed by Matlock (1970). The hybrid model uses the lowest p-value computed using either model for a given y-value. All input values need to be converted to SI units before computation of the hybrid p-y curve. The sole exception to this is that the correlation from SPT blowcount to residual strength outputs residual strength in units of psf. This model combines the Matlock soft clay model for static conditions using residual strengths correlated to SPT blowcount and the Ashford and Rollins dilative liquefied sand model. The model uses the lowest p-value computed using either model for a given y-value. The equations for the dilative model are the same as those presented by Rollins, et a. (2005a) before. 3-5-3-1 Equations for Simplified Hybrid p-y Curve Define the engineering units to be depth z in meters, pile diameter b in meters, and y in millimeters. The equations are: 108 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p ABy C A 3 10 7 z 1 6.05 B 2.80 z 1 0.11 C 2.85 z 1 0.41 p 0.3m min A(150 B) C , 15 kN/m Pd 3.81ln b 5.6 for diameters between 0.3 m and 2.6 m p d b / 0.3m for diameters less than 0.3 m pu Pd p 0.3m p y Pd ABy pu for y values up to 150 mm C Where: A, B, and C are dimensionless functions of the depth of the curve z in meters, p0.3m is the maximum dilative resistance for a 0.3 m diameter pile, Pd is a dimensionless factor to adjust for pile diameter, pu is the peak lateral load intensity, and 50 is the 50 value required to compute the Matlock soft clay curve. The parameter p0.3m is the lesser of the computed dilative resistance at a displacement of 150 mm or 15 kN/m. The equations for the p-y curves using residual strengths are those developed by Matlock (1970) for soft clays under static loading conditions. The equations and p-y curve for soft clay are presented in Figure 3-12(a). The peak load-transfer capacity is computed using avg J pu min 3 z z Surb, 9cb Sur b given that J = 0.5 and Sur substituted for c. The pile diameter is accounted for by the factor y50. This factor is computed using y50 2.5 50b The curved portion of the p-y curve is computed using p p u 2 y y50 1 3 for y ≤ 8y50 The lateral load-transfer is constant and equal to pu for lateral pile deflections greater than 8y50. 109 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The engineering units used in the three equations above are consistent units of force and length. The units may be lbs and ft, lbs and inches, or kN and meters. See the hybrid model equations for the correlation of SPT blowcounts to 50. 3-5-3-2 Correlation for 33% residual strength as function of SPT (N1)60-cs -value: 2,000 Earthquake-induced liquefaction and sliding case histories where SPT data and residual strength parameters have been measured. 1,600 40 Earthquake-induced liquefaction and sliding case histories where SPT data and residual strength parameters have been estimated. Construction-induced liquefaction and sliding case histories. 1,200 30 ` 20 800 Recommended residual strengths for use in the hybrid p-y model 400 0 0 4 8 12 16 20 10 0 24 Residual Undrained Shear Strength, Sr, kPa Residual Undrained Shear Strength, Sr, psf The residual shear strength is taken as the 33rd percentile of the residual strength correlation developed by Seed and Harder (1990) . This correlation is illustrated in Figure 3-37. In the original recommendations for the hybrid p-y curve, the residual undrained shear strength for soils less than 5 blows per foot was taken to be zero. Equivalent Clean Sand SPT Blowcount, (N1)60-cs Figure 3-37 Recommended Method for Computing Residual Shear Strength of Liquefied Soil for Use in Hybrid p-y Model The 33rd percentile for residual strength as a function of SPT blowcount is shown as the dashed gray line the figure above. The 33rd percentile of residual strength is determined by: Sur = 0 for (N1)60-cs –values less than 5 blows per foot Sur (psf) = 0.083467(N1)60-cs3 + 2.000777(N1)60-cs 2 - 12.642774(N1)60-cs + 90.689977 Sur is constant for (N1)60-cs greater than 16 bpf = 742.4853 psf The strain factor 50 is computed as a function of SPT blowcount using 110 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 0.0005 50 0.1537 e 0.229 N1 60cs 0.05 ...................................(3-77) Note that the lower and upper limits on 50 are 0.0005 and 0.05. The correlation of 50 with SPT blowcount is illustrated in Figure 3-38 0.06 0.05 0.04 50 0.03 0.02 0.01 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 (N1)60-cs Figure 3-38 Factor 50 as Function of SPT Blowcount There are four possible patterns for the over lapping of the dilative and residual p-y curves. These patterns are illustrated in Figure 3-39, with the residual curves shown in red and the dilative curve shown in blue. There are two patterns where there is one intersection point between the two curves. These two patterns are indicated by points 1 and 2 in the graph. There is one pattern in which the curves intersect at two points, indicated by points 3 and 4, and one pattern in which the dilative curve underlies the entirety of the residual curve. LPile computes the coordinates of the intersection points and includes them in the output report for the generated p-y curves. 111 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p No intersections Intersections at 2 and 3 4 3 Intersection at 2 2 Intersection at 1 1 y Figure 3-39 Possible Intersection Patterns of Residual and Dilative p-y Curves in Hybrid p-y Model The four following figures illustrate these four curve patterns. 14 12 Pile Diam., b = 0.3 m Depth, z = 4.0 m Eff. Unit Wt., ’ = 10 kN/m3 (N1)60-cs = 7 bpf Sur = 128.9 psf p, kN/m 10 8 6 Residual p 4 Dilative p Hybrid p 2 0 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 y, mm Figure 3-40 Example of Non-intersecting Curves 112 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 16 14 Pile Diam., b = 0.3 m Depth, z = 4.0 m Eff. Unit Wt., ’ = 10 kN/m3 (N1)60-cs = 6 bpf Sur = 104.9 psf 12 p, kN/m 10 8 y1i 6 Residual p 4 Dilative p Hybrid p 2 0 0 100 200 300 400 y, mm Figure 3-41 Example of Curves with One Intersection of Dilative and Residual Curves 10 9 8 Pile Diam., b = 0.3 m Depth, z = 0 m Eff. Unit Wt., = 10 kN/m3 (N1)60-cs = bpf Sur = 99.8 psf 7 p, kN/m 6 5 4 Residual p Dilative p 3 Hybrid p 2 1 0 0 50 100 150 200 250 y, mm Figure 3-42 Example of Curve with One Intersection of Dilative Curve and Residual Plateau 113 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 18 16 Pile Diam., b = 0.3 m Depth, z = 4.0 m Eff. Unit Wt., ’ = 10 kN/m3 (N1)60-cs = 7 bpf Sur = 128.9 psf 14 p, kN/m 12 10 8 6 Residual p Dilative p 4 Hybrid p 2 0 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 y, mm Figure 3-43 Example of Curve with Two Intersection Points 3-5-4 Modeling of Lateral Spread When liquefaction occurs in sloping soil layers, it is possible for the ground to develop large permanent deformations. This phenomenon is called lateral spreading. Lateral spreading may develop even though the ground surface may be nearly flat. If the free-field soil movements are greater than the pile displacements, the displaced soils will apply an additional lateral load to the piles. The magnitude and direction of the forces acting on the pile by soil movement is dependent on the relative displacement between the pile and soil. If the liquefaction causes the upper layer to become unstable and move laterally, a model recommended by Isenhower (1992) may be used to solve for the behavior of the pile. This method is described in Section 4-3. Other references on the topic of foundation subjected to lateral spreading are Ashford, et al. (2011) and California Department of Transportation (2011). 3-6 p-y Curves for Loess Soils 3-6-1 Background A procedure was formulated by Johnson, et al. (2006) for loess soil that includes degradation of the p-y curves by load cycling. The soil strength parameter used in the model is the cone tip resistance (qc) from cone penetration (CPT) testing. The p-y curve for lateral resistance with displacement is modeled as a hyperbolic relationship. Recommendations are presented for selection of the needed model 114 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock parameters, as well as a discussion of their effect. The p-y curves were obtained from backfitting of lateral analyses using the computer program LPile to the results of the load tests. 3-6-1-1 Description of Load Test Program Shafts were tested in pairs to provide reaction for each other. Both shafts used in the load test were fully instrumented. Load tests were performed on one pair of 30-inch diameter loaded statically, one pair of 42-inch diameter test shafts loaded statically, and one pair of 30-inch diameter test shafts loaded cyclically. Lateral loads were maintained at constant levels for load increments without inclinometer readings, and the hydraulic pressure supply to the hydraulic rams was locked off during load increments with inclinometer readings to eliminate creep of the deflected pile shape with depth while inclinometer readings were made. 13 and 15 load increments were used to load the 30-inch and 42 inch diameters pairs of static test piles, respectively, while both sets of static test piles were unloaded in four decrements. Six sets of inclinometer readings were performed for each static test pile, four of which occurred at load increments. Load increments and decrements for the static test shafts were sustained for approximately 5 minutes, with the exception of the load increments with inclinometer readings where the duration was approximately 20 minutes (this allowed for approximately 10 minutes for inclinometer measurements for each of the two test shafts in the pair). Lateral loads were applied to the 30-inch and 42-inch diameter static test shafts in approximately 10-kip and 15-kip increments, respectively. There were four load increments (noted as “A” through “D”) on the 30-inch diameter cyclic test shafts, with ten load cycles (N = 1 through 10) performed per load increment. The lateral load for each load cycle were sustained for only a few seconds with the exception of load cycles 1 and 10 which were sustained for approximately 15 to 20 minutes to allow time for the inclinometer readings to be performed. For load cycles 2 through 9, the duration for each load cycle was approximately 1 minute, 2 minutes, 3.5 minutes, and 6.5 minutes for load increments A though D, respectively, as a greater time was required to reach the larger loads. The load was reversed after each load cycle to return the top of pile to approximately the same location. 3-6-1-2 Soil Profile from Cone Penetration Testing A back-fit model of the pile behavior using the available soil strength data obtained (from both in-situ and laboratory tests) to the measured pile performance led to the conclusion that the CPT testing provided the best correlation. Furthermore, CPT testing can be easily performed in the loess soils being modeled and has become readily widely available. Three cone penetration tests were performed by the Kansas Department of Transportation at the test site location. A preliminary cone penetration test was performed in the general vicinity of the test shafts (designated as CPT-1). Two additional cone penetration tests were performed subsequent to the lateral load testing. A cone penetration test was performed between the 42-inch diameter static test shafts (Shafts 1 and 2) shortly after on the same day the lateral load test was performed on these shafts. A cone penetration test was performed between the 30-inch diameter static test shafts (Shafts 3 and 4) two days after the completion of the load test performed on these shafts. The locations of the cone penetration tests were a few feet from the test shafts. Given the nature of the soil conditions and the absence of a ground water table, it is reasonable to assume that the cone penetration tests were unaffected by any pore water pressure effects that may have been induced by the load testing. 115 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock An idealized profile of cone tip resistance with depth interpreted as an average from the cone penetration tests performed between the static test shafts is shown in Figure 3-44. This profile is considered representative of the subsurface conditions for all the test shaft locations. Note that it is most useful to break the idealized soil profile into layers wherein the cone tip resistance is either constant with depth or linearly varies with depth as these two conditions are easily accommodated by most lateral pile analyses software. The cone tip resistance is reduced by 50% at the soil surface, and allowed to increase linearly with depth to the full value at a depth of two pile diameters, as shown in Figure 3-44. This is done to account for the passive wedge failure mechanism exhibited at the ground surface that reduces the lateral resistance of the soil between the ground surface and a lower depth (assumed at two shaft diameters). Below a depth of two shaft diameters, the lateral resistance is considered as a flow around bearing failure mechanism. The idealized cone tip resistance values were correlated with depth with the ultimate lateral soil resistance (pu0) at corresponding depths. Reduced by 50% at surface 0 2-D = 5 ft for 30-inch Diam. Shafts 5 2-D = 7 ft for 42-inch Diam. Shafts Depth Below Grade (ft) 10 15 20 Used For Model 25 Between 30" A.L.T. (6/9/2005) 30 Between 42" A.L.T. (6/8/2005) CPT-1 (8/12/2004) 35 40 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 qc (ksf) qc, ksf Figure 3-44 Idealized Tip Resistance Profile from CPT Testing Used for Analyses. 3-6-2 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Loess 3-6-2-1 General Description of p-y Curves in Loess Procedures are provided to produce a p-y curve for loess, shown generically in Figure 345. The ultimate soil resistance (pu0) that can be provided by the soil is correlated to the cone tip resistance at any given elevation. Note that to account for the passive wedge failure mechanism exhibited at the ground surface, the cone tip resistance is reduced by 50% at the soil surface and allowed to return to the full value at a depth equal to two pile diameters. The initial modulus of 116 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock the p-y curve, Ei, is determined from the ultimate lateral soil reaction expressed on a per unit length of pile basis, pu, for the specified pile diameter, and specified reference displacement, yref. A hyperbolic relationship is used to compute the secant modulus of the p-y curve, Es, at any given pile displacement, y. The lateral soil reaction per unit pile length, p, for any given pile displacement is determined by the secant modulus at that displacement. Provisions for the degradation of the p-y curve as a function of the number of cycles loading, N, are incorporated into the relationship for ultimate soil reaction. The model is of a p-y curve that is smooth and continuous. This model is similar to the lateral behavior of pile in loess soil measured in load tests. 3-6-2-2 Equations of p-y Model for Loess The ultimate unit lateral soil resistance, pu0, is computed from the cone tip resistance multiplied by the cone bearing capacity factor, NCPT using puo NCPT qc .........................................................(3-78) p pu Ei Es y yref Figure 3-45. Generic p-y curve for Drilled Shafts in Loess Soils where NCPT is dimensionless, and pu0 and qc are in consistent units of (force/length2) The value of NCPT was determined from a best fit to the load test data. It is believed that NCPT is relatively insensitive to soil type as this is a geotechnical property determined by in-situ testing. The value of NCPT derived from the load test data is N CPT 0.409 ........................................................(3-79) 117 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The ultimate lateral soil reaction, pu, is computed by multiplying the ultimate unit lateral soil resistance by the pile diameter, b, and dividing by an adjustment term to account for cyclic loading. The adjustment term for cyclic loading takes into account the number of cycles of loading, N, and a dimensionless constant, CN. pu puo b ....................................................(3-80) 1 CN log N where: b is the pile diameter in any consistent unit of length, CN is a dimensionless constant, N is the number of cycles of loading (1 to 10), and pu is in units of (force/length). CN was determined from a best fit of cyclic degradation for two 30-inch diameter test shafts subjected to cyclic loading. CN is C N 0.24 ...........................................................(3-81) The cyclic degradation term (the denominator of Equation 3-80) equals 1 for N = 1 (initial cycle, or static load) and equals 1.24 for N = 10. The value of CN has a direct effect on the amount of cyclic degradation to the p-y curve (i.e., a greater value of CN will allow greater degradation of the p-y curve, resulting in a smaller pu). Note that the degradation of the ultimate soil resistance per unit length of shaft parameter will also have the desired degradation effect built into the computation of the p-y modulus values. A parameter is needed to define the rate at which the strength develops towards its ultimate value (pu0). The reference displacement, yref, is defined as the displacement at which the tangent to the p-y curve at zero displacement intersects the ultimate soil resistance asymptote (pu), as shown in Figure 3-45. The best fit to the load test data was obtained with the following value for reference displacement. yref = 0.117 inches = 0.0029718 meters .................................. (3-82) Note that the suggested value for the reference displacement provided the best fit to the piles tested at a single test site in Kansas for a particular loess formation. Unlike the ultimate unit lateral resistance (pu0), it is believed that the rate at which the strength is mobilized may be sensitive to soil type. Thus, re-evaluation of the reference displacement parameter is recommended when performing lateral analyses for piles in different soil conditions because this parameter is likely to have a substantial effect on the resulting pile deflections. The effect of the reference displacement is proportional to pile performance that is a larger value of yref will allow for larger pile head displacements at a given lateral load. The initial modulus, Ei, is defined as the ratio of the ultimate lateral resistance expressed on a per unit length of pile basis over the reference displacement. 118 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Ei pu ........................................................... (3-83) yref A secant modulus, Es, is determined for any given displacement, y, by the following hyperbolic relationship of the initial modulus expressed on a per unit length of pile basis and a hyperbolic term ( yh ) which is in turn a function of the given displacement (y), the reference displacement (yref), and a dimensionless correlation constant (a). Es y yh y ref Ei ......................................................... (3-84) 1 yh 1 a e y ref y .............................................. (3-85) a 0.10 ............................................................(3-86) where Es and Ei are in units of force/length2, and a and yh are dimensionless. The constant a was found from a best fit to the load test data. Note that the constant a primarily affects the secant modulus at small displacements (say within approximately 1 inch or 25 mm), and is inversely proportional to the stiffness response of the p-y curve (i.e., a larger value of a will reduce the mobilization of soil resistance with displacement). Combining the two equations above, one obtains y yh y ref 1 0.1e y ref y .............................................(3-87) The modulus ratio (secant modulus over initial modulus, Es/Ei) versus displacement used for p-y curves in loess is shown in Figure 3-46. Note that the modulus ratio is only a function of the hyperbolic parameters of the constant (a) and the reference displacement (yref), thus the curve presented is valid for all pile diameters and cone tip bearing values tested. 119 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 1.0 0.9 a = 0.1 0.8 0.7 0.6 Es Ei 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 0.001 0.01 0.1 1.0 10 100 y yref Figure 3-46 Variation of Modulus Ratio with Normalized Lateral Displacement Both the initial modulus and the secant modulus are proportional related to the pile diameter because the ultimate soil resistance is proportional to a given pile size, as was shown in Equation 3-80. It follows that the lateral response will increase in proportion to the pile diameter. For a given pile displacement, the lateral soil resistance per unit length of pile is a product of the pile displacement and the corresponding secant modulus at that displacement. p ES y ........................................................... (3-88) where: Es is the secant modulus in units of force/length2, and y is the lateral pile displacement. Several p-y curves obtained from the model described above is presented in Figure 3-47 for the 30-inch diameter shafts, and Figure 3-48 for the 42-inch diameters shafts. Note that there are three sets of curves presented for each shaft diameter which correspond to the cone tip resistance values of 11 ksf, 22 ksf, and 100 ksf (as was shown in Figure 3-44). These p-y curves were used in the LPile analyses presented later. 120 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 9,000 8,000 7,000 p, lb/in. . 6,000 11 ksf 5,000 22 ksf 100 ksf 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 y , inches Figure 3-47 p-y Curves for the 30-inch Diameter Shafts 14,000 12,000 p, lb/in. . 10,000 11 ksf 8,000 22 ksf 100 ksf 6,000 4,000 2,000 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 y , inches Figure 3-48 p-y Curves and Secant Modulus for the 42-inch Diameter Shafts. The static p-y curves shown in Figure 3-47 and 3-48 were degraded with load cycle number (N) for use in the cyclic load analyses. Figure 3-49 presents the cyclic p-y curve generated for the analyses of the 30-inch diameter shafts at the cone tip resistance value of 22 ksf. 121 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 2,000 1,800 1,600 p, lb/in. . 1,400 N= 1 1,200 N= 5 1,000 N = 10 800 600 400 200 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 y , inches Figure 3-49 Cyclic Degradation of p-y Curves for 30-inch Shafts 3-6-2-3 Step-by-Step Procedure for Computing p-y Curves A step-by-step procedure to generate p-y curves in using the model follows. 1. Develop an idealized profile of cone tip resistance with depth that is representative of the local soil conditions. It is most useful to subdivide the soil profile into layers where the cone tip resistance is either constant with depth or varies linearly with depth. 2. Reduce the cone tip resistance by 50% at the soil surface, and allowed the value to return to the full measured value at a depth equal to two pile diameters. Linear interpolation may be used between the surface and the depth of two pile diameters. 3. For each soil layer, compute the ultimate soil resistance from the cone tip resistance in accordance with Equation 3-78 for both the top and the bottom of each layer. 4. Multiply the ultimate soil resistance by the pile diameter to obtain the ultimate soil reaction per unit length of shaft (pu). For cyclic analyses, pu may be degraded for a given cycle of loading (N) in accordance with Equation 3-80. 5. Select a reference displacement (yref) that will represent the rate at which the resistance will develop. 6. Determine the initial modulus (Ei) in accordance with Equation 3-83. 7. Select a number of lateral pile displacements (y) for which a representative p-y curve is to be generated. 8. Determine the secant modulus (Es) for each of the displacements selected in Step 7 in accordance with Equations 3-84 and 3-85. 9. Determine the soil resistance per unit length of pile (p) for each of the displacements selected in Step 7 in accordance with Equation 3-88. 122 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-6-2-4 Limitations on Conditions for Validity of Model The p-y curve for static loading was based on best fits of data from full-scale load tests on 30-inch and 42-inch diameter shafts installed in a loess with average cone tip resistance values ranging from 20 to 105 ksf (960 to 5,000 kPa). Caution is advised when extrapolating the static model formulation for shaft diameters or soil types and/or strengths outside these limits. In addition, the formulation for the cyclic degradation model parameters are based on load tests with only ten cycles of loading (N = 1 to 10) obtained at four different load increments on an additional two 30-inch diameter shafts. Caution is thus also warranted when extrapolating the cyclic model to predict results beyond 10 cycles of load (N > 10), particularly as the magnitude of loading increases. 3-7 p-y Curves for Cemented Soils with Both Cohesion and Friction 3-7-1 Background The methods for p-y curves that were presented previously were for soils that can be characterized as either as purely cohesive or purely cohesionless. There are currently no generally accepted recommendations for developing p-y curves for soils that have both cohesion due to cementation and frictional characteristics. Among the reasons for the limitation on soil characteristics are the following. Firstly, in foundation design where the p-y analysis has been used, the characterization of the soil by either a value of cohesion or friction has been used, but not both. Secondly, the major experiments on which the p-y predictions have been based have been performed in soils that can be described by either cohesion (c) or friction (. However, there are numerous occasions when it is desirable, and perhaps necessary, to describe the characteristics of the soil with both cohesion due to cementation and friction. One example of the need to have predictions for p-y curves for cemented c- soils is when piles are used to stabilize a slope. A detailed explanation of the analysis procedure is presented in Chapter 6. It is well known that most of the currently accepted methods of analysis of slope stability characterize the soils in terms of c and for long-term, drained conditions. Therefore, it is inconsistent, and potentially unsafe or unconservative, to assume that the soil is characterized by either c or alone. There are other instances in the design of piles under lateral loading where it is desirable to have methods of prediction for p-y curves for c- soils. The shear strength of unsaturated, cohesive soils generally is represented by strength components of both c and . In many practical cases, however, there is the likelihood that the soil deposit might become saturated because of seasonal rainfall and subsequent rise of the ground water table. However, there could well be times when the ability to design for dry seasons is needed. Cemented soils are frequently found in subsurface investigations. Some comments for the response of laterally loaded piles in calcareous soils were presented by Reese (1988). It is apparent that cohesion from the cementation will increase the shearing resistance significantly, particularly for soils near the ground surface. 123 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock It should be noted that the procedure presented here has been revised from versions of LPile earlier than data format 8 (LPile 2015). 3-7-2 Recommendations for Computing p-y Curves The following procedure for computing p-y curves cemented c- soils is for short-term static loading and for cyclic loading. The shape of the resulting p-y curve is illustrated in Figure 3-50. The p-y curve is composed of four segments; an initial slope between the origin and point k defined by the slope k x, a parabolic section between points k and m, a straight line section between points m and u and a flat section defined past point u. As will be noted, the suggested procedure follows closely the procedure that which was recommended earlier for p-y curves in sand. p m pm k pk yk ym u pu kx yu y b/60 3b/80 Figure 3-50 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curves for c- Soil Conceptually, the ultimate soil resistance, pu, is taken as the passive soil resistance acting on the face of the pile in the direction of the horizontal movement, plus any sliding resistance on the sides of the piles, less any active earth pressure force on the rear face of the pile. The force from active earth pressure and the sliding resistance will generally be small compared to the passive resistance, and will tend to cancel each other out. Evans and Duncan (1982) recommended an approximate equation for the peak resistance of c- soils as: p p b C p hb .................................................... (3-89) where p = passive pressure including the three-dimensional effect of the passive wedge (F/L2) b = pile width (L), The Rankine passive pressure for a wall of infinite length (F/L2), 124 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock h x tan 2 45 2 c tan 45 ................................ (3-90) 2 2 = effective unit weight of soil (F/L3), x = depth at which the passive resistance is considered (L), = angle of internal friction (degrees), c = cohesion (F/L2), and Cp = dimensionless modifying factor to account for the three-dimensional effect of the passive wedge at the ground surface. The modifying factor Cp can be divided into two terms: Cp to represent the frictional contribution to Equation 3-89 and Cpc to represent the cohesive contribution to Equation 3-89. Equation 3-89 can then be written as Equation 3-91 as p C p x tan 2 45 C pc c tan 45 b ........................... (3-91) 2 2 Equation 3-91 will be rewritten as p A p pc ........................................................ (3-92) where A can be found for static and cyclic loading from Figure 3-28 on page 106. The frictional component, p, is the smaller of ps or pd. pu = min[ps, pd] .................................................... (3-93) The terms ps and pd are defined by the two equations below: K x tan sin tan ps x 0 (b x tan tan ) .................... (3-94) tan( ) cos tan( ) K 0 x tan (tan sin tan ) K Ab pd K A b x (tan8 1) K 0 b x tan tan 4 ............................ (3-95) The cohesive component, pc, is the smaller of pcs or pcd. pc min pcs , pcd ................................................... (3-96) where: J pcs 3 x x c b .............................................. (3-97) c b 125 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock where J is a dimensionless constant equal to 0.5 and pcd 9 c b .......................................................... (3-98) Furthermore, it is assumed that the contribution of cohesion due to cementation is lost as the load-transfer curve transitions from the peak value to the residual value, so the strength of the residual curve is due to the frictional component only and is p A pu ........................................................... (3-99) 3-7-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Soils with Both Cohesion and Internal Friction To develop the p-y curves, the procedures described earlier for sand by Reese et al (1974) will be used because the stress-strain behavior of c- soils are believed to be closer to the stressstrain curve of cohesionless soil than for cohesive soil. The following procedures are used to develop the p-y curves for soils with both cohesion and internal friction. 1. Compute yu by the following equation: yu 2. 3b ...........................................................(3-100) 80 Compute pu for static loading using pu As pu ...................................................... (3-101) or for cyclic loading using pu Ac pu ...................................................... (3-102) Use the appropriate value of As or Ac from Figure 3-28 on page 106 for the particular non-dimensional depth (x/b) and type of loading. 3. Compute ym as ym 4. b ......................................................... (3-103) 60 Compute pm for static by the following equation pm Bs pu puc .................................................. (3-104) or for cyclic loading by pm Bc pu puc ................................................. (3-105) 126 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Use the appropriate value of Bs or Bc from Figure 3-29 on page 107 for the particular nondimensional depth and for either the static or cyclic case. Use the appropriate equations for pu and puc. The two straight-line portions of the p-y curve, beyond the point where y is equal to b/60, can now be established. 5. Establish the initial straight-line portion of the p-y curve, p k x y ....................................................... (3-106) The value of k for Equation 3-106 may be found from the following equation and by reference to Figure 3-51. k k c k ....................................................... (3-107) For example, if c is equal to 0.2 tsf and is equal to 35 degrees for a layer of c- soil above the water table, the recommended kc is 350 pci and k is 80 pci, yielding a value of k of 430 pci. 2,000 1,500 kc (static) 400,000 kc (cyclic) 1,000 300,000 200,000 k (submerged) 500 100,000 k (above water table) 0 Initial Modulus k, kN/m3 Initial Modulus k, pci 500,000 0 c tsf 0 1 2 3 4 deg. 0 28 32 36 40 c kPa 0 96 192 287 383 Figure 3-51 Representative Values of k for c- Soil 6. The parabolic section of the p-y curve will be computed from p S y1 / n ........................................................ (3-108) 127 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock To fit the parabola between points k and m, compute the parameters m, n, S, and yk using the following expressions: a. Compute the slope of the line between point m and point u by, m pu pm ...................................................... (3-109) yu y m b. Compute the power of the parabolic section using n pm ........................................................ (3-110) m ym c. Compute the coefficient S using S pm ym 1/ n ....................................................... (3-111) d. Compute displacement, yk, at the intersection of the initial slope defined by kx and the parabolic section using n S n1 ...................................................... (3-112) yk k x e. Compute points along the parabolic section by using p S y1 / n ........................................................ (3-108) Note: The step-by-step procedure is outlined above as if there is an intersection between the initial straight-line portion of the p-y curve and the parabolic portion of the curve at point k. However, in some instances there may be no intersection with the parabola if the initial slope is sufficiently small, as drawn below. 128 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p m ym, pm u yu, pu y Figure 3-52 Possible Intersection Points of Initial Tangent Line Along p-y Curve 3-7-4 Discussion An example of p-y curves was computed for cemented c- soils for a pile with a diameter of 12 inches (0.3 meters). The c value is 400 psf (20 kPa) and a value is 35 degrees. The unit weight of soil is 115 pcf (18 kN/m3). The p-y curves were computed for depths of 39.4 in. (1 m), 78.7 in. (2 m), and 118.1 inches (3 meters). The p-y curves computed by using the simplified procedure are shown in Figure 3-53. As can be seen, the ultimate resistance of the soil, based in the model procedure, is higher than from the simplified procedure. Both of the p-y curves show a peak strength, then drop to a residual strength at large deflections, as is expected. Because of a lack of experimental data to calibrate the soil resistance, based on the model procedure, it is recommended that the simplified procedure be used at present. The point was made clearly at the beginning of this section that data are unavailable from a specific set of experiments that was aimed at the response of c- soils. Such experiments would have made use of instrumented piles. Further, little information is available in the literature on the response of piles under lateral loading in such soils where response is given principally by deflection of the pile at the point of loading. Data from one such experiment, however, was available and the writers have elected to use that data in an example to demonstrate the use of this criterion. A comparison was made there between results from experiment and results from computations. The reader will note that the procedure presented above does not reflect a severe loss of soil resistance under cyclic loading that is a characteristic for clays below a free-water surface. Rather, the procedures described above are for a material that is primarily granular in nature, which does not reflect such loss of resistance. Therefore, if a c- soil has a very low value of and a relatively large value of c, the user is advised to ignore the and to use the recommendations for p-y curves for clay. Further, a relatively large factor of safety is recommended in any case, and a field program of testing of prototype piles is certainly in order for jobs that involve any large number of piles. 129 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 1,000 1m 2m 800 p, kN/meter 3m 600 400 200 0 0 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.01 0.012 0.014 y, meters Figure 3-53 p-y Curves for Cemented c- Soil 3-8 p-y Curves for Rock 3-8-1 Introduction The use of deep foundations in rock is frequently required for support of bridges, transmission towers, or other structures that sustain lateral loads of significant magnitude. Because the rock must be drilled in order to make the installation, drilled shafts are commonly used. However, a steel pile could be grouted into the drilled hole. In any case, the designer must use appropriate mechanics to compute the bending moment capacity and the variable bending stiffness EI. Experimental results show conclusively that the EI must be reduced, as the bending moment increases, in order to achieve a correct result (Reese, 1997). In some applications, the axial load is negligible so the penetration is controlled by lateral load. The designer will wish to initiate computations with a relatively large penetration of the pile into the rock. After finding a suitable geometric section, the factored loads are employed and computer runs are made with penetration being gradually reduced. The ground-line deflection is plotted as a function of penetration and a penetration is selected that provides adequate security against a sizable deflection of the bottom of the pile. Concepts are presented in the following section that from the basis of computing the response of piles in rock. The background for designing piles in rock is given and then two sets of criteria are presented in this section, one for vuggy limestone and the other for weak rock. 130 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Much of the presentation follows the paper by Reese (1997) and more detail will be found in that paper. The secondary structure of rock is an overriding feature is respect to its response to lateral loading. Thus, an excellent subsurface investigation is assumed prior to making any design. The appropriate tools for investigating the rock are employed and the Rock Quality Designation (RQD) should be taken, along with the compressive strength of intact specimens. If possible, sufficient data should be taken to allow the computation of the Rock Mass Rating (RMR). Sometimes, the RQD is so low that no specimens can be obtained for compressive tests. The performance of pressuremeter tests in such instances is indicated. If investigation shows that there are soil-filled joints or cracks in the rock, the procedures suggested herein should not be used but full-scale testing at the site is recommended. Furthermore, full-scale testing may be economical if a large number of piles are to be installed at a particular site. Such field testing will add to the data bank and lead to improvements in the recommendations shown below, which are to be considered as preliminary because of the meager amount of experimental data that is available. In most cases of design, the deflection of the drilled shaft (or other kind of pile) will be so small that the ultimate strength pur of the rock is not developed. However, the ultimate resistance of the rock should be predicted in order to allow the computation of the lateral loading that causes the failure of the pile. Contrary to the predictions of p-y curves for soil, where the unit weight is a significant parameter, the unit weight of rock is neglected in developing the prediction equations that follow. While a pile may move laterally only a small amount under the working loads, the prediction of the early portion of the p-y curve is important because the small deflections may be critical in some designs. Most intact rocks are brittle and develop shear planes at low shear strains. This fact leads to an important concept about intact rock. The rock is assumed to fracture and lose strength under small values of deflection of a pile. If the RQD of a stratum of rock is zero, or has a low value, the rock is assumed to have already fractured and, thus, will deflect without significant loss of strength. The above concept leads to the recommendation of two sets of criteria for rock, one for strong rock and the other for weak rock. For the purposes of the presentations herein, strong rock is assumed to have a compressive strength of 6.9 MPa (1,000 psi) or above. The methods of predicting the response of rock is based strongly on a limited number of experiments and on correlations that have been presented in technical literature. Some of the correlations are inexact; for example, if the engineer enters the figure for correlation between stiffness and strength with a value of stiffness from the pressuremeter, the resulting strength can vary by an order of magnitude, depending on the curve that is selected. The inexactness of the necessary correlations, plus the limited amount of data from controlled experiments, mean that the methods for the analysis of piles in rock must be used with a good deal of both judgment and caution. For major projects, full-scale load testing is recommended to verify foundation performance and to evaluate the efficiency of proposed construction methods. 131 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-8-2 Descriptions of Two Field Experiments 3-8-2-1 Islamorada, Florida An instrumented drilled shaft (bored pile) was installed in vuggy limestone in the Florida Keys (Reese and Nyman, 1978) and was tested under lateral loads. The test was performed for gaining information for the design of foundations for highway bridges. Considerable difficulty was encountered in obtaining properties of the intact rock. Cores broke during excavation and penetrometer tests were misleading because of the presence of vugs or could not be performed. It was possible to test two cores from the site. The small discontinuities in the outside surface of the specimens were covered with a thin layer of gypsum cement in an effort to minimize stress concentrations. The ends of the specimens were cut with a rock saw and lapped flat and parallel. The specimens were 149 mm (5.88 in.) in diameter and with heights of 302 mm (11.88 in.) for Specimen 1 and 265 mm (10.44 in.) for Specimen 2. The undrained shear strength values of the specimens were taken as one-half the unconfined compressive strength and were 1.67 MPa (17.4 tsf) and 1.30 MPa (13.6 tsf) for Specimens 1 and 2, respectively. The rock at the site was also investigated by in-situ-grout-plug tests (Schmertmann, 1977). In these tests, a 140-mm (5.5 in.) hole was drilled into the limestone, a high-strength steel bar was placed to the bottom of the hole, and a grout plug was cast over the lower end of the bar. The bar was pulled until failure occurred, and the grout was examined to see that failure occurred at the interface of the grout and limestone. Tests were performed at three borings, and the results shown in Table 3-8 were obtained. The average of the eight tests was 1.56 MPa (226 psi or 16.3 tsf). However, the rock was stronger in the zone where the deflections of the drilled shaft were greatest and a shear strength of 1.72 MPa (250 psi or 18.0 tsf) was selected for correlation. Table 3-8 Results of Grout Plug Tests by Schmertmann (1977) Depth Range meters 0.76-1.52 2.44-3.05 feet 2.5-5.0 8.0-10.0 5.49-6.10 18.0-20.0 Ultimate Resistance MPa psf tsf 2.27 331 23.8 1.31 190 13.7 1.15 167 12.0 1.74 253 18.2 2.08 301 21.7 2.54 368 26.5 1.31 190 13.7 1.02 149 10.7 The bored pile was 1,220 mm (48 in.) in diameter and penetrated 13.3 m (43.7 ft) into the limestone. The overburden of fill was 4.3 m (14 ft) thick and was cased. The load was applied at 3.51 m (11.5 ft) above the limestone. A maximum horizontal load of 667 kN (75 tons) was 132 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock applied to the pile. The maximum deflection at the point of load application was 18.0 mm (0.71 in.) and at the top of the rock (bottom of casing) it was 0.54 mm (0.0213 in.). While the curve of load versus deflection was nonlinear, there was no indication of failure of the rock. Other details about the experiment are shown in the Case Studies that follow. 3-8-2-2 San Francisco, California The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) performed lateral-load tests of two drilled shafts near San Francisco (Speer, 1992). The results of these unpublished tests have been provided by courtesy of Caltrans. Two exploratory borings were made into the rock and sampling was done with a NWD4 core barrel in a cased hole with a diameter of 102 mm (4 in.). A 98-mm (3.88-in.) tri-cone roller bit was used in drilling. The sandstone was medium to fine grained with grain sizes from 0.1 to 0.5 mm (0.004 to 0.02 in.), well sorted, and thinly bedded with thickness of 25 to 75 mm (1 to 3 in.). Core recovery was generally 100%. The reported values of RQD ranged from zero to 80, with an average of 45. The sandstone was described by Speer (1992) as moderately to very intensely fractured with bedding joints, joints, and fracture zones. Pressuremeter tests were performed and the results were scattered. The results for moduli values of the rock are plotted in Figure 3-54. The dashed lines in the figure show the average values that were used for analysis. Correlations of RQD to modulus reduction ratio shown in Figure 3-55 and the correlation of rock strength and modulus shown in Figure 3-56 were employed in developing the correlation between the initial stiffness from Figure 3-54 and the compressive strength, and the values were obtained as shown in Table 3-9. Initial Modulus, Eir, MPa 0 800 400 1,200 1,600 2,000 0 2 186 MPa Depth , meters 4 3.9 m 645 MPa 6 8 8.8 m 10 1,600 MPa 12 Figure 3-54 Initial Moduli of Rock Measured by Pressuremeter for San Francisco Load Test 133 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 1.2 Modulus Reduction Ratio Emass/Ecore 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 ? ? ? 0.0 0% 25% 50% 75% 100% Rock Quality Designation (RQD), % Figure 3-55 Modulus Reduction Ratio versus RQD (Bienawski, 1984) Two drilled shafts, each with diameters of 2.25 m (7.38 ft), and with penetrations of 12.5 m (41 ft) and 13.8 m (45 ft), were tested simultaneously by pulling the shafts together. Lateral loading was applied using hydraulic rams acting on high-strength steel bars that were passed through tubes, transverse and perpendicular to the axes of the shafts. Lateral load was measured using electronic load cells. Lateral deflections of the shaft heads were measured using displacement transducers. The slope and deflection of the shaft heads were obtained by readings from slope indicators. The load was applied in increments at 1.41 m (4.6 ft) above the ground line for Pile A and 1.24 m (4.1 ft) for Pile B. The pile-head deflection was measured at slightly different points above the rock line, but the results were adjusted slightly to yield equivalent values for each of the piles. Other details about the loading-test program are shown in the case studies that follow. Table 3-9 Values of Compressive Strength at San Francisco Depth Interval Compressive Strength m ft MPa psi 0.0 to 3.9 0.0 to 12.8 1.86 270 3.9 to 8.8 12.8 to 28.9 6.45 936 below 8.8 below 28.9 16.0 2,320 The rock below 8.8 m (28.9 ft) is in the range of strong rock, but the rock above that depth will control the lateral behavior of the drilled shaft. 134 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock (MPa) 10 1,000 Ra us 50 0 100 ul 00 0 tio Very Low Low Medium High Very High 1, Rock Strength Classification (Deere) 100 M od 1 0 20 0 10 100,000 10 Upper and Middle Chalk (Hobbs) Concrete (MPa) Steel Young’s Modulus – psi 106 Gneiss 1.0 Grades of Chalk (Ward et al.) I II III 0.1 Limestone, Dolomite Basalt and other Flow Rocks Lower Chalk (Hobbs) Deere 10,000 Sandstone 1,000 Trias (Hobbs) IV V Keuper 100 Black Shale 0.01 Grey Shale Hendron, et al. 10 Medium 0.001 Stiff Very Stiff Hard 0.01 0.1 Clay 1 1.0 10 100 Uniaxial Compressive Strength – psi 103 Figure 3-56 Engineering Properties for Intact Rocks (after Deere, 1968; Peck, 1976; and Horvath and Kenney, 1979) 135 1,000 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-8-3 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Vuggy Limestone The p-y curve recommended for strong rock (vuggy limestone), with compressive strength of intact specimens larger than 6.9 MPa (1,000 psi), shown in Figure 3-57. If the rock increases in strength with depth, the strength at the top of the stratum will normally control. Cyclic loading is assumed to cause no loss of resistance. As shown in the Figure 3-57, load tests are recommended if deflection of the rock (and pile) is greater than 0.0004b and brittle fracture is assumed if the lateral stress (force per unit length) against the rock becomes greater than half the diameter times the compressive strength of the rock. The p-y curve shown in Figure 3-57 should be employed with caution because of the limited amount of experimental data and because of the great variability in rock. The behavior of rock at a site could be controlled by joints, cracks, and secondary structure and not by the strength of intact specimens. Perform proof test if deflection is in this range p pu = b su Assume brittle fracture if deflection is in this range Es = 100su Es = 2000su NOT TO SCALE y 0.0004b 0.0024b Figure 3-57 Characteristic Shape of p-y Curve in Strong Rock 3-8-4 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Weak Rock The p-y curve that is recommended for weak rock is shown in Figure 3-58. The expression for the ultimate resistance pur for rock is derived from the mechanics for the ultimate resistance of a wedge of rock at the top of the rock. 136 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock p Mir pur y yA Figure 3-58 Sketch of p-y Curve for Weak Rock (after Reese, 1997) x pur r qurb1 1.4 r for xr 3b .................................... (3-113) b pur 5.2 r qurb for xr 3b .......................................... (3-114) where: qur = compressive strength of the rock, usually lower-bound as a function of depth, r = strength reduction factor, b = diameter of the pile, and xr = depth below the rock surface. The assumption is made that fracturing will occur at the surface of the rock under small deflections, therefore, the compressive strength of intact specimens is reduced by multiplication by r to account for the fracturing. The value of r is assumed to be 1.0 at RQD of zero and to decrease linearly to a value of one-third for an RQD value of 100%. If RQD is zero, the compressive strength may be obtained directly from a pressuremeter curve, or approximately from Figure 3-56, by entering with the value of the pressuremeter modulus. r 1 2 RQD% ................................................ (3-115) 3 100% 137 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock If one were to consider a strip from a beam resting on an elastic, homogeneous, and isotropic solid, the initial modulus Mir (pi divided by yi) in Figure 3-58 may be shown to have the following value (using the symbols for rock). 3 Mir kir Eir ..................................................... (3-116) where Eir = the initial modulus of the rock, and kir = dimensionless constant defined by Equation 3-117. Equations 3-116 and 3-117 for the dimensionless constant kir are derived from data available from experiment and reflect the assumption that the presence of the rock surface will have a similar effect on kir as was shown for pur for ultimate resistance. 400 xr kir 100 for 0 xr 3b ..................................... (3-117) 3b kir = 500 for xr > 3b ................................................ (3-118) With guidelines for computing pur and Mir, the equations for the three branches of the family of p-y curves for rock in Figure 3-57 can be presented. The equation for the straight-line, initial portion of the curves is given by Equation 3-119 and for the other branches by Equations 3-121 through 3-120. p M ir y for y y A ...............................................(3-119) yrm = rm b .........................................................(3-120) p p ur 2 y y rm 0.25 for y A y , y < 16yrm, and p pur ......................(3-121) p pur for y > 16yrm ................................................(3-122) where rm = a constant, typically ranging from 0.0005 to 0.00005 that serves to establish the upper limit of the elastic range of the curves using Equation 3-120. The constant rm is analogous to 50 used for p-y curves in clays. The stress-strain curve for the uniaxial compressive test may be used to determine rm in a similar manner to that used to determined 50. The notation used here for Mir and rm differs from that used in Reese (1997). The notation was changed to improve the clarity of the presentation. 3 138 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The value of yA is found by solving for the intersection of Equations 3-119 and 3-121, and the solution is presented in Equation 3-123. pur y A 0.25 2 y rm M ir 1.333 .............................................(3-123) As shown in the case studies that follow, the equations from weak rock predict with reasonable accuracy the behavior of single piles under lateral loading for the two cases that are available. An adequate factor of safety should be employed in all cases. The equations are based on the assumption that p is a function only of y. This assumption appears to be valid if loading is static and resistance is only due to lateral stresses. However, O’Neill (1996) noted that in large diameter drilled shafts, rotational moment is resisted in the vertical shear couple produced by the vertical shear stresses caused by the rotation of the pile. In rock, this effect could be significant, especially for small deflections, if the diameter of the pile is large. 3-8-5 Case Histories for Drilled Shafts in Weak Rock 3-8-5-1 Islamorada The drilled shaft was 1.22 m (48 in.) diameter and penetrated 13.3 m (43.7 ft) into limestone. A layer of sand over the limestone was retained by a steel casing, and the lateral load was applied at 3.51 m (11.5 ft) above the surface of the rock. A maximum lateral load of 667 kN (150 kips) was applied and the measured curve of load versus deflection was nonlinear. Values of the strengths of the concrete and steel were unavailable and the bending stiffness of the gross section was used for the initial solutions. The following values were used to compute the p-y curves: qur = 3.45 MPa (500 psi), r = 1.0, (RQD = 0%) Eri = 7,240 MPa (1.05 106 psi), rm = 0.0005, b = 1.22 m (48 in.), L = 15.2 m (50 ft), and EI = 3.73 106 kN-m2 (1.3 109 ksi). A comparison of pile-head deflection curves from experiment and from analysis is shown in Figure 3-59. Excellent agreement between the elastic EI and experiment and is found for loading levels up to about 350 kN (78.7 kips), where sharp change in the load-deflection curve occurs. Above that level of loading, nonlinear EI is required to match the experimental values reasonably well. Curves giving deflection and bending moment as a function of depth were computed for a lateral load of 334 kN (75 kips), one-half of the ultimate lateral load, and are shown in Figure 360. The plotting is shown for limited depths because the values to the full length are too small to 139 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock plot. The stiffness of the rock, compared to the stiffness of the pile, is reflected by a total of 13 points of zero deflection over the length of the pile of 15.2 meters (50 ft). However, for the data employed here, the pile will behave as a long pile through the full range of loading. 800 EI = 37.3105 kN-m2 EI = 5.36105 kN-m2 EI = 6.23105 kN-m2 Lateral Load, kN 600 EI = 7.46105 kN-m2 EI = 9.33105 kN-m2 400 EI = 12.4105 kN-m2 200 Analysis with Elastic EI Analysis with Reduced EI Measured in Load Test 0 0 10 5 15 20 Groundline Deflection, mm Figure 3-59 Comparison of Experimental and Computed Values of Pile-Head Deflection, Islamorada Test (after Reese, 1997) Values of EI were reduced gradually where bending moments were large to obtain deflections that would agree fairly well with values from experiment. Values of lateral deflection and bending moment versus depth are shown in Figure 3-60. The largest moment occurs close to the top of rock, in the zone of about 2.5 m (8.2 ft) to 4.5 meters (14.8 ft). The following values of load and bending stiffness were used in the analyses: 350 kN and below 3.73106 kN-m2; 400 kN, 1.24106 kN-m2; 467 kN, 9.33105 kN-m2; 534 kN, 7.46105 kN-m2; 601 kN, 6.23105 kNm2; and 667 kN, 5.36105 kN-m2. The computed bending moment curves were studied and reductions were only made where the bending stiffness was expected to be in the nonlinear range. The lowest value of EI that was used is believed to be roughly equal to that for the fully cracked section. The decrease in slope of the curve of yt versus Pt at Islamorada can reasonably be explained by reduction in values of EI. The analysis of the tests at Islamorada gives little guidance to the designer of piles in rock except for early loads. A study of the testing at San Francisco that follows is more instructive. 3-8-5-2 San Francisco The value of krm used in the analyses was 0.00005. For the beginning loads the value used for EI was 35.15106 kN-m2 (12.25109 ksi, E=28.05106 kPa (4.07106 psi); I = 1.253 m4 (3.01105 in4)). The nominal bending moment capacity Mnom was computed to be 17,740 m-kN 140 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock (1.57105 in-kips) and values of EI were computed as a function of bending moment. Data from Speer (1992) gave the following properties of the cross section: compressive strength of the concrete was 34.5 MPa (5,000 psi), tensile strength of the rebars was 496 MPa (72,000 psi), there were 40 bars with a diameter of 43 mm (1.69 in.), and cover thickness was 0.18 m (7.09 in.). Bending Moment, M, kN-m 400 0 0 400 800 1,200 M Depth, meters 2 y Rock Surface 4 6 8 1 0 1 2 3 Lateral Deflection, y, mm Figure 3-60 Computed Curves of Lateral Deflection and Bending Moment versus Depth, Islamorada Test, Lateral Load of 334 kN (after Reese, 1997) The data on deflection as a function of loads showed that the two piles behaved about the same for the beginning loads but the curve for Pile B exhibited a large increase in pile-head deflection at the largest load. The experimental curve for Pile B shown by the heavy solid line in Figure 3-61 suggests that a plastic hinge developed at the ultimate bending moment of 17,740 mkN (157,012 in-kips). Consideration was given to the probable reduction in the values of EI with increasing load and three methods were used to predict the reduced values. The three methods were: the analytical method as presented in Chapter 4, the approximate method of the American Concrete Institute (ACI 318) which does not account for axial load and may be used here; and the experimental method in which EI is found by trial-and-error computations that match computed and observed deflections. The plots of the three methods are shown in Figure 3-62 and all three curves show a sharp decrease in EI with increase in bending moment. For convenience in the computations, the value of EI was changed for the entire length of the pile but errors in using constant values of EI in the regions of low values of M are thought to be small. 141 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The computed and measured lateral load versus pile-head deflection curves are shown in Figure 3-61. The computed load-deflection curve computed using EI values derived from the load test agrees well with the load test curve, but the computed load-deflection curves using other modeling methods are less (i.e. “stiffer”) than the load test values. However, if load factors of 2.0 and higher are selected, the computed deflections would be about 2 or 3 mm (0.078 to 0.118 in.) with the experiment showing about 4 mm (0.157 in.). Thus, the differences are probably not very important in the range of the service loading. 10,000 Lateral Load, kN 8,000 Pile B 6,000 4,000 Unmodified EI Analytical ACI Experimental 2,000 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Groundline Deflection, mm Figure 3-61 Comparison of Experimental and Computed Values of Pile-Head Deflection for Different Values of EI, San Francisco Test Also shown in Figure 3-61 is a curve showing deflection as a function of lateral load with no reduction in the values of EI. The need to reduce EI as a function of bending moment is apparent. Values of bending stiffness in Figure 3-62 along with EI of the gross section were used to compute the maximum bending moment mobilized in the shaft as a function of the applied load are shown in Figure 3-63. The close agreement between computations from all the methods is striking. The curve based on the gross value of EI is reasonably close to the curves based on adjusted values of EI, indicating that the computation of bending moment for this particular example is not very sensitive to the selected values of bending stiffness. 142 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Bending Stiffness, kN-m2 106 40 Analytical Experimental ACI 30 20 10 0 5,000 0 10,000 15,000 20,000 Bending Moment, kN-m Figure 3-62 Values of EI for three methods, San Francisco test 10,000 Lateral Load, kN 7,500 5,000 Unmodified EI Analytical ACI Experimental 2,500 0 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 Bending Moment, kN-m Figure 3-63 Comparison of Experimental and Computed Values of Maximum Bending Moments for Different Values of EI, San Francisco Test 143 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-9 p-y Curves for Massive Rock 3-9-1 Introduction Liang, Yang, and Nusairat (2009) developed a criterion for computing p-y curves for drilled shafts in massive rock. This criterion is based on both full-scale load tests and threedimensional finite element modeling. A hyperbolic equation is used as the basis for the p-y relationship p y 1 y K i pu .......................................................(3-124) where pu is the ultimate lateral resistance of the rock mass and Ki is the initial slope of the p-y curve. A drawing of the p-y curve for massive rock is presented in Figure 3-64. Both of these parameters, Ki and pu, are computed using the properties of the rock mass. The ultimate lateral resistance pu is computed for two conditions; near the ground surface and at great depth. The lower of the two values of pu is used in computing the p-y curve. p pu p y 1 y K i pu Ki y Figure 3-64 p-y Curve in Massive Rock 3-9-2 Shearing Properties of Massive Rock The shearing properties, c and , used in computing the p-y curve for massive rock are defined using the Hoek-Brown (1980) strength criterion for rock. In the Hoek-Brown strength criterion, the major and minor principal stresses are related by 144 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock a 1 3 ci mb 3 s ............................................(3-125) ci where 1 and 3 are the major and minor principal stresses at failure, ci is the uniaxial compressive strength of intact rock, and the parameters mb, s, and a are material constants that depend on the characteristics of the rock mass; s = 1 for intact rock, and a = 0.5 for most rock types. The parameters mb and s can be determined for many types of rock using the recommendations of Marinos and Hoek (2000).4 Parameter mb can be computed using the HoekBrown material index mi and the Geologic Strength Index, GSI, and blast damage factor Dr using mb mi e GSI 100 2814Dr ...................................................(3-126) Representative values for the Hoek-Brown material index are presented in Table 3-10. For deep excavations like drilled shaft or bored piles, the blast damage factor Dr is assumed equal to zero. Hoek (1990) provided a method for estimating the Mohr-Coulomb failure parameters c and of the rock mass from the principal stresses at failure. These parameters are: 2 .............................................(3-127) 1 3 90 arcsin c n tan ....................................................(3-128) 1 can be found from Equation 3-125, and n and are found from n 3 1 3 2 2 1 3 0.5mb ci 1 3 1 4 ........................................(3-129) mb ci ...........................................(3-130) 2 1 3 This reference may be obtained from the Internet at https://www.rocscience.com/education/hoeks_corner#. 145 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Table 3-10 Values of Material Index mi for Intact Rock, by Rock Group (from Hoek, 2001) Rock Type Class Group Clastic Carbonates Sedimentary Non-clastic Evaporites Organic Non Foliated Metamorphic Slightly Foliated Foliated** Light Plutonic Dark Igneous Hypabyssal Lava Volcanic Pyroclastic Texture (values in parenthesis are estimates) Coarse Medium Fine Very Fine Conglomerates* Siltstones Claystones (21±3) Sandstones 7±2 4±2 Breccias 14±2 Graywackes Shales (19±5) (18±3) (6±2) Chrystalline Sparitic Micritic Dolomites limestones Limestones Limestones (9±3) (12±3) (10±2) (9±2) Gypsum Anhydrite 8±2 12±2 Chalk 7±2 Hornfels Marble (19±4) Quartzites 9±3 Metasandstone 20±3 (19±3) Migmatite Amphibolites (29±3) 26±6 Gneiss Schists Phyllites Slates 28±5 12±3 (7±3) 7±4 Granite Diorite 32±3 25±5 Granodiorite (29±3) Gabbro 27±3 Dolerite Norite (16±5) 20±5 Porphyries Diabase Peridotite (20±5) (15±5) (25±5) Rhyolite Dacite (25±5) (25±3) Obsidian Andesite Basalt (19±3) 25±5 (25±5) Agglomerate Breccia Tuff (19±3) (19±5) (13±5) * Conglomerates and breccias may present a wide range of mi values depending on the nature of the cementing material and degree of cementation, so they may range from values similar to sandstone to values used for fine-grained sediments. ** These values for intact rock specimens tested normal to bedding or foliation. The values of mi will be significantly different if failure occurs along a weakness plane. 3-9-3 Determination of Rock Mass Modulus Two methods for evaluating the modulus of the rock mass are recommended by Liang et al. One method is to compute rock mass modulus by multiplying the intact rock modulus measured in the laboratory by the modulus reduction ratio Em / Ei , computed from the geological strength index, GSI, using Equation 3-131. E eGSI / 21.7 ............................................(3-131) Em Ei m Ei 100 Ei 146 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock The experimental data and correlation for the modulus reduction ratio are shown as a function of GSI in Figure 3-65. 100 Bieniawski (1978) Serafin and Pereira (1983) Ironton-Russell Regression Line GSI / 21.7 E e % E 100 m Em/Ei, (%) Modulus Reduction Ratio 80 i 60 40 20 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 Geologic Strength Index Figure 3-65 Equation for Estimating Modulus Reduction Ratio from Geological Strength Index The second method recommended by Liang et al. for determining the modulus of the rock mass is to perform an in-situ rock pressuremeter test. The difficulty in using this approach is that many pressuremeter testing devices are not capable of reaching sufficiently large pressures to deform the rock. If this is the case, interpretation of test results may be restricted because of the limited range of expansion pressures achievable. Values for Poisson’s ratio are also required to compute p-y curves in massive rock. Values of Poisson’s ratio vary with the quality of the rock mass. Typical values for Poisson’s ratio and other properties for rock masses reported by Hoek (2001) are shown in Table 3-11. Values of Poisson ratio for the rock mass can be estimated by interpretation measurements of in-situ stress wave velocities. Poisson’s ratio can be computed from the compression and shear wave velocities using Equation 3-132 (Zhang, 2004). This relationship is drawn in Figure 3-66. (V p / Vs ) 2 2 2 [(V p / Vs ) 2 1] 147 ................................................ (3-132) Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Table 3-11 Typical Properties for Rock Masses (from Hoek, 2001) Property Symbol Intact Rock Strength Hoek-Brown Constant Geological Strength Index Friction Angle Cohesive Strength Poisson’s Ratio ci Good Quality Hard Rock Mass 150 MPa 21,750 psi 80 MPa 11,600 psi Very Poor Quality Rock Mass 20 MPa 2,900 psi mi 25 12 8 GSI 75 50 30 46 deg. 33 deg. 24 deg. c 13 MPa 1,885 psi 3.5 MPa 500 psi 0.55 MPa 80 psi 0.2 0.25 0.3 Average Rock Mass 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 0 1 2 3 Vp/Vs 4 5 6 Figure 3-66 Poisson’s Ratio as Function of Stress Wave Velocity Ratio 3-9-4 Determination of pus Near the Ground Surface For a passive wedge type failure near the ground surface, as shown in Figure 3-67, the ultimate lateral resistance per unit length, pus of the drilled shaft at depth H near the ground surface is pus 2C1 cos sin C2 sin 2C4 sin C5 ...........................(3-133) where 45 2 and 2 . 148 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Fs Fs H Fnet W Fa Fn D Figure 3-67 Model of Passive Wedge for Drilled Shafts in Rock Liang, et al. note that the value of 3 can be taken as the effective overburden pressure at a depth of H/3 for estimating and c using Equations 3-127 and 3-128. The following equations are used to compute parameters C1 through C5 with c = effective cohesion, = effective friction angle, and, = effective unit weight respectively of the rock mass. K a tan 2 45 2 K 0 1 sin z0 2c v0 Ka H C1 H tan sec c K 0 v0 tan K 0 tan 2 C2 C3 tan cD sec 2H tan sec tan D tan v0 H H tan 2 tan 2 v0 H cD 2 H tan tan 2C1 cos cos C3 sin tan cos 149 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock H C4 K 0 H tan sec v0 , and 2 C5 K a H z0 D , with the condition that C5 0 Equation 3-133 is valid for homogeneous rock mass. For layered rock mass, representative properties can be computed by a weighted method based on the volume of the failure wedge. Methods for obtaining the rock properties c and are given in Section 3-9-2 on page 156. 3-9-5 Determination of pud at Great Depth The passive wedge failure mechanism is not likely to form if the overburden pressure is sufficiently large. Studies of rock sockets using three-dimensional stress analysis using the finite element method have concluded that at depth the rock failure first in tension, followed by failure in friction between the shaft and rock, followed finally by failure of the rock in compression. Therefore, the expression for ultimate resistance at depth is a function of the limiting pressure, pL, and the peak frictional resistance max. The ultimate resistance at depth can be computed using 2 pud pL max pa D ..........................................(3-134) 3 4 where pa is the active horizontal active earth pressure given by pa Ka v 2c Ka with the condition that pa 0 ........................(3-135) The effective overburden pressure, v, at the depth under consideration includes the pressure from overburden soils. The limiting normal pressure of the rock mass, pL, is taken as the compressive strength of the rock mass, 1, computed using Equation 3-125 and equating 3 equal to v,. a pL v ci mb v s ............................................(3-136) ci The limiting shear stress, max, is the maximum axial side resistance of the rock-shaft interface, proposed by Rowe and Armitage (1987). max 0.45 ci .....................................................(3-137) where both max and ci are in units of megapascals. Values of max in units of kPa and psi are computed by LPile using the following equations: For max and ci in units of kPa: max 14.23025 ci ......................(3-138) 150 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock For max and ci in units of psi: max 5.4194 ci .......................(3-139) 3-9-6 Determination of Initial Tangent Stiffness of p-y Curve Ki The initial tangent stiffness of the p-y curve, Ki, is computed rock mass modulus, Poisson’s ratio, pile diameter, and mobilized bending stiffness of the pile using D Ki Em D ref 2 E p I p e E D 4 m 0.284 ........................................(3-140) where Em is the modulus of the rock mass, is Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass, D is the diameter of the drilled shaft, Dref is a reference shaft diameter equal to 0.3048 m or 12 inches, and E p I p is the bending stiffness of the drilled shaft. 3-9-7 Procedure for Computing p-y Curves in Massive Rock 1. Obtain the values of the intact rock strength ci and the intact rock modulus Ei. 2. Obtain values for the rock mass modulus, Em, by either use of Equation 3-131 if pressuremeter data are unavailable or from interpretation of pressuremeter testing results. If Equation 3-131 is used, obtain values of GSI and mi according to the recommendations of Marinos and Hoek (2000). 3. Obtain the value of Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass from in-situ measurements or estimated from Table 3-11. 4. Select a shaft diameter, compressive strength of concrete, and reinforcing details. 5. Compute the bending stiffness and nominal moment capacity of the drilled shaft. Set the value of bending stiffness equal to the cracked section bending stiffness at a level of loading where the reinforcement is in the elastic range. 6. Compute Ki using Equation 3-140. 7. Compute pus at shallow depth using Equation 3-133 with 3 equal to the vertical effective stress at H/3 when computing the values of and c using Equations 3-127 and 3-128. 8. Compute pud at great depth using Equation 3-134 with pL computed using Equation 3-136 and equating 3 equal to v. 9. Compute pu as the smaller of pus computed using Equation 3-133 or pud computed using Equation 3-134. 10. The values of the p can then be computed as a function of y, Ki, and pu using Equation 3-124 as a function of pile displacement y. 151 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-10 p-y Curves in Piedmont Residual Soils The Piedmont residual soils are found east of the Appalachian ridge in a region extending from southeastern Pennsylvania south through Maryland, central Virginia, eastern North Carolina, eastern South Carolina, northern Georgia, into Alabama. It is a weathered in-place rock, underlain by metamorphic rock. In general, the engineering behavior of Piedmont residual soil is poorly understood, due to difficulties in obtaining undisturbed samples for laboratory testing and relatively wide variability. The degree of weathering varies with local conditions. Weathering is greatest at the ground surface and decreases with depth until the unweathered, parent rock is found. The residual soil profile is often divided into three zones: an upper zone of red, sandy clays, an intermediate zone of micaceous silts, and a weathered zone of gravelly sands mixed with rock. Often the boundaries of the zones are indistinct or inclined. Weathering is greatest near seepage zones. The method for computing p-y curves in Piedmont residual soils was developed by Simpson and Brown (2006). This method was developed to use correlations for estimates of soil modulus measured using four field testing methods: dilatometer, Menard pressuremeter, Standard Penetration Test, and cone penetration tests. The basic method is described in the following paragraphs. Given a shaft diameter b, and soil modulus Es, the relationship between p and y is p Es b y ......................................................(3-141) This relationship is considered to be linear up to y/b = 0.001 (0.1 percent). For y/b values greater than 0.001, y/b for 0.001 y/b 0.0375 ..........................(3-142) Es Esi 1 ln 0.001 pu b y 1 3.624 .................................................(3-143) where = –0.23, which gives pu 1.834Esib y Esi Etest 152 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Es/Esi 1 ln y/b Figure 3-68 Degradation Plot for Es pu y 0.001b 0.0375b Figure 3-69 p-y Curve for Piedmont Residual Soil 3-11 Response of Layered Soils There are conditions where the soil profile near the ground surface is composed of soil layers of different types. If the layers are in the shallow range of depths where the soil would move up and out as a wedge, some modifications are needed to the methods to compute the ultimate soil resistance pu in the formulations for p-y curves for different soil layers. The effect of a layered soil profile on lateral load-transfer behavior was investigated by Allen (1985). However, the methods developed by Allen require the use of several specialpurpose computer programs. Full integration of the methods developed by Allen with the 153 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock methods shown herein must be delayed until a later date when this research can be implemented in a readily usable form. Earlier, a method for making layering corrections was proposed by Georgiadis (1983). This method, while not addressing all possible combinations of commonly encountered conditions, has been implemented as a feature in LPile. The following section describes this method. 3-11-1 Layering Correction Method of Georgiadis The layering correction method proposed by Georgiadis (1983) is based on the determination of “equivalent” depths of all the layers below the upper layer. To do this, the integral of ultimate resistances are computed over the depth of the upper layer using the methods for homogeneous soils. The equivalent depth h2 to the top of the underlying layer is computed by equating the integral of the ultimate resistances over the depth of the overlying layer, F0, to the integral of ultimate resistance of the underlying layer, F1, assuming that the overlying layer is composed of the same material properties as the underlying layer. Thus, the following two integrals are equal and the unknown quantity is the upper limit for the integral, h2 for layer 2. F0 h1 pu1dz ..................................................... (3-144) 0 and F1 h2 pu 2 dz ......................................................(3-145) 0 The equivalent thickness h2 of the upper layer along with the soil properties of the second layer, are then used to compute the p-y curves and integral of pu over the depth of the second layer. The procedure to compute h2 is the following. First, the F0 integral is computed by dividing the upper layer into 100 evenly thick slices and computing the F0 integral using Simpson’s rule. Next, the upper limit of the F1 integral is computed using the trapezoidal integration rule using layers of 0.01 m thickness and the test function equal to F1 minus F0 is computed. The upper limit h2 is determined when the test function equals zero. This final value of h2 is determined by determining the two trial values for h2 when the test function transitions from being negative to positive in sign, then interpolating to determine the value of h2 for which the test function is equal to zero. If there are more layers requiring layering correction, the integrals F0 and F1 are added together to get the new F0 and the equivalent depth of the next underlying layer is computed as described above. Note that the discussion above has assumed that the pile head is located at the ground surface. If the pile head is above the ground surface, the equivalent depths of multiple soil layers will be computed as the same values as if the pile head is located at the ground surface. If the pile head is below the ground surface, the computed values for the equivalent depths will be 154 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock different due to the different profile of vertical effective stress versus depth and due to the F0 integral being computed over a fraction of the depth of the top soil layer between the pile head and the bottom of the layer. The magnitude of the differences between the equivalent depths of the different pile head elevations depend on the data defining the pile and soil layer properties. The concepts presented here can be used to get the equivalent thicknesses of multiple, dissimilar layers of soil overlying the layer for which the equivalent depth is desired. The equivalent depths may be either smaller or greater than the actual depths of the soil layers and will depend on the relative strengths of the layers in the soil profiles. This is illustrated in Figure 3-70. F1 = Total force acting on pile above point i at the point of soil failure hi = Equivalent depth of top of layer i Groundline h3 h1 Soft Soil (Layer 1) h2 1 F1 Stronger Soil Below Weaker Soil (behaves as if shallower) 2 F2 Weaker Soil Below Stronger Soil (behaves as if deeper) F3 Figure 3-70 Illustration of Equivalent Depths in a Multi-layer Soil Profile It should be noted that it is possible that conditions could be present that were not directly addressed by the method of Georgiadis, but must be addressed in the layering correction computations. A few of these conditions are: sloping ground surface, which causes the p-y curves to be stronger for pile displacements in the uphill direction and weaker in the downhill direction battered piles (similar effect to sloping ground surface) tapered piles for which pile diameter varies with depth when the pile head is below the ground surface (how are the limits of the F0 integral determined for top layer?) 155 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock how values of effective stress are computed in the underlying layers (are the values of effective stress equal to the true effective stress or an “equivalent” effective stress based on the equivalent depth?) soil properties that vary with depth (how should any increase in strength with depth in the lower layer be extrapolated upward when matching the F1 integral for the upper layers?) what to do when peak resistance is higher than the residual resistance, as is the case for stiff clay with free water. The basic approach is to follow the general procedure outlined by Georgiadis, with the additional assumptions needed to handle the conditions listed above. The ground surface is always considered as flat and the pile is considered as vertical so the equivalent depths are equal for loading in both the uphill and downhill directions and the outbatter and in-batter directions. To do otherwise would cause abrupt changes in the equivalent layer effects for small changes in ground slope when the ground surface is nearly flat or when the pile is only slightly battered. In the case of tapered piles and variable soil properties, the F1 integral is computed assuming that the pile diameter is equal to the pile diameter at the top of the underlying layer and the shear strength values at the top of the underlying layer are used. Effective stresses in the expressions for pu are computed using the actual depths in all computations. In cases where the residual resistance is lower than the peak resistance, as is the case for stiff clay with free water, the residual resistance is used. The layering correction computations may yield results that are predictable in conditions where pile diameter is constant and soil properties do not vary with depth in a layer and not always predictable in other conditions where pile diameter and soil properties vary significantly with depth. 3-11-2 Example p-y Curves in Layered Soils In this section, an example problem will be presented to illustrate how the layering correction computations are performed. In the first part of this section, the example will present a hand solution and in the second part the results of the computer solution will be presented. The example problem to demonstrate the manner in which layered soils are modeled is shown in Figure 3-71. As seen in the sketch, a pile with a diameter of 610 mm (24 in.) is embedded in soil consisting of an upper layer of soft clay, overlying a layer of loose sand, which in turn overlays a layer of stiff clay. The water table is at the ground surface, and the loading is static. This example was first presented in Single Piles and Pile Groups Under Lateral Loading by Reese and Van Impe, 2011. Four p-y curves are to be computed at depths A, B, C and D, as shown in Figure 3-72. These four depths are at 1, 3, 5, and 9 m below the pile head. The four p-y curves computed for the case of layered soils are shown in Figure 3-73. The curve at a depth of 1 m is in the upper layer of soft clay; the curve at the depth of 3 m is in the sand layer below the soft clay; and the curves for the depth of 5 m and 9 m are in the lower layer of stiff clay without free water. Note 156 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock that the legend shows the depths of the p-y curves below the pile head, not the equivalent depths. The equivalent depths are listed in the output report for the LPile analysis. 0m 2.00 m Soft Clay 2.00 m Loose Sand c = 25 kPa 50 = 0.02 = 8.0 kN/m3 2.00 m = 30 deg. = 8.0 kN/m3 4.00 m c = 100 kPa 50 = 0.005 = 10.0 kN/m3 Stiff Clay without Free Water 6.00 m Static Loading 10.00 m 610 mm Figure 3-71 Soil Profile for Example of Layered Soils 0m Soft Clay A Loose Sand B xEQ = 2.388 m 2.0 m xEQ = 2.036 m 4.0 m C Stiff Clay D Point Actual Depth, m Equivalent Depth, m A 1.0 1.000 B 3.0 3.388 C 5.0 3.036 D 9.0 9.000 10.0 m 610 mm Figure 3-72 Equivalent Depths of Soil Layers Used for Computing p-y Curves 157 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 600 550 Load Intensity p, kN/m 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25 Lateral Deflection y, m Depth = 1.00 m Depth = 3.00 m Depth = 5.00 m Depth = 9.00 m Figure 3-73 Example p-y Curves for Layered Soil 3-11-2-1 Hand Computation Example Following the method suggested by Georgiadis, the p-y curve for soft clay can be computed as if the profile consists only of that soil. The value of pu was computed to be 63.1 kN/m and the p-y curve was computed using Equations 3-20 and 3-21, shown below. avg J pu 3 x x cb .............................................. (3-20) c b pu 9 c b .......................................................... (3-21) When dealing with the layer of loose sand, an equivalent depth is found such that the integrals of the ultimate soil resistance of an equivalent sand layer and for the soft clay are equal at the interface. The first step is to employ Equations 3-20 and 3-21 of Section 3-3-7 for pu for the soft clay and to compute the sum of pu values at the depth of 2 m. Preliminary computations showed that the transition depth xr where Equations 3-20 and 3-21 are equal occurred at a depth of 5.56 m, therefore Equation 3-20 would be used over the full depth of 2 m. The value of pu 158 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock varies linearly with depth and values of 45.7 kN/m and 80.5 kN/m were computed for depths of 0 and 2 m, respectively. The sum of values of pu was computed to be 126.2 kN at a depth of 2 m. The next step is compute the depth of the sand with the properties shown in Figure 3-71 such that the integral of the computed values of pu for the sand will equal 126.2 kN. The equations for pu in sand are nonlinear and the integration must be performed numerically. Equation 3-53 and Equation 3-54 are employed, along with values of As , to compute values of pu values as a function of depth. Figure 3-28 was employed and values of As are tabulated for ease of computation in Table 3-12 below. Preliminary computations find that the intersection of Equations 3-53 and 3-54 occurs at 8.3 m below the ground surface so Equation 3-53 is used for all computations of pu. Tabulated values of pu and the F1 integral in sand are shown in Table 313 for each 0.5 m of depth. Interpolating between the values in Table 3-13 found that the F1 integral equaled the value of F0 at a depth of 2.35 m. Thus, the equivalent thickness of loose sand to replace the 2.0 m of soft clay was found to be 2.35 meters. Thus, the equivalent depth to point B in loose sand, 1m below the top of layer 2, is 3.35 meters. K x tan sin tan pst x 0 (b x tan tan ) .................... (3-53) tan( ) cos tan( ) K 0 x tan (tan sin tan ) K Ab psd K A b x(tan8 1) K0 b x tan tan4 ............................. (3-54) Table 3-12 Tablulated Values of As as Function of z/b z/b As 0 2.88 0.5 2.497 1.0 2.113 1.5 1.73 2.0 1.47 2.5 1.24 3.0 1.05 3.5 0.95 4.0 0.90 4.5 0.88 below 4.5 0.88 159 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Table 3-13 Computed Values of pu and F1 for the Sand in Figure 3-71 as Function of Depth Depth, m pu, kN/m F1, kN 0 0 0 0.5 23.26 5.812 1.0 47.33 23.46 1.5 67.95 52.28 2.0 87.20 91.07 2.5 115.31 141.70 3.0 155.48 209.40 3.5 204.95 299.50 4.0 261.14 416.03 4.5 324.07 562.33 An equivalent depth of stiff clay was found such that the sum of the ultimate soil resistance for the top of the stiff clay layer is equal to the sum of the ultimate soil resistance of the loose sand and soft clay. In making the computations, the equivalent and actual thicknesses of the loose sand, 2.35 m and 2.00 m, were replaced by 2.10 m of stiff clay. Thus, the actual thicknesses of the soft clay and loose sand of 4.00 m were reduced by 1.90 m, leading to equivalent depths in the stiff clay of point C of 3.10 m. Point D fell at a depth for which deep conditions control, so the equivalent and actual depths were equivalent and equal to 9.00 m. 3-11-2-2 Computer Solution Example The same problem was analyzed by LPile and the results computed for the equivalent depths of the tops of layers are presented in Tables 3-14. The equivalent depths for the p-y curves computed by hand and by LPile are presented in Table 3-15. The results are approximately equivalent and the numerical differences are due to the thinner layers used in the computer solution. The computed p-y curves are illustrated in Figure 3-72. Table 3-14 Equivalent Depths of Tops of Soil Layers Computed by LPile Layer No. Top of Layer Below Pile Head, meters 1 2 3 0.00 2.0000 4.0000 Equivalent Top Depth Same Layer Layer is Below Pile Type As Rock or is Head, Layer Above Below Rock meters 0.00 N.A. No 2.3883 No No 2.0053 No No *F0 for layer n+1 = F0 + F1 for layer n. 160 F0 Integral for Layer, kN* F1 Integral for Layer, kN 0.00 126.2600 477.3266 126.2600 351.0666 N.A. Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock 3-11-2-3 Comment on Choice of Layer Type for Stiff Clay Another point of interest is that the recommendations for p-y curves for stiff clay in the presence of no free water were used for the stiff clay. This decision was based on the assumption that the sand above the stiff clay can move downward and fill any gap that might develop between the clay and the pile. Furthermore, in the pile load test in stiff clay with free water, the free water was flushed out of the annual space between the soil and pile with each cycle of loading, thereby eroding soil from around the upper portion of the pile. The presence of soft clay and sand to a depth of 4.00 m above the stiff clay is believed to adequate to suppress the erosion of soil by the free water even if the sand does not fill in any potential gap around the pile. Table 3-15 Equivalent Depths of Example p-y Curves Computed by Hand and by LPile Equivalent Depth of p-y Curve by Hand, m Equivalent Depth of p-y Curve by LPile, m p-y Curve Layer Depth of p-y Curve, m A soft clay 1 1.00 1.0000 B sand 3 3.35 3.3883 C stiff clay 5 3.10 3.0053 D stiff clay 9 9.00 9.0000 3-11-3 Modified Equations Using Equivalent Depth The equations used to compute lateral load transfer at failure are the ultimate values for flat ground surfaces and vertical piles. Layering corrections are applied only to the p-y curve models that have different expressions for ultimate lateral load transfer for shallow and deep conditions. The six p-y curve models that have different expressions for shallow and deep conditions are: soft clay by Matlock, API soft clay, Stiff clay with free water, Stiff clay without free water, Stiff clay without free water with user-defined k value, and Cemented c- soil (cemented silt) The following notation is used in the modified equations. Note that “elevation” is the depth below the pile head. The equivalent depth is defined as a distance below the pile head and that the equivalent depth may be either shallower or deeper than the actual depth below the pile head. xeq = equivalent depth 161 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock xeq = equivalent depth of top of soil layer + elevation of nodal point – Elevation of Layer Top xact = Actual depth below ground surface 3-11-3-1 Soft Clays Under Static Loading Conditions x J pu 3 avg act xeq cb .......................................... (3-146) c b pu 9 c b ........................................................ (3-147) 3-11-3-2 Soft Clay Under Cyclic Loading Conditions xr 6cb ..................................................... (3-148) b Jc x p 0.72 pu eq .................................................. (3-149) xr 3-11-3-3 Stiff Clay with Free Water Under Static Loading conditions pct 2cavgb bxact 2.83cavg xeq ..................................... (3-150) pcd 11c b ...................................................... (3-151) pc min pct , pcd ..................................................(3-152) p pc 1.225 As 0.75 As 0.411 .................................... (3-153) Where As is determined from the ratio xeq/b 3-11-3-4 Stiff Clay with Free Water Under Cyclic Loading Conditions p 0.936 Ac pc 0.102 pc y p ........................................ (3-154) y 50 Where Ac is determined from the ratio xeq/b Stiff clay without free water for both static and cyclic loading: 162 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock J pus 3 avg xact xeq cb ......................................... (3-155) c b pud 9 c b ........................................................ (3-156) pu min pus , pud ................................................. (3-157) 3-11-3-5 Sand K x tan( ) sin( ) tan( ) pst xact 0 b xeq tan( ) tan( ) ............ (3-158) tan( ) cos( ) tan( ) K 0 xeq tan( ) tan( ) sin( ) tan( ) K Ab psd K A b xact tan8 ( ) 1 K0 b xact tan( ) tan4 ( ) ..................... (3-159) ps min pst , psd ................................................. (3-160) pu As ps or pu Ac ps ............................................ (3-161) 3-11-3-6 API Sand pus (C1 xeq C2b) xact ............................................. (3-162) pud C3b xact .................................................... (3-163) pu min pus , pud ................................................. (3-164) where: 1 C1 tan( ) K p tan( ) K 0 tan( ) sin( ) 1 tan( ) .......... (3-165) cos( ) C2 K p K a .................................................... (3-166) C3 K p2 K p K0 tan( ) Ka ........................................ (3-167) 3-11-3-7 Cemented c- Soils K x tan( ) sin( ) tan( ) ps xact 0 eq b xeq tan( ) tan( ) ....................... (3-168) tan( ) cos( ) tan( ) K 0 xeq tan( )tan( ) sin( ) tan( ) K Ab 163 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock pd K A b xact tan8 ( ) 1 K0 b x tan tan4 ( ) ................................................ (3-169) pu min ps , pd ................................................. (3-170) Compute pu for static loading using pu As pu ...................................................... (3-171) or for cyclic loading using pu Ac pu ...................................................... (3-172) Use the appropriate value of As or Ac from Figure 3-28 for the particular non-dimensional depth (xeq/b) and type of loading. p A pu ......................................................... (3-173) 3-12 Modifications to p-y Curves for Pile Batter and Ground Slope 3-12-1 Piles in Sloping Ground The formulations for p-y curves presented to this manual were developed for a horizontal ground surface. In order to allow designs to be made if a pile is installed on a slope, modifications must be made to the p-y curves. The modifications involve revisions in the manner in which the ultimate soil resistance is computed. In this regard, the assumption is made that the flow-around failure that occurs at depth will not be influenced by sloping ground; therefore, only the equations for the wedge-type failures near the ground surface need modification. The modifications to p-y curves presented here are based on earth pressure theory and should be considered as preliminary. Future changes may be needed once laboratory and field study are completed. 3-12-1-1 Equations for Ultimate Resistance in Clay in Sloping Ground The ultimate soil resistance at the ground surface for a pile in in saturated clay with a horizontal ground surface was developed by Reese (1958) and is ( pu ) ca 2 ca b b H 2.83 ca H ..................................... (3-174) If the ground surface has a slope angle as shown in Figure 3-74, the soil resistance in the downhill direction of movement, following Reese’s approach is: ( pu ) ca 2 ca b b H 2.83 ca H The soil resistance in the uphill direction of movement is: 164 1 ............................. (3-175) 1 tan Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock ( pu ) ca 2 ca b b H 2.83 ca H cos ....................... (3-176) 2 cos(45 ) + + Figure 3-74 Pile in Sloping Ground and Battered Pile where: (pu)ca = ultimate soil resistance near ground surface, ca = average undrained shear strength, b = pile diameter, = average unit weight of soil, H = depth from ground surface to point along pile where soil resistance is computed, and = angle of slope as measured in degrees from the horizontal. A comparison of Equations 3-175 and 3-176 shows that the equations are identical except for the terms at the right side of the parenthesis. If is equal to zero, the equations become equal to the original equation. 3-12-1-2 Equations for Ultimate Resistance in Sand The ultimate soil resistance at the ground surface for a pile in in sand with a horizontal ground surface is 165 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock K H tan sin tan ( pu ) sa H 0 (b H tan tan ) ............... (3-177) tan( ) cos tan( ) K 0 H tan (tan sin tan ) K Ab If the ground surface has a slope angle , the ultimate soil resistance in the downhill direction is: K H tan sin ( pu ) sa H 0 ( 4 D13 3D12 1) tan( ) cos tan bD2 H tan tan D22 tan( ) ............... (3-178) K 0 H tan (tan sin tan )( 4 D13 3D12 1) K Ab where: D1 tan tan ................................................. (3-179) tan tan 1 D2 1 D1 , and ................................................... (3-180) K A cos cos cos 2 cos 2 cos cos 2 cos 2 .................................... (3-181) where is defined in Figure 3-74. Note that the denominator of Equation 3-179 for D1 will equal zero when the sum of the slope and friction angles is 90 degrees. This occurs when the inclination of the failure wedge is parallel to the ground surface. In computations, the lower value of (pu)sa or to pu from Equation 3-54 is used, so no computational problem arises. The ultimate soil resistance in the uphill direction is: K H tan sin ( pu ) sa H 0 ( 4 D33 3D32 1) tan( ) cos tan bD4 H tan tan D42 tan( ) ............... (3-182) K 0 H tan (tan sin tan )( 4 D33 3D32 1) K Ab where D3 tan tan ................................................ (3-183) 1 tan tan 166 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock and D4 D3 1 ....................................................... (3-184) This completes the necessary derivations for modifying the equations for clay and sand to analyze a pile under lateral load in sloping ground. 3-12-1-3 Effect of Direction of Loading on Output p-y Curves The equations for computing maximum soil resistance for p-y curves in sand depend on whether the pile is being pushed up or down the slope. LPile determines which case to compute by using the values of lateral pile deflection and slope angle. Whenever, p-y curves are generated for output, the curve that is output by the program is based on the lateral deflection computed for loading case 1. If the user desires output of both sides of an unsymmetrical p-y curve it is necessary to run an analysis twice, with the pile-head loadings for shear, moment, rotation, or displacement reversed for the two analyses, while keeping the axial thrust force unchanged. The user may then combine the two output curves together. 3-12-2 Effect of Batter on p-y Curves in Clay and Sand Piles are sometimes constructed with an intentional inclination. This inclination or angle is called batter and piles that are not vertical are called battered piles. Vertical piles are sometimes referred to as “plumb” piles. The effect of batter on the behavior of laterally loaded piles has been investigated in several model test studies. The lateral, soil-resistance curves for a vertical pile in a horizontal ground surface were modified by a modifying constant to account for the effect of the inclination of the pile. The values of the modifying constant as a function of the batter angle were deduced from the results of the model tests (Awoshika and Reese, 1971) and from results of full-scale tests reported by Kubo (1964). The modifying constant to be used is shown by the solid line in Figure 3-75. 167 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock Pile Batter Angle in LPile, degrees Ratio of Soil Resistance 2.0 30 20 0 10 10 20 − 30 Load 1.0 Kubo’s tests Awoshika’s tests 0 30 20 10 0 10 20 30 Ground Slope Angle in LPile, degrees Figure 3-75 Soil Resistance Ratios for p-y Curves for Battered Piles from Experiment from Kubo (1964) and Awoshika and Reese (1971) This modifying constant is used to increase or decrease the value of pult, which will in turn cause the p-values to be modified proportionally. While it is likely that the values of pult for the deeper soils are not affected by pile batter, the behavior of a pile is only slightly affected by the resistance of the deeper soils; therefore, the use of the modifying constant for all depths of a battered pile is believed to be satisfactory. As shown in Figure 3-75, the agreement between the empirical curve and the experiments for the outward batter piles ( is positive) agrees somewhat better that for the inward batter piles. The data indicate that the use of the modifying constant for inward batter piles will yield results that are somewhat doubtful; therefore, on important projects, full-scale load testing is desirable. 3-12-3 Modeling of Piles in Short Slopes Whenever piles are installed in slopes, the user has two methods available in LPile to model the pile and slope. One way is the specify the slope angle of the ground surface and the other way is to use Figure 3-75 to determine what value of p-multiplier to use. The best choice of which method to use depends on the elevation of the pile tip. If the pile tip is above the toe of the slope, the user should just specify the ground slope angle and pile batter angle. LPile will then compute the effective slope angle, e, as the difference between the pile batter angle and the ground slope angle i. LPile then uses e in place of 168 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock If the pile tip is below the toe of the slope, the user should specify a p-multiplier over the depth range that is above the toe of the slope. For example, if the slope ratio is 3 to 1 and the pile is loaded in the downslope direction, the p-multiplier is approximately 0.5. 3-13 Shearing Force Acting at Pile Tip It is possible to include a shearing force at the bottom of the pile in the development of the finite difference equations. Inclusion of the modelling of a shearing force at the pile tip would be become important only to those cases where the pile is short; that is, where there is only one point of zero deflection in the pile. Currently, formulations to compute a curve of shearing force as a function of deflection are unavailable. It is believed that construction techniques will have a major effect on the development of shearing forces at the pile tip. It is not possible for design engineers to know what these effects are since design computations are usually performed far in advance of construction of the foundations. At present, all that the geotechnical engineer can do is to make an estimate of the necessary force-deflection curve by considering pile geometry and soil properties or to infer a relationship from the results of load tests on piles of similar size at the site of the project. 169 Chapter 3 – Lateral Load-Transfer Curves for Soil and Rock (This page was deliberately left blank) 170 Chapter 4 Special Analyses 4-1 Introduction LPile has several options for making special analyses. This chapter provides explanations about the various options and guidance for using the optional features for making special analyses. 4-2 Computation of Top Deflection versus Pile Length This option is available only in the conventional analysis mode and is not available in the LRFD analysis mode. The activation of this option is made by selecting the option when entering the load definitions. Note that this option is not available if one of the pile head loading conditions is displacement. In the following example, shown in Figure 4-1, a pile with elastic bending properties is loaded with five levels of pile-head shear at 0%, 50%, 100%, 150%, and 200% of the service load. The following figures illustrate the problem conditions, lateral pile deflection versus depth, pile-top deflection versus displacement, and curves of pile-top deflection versus pile length. When the problem computes the curves of pile-top deflection versus pile length, the program first computes pile-top deflection for the full length. The full pile length is 12 meters in this example. Then LPile reduces the pile length in increments of 5 percent of the full length (0.6 meters in this example). Thus, the pile length values for which pile-top deflection is computed for are 12 meters, 11.4 meters, 10.8 meters, and so on, until the computed pile-top deflection becomes excessive. A typical plot top deflection versus pile length for a pile in soil profile composed of layers of clay and sand is shown in Figure 4-4. Usually, when LPile generates this graph, it uses all of the computed values. However, in cases where there is a change in sign of lateral deflection when the pile is shortened, LPile will omit all data points with an opposite sign from the top deflection for the full length. When examining the results in a graph of top deflection versus pile length, the design engineer may find that the top deflection at full length is too large and that some change in the dimensions of the pile are required. The manner in which this decision is made depends on the shape of the curves in the graph. If the right-hand portions of the curves are flat or nearly flat, it is not possible to reduce pile-top deflection by lengthening the pile. The only available option is to increase the diameter of the pile or to increase the number of piles, so that the average load per pile is reduced. 171 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses 250 kN DL + 100 kN LL = 350 kN Service Loads Shown 80 kN DL + 20 kN LL = 100 kN Soft Clay, 6 m Sand, 9 m M=0 c = 12 to 24 kPa = 8.95 kN/m3 = 38 to 40 = 9.50 kN/m3 Elastic Circular Pile with L = 12 m, D = 1 m, E = 27,500,000 kPa Figure 4-1 Pile and Soil Profile for Example Problem Figure 4-2 Variation of Top Deflection versus Depth for Example Problem 172 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses 200 Shear Force, kN 150 100 50 0 0 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.01 0.012 0.014 0.016 0.018 0.02 0.022 0.024 Top Deflection, m Figure 4-3 Pile-head Load versus Deflection for Example Figure 4-4 Top Deflection versus Pile Length for Example If the right-hand portions of the curves are inclined, it is possible to reduce the pile-top deflection by lengthening the pile. However, there are situations where other factors may need to be considered. One common situation is when the pile-top deflection is acceptable as long as the 173 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses pile tip is sufficiently embedded in a strong layer of soil or rock. In this case, the designer must decide how reliably the depth of the strong layer can be predicted. In such a case, the designer may wish to specify the depth of a drilled foundation long enough to penetrate into the strong layer and add a requirement for the construction inspector to notify the design engineer if the strong layer is not reached after drilling to the planned depth. In the case of a driven pile foundation, the design engineer can set the pile length to be long enough to reach a specified driving resistance that is based a pile driving analysis that is based on the presence of the strong layer. 4-3 Analysis of Piles Loaded by Soil Movements In general, a pile subjected to lateral loading is supported by the soil. However, there are cases in which the soil is displaced and the load imparted by the displaced soil must be taken into account. Lateral soil movements can result from several causes. A few of the causes are slope movements (probably the most common cause), nearby fill placement or excavation, and lateral soil movements due to seepage forces resulting from water flowing through the soil in which the pile is founded. A number of cases involved with pile loaded by soil movements have been reported in the literature. In many cases, the piles have supported bridge abutments for which the bridge approach embankments were unstable. Earthquakes are another source of lateral soil movements. Free-field displacements are motions of the soil that may be induced by the earthquake, or by unstable slope movements or lateral spreading triggered by the earthquake. This important problem can be extremely complex to analyze. In such a case, the first step in the solution is to predict the soil movements with depth below the soil surface using special analyses that may consider a synthetic acceleration time history of the design earthquake. Isenhower (1992) developed a method of analysis based on computing soil reaction as a function of the relative displacement between the pile and soil. If the pile at a particular depth undergoes greater displacement than the soil movement at that depth then the soil will provide resistance to the pile. If the opposite occurs, the soil will then apply an extra lateral loading to the pile. If a pile is in a soil layer undergoing lateral movement, the soil reaction depends on the relative movement of the pile and soil. The p-y modulus is evaluated for a pile displacement relative to the soil displacement. This technique is illustrated in Figure 4-5. The solution is implemented in LPile by modifying the governing differential equation to EI d4y d2y Q E py ( y ys ) W 0 .......................................(4-1) dx 4 dx 2 It should be noted that it is often difficult to determine the soil displacement profile for use in the LPile analysis. Occasionally, it is possible to install slope inclinometer casings at a project site to measure soil displacements as they develop. In other cases, the soil displacement profile may be developed using the finite element method. 174 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses p ps y yys ys Epy y Figure 4-5 Evaluation of Soil Modulus from p-y Curve Displaced by Soil Movement Analyses that include loading by soil movements is controlled by two options in the Program Options and Settings dialog. These options are to input a single soil movement profile that is applied to all cases of loading or to input multiple profiles of soil movement versus depth that are applied to specified load cases. The user should note that loading by soil movement profiles is available only for conventional analysis and is not available for LRFD analyses. 4-4 Analysis of Pile Buckling It is possible to use LPile to analyze pile buckling using an iterative procedure, combined with evaluation of the computed results by the user. The following describes a typical procedure and a potential difficulty caused by inappropriate input. 4-4-1 Procedure for Analysis of Pile Buckling The procedure for analysis of pile buckling is the following. 1. In the Program Options and Settings, increase the maximum number iterations to 975 to avoid early termination of an analysis 2. Make an initial conventional analysis in which the maximum loads expected for the foundation are analyzed. Note the sign of the pile-head deflection, which will depend on the sign of the applied loads. If the pile section is nonlinear (not elastic, elastic-plastic, or user-input nonlinear bending), examine the output report to find the maximum axial structural capacity for the pile. Use this axial structural capacity to estimate the maximum axial thrust load to be applied in the buckling analysis. 175 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses 3. In the Program Options and Settings dialog, select a pile buckling analysis by checking the Computational Options group. 4. Open the Controls for Pile Buckling Analysis dialog 5. Select the appropriate pile-head fixity condition for the pile buckling analysis. 6. Enter the maximum pile-head loading for the pile-head fixity condition. 7. Increase the magnitude of axial thrust force in even increments for the subsequent load cases. An initial increment size may be 5 percent of the axial structural capacity. Up to 100 load steps may be specified. 8. Perform the analysis with the option for pile buckling analysis. 9. Examine the output report and pile buckling graph. An example of a buckling study was performed. The pile head is at the ground surface. The soil profile is composed of three layers and is sand from 0 to 2 meters (API sand, = 18 kN/m3, = 30 degrees, and k = 13,550 kN/m3), soft clay from 2 to 8.5 meters ( = 7.19 kN/m3, c = 1 kPa, 50 = 0.06), and sand below 8.5 meters (API sand, = 10 kN/m3, = 40 degrees, k = 60,000 kN/m3). The pile has a diameter of 0.15 meters, a length of 18 meters, a cross-sectional area of 0.0177 m2, a moment of inertia of 1.678 10-7, and a Young’s modulus of 200 GPa. Two pile buckling curves are plotted in Figure 3-6. For one curve, the specified lateral shear force is 0.1 kN and buckling failure occurs for thrust values above 218 kN. For the second curve, the specified lateral shear force is 1.0 kN and buckling failure occurs for thrust values above 121 kN. This graph illustrates that the buckling capacity is a function of the pile head loading conditions, with the lower pile buckling capacity associated with the higher loading condition. These curves illustrate that the axial buckling capacity is a function of the specified lateral shear force used in the analysis and that the buckling capacity is reduced as the lateral shear force is increased. Thus, it is important to use the maximum expected load condition, if it is known, since a range of computed buckling capacities is possible. 176 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses 250 V = 0.1 kN Axial Thrust Force, kN 200 V = 1.0 kN 150 100 50 0 0 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.01 Pilehead Deflection, meters Figure 4-6 Examples of Pile Buckling Curves for Different Shear Force Values 4-4-2 Example of An Incorrect Pile Buckling Analysis The following is an example of an incorrect buckling analysis. In this analysis, the soil and pile properties are the same as used in the example above. The shear force is specified as 5.0 kN (larger than the 0.1 and 1.0 kN thrust values used in the prior example). If the section is either a drilled shaft (bored pile) or prestressed concrete pile with low levels of reinforcement, it may be possible to obtain buckling results for axial thrust values higher than the axial buckling capacity, but the sign will be reversed. The reason for this is a large axial thrust value will create compression over the full section. This causes the moment capacity to be controlled by crushing of the concrete and not by yielding of the reinforcement. In the incorrect analysis shown in Figure 3-7, the incorrect analysis used a range of axial thrust forces that was too large and the computed lateral deflections were on both positive and negative as shown in Figure 3-7. In a correct buckling analysis, the computed lateral deflections should always have the same sign. In the correct analysis, also shown in Figure 3-7, the axial thrust values were increased in smaller increments and non-convergence due to excessive lateral deflections occurred at a thrust levels higher than 39 kN. 177 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses 450 Correct 400 Incorrect Axial Thrust Force, kN 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0 0.1 0.2 Pile-head Deflection, meters Figure 4-7 Examples of Correct and Incorrect Pile Buckling Analyses 4-4-3 Evaluation of Pile Buckling Capacity The analysis of buckling cannot calculate the buckling capacity theoretically. It can only evaluated the buckling capacity approximately by simulating the pre-buckling behavior. The results of an analysis can be interpreted using a technique based on the fitting of a hyperbolic curve to the computed results for pre-buckling behavior. A typical buckling-deformation curve for a given set of pile-head loading is shown in Figure 4-8. The lateral deflection of the pile head is denoted by y0. The equation for a hyperbolic curve that originates at y0 is P y y0 .......................................................(4-2) b a y y 0 Where y is deflection, P is the axial thrust force and a and b are curve-fitting parameters. This expression may be re-written as y y0 b a y y 0 ...................................................(4-3) P 178 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses The pile deflections may be re-plotted in which values of y y 0 are plotted along the xaxis and values of y y 0 / P are plotted along the y-axis. In many cases, this will result in a straight line with a slope of a and a y-intercept of b as shown in Figure 4-9. P y0 Pile-head Deflection, y Figure 4-8 Typical Results from Pile Buckling Analysis y y0 P a 1 b y – y0 Figure 4-9 Pile Buckling Results Showing a and b The pile buckling capacity, Pcrit, is calculated from 179 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses Pcrit 1 ...............................................................(4-4) a The estimate pile buckling capacity is computed from the shape of the pile-head response curve and is not based on the magnitude of maximum moment compared to the plastic moment capacity of the pile. For piles with nonlinear bending behavior, the estimated buckling capacity may over-estimate the actual buckling capacity if the buckling capacity is controlled by the pile’s plastic moment capacity. Thus, for analyses of nonlinear piles, the user should compare the maximum moment developed in the pile to the plastic moment capacity. If the two values are close, the buckling capacity should be reported as the last axial thrust value for which a solution was reported. 4-5 Pushover Analysis of Piles The program feature for pushover analysis has options for different pile-head fixity options and the setting of the range and distribution of pushover deflection. The output of the pushover analysis is displayed in graphs of pile-head shear force versus deflection and maximum moment developed in the pile versus deflection. The dialog for input of controls for performing a pushover analysis are shown in Figure 4-10. The control parameters allow the user to specify the pile-head fixity condition and how the pushover displacement points are generated. Optionally, the user may specify the pushover displacements to be used. Figure 4-10 LPile Dialog for Controls for Pushover Analysis 180 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses 4-5-1 Procedure for Pushover Analysis The pushover analysis is performed by running a series of analyses for displacement-zero moment pile-head conditions for pinned-head piles and analyses for displacement-zero slope pile-head conditions for fixed head piles. The displacements used are controlled by the maximum and minimum displacement values specified and the displacement distribution method. The displacement distribution method may be either logarithmic (which requires a non-zero, positive minimum and maximum displacement values), arithmetic, or a set of user-specified pile-head displacement values. The number of loading steps sets the number of pile-head displacement values generated for the pushover analysis. The axial thrust force used in the pushover analysis must be entered in the dialog. If the pile being analyzed is not an elastic pile, the user should make sure that the axial thrust force entered matches one the values for axial thrust entered in the conventional pile-head loadings table to make sure that the correct nonlinear bending properties are used in the pushover analysis. If the values do not match, the nonlinear bending properties for the next closest axial thrust will be used by LPile for the pushover analysis. 4-5-2 Example of Pushover Analysis Some typical results from a pushover analysis are presented in the following two figures. Figure 4-11 presents the pile-head shear force versus displacement for pinned and fixed-head conditions and indicates the maximum level of shear force that can be developed for the two conditions. Similarly, Figure 4-12 presents the maximum moment developed in the pile (a prestressed concrete pile in this example) versus displacement and shows that a plastic hinge develops in the fixed-head pile at a lower displacement than for the pinned-head pile. Formation of plastic hinge Figure 4-11 Pile-head Shear Force versus Displacement from Pushover Analysis 181 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses Formation of plastic hinge Figure 4-12 Maximum Moment Developed in Pile versus Displacement from Pushover Analysis In general, it is not possible to develop more than one plastic hinge in a pile if the pilehead condition is pinned. It is sometimes possible to develop two plastic hinges in the pile if the pile-head condition is fixed against rotation and the axial load is zero. 4-5-3 Evaluation of Pushover Analysis Evaluation of a pushover analysis requires examination of both graphs generated by the analysis. It is important to identify the load levels at which plastic hinges form and the location of the plastic hinges. In many practical situations, the pile-head fixity conditions are neither fixed or free, but may be close to one of these conditions. If actual conditions are close to being fixed-head conditions, the amount of pile-head deflection required to develop a plastic hinge will be somewhat greater than the value shown in the pushover analysis for fixed-head conditions. Similarly, if actual conditions are close to being free-head, the amount of pile-head deflection required to develop a plastic hinge will be somewhat less than the value shown in the pushover analysis for free-head conditions. 4-6 Computation of Foundation Stiffness Matrix Stiffness matrices are often used to model foundations in structural analyses and LPile provides an option for evaluating the lateral stiffness of a deep foundation. This feature of LPile allows the user to solve for stiffness coefficients, as illustrated by the sketches shown in Figure 4-13, of pile-head movements and rotations as functions of incremental loadings. The stiffness coefficients are computed by dividing the applied pile-head loadings into increments and then computing the pile head reactions for each level of loading. First, the deflection of the pile head is computed for each lateral-load increment with the rotation at the pile head being restrained to zero. Next, the rotation of the pile head is computed for each bending-moment increment with the lateral deflection at the pile head being restrained to zero. The user can thus define the 182 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses stiffness matrix directly based on the relationship between computed deformation and applied load. For instance, the stiffness coefficient K33, shown in Figure 4-13, can be obtained by dividing the applied moment M by the computed rotation θ at the pile head. K33 K22 Moment M K11 K33 Rotation K11 0 0 K11 x P 0 0 0 0 Q x 0 K K23 y V 22 K K H y 0 22 K 32 23K33 M K 32 K 33 M Figure 4-13 Example of Stiffness Matrix of Foundation The definitions of the pile-head stiffness values and their engineering units computed by LPile are the following: pile - head shear force reaction lbs kN or pile - head deflection inch meter pile - head moment reaction in - lbs kN - m K 32 or pile - head deflection inch meter pile - head shear force reaction lbs kN K 23 or pile - head rotation radian radian pile - head moment reaction in - lbs kN - m K 33 or pile - head rotation radian radian K 22 The nature of the cross-coupled stiffness coefficients is illustrated in Figure 4-14. 183 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses M y=0 0 V K 22 V y K 23 V K 32 M y K 33 M M y0 V Coupled shear restores zero deflection =0 Coupled moment restores zero rotation Figure 4-14 Coefficients of Pile-head Stiffness Matrix Most analytical methods in structural mechanics can employ either the stiffness matrix or the flexibility matrix to define the support condition at the pile head. If the user prefers to use the stiffness matrix in the structural model, Figure 4-14 illustrates the procedures used to compute a stiffness matrix. The initial coefficients for the stiffness matrix may be defined based on the magnitude of the service load. The user may need to make several iterations before achieving acceptable agreement. The dialog for Controls for Computation of Stiffness Matrix is shown in Figure 4-15. The feature for computation of pile-head stiffness matrix values has three options to control how the values are computed. In the first method, which is identical to the method used in versions of LPile prior to LPile 2013, the loads used for computation of pile-head stiffness are those specified in Load Case 1 for conventional loading. This method did not allow the user to control the lateral displacement and pile-head rotation, so the second and third options were added to provide this capability. In the second method, the maximum displacement and rotation are set by the values computed for Load Case 1 for conventional loading. In the third method, the user may specify the maximum values of pile-head displacement and rotation. 184 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses Figure 4-15 Dialog for Controls for Computation of Stiffness Matrix In all three methods, the user may control the number of steps of loading and the method used to compute the steps of loading. Up to 100 step of loading can be specified, with the default value equal to 10 steps. The computation method used to compute the magnitudes of the steps of loading may either be scaled in proportion of the logarithm of the specified loading or by evenly spaced values (arithmetically distributed values). 185 Chapter 4 – Special Analyses (This page was deliberately left blank) 186 Chapter 5 Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity 5-1 Introduction 5-1-1 Application The designer of deep foundations under lateral loading must make computations to ascertain that three factors of performance are within tolerable limits: combined axial and bending stress, shear stress, and pile-head deflection. The flexural rigidity, EI, of the deep foundation (bending stiffness) is an important parameter that influences the computations (Reese and Wang, 1988; Isenhower, 1994). In general, flexural rigidity of reinforced concrete varies nonlinearly with the level of applied bending moment, and to employ a constant value of EI in the p-y analysis for a concrete pile will result in some degree of inaccuracy in the computations. The response of a pile is nonlinear with respect to load because the soil has nonlinear stress-strain characteristics. Consequently, the load and resistance factor design (LRFD) method is recommended when evaluating piles as structural members. This requires evaluation of the nominal (i.e. unfactored) bending moment of the deep foundation. Special features in LPile have been developed to compute the nominal-moment capacity of a reinforced-concrete drilled shaft, prestressed concrete pile, or steel-pipe pile and to compute the bending stiffness of such piles as a function of applied moment or bending curvature. The designer can utilize this information to make a correct judgment in the selection of a representative EI value in accordance with the loading range and can compute the ultimate lateral load for a given cross-section. 5-1-2 Assumptions The program computes the behavior of a beam or beam-column. It is of interest to note that the EI of the concrete member will undergo a significant change in EI when tensile cracking occurs. In the coding used herein, the assumption is made that the tensile strength of concrete is minimal and that cracking will be closely spaced when it appears. Actually, such cracks will initially be spaced at some distance apart and the change in the EI will not be so drastic. In respect to the cracking of concrete, therefore, the EI for a beam will change more gradually than is given by the coding. The nominal bending moment of a reinforced-concrete section in compression is computed at a compression-control strain limit in concrete of 0.003 and is not affected by the crack spacing. The ultimate bending moment for steel, because of the large amount of deformation of steel when stressed about the proportional limit, is taken at a maximum strain of 0.015, which is five times the crushing strain of concrete. 187 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity For reinforced-concrete sections in tension, the nominal moment capacity of a section is computed at a compression-control strain limit of 0.003 or a maximum tension in the steel reinforcement of 0.005. 5-1-3 Stress-Strain Curves for Concrete and Steel Any number of models can be used for the stress-strain curves for concrete and steel. For the purposes of the computations presented herein, some relatively simple curves are used. The stress-strain curve for concrete is shown in Figure 5-1. f c 0.15 fc Ec 0 0.0038 fr Figure 5-1 Stress-Strain Relationship for Concrete Used by LPile The following equations are used to compute concrete stress. The value of concrete compressive strength, fc, in these equations is specified by the engineer. 2 f c f c 2 for 0 0 .......................................(5-1) 0 0 0 for 0 0.0038 ............................(5-2) f c f c 0.15 f c 0.0038 0 The modulus of rupture, fr, is the tensile strength of concrete in bending. The modulus of rupture for drilled shafts and bored piles is computed using f r 7.5 f c psi in USCS units f r 19.7 f c kPa in SI units .............................................(5-3) The modulus of rupture for prestressed concrete piles is computed using 188 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity f r 4.0 f c psi in USCS units f r 10.5 f c kPa in SI units .............................................(5-4) The modulus of elasticity of concrete, Ec, is computed using Ec 57,000 f c psi in USCS units Ec 151,000 f c kPa in SI units ..........................................(5-5) The compressive strain at peak compressive stress, 0, is computed using 0 1.7 f c ............................................................(5-6) Ec The tensile strain at fracture for concrete, t, is computed using t 0 1 1 fr f c ...................................................(5-7) The stress-strain (-) curve for steel is shown in Figure 5-2. There is no practical limit to plastic deformation in tension or compression. The stress-strain curves for tension and compression are assumed identical in shape. fy y Figure 5-2 Stress-Strain Relationship for Reinforcing Steel Used by LPile 189 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity The yield strength of the steel, fy, is selected according to the material being used, and the following equations apply. y fy Es ...............................................................(5-8) where Es = 200,000 MPa (29,000,000 psi). The models and the equations shown here are employed in the derivations that are shown subsequently. 5-1-4 Cross Sectional Shape Types The following types of cross sections can be analyzed: 1. Square or rectangular, reinforced concrete, 2. Circular, reinforced concrete, 3. Circular, reinforced concrete, with permanent steel casing, 4. Circular, reinforced concrete, with permanent steel casing and tubular core, 5. Circular, steel pipe, 6. Round prestressed concrete 7. Round prestressed concrete with hollow circular core, 8. Square prestressed concrete, 9. Square prestressed concrete with hollow circular core, 10. Octagonal prestressed concrete, 11. Octagonal prestressed concrete with hollow circular core, 12. Elastic shapes with rectangular, round, tubular, strong H-sections, or weak H-sections, and 13. Elastic-plastic shapes with rectangular, round, tubular, strong H-sections, or weak Hsections. The computed output consists of a set of values for bending moment M versus bending stiffness EI for different axial loads ranging from zero to the axial-load capacity for the column. 5-2 Beam Theory 5-2-1 Flexural Behavior The flexural behavior of a structural element such as a beam, column, or a pile subjected to bending is dependent upon its flexural rigidity, EI, where E is the modulus of elasticity of the material of which it is made and I is the moment of inertia of the cross section about the axis of bending. In some instances, the values of E and I remain constant for all ranges of stresses to which the member is subjected, but there are situations where both E and I vary with changes in stress conditions because the materials are nonlinear or crack. 190 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity The variation in bending stiffness is significant in reinforced concrete members because concrete is weak in tension and cracks and because of the nonlinearity in stress-strain relationships. As a result, the value of E varies; and because the concrete in the tensile zone below the neutral axis becomes ineffective due to cracking, the value of I is also reduced. When a member is made up of a composite cross section, there is no way to calculate directly the value of E for the member as a whole. The following is a description of the theory used to evaluate the nonlinear momentcurvature relationships in LPile. Consider an element from a beam with an initial unloaded shape of abcd as shown by the dashed lines in Figure 5-3. This beam is subjected to pure bending and the element changes in shape as shown by the solid lines. The relative rotation of the sides of the element is given by the small angle d and the radius of curvature of the elastic element is signified by the length measured from the center of curvature to the neutral axis of the beam. The bending strain x in the beam is given by x dx ...............................................................(5-9) where: = deformation at any distance from the neutral axis, and dx = length of the element along the neutral axis. d a M d b dx M c Figure 5-3 Element of Beam Subjected to Pure Bending The following equality is derived from the geometry of similar triangles 191 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity dx .............................................................(5-10) where: = distance from the neutral axis, and = radius of curvature. Equation 5-11 is obtained from Equations 5-9 and 5-10, as follows: x dx dx 1 .................................................(5-11) dx From Hooke’s Law x E x ...........................................................(5-12) where: x = unit stress along the length of the beam, and E = Young’s modulus. Substituting Equation 5-11 into Equation 5-12, we obtain x E ............................................................(5-13) From beam theory x M ...........................................................(5-14) I where: M = applied moment, and I = moment of inertia of the section. Equating the right sides of Equations 5-13 and 5-14, we obtain M E ..........................................................(5-15) I Cancelling and rearranging Equation 5-15 M 1 .............................................................(5-16) EI 192 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Continuing with the derivation, it can be seen that dx = d and 1 d .........................................................(5-17) dx For convenience here, the symbol is substituted for the curvature 1/. The following equation is developed from this substitution and Equations 5-16 and 5-17 EI M ............................................................(5-18) and because = d and x = /dx, we may express the bending strain as x = .............................................................(5-19) The computation for a reinforced-concrete section, or a section consisting partly or entirely of a pile, proceeds by selecting a value of and estimating the position of the neutral axis. The strain at points along the depth of the beam can be computed by use of Equation 5-19, which in turn will lead to the forces in the concrete and steel. In this step, the assumption is made that the stress-strain curves for concrete and steel are those shown in Section 5-1-3. With the magnitude of the forces, both tension and compression, the equilibrium of the section can be checked, taking into account the external compressive loading. If the section is not in equilibrium, a revised position of the neutral axis is selected and iterations proceed until the neutral axis is found. Bending moment in the section is computed by integrating the moments of forces in the slices times the distances of the slices from the centroid. The value of EI is computed using Equation 5-18. The maximum compressive strain in the section is computed and saved. The computations are repeated by incrementing the value of curvature until a failure strain in the concrete or steel pipe, is developed. The nominal (unfactored) moment capacity of the section is found by interpolation using the values of maximum compressive strain. 5-2-2 Axial Structural Capacity The axial structural capacity, or squash load capacity, is the load at which a short column would fail. Usually, this capacity is so large that it exceeds the axial bearing capacity of the soil, except in the case of rock that is stronger than concrete. Several design equations are used to compute the axial structural capacity, depending on the type of section being analyzed. For reinforced concrete sections (not including prestressed concrete piles) the nominal (unfactored) axial structural capacity, Pn, is Pn 0.85 f c( Ag As ) As f y ............................................(5-20) where Ag is the gross cross-sectional area of the section, As is the cross-sectional area of the longitudinal steel, fc is the specified compressive strength of concrete and fy is the specified yield strength of the longitudinal reinforcing steel. 193 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Common design practice in North America and Europe is to restrict the steel reinforcement to be between 1 and 8 percent of the gross cross-sectional area for drilled shafts without permanent casing. Usually, reinforcement percentages higher than 3.5 to 4 percent are attainable only by a combination of bundling of bars and by reducing the maximum aggregate size to be small enough to pass through the reinforcement cage. LPile has features that help the user to identify the combinations of reinforcement details that satisfy requirement for constructability. For prestressed concrete piles, the equations for the nominal axial structural capacity differ depending on the cross-sectional shape and the level of prestressing. As for uncased reinforced concrete sections, the concrete stress at failure is assumed to be 0.85 fc. With axial loading, the effective prestress in the section is lowered. At a compressive strain of 0.003, only about 60 percent of the prestressing remains in the member. Thus, the nominal strength can be computed as Pn 0.85 f c 0.60 f ps Ag ...............................................(5-21) where fpc is the effective prestress. The service load capacity for short column piles established by the Portland Cement Association is based on a factor of safety between 2 and 3 is N 0.33 f c 0.27 f pc Ag ...............................................(5-22) Conventional construction practice in North American is to use effective prestressing of 600 to 1,200 psi (4.15 to 8.3 MPa) for driven piling. The level of prestressed used varies with the overall length of the pile and local practice. Usually, the designing engineer obtains the value of prestress and fraction of losses from the pile supplier. 5-3 Validation of Method 5-3-1 Analysis of Concrete Sections An example concrete section is shown in Figure 5-4. This rectangular beam-column has a cross section of 510 mm in width and 760 mm in depth and is subjected to both bending moment and axial compression. The compressive axial load is 900 kN. For this example, the compressive strength of the concrete fc is 27,600 kPa, E of the steel is 200 MPa, and the ultimate strength fy of the steel is 413,000 kPa. The section has ten No. 25M bars, each with a cross-sectional area of 0.0005 m2, and the row positions are shown in the Figure 5-4. The following pages show how the values of M and EI as a function of curvature are computed. The results from the solution of the problem by LPile are shown in Table 5-1. The first block of lines include an echo-print of the input, plus several quantities computed from the input data, including the computed squash load capacity (9,093.096 kN), which is the load at which a short column would fail. The next portion of the output presents results of computations for various values of curvature, starting with a value of 0.0000492 rad/m and increasing by even 194 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity increments.5 The fifth column of the output shows the value of the position of the neutral axis, as measured from the compression side of the member. Other columns in the output, for each value of , give the bending moment, the EI, and the maximum compressive strain in the concrete. For the validation that follows, only one line of output was selected. 0.510 m 0.076 m 0.203 m 0.203 m 0.760 m 0.203 m 0.076 m No. 25M bars Figure 5-4 Validation Problem for Mechanistic Analysis of Rectangular Section 5-3-1-1 Computations Using Equations of Section 5-2 An examination of the output in Table 5-1 finds that the maximum compressive strain was 0.0030056 for a value of of 0.0176673 rad/m. This maximum strain is close to 0.003, the value selected for computation of the nominal bending moment capacity, and that line of output was selected for the basis of the following hand computations. 5-3-1-2 Check of Position of the Neutral Axis In Table 5-1, the neutral axis is 0.1701205 m from the top of the section. The computer found this value by iteration by balancing the computed axial thrust force against the specified axial thrust. For the hand computations, the computed axial thrust for this neutral axis position will be checked against the specified axial thrust. In the hand computations, the value of the depth to the neutral axis was rounded to 0.1701 m for convenience. 5 LPile uses an algorithm to compute the initial increment of curvature that is based on the depth of the pile section. This algorithm is designed to obtain initial values of curvature small enough to capture the uncracked behavior for all pile sizes. 195 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Table 5-1 LPile Output for Rectangular Concrete Section -------------------------------------------------------------------------------Computations of Nominal Moment Capacity and Nonlinear Bending Stiffness -------------------------------------------------------------------------------Axial thrust values were determined from pile-head loading conditions Number of Sections = 1 Section No. 1: Dimensions and Properties of Rectangular Concrete Pile: Length of Section Depth of Section Width of Section Number of Reinforcing Bars Yield Stress of Reinforcing Bars Modulus of Elasticity of Reinforcing Bars Compressive Strength of Concrete Modulus of Rupture of Concrete Gross Area of Pile Total Area of Reinforcing Steel Area Ratio of Steel Reinforcement Nom. Axial Structural Capacity = 0.85 Fc Ac + Fs As = = = = = = = = = = = = 15.24000000 0.76000000 0.51000000 10 413686. 199948000. 27600. -39.40177573 0.38760000 0.00500000 1.28998971 9093.096 m m m bars kPa kPa kPa kPa sq. m sq. m percent kN Reinforcing Bar Details: Bar Number ---------1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bar Index -----------16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 Bar Diam. m -----------0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 0.025200 Bar Area sq. m -----------0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 0.000500 Bar X m ------------0.167500 0.000000 0.167500 -0.167500 0.167500 -0.167500 0.167500 -0.167500 0.000000 0.167500 Bar Y m -----------0.304800 0.304800 0.304800 0.101600 0.101600 -0.101600 -0.101600 -0.304800 -0.304800 -0.304800 Concrete Properties: Compressive Strength of Concrete Modulus of Elasticity of Concrete Modulus of Rupture of Concrete Compression Strain at Peak Stress Tensile Strain at Fracture Maximum Coarse Aggregate Size = = = = = = 27600. 24865024. -3271.7136591 0.0018870 -0.0001154 0.0190500 kPa kPa kPa m Number of Axial Thrust Force Values Determined from Pile-head Loadings = 1 Number -----1 Axial Thrust Force kN -----------------900.000 Definitions of Run Messages and Notes: C = concrete has cracked in tension Y = stress in reinforcement has reached yield stress T = tensile strain in reinforcement exceeds 0.005 when compressive strain in concrete is less than 0.003. Bending stiffness = bending moment / curvature Position of neutral axis is measured from compression side of pile Compressive stresses are positive in sign. Tensile stresses are negative in sign. Axial Thrust Force = 900.000 kN Bending Bending Bending Depth to Max Comp Max Tens Max Concrete Max Steel Curvature Moment Stiffness N Axis Strain Strain Stress Stress rad/m kN-m kN-m2 m m/m m/m kPa kPa ------------- ------------- ------------- ------------- ------------- ------------- ------------- ------------0.0000492 28.3173948 575409. 1.9085538 0.0000939 0.0000565 2674.0029283 18743. 0.0000984 56.6333321 575395. 1.1451716 0.0001127 0.0000379 3188.4483827 22462. . . (deleted lines) 196 Run Msg --- Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity . 0.0004429 0.0004921 0.0005413 0.0005906 253.1619332 280.6180646 280.6180646 280.6180646 . . (deleted lines) . 0.0038878 651.6508321 0.0039862 663.0531399 0.0040846 674.4235902 0.0041831 685.7618089 . . (deleted lines) . 0.0176673 907.1915259 . . (deleted lines) . 0.0239665 913.9027316 571583. 570216. 518378. 475180. 0.5542915 0.5375669 0.4727569 0.4548249 0.0002455 0.0002646 0.0002559 0.0002686 -0.0000911 -0.0001095 -0.0001555 -0.0001802 6671.6631466 7149.3433542 6926.7437852 7241.7196541 48751. 52522. 50760. 53257. 167614. 166336. 165112. 163937. 0.2450564 0.2440064 0.2430210 0.2420960 0.0009527 0.0009727 0.0009927 0.0010127 -0.0020020 -0.0020569 -0.0021117 -0.0021664 20619. 20904. 21183. 21458. -397341. -408237. -413686. -413686. C C CY CY 51349. 0.1701205 0.0030056 -0.0104216 27596. 413686. CY 38132. 0.1658249 0.0039742 -0.0142403 27600. 413686. CY C C -------------------------------------------------------------------------------Summary of Results for Nominal (Unfactored) Moment Capacity for Section 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------Moment values interpolated at maximum compressive strain = 0.003 or maximum developed moment if pile fails at smaller strains. Load No. ---1 Axial Thrust kN ---------------900.000 Nominal Mom. Cap. kN-m -----------------907.021 Max. Comp. Strain -----------0.00300000 Note that the values of moment capacity in the table above are not factored by a strength reduction factor (phi-factor). In ACI 318-08, the value of the strength reduction factor depends on whether the transverse reinforcing steel bars are spirals or tied hoops. The above values should be multiplied by the appropriate strength reduction factor to compute ultimate moment capacity according to ACI 318-08, Section 9.3.2.2 or the value required by the design standard being followed. 5-3-1-3 Forces in Reinforcing Steel The rows of steel in Figure 5-4 are numbered from the top downward. Therefore, Row 1 will be in compression and the other rows will be in tension. The strain in each row of bars is computed using Equation 5-19, as follows (with the positive sign indicating compression). 1 = = (0.0176673 rad/m) (0.1701 m 0.0755 m) = +0.001672 Similarly, 2 = 0.001915 3 = 0.005501 4 = 0.009088 In order to obtain the forces in the steel at each level, it is necessary to know if the steel is in the elastic or plastic range. Thus, it is required to compute the value of yield strain y using Equation 5-8. y fy Es 413,000 0.002065 ..........................................(5-23) 2 108 197 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity This computation shows that the bars in rows 1 and 2 are in the elastic range and the bars in the other two rows are in the plastic range. Thus, the forces in each row of bars are: F1 = (3 bars) (5 104 m2/bar) (0. 001447) (2 108 kPa) = 501.51 kN F2 = (2 bars) (5 104 m2/bar) (0. 002779) (2108 kPa) = 382.95 kN F3 = (2 bars) (5 104 m2/bar) (0.007005) (413,000 kPa) = 413.00 kN 4 F4 = (3 bars) (5 10 m /bar) (0.007005) (413,000 kPa) = 619.50 kN Total of forces in the reinforcing bars = 913.95 kN. 2 5-3-1-4 Forces in Concrete In computing the internal force in the concrete, 10 slices that are 17.01 mm (0.670 in.) in thickness are selected for computation of the 0.1701 m of the section in compression. The slices are numbered from the top downward for convenience. The strain is computed at the mid-height of each slice by making use of Equation 5-19. 1 = = (0.0176673 rad/m) (0.1701 m 0.01701 m/2) = 0.00285529 The second value in the parentheses is the distance from the neutral axis to the mid-height of the first slice. Similarly, the strains at the centers of the other slices are: 2 = 0.002554 3 = 0.002254 4 = 0.001954 5 = 0.001653 6 = 0.001353 7 = 0.001052 8 = 0.000751 9 = 0.000451 10 = 0.000150 The forces in the concrete are computed by employing Figure 5-4 and Equations 5-1 through 5-8. The first step is to compute the value of 0 from Equation 5-6 and to see the strains are lower or greater than the strain for the peak stress. 27,600 0.001870 151 , 000 27 , 600 0 1.7 The strain in the top two slices show that stress can be found by use of the second branch of the compressive portion of the curve in Figure 5-1 and the stress in the other slices can be computed using Equation 5-1. From Figure 5-4, the following quantity is computed 0.15 f c 4,140 kPa 198 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Then, the following equation can be used to compute the stress along the descending section of the stress-strain curve corresponding to 1 and 2. 0.001870 f c 27,600 4,140 0.0038 0.001870 From the above equation: fc1 = 25,487 kPa fc2 = 26,132 kPa fc3 = 26,777 kPa fc4 = 27,421 kPa The strains in the other slices are less than 0 so the stresses in the concrete are on the ascending section of the stress-strain curve. The stresses in these slices can be computed by Equation 5-1. 2 f c 3 27,6002 0.001870 0.001870 The other values of fc are computed as follows: fc5 = 27,227 kPa fc6 = 25,484 kPa fc7 = 22,315 kPa fc8 = 17,721 kPa fc9 = 11,702 kPa fc10 = 4,257 kPa The forces in each slice of the concrete due to the compressive stresses are computed by multiplying the area of the slice by the computed stress. All of the slices have the area of 0.00740 m2 (0.0145 m 0.51 m). Thus, the computed forces in the slices are: Fc1 = 221.13 kN Fc2 = 226.72 kN Fc3 = 232.32 kN Fc4 = 237.91 kN Fc5 = 236.23 kN Fc6 = 221.10 kN Fc7 = 193.61 kN Fc8 = 153.75 kN 199 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Fc9 = 101.53 kN Fc10 = 36.93 kN There is a small section of concrete in tension. The depth of the tensile section is determined by the strains up to the strain developed at the modulus of rupture (Equation 5-3). f r 19.7 27,600 3,273 kPa In this zone, it is assumed that the stress-stain curve in tension is defined by the average concrete modulus (Equation 5-5). The modulus of elasticity of concrete, Ec, is computed using Ec 151,000 27,600 25,086,000 kPa The strain at rupture is then r 3,273 0.0001305 25,086,000 The thickness of the tension zone is computed using Equation 5-19 as h r 0.0001305 0.07384 m 0.0176673 The force in tension is the product of average tensile stress is and the area in tension and is E Ft r c 0.073840.510 6.16 kN 2 A reduction in the computed concrete force is needed because the top row of steel bars is in compression zone. The compressive force computed in concrete for the area occupied by the steel bars must be subtracted from the computed value. The compressive strain at the location of the top row of bars is 0.001447, the area of the bars is 0.0015 m2, the concrete stress is 27,289 kPa, and the force is 40.93 kN. Thus, the total force carried in the concrete is sum of the computed compressive forces plus the tensile concrete force minus the correction for the area of concrete occupied by the top row of reinforce is 1814.10 kN. 5-3-1-5 Computation of Balance of Axial Thrust Forces The summation of the internal forces yields the following expression for the sum of axial thrust forces: 200 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity F = 1814.10 kN 913.95 kN = 900.15 kN. Taking into account the applied axial load in compression of 900 kN, the section is out of balance by only 0.15 kN (33.7 lbs). This hand computation confirms the validity of the computations made by LPile. The selection of a thickness of the increments of concrete of 0.01701 m is thicker than that used in LPile. LPile uses 100 slices of the full section depth in its computations, so the slice thickness used by LPile is 0.0076 m for this example problem. In addition, some error was introduced by the reduced precision used in the hand computations, whereas LPile uses 64-bit precision in all computations. 5-3-1-6 Computation of Bending Moment and EI Bending moment is computed by summing the products of the slice forces about the centroid of the section. The axial thrust load does not cause a moment because it is applied with no eccentricity. The moments in the steel bars and concrete can be added together because the bending strains are compatible in the two materials. The moments due to forces in the steel bars are computed by multiplying the forces in the steel bars times the distances from the centroid of the section. The values of moment in the steel bars are: Moment due to bar row 1: (479.1 kN) (0.3045) = 152.71 kN-m Moment due to bar row 2: (411.9 kN) (0.1015) = 38.87 kN-m Moment due to bar row 3: (415.0 kN) ( 0.1015) = 41.92 kN-m Moment due to bar row 4: (622.5 kN) ( 0.3045) = 188.64 kN-m Total moment due to stresses in steel bars = 344.40 kN-m The moments due to forces in the concrete are computed by multiplying the forces in the concrete times the distances from the centroid of the section. The values of moments in the concrete slices are: Moment in slice 1: (241.37 kN) (0.3728 m) = 82.15 kN-m Moment in slice 2: (248.29 kN) (0.3583 m) = 80.37 kN-m Moment in slice 3: (255.21 kN) (0.3438 m) = 78.40 kN-m Moment in slice 4: (257.61 kN) (0.3293 m) = 76.24 kN-m Moment in slice 5: (247.22 kN) (0.3148 m) = 71.68 kN-m Moment in slice 6: (226.19 kN) (0.3003 m) = 63.33 kN-m Moment in slice 7: (194.53 kN) (0.2858 m) = 52.16 kN-m Moment in slice 8: ( 152.24 kN) (0.2713 m) = 38.81 kN-m Moment in slice 9: ( 99.32 kN) (0.2568 m) = 23.90 kN-m Moment in slice 10: ( 35.76 kN) (0.2423 m) = 8.07 kN-m Moment correction for top row of bars = (40.93 kN) (0.3045 m) = 201 12.46 kN-m Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Total moment due to stresses in concrete = 561.32 kN-m Sum of moments in steel bars and concrete = 905.71 kN-m As mentioned above, the summation of the moments in the steel bars and concrete is possible because the bending strains in the two materials are compatible, i.e. the bending strains are consistent with the positions of the steel bars and concrete slices. 5-3-1-7 Computation of Bending Stiffness Using Approximate Method The drawing in Figure 5-5 shows the information used in computing the nominal moment capacity. The forces in the steel were computed by multiplying the stress developed in the steel by the area, for either of two or three bars in a row at each row position. 0.1701 m 0.076 m 501.51 kN 0.203 m 382.95 kN 0.203 m 0.760 m 413 kN 0.203 m 619.5 kN 0.076 m Figure 5-5 Free Body Diagram Used for Computing Nominal Moment Capacity of Reinforced Concrete Section The value of bending stiffness is computed using Equation 5-18. EI M 905.71 kN - m 51.265.02 kN - m 2 0.01701205 rad/m A comparison of results from hand versus computer solutions is summarized in Table 52. The moment computed by LPile was 907.19 kN-m. Thus, the hand calculation is within 0.16% of the computer solution. The value of the EI is computed by LPile is 51,348.62 kN-m2. The hand solution is within 0.16% of the computer solution. The hand solution for axial thrust is within 0.0167% of the computer solution The agreement is close between the values computed by hand using only a small number of slices and the values from the computer solution computed using 100 slices. This example hand computation serves to confirm of the accuracy of the computer solution for the problem that was examined. 202 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Table 5-2 Comparison of Results from Hand Computation versus Computer Solution Parameter By LPile By Hand Hand Error, % Moment Capacity, kN-m 907.19 905.71 0.16% Bending Stiffness, EI, kN-m2 51,348.62 51,265.02 0.16% Axial Thrust, kN 900.00* 900.15 +0.0167% * Input value The rectangular section used for above example solution was chosen because the geometric shapes of the slices are easy to visualize and their areas and centroid positions are easy to compute. In reality, the algorithms used in LPile for the geometrical computation are much more powerful because of the circular and non-circular shapes considered in the computations. For example, when a large number of slices are used in computations, individual bars are divided by the slice boundaries. So, in the computations made by LPile, the areas and positions of centroids in each circular segment of the bars are computed. In addition, the areas of bars and strands in a slice are subtracted from the area of concrete in a slice. The two following graphs are examples of the output from LPile for curves of moment versus curvature and ending stiffness versus bending moment. These graphs are examples of the output from the presentation graphics utility that is part of LPile. Both of these graphs were exported as enhanced Windows metafiles, which were then pasted into this document. Moment vs. Curvature - All Sections 1,000 950 900 850 800 750 700 Moment, kN-m 650 600 550 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 0.0 0.005 0.01 0.015 Curvature, radians/m Figure 5-6 Bending Moment versus Curvature 203 0.02 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity 600,000 550,000 500,000 450,000 400,000 EI, kN-m² 350,000 300,000 250,000 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 Bending Moment, kN-m Figure 5-7 Bending Moment versus Bending Stiffness 9,000 8,500 8,000 7,500 7,000 6,500 6,000 5,500 5,000 4,500 4,000 3,500 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 0 200 400 600 800 1,000 1,200 Unfactored Bending Moment, kN-m Figure 5-8 Interaction Diagram for Nominal Moment Capacity 204 900 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity 5-3-2 Analysis of Steel Pipe Piles The method of Section 5-3-1 can be used to make a computation of the plastic moment capacity Mp of steel pipe piles to compare with the value computed using LPile. The pipe section that was selected is shown in Figure 5-9. The pipe section has an outer diameter of 838 mm and an inner diameter of 781.7 mm. The value of the nominal moment was selected as 7,488 kN-m from Figure 5-10 at a maximum curvature of 0.015 radians/meter. 414,000 kPa 0.838 m 0.7817 m Figure 5-9 Example Pipe Section for Computation of Plastic Moment Capacity 8,000 7,500 7,000 6,500 6,000 5,500 Moment, kN-m 5,000 4,500 4,000 3,500 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 0.0 0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009 0.01 0.011 0.012 0.013 0.014 0.015 Curvature, radians/m Figure 5-10 Moment versus Curvature of Example Pipe Section In the computations shown below, the assumption was made that the strain was sufficient to develop the ultimate strength of the steel, 4.14 105 kPa, over the entire section. From the 205 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity practical point of view, it is unrealistic to assume that the bending strains developed in a section can be large enough to yield the condition that is assumed; however, the computation should result in a value that is larger than 7,488 kN-m (5,863 ft-kips) but in the appropriate range. The expression for the plastic moment capacity Mp is the product of the yield stress fy and plastic modulus Z. M p f y Z ..........................................................(5-24) Referring to the dimensions shown in Figure 5-9, the plastic modulus Z of the pipe is Z d 3 o di3 1.847 10 2 m3 6 The computed moment capacity is M p 4.14 105 kPa 1.847 m3 7,647 kN - m As expected, the value of Mp computed from the plastic modulus is slightly larger than the 7,488 kN-m from the computed solution at a strain of 0.0149 rad/m. However, the close agreement and the slight over-estimation provide confidence that the computer code computes the plastic moment capacity accurately. Another check on the accuracy of the computations is to examine the computed bending stiffness in the elastic range. From elastic theory, the bending stiffness for the example problem is EI E d o4 d i4 64 2 10 kPa 8 0.838 m 4 0.7817 m 4 64 1,175,726 kN - m 2 The value computed by LPile is 1,175,686 kN-m2. The error in bending stiffness for the computed solution is 0.0035 percent, which is amazingly accurate for a numerical computation. Please note that the fifth through seventh digits in the above values are shown to be able to illustrate the comparison and are not indicative of the precision possible in normal computations. Often, engineers use specified material strengths that are usually exceeded in reality. The reason that the bending stiffness value computed by LPile is slightly smaller than the full plastic yield value is that the stresses and strains near the neutral axis remain in the elastic range. The stress distribution for a curvature of 0.015 rad/m is shown in Figure 5-11. Approximately, the middle third of this section is in the elastic range. 206 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity 414,000 kPa 0.838 m 0.138 m 0.7817 m = 0.015 rad/m Figure 5-11 Elasto-plastic Stress Distribution Computed by LPile 5-3-3 Analysis of Prestressed-Concrete Piles Prestressed-concrete piles are widely used in construction where conditions are suitable for pile driving. A prestressed-concrete pile has a configuration similar to a conventional reinforced-concrete pile except that the longitudinal reinforcing steel is replaced by prestressing steel. The prestressing steel is usually in the form of strands of high-strength wire that are placed inside of cage of spiral steel to provide lateral reinforcement. As the term implies, prestressing creates an initial compressive stress in the pile so the piles have higher capacity in bending and greater tolerance of tension stresses developed during pile driving. Prestressed piles can usually be made lighter and longer than reinforced-concrete piles of the same size. An advantage of prestressed-concrete piles, compared to conventional reinforcedconcrete piles, is durability. Because the concrete is under continuous compression, hairline cracks are kept tightly closed, making prestressed piles more resistant to weathering and corrosion than conventionally reinforced piles. This characteristic of prestressed concrete removes the need for special steel coatings because corrosion is not as serious a problem as for reinforced concrete. Another advantage of prestressing is that application of a bending moment results in a reduction of compressive stresses on the tension side of the pile rather than resulting in cracking as with conventional reinforced concrete members. Thus, there can be an increase in bending stiffness of the prestressed pile as compared to a conventionally reinforced pile of equal size. The use of prestressing leads to a reduction in the ability of the pile to sustain pure compression, a factor that is usually of minor importance in service but must be considered in pile driving analyses. One significant importance is that a considerable bending moment may be applied to a reinforced pile before first cracking. Consequently, the pile-head deflection of the prestressed pile in the uncracked state is substantially reduced, and its performance under service loads is improved. When analyzing a foundation consisting of prestressed piles, the designer must input a value of the level of stress due to prestressing, Fps, after losses due to creep and other factors. The value usually ranges from 600 to 1,200 psi (4,140 to 8,280 kPa), but accurate values can only be found from the manufacturer of the piles. The value of prestress will vary by 207 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity manufacturer from region to region and will also vary with the shape, size, and compressive of the concrete. For most commercially obtained prestressed piles, Fps can be estimated by assuming some level of initial prestressing in the concrete. Given a value of Fps the program solves the statically indeterminate problem of balancing the prestressing forces in the concrete and reinforcement using the nonlinear stress-strain relationships selected for both concrete and reinforcing steel. The stress-strain relationships used in prestressed concrete is defined using the stressstrain curves of concrete recommended by the Design Handbook of the Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI), as shown in Figure 5-12 and in equation form in Equations 5-25 to 5-28. 270 270 ksi 250 250 ksi Minimum yield strength = 243 ksi at 1% Elongation for 270 ksi (ASTM A 416) Stress, ksi 230 Minimum yield strength = 225 ksi at 1% Elongation for 250 ksi (ASTM A 416) 210 190 170 150 0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 Strain, in/in Figure 5-12 Stress-Strain Curves of Prestressing Strands Recommended by PCI Design Handbook, 5th Edition. For 250 ksi 7-wire low-relaxation strands: ps 0.0076 : f ps 28,500 ps (ksi) .......................................(5-25) ps 0.0076; f ps 250 208 0.04 (ksi) ................................(5-26) ps 0.0064 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity For 270 ksi 7-wire low-relaxation strands: ps 0.0086 : f ps 28,500 ps (ksi) .......................................(5-27) ps 0.0086 : f ps 270 0.04 (ksi) .................................(5-28) ps 0.007 PCI does not have any recommendations for grade 300 strands, which are not widely available. The above equations were used as a model to develop a stress-strain relationship for grade 300 strands. The equations are: ps 0.0088846 : f ps 28,500 ps (ksi) ...................................(5-29) ps 0.0088846 : f ps 300 0.0835 (ksi) .............................(5-30) ps 0.0071 For prestressing bars, an elastic-plastic stress-strain curve is used. As noted earlier, the value of the concrete stress due to prestressing is found prior to performance of the moment-curvature analysis. When prestressed concrete piles are analyzed, the initial strains in the concrete and steel due to prestressing must be computed prior to computation of bending stiffness. The corresponding level of prestressing force applied to the reinforcement, Fps is computed by balancing the force carried in the concrete with the force carried in the reinforcement. Thus, Fps c Ac ...........................................................(5-31) where c is the prestress in the concrete and Ac is the cross-sectional area of the concrete. The user should check the output report from the program to see if the computed level of prestressed force in the concrete at the initial stage is in the desired range. The computation procedures for stresses of concrete for a specific curvature of the cross section are the same as that for ordinary concrete, described in a previous section, except the current state of stresses of concrete and strands should take into account the initial stress conditions. The stress levels for both concrete and strands under loading conditions should be checked to ensure that the stresses are in the desired range. Elementary considerations show that a distance from the end of a pile is necessary for the full transfer of stresses from reinforcing steel to concrete. The development length of the strand is not computed in LPile. Usually the zone of development is about 50 the axial strand diameter from the end of the pile. Typical cross sections of prestressed piles are square solid, square hollow, octagonal solid, octagonal hollow, round solid, or round hollow, are shown in Figure 5-13. 209 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Figure 5-13 Sections for Prestressed Concrete Piles Modeled in LPile 5-4 Discussion Use of the mechanistic method of analysis of moment-curvature relations by hand is relatively straightforward for cases of simple cross sections. Use of this method becomes significantly more laborious when using geometrical values for complex cross sections and nonlinear stress-strain relationships of concrete and steel or when including the effect of prestressing in the case of prestressed concrete piles. Thus, use of a computer program is a necessary feature of the method of analysis presented here. A new user to the program may wish to practice using LPile by repeating the solutions for the example problems. When LPile is employed for any problem being addressed by the user, some procedure should be employed to obtain an approximate solution of the section properties in order to verify the results and to detect gross input errors. 210 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity 5-5 Reference Information 5-5-1 Standard Concrete Reinforcing Steel Sizes Name US Std. #3 US Std. #4 US Std. #5 US Std. #6 US Std. #7 US Std. #8 US Std. #9 US Std. #10 US Std. #11 US Std. #14 US Std. #18 ASTM 10M ASTM 15M ASTM 20M ASTM 25M ASTM 30M ASTM 35M ASTM 45M ASTM 55M CEB 6 mm CEB 8 mm CEB 10 mm CEB 12 mm CEB 14 mm CEB 16 mm CEB 20 mm CEB 25 mm CEB 32 mm CEB 40 mm JD6 JD8 JD10 JD13 JD16 JD19 JD22 JD25 JD29 JD32 JD35 JD38 JD41 LPile Index No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 D, in Area, in 0.375 0.500 0.625 0.750 0.875 1.000 1.128 1.270 1.410 1.693 2.257 0.445 0.630 0.768 0.992 1.177 1.406 1.720 2.220 0.236 0.315 0.394 0.472 0.551 0.630 0.787 0.984 1.260 1.575 0.250 0.315 0.375 0.500 0.626 0.752 0.874 1.000 1.126 1.252 1.374 1.504 1.626 0.11 0.20 0.31 0.44 0.60 0.79 1.00 1.27 1.56 2.25 4.00 0.155 0.310 0.466 0.777 1.088 1.554 2.332 3.886 0.043 0.078 0.122 0.175 0.239 0.312 0.487 0.761 1.246 1.947 0.049 0.078 0.111 0.196 0.308 0.444 0.600 0.785 0.996 1.231 1.483 1.767 2.077 2 211 lbs/ft D, mm Area, mm 0.376 0.668 1.043 1.502 2.044 2.670 3.400 4.303 5.313 7.650 13.600 0.526 1.052 1.578 2.629 3.681 5.259 7.880 13.150 0.147 0.263 0.415 0.594 0.810 1.057 1.651 2.581 4.227 6.604 0.167 0.263 0.375 0.666 1.044 1.506 2.035 2.664 3.377 4.176 5.029 5.994 7.045 9.5 12.7 15.9 19.1 22.2 25.4 28.7 32.3 35.8 43.0 57.3 11.3 16.0 19.5 25.2 29.9 35.7 43.7 56.4 6.0 8.0 10.0 12.0 14.0 16.0 20.0 25.0 32.0 40.0 6.35 8.0 9.53 12.7 15.9 19.1 22.2 25.4 28.6 31.8 34.9 38.2 41.3 71.3 126.7 198.6 286.5 387.1 506.7 646.9 819.4 1006 1452 2579 100 200 300 500 700 1000 1500 2500 28 50 79 113 154 201 314 491 804 1256 31.67 50 71.33 126.7 198.6 286.5 387.1 506.7 642.4 794.2 956.6 1140 1340 2 kg/m 0.559 0.993 1.557 2.246 3.035 3.973 5.072 6.424 7.887 11.384 20.219 0.784 1.568 2.352 3.920 5.488 7.840 11.76 19.60 0.220 0.392 0.619 0.886 1.207 1.576 2.462 3.849 6.303 9.847 0.248 0.392 0.559 0.993 1.557 2.246 3.035 3.973 5.036 6.227 7.500 8.938 10.506 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Name AS12 AS16 AS20 AS24 AS28 AS32 AS36 NZ6 NZ10 NZ12 NZ16 NZ20 NZ25 NZ32 NZ40 LPile Index No. 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 D, in Area, in 0.472 0.630 0.787 0.945 1.102 1.260 1.417 0.236 0.394 0.472 0.630 0.787 0.984 1.260 1.575 0.175 0.312 0.487 0.701 0.954 1.247 1.578 0.044 0.122 0.175 0.312 0.487 0.761 1.247 1.948 2 lbs/ft D, mm Area, mm 0.596 1.060 1.656 2.384 3.245 4.238 5.364 0.149 0.414 0.596 1.060 1.656 2.587 4.238 6.622 12.0 16.0 20.0 24.0 28.0 32.0 36.0 6.0 10.0 12.0 16.0 20.0 25.0 32.0 40.0 113 201 314 452 616 804 1020 28.3 78.5 113 201 314 491 804 1260 2 kg/m 0.888 1.580 2.470 3.550 4.830 6.310 7.990 0.222 0.617 0.888 1.580 2.470 3.850 6.310 9.860 In addition to the bar sizes shown in the table above, LPile also has generic bar sizes in millimeters ranging from 3 mm to 90 mm. Included in this range of bar diameters are the sizes for high strength bars with diameters of 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 inches. 5-5-2 Prestressing Strand Types and Sizes Name 5/16" 3-wire 1/4 7-wire 5/16 7-wire 3/8 7-wire 7/16 7-wire 1/2" 7-wire 0.6" 7-wire 5/16" 3-wire 3/8 7-wire 7/16 7-wire 1/2" 7-wire 1/2" 7-w spec 9/16" 7-wire 0.6" 7-wire 0.7" 7-wire 3/8" 7-wire 7/16" 7-wire 1/2" 7-wire 1/2" Super 0.6" 7-wire 3/4" smooth 7/8" smooth 1" smooth LPile Index No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Grade, ksi D, in Area, in 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 300 300 300 300 300 145 145 145 0.340 0.250 0.3125 0.375 0.4375 0.500 0.600 0.34 0.375 0.4375 0.500 0.500 0.5625 0.600 0.700 0.375 0.438 0.500 0.500 0.600 0.750 0.875 1.000 0.058 0.036 0.058 0.080 0.108 0.144 0.216 0.058 0.085 0.115 0.153 0.167 0.192 0.217 0.294 0.085 0.115 0.153 0.167 0.217 0.442 0.601 0.785 212 2 lbs/ft D, mm Area, 2 mm kg/m 0.2 0.122 0.197 0.272 0.367 0.49 0.737 0.2 0.29 0.39 0.52 0.58 0.65 0.74 1.01 0.29 0.39 0.52 0.58 0.74 1.5 2.04 2.67 8.6 6.4 7.9 9.5 11.1 12.7 15.2 8.6 9.5 11.1 12.7 12.7 14.3 15.2 17.8 9.5 11.1 12.7 12.7 15.2 19.1 22.2 25.4 37.4 23.2 37.4 51.6 69.7 92.9 138.7 37.4 54.8 74.2 98.7 107.7 123.9 138.7 189.7 54.8 74.2 98.7 107.7 140.0 285.2 387.7 506.5 0.298 0.182 0.293 0.405 0.546 0.729 1.096 0.298 0.431 0.580 0.774 0.863 0.967 1.101 1.505 0.431 0.580 0.774 0.863 1.101 2.232 3.035 3.972 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity 1 1/8" smooth 1 1/4" smooth 1 3/8" smooth Name 3/4" smooth 7/8" smooth 1" smooth 1 1/8" smooth 1 1/4" smooth 1 3/8" smooth 5/8" def. bar 1" def. bar 1" def. bar 1 1/4" def. bar 1 1/4" def. bar 1 3/8" def. bar 24 25 26 LPile Index No. 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 145 145 145 1.125 1.250 1.375 0.994 1.227 1.485 Grade, ksi D, in Area, in 160 160 160 160 160 160 157 150 160 150 160 160 0.75 0.875 1 1.125 1.25 1.375 0.625 1 1 1.25 1.25 1.375 0.442 0.601 0.785 0.994 1.227 1.485 0.28 0.85 0.85 1.25 1.25 1.58 2 3.38 4.17 5.05 28.6 31.8 34.9 641.3 791.6 958.1 5.029 6.204 7.513 lbs/ft D, mm Area, 2 mm kg/m 1.5 2.04 2.67 3.38 4.17 5.05 0.98 3.01 3.01 4.39 4.39 5.56 19.1 22.2 25.4 28.6 31.8 34.9 15.9 25.4 25.4 31.8 31.8 34.9 285.2 387.7 506.5 641.3 791.6 958.1 180.6 548.4 548.4 806.5 806.5 1019.4 2.232 3.035 3.972 5.029 6.204 7.513 1.458 4.478 4.478 6.531 6.531 8.272 5-5-3 Steel H-Piles Section HP 14 HP 360 HP 13 HP 330 HP 12 HP 310 Weight Area, A Depth, d lbs/ft kg/m in2 cm2 in mm 117 34.4 175 222 102 30 Thickness Flange Width, b Ixx Iyy in4 cm4 in4 cm4 Compact Section Criteria F'y ksi MPa in mm Flange, tf in. mm Web, tw in. mm 14.21 14.885 0.805 0.805 1220 443 361 378 20.4 20.4 50800 18400 341 14.01 14.785 0.705 0.705 1050 380 38.4 49.4 153 194 356 376 17.9 17.9 43700 15800 265 89 26.1 13.83 14.695 0.615 0.615 904 326 29.6 133 168 351 373 15.6 15.6 37600 13600 204 20.3 73 21.4 13.61 14.585 0.505 0.505 729 261 109 138 346 370 12.8 12.8 30300 10900 140 100 29.4 13.15 13.205 0.765 0.765 886 294 56.7 150 190 334 335 19.4 19.4 36878 12237 391 87 25.5 12.95 13.105 0.665 0.665 755 250 43.5 130 165 329 333 16.9 16.9 31425 10406 300 31.9 73 21.6 12.75 13.005 0.565 0.565 630 207 109 139 324 330 14.4 14.4 26223 8616 220 60 17.5 12.54 12.9 0.46 0.46 503 165 21.5 90 113 319 328 11.7 11.7 20936 6868 148 52.5 84 24.6 12.28 12.295 0.685 0.685 650 213 126 159 312 312 17.4 17.4 27100 8870 362 74 21.8 12.13 12.215 0.61 0.61 569 186 42.1 111 141 308 310 15.5 15.5 23700 7740 290 63 18.4 11.94 12.125 0.515 0.515 472 153 30.5 94 119 303 308 13.1 13.1 19600 6370 210 213 Chapter 5 – Computation of Nonlinear Bending Stiffness and Moment Capacity Section HP10 HP 250 HP 8 HP 200 53 15.5 11.78 12.045 0.435 0.435 393 127 22 79 100 299 306 11 11 16400 5290 152 Weight Area, A Depth, d lbs/ft kg/m in2 cm2 in mm 57 16.8 85 108 42 63 Flange Width, b Ixx Iyy in4 cm4 in4 cm4 294 101 Compact Section Criteria F'y ksi MPa 51.6 12200 4200 356 29.4 Thickness in mm Flange, tf in. mm 9.99 10.225 0.565 Web, tw in. mm 0.565 254 260 14.4 14.4 12.4 9.7 10.075 0.42 0.42 210 71.7 80 246 256 10.7 10.7 8740 2980 203 36 10.6 8.02 8.155 0.445 0.445 119 40.3 50.3 54 68.4 204 207 11.3 11.3 4950 1680 347 214 Chapter 6 Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope 6-1 Introduction The computation of slope stability is a problem often faced by geotechnical engineers. Numerous computer methods have been developed for making the slope stability computation. One of the first of these available as a computer solution was the simplified method of slices developed by Bishop (1955). Over the years, there have been additional developments for analyzing slope stability. The method of Morgenstern and Price (1965) was the first method of analysis that was capable of solving all equations of force and moment equilibrium for a limit analysis of slope stability. The widely used computer programs UTexas4, Slope/W, and Slide implement modern developments in computation of slope stability. In view of advances in methods of analysis, the availability of computer programs, and numerous comparisons of results of analysis and observed slope failures, many engineers will obtain approximately identical factors of safety for a particular problem of slope stability. This chapter is written with the assumption that the user is familiar with the theory of slope stability computations and has a computer program available for use. In spite of the ability to make reasonable computations, there are occasions when engineering judgment may indicate the need to increase the factor of safety for a particular slope. There are a large number of methods for accomplishing such a purpose. For example, the factor of safety may be increased by flattening the slope, if possible, or by providing subsurface drainage to lower the water table in the slope. The method proposed in this chapter presents the engineer with additional option that might prove useful in some cases. Piles have been used in the past to increase the stability of a slope, but without an analysis to judge their effectiveness. Thus, a method of analysis to investigate the benefits of using piles for this purpose is a useful tool for engineers. 6-2 Proposed Methods Any number of situations could develop that might dictate the use of piles to increase the stability of a slope. A common occurrence is the appearance of cracks parallel to the crest of the slope. Cracks of this type often indicate the initial movement associate with slope failure and can provide a means for surface water to enter the soil and saturate the slope. This could result in a reduced factor of safety for slope stability in the future. Slope stability analysis may show that the factor of safety for the slope is near unity and some strengthening of the slope is needed before additional slope movement occurs. One possible solution is shown in Figure 6-1. In this method, a row of drilled shafts or piles is constructed in the slope near the position of the lowest extent of the sliding surface. The use of a drilled foundation is a favorable procedure because the installation of the shaft will result in minimal disturbance to the soils in the slope. 215 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope Even if no distress may appear in a slope, analysis of some slopes after construction may show the stability of a slope is questionable. The original slope stability analysis may be superseded by a more accurate one, additional soil borings or construction may reveal a weak stratum that was not found earlier, or changes in environmental conditions could have caused a weakening of the soils in the slope. The use of drilled shaft foundations to strengthen the slope might then be considered. Figure 6-1 Scheme for Installing a Row of Piles in a Slope Subject to Sliding A second scheme for the positioning of piles is shown in Figure 6-2. In this scheme, the tops of one or more rows of stabilizing piles are restrained by a structural grade beam connected to an anchor pile group. In this scheme, it is possible for the stabilizing piles to carry more loading because they are restrained at the top by the grade beam and anchor pile group and the stable soils below the slip surface. Structural Grade Beam Anchor Pile Group Stabilizing Piles Figure 6-2 Scheme for Stabilizing Piles with Grade Beam and Anchor Pile Group 216 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope Available right-of-way in urban areas may be limited or extremely expensive to purchase with the result that the design of a slope with an adequate factor of safety against sliding is impossible or very expensive. A cost study could reveal whether or not it would be preferable to install a retaining wall or to strengthen the slope with drilled shafts. 6-3 Review of Some Previous Applications Fukuoka (1977) described three applications where piles were used to stabilize slopes in Japan. Heavily steel pipe piles were used at Kanogawa Dam to stabilize a landslide. A series of steel pipe piles, 458 mm (18 inches) in diameter were driven in pairs, 5 m (16.4 ft) apart, through pre-bored holes near the toe of the slide. A plan view of the supporting structure showed that it extended about 1,100 meters (3,600 ft) in a generally circular pattern. The installation, along with a drainage tunnel, apparently stabilized the slide. A slide developed at the Hokuriku Expressway in Fukue Prefecture when a cut to a depth of 30 m (98 ft) was made. The cut extended to about 170 meters from the centerline of the highway and was about 100 meters (328 ft) in length. After movement of the slope was observed, a row of H-piles was installed, but the piles were damaged by an increased by an increase of the velocity of movement of the slide due to a torrential downpour. Subsequently, drainage of the slope was improved and four rows of piles were installed parallel to the slope to stabilize the slide. Analyses showed that the factor of safety against sliding was increased from near unity to 1.3. Fukuoka reported that there were numerous examples in Niigata Prefecture where piles had been used to stabilize landslides. A detailed discussion was presented about the use of piles at the Higashi-tono landslide. The length of the slide in the direction of the slope was about 130 meters (427 ft), its width was about 40 meters (131 ft), and the sliding surface was found to be about 5 meters (16.4 ft) below the ground surface. A total of 100 steel pipe piles, 319 mm (12.6 in.) in diameter were installed in the slide over a period of three years. Computations indicated that the presence of the piles increased the factor of safety against sliding by about 0.18, which was sufficient to prevent further movement. Strain gages were installed on five of the piles and these piles were recovered after some time. Two of the piles were fractured due to excessive bending moment. Hassiotis and Chameau (1984) and Oakland and Chameau (1986) present brief descriptions of a large number of cases where piles have been used to stabilize slopes. The authors present a detailed discussion of the use of piles and drilled piers in the stabilization of slopes. 6-4 Analytical Procedure A drawing of a pile embedded in a slope is shown in Figure 6-3(a) where the depth to the sliding surface is denoted by the symbol hp. The distributed lateral forces from the sliding soil are shown by the arrows, parallel to the slope in Figure 6-3(b). The resultant of the horizontal components of the forces from the sliding soil is denoted by the symbol Fs. The loading for the portion of the pile in stable soil are denoted in Figure 6-3(c) as a shear P and moment M. The portion of the pile below the sliding surface is caused to deflect laterally by P and M and the resisting forces from the soil are shown in the lower section of 217 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope Figure 6-3(b). The behavior of the pile can be found by the procedures shown earlier for piles under lateral loading and the assumptions discussed in the following paragraph. M hp P (a) (b) (c) Figure 6-3 Forces from Soil Acting Against a Pile in a Sliding Slope, (a) Pile, Slope, and Slip Surface Geometry, (b) Distribution of Mobilized Forces, (c) Free-body Diagram of Pile Below the Slip Surface The principles of limit equilibrium are usually employed in slope stability analysis. The influence of stabilizing piles on the factor of safety against sliding is illustrated in Figure 6-4. The resultant of the resistance of the pile, T can be included in the analysis of slope stability. Therefore, a consistent assumption is that the sliding soil has moved a sufficient amount that the peak resistance from the soil has developed against the pile. If one considers the force acting on a pile from a wedge of soil with a sloping surface, the force parallel to the soil surface is larger than if the surface were horizontal. However, a reasonable assumption is that the peak resistance acting perpendicular to the pile can be found from the p-y curve formations presented in Chapter 3. 218 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope R z T Safety factor for moment equilibrium considering the same forces as above, plus the effect of the stabilizing pile is expressed as: F cLR P uLR tan Tz WX ......................................(6-1) Where T is the average total force per unit length horizontally resisting soil movement and z is the distance from the centroid of resisting pressure to center of rotation. Figure 6-4 Influence of Stabilizing Pile on Factor of Safety Against Sliding The discussion above leads to the following step-by-step procedure: 1. Find the factor of safety against sliding for the slope using an appropriate computer program. 2. At the proposed position for the stabilizing pile, tabulate the relevant soil properties with depth. 3. Select a pile with a selected diameter and structural properties and compute the bending stiffness and nominal moment capacity. Compute the ultimate moment capacity (i.e. factored moment capacity) by multiplying by an appropriate strength reduction factor (typically around 0.65) 4. Assume that the sliding surface is the same as found in Step 1, then use LPile to compute the p-y curves at selected depths above the sliding surface. Employ the peak soil reaction versus depth as a distributed lateral force for depths above the sliding surface as shown in Figure 6-3(b) and analyze the pile again using LPile. 5. Compare the maximum bending moment found in Step 4 with the nominal moment capacity from Step 3. At this point, an adjustment of the size or geometry of the pile may or may not be made, depending on the results of the comparison. Note that in general, the presence of the piles may change the position of the sliding surface, which will also change the maximum bending moment developed in the pile. However, in some cases, 219 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope the position of the sliding surface will be known because of the location of a weak soil layer, and, in any case, it is unlikely that the position of the sliding surface will be changed significantly by the presence of the piles. 6. Employ the resisting shear and moment in the slope stability analysis used in Step 1 and find the new position of the sliding surface. While only one pile is shown in Figure 6-4, one or more rows of piles are most likely to be used. In such a case, the forces due to a single pile should be divided by the center-to-center spacing along the row of piles prior to input to the slope stability analysis program because the two-dimensional slope stability analysis is written assuming that the thickness of the third dimension is one unit. Some programs for slope stability analysis can use the profile of distributed loads in the computation of the new sliding surface. 7. Change the depth of sliding, hp, to the depth of sliding employed in Step 4, obtain new values of M and P, and repeat the analyses until agreement is found between that surface and the resisting forces for the piles. Also, the geometry of the piles should be adjusted so that the maximum bending moment found in the analyses is close to the ultimate moment capacity of the piles. 8. Finally, compare the factor of safety against sliding of the slope with no piles to that with piles in place and determine whether or not the improvement in factor of safety justifies the use of the piles. 1 Computed hp 1 Assumed hp Figure 6-5 Matching of Computed and Assumed Values of hp 6-5 Alternative Method of Analysis In the method discussed above, the stabilizing force provided by the piles was based on the peak lateral resistance from the formation of the p-y curves. In some cases, an alternative approach might be used that is based on an analysis with LPile using the soil movement option. In this method, the user can draw the geometry of the slope failure and estimate the magnitude of 220 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope soil movement along a vertical alignment at the centerline of the stabilizing pile. The evaluation of stabilizing forces then proceeds in the manner discussed previously. If the soil movements are small, the magnitude of stabilizing forces is likely to be smaller than those computed before. The advantage of using this more conservative method is that the magnitude of the slope movement needed to mobilize the stabilizing forces is smaller. Thus, if the factor of safety for the slope is raised to an acceptable level, less distortion of the slope after installation of the stabilizing piles will occur. 6-6 Case Studies and Example Computation 6-6-1 Case Studies Fukuoka (1977) described a field experiment that was performed at the landslide at Higashi-tono in the Niigata Prefecture. A pile, instrumented with strain gages, was installed in a slide that continued to move at a slow rate. The moving soil was a mudstone and the N-value from the Standard Penetration Test, NSPT, near the sliding surface was found to be 20 bpf. The pile was 22 m in length, had an outer diameter of 406 mm, and had a wall thickness of 12.7 millimeters. The bending moment in the pile increased rapidly after installation and appeared to have reached the maximum value after being in place about three months. The strain gages showed the maximum bending moment to occur at a depth of about 10 m below the ground surface and to be about 220 kN-meters. The maximum bending stress in the pile, thus, was about 1.5 105 kPa, a value that shows the loading on the pile from the sliding soil to be very low. Therefore, it was concluded that the driving force from the moving soil was far from its maximum value. The positive conclusion from this field test is that the bending-moment curve given by Fukuoka had the general shape that would be expected. At another site at the Higashi-tono landslide, Fukuoka described an experiment where a number of steel-pipe piles were used in a sliding soil. Some of them were removed after a considerable period of time and found to have failed in bending. One of them had a diameter of 318.5 mm and a wall thickness of 10.3 mm. The collapse moment for the pipe was computed to be 241 kN-m. Assuming a triangular distribution of earth pressure on the pile from the sliding mass of soil, which had a thickness of 5 m, the undrained shear strength that was required to cause the pile to fail was 10.7 kPa. The author merely stated that the soil had a NSPT that was less than 10 bpf. That value of NSPT probably reflects an undrained shear strength that encompasses the computed strength to cause the pile to fail. 6-6-2 Example Computation The example that was selected for analysis is shown in Figure 6-6. The slope exists along the bank of a river where rapid drawdown is possible. Prior slope failures had been observed at numerous places along the river and it was desired to stabilize the slope to allow a bridge to be constructed. 221 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope Elevation, m 80 75 Fill c = 47.9 kPa = 19.6 kN/m3 70 Silt c = 23.9 kPa cresidual =12.4 kPa = 17.3 kN/3m3 65 60 Clay c = 36.3 kPa = 17.3 kN/m3 Sand = 19.6 kN/m3 = 30 to 40 deg. 55 Figure 6-6 Soil Conditions for Analysis of Slope for Low Water The undrained analysis for the sudden-drawdown case was made based on the Spencer's method, and the factor of safety was found to be 1.06, a value that is in reasonable agreement with observations. Plainly, some method of design and construction would be necessary in order for bridge piers to be placed at the site. The method described herein was employed to select sizes and spacing of drilled shafts that could be used to achieve stability. A preliminary design is shown in Figure 6-7, but not shown in the figure is the distance along the river for which the slope was to be stabilized. Drilled shafts were selected that were 915 mm (3 ft) in diameter and penetrated well below the sliding surface, as shown in the figure. Furthermore, it was found that the tops of the shafts had to be restrained by a grade beam connected to anchor piles outside of the slide zone. The use of the grade beam was required because of the depth of the slide. The stabilizing piles were modeled with restrained pile heads to model the effect of the pile-head connection to the grade beam. The results of the analysis, for each of the pile groups perpendicular to the river, gave the following loads at the top of the drilled shafts: Rows 1, 2, and 3, +1,090 kN/shaft; Row 4, –1,310 kN/shaft; and Row 5, –1,690 kN/shaft. The grade beam connecting the tops of the five rows of piles would be designed to sustain the indicated loading. The maximum bending moment computed for shafts in Row 5 on the extreme right was 6,250 kN-m. This level of moment required heavy reinforcement in the shaft. The computed bending moments for the other drilled shafts were much smaller. With the piles in place and with the restraining forces of the piles against the sliding soil, shown Figure 6-8, a second analysis was performed to find the new factor of safety against sliding. The new factor of safety that was obtained was 1.82. This result was sufficient to show that the technique was feasible. However, in a practical design, a series of analyses would have been performed to find the most economical geometry and spacing for the piles in the group. 222 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope Pile Row 1 2 3 4 5 5.5 m Pile diameter 915 mm Grade Beam 30 m 4.6 m 4.6 m 15.2 m 15.2 m Figure 6-7 Preliminary Design of Stabilizing Piles Elevation, m 80 48 kPa 48 kPa 75 70 108 kPa 108 kPa 65 71 kPa 71 kPa 60 55 Figure 6-8 Load Distribution from Stabilizing Piles for Slope Stability Analysis 223 Chapter 6 – Use of Vertical Piles to Stabilize a Slope 6-6-3 Conclusions The results predicted by the proposed design method were compared with results from available full-scale experiments. The case studies yielded information on the applicability of the proposed method of analysis. A complete analysis for the stability of slopes with drilled shafts in place was presented. The proposed method of analysis is considered practical and can be implemented by engineers by using readily available methods of analysis. The benefits of using the method is that rationality and convenience are provided that were not previously available. 224 References Akinmusuru, J. O., 1980. “Interaction of Piles and Cap in Piled Footings, Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 106, No. GT11, November, pp. 1263-1268. Allen, J., 1985. “p-y Curves in Layered Soils,” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, May. American Petroleum Institute, 2010. Recommended Practice for Planning, Designing and Constructing Fixed Offshore Platforms - Working Stress Design, API RP 2A-WSD, 21st Edition, Errata and Supplement, 2010. Ashford, S. A.; Boulanger, R. J.; and Brandenberg, S. J., 2011. “Recommended Design Practice for Pile Foundations in Laterally Spreading Ground,” PEER Report 2011/04, Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California, Berkeley, June, 44 p. Awoshika, K., and Reese, L. C., 1971. “Analysis of Foundation with Widely-Spaced Batter Piles,” Research Report 11 7-3F, Center for Highway Research, The University of Texas at Austin, February. Awoshika, K., and Reese, L. C., 1971. “Analysis of Foundations with Widely Spaced Batter Piles,” Proceedings, Intl. Symposium on the Engineering Properties of Sea-Floor Soils and Their Geophysical Identification, University of Washington, Seattle. Baecher, G. B., and Christian, J. T., 2003. Reliability and Statistics in Geotechnical Engineering, Wiley, New York, 605 p. Baguelin, F.; Jezequel, J. F.; and Shields, D. H., 1978. The Pressuremeter and Foundation Engineering, Trans Tech Publications. Bhushan, K.; Haley, S. C.; and Fong, P. T., 1979. “Lateral Load Tests on Drilled Piers in Stiff Clay,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 105, No. GT8, pp. 969-985. Bhushan, K.; Lee, L. J.; and Grime, D. B., 1981. “Lateral Load Test on Drilled Piers in Sand,” Preprint, ASCE Annual Meeting, St. Louis, Missouri. Bishop, A.W. 1955. “The Use of the Slip Circle in the Stability Analysis of Slopes,” Géotechnique, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 7-17 Bogard, D., and Matlock, H., 1983. “Procedures for Analysis of Laterally Loaded Pile Groups in Soft Clay,” Proceedings, Geotechnical Practice in Offshore Engineering, ASCE. Bowman, E. R., 1959. “Investigation of the Lateral Resistance to Movement of a Plate in Cohesionless Soil,” M.S. thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, January, 84 p. Briaud, J.-L.; Smith, T. D.; and Meyer, B. J., 1982. “Design of Laterally Loaded Piles Using Pressuremeter Test Results,” Symposium, The Pressuremeter and Marine Applications, Paris. Broms, B. B., 1964a. “Lateral Resistance of Piles in Cohesionless Soils,” Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 90, No. SM3, pp. 123-156. 225 References Broms, B. B., 1964b. “Lateral Resistance of Piles in Cohesive Soils,” Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 90, No. SM2, pp. 27-63. Broms, B. B., 1965. “Design of Laterally Loaded Piles,” Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 91, No. SM3, pp. 79-99. Brown, D. A., 2002. Personal Communication about “Specifying Initial k for Stiff Clay with No Free Water. “ Brown, D. A.; Morrison, C. M.; and Reese, L. C., 1988. “Lateral Load Behavior of a Pile Group in Sand,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 114, No. 11, pp. 1261-1276. Brown, D. A.; Reese, L. C.; and O’Neill, M. W., 1987. “Cyclic Lateral Loading of a Large-Scale Pile Group,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 113, No. 11, pp. 1326-1343. Brown, D. A.; Shie, C. F.; and Kumar, M., 1989. “p-y Curves for Laterally Loaded Piles Derived from Three-Dimensional Finite Element Model,” Proceedings, 3rd Intl. Symposium, Numerical Models in Geomechanics, Niagara Falls, Canada, Elsevier Applied Science, pp. 683-690. Bryant, L. M., 1977. “Three Dimensional Analysis of Framed Structures with Nonlinear Pile Foundations”, Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, 95 p. California Department of Transportation, 2011. “Guidelines on Foundation Loading and Deformation Due to Liquefaction Induced Lateral Spreading,” January, 45 p. Cox, W. R.; Dixon, D. A.; and Murphy, B. S., 1984. “Lateral Load Tests of 25.4 mm Diameter Piles in Very Soft Clay in Side-by-Side and In-Line Groups,” Laterally Loaded Deep Foundations: Analysis and Performance, ASTM, SPT835. Cox, W. R.; Reese, L. C.; and Grubbs, B. R., 1974. “Field Testing of Laterally Loaded Piles in Sand,” Proceedings, 6th Offshore Technology Conference, Vol. II, pp. 459-472. Darr, K.; Reese, L. C.; and Wang, S.-T., 1990. “Coupling Effects of Uplift Loading and Lateral Loading on Capacity of Piles,” Proceedings, 22nd Offshore Technology Conference, pp. 443450. Det Norske Veritas, 1977. Rules for the Design, Construction, and Inspection of Offshore Structures, Veritasveien 1, 1322 Høvik, Norway. DiGiola, A. M.; Rojas-Gonzalez, L.; and Newman, F. B., 1989. “Statistical Analyses of Drilled Shaft and Embedded Pole Models,” Proceedings, Foundation Engineering: Current Principals and Practices, ASCE, Vol. 2, pp. 1338-1352. Dunnavant, T. W., and O’Neill, M. W., 1985. “Performance, Analysis, and Interpretation of a Lateral Load Test of a 72-Inch-Diameter Bored Pile in Over-consolidated Clay,” Department of Civil Engineering, University of Houston-University Park, Houston, Texas, Report No. UHCE 85-4, September, 57 pages. Evans, L. T., and Duncan, J. M., 1982. “Simplified Analysis of Laterally Loaded Piles,” Report No. UCB/GT/82-04, Geotechnical Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, University of California, Berkeley. 226 References Focht, J. A., Jr. and Koch, K. J., 1973. “Rational Analysis of the Lateral Performance of Offshore Pile Groups,” Proceedings, 5th Offshore Technology Conference, Vol. II, pp. 701708. Franke, K. W., and Rollins, K. M., 2013. “Simplified Hybrid p-y Spring Model for Liquefied Soils,” Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 139, No. 4, pp. 564-576. Fukuoka, M., 1977. “The Effects of Horizontal Loads on Piles Due to Landslides,” Proceedings, 9th International Conference, ISSMFE, Tokyo, Japan. Gazioglu, S. M., and O’Neill, M. W., 1984. “Evaluation of p-y Relationships in Cohesive Soil,” Symposium on Analysis and Design of Pile Foundations, ASCE, San Francisco, 192-213. George, P., and Wood, D., 1976. Offshore Soil Mechanics, Cambridge University Engineering Department. Georgiadis, M., 1983. “Development of p-y Curves for Layered Soils,” Proceedings, Geotechnical Practice in Offshore Engineering, ASCE, pp. 536-545. Hansen, J. B., 1961. “A General Formula for Bearing Capacity,” Bulletin No. 11, The Danish Geotechnical Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark, pp. 3 8-46. Hansen, J. B., 1961. “The Ultimate Resistance of Rigid Piles Against Transversal Forces,” Bulletin No. 12, The Danish Geotechnical Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark, pp. 5-9. Hassiotis, S. and Chameau, J. L. 1984. “Stabilization of Slopes Using Piles,” Report No. FHWA/IN/JHRP-84/8, Purdue University, 181 p. Hetenyi, M., 1946. Beams on Elastic Foundation, University of Michigan Press, 255 p. Hoek, E., 1990. “Estimating Mohr-Coulomb Friction and Cohesion Values from the HoekBrown Failure Criterion,” International Journal of Rock Mechanics, Mining Sciences, and Geomechanics Abstracts, 27 (3), pp. 227-229. Hoek, E., 2001. “Rock Mass Properties for Underground Mines,” Underground Mining Methods: Engineering Fundamentals and International Case Studies, Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration. Hoek, E., and Brown, E. T., 1980. “Empirical Strength Criterion for Rock Masses,” Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 106, pp. 1013-1035. Horvath, R. G., and Kenney, T. C., 1979. “Shaft Resistance of Rock-Socketed Drilled Piers,” Proceedings, Symposium on Deep Foundations, ASCE, pp. 182-184. Hrennikoff, A., 1950. “Analysis of Pile Foundations with Battered Piles,” Transactions, ASCE, Vol. 115, pp. 351-374. Isenhower, W. M., 1992. “Reliability Analysis for Deep-Seated Stability of Pile Foundations,” Report to Department of the Army, Waterways Experiment Station, Corps of Engineers, Contract No. DAAL03-91-C-0034, TCN 92-185, Scientific Services Program, 67 p. Isenhower, W. M., 1994. “Improved Methods for Evaluation of Bending Stiffness of Deep Foundations,” Proceedings, Intl. Conf. on Design and Construction of Bridge Foundations, Vol. 2, pp. 571-585. 227 References Ismael, N. F., 1990. “Behavior of Laterally Loaded Bored Piles in Cemented Sands,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 116, No. 11, pp. 1678-1699. Jamiolkowski, M., 1977. “Design of Laterally Loaded Piles,” Intl. Conf. on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Tokyo. Japanese Society for Architectural Engineering, Committee for the Study of the Behavior of Piles During Earthquakes, 1965. “Research Concerning Horizontal Resistance and Dynamic Response of Pile Foundations,” (in Japanese). Johnson, G. W., 1982. “Use of the Self-Boring Pressuremeter in Obtaining In-Situ Shear Moduli of Clay,” M.S. Thesis, The University of Texas, Austin, Texas, August, 156 p. Johnson, R. M., Parsons, R. L., Dapp, S. D., and Brown, D. A., 2006. “Soil Characterization and p-y Curve Development for Loess,” Kansas Department of Transportation, Bureau of Materials and Research, July. Kooijman, A. P., 1989. “Comparison of an Elasto-plastic Quasi Three-Dimensional Model for Laterally Loaded Piles with Field Tests,” Proceedings, 3rd Intl. Symposium, Numerical Models in Geomechanics, Elsevier Applied Science, New York, pp. 675-682. Kubo, K., 1964. “Experimental Study of the Behavior of Laterally Loaded Piles,” Report, Transportation Technology Research Institute, Japan, Vol. 12, No. 2. Kulhawy, F. H. and Phoon, K. K. 1993. “Drilled Shaft Side Resistance In Clay Soil to Rock,” Design & Performance of Deep Foundations: Piles & Piers in Soil & Soft Rock (GSP 38), ASCE, New York, Oct 1993, 172-183. Liang, R.; Yang, K.; and Nusairat, J., 2009. “ p-y Criterion for Rock Mass,” Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, Vol. 135, No. 1, pp. 26-36. Lieng, J. T., 1988. “Behavior of Laterally Loaded Piles in Sand - Large Scale Model Tests,” Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Civil Engineering, Norwegian Institute of Technology, 206 p. Long, J. H., 1984. “The Behavior of Vertical Piles in Cohesive Soil Subjected to Repetitive Horizontal Loading,” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas, Austin, Texas, 332 p. Malek, A. M.; Azzouz, A. S.; Baligh, M. M.; and Germaine, J. T., 1989. “Behavior of Foundation Clays Supporting Compliant Offshore Structures,” Journal of Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 115, No. 5, pp. 615-637. Marinos, P., and Hoek, E., 2000. “GSI – A Geologically Friendly Tool for Rock Mass Strength Estimation,” Proceedings, GeoEngineering 2000 Conference, Melbourne, pp.1,422-1,442. Matlock, H., 1970. “Correlations for Design of Laterally Loaded Piles in Soft Clay,” Proceedings, 2nd Offshore Technology Conference, Vol. I, pp. 577-594. Matlock, H., and Ripperger, E. A., 1958. “Measurement of Soil Pressure on A Laterally Loaded Pile,” Proceedings, ASTM, Vol. 58, pp. 1245-1259. Matlock, H.; Ripperger, E. A.; and Fitzgibbon, D. P. 1956. “Static and Cyclic Lateral-Loading of an Instrumented Pile,” Report to Shell Oil Company (unpublished), 167 p. 228 References McClelland, B., and Focht, J. A., 1956. “Soil Modulus for Laterally Loaded Piles,” Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Division, ASCE, No. SM4, October, Paper 1081, 22 p., also published in Transactions, ASCE, 1958, Vol. 123, pp. 1049-1086. Morgenstern, N. R. and Price, V. E., 1965. “The Analysis of the Stability of General Slip Surfaces,” Géotechnique, No. 1, Vol. 15, pp. 79-93. O’Neill, M. W., 1996. Personal Communication. O’Neill, M. W., and Dunnavant, T. W., 1984. “A Study of the Effects of Scale, Velocity, and Cyclic Degradability on Laterally Loaded Single Piles in Overconsolidated Clay,” Report No. UHCE 84-7, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Houston-University Park, Houston, 368 p. O’Neill, M. W., and Gazioglu, S. M., 1984. “An Evaluation of p-y Relationships in Clays,” Report to the American Petroleum Institute, PRAC 82-41-2, The University of HoustonUniversity Park, Houston. O’Neill, M. W., and Murchison, J. M., 1983. “An Evaluation of p-y Relationships in Sands,” Report to the American Petroleum Institute, PRAC 82-41-1, The University of HoustonUniversity Park, Houston. O’Neill, M. W.; Ghazzaly, O. I.; and Ha, H. B., 1977. “Analysis of Three-Dimensional Pile Groups with Nonlinear Soil Response and Pile-Soil-Pile Interaction,” Proceedings, 9th Offshore Technology Conference, Vol. II, pp. 245-256. Oakland, M. W. and Chameau, J. L. 1986. “Drilled Piers Used for Slope Stabilization,” Report No. FHWA/IN/JHRP-86/7, Purdue University, 305 p. Parker, F., Jr., and Reese, L. C., 1971. “Lateral Pile-Soil Interaction Curves for Sand,” Proceedings, Intl. Symposium on the Engineering Properties of Sea-Floor Soils and Their Geophysical Identification, The University of Washington, Seattle, pp. 212-223. Poulos, H. G., and Davis, E. H. 1980. Pile Foundation Analysis and Design, Wiley, New York. Reese, L. C., 1958. “Discussion of “Soil Modulus for Laterally Loaded Piles,” by B. McClelland and J. A. Focht, Jr., Transactions, ASCE, Vol. 123, pp. 1071-1074. Reese, L. C., 1984. Handbook on Design of Piles and Drilled Shafts under Lateral Load, Report FHWA-IP84-11, FHWA, US Department of Transportation, Office of Research, Development and Technology, McLean, Virginia, , July, 1984, 360 p. Reese, L. C., 1985. Behavior of Piles and Pile Groups Under Lateral Load, Report No. FHWA/RD-85/106, Federal Highway Administration, Office of Research, Development, and Technology, Washington, DC. Reese, L. C., 1988. “Response of Piles in Calcareous Soils to Lateral Loading,” Proceedings, Conference on Engineering for Calcareous Sediments, Vol. 2, North Rankin “A” Foundation Project, State of the Art Reports, Balkema, pp. 859-866. Reese, L. C., 1997. “Analysis of Piles in Weak Rock,” Journal of the Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering Division, ASCE, pp. 1010-1017. Reese, L. C., and Cox, W. R., 1968. “Soil Behavior from Analysis of Tests of Uninstrumented Piles Under Lateral Loading,” ASTM Special Technical Publication 444, pp. 160-176. 229 References Reese, L. C., and Matlock, H., 1956. “Non-Dimensional Solutions for Laterally Loaded Piles with Soil Modulus Assumed Proportional to Depth,” Proceedings, 8th Texas Conf. on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Special Publication No. 29, Bureau of Engineering Research, The University of Texas, 1956, 41 pages. Reese, L. C., and Nyman, K. J., 1978. “Field Load Test of Instrumented Drilled Shafts at Islamorada, Florida,” Report to Girdler Foundation and Exploration Corporation, Clearwater, Florida, (unpublished). Reese, L. C., and Van Impe, W. F., 2011. Single Piles and Pile Groups Under Lateral Loading, 2nd Edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 507 p. Reese, L. C., and Wang, S.-T. 1988. “The Effect of Nonlinear Flexural Rigidity on the Behavior of Concrete Piles Under Lateral Loading,” Texas Civil Engineer, May, pp. 17-23. Reese, L. C., and Welch, R. C., 1975. “Lateral Loading of Deep Foundations in Stiff Clay,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 101, No. GT7, pp. 633-649. Reese, L. C.; Cox, W. R.; and Koop, F. D., 1968. “Lateral-Load Tests of Instrumented Piles in Stiff Clay at Manor, Texas,” Report to Shell Development Company (unpublished), 303 p. Reese, L. C.; Cox, W. R.; and Koop, F. D., 1974. “Analysis of Laterally Loaded Piles in Sand,” Proceedings, 6th Offshore Technology Conference, Vol. II, pp. 473-484. Reese, L. C.; Cox, W. R.; and Koop, F. D., 1975. “Field Testing and Analysis of Laterally Loaded Piles in Stiff Clay,” Proceedings, 7th Offshore Technology Conference, pp. 671-690. Reese, L. C.; Wang, S.-T.; and Long, J. H. 1989. “Scour from Cyclic Lateral Loading of Piles,” Proceedings, 21st Offshore Technology Conference, pp. 395-401. Rollins, K. M.; Gerber, T. M.; Lane, J. D.; and Ashford, S. A., 2005a. “Lateral Resistance of a Full-Scale Pile Group in Liquefied Sand”, Journal of the Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 131, pp. 115-125. Rollins, K. M.; Hales, L. J.; and Ashford, S. A. 2005b. “p-y Curves for Large Diameter Shafts in Liquefied Sands from Blast Liquefaction Tests,” Seismic Performance and Simulation of Pile Foundations in Liquefied and Laterally Spreading Ground, Geotechnical Special Publication No. 145, ASCE, p. 11-23. Rowe, R. K., and Armitage, H. H., 1987. “A Design Method for Drilled Piers in Soft Rock,” Canadian Geotechnical Journal, Vol. 24, pp. 126-142. Schmertmann, J. H., 1977. “Report on Development of a Keys Limestone Shear Test for Drilled Shaft Design,” Report to Girdler Foundation and Exploration Corporation, Clearwater, Florida, (unpublished). Seed, R. B. and Harder, L. F., 1990. “SPT-Based Analysis of Cyclic Pore Pressure Generation and Undrained Residual Strength,” H. Bolton Seed, Memorial Symposium, Vol. 2, BiTech Publishers Ltd., pp. 351-376 Sherard, J. L.; Dunnigan, L. P.; and Decker, R. S., 1976. “Identifying Dispersive Soils,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, ASCE, Vol. 102, No. GT1, pp. 69-86. Simpson, M. and Brown, D. A., 2006. Personal Communication. 230 References Skempton, A. W., 1951. “The Bearing Capacity of Clays,” Proceedings, Building Research Congress, Division I, Building Research Congress, London. Speer, D., 1992. “Shaft Lateral Load Test Terminal Separation,” Unpublished report, California Department of Transportation. Stevens, J. B., and Audibert, J. M. E., 1979. “Re-examination of p-y Curve Formulation,” Proceedings, 11th Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, Vol. I, pp. 397-403. Stokoe, K. H., 1989. Personal Communication, October. Sullivan, W. R.; Reese, L. C.; and Fenske, C. W., 1980. “Unified Method for Analysis of Laterally Loaded Piles in Clay,” Numerical Methods in Offshore Piling, Institution of Civil Engineers, London, pp. 135-146. Terzaghi, K., 1955. “Evaluation of Coefficients of Subgrade Modulus,” Géotechnique, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 297-326. Thompson, G. R., 1977. “Application of the Finite Element Method to the Development of p-y Curves for Saturated Clays,” M.S. thesis, The University of Texas at Austin. Timoshenko, S. P., 1956. Strength of Materials, Part II, Advanced Theory and Problems, 3rd Edition, Van Nostrand, New York, 572 p. Vesić, A. S., 1961. “Bending of Beams Resting on Isotropic Elastic Solids,” Journal of the Engineering Mechanics Division, ASCE, Vol. 87, No. EN2, pp. 35-53. Wang, S.-T., 1982. “Development of a Laboratory Test to Identify the Scour Potential of Soils at Piles Supporting Offshore Structures,” M.S. thesis, The University of Texas, Austin, Texas, 69 pages. Wang, S.-T., 1986. “Analysis of Drilled Shafts Employed in Earth-Retaining Structures,” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, 1986. Wang, S.-T., and Reese, L. C., 1998. “Design of Piles Foundations in Liquefied Soils,” Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics III, Geotechnical Special Publication No. 75, ASCE, pp. 1331-1343. Weaver, T. J., 2001. “Behavior of Liquefying Sand and CISS Piles During Full-Scale Lateral Load Tests,” Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of California at San Diego. Welch, R. C., and Reese, L. C., 1972. “Laterally Loaded Behavior of Drilled Shafts,” Research Report No. 3-5-65-89, Center for Highway Research, The University of Texas at Austin, May 1972. Yegian, M., and Wright, S. G., 1973. “Lateral Soil Resistance-Displacement Relationships for Pile Foundations in Soft Clays,” Proceedings, 5th Offshore Technology Conference, Vol. II, pp. 663-676. Zhang, L., 2004. Drilled Shafts in Rock, Analysis and Design, Balkema, 383 p. 231 References (This page was intentionally left blank) 232 Name Index Akinmusuru, J. O. ....................................... 4 Duncan, J. M. .......................................... 124 Allen, J. ................................................... 153 Dunnavant, T. W. .............. 62, 63, 64, 74, 87 American Petroleum Institute . 18, 70, 98, 99 Dunnigan, L. P. ......................................... 64 Armitage, H. H. ....................................... 150 Evans, L. T. ............................................. 124 Ashford, S. A. ......................... 105, 107, 108 Fenske, C. W. ............................................ 87 Audibert, J. M. E. ...................................... 87 Fitzgibbon, D. P. ....................................... 54 Awoshika, K. .............................................. 4 Focht, J. A., Jr. .......................... 4, 18, 65, 67 Azzouz, A. S. ............................................ 11 Fong, P. T. ................................................. 87 Baecher, G. B. ............................................. 3 Franke, K. W. .......................................... 108 Baguelin, F. ....................................... 18, 104 Fukuoka, M. .................................... 217, 221 Baligh, M. M. ............................................ 11 Gazioglu, S. M. ......................................... 87 Bhushan, K. ....................................... 87, 104 George, P................................................... 18 Bishop, A. W........................................... 215 Georgiadis, M. ........................................ 154 Bogard, D. ................................................... 4 Gerber, T. M. .......................................... 105 Bowman, E. R. .......................................... 90 Germaine, J. T. .......................................... 11 Briaud, J. L, ............................................... 87 Grime, D. B. ............................................ 104 Broms, B. B............................................... 16 Hales, L. J. ...................................... 107, 108 Brown, D. A. ................... 4, 55, 86, 114, 152 Haley, S. C. ............................................... 87 Brown, E. T. ............................................ 144 Hansen, J. B. ............................................. 59 Bryant, L. M. ............................................... 7 Harder, L. F. .................................... 105, 110 Chameau, J. L. ........................................ 217 Hassiotis, S.............................................. 217 Christian, J. T. ............................................. 3 Hetenyi, A. .......................................... 14, 30 Cox, W. R. .... 52, 53, 54, 62, 63, 74, 92, 126 Hoek, E. .......................... 144, 145, 147, 151 Dapp, S. D. .............................................. 114 Horvath, R. G. ......................................... 135 Darr, K. ..................................................... 59 Hrennikoff, A. ............................................. 4 Davis, E. H. ............................................... 18 Isenhower, W. M..................... 114, 174, 187 Decker, R. S. ............................................. 64 Jamiolkowski, M. ...................................... 18 Det Norske Veritas .................................... 18 Jezequel, J. F. .................................... 18, 104 DiGiola, A. M. .......................................... 16 Johnson, G. W. .......................................... 54 233 Name Index Johnson, R. M. ........................................ 114 Kenney, T. C. .......................................... 135 126, 130, 131, 132, 137, 140, 141, 156, 164, 187 Koch, K. J. .................................................. 4 Ripperger, E. A. .................................. 51, 54 Kooijman, A. P. ........................................ 55 Rojas-Gonzalez, L..................................... 16 Koop, F. D........... 52, 54, 62, 63, 74, 92, 126 Rollins, K. M........................... 105, 107, 108 Kubo, K. .................................................. 167 Rowe, R. K. ............................................. 150 Lane, J. D. ............................................... 105 Schmertmann, J. H. ................................. 132 Lee, L. J................................................... 104 Seed, R. B. ...................................... 105, 110 Liang, R................................................... 144 Sherard, J. L. ............................................. 64 Long, J. H................................ 13, 63, 64, 79 Shields, D. H. .................................... 18, 104 Malek, A. M. ............................................. 11 Simpson, M. ............................................ 152 Marinos, P. ...................................... 145, 151 Skempton, A. W........................................ 65 Matlock, H. ..................................... 108, 109 Smith, T. D................................................ 87 Matlock, H. . 4, 20, 51, 54, 68, 70, 72, 74, 88 Speer, D........................................... 133, 141 McClelland, B. .............................. 18, 65, 67 Stevens, J. B. ............................................. 87 Meyer, B. J. ............................................... 87 Stokoe, K. H. ............................................. 54 Morgenstern, N. R................................... 215 Sullivan, W. R. .......................................... 87 Morrison, C. M. ........................................ 55 Terzaghi, K. ...................... 14, 65, 67, 87, 92 Murchison, J. M. ..................................... 104 Thompson, G. R. ................................. 16, 55 Newman, F. B. .......................................... 16 Timoshenko, S. P. ..................................... 39 Nusairat, J. .............................................. 144 Van Impe, W. F. ...................................... 156 Nyman, K. J. ........................................... 132 Vesić, A. S. ............................................... 54 O’Neill, M. W.4, 62, 63, 64, 74, 87, 104, 139 Wang, S.-T. ..... 29, 59, 63, 64, 105, 108, 187 Oakland, M. W. ....................................... 217 Wood, D. ................................................... 18 Parker, F., Jr. ....................................... 92, 97 Wright, S. G. ....................................... 16, 55 Parsons, R. L. .......................................... 114 Yang, K. .................................................. 144 Poulos, H. G. ............................................. 18 Yegian, M. .......................................... 16, 55 Price, V. E. .............................................. 215 Zhang, L. ................................................. 147 Welch, R. C. .................................. 63, 82, 84 Reese, L. C.4, 18, 52, 53, 54, 55, 59, 62, 63, 74, 82, 84, 87, 88, 92, 97, 105, 108, 123, 234