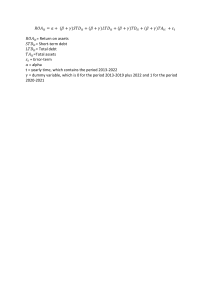

Reparations Aff

The University of Texas occupies land stolen from the Tonkawa, Comanche, and

Apache peoples. This school is hardly unique. Built by black slaves on land stolen

through genocidal wars of conquest, the primary goal of colleges is national capital

accumulation and maintaining racial stratification. Universities proliferate colonial

violence by inculcating nationalism and directly promoting the expansion of the global

economy at the expense of the dispossessed and the ecological balance of our planet.

These institutions owe a debt to the millions of dead bodies they have left in their

wake

Stein 22 - Sharon Stein, In the book Unsettling the University in 2022 “Unsettling the

University Confronting the Colonial Foundations of US Higher Education”

[https://www.press.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/media/2022/10/Unsettling_the_University_Intro_and_C

h1.pdf] Accessed 11/17/23 SAO

American colleges were not innocent or passive beneficiaries of conquest and colonial slavery. The European invasion

of the Americas and the modern slave trade pulled peoples throughout the Atlantic world into each others’ lives, and colleges were among the colonial institutions that braided their histories and rendered their fates dependent

and antagonistic. —Craig Steven Wilder, 2013, p. 11 On September 18, 2019, New Mexico announced plans to offer free public higher education for all state residents, funded largely by increased revenue from oil production in the

state. Just a day earlier, the University of California announced that it would divest its endowment funds of fossil fuel stocks. In an op-ed piece for the Los Angeles Times, the university’s chief investment officer–treasurer and

chairman of the board of regents’ investments committee noted, “The reason we sold some $150 million in fossil fuel assets from our endowment was the reason we sell other assets: They posed a long-term risk to generating

strong returns for UC’s diversified portfolios. . . . We have chosen to invest for a better planet, and reap the financial rewards for UC, rather than simply divest for a headline” (Baccher & Sherman, 2019). Viewed together, these two

announcements offer a glimpse into the possible futures for public higher education that are deemed imaginable and desirable in what is currently known as the United States. In one case, a state planned to boost public funding

through profits made from the extraction and sale of fossil fuels (a plan that ultimately fell through), while in the other, one of the country’s largest public university systems justified its divestment from fossil fuels out of concern

for future profits. Beyond illustrating some of the contradictions and convergences that circulate within current popular horizons of hope about the future of US higher education, when viewed from a decolonial perspective, these

two announcements expose the ethical and ecological limits of these horizons. Throughout this book, I use “decolonial” to refer to analyses and practices that (1) critique ways of knowing, being, and relating that are premised on

systemic and ongoing colonial violence, and that (2) gesture toward possible futures in which these colonial patterns of knowledge, existence, and relationship are interrupted and redressed. I describe my approach to decolonial

public higher education is predicated on the continuity of a

political economic system that requires endless growth, extraction, and consumption and that can

therefore hold little regard for its negative impacts on the human and other-than-human beings who

pay the price for this expansion. In this way, both of these proposed funding models reproduce the colonial architectures

of accumulation that form the foundations of US higher education. I use the phrase “colonial foundations of US higher education” to point to the

critique further in chapter 1. Despite their differences, in both announcements the future of

fact that while entrenched patterns of institutional violence do have specific starting points, they are not relegated to the past. Rather, they have continued to shape all subsequent higher education developments—never in a

different higher education futures will not be possible if we do not first

untangle and reckon with these historical and ongoing colonial foundations. I trace the origins of these foundations, consider how the

deterministic way but nonetheless in a way that suggests

harms of colonization and slavery continue to seep through these foundations into the present, and question the structural integrity of a future that rests on these foundations, especially if we fail to confront their disavowed costs

for people and the planet. Situating This Book’s Intervention Scholars have addressed the immense contemporary challenges of US higher education from numerous theoretical and methodological perspectives. Yet across these

dif­ferent perspectives one finds a common rhetorical strategy (echoed in the popular media) that compares the current state of higher education to an idealized higher education past and uses that past as a guide for imagining an

idealized higher education future. There is an alternative means of engaging with contemporary US higher education that problematizes the naively hopeful narratives of US higher education futurity that presume seamless

continuity and progress, as well as the selectively nostalgic narratives of US higher education history that invisibilize (make absent) colleges’ and universities’ structural complicity in racial, colonial, and ecological violence. In doing

so, this book intervenes in what are by now fairly prolific and increasingly mainstream conversations across the fields of critical university studies and higher education studies about the privatization and marketization of higher

education. The book engages this literature but also stretches it by bringing a decolonial lens to the fore using a historiographic method of analysis.

By examining the colonial foundations of US higher education

with a view to their implications for the present and future, I suggest that contemporary forms of academic capitalism in the neoliberal university should be seen not as entirely novel but as rooted in a long-standing architecture of

dispossession and accumulation that has formed the template for US higher education from the very beginning. Although this book does not address in great detail pressing contemporary challenges, such as surging

student debt, precarious academic labor, and contentious questions about increasingly diverse campuses and curriculum reform, it suggests that if we engage these issues with the

underlying colonial template of US higher education in mind, we are likely to arrive at very dif­ferent

conclusions about both the root causes of these problems and ethical modes of responding to them In this sense, Unsettling the

University resonates with the work of a small but growing number of scholars and activists who have drawn attention to how US colleges and universities have been consistently implicated in the reproduction and naturalization of

social and ecological harm, particularly by serving as “an arm of the settler state—a site where the logics of elimination, capital accumulation, and dispossession are reconstituted” (Grande, 2018, p. 47 [emphasis in original]; see

also Andreotti et al., 2015; Boggs et al., 2019; Boggs & Mitchell, 2018; Boidin, Cohen, & Grosfoguel, 2012; Chatterjee & Maira, 2014; Daigle, 2019; Hailu & Tachine, 2021; S. Hunt, 2014; La Paperson, 2017; Meyerhoff, 2019;

Minthorn & Nelson, 2018; Minthorn & Shotton, 2018; Patel, 2021; Rodríguez, 2012; StewartAmbo & Yang, 2021; Wilder, 2013). Many of these scholars are situated not in higher education studies or critical university studies but

rather in Black, Indigenous, or other critical ethnic studies, women and gender studies, and related interdisciplinary fields (Stein, 2021), some of them organized under the heading of abolitionist university studies (Boggs et al.,

2019). Despite their internal diversity, these critiques share a diagnosis that the fundamental harm inflicted by US higher education institutions is not only that they exclude historically and systemically marginalized communities

but also that they were founded and continue to operate at the expense of those communities. Drawing on this basic decolonial insight, this book offers an invitation to rethink inherited assumptions about the relationship

To pluralize possible higher

education futures requires first interrupting the hegemony of the currently dominant vision for the

future, which is rooted in three primary promises: (1) that higher education should exemplify and enable

continuous progress within its own walls and society at large; (2) that higher education is, in its truest

between the past and the present of US higher education so that we might pluralize the available imaginaries for the future (Barnett, 2012, 2014; Stein, 2019).

form, a benevolent public good; and (3) that a primary purpose of higher education is to enable

socioeconomic mobility. These promises, which I unpack in more detail in chapter 1 and illustrate throughout this volume, shape the terms of both scholarly and popular conversations about higher

education, including the questions that we ask about the predicament we currently face and, thus, the responses we are able to imagine and desire. These promises have such a hold on

the collective imagination about higher education that nearly all of the available theories, frames,

grammars, and vocabularies for thinking about or enacting justice and change in higher education fail or

falter when confronted with decolonial analyses that challenge their orienting assumptions and

investments. As a result, many people—including scholars, administrators, students, staff, and the public as a whole—lack a frame of reference for substantively engaging with decolonial critiques and considering

their implications for research, teaching, and practice in higher education. Further, even once people start to see the value of these critiques, they often decontextualize them, selectively extract from them, or graft them back into

mainstream frames and practices in ways, whether intentional or not, that align with and therefore do not interrupt existing individual advantages and institutional agendas (Ahenakew, 2016; Spivak, 1988; Tuck & Yang, 2012).

Thus, one reason that decolonial critiques are often misunderstood or misused in higher education contexts is that preexisting intellectual scaffolding is not in place that would support rigorous, reflexive decolonial inquiry. But

another reason is that

many of us lack the capacities to hold space for the affective difficulties and discomforts inevitably involved in facing the depth, complexity, and magnitude of problems that have no immediate, feel-

good solutions. Such difficulties and discomforts are further amplified when decolonial critiques ask us to question our investments in the benevolence and futurity of the institutions that helped to create these problems in the first

place and, further, to accept responsibility for our own role in reproducing those problems. To confront these difficulties and discomforts in generative ways would require us to go beyond mere critique in order to develop stamina

for the difficult, long-term work of confronting the violence that underwrites modern institutions of higher education, the study of higher education itself, and thus our livelihoods as scholars, practitioners, and students. It would

also require us to develop capacities for redressing and repairing these violences within the contemporary context of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. This, in turn, has significant political and economic

implications, as it would require those who currently benefit from systemic injustice to give up their accumulated power and wealth. Mobilizing these kinds of decolonial changes at both individual and institutional levels is beyond

what can be accomplished in this or any scholarly text, especially because it requires more than just intellectual work; however, I gesture toward some possible pathways forward. While there remains a serious question as to

whether higher education institutions can “right the wrongs that brought them into being” (Belcourt, 2018), this book is primarily intended for those who are most invested in the promises offered by US colleges and universities,

which tend to be those of us who work and study within them. However, the aim here is not to convince people to adopt or embrace decolonial critiques of higher education. Instead, I invite those concerned about the current

state and future of US higher education to “pause” (Patel, 2015) long enough to open themselves up to being surprised and unsettled by what decolonial critiques might teach us—including insight into the underlying costs of the

promises our institutions offer. This will require interrupting the temptation to selectively “consume” decolonial critiques in ways that circularly affirm existing colonial assumptions, investments, and desires, in particular desires for

virtue, purity, progress, and futurity ( Jimmy, Andreotti, & Stein in Ahenakew, 2019; Shotwell, 2016; Stein et al., 2020; Tuck & Yang, 2012). The book therefore offers no simplistic, universal, or feel-good solutions but rather

emphasizes the challenges, complexities, conflicts, failures, and contradictions involved in trying to interrupt colonial patterns. Although decolonial critiques offer no universal prescription for action, they can make it more difficult

to avoid what many of us would rather not see and would prefer to turn our backs to. Facing this reality is vital in a time when it is increasingly difficult to ignore calls to reckon with the ongoing colonial legacies of our campuses.

Thus, whether or not they ultimately agree with the

decolonial critiques that orient this book, those who accept the invitation to pause might find that it enables them to ask previously unthinkable

questions about the past, present, and future of US higher education, and about our subsequent responsibilities as scholars, practitioners, and students, without immediately demanding solutions or seeking absolution. Addressing

it seeks

to interrogate the socially sanctioned ignorance (Spivak, 1988) about higher education’s colonial foundations, so

that we might identify and interrupt the reproduction of colonial logics and practices in the present. To do

Unthought Questions This book seeks to make tangible what remains largely “unthought” (Hartman & Wilderson, 2003) in both scholarly and mainstream conversations about US higher education. In particular,

this, the book offers a thorough examination of what Kevin Bruyneel (2017) calls “settler memory” in narratives about US higher education. As Bruyneel notes, “When we fight about the meaning of the past, we are not fighting

Settler

memory refuses to attend to the implications of colonization in the present, even when evidence of

those implications is readily available. I suggest that collective investment in the continuity of the shiny promises offered by US higher education, as well as collective disavowal of the

over history, we are fighting over memory, specifically the collective memories that purport to bind and define a people’s sense of who they are from past to present and on into the future” (p. 36).

role of racial, colonial, and ecological violence in enabling those promises, shapes the settler memory that contributes to the reproduction of higher education’s romantic foundational myths and organizational sagas (Clark, 1972;

Meyerhoff, 2019). Approaching the foundations of US higher education from a decolonial angle challenges the common framing through which people resist (admittedly troubling) contemporary institutional economic formations

and imperatives by pining for a return to “better days.” As Abigail Boggs and Nick Mitchell (2018) note, this romanticism about the past “repeats the forgetting of the dispossession at the university’s origins while simultaneously

drumming up a sense of crisis regarding the potential consequences of its downfall” (p. 441; see also Boggs et al., 2019; Stein & Andreotti, 2017). In contrast to this wilful ignorance about the past and the ways it shapes the

How might the terms of current academic and political debates change if

the responsibilities of that very real lived condition of colonialism were prioritized as a condition of

possibility?” (p. xx [emphasis added]). I supplement this question with another, which is implied by Byrd’s but is nonetheless worth articulating, given the risk that critiques of colonialism will become anthropocentric

present, I invite readers to take up Jodi Byrd’s (2011) question “

and overlook the effects of colonization on other-than-human beings. That is: How might the terms of current academic and political debates change if we also prioritized our reciprocal responsibilities to the earth as a living entity,

rather than as a property or resource that can be commodified, owned, and even “made sustainable” for continued extractive purposes? In bringing these two questions together, I am drawing on the work of decolonial, especially

Indigenous, scholars and activists who have for a long time drawn connections between colonialism, capitalism, and climate change (Davis & Todd, 2017; Whyte, 2020). These connections point to the close relationship between (1)

the systemic, historical, and ongoing racialcolonial violence that enables the US socioeconomic system and the comforts and securities it promises its citizens (especially white citizens) and (2) the inherent ecological

unsustainability of a socioeconomic system that is premised on infinite extraction, growth, and accumulation, given that we inhabit a finite planet. This book seeks to integrate these two, often-siloed concerns, and consider their

combined implications for higher education.

Student loans are explicitly anti-black

Mustaffa & Dawson 21 - JALIL B. MUSTAFFA, Villanova University & CALEB DAWSON,

UC Berkeley, in the Journal Teachers College Record, June 1st, 2021 “Racial Capitalism and

the Black Student Loan Debt Crisis”

[https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/016146812112300601] Accessed 10/26/23 SAO {we

defend all debt forgiveness, not just student loans]

Student loans reflect a larger shift in U.S.

society in which people are forced to go into debt for basic needs. This paper uses racial capitalism to account for how Black educational desires are

co-opted, the government configures inclusion according to predatory terms, and the student loan industry forms a debt trap. Student loans as a policy rely on anti-Black

racial logics and systemic forces. Through financialization, student loans convert educationally aspirant people into

units of investment (as opposed to units of labor). The majority of Black people who enroll in higher education never secure the promise of college as always “worth-it,” yet the arrangement continues to be

worthwhile for student loan profiteers (C. H. F. Davis et al., 2020). This is why student loans are perfect for racial capitalism—they answer demands

Racial capitalism is offered as a theory to understand student loans within the long history of racialized debt and higher education.

for social access and inclusion (which are already reduced to mean credentialism)—and reproduce both the disposability and

dispossession of Blackness. Again, racial capitalism does not always make cents as in making a profit, but it

does always make sense as in ensuring a group is exploitable now or in the future. Lastly, while the purpose of this paper was to

trace how student loans operate as a tool in racial capitalism to uniquely exploit Black borrowers, this analysis still falls short. That is to say, this paper only contributes to one part of a racial justice praxis: providing a lens to

understand the problem. There is a need for scholarship and activism that explores how to eliminate student loan debt in a way that makes all racialized debt unthinkable. In other words, a racial justice praxis cannot just target

crises of racial capitalism—student debt—but must also abolish the racist logics, processes, and policies that make the crisis and Black precarity possible in the first place (Robinson, 2000). To begin, scholars must contextualize

racialized debt in higher education with other debt traps like housing, healthcare, or credit cards. Debt elimination should not happen solely for student loans; such an approach wrongly reifies education as the only social policy

There are activist movements and advocacy-driven scholarship

growing to argue for full debt cancelation coupled with free college as a gateway to a larger vision to imagine livelihoods beyond debt (Mir & Toor, 2021). As is often the case,

reckonings with anti-Blackness—where debt is one such tool—are made possible by grassroots

mobilizations (Dawson, 2021). There is the Debt Collective (2020), which launched student loan debt strikes where borrowers refused to participate in repayment in order to highlight the exploitation of student

(Kantor & Lowe, 2006) and the Black student debt crisis as an aberration of capitalism.

loans. The Collective successfully negotiated the cancellation of over $1 billion of student loan debt and forced the Department of Education to strengthen protection efforts for student borrowers (Appel, 2019). While also

proponents of full student debt cancellation, The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) (online) has prioritized criminal legal debt as a primary issue and has successfully launched bail mutual aid funds to help secure Black people’s

release from prison. In addition, M4BL has pushed cities closer to abolishing cash bail and reducing fees in places like Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Ferguson, and Chicago. Next, Cooperation Jackson (online) is building a model whose

“basic theory of change is centered on the position that organizing and empowering the structurally under and unemployed sectors of the working class, particularly from Black and Latino communities, to build worker organized

and owned cooperatives will be a catalyst for the democratization of our economy and society overall.” All three coalitions are organizing for forms of debt cancellation and helped bring the solution to the national stage. Arguably,

their longterm organizing, while often outside the institutional system, opened up the space for debt cancellation to be a legitimate solution in higher education research and policy debates. In just the last three years, there have

been several research reports on student debt cancellation, public letters from hundreds of policy advocacy organizations supporting broad cancellation, and legislation like the College for All bill to cancel all student debt (Debt

Collective, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, interest on federally held student loans was cancelled, and though described publicly as a payment pause, the interest during the pause will never be added onto the loan. Many

the executive branch, because of authority granted to the Secretary of Education in the

original Higher Education Act, has the power to cancel student debt in any amount and anytime (Student Borrower

Protection Center (SBPC), 2020). The COVID-19 pause and cancellation of student debt interest, implemented originally by executive order, is evidence of this authority. Cancellation can abolish

the racial student debt trap that targets Black people and harms many groups as collateral damage. While

advocates argue that

calls to dismantle student debt and racialized debt in general are growing (Mir & Toor, 2021; SBPC, 2020; Taylor, 2019), movement building continues to be necessary to generate political will. Disrupting racial capitalism demands

the cancellation of student loans. However, what that victory and others will mean for Black people and other marginalized groups will depend on a critique of racial capitalism that uproots racial logics and systems—from

meritocracy and credentialism to predation and financialization.

The draft was never abolished. The US government strategically dangles opportunities

for social mobility in front of minorities to fuel its imperial wars abroad.

Zhang 22 - Sharon Zhang, Truthout, September 20, 2022 “GOP: Student Loan Forgiveness

Hurts Anility to Lure Poor People Into Military” [https://truthout.org/articles/gop-student-loanforgiveness-hurts-ability-to-lure-poor-people-into-military/] ahs//jw accessed 10/26/2023

Republicans are

complaining that President Joe Biden’s student debt cancellation program will

hurt the Pentagon’s ability to recruit poor people into the military.

facing criticism for

Last week, a group of 19 Republican representatives sent a letter saying that Biden’s recent plan to

cancel up to $10,000 for borrowers or $20,000 for Pell Grant recipients making under $75,000 a year is “removing any leverage the Department of Defense” to recruit people wishing to access higher education but who can’t afford it. Rep. Don Bacon (R-Nebraska) tweeted a link to a news

report on the letter, saying that he is “very concerned that the deeply flawed and unfair policy of blanket student loan forgiveness will also weaken our most powerful recruiting tool at the precise moment we are experiencing a crisis in military recruiting.” Bacon faced ridicule for his

lawmakers are openly admitting that they

keeping higher

education expensive as a tool for military recruitment.

folks want poor people to be put in a

corner so they will go fight endless wars that benefit the rich just to receive an education

known as the

“poverty draft.” The military’s offers financial incentives like student loan repayment,

for young people experiencing debt or poverty.

the military often actively travels to schools in

poor and nonwhite neighborhoods in order to recruit

Black, Latinx, Indigenous and low-income

people are disproportionately placed in the most dangerous situations compared to other enlistees.

people shouldn’t have to put their

lives on the line just in order to afford higher education.

if canceling student debt actually does decrease military

recruitment, that would be a good thing.

canceling student debt

would hamper U.S. imperial/colonial efforts.”

tweet by progressives like former Ohio state senator Nina Turner, who are saying that GOP

have an interest in

“Read between the lines: these

,” Turner wrote. Republicans have faced

criticism for similar statements. Last month, Rep. Jim Banks (R-Indiana) similarly complained that student debt forgiveness “undermines one of our military’s greatest recruitment tools.” Critics of the Pentagon have long condemned what is

of

free college, and other cash incentives are a draw

And, knowing this,

; then, once they join,

This

predatory practice is unethical for many reasons, critics of the practice argue. People in active military service are at high risk of mental health issues like suicide, and critics say that poor

and

bodies

With that in mind, critics said on social media that it is alarming that Republicans would not only acknowledge this fact but also

openly advocate for it, saying that Republicans were saying “the quiet part out loud.” Activist group the Debt Collective wrote that

, in fact,

wrote on Twitter. “It is not a stretch to say that

“One of the best parts about canceling student debt is thinking of all the people who no longer feel compelled to enlist in the military to pay off their loans,” the group

— and making college free —

You have a categorical imperative to reject doctrines that uphold cultural otherization

Dunford 17 - Robin Dunford, University of Brighton, Journal of Global Ethics,

September 21st 2017 “Toward a decolonial global ethics”

[https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17449626.2017.1373140] Accessed 10/1/20 SAO

Decolonial ethics is not without its tensions, some of which I explore in this section. In principle, the above two aspects of pluriversality cut in different directions. The pluriversal as that which is formed through inter-cultural

dialogue points in the direction of a dialogue in which positions are not excluded in advance (even if this dialogue may take place, initially at least, only amongst the oppressed), and in which no particular standard or value is valid

in advance of dialogue.7 Taken alone, this form of pluriversality raises questions. Does inter-cultural dialogue have any limits or constraints? Are values justified solely by virtue of having emerged through inter-cultural dialogue, or

Are any and all views allowed to the table, or ought certain

views be rejected? What about those views that reproduce colonial narratives or values that have done

so much to silence, undermine and oppress those on the underside of the colonial matrix of power? Taken

is it possible for a value to be wrong, normatively speaking, despite emerging from this process?

alone, this aspect of pluriversality cannot provide an account of whether there are views, practices and modes of engagement that should not be allowed in discussion. Nor can it rule out, as illegitimate, views, values, practices or

. Pluriversality as a value suggests that practices, worldviews, values or

policies are legitimate only if they remain compatible with the existence of other worlds. In this sense, pluriversality sets a standard of legitimacy that would judge as

morally wrong any worldview, value or practice that does not accept the existence of, or that works to shut down,

other worlds. That is not necessarily to say, though, that those holding such views ought to be excluded from dialogue. There is a tension, then, between the two aspects of pluriversality. Giving ultimate priority to

policies that, despite emerging from discussion, may nonetheless go on to oppress others. It is here that pluriversality as a value enters

one aspect cannot solve this tension. Without any reflection on its emergence from pluriversal dialogue, the substantive value of pluriversality would become a new abstract, already-universal design and would undermine all

Without the substantive value, there is no way of identifying why a dialogue that takes seriously

multiple cosmovisions is a morally good thing. Nor would there be any way of casting any judgment on or identifying as morally wrong certain visions – racist visions, sexist

visions, visions that advocate a form of modernity that inevitably reproduces coloniality. Both aspects of pluriversality must

commitment to taking seriously as producers of knowledge those that are marginalised.

remain, and decolonial global ethics must find ways of navigating (if not resolving) any tension between them. It will be for pluriversal dialogue to find ways of navigating this potentially irresolvable tension. To offer some ideas to

the substantive value of pluriversality has emerged, in practice, through pluriversal exchanges in

indigenous, peasant (Martínez-Torres and Rosset 2014), feminist (Leinius 2014) and World Social Forum praxis (Conway and Singh 2011). Having

emerged as an abstract value through concrete, inter-cultural dialogue, it can, in turn, retrospectively

account for why it is that such dialogue is, normatively speaking, a good thing. One might also note that the abstract value of a world in

any such discussion, it is worth noting that

which other worlds are possible does not give rise immediately to concrete values, practices, policies and attitudes. Understanding what kind of practices, policies and modes of behaving and living enable other worlds to exist, and

fostering the kind of respect for other worlds that such practices and ways of living may require, requires pluriversal dialogue, for it is through such exchanges that it will become apparent that certain demands and ways of living

can and do result in the oppression of others. Both aspects of pluriversality can thus be mutually enriching in practice, despite the potential for tension between them. Whilst there is not room to introduce them in depth here,

any readers inclined to think that this tension makes decolonial ethics unworkable, hopelessly idealistic

and of no use in the ‘real world’ would be advised to explore the practices of the social movements that

navigate these tensions. Related to this difference between the two aspects of pluriversality are tensions between decoloniality as an option and decoloniality as an imperative. For Mignolo, there will

be no place for one option to pretend to be the option. The decolonial option is not aiming to be the one. It is just an option that, beyond asserting itself as such, makes clear that all the rest are also options. (2011, 21) Similarly,

what we put on the table is an option to be embraced by all those who find in the option(s) a response to his or her concern and who will actively engage, politically and epistemically, to advance projects of epistemic and

subjective decolonisation and in building communal futures. (2011, xxvii) This weaker version of decoloniality appears not to rule out, as incompatible with decolonial global ethics, other visions. ‘Western civilization’ would then,

Mignolo (2011, 176) suggests, ‘merely be one among many options, and not the one guide to rule the many.’ The decolonial option serves to add another option to the table. It does not necessarily reject Western modernity, liberal

cosmopolitanism or other positions, provided that they, too, present themselves only as an option. When understanding pluriversality in terms of its procedural aspect, this makes perfect sense. It would be wrong to set out, in

The worry with this weaker version, however, is that it risks ‘losing the ability for

critique’ (Alcoff 2012, 6) and becoming a relativism of anything goes. For Grosfoguel (2012, 101), by contrast, pluriversality is not

‘a relativism of anything goes’. Similarly, for Dussel (2012, 19), a decolonial perspective does ‘not presuppose the illusion of a non-existent symmetry between cultures’. Instead, it

acknowledges that some cultures, cosmovisions and livelihoods are systematically threatened by others

and cannot survive in the face of cosmovisions and lifestyles that are inextricably tied to the ceaseless

extraction of resources, the dispossession of people and poor working conditions. These perspectives follow when the substantive

value of pluriversality is invoked. If the practices, institutions and lifestyles that we associate with modernity continue to

depend upon and be constituted by coloniality, then these are not compatible with a world in which

other worlds fit. It is for this reason that Dussel suggests that decolonial liberation is ‘impossible for capitalism’ and must not accept the colonial matrix of power ‘as a whole’ (Dussel 2013, 138). Though Mignolo

advance, one option as an imperative, as one we ought to follow, albeit in different ways.

primarily presents decoloniality as an option, at other times he suggests that ‘pluriversal futures … are only possible if the reign of economic capitalism ends’, on the basis that economic capitalism provides space only for practices

that can be turned into, or do not obstruct, profits, and hence does not allow different worlds to exist on equal terms (Mignolo 2011, 292). This article is not the place to analyse the validity of Mignolo and Dussel’s accounts of

decoloniality should be considered an imperative, and not just an option to be placed on the table. So

understood, decolonial global ethics goes beyond a relativism of anything goes. Any option that inevitably depends upon

the systematic destruction of other words would violate the principle of a world in which many worlds

fit. Decoloniality, and its central value – pluriversality – invoke stringent demands that rule out a number of worlds, practices and lifestyles. It identifies as wrong a world of economic capitalism if and insofar as it inevitably

capitalism. The point is to suggest that

depends on, and cannot be reformed to prevent, the destruction of other worlds. It identifies as wrong practices of resource extraction, if and insofar as they destroy the livelihoods of peasant and indigenous peoples. It identifies

as wrong highly polluting lifestyles, if and insofar as they lead to the destruction of the lives and cosmovisions of those who are dispossessed and displaced as a result of environmental change.

It means, finally,

that Western civilization as we know it cannot be one legitimate option among many if and insofar as

it is constituted through, and cannot be separated from, coloniality. If decolonial global ethics is to unpick the colonial matrix of power and

liberate people (s) from domination, it must be an imperative. It must be understood, as it is by Mignolo (2011, 23) in one of his stronger statements, as a project ‘which all contending options would have to accept’. This

does not mean that decoloniality and pluriversality offer a singular and rigid global design. A pluriversal world is one

in which multiple options are possible – a world in which many worlds can co-exist. Whilst other options would be circumscribed insofar as they would have to accept the decolonial imperative of working towards a pluriversal

world, this still leaves room for many options, many possible lives, livelihoods and cosmovisions.

Only those worlds that involve, inextricably, the continued

domination of others are judged as wrong (though it may well be the case that such views should not be excluded from dialogue, given that dialogue itself may help enrich the kind

of mutual respect that would lead to the abandonment of such views). Far from invoking a relativism of anything goes, this principle is a

demanding one, with radical implications for global social structures and ways of living. The building of a pluriverse is and

must be an open-ended project, fed by dialogues amongst actors from across the world. Moreover, the demand of a pluriverse may be impossible to meet fully; in an

interconnected world, it may be impossible to ensure that it is not the case that the actions of some constrain the worlds of others. This does not mean, however, that some worlds,

practices, livelihoods, lifestyles and institutional designs are not more compatible with a pluriverse than others. Recognising interconnectedness – and the long history of

interconnectedness – only increases the importance of striving for a pluriversal world in an attempt to build a world free from the domination and destruction of the colonial matrix of power. Decolonial theory makes a distinctive

decolonial theory offers

a fundamentally global ethics that is distinct from individualistic and universalistic cosmopolitan theory. It begins with those

and valuable contribution to global ethics. It begins with an analysis of coloniality as the inextricable darker side of modernity. In reflecting on what it would mean to decolonise,

perspectives threatened by a colonial matrix of power, and proposes inter-cultural dialogue across diverse cosmovisions. In so doing, it refuses to specify, in advance, what is of fundamental moral significance. Finally, it embraces

A value is pluriversal if, rather than being set up as an abstract and

already-universal value, it is constructed through dialogue across multiple cosmovisions. Pluriversality also refers to a value

of a world in which many words fit. Pluriversality thus offers an account of both a global process through which global values can legitimately be formed, and a value that can be

used to judge particular practices, policies, processes or social structures. Pluriversality as a value is demanding and judges as morally wrong

practices and social structures that inevitably dispossess others. But it is not equivalent to those universal, global designs central to the colonial

matrix of power. It is not equivalent, in part, because it embraces radical difference and seeks to multiply options,

rather than close them down. It also differs in that it has emerged from, and can only be fleshed out through, a process of pluriversal exchange. Decolonial theory has been constructed alongside

pluriversality. Plurversality refers, on the one hand, to a way of constructing values.

and through social movement practice. The above presentation of the value of pluriversality, and of the distinctive features of decolonial theory more broadly, has only been possible in light of the work of peasant, indigenous,

feminist and World Social Forum activists contesting various aspects of the colonial matrix of power. Taking decolonial global ethics seriously opens avenues for further work judging whether, how, and why given practices, policies,

processes and structures are compatible with pluriversality in both senses of the term. If this article encourages global ethicists to explore further these questions, then it would have played its small part in contributing to the

construction of an ethical framework that can take seriously and challenge the legacy of colonial rule.

Reject negative arguments based on evaluating consequences of loan forgiveness, 6

warrants.

[1] Infinitely Cascading Consequences: It’s impossible to determine when the

consequences of an action have ended so we can never calculate ethicality

[2] Act-omission distinction: There are an infinite number of things you aren’t doing at

any given time which removes any reason to be moral because people cannot control

what they are being punished for

[3] Probability: We know that student loans are a racially targeted structure, that

means voting aff guarantees the removal of a racist structure. Any future harms are

speculative at best.

[4] Oppression Olympics: Evaluating consequences requires comparing the oppression

experienced by various groups. If we win that a structure is intrinsically racist we

shouldn’t be forced to devalue the oppression that other people experience by

comparing it to future oppression.

[5] Intrinsic Wrongness: Their interpretation would force debaters to defend that

slavery and genocide are morally obligatory if they prevented extinction. This

encourages students to practice dehumanization techniques that spill out of debate.

[6] Political consequences are empirically impossible to predict.

Menand 5 - Louis Menand, Professor at Harvard University, The New Yorker 2005

“Everybody’s An Expert” [http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/12/05/everybodys-an-expert] SS

“Expert Political Judgment” is not a work of media criticism. Tetlock is a psychologist—he teaches at Berkeley—and his conclusions are based on a long-term study that he began twenty

years ago. He picked two hundred and eighty-four people who made their living “commenting or offering advice on

political and economic trends,” and he started asking them to assess the probability that various things would or would not come to pass, both in the areas of the world in which they specialized

and in areas about which they were not expert. Would there be a nonviolent end to apartheid in South Africa? Would Gorbachev be ousted in a coup? Would the United States go to war in the Persian Gulf? Would Canada

the experts had made 82,361

forecasts. Tetlock also asked questions designed to determine how they reached their judgments, how they reacted when their predictions proved to be wrong, how they evaluated new information that did not support

disintegrate? (Many experts believed that it would, on the ground that Quebec would succeed in seceding.) And so on. By the end of the study, in 2003,

their views, and how they assessed the probability that rival theories and predictions were accurate. Tetlock got a statistical handle on his task by putting most of the forecasting questions into a “three possible futures” form.

The respondents were asked to rate the probability of three alternative outcomes: the persistence of the status quo,

more of something (political freedom, [e.g.] economic growth), or less of something (repression, [e.g.] recession). And he measured his

experts on two dimensions: how good they were at guessing probabilities (did all the things they said had an x per cent chance of happening happen x per cent of the time?), and how accurate they were at predicting specific

the experts performed worse than they would have if they had simply assigned an equal

probability to all three outcomes—if they had given each possible future a thirty-three-per-cent chance of occurring. Human beings who spend their lives studying the state

of the world, in other words, are poorer forecasters than dart-throwing monkeys, who would have distributed their picks evenly over the three choices.

outcomes. The results were unimpressive. On the first scale,

Even if consequences matter, debt forgiveness works

Akhtar & Hoffower 20 - Allana Akhtar, senior health reporter for Insider, and Hillary

Hoffower, Economics Correspondent, Business Insider, June 10th 2020 “9 startling facts

that show just how hard the student-debt crisis is hurting Black Americans”

[https://www.businessinsider.com/how-americas-student-debt-crisis-impacts-black-students-2019-7]

Accessed 12/1/23 SAO *brackets in original

Education is one area where Black

Americans are hurting the most as the result of institutionalized racism — especiallywith student loans.

In the wake of George Floyd's death, the Black Lives Matter protests have shined a spotlight on America's long history of inequality and systemic racism.

Black students are not only more likely to need to take on debtfor school, graduates are also nearly five times as likely to default on their loans than their white peers. The racial gap between Black and white student borrowers

prompted senators who ran for a presidential bid in 2019 to address the issue during their campaigns: Elizabeth Warren's initiative would have wiped all student debt for 75% of US borrowers, and Bernie Sanders called to eliminate

all such debt. Here are nine mind-blowing statistics about the student-debt crisis' impact on black borrowers as compared to white students. (The majority of data sources compared Black- and white-borrower debt, which is why

other racial groups were not mentioned directly.) 1. 86.6% of black students borrow federal loans to attend four-year colleges, compared to 59.9% of white students.Of the black students who graduated in 2003, one in two

defaulted on their student loans sometime within the following 12 years, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics as analyzed by Student Loan Hero. In comparison, the rates of default for white student

was at 21.5%, and 36.1% for Latino students. 2. Even well-off black students carry more student-loan debt. Beth Akers, fellow at the Brookings Institution's Center on Children and Families, told Martha C. White of NBC News that

black students don't benefit as much from their parents' wealth as white students do. Well-off black families have a lower average net worth than white families, and they hold their wealth differently — mostly in homeownership

as opposed to financial assets like stocks that are easy to access, White reported. 3.An average black graduate has $7,400 more in student debt than his or her white peer. Black students with bachelor's degrees owe $7,400 more

student debt on average upon graduation than white grads, according to Brookings. The gap widens over time: after four years, black grads hold almost twice as much in student debt as their white counterparts at $53,000.

Brookings analyzed restricted-use data from the Department of Education's Baccalaureate and Beyond surveys, as well as Department of Education and Census Bureau data. 4. Black student-loan borrowers default on their loans at

five times the rate of white graduates. Though just six out of every 100 BA holders default on their loans, black borrowers are much more likely to default: 21% of them default on their loans compared to just 4% of white grads,

according to Brookings. Furthermore, black graduates with a bachelor's degree are even slightly more likely to default — or don't make a payment for 270 consecutive days — than white college dropouts. Brookings does not

attribute the racial disparity to just lower levels of parent education or family income. Instead, they point to higher for-profit graduate-school enrollment and lower earnings post-grad. 5. Graduates of historically black colleges and

universities (HBCUs) take on 32% more debt than their peers at other colleges. Howard University Students HBCU Students of Howard University march from campus to the Lincoln Memorial to participate in the Realize the Dream

Rally for the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington August 24, 2013. REUTERS/James Lawler Duggan A Wall Street Journal analysis of Education Department data found that not only do alumni at HBCUs take on 32% more

debt than graduates at other public or nonprofit four-year schools, the majority of graduates haven't paid any debt in the first few years out of school. While HBCUs make up just 5% of four-year American colleges, they make up

"50% of the 100 schools with the lowest three-year student-loan repayment rates," the Journal found. The discrepancy could be because black families already have less wealth compared to other racial groups. HBCUs are typically

more affordable than other institutions, according to Student Loan Hero. Spelman College, the most expensive HBCU as of January 2019, costs $28,181 in tuition, several thousand dollars less than the national average of $32,410

Eliminating student-loan debt would narrow the racial wealth gap for young families. The

Roosevelt Institute, a liberal think tank based in New York, found that white households headed by people between the ages of 25 and 40 have 12 times the amount of

wealth on average than [of] black households. By eliminating student debt — as presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have proposed to do in some

capacity — the ratio shrinks [it] to just five times the amount of wealth. Even after canceling debt, however, the racial wealth gap will remain high: the median

for private four-year colleges. 6.

wealth in young white households would total $52,700, compared to $10,010 for their black peers. 7. White borrowers pay down their education debt at a rate of 10% a year, compared with 4% for black borrowers. college

graduate worried surprised Chip Somodevilla/Getty That's according to a study by Jason Houle and Fenaba Addo in SAGE journals. They found that racial inequalities in student debt contribute to the black-white wealth gap in early

adulthood, which increases over time. After adjusting for family background and postsecondary characteristics, black youth reported 85.8% more debt than their white peers when starting their careers, according to the authors.

This disparity grows by 6.7% annually, they said.

Racists will find any excuses to stop policies that reduce the wealth gap

Larsen 22 - Peter Larsen, 12-11-2022, "The Racial Impact and Rhetoric of Student Loan

Forgiveness," No Publication, https://www.civilrights.pitt.edu/racial-impact-and-rhetoric-student-loanforgiveness-peter-larsen // MH

On August 24, 2022, President Biden announced a three-part strategy to address the U.S. student debt crisis. [1] First, cancellation of up to $10,000 for borrowers who earned less than $125,000 per year, with an additional $10,000

available for Pell grantees. Second, providing relief to borrowers by fixing the well-known problems with the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program and cutting undergraduate loan monthly payments. Third, working to

control increasing costs of higher education going forward. Perhaps predictably, the major focus of attention in media and public opinion has centered around debt cancellation, and all but ignored the latter two parts of Biden’s

strategy. Outrage from conservatives was swift and broad. Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) claimed that the working class might “get off the bong” and vote for the Democrats in the 2022 midterm elections. [2] A group of Republican

Congresspersons voiced concern that Biden’s limited student loan cancellation would depress military recruitment, citing the military’s coverage of educational costs for some armed service members as a chief recruitment

incentive. [3] Even more conservative pundits and politicians argued against student debt cancellation on general principle, with arguments ranging from the offense debt forgiveness causes to those who had already paid off their

student loans, [4] to even more outlandish claims. [5] While some, like the ACLU exerted pressure on Biden prior to his announcement, arguing student debt cancellation is a racial justice issue, [6]

conservative

extremists called debt cancellation racism against white people. [7] Meanwhile, the Biden White House was mostly concerned with

pointing out the perceived hypocrisy with many of the student debt cancellation critics having recently significantly benefitted from the federal government’s financial relief during the pandemic. [8] So, what is the truth regarding

race and student debt cancellation? By the numbers, federally held student loans makeup roughly 92% of student loan debt, or $1.6 trillion, spread out over 43 million loan holders. [9] This is truly a major financial crisis for the U.S.

Who holds those loans? “In 2015–16, the percentage of full-time, full-year undergraduate students who received loans from any source also varied by racial/ethnic group. A higher percentage of Black students (71 percent)

received loans than students who were White (56 percent), of Two or more races (54 percent), Pacific Islander (53 percent), Hispanic (50 percent), American Indian/Alaska Native (38 percent), and Asian (31 percent)…. With respect

to Federal Pell Grants, Asian students received a higher average annual amount of aid ($5,030) than did Hispanic ($4,860) and White ($4,610) students. Students who were Black ($4,900), Hispanic, and of Two or more races

($4,830) also received higher average annual amounts of Pell Grant aid than did White students.” [10] What of the racialized rhetoric from the right? Research has shown conservatives perceive a greater racial correlation with

marijuana usage than liberals. [11] The actual data, however, shows that “in 2018 the lifetime prevalence of cannabis use was lower for Black (45.3%) than White (53.6%) adults aged 18 years or older, but Black individuals were

3.64 times more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession.” [12] In terms of military service, “In 2004, 36% of active duty military were black, Hispanic, Asian or some other racial or ethnic group. Black service members made up

about half of all racial and ethnic minorities at that time. By 2017, the share of active duty military who were non-Hispanic white had fallen, while racial and ethnic minorities made up 43% – and within that group, blacks dropped

from 51% in 2004 to 39% in 2017 just as the share of Hispanics rose from 25% to 36%.” [13] Interestingly, one of the greatest racial disparities around President Biden’s announced plan actually has to do with the PSLF program.

Black or African Americans are more likely to support PSLF [Loan Forgiveness] than

any other race,” and “White or Caucasian Americans report the least support for PSLF.” [14] In many ways, there is a great benefit to Black people in

While “[o]ne-third of Americans support PSLF, “

student loan forgiveness. At the same time, the benefit to the Black community is perhaps overstated. The larger issue at play is the conflation of race and socioeconomic status. The relationship between the two is complex, and

well documented, but poorly understood. Current census statistical research shows that “race and ethnicity in terms of stratification often determine a person's socioeconomic status.” [15] Many of the benefits of student debt

cancellation are more impactful along socioeconomic lines than racial lines. From the Brookings Institute, “we know that white families have about eight times the amount of wealth as Black families, and that really comes out of

the wash in terms of who repays student loans, what kind of time period, as well as default rates. And we know that Black borrowers take much longer time to cancel or to eliminate their loans, to pay down their loans, and also

conservative groups attempting to derail Biden’s student debt cancellation will remain myopic about the perceived racial benefits of

debt forgiveness. One of the legal challenges to the plan is from the Brown County Taxpayers Association, which claims that debt cancellation “violates federal law by

intentionally seeking to narrow the racial wealth gap and help Black borrowers.” [17] (The group’s emergency

their default rates are higher.” [16] Still, it seems that the focus of

application for writ of injunction pending appeal was recently rejected by the Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who serves as the Circuit Justice for the lawsuit, as well as the preceding federal judge and appellate judge panel.

[18]) It remains incumbent on academics to continue correcting the record and drawing necessary fine distinctions relating to racially based misinformation and disinformation around student debt cancellation as these lawsuits

continue to wend their way through the courts and remain a topic of discussion in the popular media.

Rebuttal

Capitalism is to ingrained to eliminate; we have to work within the system to promote

change

Dr. John K. Wilson, Institute for College Freedom, “How the Left can Win Arguments

and Influence People,” 2001, ["Project MUSE", https://muse.jhu.edu/books/9780814784587] JMS

Capitalism is far too ingrained in American life to eliminate. If you go into the most impoverished areas of America, you

will find that the people who live there are not seeking government control over factories or even more social welfare programs; they're

hoping, usually in vain, for a fair chance to share in the capitalist wealth. The

poor do not pray for socialism-they strive to

be a part of the capitalist system. They want jobs, they want to start businesses, and they want to

make money and be successful. What's wrong with America is not capitalism as a system but

capitalism as a religion. We worship the accumulation of wealth and treat the horrible inequality between rich and poor as if it were

an act of God. Worst of all, we allow the government to exacerbate the financial divide by favoring the wealthy: go anywhere in America, and

compare a rich suburb with a poor town-the city services, schools, parks, and practically everything else will be better financed in the place

populated by rich people. The

aim is not to overthrow capitalism but to overhaul it. Give it a social-justice

tune-up, make it more efficient, get the economic engine to hit on all cylinders for everybody, and stop putting out

so many environmentally hazardous substances. To some people, this goal means selling out leftist ideals for the sake of capitalism. But the

right thrives on having an ineffective opposition. The Revolutionary Communist Party helps stabilize the "free market" capitalist system by

making it seem as if the only alternative to free-market capitalism is a return to Stalinism. Prospective

activists for change are

instead channeled into pointless discussions about the revolutionary potential of the proletariat.

Instead of working to persuade people to accept progressive ideas, the far left talks to itself.

On the Alt: Turn- Social Movements must come through existing institutions or they

will never succeed--- the neg only reinforces the status quo

Alasdair Roberts, Suffolk University Law School, Public Administration Review,

2012 [“Why the Occupy Movement Failed” http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.15406210.2012.02614.x/full , 7-2-2017 ] AWS

Th e Occupy movement briefly flourished and then failed. It burned itself out without moving the country substantially closer to remedies for

any of the problems associated with the neoliberal project. In a sense, it demonstrated some of the reasons for the resilience of that

project. Neoliberalism has reshaped politics as well as the economy. It destroyed mechanisms such as the union movement that

might have organized resistance against it and gave authorities more extensive capabilities for policing

mass protest. Granted, it provided its opponents with improved technical capabilities for mobilization; but at the same time, it encouraged

the illusion that these new technical capabilities would allow the possibility of organization without hierarchy. In this way, neoliberalism

unwittingly incapacitated its enemies. Taken to an extreme, the horizontalist ethic destroyed the capacity of Occupiers to build political

alliances and curb behavior that would corrode popular support and trigger robust policing. Th e anarchist philosophy promoted by many

activists within OWS contemplates only three possible paths to social change. One is violent resistance against established authority. As we

have seen, this is ineffectual when governments have increasingly robust policing capabilities. (And in any case, many anarchists would not

choose violence as a matter of principle.) A second path is the gradual subversion of the status quo through the creation and growth of

alternative modes of social organization—that is, “building the new society in the shell of the old” (Byrne 2012, 142). But this presumes the

ability to persuade a broader public that it should collaborate in expanding the anarchist experiment. To do this, the experiment would have to

be seen as something worth joining, and as the months passed, fewer and fewer Americans viewed OWS in this way. Many liked its goals; most

did not like its modus operandi. Th is leaves only the third path to social change: working

through existing political

institutions. This path is dismissed by anarchists because existing structures are thought to lack

legitimacy. But if the fi rst and second paths are obstructed, it is imprudent to dismiss the third out of

hand. The alternative is to give up on the possibility of social change entirely. To succeed on this third path,

however, opponents of neoliberalism must acknowledge three points. The first is that an opposition movement must have the capacity to

coordinate and control action, which OWS clearly lacked. Second, it must have a philosophy of action that concedes the possibility of tactical

alliances with other social actors. And third, it

must have an overarching view about the role of state and economy—

a new paradigm—that explains in a concise and appealing way its alternative to the status quo and

forestalls unending debate about what the demands of the movement should be. Th ere may be a good,

convenient example of a cause that did all of this: neoliberalism itself, as it became ascendant in the tumult of the 1970s.

2. Do Both: the net benefit Capitalism is not monolithic, but their K makes it so.

Instead, we should affirm everyday experiences of alterity and smaller actions like the

plan as a way to create ethical connections and cultivate subjectivities not alreadyinterpolated by capital.

Agnes N. Sui and Ngai Pun, Agnes S.Ku is Associate Professor of Sociology at Hong

Kong University of Science and Technology. Ngai Pun is Assistant Professor of

Anthropology at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Routledge Curzon

Studies in Asia’s Transformations, 2005 [“Remaking Citizenship in Hong

Kong” http://www.untagsmd.ac.id/files/Perpustakaan_Digital_1/CITIZENSHIP%20Remaking%20Citizenship%20in%20Hong%20Ko

ng%20Community,%20nation%20and%20the%20global%20city.pdf 10.04.15]-BHAJr

Gibson-Graham and colleagues have engaged in such a project by bringing in the experience of ordinary people in order to gain “a new positioning in the grammar of economy.” They have worked as a group since 1997 consisting

They do not see the economy and capitalism as a

monotonous entity; for them to call the economy capitalist is to engage in “categorical violence.” As a

result, it is desirable to develop new languages “to represent noncapitalist forms of economy

(including ones we might value and desire) as existing and emerging, and as possible to create” (ibid.: 95). Their

cultivation of alternative economic subjectivities is realized essentially through creating a new economic language and by rearticulating it with existing economic processes. For them, many of the diverse

everyday activities of ordinary people, such as community and ecological services, household

management, voluntary and religious works, can be seen as diverse “economic practices” but they are

disqualified as “non-economic” by mainstream economic language and are thus marginalized as

secondary or insignificant. In order to reclaim their centrality in the economy, Gibson-Graham develops a typology that regards

these practices as economic (but not capitalist) activities.3 In other words, what Gibson-Graham advocates is to broaden and to open up the meaning of the

of “members who hoped to become desiring economic subjects of a ‘socialist’ sort” (CEC 2001:94).

economy, instead of reducing everything into a narrowly defined economistic domain. To cultivate a “desiring economic subject” of a “socialist sort” requires integrating two apparently contradictory ethical principles. The first is

conventionally associated with the economic domain: being an autonomous self that is independent, free and assertive. The second is considered to fall into the communal domain: being a communal subject who is caring, willing

. To reconcile these seemingly contradictory principles, the meanings of

“economic” and “community” have to be reconsidered. On the one hand, the homogenizing and exclusive tendencies that limit or even suppress community

to share and is concerned with collective welfare

members’ freedom and autonomy have to be avoided, and the meaning of “community” could just as well be understood in terms of difference. On the other hand, to balance the selfish, indifferent, and atomizing tendencies of

individualism, the economic subject can be reconceptualized as mutually respecting and supportive subjects who are able to maintain feelings of common interest and sympathy but at the same time to keep a critical distance from

communal cohesion and domination. In Hong Kong, as elsewhere, unlike other keywords with contested meanings (perhaps the most notable one is “globalization”), the term “community” is rarely used unfavorably. Rebuilding

This is particularly true in

this current recession period in which the community is increasingly accepted as an alternative to the

malfunctioning market economy and the retreating state. Yet in light of the not-always-positive experiences of various kinds of community projects in the past,

community is an acceptable political agenda for almost all social forces differentially located along political spectrums, from conservatives to liberals to the radicals.

it is still worthwhile to swim against the current in order to rethink the meaning of community before endorsing its liberation potential. What is a “community”? The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines a community as: I.

A body of individuals: 1. The commons as opposed to peers etc.; the common people. 2. An organized political, municipal, or social body; a body of people living in the same locality; a body of people having religion, profession, etc.,

in common; a body of nations unified by common interests. 3. A monastic, socialistic, etc. body of people living together and holding goods in common. II. A quality or state: 4. The state of being shared or held in common; joint

ownership or liability. 5. A common character, an agreement, an identity. 6. Social inter-course; communion; fellowship, sense of common identity. 7. Commonness, ordinary occurrence. 8. Life in association with others; society;

the social state. In other words, in addition to its connotation of its detachment from the state and its difference from “peers” or those of rank, “community” often connotes “commonness,” “sameness” or even “oneness.” From

the nineteenth century onwards, “community” has become a term that implies “experiments in an alternative kind of group-living,” whose constituency is always disadvantaged populations. The term has increasingly detached

To many social activists, the ideal

“communal subject” is one who actively shapes his/her own future by engaging in various communal

relationships, promoting shared interests and constructing common identities. Yet in light of past negative experiences of various

from national politics and official social welfare provision, and come closer to denote “working directly with people” (Williams 1976:75–76).

kinds of community projects, such as the exclusive tendencies of the community and its restriction of individual autonomy and freedom, the term “community” has increasingly been rethought in recent

studies. When community is understood as a geographically bounded locality with the following

characteristics: intimacy, immediacy, reciprocity, transparency, assimilation, shared interests, shared

identities and local autonomy, it is often used as a (utopian) political model that could serve as an

alternative to both the atomizing individualism and a panoptical surveillant state. Yet in a cosmopolitan setting such as

sociocultural

contemporary Hong Kong, communities are inevitably border-crossing. Shared or common interests with a particular group/community are always partial. Even in a given geographical locality, it is not easy to put different groups

of persons together by assigning them a common identity, as the interests of different ethnic, gender, income and age-groups are very diverse. Elaborating Iris Young’s critical notion of community, Jeannie Martin (Martin and

O’Loughlin 2002) nicely argues that the model of a small neighborhood that celebrates face-to-face relations is inadequate to mediate among strangers and their unassimilated differences. Moreover, this model of community that

privileges commonness and sameness is blind to adverse political consequences such as exclusiveness and intolerance of difference. Hence, as Martin argues, broader networks such as administrative, political, economic, cultural

ones are crucial to communal projects in complex societies, for without these networks the democratic and inclusive encountering of strangers will be impossible. That is why Martin believes that community development should

be understood largely as cultural work or cultural mediation that aims at constructively handling “constellations of meanings, practices, identifications.” What Young and Martin proposed could be framed as

“community of difference.” As Cameron and Gibson (2001:17) suggest, “communities of difference”

are nothing but “fluid process[es] of moving between moments of sameness and difference, between

being fixed and ‘in place’ and becoming something new and ‘out of place.’” This opens up a

possibility, though not easy to realize, of reconciling the apparent contradiction between communal

relationships and independence/freedom of the individual.

the