Goa Mining: Economics, Ethics, and Environmental Impact

advertisement

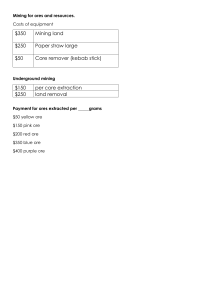

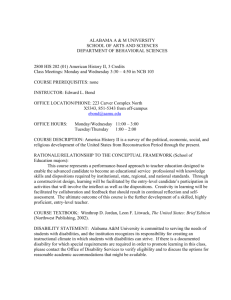

DISCUSSION Mining in Goa: Beyond Forest Issues Rahul Basu This comment on “Missing the Woods for the Ore: Goa’s Development Myopia” by Pranab Mukhopadhyay and Gopal K Kadekodi further criticises “A Study on Goan Iron Ore Mining Industry”, the 2010 report of the National Council of Applied Economic Research. P ranab Mukhopadhyay and Gopal K Kadekodi (“Missing the Woods for the Ore: Goa’s Development Myopia”, EPW, 12 November 2011) (MG hereafter) have critiqued a report on mining in Goa by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) (2010) for using incorrect methodology in comparing forest’s values and mining deposits. We feel that MG’s critique omits some other deficiencies in the report of NCAER that have important implications. Ethical Concerns One important gap in MG is the discussion of research ethics. NCAER should also have freely disseminated its report through its website or priced it reasonably for interested readers. Instead, the 62-page report is priced at Rs 1,000, ensuring that an average concerned citizen does not buy it. Further, as a leading Indian economic think tank, NCAER should have followed international best practice (McCullough and McKitrick 2009) and placed both the source data and their calculations in the public domain for independent verification and analysis. This comment, therefore, raises larger questions on the need for a code of ethics by professional organisations.1 Methodological Issues The author would like to acknowledge helpful inputs from Pranab Mukhopadhyay and Sudipta Basu. Rahul Basu (rahulbasu1@gmail.com) is the founder and CEO of Ajadé. Economic & Political Weekly EPW january 21, 2012 The three principal conclusions of NCAER (2010) are: (1) Mining contributes around 5% of Goa’s gross state domestic product (GSDP) when measured at constant 1999-2000 prices. The price of world iron ore increased sharply in January 2008. The NCAER report (2010) re-estimates the share of mining in Goa’s GSDP and anticipates this to be the longterm contribution assuming that the higher iron prices are permanent. At current (2007-08) prices, this would imply a direct as well as indirect contribution by mining of 16.94% of GSDP (ibid: 26). vol xlviI no 3 (2) The NCAER report claims that in 2004-05, mining employed directly and indirectly about 75,000 workers of the state’s workforce of 5,82,274. This is close to estimated tourism employment of 84,150 (ibid: 18). (3) The opportunity cost of giving up the iron ore industry would be greater than the cost of environmental losses (ibid: 43). Mining Share of GSDP: The anticipation of NCAER’s report that the iron ore price rise is permanent is rather optimistic as commodity prices are cyclical. The iron ore market is highly concentrated with a few large buyers and sellers. The big buyers are steel manufacturers in China, Japan and Korea. The big iron ore suppliers are Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton and Vale. For nearly 40 years, the buyers and sellers had negotiated to set long-term iron ore prices. However, as commodity demand surged in 2007, this arrangement broke down and prices rose sharply in January 2008 (Handique 2007). Sesa Goa, the largest Goan iron ore exporter contributed 35% of Goa’s iron ore exports in 2009-10 (GMOEA 2010: 5). The annual report of Sesa Goa states that “…supply-side constraints of the past are expected to change by 2014. …What this means is that….The world may see an over-supply condition by 2014 at the macro level…”.2 In other words, the leading industry player expects iron ore will be in oversupply in a few years ­resulting in a steep drop in prices. Further, Goan export price per tonne dropped by 33% between 2007-08 and 2008-09 from Rs 3,017 per tonne to Rs 2,012 per tonne (derived from port-wise iron ore export data, NCAER 2010: 18). Clearly, there is an expectation in the iron ore industry that the demandsupply imbalance will soon be bridged. Thus, NCAER’s price expectations are poorly informed and iron ore should be expected to maintain its contribution at around 5% of Goa’s GSDP as anticipated by the constant price series of Goa government’s Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation (DPSE). NCAER’s calculations to create this inputoutput table have not been placed in the public domain. There seem to be several inconsistencies. For example, see Table A2 (NCAER: 56). 77 DISCUSSION (1) On the cost side, transportation is taken to be 9%, whereas the financial statements of Sesa Goa show that 49% of the expense (for the company as a whole) is for transportation.3 (2) Rows indicate the estimated output allocated according to uses, including final demand. NCAER estimates that 45% of the mining output is consumed in Goa (Table A2). Unlikely users include construction (13%) and electricity, gas and water supply (13%). In reality, almost all Goan iron ore is exported – GMOEA reports it as over 100% (GMOEA 2010: 1). NCAER then calculates the following ­results for the multipliers: people usually working in Goan mining and quarrying is 3,412, plus hired workers numbering 3,161, totalling to 6,573. For reasons unstated, NCAER ignores this ­official data source. NCAER also uses estimates for direct and indirect employment from mining from its funding agency GMOEA. There are few explanations or sources provided for GMOEA’s estimates of 75,000. Our own calculations on Goa’s mining employment suggest that the total employment (direct and indirect) would not exceed 21,873. Direct Employment: In 2009-10, Sesa Goa Table: Multipliers Estimated by NCAER had 2,691 employees based in Key Sectors Only Value Output Employment Employment Income Goa.6 We add another 1,200 Addition Multiplier Multiplier (Person Years Multiplier (Person Years of Calculated) employees of V S Dempo, Per Lakh of Output which was acquired by Sesa at 2007-08 Prices) Goa during the year7 totalMining and quarrying 0.7787 1.45 0.41 71,600 0.98 Agriculture 0.7262 1.52 3.41 2,73,970 1.02 ling 3,891 employees. This inManufacturing 0.2478 2.35 0.84 4,71,809 0.82 cludes employees in a variety Construction 0.3422 2.31 0.83 1,10,202 0.93 of non-mining activities such Trade, hotels as pig iron, metallurgical and restaurants 0.7543 1.44 0.76 1,36,183 0.99 Source: NCAER 2010 (pp 10, 26 and 57). coke and ship-building/ship The income multiplier shows us the total yards, as well as employees for operating direct and indirect value addition due to vehicles, river fleet, aircraft and ships. increase in one unit of output. Alarmingly, Sesa’s iron ore segment’s operational exif we were to use the NCAER (2010) methodo­ pense was 80.5% of the total operational logy, manufacturing would be responsible expenses and 72.7% of the total iron ore for 108% of GSDP.4 was in Goa. If we were to proportionately Even if these multipliers accurately rep- estimate employment to only Goan iron resent the Goan economy, NCAER’s calcu- ore (73%), we get a figure of 2,277 lations suggest that (1) the mining em- (=3,891*.805*733). ployment multiplier is the lowest among The Goan iron ore industry exported 2.85 all other leading sectors. (2) The income times that of Sesa and Dempo in 2009-10 multiplier is lower than agriculture and trade, hotels and restaurants (tourism). Employment: The NCAER report would like the reader to believe that mining is a large contributor to employment in Goa. Initially, NCAER arrives at direct employment using data from the National Sample Survey 61st Round 2004-05. In the process, NCAER oddly assumes “the population in rural ­areas to be insignificant in Goa” (NCAER 2010: 17). Interestingly, NSSO itself estimates that 61.5% of Goans reside in ­rural areas (GoI 2005: A-5 and A-7). However, NCAER concludes that the labour force directly employed in mining and quarrying is 19,000, out of a total Goan labour force of 5,82,000. Contrarily, the Fifth Economic Census in 20055 reports that the total number of 78 (GMOEA 2010: 5). Goan iron ore exports in 2008-09 were 83.3% of that in 2009-10 (ibid: 1). By extrapolating the Sesa Goa employment figure we get total direct employment of 5,416 (= 2,277 × 2.85 × 0.833). Indirect Employees: GMOEA estimates total indirect employment to be at 1:1 ratio with direct employment. In the absence of any other indicators, we use GMOEA’s ratio to estimate that indirect employment in mining is 5,416. Truck Transportation: We assume that a truck traverses 5,000 km a month, for seven months of the year (non-monsoon), and carries 10 tonnes.8 Goa exported 38.075 mn tonnes in 2008-09 (GMOEA 2010: 1) and the average road linkage from the mine to the river loading point is 30 km,9 arriving at a total of 228 million truck kilometres. The overburden is 2.3 times more than the production.10 Assuming the average truck run is 2 km for the overburden, we get 18 mn truck km for overburden. Total truck transportation is 246 mn truck km. Based on 35,000 km per annum per truck (a very conser­vative utilisation level for a commercial vehicle), we get 7,028 trucks. In 2005, there were 55,119 commercial vehicles in Goa11 and an estimated 63,000 people employed in transportation.12 The latter figure includes buses with conductors. We, therefore, estimate one direct employee per truck and the total employed on trucks as 7,028. Lacking another methodology, PERSPECTIVES ON CASH TRANSFERS May 21, 2011 A Case for Reframing the Cash Transfer Debate in India – Sudha Narayanan Mexico’s Targeted and Conditional Transfers: Between Oportunidades and Rights – Pablo Yanes Brazil’s Bolsa Família: A Review – Fabio Veras Soares Conditional Cash Transfers as a Tool of Social Policy – Francesca Bastagli Cash Transfers as the Silver Bullet for Poverty Reduction: A Sceptical Note – Jayati Ghosh PDS Forever? – Ashok Kotwal, Milind Murugkar, Bharat Ramaswami Impact of Biometric Identification-Based Transfers – Arka Roy Chaudhuri, E Somanathan The Shift to Cash Transfers: Running Better But on the Wrong Road? – Devesh Kapur For copies write to: Circulation Manager, Economic and Political Weekly, 320-321, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013. email: circulation@epw.in january 21, 2012 vol xlviI no 3 EPW Economic & Political Weekly DISCUSSION we use GMOEA’s scale factor of 25% of truck transportation to estimate Goan ­employment in garages, etc, as 1,757. Barge Transportation: The number of barges in Goa in 2009 was 300 (GMOEA 2010: 13). Only 83.5% of the iron ore exported from Goa was of Goan origin (GMOEA 2010: 1). Therefore, 251 barges were used for transporting Goan iron ore. Articulated tugs and barges are reported to have seven to nine crew members.13 The last two capsized Goan iron-ore barges reported seven employees each.14 Direct employment on 251 barges would, therefore, be 1,754. Supervision for 251 barges could be considered as two per barge or 502 supervisors. Summing-up the estimates above, we arrive at a bottom-up employment figure of only 21,873 (5,416 + 5,416 + 7,028 + 1,757 + 1,754 + 502). As mining stops during the monsoon, all of the transportation employment and most of the direct mining employment are seasonal and manned by migrant workers. Assuming that only 50% of the direct mining employment is in categories that persist during the monsoons, the real core employment of Goa is unlikely to exceed 5,500 (rounding up from 5,416 above). Social Benefits: Since NCAER’s third conclusion has been critiqued intensively by MG, we focus on estimating only the social cost due to depletion of natural reserves. We will use the net price methodology used by the World Bank (WB 1997: 8). This is easy to measure but can give an upward bias in a high-price environment. In essence, it calculates the price of the iron ore minus the cost of extraction, multiplied by the amount extracted. The cost of extraction includes the cost of capital. Society captures some of this economic rent through royalties. Most of it is captured in the profit before tax of the mining companies. In 2008-09, Sesa Goa reported profit before interest, tax, dividends and other non-recurring or non-allocable expenses for the iron ore segment amounting to Rs 2,206.07 crore.15 Segment assets are Rs 902.69 crore and depreciation is Rs 34.95 crore. Using a 12% cost of capital rate, we calculate depletion cost at Rs 2,062.80 crore.16 Sesa’s corporate tax rate was Economic & Political Weekly EPW january 21, 2012 26.3922%. Adjusting for this, we get a depletion cost of Rs 1,518.38 crore. Sesa’s production in 2008-09 was 41.9958% of the total Goan iron ore exports (GMOEA 2010: 1 and 21). We, therefore, calculate a total depletion cost of Rs 3,615.55 crore (=1,518.38 ÷ 41.9958%), which is much in excess of the annual social benefits of Rs 2,309.5 crore (NCAER 2010: 43). 10 11 12 13 14 Implications for State Policy The inescapable conclusion is that mining should be stopped, or at least drastically curtailed, in Goa. The state policy should take into account a likely steep decline in iron ore prices in the near future. Goa needs better studies in environmental management that not only use state-ofthe-art methods, but also maintain the highest standards in research ethics. NCAER (2010) report is unacceptable on both these dimensions. Closure of mining, by our calculations, would affect a resident population of about 5,500 (about 0.9% of Goa’s labour force). Finding alternative employment may be much easier than what NCAER and GMOEA would have us believe. A state which is growing at over 10% per annum in real terms should be able to absorb the displaced workers in other sectors. Notes 1 Tilman Börgers in the website “Conflict of Interest in Economics”, viewed on 8 August 2011, https:// sites.google.com/site/cointrest/home 2 Annual Report 2009-10, p 8, Sesa Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011, http://www.sesagoa. com/attachments/article/115/Sesa%20Goa%20 Ltd%20Full%20Version%20ARFY2010.pdf 3 See Note 2, p 107. 4 Mining contributes 10.14% of SGDP at current prices. NCAER calculates the direct and indirect contribution of mining by the formula 0.98/0.78* 10.14=12.74% (NCAER 2010:26). Using the same methodology, manufacturing contributes 32.63% of SGDP. Using the same methodology, we get 0.82/0.2478*32.63=107.97. 5 See DPSE (2005b). 6 P 29, Sustainability Report 2009-10, Sesa Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011 (http://www.sesagoa.com/attachments/article/114/Sesa%20final %20pdf%20for%20web%20upload%20.pdf). 7 Annual Report 2009-10, Sesa Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011, p 28 (http://www.sesagoa.com/ attachments/article/115/Sesa%20Goa%20Ltd%20 Full%20Version%20ARFY2010.pdf 8��������������������������������������������� Annexure C, “Environmental and Social Performance Indicators and Sustainability Markers in Minerals Development: Reporting Progress towards Improved Ecosystem Health and Human Wellbeing”, Phase III, TERI Project Report No 2002WR41, TERI – Western Regional Centre, Goa, viewed on 26 June 2011, http://idl-bnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/10625/33366/1/125313.pdf 9 “Mineral Resources of Goa – IRON”, Directorate vol xlviI no 3 15 16 of Mines and Geology, Government of Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011 (http://www.goadmg. gov.in/ironinfo.htm). “Mining Areas”, Directorate of Mines and Geology, Government of Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011. (http://www.goadmg.gov.in/miningarea.htm). See DPSE (2005a). See DPSE (2005b). “Tugboats”, Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, viewed on 11 July 2011, (http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Tugboat). “Barge Capsizes Near MPT Crew Rescued”, O Heraldo (19 March 2011), “Loaded Barge Capsizes at MPT”, The Times of India, 20 March 2009, viewed on 27 June 2011, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2009-03-20/goa/28017448_1_ barge-owner-bad-weather-mpt. P 121, Annual Report 2009-10, Sesa Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011 (http://www.sesagoa.com/ attachments/article/115/Sesa%20Goa%20Ltd%20 Full%20Version%20ARFY2010.pdf). Cost of capital = Rs 108.32 crore (Rs 902.69 * 12%). Total return on capital + depreciation is Rs 143.27 crore (108.32+34.95). Depletion cost is Rs 2,206.07 crore – Rs 143.27 crore = Rs 2,062.80 crore. References DPSE (2005a): Statistical Hand Book of Goa 2003-04 and 2004-05, Department of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation, Government of Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011 (http://goadpse.gov.in/publications/ dpse-goa-stathandbook0304-0405.pdf). – (2005b): Report on Fifth Economic Census, Department of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation, Government of Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011. (http://goadpse.gov.in/publications/goa-ecocensus-report-2005.pdf). GMOEA (2010): “GMOEA Selected Statistics 2009-10”, Goa Mineral Ore Exporters Association, Panaji. Handique, Maitreyee (2007): “NDMC Effects Hefty Increase in Ore Prices”, Livemint, 29 December, viewed on 26 June 2011. McCullough, Bruce D and Ross McKitrick (2009): Check the Numbers: The Case for Due Diligence in Policy Formation, Fraser Institute, Vancouver. NCAER (2010): “A Study of Goan Iron Ore Mining Industry”, National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi. NSSO (2005): National Sample Survey Report 515: Employment and Unemployment Situation in India, 2004-05, National Sample Survey Orga­nisation, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi, viewed on 26 June (http://www.mospi.gov.in/mospi_ nsso_rept_pubn.htm). OH (2011): “Barge Capsizes Near MPT Crew Rescued”, O Heraldo, 19 March, viewed on 27 June 2011, (http://oheraldo.in/news/main%20page%20news/ Barge-capsizes-near-MPT-crew-rescued/18902. html). Sesa (2010a): Annual Report 2009-10, Sesa Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011 (http://www.sesagoa. com/attachments/article/115/Sesa%20Goa%20 Ltd%20Full%20Version%20ARFY2010.pdf). – (2010b): Sustainability Report 2009-10, Sesa Goa, Panaji, viewed on 26 June 2011 (http://www.sesagoa.com/attachments/article/114/Sesa%20final %20pdf%20for%20web%20upload%20.pdf). TERI (2006): Environmental and Social Performance Indicators and Sustainability Markers in Minerals Development: Reporting Progress towards Improved Ecosystem Health & Human Well-being, Phase III, TERI Project Report No 2002WR41, TERI – Western Regional Centre, Goa. TOI (2009): “Loaded Barge Capsizes at MPT”, The Times of India, 20 March. WB (1997): Expanding the Measure of Wealth: Indi­ cators of Environmentally Sustainable Development, Environment Department, World Bank, Washington DC. 79