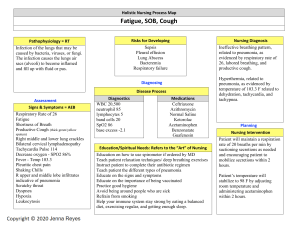

IAP Navi Mumbai’s NMAP Infectious Disease Practical Tips Series 2023 Authors: Dr Vijay Yewale, Dr Jagdish Chinappa Dr Jeetendra Gavhane, Dr Dhiren Gupta, Dr Mangai Sinha With the full-fledged resumption of school post covid, the winter and monsoon seasons in the years 2022-23 saw a tremendous surge in children presenting with cough, cold, fever, and varying degrees of respiratory distress with or without wheeze. The incidence of adenoidal hypertrophy, as well as middle ear infections, was also unusually high. Lack of immune exposure during the lockdown led to frequent and recurrent episodes of respiratory illnesses amongst school going children post covid, causing parental concern. In an approach to this clinical respiratory syndrome seen in day to day practice, IAP Navi Mumbai started an Infectious Disease Practical Tips Series to guide practitioners in diagnosing and managing common respiratory illnesses as well as other infectious diseases. The tips were circulated on social media three a week over a span of four months. Below is a compilation of all the tips in the first part of this series. Compiled by: Dr Priyanka Amonkar, EB Member, IAP Navi Mumbai Regards, Team IAP Navi Mumbai Dr Satish Shahane, President, IAP Navi Mumbai Dr Mangai Sinha, Secretary, IAP Navi Mumbai Dr Amit Saxena, Treasurer, IAP Navi Mumbai Dr Vikram Patra, Joint Secretary, IAP Navi Mumbai Dr Jeetendra Gavhane, Scientific Convenor, IAP Navi Mumbai TIP 1 (Contributor: Dr Vijay Yewale) Fever, cough & rapid breathing is a common syndrome seen in practice. The 4 common causes for this are: 1. Bronchiolitis 2. Viral infections with or without wheeze 3. Asthma (Hyper Reactive Airway Disease) 4. Pneumonia There are clinical clues to differentiate one from the other. o Bronchiolitis is usually seen as an outbreak from Sept- Jan, in kids from 2 months to 2 years. o The kid has insidious onset tachypnea, rhonchi, may have a few crepts but is not sick looking, and is very often happy despite tachypnea and wheeze. Often, there is a prodrome of a leaky nose and close contact with a viral illness. o Bronchiolitis must also be thought of in an infant with subtle respiratory symptoms and excessive crying due to air hunger. o So a happy tachypneic wheezing infant is likely to be a bronchiolitis kid. TIP 2 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) Wheeze Associated Lower Respiratory Infection (WALRI) is another cause of fever, cough, and rapid breathing (tachypnea). It is also called Virus Associated Wheeze (VAW). o Usually seen in kids from 6 months to 5 years. o These are generally discrete episodes of viral infections. They may be recurrent, up to a minimum of 3-4 wheezing episodes in a year. o Often, a history of preceding viral infection, age of the child, and response to inhaled bronchodilators help come to a diagnosis. It is a good practice to flip through the past records and see if the child has received an oral bronchodilator, nebulization, or a LTRA like monteleukast in the past. o WALRI is a viral infection and needs only symptomatic treatment in the form of a bronchodilator, oral or inhaled. An antibiotic is not required. It is important to remember that wheezing may not be appreciated in a child if he is already on bronchodilators. o Although viruses are the most common triggers of wheezing in childhood, in some children, respiratory viral infection will induce transient and episodic wheezing episodes, while in others, wheezing with respiratory viruses will also influence the future development of asthma in the child. o For all wheezers below 5 years of age, other conditions that mimic asthma need to be ruled out. o The presence of atopic features like allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and a family history should raise suspicion of a high risk for asthma, and a trial of ICS can be given. Montelukast in short courses is of no use and should not be given. o If the history is suggestive of typical viral induced wheezing or asthma, no investigations are necessary. TIP 3 (Contributors: Dr Mangai Sinha, Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) Asthma should be diagnosed confidently in a child above 5 years with recurrent episodes of airway obstruction manifested by cough, wheeze, and difficulty breathing, which is reversible by salbutamol with and without steroids. o Fever is not a prominent feature. Cough is mainly nocturnal and early morning, maybe aggravated by activity (running, exercise, eating, laughing, etc). o The wheeze is a bilateral polyphonic wheeze, typically reversed with a bronchodilator. o A family history of atopy and the presence of atopic features like atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis strongly suggest asthma. A good history can usually clinch the diagnosis and the probable triggers in most cases. Other co-existing allergic conditions also need to be looked for and treated simultaneously. o In children above 5 years, documentation of variable expiratory airflow limitation by spirometry (FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC) and positive bronchodilator reversibility is helpful and can be easily done. o It is important to note that a chest X ray is done only to rule out alternative conditions and is not required for the diagnosis of asthma. TIP 4 (Contribtors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) As discussed previously, when faced with picture of fever, cough & rapid breathing, there are three common conditions to be considered: Bronchiolitis, Wheeze precipitated by a viral infection and Pneumonia. o If the child has mild symptoms without respiratory distress, ambulatory care is advisable. o If the child has moderate to severe symptoms and signs, frequent observation in the emergency room and / or admission is advised. o X-ray chest may be indicated in moderate to severe cases. o CBC and CRP are not useful to guide treatment. o Newer modalities of PCR based rapid Point Of Care tests may help in determining the cause of respiratory distress and avoid the use of antibiotics. TIP 5 (Contribtors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) o Mild bronchiolitis is treated with simple saline nose drops and parents can be asked to come back in case the respiratory distress increases, the child gets irritable or develops difficulty in feeding. o Cold or cough mixtures containing antihistaminics, mucolytics, and cough suppressants are best avoided. Home remedies like simple fomentation of the chest and back may be tried. o Airway narrowing is more due to bronchiolar wall edema than bronchoconstriction. o The distinction between bronchiolitis and wheezing precipitated by a viral infection may be challenging. A trial of an oral bronchodilator like salbutamol may be given to a wheezing child and continued only if there is significant relief. Repeated nebulization is of no use. o Moderate to severe bronchiolitis needs hospitalization, hydration and oxygen to maintain saturation. Steroids and antibiotics have no role in the treatment of bronchiolitis. o While diagnosis of typical bronchiolitis can be made on clinical grounds, there could be difficulty in differentiating it from a viral or bacterial pneumonia. Monitoring the clinical course of the illness, along with an X-ray of the chest, may help. Clinical pneumonia needs to be treated with antibiotics. TIP 6 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) o A sick looking child with rapid breathing, respiratory distress, fever, cough, and crepitations has clinical pneumonia. o Virus infections usually involve the airway and secondarily, the parenchyma & interstitium. A focal lesion is usually bacterial. o While there is an overlap with WALRI and Bronchiolitis, usually pneumonia kids are sicker. X ray findings may lag behind clinical picture. o CBC & CRP are not very sensitive or specific to differentiate viral from bacterial. Higher neutrophils and higher CRP may be seen in bacterial pneumonia. Adenovirus and Influenza are known to cause elevation of CRP. o Nasopharyngeal swab testing is being increasingly used in kids with LRTI who are hospitalized. Observe caution when interpreting the results. Rhino/enteroviruses are commonly found and not the cause. Similarly, children carry pneumococci in the nasopharynx, and detection of it cannot be taken as the cause of pneumonia. H. influenza, Staph, and Pseudomonas are a few other commensals in the throat or nasopharynx. Influenza, RSV, Adenovirus, or Metapneumovirus usually indicate pathogenic associations in a child with pneumonia. TIP 7 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) o Any child of clinical pneumonia with fever, respiratory symptoms and increase in respiratory rate but no distress can be managed in the outpatient department with oral amoxicillin 40 mg / kg / day in 2-3 divided doses. o Parents should be counselled regarding close follow up and red flag signs of deterioration. o X-ray and Blood counts are usually not necessary. o Duration of antibiotic should be for 5-7 days, depending on response. TIP 8 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) Amoxicillin vs oral cephalosporin in outpatient treatment of pneumonia: o Amoxicillin is superior to cefpodoxime or cefdinir for OPD treatment of mild to moderate pneumonia, which is usually pneumococcal. o Oral cephalosporins have short half-lives, are poorly absorbed, are highly protein bound, and are dosed at long intervals. This results in serum concentrations that do not provide enough killing time (serum concentration over minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC]) to treat, except for organisms with a low MIC to a selected drug. o Amoxicillin reaches higher levels and is less protein bound, thus giving it more time with a drug concentration over the MIC. o Because the pharmacokinetics of oral cephalosporins are far inferior to amoxicillin, their use in CAP should be reserved for patients who are allergic to penicillin or patients with a cause known to be resistant to amoxicillin but susceptible to cephalosporins (i.e, M. catarrhalis or b lactamase–positive H influenzae). TIP 9 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr.Vijay Yewale) o Non focal community acquired pneumonia in children above 5 years of age, unresponsive to amoxicillin, should raise the flag for a possible mycoplasma infection. o Investigations are of limited value. o Judicious use of azithromycin may be indicated in select cases, as in pneumonia, where cough predominates and extrapulmonary manifestations are seen. TIP 10 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa Treatment of hospitalized children with moderate to severe Pneumonia but hemodynamically stable: o All pneumonias below age 3 months are treated as inpatients. o Control fever with paracetamol in adequate dose to reduce oxygen requirement. o Ensure proper hydration and nutrition. o Oxygen, if needed, to reduce work of breathing in a child with distress. o Injectable antibiotics: Ceftriaxone or co-amoxiclav is the empiric choice, with a similar spectrum covering both Gram-positive (Strep pneumo, Streptococcus, and MSSA) and Gram-negative (H. influenzae, Moraxella, and E. coli). o Empiric treatment with oseltamivir should be considered during an outbreak setting for hospitalized children with probable viral LRTI, low to normal counts, low or mildly elevated CRP, and non-lobar diffuse infiltrates on x ray. TIP 11 (Contributors: Dr.Vijay Yewale & Dr.Jagdish Chinappa) o Staphylococcus aureus is an important cause of CAP and should be considered in any sick child with moderate to severe pneumonia. o Presence of predisposing factors like post measles status, pyoderma, malnutrition and underlying influenza LRTI should raise the suspicion. o Toxin mediated rash and hypotension are other clues. o Staphylococcal strains are methicillin sensitive or resistant strains (MRSA and MSSA). o Both can produce the PVL toxin which can inhibit leukocyte function and progress rapidly. o Radiological features are usually a bronchopneumonia with predilection for a lobe. Presence of pneumatocoeles, necrosis and empyema are other features. o Attempts to get a microbiological confirmation with drug sensitivity should be done early. o Parenteral antibiotics should be started immediately to cover for both MRSA and MSSA. o Ceftriaxone / cloxacillin may be a good initial choice. o Addition of clindamycin or linezolid may be considered when there is high index of suspicion for toxin involvement. o Vancomycin is inferior to cloxacillin/ flucloxacillin for treatment of MSSA. o However, in a sick and hemodynamically unstable child, Vancomycin can be added upfront awaiting microbiological results. o Some labs have the facility to test for the PVL toxin. o The duration of treatment needed is usually prolonged and surgical evaluation for empyema may be needed. TIP 12 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale, Dr Dhiren Gupta & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) Adenoviral Infections o Acute Febrile Illness with varying presentations are seen: 1. Pharyngo-conjunctival fever: Some have tonsillar exudates. Unlike the typical GAS pharyngo- tonsillitis, odynophagia as presenting complaint is less common and so is the tender cervical lymphadenopathy. Snoring due to adenoidal hypertrophy and ear drum congestion with or without AOM is also seen in a few patients. 2. Some have associated gastroenteritis and pink eye (often unilateral conjunctivitis). 3. LRTI with or without complications. 4. Uncommonly adenoviral cystitis is seen. o Adenovirus is a DNA virus with more than 60 sub types. Severe disease has been associated with serotype 5, 7, 14 & 21. o Previously thought to be affecting children under 2 years and immunocompromised individuals, but this year we witnessed an outbreak where it’s behavior was very different and affected immune competent hosts as well. o Diagnosis may be confirmed by performing PCR on NP swab in severe or complicated cases. o Mild cases may be treated symptomatically on clinical grounds and need not be subjected to molecular diagnosis. o Antibiotics have no role. o Often associated with a high inflammatory response, fever can last longer, up to 2 to 4 weeks. o There are anecdotal reports of antiviral use in severe adenoviral disease in immunocompetent children. (author experience). IVIG/ Cidofovir has also been used in severe and progressively deteriorating adenoviral pneumonia. Progressive pneumonia with heavy viremia (blood PCR level) can be given Cidofovir with or without IVIG o Cidofovir: For induction treatment: 5 mg/kg IV over 1 hour, once a week x 2 weeks. Maintenance treatment: 5 mg/kg IV q2Weeks Vial - 75mg/mL (375mg/5mL vial) Infuse in 100 mL NS over 1 hr Hydration should be monitored while injecting Cidofovir as it is nephrotoxic TIP 13 (Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jagdish Chinappa) PCR based Testing is available to establish the etiology of upper and lower respiratory tract infections. Many packages are available depending on the local labs. o Most upper respiratory tract infections are self-limiting and do not require testing. o Those with a more prolonged or severe course may be tested. o The advantages of PCR based testing are: 1. Diagnose influenza and treat with oseltamivir. 2. Establish a viral etiology and avoid antibiotics. 3. Communicate with parents about the self-limiting nature of the illness. 4. Frequent follow up for an established adenoviral infection. o Those with lower respiratory infections needing hospitalization may be tested upfront. o Nasopharyngeal / Throat swab is often used for sample collection o The use and interpretation of the results from these samples require caution. o Influenza, Parainfluenza, Human metapneumovirus, RSV and Adenovirus are of clinical significance. o Rhino/echo viruses are usually not causally related. o In addition to viruses, PCR would also help in identifying pathogenic bacteria like pertussis and mycoplasma o Advanced PCR panels can be used in sick admitted patients to identify organisms and get an idea about antibiotic resistance. TIP 14 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) Microbiological diagnosis in a case of pneumonia is often difficult and ambiguous even when organisms are detected. o Most cases of community acquired pneumonia do not warrant etiological diagnosis due to cost and non-availability of easy bedside rapid tests. o Sputum evaluation is difficult in children as there is low sensitivity and contamination with upper respiratory bacteria, which may or may not be the cause of pneumonia. o Nasopharyngeal swabs are useful if mycoplasma pneumonia, chlamydia, or respiratory viruses are suspected pathogens. o In complicated and severe pneumonia necessitating admission, etiological diagnosis should be attempted. o Extended Pneumonia PCR panels may be helpful. o Blood cultures are positive in less than a quarter of the cases. o Urinary antigen test are generally not useful in children and should not be routinely advised. o Paired blood samples around 10 to 14 days apart may be useful in complement fixation tests for the diagnosis of mycoplasma and chlamydia. TIP 15 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) o In Pneumonias that are unresponsive to treatment, recurrent or rapidly progressive, an attempt must be made to get a microbiological diagnosis. o It is also extremely useful in patients with suspected immunodeficiency. o Getting samples from a relatively uncontaminated area is very useful. We can achieve this either with a BAL sample or a pleural tap. o A bronchio-alveolar lavage sample can be obtained either through a bronchoscope specifically introduced for collection of samples, or through an endotracheal tube which has already been placed for ventilation. The adequately procured BAL sample should then be subjected to simple staining, culture, and PCR based diagnosis. o An extended PCR pneumonia panel is available for not only detecting the probable organism, but also for detecting the presence of microbial resistance genes. TIP 16 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) o Most children with community acquired pneumonia will respond to Amoxicillin given orally. o In some situations, the child may either not respond or worsen as the days go by. o Some clinical pointers are: 1. Infants generally take a longer time to respond to therapy. 2. Viral lower respiratory tract infections will also tend to take a longer time to recover. 3. Pneumonias not responding to beta-lactams, and with predominant cough and non-pulmonary manifestations must raise the suspicion of atypical organisms like mycoplasma and chlamydia. Addition of macrolides or doxycycline may be considered in such situations. 4. Complicated pneumonia is associated with a worsening clinical state. In such situations, ruling out an empyema or necrosis through imaging may be appropriate. 5. Persistence of fever may not be related to the pneumonia itself. Thrombophlebitis or drug induced fever are other causes to look out for. 6. Radiological clearance often takes a few weeks and repeated X rays should not be done TIP 17 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) o Pleural pathology in pneumonia is very common. Around 10% of children with community acquired pneumonia may show evidence of pleural involvement. o The usual etiology of pneumonia is either bacterial or viral. o Among the bacteria, pneumococcal pneumonia is predominant with types 1 and 19 A associated with para pneumonic effusions. o Effusions can also occur with adenoviral and influenza pneumonias. o One should suspect pleural effusion if the child does not respond adequately after starting antibiotics or there are clinical signs suggestive of plural involvement. TIP 18 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) o An X-ray (AP or lateral decubitus view) and ultrasound of the chest will confirm the presence of pleural effusion. o Ultrasound of the chest is very helpful in determining the characteristics of the fluid in the chest. One can determine whether the primary pathology is in the pleura or the lung. o We can also evaluate the volume of pleural fluid which will guide management. o It also gives an idea of whether the effusion is simple or complicated. It helps in drainage of the fluid. o Advantages of an ultrasound are that it is easily available, portable and there is no radiation exposure. o CT scans should be used very sparingly in complicated cases, especially when necrosis of the lung is suspected. TIP 19 (Contributors: Dr.Jagdish Chinappa & Dr.Vijay Yewale) o Management of pleural fluid should be guided by three factors: 1. The clinical progress of the patient 2. Ultrasound findings of simple versus complicated pneumonia, and 3. The volume of fluid in the chest o When the volume is small, i.e less than 25% of the hemithorax continuing with antibiotic is sufficient. o When the volume is around less than 50% of the hemithorax , a pleural tap and drainage may be considered. o If the volume of fluid is more than 50% and if the fluid is loculated, one might consider chest tube, fibrinolytic or VATS. o Evaluation of the pleural fluid helps in distinguishing exudate vs transudate and in identifying the etiology. TIP 20 (Contributors: Dr Jagdish Chinappa & Dr Vijay Yewale) Investigations in infectious disease probably fit into one of the four groups: 1. Triage: When there is a clinical situation where rapid decisions have to be made, the laboratory is invaluable in making this decision. With the availability of rapid point of care tests, this can be very useful in conditions like Covid, Influenza and RSV. 2. As an aid to confirm or refute a clinical diagnosis: For example when where is whitish membrane on the tonsil a rapid strep test or blood culture in the case of PUO. 3. To Guide appropriate antibiotic therapy: To avoid antibiotic therapy if a viral infection is most likely, to give the most appropriate antibiotic based on sensitivity patterns eg in Typhoid or MRSA & to escalate or de- escalate antibiotics. 4. To Evaluate unusual course (poor response) or complications: eg Iris syndrome in TB, Non response in a complicated UTI. TIP 21A(Contributors:Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jeetendra Gavhane) Dengue is endemic with seasonal increase. The Dengue season starts with monsoon and extends 4-5 months later. o o 1. 2. Dengue is best treated by suspecting it in every child with AFI. Following a Dengue infested mosquito bite the outcome may be: Asymptomatic infection Primary Dengue (1st encounter): It's a mild URI like illness especially in infants and young children. This is usually not tested and diagnosed or labelled as primary dengue. In older children - fever from 2 to 7 days, flushing, loss of appetite, backache, retro orbital pain, and rash are the presenting symptoms with palpable liver, spleen & lymphadenopathy. Child may have purpura. Adolescent girl may have increased flow if in menses. A normal to low WBC with or without low platelets is seen. HCT is usually normal. 3. Secondary Dengue: It is a second encounter in a child who has had a past infection (which is often undiagnosed and has gone unnoticed). Hence in every dengue at diagnosis, presume secondary dengue. Fever lasts for 3-4 days, then the child becomes afebrile, however, he is unwell due to low tissue perfusion as he starts leaking .This is evident by rising Hb/HCT and platelet drop. Less urine, dark urine, rash, purpura, epigastric abdominal pain, & vomiting are symptoms suggesting onset of leaky phase. Any physical activity is like exertion. o What we must watch out for on day 3 or 4 of fever: Look at urine output, tachycardia clinically and Hb/HCT on serial CBC. o The leak usually lasts for 48 hrs. The degree of leak varies. Monitor HR, intake (oral and IV), and output meticulously. TIP 21B(Contributors: Dr Vijay Yewale & Dr Jeetendra Gavhane) Management of Dengue o Aim at maintaining urine output of 0.5 - 1ml per kg per hr and adjust intake accordingly. o The more you infuse, the more the child will leak in the extravascular compartment. So target intake( oral and IV) just enough to maintain adequate tissue perfusion as monitored by urine output of 0.5- 1ml/kg/ hr. This is the crux. o By and large, the fluid required from the beginning of the leaky phase (the child becoming afebrile and platelets around 1 lac) to the end of the leaky phase i.e approx. 48 hrs, is not more than 24 hrs maintenance fluid plus 50ml x body weight. o As stated before, the degree of leak varies from child to child and it’s not that all the calculated fluid must be given to every child. Example of a 20 kg child 1. Maintainence fluid 24 hrs = 1500 ml 2. 50ml x body wt (20) = 1000 ml So this child mostly will need fluids not exceeding 2500ml in the 48 hrs of the leaky phase. o So we can start with a maintenance fluid of 2-3 ml/kg/hr, monitor urine output and up regulate depending on the urine output. o Go up to 7ml/kg/hr. Most don't need such a high rate. But if the HCT doesn't fall and urine output is below 0.5ml/kg/hr, we may have to give a colloid. o Once the child maintains urine output and HCT is falling, bring down the fluid rate rapidly and stop it. Remember to take into account oral fluids as well. o A child who not vomiting and is able to take orally, can be managed with oral fluids like ORS. o So for every AFI we see in the OPD, ask the parents to monitor the temperature. When the fever breaks, ask them to watch for less urine, dark urine, rash, listlessness, abdominal pain, and vomiting. o Remember that in the example above, we discussed a typical case tracked from day 0 of illness. But in practice, the child may present during the leaky phase, in compensated or hypotensive shock, or sometimes with fluid overload due to overzealous fluid therapy. So as long as we understand the pathophysiology and the leakage phenomenon, rational management can be done. o A child in shock usually is almost post 24 hrs of leak, so one needs to tide over the next 24 to 48hrs. Give 10 ml per kg over an hr, another dose of 10 ml per kg over an hr and if the HCT doesn't decrease or the child doesn't pass urine, use a colloid 10ml per kg. o Dextran40 is a good colloid, giving a steady oncotic pressure to retain fluids in the vascular compartment. Intensivists with monitoring facilities use albumin. o In a child continuing to have fever beyond 6 days, deranged liver enzymes and rising ferritin, a high index of suspicion for HLH should be kept in mind. o In the discussion above, not once have we talked about absolute platelet count, don't chase it, and it’s almost never to be used. o Inj Vit K is not to be given. Coagulopathy reverses with recovery and adequate fluid management. o Return of appetite and itching indicate recovery. Don't worry about the bradycardia, which is common at recovery. o Let's aim for near zero CFR in Dengue. _________________________ x ________________________